Eric Gill

Diunggah oleh

JenniferLawrenceJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Eric Gill

Diunggah oleh

JenniferLawrenceHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

:i

:l

il

Eric

Gitl in Jerusalem:

Artistic \\Iorh artd,

Sp iritual Affirmatiorl

By GnscoRY T Gnaalps

An"

bright January afternoon in 1993I entered for

\-/the first time the Rockefeller Museum in East

Jerusalem.' More an academic institution than a

museum, the building now is the home of the Israeli

Antiquities Authority. Oddly, however, I noticed

familiar-looking sculptures around the courtyard

perimeter and gallery signs in a somehow familiar

lettering sryle. Both looked vaguely like the work of

Eric Gill, but I quickly dismissed the idea, for I had

never read that Gill visited Jerusalem. Why would

Gill have done sculptures for what I thought was

originally an American institution named for John D.

Rockefeller, Jr.? But such questions only indicated

the degree of my ignorance and confusion about the

history of Jerusalem, with its complex pbysical,

political. and relisious organisation and multiple

layers of its long history.

As I discovered, however, the sculpture and the

lettering are, indeed, the work of Eric Gill, the

eccentric British letter-cutter, type designer, book

illustrator, sculptor, and essayist who lived from 1888

to 1940. There are actually ten relief sculptures by

him within the inner courtyard and a larger one oyer

the enrance. He and his assistant, Laurie Cribb, also

did the lettering for the gallery signs. All this work

was done in 1934, on the first of two trips Gill made

to Jerusalem toward the end of his life. He visited a

second time in 1937. His experiences in Jerusalem

are well documented, for he kept fastidious records in

the form of letters, diaries, daybooks, ledgen, expense

booklets, copies of estimates, scrapbooks, and

drawings.!' Jerusalem is'also the title of a chapter in

his autobiography. Considering the brevity of his

visits, he did aconsiderable amount of work there that

represented the full range of his talent in sculpture,

lener-cuning, drawing, and type design. In srudying

Gill, however, one can easily remain ignorant of these

because they are little covered by his biographers.

Furthermore, criticism of his work thcre is dismissive.

Few like'an Arabic typeface he designed, and &e Rockefeller

sculptures are referred to by one critic as '...perhaps minor

works in Gill's oeuwe.... The rcsults, as far as one cqn

judge

from photographs, are a good workmanlike job."'.

This

neglect of his Jerusalem experience by critics and biographers

is completely at odds with Eric Gill's own opinion. Jerusalem

was to Gill a revelation

-

a turning point

-

in his life.

Jerusalem is, indeed, an extraordinary city. It is of

spirirual significance to ttrrce of the world's grcat religions

-

Catholicism, Islam, and Judeism. For travellers and visitors, a

lAxlltAEv aa66 rr rr

-a

trips

:

.:.

:4

j;

.-.:

1i

t

a:

:+

1',

a

!

..1

ja

,a

v

*

.T

:{

,j

t

i

t

I

I

t

I

i

Studio Portait of Sir Arthur Grenfell Wauchope.

Photo credit: The Black Watch Museurn, Perth.

journey

to Jerusalem is often a singular and inspirational

experience, and many have written eloquently of their

experiences there. One characterisation appropriate to our

story is that of Sir Ronald Storrs, military governor of

Jerusalem between l9l8 and 1926, who wrote: "I cannot

pretend to describe or analyse my love for Jerusalem.... There

are many positions of greater authority and renown within and

without the British Empire but in a sense I cannot explain

there is no promotion

after Jerusalem."'. Many of the British

officials w-ho served in Palestine during this period had a

similar dedication to their assignment and were renewed

by

Jerusalem's spirituality. Considering that Gill's religious

belief was central to both his life and his art and that he had

converted to Catholicism at age thirty-one, a trip to Jerusalem

seems perfectly fitting

-

almost of necessity"

Without the commission at the Rockefeller, however.

Gill would probably not have gone there. To quote one

biographer, "Eric lacked the curiosity of the bom traveller."''

He admits this himself: "I'm no

Isic]

particular good at

travelling. . .l don't like sight-seeing or acquiring information

and I am no good at foreign languages."'' Although trips to

Jerusalem and the Holy Land have long been popular for the

British, Gill, clearly, would never have planned such a

sightseeing trip. Thus, he visited Jerusalem almost as if by

fate. As fate would have it, these trips were most significant

to Gill. According to biographer Fiona MacCarthy, the

experience divided Gill's life into "pre- and post-Jerusalem"u'

phases. In the post-Jerusalem phase, Gill became ever more

determined to speak out against what he called "capitalist-

industrialism," writing,

*Hence

forward I must take up a

position even more antagonistic to my contemporaries than

that of a mere critic of the mechanistic system.'a'

The First Yisit

Gill's visis to Jerusalem came at a portentous time in

that city's modern history. He came during what some

historians consider the second and more violent half of the

British mandate

-

a time of banditry, shifting alliances,

rising tensions between the home government in London and

British officials in Palestine, increasing Jewish immigration,

and a significant transformation from an Arab and agrarian

society to a Jewish and industrialised one. This was a time of

struggle between Arabs and Zionists for control of a

homeland, a struggle that continues today.

Gill's first trip to Jerusalem took place between March l0

and July 27, 1934 when he went there to carve ten sculptural

panels for the Rockefeller Museum, an archaeological edifice

designed by the British architect Austen St. Barbe Harrison.

32 ANTIQUAHIAN BOOK MONTHLY

Harrison had most likely heard of

Gill through fellow architect Erich

Mendelsohn, who in turn knew of

Gill because he had been asked in

1933 to teach typography at the

Acad6mie Europenne M6ditenane,

a propo3ed modernist art school on

the French Riviera. The faculty was

to include Mendelsohn, as well as

Paul Hindemith and Serge

Chennayeff. Funding for the school

never materialised, but Mendelsohn,

an architect and a Zionist who

designed many buildings in Israel,

most likely recommended Gill to

Hanison.

The Rockefeller Museum is the only

cultural institution founded by the

British during the mandate. It was

the gift of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.,

who gave two million dollars for its

building and maintenance in 1928. It

was intended as an archaeological

institute, "throwing light on the past

of man in Palestine."t' Austen St

Barbe Harrison, then serving as the

architect to the government of

Palestine, was selected to design the

museum despite suggestions by the

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) that the design be

opened to an international competition. Gill began drawings

for the sculptures at his home in Pigots beforc he left for the

Middle East. At one point, Sir George Horsfield, chief

archaeologist at Jarash (in modern-day Jordan), came to

confer with Gill on the project. Thus began Gill's work and

prepararion for his trip.

-

Despite his self-characterisation as a poor traveller, Gill

quickly became enthusiastic about the trip. He made his way

to Palestine by boat, accompanied by his assistant Laurie

Cribb, on the S.S. Rajputana. The ship stopped at Tangiers,

where Gill was attracted to the robes worn by the Arab men,

and then went on to spend a day in Marseilles, ". . .one of the

most lovely cities in the world....'D' He landed at Port Said

on March 21, 1934, then boarded a train and travelled on to

Lydda, where the tracks split, one for the coast and the other

for Jerusalem. To his wife, M4ry, Gill wrote: "We are in

Palestine

-

very near Jerusalem. It is as you'd expect

-

two

extremes meeting. Camels and mules and donkeys. . .and

young men and women and children exactly as all the Bible

pictures. . . alongside, power stations, soldiers in khaki

etc...."'o'

He arrived in Jerusalem on March 22 and went directly to

Harrison's home for brcalfast and a bath. He was then taken

to the Convent dei Dominicains, a French instinrte, that also

supported an important archaeological institute, where he

stayed initially. The next day he went to the Rockefeller and

began work, first rcworking his drawings for the panels. Thus

began a busy schedule for Gill that mixed days working

extensively at the museum with travels to historical and

religious sites in Jerusalem and Palestine. In his diary he

noted that a typical day involved rising at 6 a.m., going to

Mass at 6:30, having breakfast, and starting work at 8am.

Lunch was at noon and he worked until 5 or 5:30pm. Writing

letters occupied his time until 7:30, then it was dinner time.

He customarily read for an hour after dinner and was asleep

The Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem. Photo credit The Black lYalch museum, Perth.

JANUARY 1999

Final Sketchfor EgYPt.

Photo credit: UCLA'

interested in Islamic art and culture. (Today there is a Mayer

Institute and Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem.) Exactly

when and how discussions for this typeface began is unclear,

although Mayer probably first saw Gill's efforts with Hebrew

in the gallery signs at the Rockefeller. Regardless, Gill notes

in his daybook that drawings were sent to Mayer in April

1937, and he made an entry in his ledger book for them on

December 31, 1936. He carried on work with this project

through 1937.

The Second Trip

While this Hebrew typeface project certainly kept the

1934 trip to Jerusalem present in Gill's mind, the spirit of the

city also had a profound impact on him and motivated him to

return. In 1937 he wrote to his friend, Desmond Chute, in

Italy and suggested a trip to Jerusalem together. Gill

expressed eagerness to return, drawn by the hot weather and

because the "Holy Land remains holy."

"'

Although the trip

with Chute never materialised, Gill himself did retum in 1937.

The second trip to Jerusalem, which took place between

May and July of 1937 was funded by Gill's friend, Graham

Carey, and is referred to by Gill as a holiday. Although he

had work and projects there, they were less demanding than

the Rockefeller sculptures and not as settled at the time of

departure. This time he travelled with his wife, Mary; they

went by train through Europe, and then took a ship from

Trieste to Haifa. They clearly enjoyed themselves together

-

this trip seeming to him less of a family affair and more like a

second honeymoon. Whilst there, Gill also flew to Cairo rvith

Austen Harrison.

Although the projects on this second trip were less

demanding, they were certainly more varied. Furthermore,

they illustrate the extent to which Gill had become well-

connected within the British circles of influence in Jerusalem.

First, he worked for Dr. J.C. Strathearn, warden of the

Ophthalmic Hospital of the Order of St. John. Here he carved

two tablets for the hospital, one in memory of Genevieve

Lady Watson, a benefactor, and the other in tribute to the

work of William Edmund Cant, a doctor at the hospital. Gill

was asked by Sir Arthur Wauchope to carve a stone at the

Scotch Church in Jerusalem in memory of the men of the

34 ANTIOUARIAN BOOK MONTHLY

Sketclt: Israel Brought Their l-aws.

Photo credit: UCI"4

Black Watch, Royal Highlanders

(to which Wauchope

belonged), rvho had died in battle in Palestine. He also did a

carving for the Haifa Government Hospital, a building

designed by his friend, Erich Mendelsohn. There was also a

facade for the Barclays Bank in Tel Aviv, most likely for

Austen Harrison.

Gill seems to have become involved in designing

Postage

stamps for the mandatory government' as well, although

details on this activity are not numerous. He notes in his diary

of the trip that he met on May 19 with Mr. Webster, P.M.G.

(Post Master General, presumably) about postage stamps'

Later, he notes starting drawings for the stamps on the voyage

home; but no images survive.

Gill was also engaged during this trip on two typeface

projects: continuation of work on the Hebrew typeface for

Mayer, as *'ell as initial discussions on an Arabic typeface for

Sir Wauchope. Gill had sent drawings of the Hebrew tyPe to

Mayer in April 1937, and he was now refining this type with

Mayer's input. Punches were made by the Monotype

Corporation. while trial castings were made in Enschede,

Holland. Monotype approved the font in February 1938,

listing it as Series 487.

The other project was an Arabic typeface, commissioned

by Sir Wauchope for the new Government Printing Offrce. Its

building was finally in the process of construction in 1937

after Sir Wauchope had been long engaged in convincing

London of the need for the facility, with correspondence and

estimates dating back to 1932. After he received permission

to build, it rvas again Austen Harrison who designed the

structure. In view of his dedication to this project" it seems

natural that Wauchope wished to inaugurate the operation in a

special way by commissioning its proprietary Arabic

rypeface. Gill submined drawings to Wauchope in September

1938. Holever, many critics

-

Particularly

Arab

calligraphers to whom the drawings were shown

-

denounced the design, and the face was never cut.

Gill was also interviewed on the Palestine Broadcasting

Service during this trip. Although no detailed record of this

program has been found, he does indicdte in a letter to

Graham Carey that the title was "Art in England, as it seems

to me." In this lecture and interview, Gill ". .

'.took

the

JANUARY 1999

Gill's sketch of Gibraltar

whilst travelling to Israel in

1934. Photo credit: UCLA

opportunity to rub in the connections between art. . .and

commercial industrialism."

15'

Finally, Gill, apparently, made friends with David

Ohanessian, an Armenian originally brought to Jerusalem

from Damascus to make tiles for a British-sponsored

restoration of the Dome of the Rock. Gill first records a visit

to Ohanessians's on May 20, to see his pottery works. He

subsequently returned numerous times, making drawings of

the old city from the studio window, as well as drawing on

pottery. In a letter, Gill writes how, regardless of the value of

the drawings themselves, doing them provided ". . .a fine way

of staying put and thus really soaking up the scene."

'''

This

is an interesting statement for a man who, according to

biographer Robert Speaight, had no taste for landscape.

Jerusalem seemed to calm Gill and allow him periods of

reflection.

As during the first trip, Gill travelled to various biblical

sites, although less extensively than before. He returned to

Bethany, Jericho, bathed in the Dead Sea, had lunch on the

banks of the Jordan, and returned to Ein Karem. However,

his major excursion was to Cairo. Gill flew there with Austen

Harrison, while Mary stayed in Jerusalem. This trip occupied

five days and included visits with John Gayer-Anderson, a

well-known Englishman living in Cairo whose lovely and

well-restored Cairen home is today open to the public as a

museum. The men seemed to have a grand time of it, going to

a casino and seeing "arab dancers." In addition, they visited

numerous churches, went to Sultan Hasan Mosque, visited El

Azha University, and had a Turkish bath. Gill went

frequently to the suqs to be measured for another galaba. Of

the old city Gill says, "Cairo itself is a corupt and bad old

city

Q

should think) and very hot and enervating."

r7'

From

Cairo he and Harrison flew to Jaffa, walked to Tel Ayiv, then

returned to Jerusalem by car on June 9.Just before leaving

Jerusalem, Gill finished both the Scotch inscription and that at

St. John's Hospital. He and Mary left Palestine on June 28

and were back in London on July 12.

Viewpoints

In his autobiography, Gill writes that "Palestine was the last

of the revelations vouchsafed to me. It confirmed and

JANUAFY 1999

Sketch of Gill's entitled

"Tombs

of SS

Martha and ltzarus at Marseilles"

frotn first

trip. Photo credit: UCLA.

enfolded all the others."

t8'

Debpite such a powerful

statement, little is recorded by Gill's biographers about the

trips and none has sought to understand them in historical

context or interpret their significance to Gill personally. One

hint of their importance, however, comes in the introduction

to Eric Gill: Jentsalem Dia4', a series of letters compiled by

his wife and published posthumously. In her brief

introduction to the book, Mary writes, ". . .The Holy Land,

which he regarded as much a pilgrimage as a

journey to some

work to be done."e' Thus, although Gill initially went to

Jerusalem only because he had work there, his trip became

something more. Indeed, it had a strong spiritual impact and

can be fairly described as a sacramental experience. Only in

his autobiography, written just months before his death, does

Gill elaborate on the spiritual impact of Jerusalem: "In the

Holy Land I saw a holy land indeed; I also saw, as it were eye

to eye, the sweating face of Christ."

''

Further, ". . .while I

never saw or imagined anything more lovely than the Holy

Land

-

whether you think of it as a land or as human

habitations, so also I never saw anything less comtpted by

human pride and sin. And I understood as never before the

vinue of poverty and how peace on earth can have no other

basis."

:''

Infused with rediscovery of the power and virtue

of poverty, Gill rerurned from Palestine more determined than

ever to defeat "capitalist-industrialism," even if so doing

required that he become more antagonistic towards his

contemporaries.

Such declarations, however, are strikingly at odds with

events actually taking place in Palestine at the time of the

visits. Palestine in the 1930s was a dangerous place, where

innocent people on all sides

-

Arabs, Jews, and British

-

were killed in the streets. As noted before, during this period

tensions were at their highest and the British themselves were

the focus of considerable violence. Sir Arthur Wauchope, as

High Commissioner, was at the centre of this maelstrom. ln

fact, Wauchope's tenure has been somewhat discredited for

his alleged failure to show the required firmness in dealing

with the Arabs. Gill certainly knew of the tensions and was

aware of the violence, and also had the advantage of beirig

privy to official reports. He notes "talking politics" a numhr

of times in his 1937 travel diary with Hanison, Wauchope,

ANTTOUARIAN BOOK MONTHLY 35

and others. In short, there could be no illusions on his part as

to the nature of the situation.

One explanation for Gill's characterisation of Palestine as

holy and uncorrupted is the romantic, orientalist, and

imperialist British view of the Arabs as being simple and

unspoiled. As R.D. Kernohan writes in The Road to Zion,

one's associates or colleagues are important in forming the

opinions of the "modern pilgrimage" to Palestine: ". . . the

advice he receives on the spot almost invariably reflects the

politics and nationality of the adviser.

2'

Gill's advisers were

men like

Wauchope who

were sympathetic

toward the Arabs

at this time, so

Gill himself

developed a bias

toward the Arab

viewpoint in

Palestine. While

he appreciated

that tbe Zionists

had made

important

improvements,

such as providing

a reliable water

supply and

expanding the

usable

agricultural land,

his anti

Sketch of Mar Saba, 1%4 fip.

Photo credit: aCIA.

industrialist

stance biased him

against them and

strengthened his

stereotypical view

of unencumbered

traditional Arab life as simple and unspoiled.

Not only does his characterisation of Palestine as

unspoiled appear odd, but his expressed opposition to

capitalist-industrialism grossly overlooks his own role in

Palestine. First, Gill worked in Palestine as a result of

connections with influential people. His introduction came

through Erich Mendelsohn, the influential Zionist and

architect; he was chosen by the architect to the mandatory

government, Austen Harrison. Finally, he became friends with

the high commissioner. Sir Arthur Wauchope. Further,

just

as

his other large sculptural works of the period

-

the BBC

building in London or the League of Nations in Geneva

-

were projects for large corporate or governmental bodies,

likewise, the Rockefeller Museum was a monument financed

by none other than a millionaire, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In

addition, as the sculptor at the Rockefeller, Gill was quite

literally an employee of the British mandatory government,

and the building was a clear expression of British imperialist

power, with its contrived effort to depict harmonious and

balanced historical influences in Palestine. Gill, therefore,

was not expressing his own interpretation of historical events

in Palestine, but rather lending his hand to communicating the

ideas of those in power. As Nitza Rosovsky writes about the

Rockefeller: "Here Harrison created a building that fulfilled

the highest possible role of public architecture, namely to

express the spiritual ideals that its sponsors and donors wish

to rcpresent."

a''

If not capitalist, these spiritual ideas were

36 ANTIOUARIAN BOOK MONTHLY

certainly heavily laden with British imperialism.

Tfuee and a half years after his return frorn the second trip

to Jerusalem, Gill died of lung cancer at the age of frfty-eight.

Robert Speaight wrote concerning Gill's trips that "Palestine

was a viaticum."

2''

The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia

defines viaticum as "Holy Communion given to those facing

life-threatening circumstances in order that they may be

imbued with God's grace on their

journey

into eternal [fe." A

colleague has suggested that the tenn can also be inteqpreted

to mean "food for the

journey

to the next life." This view is a

thought-provoking description of Gill's Palestine trips. Just

months before his death, during the spring and early surlmer

of 1940 when he was suffering from congestion of the lungs,

Eric Gill finally offers in his autobiography an assessment of

what Jerusalem meant to him and reveals the degree to which

it was, indeed, food for his next life. The city had become a

metaphor of the spiritual, un-industrialised, anti-capitalist

community he had espoused throughout his life and had

provided the spiritual experience that prepared him for his

afterlife.

ii, ir

l.Much of tbis material is available at the William Andrewq

Q!a*

Memorial Library, an off-campus library that belongs

1o

the

University of California at L,os Angeles. Another valuable collection

is at the Gleesoa Library. Univenityof San Francisco. -,

i.

,

,,-i,,

.

2. Malcolm Yorke, Eric GiIl: Man of Flesh & Spirir (London:

Con'stable & Co., Ltd., l98l), p.236.

::'. ; -

'

3. Sir Rooald Storrs, Ifte Memoirs of Sir Ronald Srorrs (New York:

G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1937), p.465.

.',

.

4. Robert Speaieht" The Ufe ol Eic Grl ([,ondon: Metbuem & Co.,

Ltn.,1966), p.244.

5. Eric Glll, Autobiography

(London: Lund Humphries Publishers,

1992),p.251.

.,,,,:,

6. Fiona MacCarthy, Eric GiII: A Inver's

Quest for

An & God (New

York: E.P. Dutton, 1989), p.263.

7. Gill, Autobiograplry, p.257.

, .-,.

p.387.

. .'..1-;i{,.

l6Jbid-, p389.' r,

-,1-'

17. Shewring, IrScrS, p388.

18. GIII, Autobiogrdihy, p.253.

19. Gill, Jerasalem Diary.

20. Citll, Autobiography,

9253.

21. Ibid, p.256.'

; ;.:,,

:

22. R.D. Kernohan,'.'Zhe Road to Zon TraigllCis to

I-arul of Israel (Edinbrngb: The Handsel Priss L!d: 19?5.

23. Nitza Rosovsky, City of the Gre:at King

ii

Massachuse(s: Harvard Univenity Press, 1!p6),p.439.

24. Spefieht, Iife of Eric GiIl,p.24.

14. Letter from

p41g,Gill to Desmond.Chutc_.24 Janulrv-1937.

Gleesoo Library;Uoivittity of San Franciscorirj;E,

],,i.ffi

i

I S.Lctter from Eric- Gill to Graham -Carey.'? Julyrl

9iTr::.YdFr

Shewring, d., I-eneyi of Eic Grtt (Ipndon::J-o-*th"6"gp,ri:tpl,

6-, ll

So^^/s

In tht 1930s, tht grca!

|,pr dcsigncr l:rit Gill tnthustns!icnll.y'trorkr'd oti an Arabic t.yplau. ll was doond.

Dressed in sandals and a djellabalr and wearing a khafiya, the British

typograplrer and sculptor Eric Gill traveled to Jerusalem in 1934. r\s he

wrote in his autobiography, he felt as though he rvere r.r'alking rt'ith tlie

Apostles and living in the Bible. Brouglrt there to carve sculprures for a

nel,r'museum, Gill took tea in the teahouses of the OId City, relaxcd

'n

'

Turkish bath at day's end, or rvalked, as Christ did, to Gethsemane, in tlie

Judean

desert and to

Jacob's

well. This trip and a later oue in 1937 affecteci

Gill profoundly, serving to strengthen his religious convictions and tc

inspire hirn in his role as an outspokeu critic o[ capitalist socien. The vis-

its were equally rich and inspirational to him as an artist; he did an enor-

mous amount of nork in

Jerusaiem,

including sculpture, draning, cut-

ting memorial stones, and designing fype. This storv follon's the desisn

of his Arabic typeface, a rypeface that he never cornpleted.

in 1933, Gill was asked to teach at the Acad6mie Europ6enne M6diter-

ran6e, a proposed moderni.st art school on the French Riviera l'liose fac-

ulty later included Paul Hindenrith, Serge Chermaleff, and Eric Mendel-

sohn. Although funding for the school never materialized, Gill had the

opportunity to meet Mendelsohn, the architect and Zionist who de-

signed many buildings in

Jerusalem

and, later, elsewhere in Israel. It was

Mendelsohn who most likely recommended Gill as the sculptor for tlie

new museum in

Jerusalem.

Shortly after the demise of this Acad6mie project, Gill journeyed to

Palestine in the spring of 1934 to carve the sculptures for the Rockefeller

Museum inJerusalem. His work at the museum included carving ten wall

panels, the fountainhead in the central courtvard, the q'mpanum panel,

and the signs in Hebrew, Arabic, and English. In Ma1, 1932 he returned

IO8PRINT

to Palestine for a rvorking vacation, carving a sculpture for St.

John's

Hos-

pital in lerusalem and traveling to Cairo. It rvas on this second trip that he

receiled a comnrission to design an Arabic q,peface.

The first menlion of the t1'peface appears in hisjournal account of the

trip on June 12.Ig37,u4rich reads:

'To

Gov't Ilouse for lunch rr irlr MEG

and H.[. Talked about printing, arabs and all sorts." The entrl refers to

Cill's rrife, ivlarr (lVlEG), and to Sir Arthur \Vauchope, l-lis [xcellency

(H.E.). lt rvas \\'aucltope, then British High Connrissionel in Palestinr'

u4ro contracted the typeface for the Covernment Printing Office ir

Jerusalem.

lndeed, Gill arrd Wauchope \\'ent to thc printinl office to-

gether to further discuss the project, as Gill's journal entrv oi June 16 in-

dicates. From the letter sent by Gill to Wauchopc u'ith his {rrst drarr'ings,

it iS clear that the g,peface was specificalll designed for linotlpe and

monon pe machines at this printing office.

Arabic is a Semitic language and, like Hebrerr', is nritten from right to

left. Its alphabet consists of 28 letters; all are consonants. There are no

capital leners or punctuation marks. All the letters have four forms: ini-

tial, medial, final, and separate (see

Gill's table for these in Fig. 2). In

other rrords, the shape of letters changes somel'hat depending upon

their position rlithin a rvord. As a result, there are significanth,more than

28 characters to be designed u,hen producing an Arabic q'peface. The in-

creased number of

rype

sorts required is not an insurmountabie prob-

lem rvith handset t1,pe, but it is a serious limitation rr'ith monon'pe and

linon'pe because of limited space for matrices.

Fig, 4 shorvs Gill's loose pencil drawings of individual Arabic charac-

ters. Presumabh. this is how he began-bv becoming farniliar rr'ith the

T::t;

gj

I

,-:.:-l

.Lt

.,

!1^'

I

,b

tr(

\-:rt

\-?{

.L

J

g->

5

IA

,\

a-J

-

* aFg)

I

I

t

-l

.,

t

t

+

.a

.t

.i

l. Sample of i:ic Gill's unceveioPed

a:aric tvpeface Once the typeface was

c:avn. Gill testeci leiter conbinatlons

src): as these Courtesy of 5t'Bride

Pr:rt:ng Lib:a:;. Londc;.

2. Gill s table ci lhe four Arabrc

.e::erforms. ;:.:::a;, neCtal. 6nal anci

separate Cour:esy of the Wiliiam

.:-:.d:ews Cia:i. Library oi UCLA.

3. G:ll coilect:c exanpies c: Arabtc

:'.':ography such as this one io helD

s.:a:e hrs vrs:on of hrs own Arabtc

:-':e:ace Lo:::esv cl the wlillam

.-:.C..r, Cla:k i-rtrary of UCLA

letterforms. Then canre a much more careful rendering of individual

.{rabic lettos. Fig. 5 reveals Gill's precisell outlined letters, partially

blackened in pencil. His ren'orking of certain letters is apparent in his ex-

tending the tail on some and shortening the descenders on others. Next

came a sheet of individual letters done in pen and ink (Fig.

6). Pieces

\\'ere carefull), cut out of this page and rearranged into words. He pro-

dlrced a sheet of rthat appear to be entire \\'ords in Arabic, all carefull)'

and evenh blackened in ink with a comment b), Cill:

"Note:

These are

not intended to be real \\,ords but onh, to sho\\, combinations and let-

ters." This sheet is dated October 1, 1937, and is signed CE, the initials

reading from rigirt to left, mimicking Arabic.

After this stage \ras completed, Gill evidentlv made a photostat of the

original sheet to produce a clean copy u'ithout the outline of the cut-

tings. On this copv he carefulli, made final alterations, shortening the

stroke of certain final letters and terminating u'ith a serif rather than a

calligraphic flourish. He also removed the flourish from certain descen-

ders. He shortened the descender on the initial a or alf, and in one case

he added a letter entirely. Undoubtedly, th.is is the drawing he sent to Sir

\\huchope (Fig.7).

In his letter to \Arauchope accompanying the drau'ing, Gill wrote:

'As

\ou will remember, you commissioned me to make this design as the re-

sult of our conversation in which i said that it $,as a great pity that the ex-

isting Arab q?es were merely imitations of Arab handwriting and that

nothing had been done by typefounders to reconcile the wrinen forms of

Arabic letters with the exigencies of printing type." Thus, although \{au-

chope commissioned the t)?e, it was Gill rvho initiated the project as a

t\-

{g

-i-

ltr

)

-r-

e

(j-

*

\-

-l

I

)

-\

-t

-=\-

>

-+

=\

).,

'

.>a

l

-1

-la

-\t\

g*

-=\

*l

-;-c

_?

.-,

L

_b

;

,

U

I

/

).

J

-.e

_b

-b

!

..

-l

-;

-F

\

J

-6

'

,

J,

)i'

.E

i

i

\

J

-A

1'

{v

<'

!i

i

5t

./

r'

\

0o_,

t\J

\

d\.

h

4

\

JJ

I

zL, a"

_l

r'

c

1

-dr'

(:rr'Drrs-'L

:L)

it

PRINTI09

I

1

li:

^4.2

F-;-

+-'-

I(

,t .,

', I

i;

,i

i

t

-\*/g

-

12- .r\

vg

;

{3,v

**

$t

x4

,

!/2

.--- '\]l

"=';/'

t{

/\

?

it

.tl

=

t

t$\

).]-

I

-..

i

'.t

i:\

I'

c\

.ti

ri

i

i

l\

a..\

-;:Q!--

-,

"-

^-

L3"-,

\

\-

{

3,?

*-

/y

_-

4:

E1[-

l(

i"

\1,

v,

-t;r'E

\

L

Ji

F:-),

./

._:r

v

AA

Lq

,7y'_

5.

U

llOPRINT

re$uJt of his interest in the inherent typographic comPlexities posed b1,

Arabic. That interest seems natural given his presence in Palestine, the

source of Semitic languages and alphabets and an inspiring place for any-

one involved in $,pography.

On Mav 19, 1934, for example, Cill visited

the British excavations in

Jer:'ish,

in present-dayJordan, and dreu' Rontan

alphabets from the large inscriptions orl I{adrian's arch.

Another irr.spirltion n'as the British ivlitndate lau'establishirtg Enslish,

Arabic, and l-lebrerl as Pllestirte's three official languages. Cill sart sigrts

put up by the British after \{orld \{ar I to ntark intersection.s in tire Old

Cin'and he was required to carve such signs at the Rockefeller Musetrm.

.

But tlre most influerrtial source of Gill's entlrtrsiasrn for.\rlbic culture

and its alplrabet rlas the Donie of the Rock, the gold-dorned buildirtg

that donrinates the

Jelusalenr

sltylirre in its position on a lrrrge plaribrm

krrorr'n as rhe Ilaram al-Sharif, or Noble Sattctuary. Built in 691 ,r.tr. by

Abd al-l\4alik, the Urnal'yad governor of

je

rusalenr, the Donre of the Rock

n'as described bv Cill in lris autobiograplrl' as

"

. . . the ntost beautiful

place I have evc'l'seen . . . tlre nrost civilized, tlte tttost ctrltLtred, tlte ntost

quiet and serene, tlte ntost spaciott.s, tlte rnost spiritualll'pervaded place

norr rernaining in the rvhole u'orld." I-le trndoubtedl)' studied and tlas

influencecl by tlre earlv rttotrtttttetttal irrscriptions on tlre interior perirne-

ter ol tlre dorne.

Despite his irrspired ellorts, Cill's Arabic t1'peface renrairrs his ortir clc-

siqn tlrat \vas nevcr cut ir)to type. Although hc could not ltave predicted

tlre ihte ol'this design, he certainll, appreciated the possibilitv of opposi-

tion to it. In the \\/auclroltc letter he wrote:

"ltt

the first place sclrolars and

paleograpiters will strongl)'object to the artcierlt and bear.rtihrl Arab tr'rit-

ing bcing tlrus coercecl ir)to wltat n'ill sc'ern to thenl a rvickedly rnecharri'

cai nrould.'f heir irrfluertce rvill alr'r'avs be to plonrote ils llear as possible

an e\act in-ritntiorr of the best fbrrns of calligr:rplrv."

Tr-r urrderstand Cill's prenronitiott. otte rtttlst appreciate the protoLrrtd

relatiorrship behveert Arabic calligraphv rncl Islanr. Arabic languaee and

script canie into plonrinence sinrttltarteotlsh'tlitlr the rise of Islarn as one

ol tlre rvorld s nlrjor religions. Becattse the Korrrr, tlre ho\' book of

lslanr, is regarded as tlre direct rvord ol Gocl as revealed to his proplret,

Muhanrnred, the calligraphi' in.rvhich it u'as vvritten has deep religious

significance: it is the rneans b)'rvhich Cod's n'ord i.s rnade nranit'est. Fur-

therrnore, Islarn does not allon' pictorirl represetltation of God or

Muhanrnred but relies on calligraphic preserttatiotts of the nanre oi God,

r\llalr, and the Prophet, Muharnnred. Thus, calligraphl' and the Arabic

script are inextricably associated u'itlr Islarn, and all matters affecting

them are judged by believers frorr a religious viel'point.

ir therefore is not surprising that most Arabic experts rllro tvere shorm

Gill's drau,ings disliked them. On October 30, 1932 Moustapha Ghozlan

Ber. the private calligrapher to the king of Eg'pt, rtrote,'Had I to correct

the specimen drafted by Mr. Gill, I would have to write it again altogeth-

er. . . .

'

Another letter reads,

"l

asked my Arabic calligraphist for a criti-

cism & he said the divisions are not ahrays in tlte correct places and the

letters haven't got the correct form, he says it shos's a lack of knorrledge

of the language and its script'"

Continuert on pagc 126

6rqor.y Gnuifs is grnphic striccs matngt.[or Crcalivc lVondrn, nn tducalionnl softwn

pultlishrr nwl dilisirn ol 7'ltr bnning Ctunpan.y' in Rcdmntl Ci4', CA.

Adir!.'n1qr

9

+Jq_o-

q-,O'-r0'.r_fr.a'6

z!

l_

,1. Rough pencil dram:.3s of Gill's

Arabic typeface revea. :ow he be;ar. to

get a feel for the unfa:-:ilar lette;

shapes Courtesy of t:.e Willran

Andrews Clark Libra:.' of UCLL

5. As Gill refrned the ::oeface. h:

extendeci the tails of s.ne itte:s a:d

shortened the desceriere on oti::s.

Courtesy of St. Bride ?rinting Li::a:y,

London.

7

in<jivrdual letters. Courtesy of the

William Andrews Clark Library of UCLF.

?. Final drawing of Gill s Arabic

rypeface,

sen: to 5ir Arthur Wauchooe, Brttrsh

High Commissioner in Palesiine in 1937.

Courtesy of the William Andrews Clark

Library of UCLA.

& Detail of Gills Arabic typeface.

Courtesy of the William Andrews Clark

Library of UCLA.

il?d

L^^Jl

JFJt

*y.a:p,i:

t*--ll LO.r-,

l,&+r*

J

..

,_)

..

EjdQ

t6

JL*-llt"

6. Glllcarefully drew h:s Anbic al::abet

on a sheet in pen and tnk. then cu: c:t

PRINTIll

'I

ot

generation of artists, writers, musi-

cians, and intellectuals. For such

scholars,

"renaissance"

is a word

defined by white culture only when

it chooses to take notice of black

influences that have existed all

along. Today, one can still sense the

evolution of the architects of the

Renaissance. The collective of

skilled visual artists left an abundant

body of work for the contempory

community to draw upon-a vast

visual language created at a time in

popular black culture when younger

artists were truh'steeped in the spir-

it and passion of the mornent.

Auilrcri Notc: Tfu

following

pcoplc

or institutions loaned or assislcd n,illt

reprcduclion of art

for

this arliclc.

Thanlu to !fu Archic Giycns Scnior Col-

lection oJ Afican Anrrican Literaturt

a! thc Univcrsih' of Minnaota. Min-

ncapolis; Schouburg Cenlcr.[or Blnck

Rcscarch, Tltc Nar York Pnliir Liltrary',

Ncrl York Cit1,: Paul Coalcs and tltr

Black Clnssic Prcss; Arl lilslitul( oJ

Chicago, lmaging and Rcproducliorrs

divisions; Thonas l4lirlh and lhc cstatt

of Nchard Brurc Nugcnt. Atlditional

lhanks nn dnc lo tht: E. Sinns Camp.

ltcll Collection. Boston Universitl' Li-

ltrary; Tuliza l:luning. Univcrsitl' oJ

Maryland: and A'klin Bwillcs, Tltc

Walker Collcction.

GiII Saails

Continuedfron pngc 111

These critics uere so closel'r'con-

nected to the calligraphic tradition

that they closed their minds to the

requirements of designing a gpe-

face. Referring ro Gill's dral'ing,

Moustapha Ghozlan Bey u'rote of

"a

new type of u'riting" ignoring any

distinction betrleen writing and

type. Given the need for the large

number of letter.s in Arabic, Gill

took liberties rr'itlr his design in an

effort to compensate for the limita-

tions of t)?ecasting. As he wrote,

Arabic "makes a different point of

view necessan,," but there was little

u,illingness by Arabs to adopt one.

Another reason this face was

126PRINT

never cut rvas the maelstrom of

events in Palestine. With the Balfour

;

Declaration in 1917, the British cre-

,

ated a dangerously contradictorl,

I

situation. The declaration effective.

i

ly gave

Jews

the right to establish a

homeland in the region, even as if

I

proclaimed the need not to preju-

, dice the rights of resident Arabs.

: Furthermore, a deep division exist-

: ed berween the British officials in

Palestine and politicians in London.

Whereas the politicians were moti-

vated by larger empirical interesls,

, British officials in Palestine daily

faced realities of the situation and

rvere often more sympathetic.

Sir Arthur Wauchope epitomized

,

the conciliatory nature of the British

officials in Palestine. ln Palcstint

Unfur lhc Mandntr, Albert Hyamson

tvrote of Wauchope that

"his

great

desire r^,as to grant eveDone's re

quest or to let him think that he in.

tended to do so. . . . In the end he

pleased and satisfied no one." In

fact, it is like\ that \{auchope com-

missioned the Arabic typeface sim-

p\, to shou'fairness and impartiali-

h,. While the

Jeu,s

had brouglrt to

Palestine their or.r,n steoographers,

q,pesetters, and printers, the Arabs

tr'ere less rlell-equipped. \4huchope

appeared to address this disparin'

b1, commissioning Gill's Arabic face,

but he could not be relied upon to

implement it.

In spring 1938, Wauchope left

office and a nerl High Commission-

er rvas named. Although tensions re-

mained high among all parties in

Palestine, the British had to concen-

I trate on the lvorsening situation in

Europe and could no longer pursue

cultural efforts such as this gpe de-

sign. Gill had long since received the

fee for his u'ork and used ir to bu)'

boat tickets home in 1937. Although

intercst in an Arabic typeface had

dissipated, he continued to cor'

respond r|ith those involved u'ith his

design untilApril 1938. He never did

ani'further work on it, horvever, and

bv October 1940 he rvas in the la.st

stage of lung cancer. \^Iith German

bombs falling near his home, Gill

died on November 17, 1940. In his

studio he left a typerlriter converted

to Arabic.

Autlnr\ Notc: Much of the rcscarch

for

lhis articlc-ittcluding thc reJer'

cnces to Eric Gill\ letttrs, diarics, and

thc conncnts by contcmporaries on

his Arabic tlpe-\'as donc at the

Wllian Anrlreu,s Clark Liltrary, an

of-canpus rnrc book liltrarl bslsnging

to the Univcrsitl,of California, Los An-

gelx. Thc othcr intportan! reference

natcrials u,crc Fiona .\[acCarthys bi-

ography, Eric Gill: .{ Lover's

Quest

for Art and God (1989), and Gills

Autobiography (J9Jd),

Arabic Typograpby

ConlinucdJron pagc il5

have skills in calligraphl,or at least

in drau,ing letterforms. Hence

toda1,'s absence of an alternative

basis that could constitute

'The

Neu' Arabic Typographi," is a verl'

serious problem.

To hclp rcsolvc thc problcns.facing

Arabic scrip!, Kltourt has developcd n

protolyn

for

a nat' printing alpltabct

tha! rvill bc introdttcui in hisforthcont-

ing book, Tlre Ultimate Script. /ts

chaplcrs, such as thosc on Arabic print-

ing hislory nnd dlclopntcnt. r'arious

languages in a conpara!ivc tlcsigrt

a n al1's i 5, o, 4 r r, ri ci s n; of con lc ntporn r

1'

typography. all rcvolvL around Khour.y's

ccntral call t0 sclarati calligraphic at-

t rib utcs

fro

nt A rab ic tt p efaces.

Thc prototl'pc, Khourt aplaincd. is

bascd on tlrc princililc qf disconncctcd

murc-casc lilterfornts. aild acts

(rs

a

gui dcl i n c

fo

r sh apu an d propo rti o n s

for

futurefont

dcsigrc. In thc books shot'-

case chapter, 55 difcrcnt sanples oJ

$,pcfaccs

arc prcsottcd and applied to a

walth aJ dcsign and 6 pographic rvorks,

opening net' approadt$ and design

motlcls in Arabic rathcr than con-

fronling

ilrc obstacles lhat

facc

Arobic

tl igi lizal i o n a n d progra m m i u g.

The Ultimate Scripr is schedulcd to

fu publislrcd in Ettglish and Arobic ncxl

lcnt

the Accideatd Art Direetor

Continued-from pagc 49

ouners of Barneys, thei'are of inter-

est to readers of service pieces, and

the department storei decline into

bankuptn' and an attempted sale

to a

Japanese

company was a quin-

tessential )ieu'York story about the

changing city. Neu,man stacked

type of decreasing size, as in a

tabloid body type layout, alongside

a photograph in which the brothers

seem to parodl'a couple of old-style

neighborhood haberdashers.

'l

ve

alrvays pushed for letting images

stand alone, as big as possible, with-

out puttins h'pe on them," Nervman

savs.

'Too

many art directors crop

too tighth'and put too much gpe

on."

After almost a year al Details,

Ner.r'man might seem read),to move

on. And he is moving on: to a ner.r'ac-

cent at the same magazine. He is

making a slow turn from the

"cool

jazz" influence to that of handlet-

tered morie posters from the 1960s,

as seen in a recent feature called

"\Vomen

on Top" and the

'Mondo

Hollyrvood" issue, both designed by

lohn Giordani.

"These

old movie stills are great,

if you crop them in an interesting

rr'a1,," he savs.

'And

they're free-

uhich is sreat for us. This isn't Dller-

toinnutt lli^c/li.1r "

He sounds not so

much like an art director \\'ith an eye

on the bud-qet as an old political

Protester Putting

one over on the

polrers that be. Which is hor{ he

likes to see himseli and his rlork, no

matter rlhat the magazine.

LogoRhythms

Continucd_tron pagc 39

themselves. he drarvs on the semi'

otic theorr of Charles Morris and

Charles Sanders Peirce. Mollerups

abiliq'ro fit so much source materi'

al into his schematic construct en-

ables him to incorporate a vast

number of iogos and marks into a

schema illustrating his theorv.

I find iittle to quarrel u'ith in the

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Long Draft of The Published Book.Dokumen382 halamanA Long Draft of The Published Book.Michael WolfersBelum ada peringkat

- Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture, 1855–1875Dari EverandPoetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture, 1855–1875Belum ada peringkat

- The English Church in the Eighteenth CenturyDari EverandThe English Church in the Eighteenth CenturyBelum ada peringkat

- The Future of Brexit Britain: Anglican Reflections on National Identity and European SolidarityDari EverandThe Future of Brexit Britain: Anglican Reflections on National Identity and European SolidarityBelum ada peringkat

- Early Illustrated Books A History of the Decoration and Illustration of Books in the 15th and 16th CenturiesDari EverandEarly Illustrated Books A History of the Decoration and Illustration of Books in the 15th and 16th CenturiesBelum ada peringkat

- Horizontal together: Art, dance, and queer embodiment in 1960s New YorkDari EverandHorizontal together: Art, dance, and queer embodiment in 1960s New YorkBelum ada peringkat

- The Darwinian Delusion: The Scientific Myth Of EvolutionismDari EverandThe Darwinian Delusion: The Scientific Myth Of EvolutionismBelum ada peringkat

- The Diary and Collected Letters of Madame D'Arblay, Frances Burney: Personal Memoirs & Recollections of Frances Burney, Including the Biography of the AuthorDari EverandThe Diary and Collected Letters of Madame D'Arblay, Frances Burney: Personal Memoirs & Recollections of Frances Burney, Including the Biography of the AuthorBelum ada peringkat

- The Poetry of Architecture: Or, the Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National CharacterDari EverandThe Poetry of Architecture: Or, the Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National CharacterBelum ada peringkat

- 14 Fun Facts About Ellis Island: A 15-Minute BookDari Everand14 Fun Facts About Ellis Island: A 15-Minute BookBelum ada peringkat

- I Lay This Body Down: The Transatlantic Life of Rosey E. PoolDari EverandI Lay This Body Down: The Transatlantic Life of Rosey E. PoolBelum ada peringkat

- Claes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgDokumen2 halamanClaes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgjovanaspikBelum ada peringkat

- Typography in Hope Mirrlees' ParisDokumen9 halamanTypography in Hope Mirrlees' ParisOindrilaBanerjeeBelum ada peringkat

- Sabbath's TheaterDokumen3 halamanSabbath's TheaterdearbhupiBelum ada peringkat

- Anti Modernism EssayDokumen3 halamanAnti Modernism EssayAndrew MunningsBelum ada peringkat

- Rudolf Schindler, Dr. T.P. MArtin HouseDokumen21 halamanRudolf Schindler, Dr. T.P. MArtin HousebsakhaeifarBelum ada peringkat

- Eero Saarinen Nlwxm7Dokumen14 halamanEero Saarinen Nlwxm7mariocapela86Belum ada peringkat

- The Ambassador's SecretDokumen2 halamanThe Ambassador's SecretPaulNNewmanBelum ada peringkat

- Art For Truth SakeDokumen16 halamanArt For Truth Sakehasnat basir100% (1)

- Proceedingscolle07wyom PDFDokumen284 halamanProceedingscolle07wyom PDFShishir Modak100% (1)

- Buy Study Guide Slaughterhouse Five RobertDokumen5 halamanBuy Study Guide Slaughterhouse Five RobertManuela Cristina ZotaBelum ada peringkat

- Margaret Mead - 'Changing Perspectives On Modernization' - Rethinking Modernization - Anthropological PerspectivesDokumen9 halamanMargaret Mead - 'Changing Perspectives On Modernization' - Rethinking Modernization - Anthropological Perspectivesgeneva1027Belum ada peringkat

- Frans HalsDokumen314 halamanFrans HalsGabriel Ríos100% (1)

- Edith Branson: Modern Woman, Modernist ArtistDokumen73 halamanEdith Branson: Modern Woman, Modernist ArtistPatricia Taylor Thompson100% (1)

- Michael Baxandall Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy - A Primer in The Social History of Pictorial Style 1988Dokumen97 halamanMichael Baxandall Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy - A Primer in The Social History of Pictorial Style 1988Fabiola HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Branden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFDokumen33 halamanBranden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFjpperBelum ada peringkat

- Raising The Flag of ModernismDokumen30 halamanRaising The Flag of ModernismJohn GreenBelum ada peringkat

- Fautrier PDFDokumen23 halamanFautrier PDFJonathan ArmentorBelum ada peringkat

- Expressions of Power: Queen Christina of Sweden and Patronage in Baroque EuropeDokumen455 halamanExpressions of Power: Queen Christina of Sweden and Patronage in Baroque EuropeMaria Fernanda López SantisoBelum ada peringkat

- Sander Cors Aug. 2.1Dokumen48 halamanSander Cors Aug. 2.1ivanhoe21530Belum ada peringkat

- Capability' Brown & The Landscapes of Middle EnglandDokumen17 halamanCapability' Brown & The Landscapes of Middle EnglandRogério PêgoBelum ada peringkat

- Bloom S Literary Places ST Peters BurgDokumen160 halamanBloom S Literary Places ST Peters BurgZahid Rafiq100% (1)

- Burgos Cathedral and Castillo TourDokumen9 halamanBurgos Cathedral and Castillo TourCostanza BeltramiBelum ada peringkat

- Federick Kiesler - CorrealismDokumen31 halamanFederick Kiesler - CorrealismTran Hoang ChanBelum ada peringkat

- Boulle eDokumen17 halamanBoulle eLucio100Belum ada peringkat

- E. On The Hot Seat - Mike Wallace Interviews Marcel DuchampDokumen21 halamanE. On The Hot Seat - Mike Wallace Interviews Marcel DuchampDavid LópezBelum ada peringkat

- IMP Buchloh On Ellsworth Kelly Matrix00ellsDokumen90 halamanIMP Buchloh On Ellsworth Kelly Matrix00ellstobyBelum ada peringkat

- Figurations of The Space Between: Sanford Budick and Wolfgang IserDokumen355 halamanFigurations of The Space Between: Sanford Budick and Wolfgang IserIvánTsarévich100% (1)

- TwomblyMomaBio 3Dokumen54 halamanTwomblyMomaBio 3Jonathan ArmentorBelum ada peringkat

- TypedesignerDokumen23 halamanTypedesignermalagirlfriend100% (4)

- Miriam Kammer, "Romanization, Rebellion and The Theatre of Ancient Palestine" (2010)Dokumen18 halamanMiriam Kammer, "Romanization, Rebellion and The Theatre of Ancient Palestine" (2010)JonathanBelum ada peringkat

- Riassunto Articoli GeoDokumen8 halamanRiassunto Articoli GeoDaniele LelliBelum ada peringkat

- American Impressionism and Realism The Painting of Modern Life 1885 1915Dokumen399 halamanAmerican Impressionism and Realism The Painting of Modern Life 1885 1915Cassandra Levasseur100% (1)

- MIT CHAPEL (Autosaved)Dokumen20 halamanMIT CHAPEL (Autosaved)hello helloBelum ada peringkat

- Caravaggio and ViolenceDokumen32 halamanCaravaggio and Violencezl88Belum ada peringkat

- Arthur A. ShurcliffDokumen27 halamanArthur A. ShurcliffHal ShurtleffBelum ada peringkat

- The Life and Leadership of Warren Gamaliel Bennis: Presented By: Junnifer T. ParaisoDokumen90 halamanThe Life and Leadership of Warren Gamaliel Bennis: Presented By: Junnifer T. ParaisoJunnifer ParaisoBelum ada peringkat

- Labor Relation Case DigestsDokumen48 halamanLabor Relation Case DigestsArahbellsBelum ada peringkat

- Enright Process Forgiveness 1Dokumen8 halamanEnright Process Forgiveness 1Michael Karako100% (1)

- Supernatural Shift Impartation For Married and SinglesDokumen1 halamanSupernatural Shift Impartation For Married and SinglesrefiloeBelum ada peringkat

- Singapore The CountryDokumen36 halamanSingapore The CountryAnanya SinhaBelum ada peringkat

- A God in The House - Poets Talk About Faith - Ilya KaminskyDokumen315 halamanA God in The House - Poets Talk About Faith - Ilya KaminskyArthur KayzakianBelum ada peringkat

- Mark of the Beast Decoded: King Solomon, Idolatry and the Hidden Meaning of 666Dokumen26 halamanMark of the Beast Decoded: King Solomon, Idolatry and the Hidden Meaning of 666Jonathan PhotiusBelum ada peringkat

- Death and Life After DeathDokumen16 halamanDeath and Life After DeathCarol KitakaBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On: Dr. Thomas L. ConstableDokumen53 halamanNotes On: Dr. Thomas L. ConstableTaylor QueenBelum ada peringkat

- Spiritual QuestDokumen313 halamanSpiritual Questmusic2850Belum ada peringkat

- English Lead Today Leader's GuideDokumen52 halamanEnglish Lead Today Leader's GuideEdwin Raj R100% (1)

- Nawabdin ElectricianDokumen3 halamanNawabdin Electriciansdjaf afhskj56% (9)

- Samuel L. Brengle, The Salvation Army - The Way of Holiness-The Salvation Army (1920) PDFDokumen35 halamanSamuel L. Brengle, The Salvation Army - The Way of Holiness-The Salvation Army (1920) PDFFidenceBelum ada peringkat

- A Study of The Traditional Manipuri Costumes & The Influence OD Hallyu Culture To Develop A Range of Contemorary Garments PDFDokumen66 halamanA Study of The Traditional Manipuri Costumes & The Influence OD Hallyu Culture To Develop A Range of Contemorary Garments PDFSadiqul Azad SouravBelum ada peringkat

- Structure of Hand Gestures in Indian DancingDokumen1 halamanStructure of Hand Gestures in Indian DancingAndré-Luiz TecelãoBelum ada peringkat

- Kalki The Next Avatar of God PDFDokumen8 halamanKalki The Next Avatar of God PDFmegakiran100% (1)

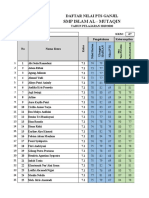

- NILAI PPKN VII Dan VIII MID GANJIL 2019-2020Dokumen37 halamanNILAI PPKN VII Dan VIII MID GANJIL 2019-2020Dheden TrmBelum ada peringkat

- Practice Exercises BNTGDokumen61 halamanPractice Exercises BNTGArvin GBelum ada peringkat

- Color Politics of DesignDokumen3 halamanColor Politics of DesigntanyoBelum ada peringkat

- In 1947 A Corps of Architects and Engineers Were Tasked To Study The Modern US and Latin American Capitals and Formulate A Master Plan For ManilaDokumen7 halamanIn 1947 A Corps of Architects and Engineers Were Tasked To Study The Modern US and Latin American Capitals and Formulate A Master Plan For ManilaEliza Mae AquinoBelum ada peringkat

- " Wendy - B. Howard.: Despatch Magazine Vol. 26:1 Nov., 2014Dokumen100 halaman" Wendy - B. Howard.: Despatch Magazine Vol. 26:1 Nov., 2014sterhowardBelum ada peringkat

- Akshara Mana Malai - A Garland of Letters for ArunachalaDokumen18 halamanAkshara Mana Malai - A Garland of Letters for ArunachalaVishalSelvanBelum ada peringkat

- Causes of Suicidal ThoughtsDokumen10 halamanCauses of Suicidal ThoughtsSarah Saleem100% (1)

- The Precession of The Equinoxes.Dokumen4 halamanThe Precession of The Equinoxes.Leandros CorieltauvorumBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Scout ProgramDokumen3 halamanSample Scout ProgramRomeda Valera100% (1)

- The rise and consolidation of the Fulani Empire in HausalandDokumen295 halamanThe rise and consolidation of the Fulani Empire in HausalandUmar Muhammad80% (5)

- Neopythagoreans at The Porta Maggiore in Rome, Spencer.Dokumen9 halamanNeopythagoreans at The Porta Maggiore in Rome, Spencer.sicarri100% (1)

- Definition and Meaning of SeerahDokumen12 halamanDefinition and Meaning of SeerahHafiz Bilal Naseem Shah100% (1)

- Revolution by Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him)Dokumen1 halamanRevolution by Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him)The Holy IslamBelum ada peringkat

- Bible Atlas Manual PDFDokumen168 halamanBible Atlas Manual PDFCitac_1100% (1)