Ptolemaic Soldiers Under The Romans

Diunggah oleh

bucellarii0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

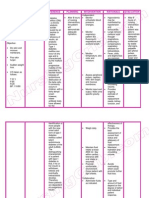

29 tayangan6 halamanZeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 94 (1992) 213–216

Dr. Rudolf Habelt

Judul Asli

PTOLEMAIC SOLDIERS UNDER THE ROMANS

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniZeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 94 (1992) 213–216

Dr. Rudolf Habelt

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

29 tayangan6 halamanPtolemaic Soldiers Under The Romans

Diunggah oleh

bucellariiZeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 94 (1992) 213–216

Dr. Rudolf Habelt

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 6

ADAM AJTAR

PTOLEMAI C SOLDI ERS UNDER THE ROMANS

A NOTE ON THE DEDI CATI ON OF AN I LARCHES ( ZPE 87, 1991, 5355)

aus: Zeitschrift fr Papyrologie und Epigraphik 94 (1992) 213216

Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn

213

PTOLEMAIC SOLDIERS UNDER THE ROMANS

A NOTE ON THE DEDICATION OF AN ILARCHES (ZPE 87, 1991, 53-55)

*

The following inscription from the collection of GraecoRoman Museum in Alexandria has

been published by E. Bernand in ZPE 87

1

.

Ippvn ntop`-

vn: Svsignhw

lrxhw: Ddumo-

w prostatn -

pohsen, (touw) ib

Kasarow, Pa-

xn *a vac.

pgay

The inscription is dated April 27th, 18 B.C.

According to E. Bernand this is a dedication made by indigenous cavalrymen remaining under

the command of a certain Sosigenes. The person actually responsible for the execution of the

dedication was Didymos, prostates. Most probably he was an administrator of a temple who while

making the dedication acted to the order of the commander of a by-passing military unit. For E.

Bernand the date of the dedication is decisive to connect it with the Roman army.

I disagree with the interpretation of the inscription proposed by E. Bernand. My first and most

important objection concerns his regarding of this text as being a testimony for the Roman military

activity in recently conquered Egypt. In my opinion, in spite of the Augustean date of the

dedication its authors ppew ntpioi were not Roman soldiers. The term lrxhw, characteristic

of Hellenistic cavalry officers

2

and here used to denote the commander of the ppew clearly

indicates that they were descendants of the Ptolemaic army. As was proven recently by E. Van' t

Dack in contrast to earlier opinions

3

, the number of troops in the command of the last Ptolemies

was rather considerable. At the moment of Cesar's intervention in Egypt these included 20 000 of

infantry and 2 000 of cavalry

4

. We have very scanty information as for what happened to those

*

I would like to thank H. E. Stiene for correction of my English.

1

E. Bernand, Ddicace d'un ilarque (18 av. J.C.), ZPE 87, 1991, pp 53-55. The inscription is of unknown

provenance. The note "envoi de la Direction Gnerale en 1913" present in the inventory of the GraecoRoman

Museum in Alexandria may suggest that it does not come from Alexandria or its vicinity.

2

If Polybius (6, 25, 1-2) understood elh in the sense of Latin turma and saw a Roman decurion in Greek

ilarches, this does not mean that the term ilarches was ever in the real use to denote Roman cavalry officer. In

Polybius day, the Greek terminology for Roman institutions was still nonexistent and it is normal then that he

described Roman army in terms borrowed from armies of Heilenistic kingdoms contemporary to him.

3

E. Van't Dack L' arme lagide de 55 30 av. J. C., JJP XIX, 1983, pp. 7786.

4

These are numbers given by Julius Caesar in De bello civili III 110, 16 and De bello Alexandrino 2, 14,

here quoted after E. Van't Dack, op.cit.

214 Adam ajtar

people after the Romans conquered the country. No doubt some of them, for example specialists in

different kinds of military art, may have been incorporated into the Roman army by force; others,

especially those for whom the Ptolemaic army was only an episode in their life, may have joined

the Romans voluntarily. Most probably, those people quickly underwent romanization and are

hardly distinguishable in our sources. The situation was quite different with those from among the

former Ptolemaic soldiers who through their military service became closely tied with the country

and its life. This concerns military settlers in the first line. It is exactly from this milieu that we

have two documents very significant for understanding the ilarches dedication.

A papyrus found in Tebtunis but drawn in Ptolemais Euergetis, dated probably to 20/19 B.C.,

is a contract between two brothers, Herakles son of Akousilaos (the elder brother) and Akousilaos

son of Akousilaos, concerning the partition of land inherited from their father

5

. In the promise on

oath to keep some engagements which follows the contract proper, the elder brother styles himself

in a well Ptolemaic manner, ll. 1718: Hraklw Akousilou Ma[ke]dn tn katok[v(n)

ppv(n)]

6

. In the same papyrus, below the contract and Herakles' promise, another document is

contained, "an official notice of a cession of cleruchic land to another Acusilaus, which has no

apparent connection with the preceding matter"

7

. The person who cedes the land is a certain

Kstvr Apollvnou Ammvniew pprxhw pndrn tw a pparxeaw tn

(gdohkont)arorvn

8

A similar situation is in P.Oxy II 277 (19/18 B.C.). Di onsi ow

Al[e]jndrou Makedn pprxhw pndrn

9

cedes his land near the village of Pamis to

Artemdvrow Artemidrou Makedn

10

who is pprxhw pndrn too. Obviously in all

three cases the active service of the people mentioned is out of question

11

. It is worth of stressing,

however, that ten years after the fall of the Ptolemies they still use their Ptolemaic military titles and

in the Ptolemaic manner underline with pride their Greek origin. Probably, they also preserve a

kind of social solidarity, as the ties between Dionysios son of Alexandros and Artemidoros son of

Artemidoros from P.Oxy 277 may prove. Of particular interest for us is P.Tebt II 382 in which

Herakles son of Akousilaos calls himself Makedn tn katokvn ppvn. Originally, these

ktoikoi ppew must have been Ptolemaic military settlers obliged to serve in cavalry. If in 20/19

B.C. one of those ppew underlines his belonging to this group, this is probably because they still

constitute a socio-ethnic reality.

One should note in this place that E. Bernand is most probably mistaken when he understands

the term ntpioi from the ilarches dedication as "indigenous". Though in some cases the adjective

in question may have the meaning indigenous

12

, in my opinion, however, this meaning cannot be

applied with reference to the inscription discussed here, for indigenous people involved in the

5

PTebt II 382; the contract is dated generally by kasarow krthsiw; for its possible dating to 20/19, cf. F.

Zucker, RIDA 8, 1964, p. 164.

6

For the person, cf. PP II 2648, IV 9285.

7

PTebt II 382, p. 229.

8

Cf. PP II 2218, IV 9342, VIII 2218add.

9

Cf. PP VIII 2202b.

10

The person in PP VIII 2194a.

11

Cf. E. Van't Dack, op.cit., p. 84.

12

The classical example registered both in Preisigke's Worterbuch and in Liddell-Scott-Jones, s.vv., is PLond

2 192, 94 (1st cent. A.D.), in which ntpioi (in Fayum) are opposed to Alejandrew.

Ptolemaic Soldiers under the Romans 215

military service of the Ptolemies were always called gxrioi

13

. To my mind the term ntpioi

should be understood literally here: ppew ntpioi were cavalrymen of no matter what origin but

living in the same tpow. This might have been a village, a town or even a wider territory in the

meaning of the term close or identical with toparxa

14

.

My second objection relates to the interpretation given by E. Bemand to the term prostthw

and the role played by this man in accomplishing the dedication. E. Bernand rightly points out that

the term prostates in the period under review had generally two meanings: (1) president of an

association both cultic and professional (2) administrator of a temple, and considers the second of the

two meanings to be the right one in the inscription in question. In Greek and Demotic

documents from Egypt, both in inscriptions and in papyri, when prostates of (a temple) of a certain

god is meant, then such a person is always described in the words prostthw + genitive of the

god's name

15

. Meanwhile, this is not our case and there is no doubt that only the first meaning of

the two, president of an association, may be applied with reference to the text discussed here.

The association of which Didymos was the prostates at the moment of accomplishing the

dedication can only be the association of ppew ntpioi. The existence of different kind of

soldiers' associations is well attested for Hellenistic period. The phenomenon has been studied in

detail by M. Launay

16

and there are no need to repeat all his findings. Here I would like to confine

myself to Late Ptolemaic Egypt and to cite several examples of soldiers' associations significant for

understanding the ilarches inscription. These associations are known mainly through various dedi-

cations they made. During the reign of Ptolemy XII Auletes o tetagmnon xontew n t

Arsinothi ppew dedicated for that king and his wife Cleopatra Tryphaina as is commemorated

by the inscription originated from Arsinoe-Crocodilopolis

17

. These ppew had their rxisuna-

gvgw being at the same time rxierew (name not preserved) and this fact clearly indicates that

they formed an association (sunagvg most probably). Another dedication from Fayum dated to

the eleventh year of a King (most probably from the 1st cent B.C.) mentions a certain Nicolaos

erew and the rxiprostthw Sosandros, Aetolian, who is described also as ilarches and

hipparches

18

. This allows us to imagine a soldiers' association in which the main role of rxi-

prostthw was played for a certain period by the commander of a tactical unit. In an inscription

on a statue base, also from Fayum, there appears a somewhat mysterious [ snodow tn

(prtvn) flvn k]a x(ili)(rxvn) ka per tow [basilaw maxairof]` rvn rmh'

19

.

This synodos had its prostates (name not preserved) and hiereus Herakleitos. Most probably, the

13

Cf. for example Fl. Josephus, AntiquiL jud. XIII, 337 (description of the army of Ptolemy IX Soter II in war

against Judea): sunyroise ... per pnte muridaw tn gxvrvn, w dnioi suggrafew erkasin, kt.

14

For various meanings of the term tpow, cf references in Preisigke's Wrterbuch, s.v.

15

Demotic counterpart is rd- "agent of the god". About prostates as a temple officiaL see generally W. Otto,

Priester und Tempel im hellenistischen gypten I, Leipzig und Berlin 1905, pp. 361-363. To the examples of

prosttai to yeo cited by E. Bernand, op.cit., p. 54, note 10, Psenamunis, son of Pekysis, prophet of Isis and

prostthw to yeo may be added. He is known from several Greek and two Demotic ostraca from the region

Thebes-Hermonthis, dated to Early Roman period; for his dossier, see W. Otto, op.cit. I, pp. 359-363.

16

M. Launey, Recherches sur les armes hellenistiques II, Paris 1950, pp. 1001-1036.

17

SB I 623 (=IFayoum I 9)

18

SB I 626 (=IFayourn I 16)

19

SB I 624 (=IFayoum I 17); the reading of the association's name is that of E. Bemand in IFayoum, loc.cit.

216 Adam ajtar

same unit appears in BGU IV 1190, a papyrus from mummy cartonnage from Abusir el-Meleq:

snodow rmg t` n` ` s` f` a` ln ka (xilirxvn)

20

ka per tow basilew (sic!) maxairo-

frvn. Here, two officials of the association, prostates Dorion and grammateus Dionysios,

address Antiochos, grammatew tn dunmevn, regarding the munitions. A very interesting

example of a military association is to be found in two inscriptions from Hermopolis in which o

parafedreontew n Ermo plei jnoi Apollvnitai ka o sunpoliteumenoi ktstai

are mentioned

21

. M. Launey gives the following description of this union

22

: "... en mme temps

que cultuelle, cette association est quasi-ethnique; ... D'un autre ct, l'association garde quelque

chose de son organisation militaire: les noms sont classs en six hgmonies, avec les officiers en

tte de chacune d'elles. Mais il suffit de compter les noms pour constater qu'il s'en font de bou-

coup que tous les garnisaires d'Hermopolis fassant partie de l'association; de plus, les dignitaires

de l'association ne sont pas les officiers. Il y a l une curieuse jusxtaposition de deux hierarchie

distincte l'une valable dans l'ordre militaire, l'autre dans le cadre de l'association cultuelle".

Launey's characteristic of the association of o parafedreontew n Ermo plei jnoi

Apollvnitai ka sunpoliteumenoi ktstai is also valid for the association of ppew

ntpioi. Thus, on the grounds of the material discussed above, the full context of the ilarches

inscription may be described as follows:

This inscription commemorates a dedication made by the former Ptolemaic cavalrymen.

Originally they belonged to the same lh under the command of a certain Sosigenes and as military

settlers they lived in the same place. They also formed an association the character of which

appears to have been mainly cultic but which must have had some traits of the professional

soldiers' corporation too. After 30 B.C. an active service of those peoples ended but still having

their homes near each other they continued their social life organised along the lines of by-gone

times with institutions and behaviours proper to them. They still preserved, at least in terminology,

some traits of their military organization and this is visible e.g when they call, as they did before,

Sosigenes their ilarches. What has really survived from their life prior to 30 B.C. is their

association

23

though this surely changed its character; in 18 B.C. it could not have been a

professional corporation any more but only a social recollective club. The association had the

prostates at its head, which post appears to have been open to all association members; here it is

hold by certain Didymos and not by the former commander of the tactical unit - Sosigenes. As a

prostates Didymos was responsible for the common religious and social performances of the

association members and it is absolutely intelligible that he overviewed the accomplishing of the

dedication.

Warsaw-Cologne Adam ajtar

20

E. Bernand's reading (IFayoum I, p. 54) instead of xiliodrxmvn proposed in BGU IV 1190.

21

SB I 4206 (stele J), SB V 8006 (stele R); cf. also PGiss 99.

22

M. Launey, op.cit., p. 1025.

23

One should note in this place the difference in calling the commander of ppew and the president of their

association. Sosigenes is generally described as ilarches, without defining precisely the time, while Didymos was

prostates in this very time of dedication, what is indicated by the participle of the present active.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Nursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1Dokumen2 halamanNursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1deric85% (46)

- Crowd Management - Model Course128Dokumen117 halamanCrowd Management - Model Course128alonso_r100% (4)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Ptolemaic Annexation of Lycia SEG 27.929Dokumen18 halamanThe Ptolemaic Annexation of Lycia SEG 27.929bucellariiBelum ada peringkat

- The Roman Conquest of DalmatiaDokumen26 halamanThe Roman Conquest of DalmatiabucellariiBelum ada peringkat

- Rustoiu 2011 Eastern CeltsDokumen39 halamanRustoiu 2011 Eastern Celtsbucellarii100% (1)

- The Romanization of The Greek Elite in AchaiaDokumen33 halamanThe Romanization of The Greek Elite in AchaiabucellariiBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 1 My Hobbies Lesson 1 Getting StartedDokumen14 halamanUnit 1 My Hobbies Lesson 1 Getting StartedhienBelum ada peringkat

- Ap Reg W# 5-Scaffold For Transfer TemplateDokumen2 halamanAp Reg W# 5-Scaffold For Transfer TemplateJunafel Boiser Garcia100% (2)

- Removal of Chloride in The Kraft Chemical Recovery CycleDokumen8 halamanRemoval of Chloride in The Kraft Chemical Recovery CycleVeldaa AmiraaBelum ada peringkat

- The Mathematics Behind ContagionDokumen6 halamanThe Mathematics Behind Contagionkoonertex50% (2)

- Linic - by SlidesgoDokumen84 halamanLinic - by SlidesgoKhansa MutiaraHasnaBelum ada peringkat

- C779-C779M - 12 Standard Test Method For Abrasion of Horizontal Concrete SurfacesDokumen7 halamanC779-C779M - 12 Standard Test Method For Abrasion of Horizontal Concrete SurfacesFahad RedaBelum ada peringkat

- Syncretism and SeparationDokumen15 halamanSyncretism and SeparationdairingprincessBelum ada peringkat

- Diploma Thesis-P AdamecDokumen82 halamanDiploma Thesis-P AdamecKristine Guia CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- Adobe Scan 23-Feb-2024Dokumen4 halamanAdobe Scan 23-Feb-2024muzwalimub4104Belum ada peringkat

- Maxdb Backup RecoveryDokumen44 halamanMaxdb Backup Recoveryft1ft1Belum ada peringkat

- Vallen AE AccesoriesDokumen11 halamanVallen AE AccesoriesSebastian RozoBelum ada peringkat

- Operating Instructions: Vacuum Drying Oven Pump ModuleDokumen56 halamanOperating Instructions: Vacuum Drying Oven Pump ModuleSarah NeoSkyrerBelum ada peringkat

- Canadian Solar-Datasheet-All-Black CS6K-MS v5.57 ENDokumen2 halamanCanadian Solar-Datasheet-All-Black CS6K-MS v5.57 ENParamesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- 100 IELTS Essay Topics For IELTS Writing - My IELTS Classroom BlogDokumen16 halaman100 IELTS Essay Topics For IELTS Writing - My IELTS Classroom BlogtestBelum ada peringkat

- Power Systems (K-Wiki - CH 4 - Stability)Dokumen32 halamanPower Systems (K-Wiki - CH 4 - Stability)Priyanshu GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Sequence Analytical and Vector Geometry at Teaching of Solid Geometry at Secondary SchoolDokumen10 halamanSequence Analytical and Vector Geometry at Teaching of Solid Geometry at Secondary SchoolJuan S. PalmaBelum ada peringkat

- A Review of Automatic License Plate Recognition System in Mobile-Based PlatformDokumen6 halamanA Review of Automatic License Plate Recognition System in Mobile-Based PlatformadiaBelum ada peringkat

- Physics Cheat SheetDokumen8 halamanPhysics Cheat SheetJeremiah MoussaBelum ada peringkat

- Demystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggDokumen6 halamanDemystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggEddie CaptainBelum ada peringkat

- Note 15-Feb-2023Dokumen4 halamanNote 15-Feb-2023Oliver ScissorsBelum ada peringkat

- Free DMAIC Checklist Template Excel DownloadDokumen5 halamanFree DMAIC Checklist Template Excel DownloadErik Leonel LucianoBelum ada peringkat

- Algorithm Design TechniquesDokumen24 halamanAlgorithm Design TechniquespermasaBelum ada peringkat

- MODULE-6 Human Person As Embodied SpiritDokumen18 halamanMODULE-6 Human Person As Embodied SpiritRoyceBelum ada peringkat

- ICCM2014Dokumen28 halamanICCM2014chenlei07Belum ada peringkat

- Pay Scale WorkshopDokumen5 halamanPay Scale WorkshopIbraBelum ada peringkat

- MC-8002 Mixer 2Dokumen1 halamanMC-8002 Mixer 2JAIDEV KUMAR RANIBelum ada peringkat

- Useful C Library FunctionDokumen31 halamanUseful C Library FunctionraviBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Farmasi Klinis: Feby Purnama Sari 1802036Dokumen9 halamanTugas Farmasi Klinis: Feby Purnama Sari 1802036Feby Purnama SariBelum ada peringkat