Managerial Accounting

Diunggah oleh

nerurkar_tusharJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Managerial Accounting

Diunggah oleh

nerurkar_tusharHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

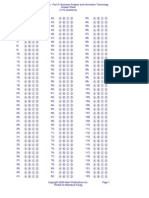

STUDY UNIT SIX

MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING

6.1 Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

6.2 Variable and Absorption Costing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

6.3 Overhead Allocation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

6.4 Process Costing and Job-Order Costing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

6.5 Activity-Based Costing (ABC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

6.6 Service Cost Allocation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

6.7 Joint Products and By-Products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

6.8 Standard Costing and Variance Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

6.9 Types of Budgets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

6.10 Capital Budgeting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

6.11 Relevant Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

6.12 Transfer Pricing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

6.13 Responsibility Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

6.14 Study Unit 6 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Study Unit 6 covers basic concepts of managerial accounting. One basic concept is cost behavior,

that is, whether costs are fixed, variable, or some combination. Cost behavior must be understood to

plan for firm profitability. This study unit also addresses cost allocation methods. These methods are

used to assign indirect costs to cost objects. Other subunits apply to costing systems, budgeting,

certain analytical methods, transfer pricing, and responsibility systems.

Core Concepts

I The breakeven point is the sales level at which total revenues equal total costs.

I Variable and absorption costing result in different inventory measures and profits. Variable (direct)

costing assigns variable but not fixed factory overhead to products. The two methods treat all

other costs in the same way.

I Factory overhead consists of variable and fixed indirect costs that are allocated to units.

I Process cost accounting assigns costs to products or services. It applies to relatively

homogeneous items that are mass produced on a continuous basis (e.g., refined oil). It

calculates an average cost for all units and accumulates costs by cost centers, not jobs.

Moreover, work-in-process is stated in terms of equivalent units of production (EUP). The

objective is to allocate direct materials costs and conversion costs to finished goods, EWIP, and,

possibly, spoilage based on relative EUP. Allocation is based either on the FIFO or the weighted-

average assumption.

I Job-order costing accumulates costs by specific job. Job-order costing is appropriate when

products or services have individual characteristics or when identifiable groupings are possible.

I Cost objects are the intermediate and final dispositions of cost pools. A cost pool is an account in

which a variety of similar costs associated with an activity are accumulated prior to allocation to

cost objects.

I Under activity-based costing (ABC), an entity identifies as many direct costs as feasible.

Furthermore, compared with traditional costing, many more separate pools are established for

costs not directly attributable to cost objects. In ABC, the initial cost objects are activities.

I Cost allocation criteria are (1) cause and effect, (2) benefits received, (3) fairness, and (4) ability to

bear.

I The methods of service cost allocation are the direct method, the step method, and the reciprocal

method.

I Joint costs are normally allocated to joint products but not by-products.

1

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

I The relative sales value method allocates joint costs based on each products proportion of total

sales revenue.

I Standard costs are budgeted unit costs established to motivate optimal productivity and efficiency.

When actual costs and standard costs differ, the difference is a variance.

I Direct materials variances are usually divided into price and efficiency components. Part of a total

materials variance may be attributed to using more raw materials than the standard and part to a

cost that was higher than standard. Direct labor variances are similar to direct materials

variances.

I In a four-way analysis of factory overhead variances, the variable components are the spending

and efficiency variances. The fixed components are the budget and volume variances.

I The sales variances are the sales price variance and the sales volume variance (sum of the sales

mix and quantity variances).

I A budget (profit plan) is a realistic plan for the future expressed in quantitative terms.

I The operating budget sequence is the part of the master budget process that begins with the sales

budget and ends with the pro forma income statement.

I The financial budget sequence is the part of the master budget process that incorporates the cash

budget, capital budget, and pro forma financial statements.

I Capital budgeting is the process of planning expenditures for assets, the returns on which are

expected to continue beyond 1 year. Capital budgeting requires choosing among investment

proposals. The basic ranking methods are payback, net present value, and internal rate of return.

I Relevant costs are those expected future costs that vary with the action taken. All other costs are

assumed to be constant and thus have no effect on (are irrelevant to) the decision.

I Transfer prices are the amounts charged by one segment of an organization for goods and

services it provides to another segment of the same organization. A transfer price should permit

a segment to operate independently and meet its goals while serving the best interests of the

firm. Hence, transfer pricing should motivate managers. It should encourage goal congruence

and managerial effort.

I A responsibility system should encourage the efficient achievement of organizational goals. Thus,

managerial control should promote goal congruence and managerial effort.

I A responsibility center is an organizational subunit, such as a department, plant, division, or

segment, whose manager has authority over and is responsible and accountable for a defined

group of activities.

6.1 COST-VOLUME-PROFIT (CVP) ANALYSIS

1. CVP (breakeven) analysis predicts the relationships among revenues, variable costs, and

fixed costs at various production levels. It determines the probable effects of changes in

sales volume, sales price, product mix, etc.

2. The variables include

a. Revenue as a function of price per unit and quantity produced

b. Fixed costs

c. Variable cost per unit or as a percentage of sales

d. Profit per unit or as a percentage of sales

3. The inherent simplifying assumptions used in CVP analysis are the following:

a. Costs and revenues are predictable and are linear over the relevant range.

b. Total variable costs change proportionally with volume, but unit variable costs are

constant over the relevant range.

c. Changes in inventory are insignificant in amount.

d. Total fixed costs remain constant over the relevant range of volume, but unit fixed

costs vary indirectly with volume.

e. Selling prices remain fixed.

2 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

f. Production equals sales.

g. The product mix is constant, or the firm makes only one product.

h. A relevant range exists in which the various relationships are true for a given time

span.

i. All costs are either fixed or variable relative to a given cost object.

j. Productive efficiency is constant.

k. Costs vary only with changes in physical sales volume.

l. The breakeven point is directly related to costs and indirectly related to the budgeted

margin of safety and the contribution margin.

4. Definitions

a. The relevant range is the set of limits within which the cost and revenue relationships

remain linear and fixed costs are fixed.

b. The breakeven point is the sales level at which total revenues equal total costs.

c. The margin of safety is the excess of budgeted sales dollars over breakeven sales

dollars (or budgeted units over breakeven units).

d. The sales mix is the composition of total sales in terms of various products, i.e., the

percentages of each product included in total sales. It is maintained for all volume

changes.

e. The unit contribution margin (UCM) is the unit selling price minus the unit variable

cost. It is the contribution from the sale of one unit to cover fixed costs (and possibly

a targeted profit).

1) It is expressed as either a percentage of the selling price (contribution margin

ratio) or a dollar amount.

2) The UCM is the slope of the total cost line plotted so that volume is on the x axis

and dollar value is on the y axis.

5. Breakeven Formula

a. P = S FC VC If: P = profit (zero at breakeven)

S = XY S = sales

FC = fixed costs

VC = variable costs

X = quantity of units sold

Y = unit sales price

6. Applications

a. The basic problem equates sales with the sum of fixed and variable costs.

1) EXAMPLE: Given a selling price of $2.00 per unit and variable costs of 40%,

what is the breakeven point if fixed costs are $6,000?

S = FC + VC

2.00X = $6,000 + $.80X

1.20X = $6,000

X = 5,000 units at breakeven point

2) The same result can be obtained by dividing fixed costs by the UCM.

3) The breakeven point in dollars can be calculated by dividing fixed costs by the

contribution margin ratio.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 3

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

b. An amount of profit, either in dollars or as a percentage of sales, may be required.

1) EXAMPLE: If units are sold at $6.00 and variable costs are $2.00, how many

units must be sold to realize a profit of 15% ($6.00 .15 = $.90 per unit) before

taxes, given fixed costs of $37,500?

S = FC + VC + P

6.00X = $37,500 + $2.00X + $.90X

3.10X = $37,500

X = 12,097 units at breakeven to earn a 15% profit

2) The desired profit of $.90 per unit is treated as a variable cost. If the desired

profit were stated in total dollars rather than as a percentage, it would be

treated as a fixed cost.

3) Selling 12,097 units results in $72,582 of sales. Variable costs are $24,194 and

profit is $10,888 ($72,582 15%). The proof is that fixed costs of $37,500, plus

variable costs of $24,194, plus profit of $10,888 equals $72,582 of sales.

c. Sales mix. Multiple products may be involved in calculating a breakeven point.

1) EXAMPLE: If A and B account for 60% and 40% of total sales, respectively, and

the variable cost ratios are 60% and 85%, respectively, what is the breakeven

point, given fixed costs of $150,000?

S = FC + VC

S = $150,000 + .6(.6S) + .85(.4S)

S = $150,000 + .36S + .34S

.30S = $150,000

S = $500,000

a) In effect, the result is obtained by calculating a weighted-average

contribution margin ratio (30%) and dividing it into the fixed costs to arrive

at the breakeven point in sales dollars.

b) Another approach is to divide fixed costs by the UCM for a composite unit

(when unit prices are known) to determine the number of composite

units. The number of individual units can then be calculated.

d. Sometimes breakeven analysis is applied to analysis of the profitability of special

orders. This application is essentially contribution margin analysis.

1) EXAMPLE: What is the effect of accepting a special order for 10,000 units at

$8.00, given the following unit operating data?

Per Unit

Sales $12.50

Manufacturing costs -- variable (6.25)

-- fixed (1.75)

Gross profit $ 4.50

Selling expenses -- variable (1.80)

-- fixed (1.45)

Operating profit $ 1.25

a) The assumptions are that (1) idle capacity is sufficient to manufacture

10,000 extra units, (2) sale at $8.00 per unit will not affect the price or

quantity of other units sold, and (3) no additional selling expenses are

incurred.

b) Because the variable cost of manufacturing is $6.25, the UCM is $1.75

($8 special-order price $6.25). The increase in operating profit is

$17,500 ($1.75 10,000 units).

4 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

6.2 VARIABLE AND ABSORPTION COSTING

1. Variable and absorption costing result in different inventory and profit measures. They also

result in income statements in which the classification and order of costs are different.

Under absorption (full) costing, all factory (manufacturing) overhead costs are product

costs. They are not expensed until the product is sold.

2. Variable (direct) costing assigns variable but not fixed factory overhead to products.

a. The term direct costing may be misleading because it suggests traceability, which is

not what cost accountants mean when they speak of direct costing. Many

accountants believe that variable costing is a more suitable term, and some even

call the method contribution margin reporting.

3. Variable and absorption costing are just two of a continuum of possible inventory costing

methods. At one extreme is supervariable costing, which treats direct materials as the

only variable cost. At the other extreme is superabsorption costing, which treats costs

from all links in the value chain as inventoriable.

4. Under variable costing, all direct labor, direct materials, variable factory overhead costs, and

selling and administrative costs are accounted for in the same way as under absorption

costing. Only fixed factory overhead costs are treated differently. They are period

costs. Thus, they are expensed when incurred.

a. EXAMPLE: A firm, during its first month in business, produced 100 units of product X

and sold 80 units while incurring the following costs:

Direct materials $100

Direct labor 200

Variable factory overhead 150

Fixed factory overhead 300

1) Given total costs of $750, the absorption cost per unit is $7.50 ($750

100 units). Thus, total ending inventory is $150 (20 $7.50). Using variable

costing, the cost per unit is $4.50 ($450 100 units), and the total value of the

remaining 20 units is $90.

2) If the unit sales price is $10, and the company incurred $20 of variable selling

expenses and $60 of fixed selling expenses, the following income statements

result from using the two methods:

Variable Cost Absorption Cost

Sales $800

Beginning inventory $ 0

Variable cost of

manufacturing 450

$450

Ending inventory (90)

Variable cost of goods cost (360)

Manufacturing contribution

margin $440

Variable selling expenses (20)

Contribution margin $420

Fixed factory overhead (300)

Fixed selling expenses (60)

Operating profit $ 60

Sales $800

Beginning inventory $ 0

Cost of goods

manufactured 750

Cost of goods available

for sale $750

Ending inventory (150)

Cost of goods sold (600)

Gross margin $200

Selling expenses (80)

Operating profit $120

3) The $60 difference in operating profit ($120 $60) is the difference between the

two ending inventory values ($150 $90). In essence, the absorption method

treats 20% of the fixed factory overhead costs ($300 20% = $60) as an asset

(inventory) because 20% of the months production (100 80 sold = 20) is still

on hand. The variable-costing method assumes that the fixed factory overhead

costs are not product costs because they would have been incurred even if no

production had occurred.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 5

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

4) The contribution margin is an important element in the variable costing income

statement. It equals sales minus total variable costs. It indicates how much

sales contribute toward covering fixed costs and providing a profit.

5. Variable costing permits the adoption of the contribution approach to performance

measurement. This approach is emphasized because it focuses on controllability. Fixed

costs are much less controllable than variable costs. Thus, the contribution margin

(revenues all variable costs) may be a fairer basis for evaluation than gross margin (also

called gross profit), which equals revenues minus cost of sales.

a. Allocation of central administration costs (allocated common costs) is a fundamental

issue in responsibility accounting. It has often been made based on budgeted

revenue or contribution margin. If allocation is based on actual sales or contribution

margin, a responsibility center that surpasses expectations will be penalized (charged

with increased overhead).

1) Research has shown that central administrative costs are allocated to

organizational subunits for the following reasons:

a) The allocation reminds managers that such costs exist and that the

managers would incur these costs if their operations were independent.

b) The allocation also reminds managers that profit center earnings must

cover some amount of support costs.

c) Organizational subunits should be motivated to use central administrative

services appropriately.

d) Managers who must bear the costs of central administrative services that

they do not control may exert pressure on those who do.

2) If central administrative or other fixed costs are not allocated, responsibility

centers might reach their revenue or contribution margin goals without covering

all fixed costs, a necessity to operate in the long run.

3) Allocation of overhead, however, is motivationally negative. Central

administrative or other fixed costs may appear noncontrollable and be

unproductive. Furthermore,

a) Managers morale may suffer when allocations depress operating results.

b) Dysfunctional conflict may arise among managers when costs controlled

by one are allocated to others.

c) Resentment may result if cost allocation is perceived to be arbitrary or

unfair. For example, an allocation on an ability-to-bear basis, such as

operating profit, penalizes successful managers and rewards

underachievers and may therefore have a demotivating effect.

4) A much preferred alternative is to budget a certain amount of the contribution

margin earned by each responsibility center to the central administration based

on negotiation. The hoped-for result is for each subunit to see itself as

contributing to the success of the overall entity rather than carrying the weight

(cost) of central administration.

a) The central administration can then make the decision whether to expand,

divest, or close responsibility centers.

6 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

6.3 OVERHEAD ALLOCATION

1. Factory overhead consists of indirect manufacturing costs that cannot be assigned to

specific units of production. They are allocated to units (most often using an annual rate)

because they are incurred as a necessary part of the production process. Allocation

bases (activity levels) in traditional cost accounting include direct labor hours, direct labor

cost, machine hours, materials cost, and units of production. An allocation base should

have a high correlation with the incurrence of overhead.

2. The distinction between variable and fixed factory overhead rates should be understood.

Variable factory overhead per unit of the allocation base is assumed to be constant within

the relevant range of activity. Thus, estimation of the variable factory overhead rate

emphasizes the per-unit amount. However, fixed factory overhead is assumed to be

constant in total over the relevant range. Accordingly, the fixed factory overhead rate

equals the total budgeted cost divided by the appropriate denominator (capacity) level.

a. The use of an annual predetermined fixed factory overhead application rate is

often preferred. It smoothes cost fluctuations that would otherwise occur as a result

of fluctuations in production from month to month. Thus, higher overhead costs are

not assigned to units produced in low production periods and vice versa. The

denominator of the fixed factory overhead rate may be defined in terms of various

capacity concepts.

1) Theoretical or ideal capacity is the level at which output is maximized

assuming perfectly efficient operations at all times. This level is impossible to

maintain and results in underapplied overhead.

2) Practical capacity is theoretical capacity minus idle time resulting from holidays,

downtime, changeover time, etc., but not from inadequate sales demand.

3) Normal capacity is the level of activity that will approximate demand over a

period of years. It includes seasonal, cyclical, and trend variations. Deviations

in one year will be offset in other years.

4) Expected actual activity is a short-run activity level. It minimizes under- or

overapplied overhead but does not provide a consistent basis for assigning

overhead cost. Per-unit overhead will fluctuate because of short-term changes

in the expected production level.

3. Overapplied overhead (a credit balance in factory overhead) results when product costs

are overstated because the activity level was higher than expected or actual overhead

costs were lower than expected.

a. Underapplied overhead (a debit balance in factory overhead) results when product

costs are understated because the activity level was lower than expected or actual

overhead costs were higher than expected.

b. Unit variable factory overhead costs and total fixed factory overhead costs are

expected to be constant within the relevant range. Accordingly, when actual

activity is significantly greater or less than planned, the difference between the actual

and predetermined fixed factory overhead rates is likely to be substantial. However,

a change in activity, by itself, does not affect the variable rate.

c. The treatment of over- or underapplied overhead depends on the materiality of the

amount. If the amount is immaterial, it may be debited or credited to cost of goods

sold.

1) If the amount is material, it should theoretically be allocated to work-in-

process, finished goods, and cost of goods sold on the basis of the

currently applied overhead in each of the accounts. This procedure will restate

inventory costs and cost of goods sold to the amounts actually incurred. An

alternative is to prorate the variance based on the total balances in the

accounts.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 7

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

4. Two factory overhead accounts may be used: factory overhead control and factory

overhead applied.

a. As actual overhead costs are incurred, they are debited to the control account. As

overhead is applied (transferred to work-in-process) based on a predetermined rate,

the factory overhead applied account is credited.

b. Assuming proration of under- or overapplied overhead, the entry to close the

overhead accounts is

Cost of goods sold (Dr or Cr) $XXX

Work-in-process (Dr or Cr) XXX

Finished goods (Dr or Cr) XXX

Factory overhead applied XXX

Factory overhead control $XXX

5. The improvements in information technology and decreases in its cost have made a

restated allocation rate method more appealing. This approach is implemented at the

end of the period to calculate the actual overhead rates and then restate every entry

involving overhead. The effect is that job-cost records, the inventory accounts, and cost of

goods sold are accurately stated with respect to actual overhead. This means of disposing

of variances is costly but improves the analysis of product profitability.

6. The foregoing discussion assumes that normal costing methods are applied. Under

normal costing, amounts are recorded for direct costs at actual rates and prices times

actual inputs. For indirect costs, budgeted rates are used.

a. Under actual costing, however, actual rates are used to record indirect costs.

b. Under budgeted costing, budgeted rates and prices are used for direct costs, and

budgeted rates are used for indirect costs.

c. In practice, organizations may combine these methods in various ways.

7. The outline also emphasizes cost control systems for manufacturing entities. However,

the basic concepts also are applicable to service and retailing organizations, although

without the complications resulting from the need to account for inventories in process. For

example, job-order costing principles apply to an audit by an accounting firm, and the costs

of routine mail delivery may be controlled using process costing techniques.

6.4 PROCESS COSTING AND JOB-ORDER COSTING

1. Process cost accounting assigns costs to products or services. It applies to relatively

homogeneous items that are mass produced on a continuous basis (e.g., refined oil).

a. The objective is to determine the portion of cost that is to be expensed because the

products or services were sold and the portion that is to be deferred.

b. Process costing is an averaging process that calculates the average cost of all units.

Thus, the costs are accumulated by cost centers, not jobs. Moreover, in a

manufacturing setting, work-in-process (WIP) inventory is stated in terms of

equivalent units of production (EUP) so that average costs may be calculated.

8 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

c. A manufacturing entitys direct materials, direct labor, and factory overhead are

debited to WIP when they are committed to the process.

1) The sum of these costs and the beginning WIP (BWIP) is the total production

cost to be accounted for in any one period. This total is allocated to finished

goods and to ending WIP (EWIP), which may be credited for abnormal

spoilage.

2) Direct materials are usually accounted for in a separate account.

Direct materials inventory $XXX

Accounts payable or cash $XXX

3) When direct materials are transferred to WIP, inventory is credited.

4) Direct labor is usually debited directly to WIP when the payroll is recorded. Any

wages not attributable directly to production, e.g., those for janitorial services,

are considered indirect labor and debited to overhead. Shift differentials and

overtime premium are likewise deemed to be overhead. However, these

amounts are charged to a specific job when a customer requirement, rather

than a management decision, causes the differential in the overtime.

WIP $XXX

Factory overhead XXX

Wages payable $XXX

Payroll taxes payable XXX

5) Indirect costs were traditionally debited to a single factory overhead control

account. However, under activity-based costing (ABC), many such accounts

are used.

a) They include supplies, plant depreciation, etc.

Factory overhead $XXX

Insurance expense $XXX

Supplies expense XXX

Depreciation expense (or accum. dep.) XXX

b) To charge all factory overhead incurred over a period, such as a year, to

WIP, factory overhead is credited and WIP is debited on some systematic

basis.

WIP $XXX

Factory overhead $XXX

6) Transferred-in costs are similar to direct materials added at a point in the

process because both attach to (become part of) the product at that point,

usually the beginning of the process. However, transferred-in costs are

dissimilar because they attach to the units of production that move from one

process to another. Thus, they are the basic units being produced. By

contrast, direct materials are added to the basic units during processing.

7) As goods are completed, their cost is credited to WIP and debited to finished

goods. When the finished goods are sold, their cost is debited to cost of

sales. The deferred manufacturing costs are held in the ending WIP, finished

goods inventory, and direct materials inventory accounts.

Finished goods inventory $XXX

WIP $XXX

Cost of goods sold $XXX

Finished goods inventory $XXX

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 9

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

8) In the following T account illustration, each arrow represents a journal entry to

record a transfer. It indicates a credit to the original account and a debit to the

next account in the sequence.

a) Cost of goods manufactured (CGM) equals the costs of goods

completed in the current period and transferred to finished goods

(BWIP + DM + DL + FOH EWIP).

b) For simplicity, a single overhead account is shown. However, many

accountants prefer to accumulate actual costs (debits) in the overhead

control account and the amounts charged to WIP in a separate

overhead applied account. This account will have a credit balance.

Overhead applied is based on a predetermined rate.

c) The debits to WIP are the total costs incurred. They equal the sum of

the CGM, EWIP, and abnormal spoilage.

d) Abnormal spoilage is not inherent in the particular process. It is charged

to a loss in the period in which detection occurs. However, normal

spoilage is a product cost included in CGM and EWIP.

2. Equivalent units of production (EUP) measure the amount of work performed in each

production phase in terms of fully processed units during a given period. An equivalent unit

is a set of inputs required to manufacture one physical unit. Calculating EUP for each

factor of production facilitates measurement of output and cost allocation when WIP exists.

a. Incomplete units are restated as the equivalent amount of completed units. The

calculation is made separately for direct materials (transferred-in costs are treated

as direct materials for this purpose) and conversion cost (direct labor and factory

overhead).

b. One equivalent unit is the amount of conversion cost (direct labor and factory

overhead) or direct materials cost required to produce one finished unit.

1) EXAMPLE: If 10,000 units in EWIP are 25% complete, they equal 2,500

(10,000 25%) equivalent units.

2) Some units may be more advanced in the production process with respect to

one factor than another; e.g., a unit may be 75% complete as to direct materials

but only 15% complete as to direct labor.

10 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

c. The objective is to allocate direct materials costs and conversion costs to finished

goods, EWIP, and, possibly, spoilage based on relative EUP.

d. Under the FIFO assumption, only the costs incurred this period are allocated between

finished goods and EWIP. Beginning inventory costs are maintained separately from

current-period costs. Thus, goods finished this period are costed separately as either

started last period or started this period.

1) The FIFO method determines equivalent units by subtracting the work done on

the BWIP in the prior period from the weighted-average total.

e. The weighted-average assumption averages all direct materials and all conversion

costs (both those incurred this period and those in BWIP). No distinction is made

between goods started in the preceding and the current periods.

1) The weighted-average EUP calculation differs from the FIFO calculation by the

amount of EUP in BWIP. EUP equal the EUP transferred to finished goods

plus the EUP in EWIP. Total EUP completed in BWIP are not deducted.

f. Example of the Weighted-Average Assumption

1) Roy Company manufactures Product X in a two-stage production cycle in

Departments A and B. Direct materials are added at the beginning of the

process in Department B. Roy uses the weighted-average method. BWIP

(6,000 units) for Department B was 50% complete as to conversion costs.

EWIP (8,000 units) was 75% complete. During February, 12,000 units were

completed and transferred out of Department B. An analysis of the costs

relating to WIP and production activity in Department B for February follows:

Transferred- Materials Conversion

in Costs Costs Costs

BWIP $12,000 $2,500 $1,000

Costs added 29,000 5,500 5,000

The total cost per equivalent unit transferred out is equal to the unit cost for

transferred-in costs, materials costs, and conversion costs. Transferred-in

costs are by definition 100% complete. Given that materials are added at the

beginning of the process in Department B, all units are complete as to

materials. Conversion costs are assumed to be uniformly incurred. Units in the

table are shown in thousands.

Units % T-I % DM % CC

Completed 12 100 12 100 12 100 12

EWIP 8 100 8 100 8 75 6

Equivalent units 20 20 18

Transferred in:

($12,000 + $29,000 )

20,000 EUP

= $2.05

Materials cost:

($2,500 + $5,500 )

20,000 EUP

= .40

Conversion cost:

($1,000 + $5,000 )

18,000 EUP

= .33

Total Unit Cost = $2.78

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 11

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

g. Example of the FIFO assumption

1) The Cutting Department is the first stage of Mark Companys production cycle.

BWIP for this department was 80% complete as to conversion costs, and EWIP

was 50% complete. Information as to conversion costs in the Cutting

Department for January is given below.

Units CC

WIP at January 1 25,000 $ 22,000

Units started and costs incurred

during January 135,000 143,000

Units completed and transferred to

next department during January 100,000

When using the FIFO method of process costing, EUP for a period include only

the work done that period and exclude any work done in a prior period. The

total of conversion cost EUP for the period is calculated below.

Work Done

in Current

Units Period CC (EUP)

BWIP 25,000 20% 5,000

Started & completed 75,000 100% 75,000

EWIP 60,000 50% 30,000

Total EUP 110,000

The total of the conversion costs for the period is given as $143,000. Dividing

by total EUP of 110,000 gives a unit cost of $1.30. The conversion cost of the

EWIP inventory is equal to the EUP in EWIP (30,000) times the unit cost

($1.30) for the current period, or $39,000.

3. Job-order costing accumulates costs by specific job. This method is at the opposite end of

the continuum from process costing. In practice, organizations tend to combine elements

of both approaches. Job-order costing is appropriate when products or services have

individual characteristics or when identifiable groupings are possible. For example, the

entity may produce batches of certain styles or types of furniture.

a. Units (jobs) should be dissimilar enough to warrant the special record keeping

required by job-order costing. Costs are recorded by classification (direct materials,

direct labor, and factory overhead) on a job-cost sheet specifically prepared for each

job.

b. The difference between process and job-order costing is often overemphasized.

Job-order costing simply requires subsidiary ledgers to record the additional details

needed to account for specific jobs. However, the totals of subsidiary ledger amounts

should equal the balances of the related general ledger control accounts. These

are the basic accounts used in process costing. For example, the total of all amounts

recorded on job-cost sheets for manufacturing jobs in process equals the balance in

the WIP control account.

c. Source documents for costs incurred include stores requisitions for direct materials

and work (or time) tickets for direct labor.

d. Overhead is usually assigned to each job through a predetermined overhead rate,

e.g., $3 of overhead for every direct labor hour.

1) Items that are attributable to all jobs, for example, an overtime premium or scrap

that is an inevitable part of production, is allocated through the overhead

account.

e. Journal entries record direct materials, direct labor, and factory overhead used for a

specific job. They are similar to the entries used in process costing.

12 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

f. Evaluating the efficiency of production under a job-order system can be done by use

of a standard cost system. Costs for each job also may be budgeted individually,

based on expected materials and labor usage.

g. A summary of the accounting process for a manufacturers job-order system

follows:

COST ELEMENT

SOURCE OF DATA

DRECT MATERALS

MATERALS

REQUSTONS

DRECT LABOR

FACTORY OVERHEAD

TME TCKETS

Predetermined

rate based on

estimated costs

JOB-COST SHEET

(Stored in WP file)

JOB-COST SHEET

(Stored in FG File)

JOB-COST SHEET

(Stored in CGS File)

Work is complete

Goods are sold

4. Operation costing is a hybrid of job-order and process costing systems used by companies

that manufacture batches of similar units that are subject to selected processing steps

(operations). Different batches may pass through different sets of operations, but all units

are processed identically within a given operation.

a. Operation costing may also be appropriate when different materials are processed

through the same basic operations, such as the woodworking, finishing, and polishing

of different product lines of furniture.

b. Operation costing accumulates total conversion costs and determines a unit

conversion cost for each operation. This procedure is similar to overhead allocation.

However, direct materials costs are charged specifically to products as in job-order

systems.

c. More work-in-process accounts are needed. One is required for each operation.

6.5 ACTIVITY-BASED COSTING (ABC)

1. Key Terms

a. Cost objects are the intermediate and final dispositions of cost pools. Intermediate

cost objects receive temporary accumulations of costs as the cost pools move from

their originating points to the final cost objects. A final cost object, such as a job,

product, or process, should be logically linked with the cost pool based on a cause-

and-effect relationship.

b. A cost pool is an account in which a variety of similar costs associated with an activity

are accumulated prior to allocation to cost objects. The overhead account is a cost

pool into which various types of overhead are accumulated prior to their allocation.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 13

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

2. Activity-based costing (ABC) may be used by manufacturing, service, or retailing entities

and in job-order or process costing systems. It has been popularized because of the rapid

advance of technology, which has led to a significant increase in the incurrence of indirect

costs and a consequent need for more accurate cost assignment. However,

developments in computer and related technology (such as bar coding) also allow

management to obtain better and more timely information at relatively low cost.

a. Miscosting of one product causes the miscosting of other products. In traditional

systems, (a) direct labor and direct materials are traced to products or service units,

(b) a single pool of costs (overhead) is accumulated for a given organizational unit,

and (c) these costs are then assigned using an allocative rather than a tracing

procedure. The effect is an averaging of costs that may result in significant

inaccuracy when products or service units do not use similar amounts of resources.

3. Under ABC, an organization identifies as many direct costs as economically feasible. It

also increases the number of separate pools for costs not directly attributable to cost

objects.

a. Each pool should be homogeneous. It should consist of costs that have substantially

similar relationships with the driver or other base used for assignment to cost

objects. The appropriate base preferably is one with a driver or cause-and-effect

relationship (a high correlation) between the demands of the cost object and the

costs in the pool.

4. ABC improves costing by assigning costs to activities rather than to an organizational

unit. Accordingly, ABC requires identification of the activities that consume resources and

that are subject to demands by ultimate cost objects.

a. Design of an ABC system starts with process value analysis, a comprehensive

understanding of how an organization generates its output. It involves a

determination of which activities that use resources are nonvalue-adding and how

they may be reduced or eliminated.

1) This linkage of product costing and continuous improvement of processes is

activity-based management (ABM). It encompasses driver analysis, activity

analysis, and performance measurement.

5. Once an ABC system has been designed, costs may be assigned to the identified

activities. Moreover, costs of related activities that can be reassigned using the same

driver or other base are combined in homogeneous cost pools, and an overhead rate is

calculated for each pool.

a. The next step is to assign costs to ultimate cost objects. In other words, cost

assignment is a two-stage process. First, costs are accumulated for an activity.

This assignment is based on the resources the activity can be directly observed to

use and on the resources it can be assumed to use based on its consumption of

resource drivers. These are factors that cause changes in the costs of an activity.

Second, costs are reassigned to ultimate cost objects on the basis of activity

drivers. These are factors measuring the demands made on activities.

1) Ultimate cost objects may include not only products and services but also

customers, distribution channels, or other objects for which activity and

resource costs may be accumulated.

14 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

6. An essential element of ABC is driver analysis. It emphasizes the search for (a) the

cause-and-effect relationship between an activity and its consumption of resources and

(b) an activity and the demands made on it by a cost object. For this purpose, activities

and their drivers have been classified in accounting literature as follows:

a. Unit-level (volume-related) activities occur when a unit is produced, e.g., direct labor

and direct materials activities.

b. Batch-level activities occur when a batch of units is produced, e.g., ordering, setup, or

materials handling.

c. Product- or service-level (product- or service-sustaining) activities provide support of

different kinds to different types of output, e.g., engineering changes, inventory

management, or testing.

d. Facility-level (facility-sustaining) activities concern overall operations, e.g.,

management of the physical plant, personnel administration, or security

arrangements.

7. Activities are grouped by level, and drivers are determined for the activities. Within each

grouping of activities, the cost pools for activities that can use the same driver are

combined into homogeneous cost pools. In contrast, traditional systems assign costs

largely on the basis of unit-level drivers.

a. At the unit level, examples of drivers are direct labor hours or dollars, machine hours,

and units of output.

b. At the batch level, drivers may include number or duration of setups, orders

processed, number of receipts, weight of materials handled, or number of

inspections.

c. At the product level, drivers may include design time, testing time, number of

engineering change orders, or number of categories of parts.

d. At the facility level, drivers may include any of those used at the first three levels.

8. The first three levels of activities pertain to specific products or services, but facility-level

activities do not. Thus, facility-level costs are not accurately assignable to products. The

theoretically sound solution may be to treat these costs as period costs. Nevertheless,

organizations that apply ABC ordinarily assign them to products to obtain a full absorption

cost suitable for external financial reporting.

9. Organizations most likely to benefit from using ABC are those with (a) products or services

that vary significantly in volume, diversity of activities, and complexity of operations;

(b) relatively high overhead costs; or (c) operations that have undergone major

technological or design changes.

a. However, service organizations may have some difficulty in implementing ABC.

They tend to have relatively high levels of facility-level costs that are difficult to

assign to specific service units. They also engage in many nonuniform human

activities for which information is not readily accumulated. Furthermore, output

measurement is more problematic in service than in manufacturing entities.

Nevertheless, ABC has been adopted by various insurers, banks, railroads, and

health care providers.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 15

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

6.6 SERVICE COST ALLOCATION

1. Service (support) department costs are considered part of overhead (indirect costs).

They cannot feasibly be traced to cost objects. Thus, they must be allocated to the

operating departments that use the services.

a. When service departments also render services to each other, their costs may be

allocated to each other before allocation to operating departments.

2. Allocation Criteria

a. Cause and effect should be used if possible because of its objectivity and acceptance

by operating management.

b. Benefits received is the most frequently used criterion when cause and effect cannot

be determined. However, it requires an assumption about the benefits received. For

example, advertising may promote the company, not specific products. In this case,

an assumption may be made that the advertising resulted in the increased sales

recorded by the various divisions.

c. Fairness is sometimes mentioned in government contracts but appears to be more of

a goal than an objective allocation base.

d. Ability to bear (based on profits) is usually unacceptable because of its dysfunctional

effect on managerial motivation.

3. The direct method is the simplest and most common method. It allocates costs directly to

the producing departments without recognition of services provided among the service

departments.

a. Allocations of service department costs are made only to production departments

based on their relative use of services.

4. The step method includes an allocation of service department costs to other service

departments in addition to the producing departments.

a. The allocation may begin with the costs of the service department that

1) Provides the highest percentage of its total services to other departments,

2) Provides services to the greatest number of other departments, or

3) Has the greatest dollar cost of services provided to other departments.

b. The costs of the remaining service departments are then allocated in the same

manner. No cost is assigned to service departments whose costs have already been

allocated.

c. The process continues until all service department costs are allocated.

5. The reciprocal method is the most theoretically sound. It allows reflection of all reciprocal

services among service departments.

a. The step method considers only services rendered among service departments in one

direction, but the reciprocal method considers services in both directions.

1) If all reciprocal services are recognized, linear algebra may be used to reach a

solution. The typical problem on a professional examination can be solved

using two or three simultaneous equations.

16 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

6.7 JOINT PRODUCTS AND BY-PRODUCTS

1. Definitions

a. Joint products are two or more separate products produced by a common

manufacturing process from a common input. The joint costs of two or more joint

products with significant values are usually allocated to the joint products at the point

at which they became separate products.

b. By-products are one or more products of relatively small total value that are produced

simultaneously from a common manufacturing process with products of greater value

and quantity (joint products).

c. Joint costs (sometimes called common costs) are incurred prior to the split-off

point to produce two or more goods manufactured simultaneously by a single

process or series of processes. Joint costs, which include direct materials, direct

labor, and overhead, are not separately identifiable. They and must be allocated to

the individual joint products.

d. At the split-off point, the joint products acquire separate identities. Costs incurred

after split-off are separable costs.

e. Separable costs can be identified with a particular joint product and allocated to a

specific unit of output. They are the costs incurred for a specific product after the

split-off point.

2. Several methods are used to allocate joint costs. Each assigns a proportionate amount of

the total cost to each product on a quantitative basis.

a. The physical-unit method is based on some physical measure such as volume,

weight, or a linear measure.

b. The sales-value method is based on the relative sales values of the separate

products at split-off.

c. The estimated net realizable value (NRV) method is based on final sales value

minus separable costs.

d. The constant gross margin percentage NRV method is based on allocating joint

costs so that the percentage is the same for every product.

1) This method (a) determines the overall percentage, (b) subtracts the appropriate

gross margin from the final sales value of each product to calculate total costs

for that product, and (c) subtracts the separable costs to arrive at the joint cost

amount.

3. Joint costs are normally allocated to joint products but not by-products. The most

cost-effective method for the initial recognition of by-products is to account for their value

at the time of sale as a reduction in the cost of goods sold or as a revenue. Thus, cost

of sales does not exist for by-products.

a. The alternative is to recognize their value at the time of production, a method that

results in the recording of by-product inventory. Under this method, the value of

the by-product also may be treated as a reduction in cost of goods sold or as a

separate revenue item. The value to be reported for by-products may be sales

revenue, sales revenue minus a normal profit, or estimated net realizable value.

b. By-products usually do not receive an allocation of joint costs because the cost of this

accounting treatment ordinarily exceeds the benefit. However, allocating joint

costs to by-products is acceptable. In that case, they are treated as joint products

despite their small relative values.

c. Scrap is similar to a by-product. Joint costs are almost never allocated to scrap.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 17

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

4. The relative sales value method is the most frequently used way to allocate joint costs to

joint products. It allocates joint costs based upon each products proportion of total sales

revenue.

a. For joint products salable at the split-off point, the relative sales value is the selling

price at split-off.

b. If further processing is needed, the relative sales value may be approximated by

subtracting the additional anticipated processing and marketing costs from the final

sales value to arrive at the estimated net realizable value (NRV).

c. Thus, the allocation of joint costs to Product X is determined as follows:

Sales value or NRV of X

Total sales value or NRV of joint products

Joint costs

5. In determining whether to sell at the split-off point or process the item further at

additional cost, the joint cost of the product is irrelevant because it is a sunk (already

expended) cost.

a. The cost of additional processing (incremental costs) should be weighed against the

benefits received (incremental revenues). The sell-or-process decision should be

based on that relationship.

6.8 STANDARD COSTING AND VARIANCE ANALYSIS

1. Standard costs are budgeted unit costs established to motivate optimal productivity and

efficiency. A standard cost system is designed to alert management when the actual costs

of production differ significantly from target or standard costs.

a. A standard cost is a monetary measure with which actual costs are compared.

b. A standard cost is not an average of past costs but a scientifically determined

estimate of what costs should be.

c. A standard cost system can be used in both job-order and process costing systems

to isolate variances.

d. Because of the effect of fixed costs, standard costing is most effective in a flexible

budgeting system.

e. When actual costs and standard costs differ, the difference is a variance.

1) A favorable (unfavorable) variance arises when actual costs are less (greater)

than standard costs.

2) Management will usually set standards so that they are currently attainable.

a) If standards are set too high (or tight), they may be ignored by workers, or

morale may suffer.

3) Standard costs must be kept current. If prices have changed considerably for

a particular raw material, there will always be a variance if the standard cost is

not changed. Much of the usefulness of standard costs is lost if a large

variance is always expected.

f. Standard costs are usually established for materials, labor, and factory overhead.

18 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

2. Direct materials variances are usually divided into price and efficiency components. Part

of a total materials variance may be attributed to using more raw materials than the

standard and part to a cost that was higher than standard.

a. The direct materials quantity (usage) variance (an efficiency variance) is the actual

quantity minus standard quantity, times standard price: (AQ SQ)SP.

b. The direct materials price variance is the actual price minus the standard price,

times the actual quantity: (AP SP)AQ.

1) The price variance may be isolated either at the time of purchase or at the time

of transfer to WIP. The advantage of the first method is that the variance is

identified earlier.

a) Normal spoilage is considered in the calculation of standard direct

materials cost per unit.

c. Materials mix and yield

1) These variances are calculated only when the production process involves

combining materials in varying proportions (when substitutions are

allowable in combining materials).

2) The direct materials mix variance equals (a) total actual quantity times (b) the

difference between the weighted-average unit standard cost of the budgeted

mix and the weighted-average unit standard cost of the actual mix.

3) The direct materials yield variance equals (a) the weighted-average unit

standard cost of the budgeted mix times (b) the difference between the actual

quantity of materials used and the standard quantity.

4) Certain relationships may exist among the various materials variances. For

instance, an unfavorable price variance may be offset by a favorable mix or

yield variance because materials of better quality and higher price are used.

Also, a favorable mix variance may result in an unfavorable yield variance, or

vice versa.

3. Direct labor variances are similar to direct materials variances. For example, the direct

labor rate and efficiency variances are calculated in much the same way as the direct

materials price and quantity variances, respectively.

4. Factory overhead variances include variable and fixed components.

a. The total variable factory overhead variance is the difference between (1) actual

variable factory overhead and (2) the amount applied based on the budgeted

application rate and the standard input allowed for the actual output.

1) In four-way analysis of variance, it includes the

a) Spending variance -- the difference between (1) actual variable factory

overhead and (2) the product of the budgeted application rate and the

actual amount of the allocation base (activity level or amount of input)

b) Efficiency variance -- (1) the budgeted application rate times (2) the

difference between the actual input and the standard input allowed for the

actual output

i) Variable factory overhead applied equals the flexible-budget

amount for the actual output level. The reason is that unit variable

costs are assumed to be constant within the relevant range. The

flexible-budget amount is the standard amount applied for the actual

output.

ii) If variable factory overhead is applied on the basis of output, not

inputs, no efficiency variance arises.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 19

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

iii) Variable factory overhead variances

Standard Input Allowed

Actual Input for Actual Output

Actual Variable

Factory Overhead Budgeted Application Rate Budgeted Application Rate

| | |

| | |

Spending Efficiency

Variance Variance

b. The total fixed factory overhead variance is the difference between (1) actual fixed

factory overhead and (2) the amount applied based on the budgeted application rate

and the standard input allowed for the actual output.

1) In four-way analysis of variance, it includes the

a) Budget variance (spending variance) -- the difference between (1) actual

fixed factory overhead and (2) the amount budgeted

b) Volume variance (idle capacity variance, production volume variance, or

output-level variance) -- the difference between (1) budgeted fixed factory

overhead and (2) the product of the budgeted application rate and the

standard input allowed for the actual output

i) Fixed factory overhead applied does not necessarily equal the

flexible-budget amount for the actual output. The reason is that the

second amount is assumed to be constant over the relevant range

of output. Thus, the budgeted fixed factory overhead is the flexible-

budget amount. The amount applied is based on the standard input

and budgeted rate.

ii) No efficiency variance is calculated because budgeted fixed factory

overhead is a constant at all relevant output levels.

2) Fixed factory overhead variances

Standard Input Allowed

for Actual Output

Actual Fixed Budgeted Fixed

Factory Overhead Factory Overhead Budgeted Application Rate

| | |

| | |

Budget Volume

Variance Variance

c. The total overhead variance also may be divided into two or three variances (but one

variance is always the fixed overhead volume variance).

1) Three-way analysis divides the total overhead variance into volume, efficiency,

and spending variances.

a) The spending variance combines the fixed overhead budget and variable

overhead spending variances.

b) The variable overhead efficiency and fixed overhead volume variances

are the same as in four-way analysis.

2) Two-way analysis divides the total overhead variance into two variances:

volume and controllable (the latter is sometimes called the budget, total

overhead spending, or flexible-budget variance).

a) The variable overhead spending and efficiency variances and the fixed

overhead budget variance are combined.

20 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

5. Sales variances are used to evaluate the selling departments. If a firms sales differ from

the amount budgeted, the difference could be attributable to either the sales price

variance or the sales volume variance (sum of the sales mix and quantity variances).

The analysis of these variances concentrates on contribution margins because fixed

costs are assumed to be constant.

a. EXAMPLE (single product): A firm has budgeted sales of 10,000 units at $17 per

unit. Variable costs are expected to be $10 per unit, and fixed costs are budgeted at

$50,000. Thus, the company anticipates a contribution margin of $70,000 and a net

income of $20,000. However, the actual results are

Sales (11,000 units) $ 176,000

Variable costs (110,000)

Contribution margin $ 66,000

Fixed costs (50,000)

Net income $ 16,000

1) Sales were greater than predicted, but the contribution margin is less than

expected. The $4,000 discrepancy can be analyzed in terms of the sales price

variance and the sales volume variance.

2) For a single-product firm, the sales price variance is the reduction in the

contribution margin because of the change in selling price. In the example, the

actual selling price of $16 per unit is $1 less than expected. Thus, the sales

price variance is $1 times 11,000 units actually sold, or $11,000 unfavorable.

3) For the single-product firm, the sales volume variance is the change in

contribution margin caused by the difference between the actual and budgeted

volume. In this case, it is $7,000 favorable ($7 budgeted UCM 1,000-unit

increase in volume).

4) The sales mix variance is zero because the firm sells one product only. Hence,

the sales volume variance equals the sales quantity variance.

5) The sales price variance ($11,000 unfavorable) combined with the sales volume

variance ($7,000 favorable) equals the total change in the contribution margin

($4,000 unfavorable).

6) The same analysis may be done for cost of goods sold. The average

production cost per unit is used instead of the average unit selling price, but the

quantities for production volume are the same as those used for sales quantity.

Accordingly, the overall variation in gross profit is the sum of the variation in

revenue plus the variation in CGS.

b. If a company produces two or more products, the sales variances reflect not only the

effects of the change in total unit sales but also any difference in the mix sold

1) In the multiproduct case, the sales price variance may be calculated as in

5.a.2) for each product. The results are then added.

2) One way to calculate the multiproduct sales volume variance is to determine

the variance for each product as in 5.a.3) above and to add the results.

3) The sales quantity variance (the sales volume variance for a single-product

company) is the difference between (a) the budgeted contribution margin based

on actual unit sales and (b) the budgeted contribution margin based on

expected sales, assuming that the budgeted sales mix is constant.

a) One way to calculate this variance is to multiply (1) the budgeted UCM for

each product by (2) the difference between the budgeted unit sales of the

product and its budgeted percentage of actual total unit sales. The

results are then added.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 21

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

4) The sales mix variance is the difference between (a) the budgeted contribution

margin for the actual mix and actual total quantity of products sold and (b) the

budgeted contribution margin for the expected mix and actual total quantity of

products sold.

a) One way to calculate this variance is to multiply (1) the budgeted UCM for

each product by (2) the difference between actual unit sales of the

product and its budgeted percentage of actual total unit sales. The

results are then added.

6. Journal entries. Variances usually do not appear on the financial statements. They are

used for managerial control and are recorded in the ledger accounts.

a. When standard costs are recorded in inventory accounts, variances also are

recorded. Thus, direct labor is recorded as a liability at actual cost, but it is charged

to WIP control at its standard cost for the standard quantity used. The direct labor

rate and efficiency variances are recognized at that time.

1) Direct materials, however, should be debited to materials control at standard

prices at the time of purchase. The purpose is to isolate the direct materials

price variance as soon as possible. When direct materials are used, they are

debited to WIP at the standard cost for the standard quantity, and the materials

quantity variance is then recognized.

b. Actual overhead costs are debited to overhead control and credited to accounts

payable, wages payable, etc. Applied overhead is credited to an overhead applied

account and debited to WIP control.

1) The simplest method of recording the overhead variances is to wait until year-

end. The variances can then be recognized separately when the overhead

control and overhead applied accounts are closed (by a credit and a debit,

respectively). The balancing debits or credits are to the variance accounts.

c. The following are the entries to record variances. Favorable variances are credits

and unfavorable variances are debits:

1) Materials control (AQ SP) $XXX

Direct materials price variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Accounts payable (AQ AP) $XXX

2) WIP control (SQ SP) XXX

Direct materials quantity variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Direct labor rate variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Direct labor efficiency variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Materials control (AQ SP) XXX

Wages payable (AQ AP) XXX

3) Overhead control (actual) XXX

Wages payable (actual) XXX

Accounts payable (actual) XXX

4) WIP control (standard) XXX

Overhead applied (standard) XXX

5) Overhead applied (standard) XXX

Variable overhead spending variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Variable overhead efficiency variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Fixed overhead budget variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Fixed overhead volume variance (Dr or Cr) XXX

Overhead control (actual) XXX

6) The result of the foregoing entries is that WIP contains standard costs only.

22 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

d. Disposition of variances. Immaterial variances are customarily closed to cost of

goods sold or income summary.

1) Variances that are material may be prorated. A simple approach to proration

is to allocate the total net variance to work-in-process, finished goods, and cost

of goods sold based on the balances in those accounts. However, more

complex methods of allocation are possible.

e. Several alternative approaches to the timing of recognition of variances are

possible. For example, direct materials and labor might be transferred to WIP at their

actual quantities. In that case, the direct materials quantity and direct labor

efficiency variances might be recognized when goods are transferred from WIP to

finished goods.

1) Furthermore, the direct materials price variance might be isolated at the time

of transfer to WIP. These methods, however, delay the recognition of

variances. Early recognition is desirable for control purposes.

6.9 TYPES OF BUDGETS

1. A budget (profit plan) is a realistic plan for the future expressed in quantitative terms. Top

management can use a budget to (a) plan for the future, (b) communicate objectives to all

levels of the organization, (c) motivate employees, (d) control organizational activities, and

(e) evaluate performance.

a. The annual budget should be based upon an organizations objectives. Thus, it is

usually based on a combination of financial, quantitative, and qualitative measures.

2. The operating budget sequence is the part of the master budget process that begins

with the sales budget and ends with the pro forma income statement. It emphasizes

obtaining and using resources. It includes budgets for sales, production, and cost of goods

sold.

a. Other budgets prepared during the operating budget sequence are those for (1) R&D,

(2) design, (3) marketing, (4) distribution, (5) customer service, and (6) administrative

costs. These budgets, the sales budget, and the cost of goods sold budget are

needed to prepare a pro forma operating income statement.

3. The sales budget is usually the first budget prepared, so accurate sales forecasts are

crucial. The next step is to decide how much to produce or purchase.

a. Sales are usually budgeted by product or department.

b. Sales volume affects production and purchasing levels, operating expenses, and

cash flow.

4. The production budget (for a manufacturer) is based on the sales forecast, in units, plus

or minus the desired inventory change.

a. It is prepared for each department and is used to plan when items will be produced.

b. When the production budget has been completed, it is used with the ending

inventory budget to prepare three additional budgets.

1) Direct materials usage, together with beginning inventory and targeted ending

inventory data, determines the direct materials budget.

2) The direct labor budget depends on wage rates, amounts and types of

production, employees to be hired, etc.

3) The factory overhead budget is a function of how factory overhead varies with

particular cost drivers.

SU 6: Managerial Accounting 23

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

5. The cost of goods sold budget reflects direct materials usage, direct labor, factory

overhead, and the change in finished goods inventory.

6. The financial budget sequence is the part of the master budget process that incorporates

the cash budget, capital budget, and pro forma financial statements. It emphasizes

obtaining the funds needed to purchase operating assets.

7. The capital budget is not part of the operating budget because it is not part of normal

operations. The capital budget may be prepared more than a year in advance to allow

sufficient time to

a. Plan financing of major expenditures for long-term assets such as equipment,

buildings, and land

b. Receive custom orders of specialized equipment, buildings, etc.

8. The cash budget is vital because an organization must have adequate cash at all times.

Even with plenty of other assets, an organization with a temporary shortage of cash can be

driven into bankruptcy. Thus, cash budgets are prepared not only for annual and quarterly

periods but also for monthly and weekly periods.

a. A cash budget projects cash flows for planning and control purposes. Hence, it

helps prevent not only cash emergencies but also excessive idle cash.

b. It cannot be prepared until the other budgets have been completed.

c. Almost all organizations, regardless of size, prepare a cash budget.

d. It is particularly important for organizations operating in seasonal industries.

e. Cash budgeting facilitates planning for loans and other financing.

9. The following is a summary of the operating budget sequence for a manufacturing firm

that includes all elements of the value chain:

R&D Budget

Design Budget

Marketing Budget

Sales

Budget

Ending

nventory

Budget

Production

Budget

Direct Materials

Budget

Direct

Labor

Budget

Factory

Overhead

Budget

Pro Forma

ncome

Statement

Cost of Goods

Sold Budget

Distribution Budget

Customer Service Budget

Administrative Budget

24 SU 6: Managerial Accounting

Copyright 2008 Gleim Publications, Inc. and/or Gleim Internet, Inc. All rights reserved. Duplication prohibited. www.gleim.com

10. The following is a summary of the financial budget sequence:

Capital

Budget

Pro Forma

Statement

of Cash Flows

Pro Forma

ncome

Statement

Pro Forma

Balance Sheet

Cash

Budget

11. Once the individual budgets are complete, budgeted financial statements can be prepared.

These pro forma statements are prepared before actual activities commence.

a. The pro forma income statement ends the operating budget sequence. It is the

pro forma operating income statement adjusted for interest and taxes.

1) It is used to decide whether the budgeted activities will result in an acceptable

level of income.

2) If it shows an unacceptable level of income, the whole budgeting process must

begin again.