A Matter of Martyrs

Diunggah oleh

tahreeq0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

19 tayangan2 halamanChamanlal Article in The hindu

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

TXT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniChamanlal Article in The hindu

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai TXT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

19 tayangan2 halamanA Matter of Martyrs

Diunggah oleh

tahreeqChamanlal Article in The hindu

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai TXT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 2

July 31-August 1, 1857. It was the day of Bakrid (Id-ul-Fitr).

Two hundred and e

ighty-two sepoys of the Indian army, who rebelled against the British colonial o

ccupation of India, were massacred and dumped into a dry well 100 yards from the

Ajnala police station in Amritsar district. The remains were dug out recently b

y the town people themselves, without any governmental help. At the time of this

article going to press, the cremation was scheduled to take place on August 1.

The Punjab Government has allotted a plot of land for the cremation, and a memor

ial will be built on it later.

Two accounts are available about the Ajnala incident. One was the colonial versi

on of Frederic Cooper, the then Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar district, whose

book The Crisis in the Punjab from the 10th of May Until the Fall of Delhi was p

ublished in 1858 from London. The other, published in the 1920s, was a nationali

st version, by Giani Hira Singh Dard, a respected Punjabi writer, historian and

editor of the Punjabi magazine Phulwari from Amritsar. His version was carried w

ith photographs in the November 1928 Fansi Ank (Execution Issue) from Allahabad,

and it was later included in the nationalist historian and editor Pt. Sunder La

ls proscribed book Bharat Mein Angrezi Raj (British Rule in India). Giani Hira Si

ngh Dard had recorded the eyewitness account of Baba Jagat Singh, who was nearly

95 in 1928 and was in his twenties at the time of the massacre.

Rebellion broke out in Meerut on May 10, 21 days ahead of the decided date. As p

er Coopers account, thousands of Poorbeah sepoys of the 26th Regiment of Bengal N

ative Infantry were disarmed in Lahores Meean Meer Cant. The rebellion spread in

different regions of Punjab, which Cooper spelled as Lahore, Umritsur, Phillour,

Jhelum, Sealkote, Jullundur, Ferozepore, Sirsa, Hote Mardan, Peshawur and Loodh

ianah . On July 30, nearly 500 disarmed sepoys rebelled near Ajnala. One of them

Prakash Singh, alias Prakash Pandey killed Major Spencer with the Majors own swo

rd, and they all fled south, only to be trapped near Ajnala, by Tehsildar Dewan

Pran Naths agents, who alerted the district administration. Armed forces arrived

and rained bullets. Many people jumped into the river near the village of Daddia

n and drowned. Others were taken to the Ajnala police station to be hanged, whil

e some were forced into a dungeon. Deputy Commissioner Cooper had ordered a long

rope. The rebels were to be killed on the night of July 31. Due to rain, the ex

ecution was postponed until the next morning.

On August 1, 237 rebel sepoys were taken out to an open ground in front of the p

olice station and killed in turns of 10. When those in the dungeon did not show

up, it was found that 45 of them had suffocated to death. The 282 bodies were th

rown into a dry well, 100 yards from the police station. The well was filled wit

h sand. Cooper called it rebels grave and wanted that written in Persian, Gurmukhi

and English. At two places in his book, he compares this well to Holwells Black H

ole of Calcutta of 1756 and the well of Cawnpore of 1857, where rebels dumped th

e bodies of British officials. Coopers glee on attaining revenge is evident. There

is a well at Cawnpore, but there is also one at Ajnala! The well was in place ti

ll 1972, inscribed with the words Kalian Wala Khuh (The Well of Blacks).

In 1928, it looked like a raised sand hill. In 1957, the centenary celebrations

of 1857 were observed here in the presence of the then Chief Minister Pratap Sin

gh Kairon. However, in 1972, villagers built a room over the well and turned it

into a Gurdwara. In 2007, the 150th anniversary of the 1857 killings was observe

d at the site.

In 2012, the town people formed an 11-member committee of all practising Sikhs,

led by trade unionist Amarjit Singh Sarkaria, to honour the martyrs by disinterr

ing their remains from the well. They built a new Gurdwara nearby and began digg

ing of the well on February 28, 2014. Before beginning the work, they tried thei

r best to involve the State and Central Governments, but their efforts were futi

le as no agency, including the Archaeological Survey of India showed interest. W

ithin three days of digging, nearly hundred human skulls, teeth and bones were e

xhumed. Hundreds of volunteers took part in the digging and thousands gathered t

o watch. Medals, jewellery and coins were also retrieved.

Officials from the administration and the Archaeology department turned up to co

llect the remains for DNA testing.

The managing committee renamed Kalian Wala Khuh as Shaheedan Wala Khuh (Martyrs W

ell) and appealed to the Governments of Punjab and India to give them the vacant

land nearby, under the control of the army, for the cremation.

Chaman Lal, retired Professor from JNU, New Delhi, is presently Professor-Coordi

nator of Centre for Comparative Literature at Central University of Punjab, Bath

inda, and author of Understanding Bhagat Singh.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Ambedkar PosterDokumen1 halamanAmbedkar PostertahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- Walter Benjamin What Is Epic TheaterDokumen4 halamanWalter Benjamin What Is Epic TheatertahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- TeltumbdeDokumen106 halamanTeltumbdetahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- Prem ChandDokumen1 halamanPrem ChandtahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- VallejoDokumen14 halamanVallejotahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- What Is MaoismDokumen22 halamanWhat Is MaoismtahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- Lakshman GayakwadDokumen7 halamanLakshman GayakwadtahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- What Is MaoismDokumen10 halamanWhat Is MaoismtahreeqBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- SAI Fruto, Jose Adenor M M O-137794 PAF: Gross Pay: 91.260.71Dokumen1 halamanSAI Fruto, Jose Adenor M M O-137794 PAF: Gross Pay: 91.260.71bktsuna0201Belum ada peringkat

- Blades in The Dark: Bravos PlaybookDokumen1 halamanBlades in The Dark: Bravos PlaybooktheoldwisemanBelum ada peringkat

- St1 Reading Mintafeladat - OriginalDokumen12 halamanSt1 Reading Mintafeladat - OriginalEmberBelum ada peringkat

- Full Thrust X DimensionsDokumen123 halamanFull Thrust X DimensionsRolfSchollaert100% (2)

- 40K FAQ Black TemplarsDokumen1 halaman40K FAQ Black TemplarselmenathryllBelum ada peringkat

- Database Qoo10Dokumen76 halamanDatabase Qoo10Anonymous gnnzIEfSKu100% (1)

- Rizal's Life Exile Trial and DeathDokumen9 halamanRizal's Life Exile Trial and Deatherickson hernanBelum ada peringkat

- 1058 - SURYA ENTERPRISE (Naharlagun)Dokumen34 halaman1058 - SURYA ENTERPRISE (Naharlagun)bijit14603Belum ada peringkat

- Activity Tema 4 SM 4º PRIMARIADokumen10 halamanActivity Tema 4 SM 4º PRIMARIAAdriana CanedoBelum ada peringkat

- Dod STD 2168Dokumen14 halamanDod STD 2168xray1oneBelum ada peringkat

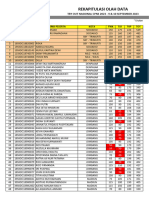

- Rekap To NasionalDokumen52 halamanRekap To NasionalMelisawiBelum ada peringkat

- German Type VII SubmarineDokumen10 halamanGerman Type VII SubmarineOliverChrisLudwigBelum ada peringkat

- 4 The U S Battlefront and Homefront in Wwi 1Dokumen2 halaman4 The U S Battlefront and Homefront in Wwi 1api-301854263Belum ada peringkat

- The Ottoman Coinage of Tilimsan / Michael L. BatesDokumen15 halamanThe Ottoman Coinage of Tilimsan / Michael L. BatesDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Geneva Convention BriefDokumen4 halamanGeneva Convention BriefVivekananda Swaroop0% (1)

- Naruto Shippuden - Episode ListDokumen2 halamanNaruto Shippuden - Episode Listyeabtsega Tesfaye0% (1)

- SAAMI Z299.4 Centerfire Rifle Approved 12-14-2015Dokumen375 halamanSAAMI Z299.4 Centerfire Rifle Approved 12-14-2015Dario Likes SurfingBelum ada peringkat

- Luxembourg Under Fire (Excerpt)Dokumen1 halamanLuxembourg Under Fire (Excerpt)Fausto GardiniBelum ada peringkat

- BlazeMasterEternalWar2011 2013Dokumen154 halamanBlazeMasterEternalWar2011 2013Stanisław GiersBelum ada peringkat

- Ffifro: Fewtsrl O!/o!/toiiDokumen25 halamanFfifro: Fewtsrl O!/o!/toiiROHINIBelum ada peringkat

- 8yale Hemingway, Fitzgerald, FaulknerDokumen256 halaman8yale Hemingway, Fitzgerald, FaulknerSpiru HaretBelum ada peringkat

- Military - Brother Jonathan - New YorkDokumen204 halamanMilitary - Brother Jonathan - New YorkThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (4)

- Ocampo 807 Scra 223Dokumen1 halamanOcampo 807 Scra 223Helen Grace M. BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- GPS Seminar SynopsisDokumen67 halamanGPS Seminar SynopsisAnkur Paul100% (3)

- The Clash - Career OpportunitiesDokumen1 halamanThe Clash - Career OpportunitiesEC Pisano RiggioBelum ada peringkat

- Kwangju Massacre and Its Effects On Korean Society and PoliticsDokumen8 halamanKwangju Massacre and Its Effects On Korean Society and PoliticsNaobi IrenBelum ada peringkat

- Metal Gearing Box Gun QuotationsDokumen56 halamanMetal Gearing Box Gun QuotationsFery MulyanaBelum ada peringkat

- Hex Bolts DIN 931 and Screws DIN 933Dokumen13 halamanHex Bolts DIN 931 and Screws DIN 933Azra HumićBelum ada peringkat

- Erich Von Manstein Lost Victories PDFDokumen2 halamanErich Von Manstein Lost Victories PDFMarla0% (2)

- HIV Prirucnik Za Lekare PDFDokumen240 halamanHIV Prirucnik Za Lekare PDFpostexisterBelum ada peringkat