Beyond Green Jobs Excerpt Workforce Development and Apprenticeship PDF

Diunggah oleh

mailmaverick8167Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Beyond Green Jobs Excerpt Workforce Development and Apprenticeship PDF

Diunggah oleh

mailmaverick8167Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Workforce Development &

Apprenticeship

Construction contractors generally lack the resources

or incentives to invest in comprehensive worker

training on their own. Given the transient nature of

employment in the industry, individual employers face

the possibility that investing in training for current

employees might benet their competitors in the future

when their current employees go to work elsewhere.

But another pathway to training does exist. Through

the collective bargaining process, employers agree

to invest in joint labor-management administered

apprenticeship programs that oer intensive skills

training. This apprenticeship system represents the most

eective construction training mechanism in the United

States, with 15,000 certied instructors, 1,500 state-of-

the-art training facilities, and hundreds of millions of

dollars of private capital.

18

The investment also pays o

over the career of the individual participant, as these

training programs include career skill enhancement

opportunities after apprenticeship. Employers benet

from an established workforce development system

that ensures quality production and work output, while

workers can count on the most advanced training

available. Table 4 shows that employer contributions,

including in basic hourly wages, benets, and training

that all add up to the prevailing wage rate.

About 70% of apprenticeship programs are joint

labor-management ventures. This means that workers

(unions) and employers (management) jointly design

the apprenticeship training curriculum and processes.

19

In California, 82%, of registered apprenticeship

programs are joint labor-management apprenticeships,

but these programs produce about 92% of the states

registered apprenticeship graduates.

20

As determined by

local collective bargaining agreements, a few cents for

every hour that a worker works goes toward a fund to

train apprentices and to provide ongoing skill-building

trainings for journey-level workers. Because these

apprenticeship programs collect their workforce

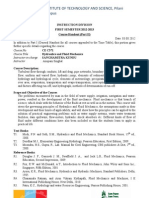

Table 3

Table 4

Source: California Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Apprenticeship Standards, Public Works Apprentice Wage Sheets.

Wage levels increase as apprentices advance in their training. Wage levels vary by craft. Graphic Modied From: Construction Apprenticeship

Programs: Career Training for Californias Recovery, by Corinne Wilson, Center on Policy Initiatives, 2009.

Total hourly wages include health, pension and training dollars, which create a healthy, well-trained workforce over time. Q1 2009.

Source: California Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Apprenticeship Standards, Public Works Apprentice Wage Sheets.

Graphic Modied From: Construction Apprenticeship Programs: Career Training for Californias Recovery, by Corinne Wilson, Center on Policy

Initiatives, 2009. **Los Angeles and Orange counties

Apprenticeship Basic Hourly Wage Increase Schedule, San Diego County, California, Q1 2009*

Wage increases dependent upon successful completion of training segments

Years in Program Part of year (1/2) Electrician, Inside Wireman Plumber, Pipetter, Steamtter

Wage level per 800 on-the-job training hours Wage level per 1,600 on-the-job training hours

1

1st $14.54

$16.65

2nd $15.99

2

1st $17.45

$19.97

2nd $18.90

3

1st $20.36

$23.30

2nd $21.81

4

1st $23.99

$26.63

2nd $25.45

5

1st $28.35

$29.96

2nd $29.81

Prevailing Wage: Hourly Wage & Employer Contributions for Selected San Diego County Apprentices

Wage Year Two of Program

Basic Hourly

Wage

Employer Contributions

Total Hourly

Wages

Health &

Welfare

Pension

Vacation/

Holiday

Training Other

Electrician, Inside Wireman $18.90 $5.12 $2.83 -0- $0.56 $0.16 $27.57

Plumber/Pipetter/Steamtter $19.97 $6.02 $0.31 $1.79 $0.32 $0.39 $28.80

Operating Engineer $28.55 $7.95 $2.63 $2.82 $0.56 $0.17 $45.19

Sheet Metal $19.33 $3.42 $2.63 - 0 - $0.68 $0.46 $26.52

Laborer $19.01 $4.26 $0.39 $2.62 $0.64 $0.30 $27.22

Painter $14.21 $4.60 $0.15 $0.30 $0.34 $0.67 $20.27

Roofer $16.02 $4.76 $1.62 -0- $0.10 $0.20 $22.70

Heating, Ventilation & Air

Conditioning**

$19.62 $6.38 $1.13 -0- $0.70 $0.25 $28.08

Carpet $20.01 $6.00 $0.94 $0.23 $0.45 $0.15 $27.78

62

development funding from a broad base of contractors

and workers, these costs are nominal and have a high

return on investment in productivity and eciency.

Economist Peter Phillips found that doubling the rate of

unionization equals a 10-20% increase in productivity.

21

Depending on the trade classication and technical

requirements, apprenticeship programs run from three

to ve years (See table 5). From the onset, apprentices

receive hands-on jobsite experience, coupled with

technical in-class and laboratory-based instruction. Joint

labor-management apprenticeship programs provide

a career ladder to journey-level responsibilities and

wages. Apprentices can also earn wages and benets

with their on-the-job work even as they undergo

training. This provides opportunities for workers,

especially disadvantaged workers, to receive education

and training to enter middle-class construction careers

while still earning wages to pay their bills and support

their families. The apprentice starts with a portion of

journey-level wages in his or her rst year, usually in

the range of $12-$20 an hour, depending on the craft

and on conditions in the local job market. As he or she

reaches certain milestones in on-the-job hours and

in-class instruction, the apprentice receives a series of

wage increases until he or she graduates as a journey-

level worker (See table 3).

The apprenticeship-based career ladder, particularly in

joint labor-management apprenticeship partnerships,

helps contractors compete based on value, quality,

and eciency. Labor-management apprenticeship

programs help reduce crew composition costs

through incorporating apprenticeships into the project

workforce. Since apprentices work at lower wage

rates than journey-level workers in exchange for job

training, deploying apprentices to the job site can help

contractors reduce overall labor costs.

Labor-management apprenticeships also provide

contractors with workers well-versed in the most

up-to-date construction technology. Accomplishing

complicated construction tasks on tight deadlines

through the use of highly skilled workers also gives

employers an advantage that allows them to bid

projects with condence, knowing that their employees

can meet or exceed expectations. Apprenticeships also

give contractors the opportunity to create goodwill

in the communities where they work by hiring

workers specically from local zip codes and/or from

disadvantaged backgrounds.

Therefore, contractors who utilize workers who have

completed joint labor-management apprenticeships

achieve a strong competitive advantage, particularly

for large-scale industrial, commercial or municipal

construction projects . The benets of the ability to

deliver quality and safe workmanship at a rapid pace far

outweigh the perceived nancial advantage of using

lower-skilled workers who may be less costly, but whose

skill sets are inadequate to keep the job site safe and

productive. The track record of on-time and on-budget

project delivery and quality work performance has been

key to helping the Building and Construction Trades and

their signatory contractors to successfully compete for

and complete large, complex building projects.

Apprenticeship program requirements for selected crafts. Crafts require varying skills and therefore apprenticeship requirements dier across

trades.

Source: California Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Apprenticeship Standards, Public Works Apprentice Wage Sheets.

Graphic Modied From: Construction Apprenticeship Programs: Career Training for Californias Recovery, by Corinne Wilson, Center on Policy

Initiatives, 2009.

Table 5

Apprenticeship Wage increases dependent upon successful completion of training segments

Top 10 crafts sorted by total number of apprentices graduated from programs

Crafts Years On-the-job-hours Classroom hours/year

Electrician, Residential 3 4,800 160

Commercial/Industrial 5 8,000 160

Plumbing 4 7,200 200

Operating Engineer 4 6,000 144

Sheetmetal 4 6,500 160

Laborer 2 3,000 216

Painting & Decoration 3.5 7,000 114

Roofers 3.5 4,000 144

Plumbing 4 7,200 200

Air conditioning & refrigeration 5 7,500 216

Carpet, Linoleum & Soft Tile 4 6,400 160

63

Increasing Access to

Construction Jobs

New workers modes of entry into the construction

industry vary. Traditionally, skills of the construction

trade were passed down from family member to family

member. Today, however, a variety of pathways exist

to move new workers into the industry. One pathway

is connected to community colleges, trade schools,

and high school technical career training programs

that partner with regional contractors to create work

opportunities for their graduates. But these programs

provide limited in-class training and even more limited

on-the-job training and job placement opportunities

that are critical for successful long-term construction

employment. Typically, these programs provide up to

one to two years of introductory in-class skills training,

with the expectation that the worker will move into a

construction career by learning on-the-job skills as a

trainee or helper on projects.

However, without support after graduating from these

various programs, there is no guarantee the worker will

actually nd and retain employment over time. This

is especially true in the construction industry with its

cyclical nature and temporary work structure. Informal

job pathways also exist, mainly in the residential and

light commercial sectors. In these pathways workers,

usually with general maintenance or labor skills, move

into jobs through formal and informal referrals such

as unemployment oces, worker centers, or word of

mouth.

Still, the ideal way to enter the construction industry

is through a registered joint labor-management

apprenticeship program. This is an apprenticeship

program that is registered with the Department of

Labor and meets the minimum federal requirements.

The apprenticeship program is funded and managed

by both labor unions and contractors, meaning that

apprentices gain experiences that meet both their

educational needs and contractors needs. These

programs provide high quality, comprehensive technical

in-class training in a particular trade, and include

extensive on-the-job training in which apprentices

receive pay and benets while they build skills and

experience. Figure 27 ilustrates an ideal pathway to

green jobs. Figure 28 compares an apprenticeship-

based training program and a non-apprenticeship-

based program.

Apprentices typically complete their training in three

to ve years, depending on the requirements of the

specic trade. They then attain certied journeyworker

status and can expect that the union hiring hall will

dispatch them to continuous work opportunities. To

maintain updated certications, graduates of registered

apprenticeship programs must regularly return to

receive new training in the newest construction

practices and the latest tools and technologies,

like those focused on green and energy ecient

construction. Through this process of training and

re-training workers on the most advanced technologies

and construction processes, registered apprenticeship

and journey-worker training programs provide some

of the best ways to create a well-trained and adaptable

workforce as construction continues to adopt more

energy ecient practices.

Historically, there has been limited access to registered

joint-labor apprenticeship programs for minority

workers and women. Though recent positive changes

have increased diversity in the unionized construction

workforce, the numbers show that limited access

persists. This is reected in relatively lower levels of

representation of women, African American workers,

Asian American workers, and other minorities in these

training programs.

Increasing diversity requires a two-pronged approach.

The work opportunities in the industry need to be

increased overall. It then becomes easier to create

targeted hiring and support mechanisms to identify,

train, place, and retain minority construction workers in

skilled construction crafts.

The current economic downturn and the

disproportionately negative impact on the

construction industry has translated into diminishing

work opportunities for all workers. This has caused

apprenticeship programs generally to restrict the

number of apprentices they take. Access to training

in the construction industry, then, remains tied to

the performance of the broader economy and the

availability of work opportunities.

The mobile nature of the construction workforce

is another factor that aects access to jobs for new

workers, especially in tough economic times. For

example, when a large scale project promises the

creation of several thousand jobs, the bulk of those jobs

will be performed by workers already in the industry

who are unemployed or under-employed. Since

construction workers move from project to project and

employers try to hire the most experienced and best

trained workers, even large scale projects only provide

a limited number of opportunities for new workers.

For example, on an air conditioning system installation

project, a work crew may include six to ten journey-

level air conditioning mechanics along with two to

four apprentices--of which one or two may be new

apprentices.

It is important to recognize this structure allows this

system to be truly equitable over the long-term. Rather

than continuously trying to increase the numbers of

cheaper entry-level workers, it creates sustainable work

opportunities for existing workers in the industry over

their lifetimes and sustainably incoprates new workers.

Finally, collective bargaining agreements set general

guidelines for contractors to organize their work crews.

An employer might like to hire one journeyworker

and twelve apprentices, which is a more cost eective

arrangement for employers considering wage rates of

apprentices are lower than those of journeyworkers.

However, the reality is that this arrangement can

potentially result in inadequate supervision and

skill levels at work sites, leading to unsafe working

64

Recruitment &

Case Management

- 0rlver llcense

- 0aycare

- Jransportatlon

Pre-apprentlceshlp

- Applled Vath

- Applled Readlng

- lndustry Awarness

- Jherapy

- louslng

- lntervlew Skllls

- Safety Awarness

Reglstered

Apprentlceshlp

- Related Jechnlcal

lnstructlon

- ln-class lnstructlon

- 0n-the-Job

Jralnlng

lnergy

lmclency Projects

- Placement on energy emclency projects

- Pathways to mlddle class careers

- Career optlons ln multlple constructlon

sectors

Recruitment Training Placement Start Job Increase Skills & Wages

- un-pald tralnlng

- 0nly 40-200 hours

- No certlhcatlon

- 510-512/lr

- No enehts

- No job guarantees

- No pathway out of poverty

Non-Apprenticeship-Based Training: A Broken Pipeline

- Pre-apprentlceshlps provlde

job readiness skills, GED,

math & support services

- Cet pald whlle learnlng durlng

apprenticeship

- 0n the job plus classroom

training

- Placement through hlrlng halls - lncreased wages 8 benehts

after certain training and

experience requirements are met

- Contlnous opportunltles to return

for training

- Posslbllltles for promotlon,

increased salaries & certications

Registered Apprenticeship Pipeline: A Pathway to Better Opportunities

Figure 28: Comparing Construction Workforce Pipelines

Recruitment Training Placement Start Job Increase Skills & Wages

Figure 27: Pathway to Green Jobs

65

Foreman

Leads construction teams on site.

Increased salaries and certication.

Develops leadership skills.

Contractor

Owner of construction company.

Receives support from Union contractor

associations.

Journeyman

State-licensed.

Can work in various types of construction

including Industrial, Commercial

and Residential.

Apprentice (3-5 Years)

Works under direct supervision of Master or

Journey level worker.

Pre-Apprenticeship

Gains soft and hard skills to prepare for

union apprenticeship.

conditions and poor construction. Moreover, the

outnumbered journey- level workers would have to

devote more time to training new apprentices and less

to performing actual construction work themselves,

thereby slowing the construction process. Thus,

collective bargaining agreements usually dictate the

ratio of journey- to apprentice-level workers allowed

on work crews so as to achieve the best balance on the

worksite.

The best way to address the challenges of increasing

workers access to good construction jobs is by creating

a consistent stream of construction work opportunities.

The industrys new focus on green construction and

retrotting the existing building stock to improve

energy eciency represents such an opportunity.

As we discussed in Chapter Two, taking a deep green

approach to building retrots will maximize the

creation of good jobs in the construction industry. Deep

green also means connecting job training programs

to career pathways in the joint labor-management

apprenticeship training system. The challenge the

energy eciency market faces is to avoid creating

short-term jobs that provide a limited scope of training

and work opportunities. Through a basic weatherization

program, a worker might receive training just to convert

T8 uorescent to LED lighting. By contrast, an electrical

apprentice can learn how to change light xtures, pull

wires, set circuit breakers and terminate connections.

This opens up a lifelong career for him or her to perform

work on the entire electrical system of a building and to

build a comprehensive set of skills. If energy eciency

retrots work becomes scarce, a temporary, short-term

worker will be left with few transferable skills to nd

other jobs. Meanwhile, the apprenticeship-trained

electrician will access many other job opportunities

throughout his or her career, including journey-level

worker, foreman, and contractor (See gure 29). This

kind of long-range view of the sector is needed to mend

our current economic situation, instead of short-term

thinking that could push the economy into another

crisis when temporary work fades away.

Conclusion

Understanding construction industry dynamics is

critical to building an environmentally ecient/

green construction market that takes the high road

with respect to creating careers and building a strong

workforce. How investors, governments, developers,

and contractors make decisions in response to market

dynamics greatly determines the type and number of

jobs this emerging market will create. Policy tools such

as Project Labor Agreements and Community Workforce

Agreements exist so that as new jobs emerge, the

focus stays on ensuring that these are good, green

careers that are accessible to everyone. These policy

tools provide a template to set standards in the new,

emerging energy eciency market. PLAs and CWAs

work best when coupled with committed leadership

and robust compliance mechanisms.

The existing joint labor-management apprenticeship

training infrastructure, which workers and contractors

work together to design, is an invaluable tool for the

emerging energy eciency industry. It provides rigorous

and eective training for workers who need to be up-

to-date on the latest developments in new technology

and green construction practices, and brings important

advantages to contractors. Robust existing infrastructure

in the construction industry, like these apprenticeships,

can provide a foundation from which to grow the

energy eciency market.

With these construction industry practices in mind,

the next two chapters will delve into constructing a

deep green energy eciency program and explore

lessons from specic examples. Chapter Five combines

information about the construction industry with

innovative tools to support an ideal energy eciency

retrot program. Chapter Six explores themes from

real, innovative projects in energy eciency. Together

these chapters oer insight into building a program that

considers the unique characteristics of the construction

industry and can bring energy eciency to scale in the

face of the current global economic crisis.

Figure 29: Occupational Hierarchy

66

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Surge Analysis and The Wave Plan MethodDokumen126 halamanSurge Analysis and The Wave Plan Methodmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- A Meta Analytic Review of Relationships Between Team Design Features and Team Performance - StewartDokumen28 halamanA Meta Analytic Review of Relationships Between Team Design Features and Team Performance - StewartdpsmafiaBelum ada peringkat

- Enhancement of Efficiency of Biogas Dige PDFDokumen6 halamanEnhancement of Efficiency of Biogas Dige PDFmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Hdpe Rates Pe80Dokumen1 halamanHdpe Rates Pe80mailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Hdpe Rates Pe100Dokumen1 halamanHdpe Rates Pe100mailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Effect of Hydraulic and Geometrical Properties On Stepped Cascade Aeration SystemDokumen11 halamanEffect of Hydraulic and Geometrical Properties On Stepped Cascade Aeration Systemmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Modeling pump startup and shutdown transients in the same simulationDokumen5 halamanModeling pump startup and shutdown transients in the same simulationmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Joint Efficiency Factors For Seam-Welded Factory-Made Pipeline BendsDokumen18 halamanJoint Efficiency Factors For Seam-Welded Factory-Made Pipeline Bendsmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Hydraulic Design of Storm Sewers With Excel CourseDokumen41 halamanHydraulic Design of Storm Sewers With Excel CourseRonal Salvatierra100% (1)

- Properly Sizing Pumps and Pipes for Variable Viscosity Non-Newtonian FluidsDokumen3 halamanProperly Sizing Pumps and Pipes for Variable Viscosity Non-Newtonian Fluidsmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Air Valve Orifice SizeDokumen1 halamanAir Valve Orifice Sizemailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- By Dr. A Jon Kimerling, Professor Emeritus, Oregon State UniversityDokumen3 halamanBy Dr. A Jon Kimerling, Professor Emeritus, Oregon State Universitymailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Design of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA AlgorithmDokumen8 halamanDesign of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA Algorithmmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Centrifugal Pump SelectionDokumen25 halamanCentrifugal Pump SelectionAbhay Sisodia100% (1)

- Modeling A Pump Start-Up Transient Event in HAMMER - OpenFlowsDokumen22 halamanModeling A Pump Start-Up Transient Event in HAMMER - OpenFlowsmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- The Secrets of Breakpoint ChlorinationDokumen26 halamanThe Secrets of Breakpoint Chlorinationmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- HDPE Pipe InformationDokumen24 halamanHDPE Pipe InformationTylerBelum ada peringkat

- Flow Control ValvesDokumen24 halamanFlow Control Valvesmk_chandru100% (1)

- Design of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA AlgorithmDokumen8 halamanDesign of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA Algorithmmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Computation of Afflux With Particular Reference To Widening of Bridges On A RoadwayDokumen8 halamanComputation of Afflux With Particular Reference To Widening of Bridges On A Roadwaymailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Siewtanyimboh Warm 2012 Epanet PDXDokumen23 halamanSiewtanyimboh Warm 2012 Epanet PDXmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Flow Control ValvesDokumen6 halamanFlow Control Valvesmailmaverick8167100% (1)

- Design of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA AlgorithmDokumen8 halamanDesign of Surge Tank For Water Supply Systems Using The Impulse Response Method With The GA Algorithmmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Flow Control ValvesDokumen6 halamanFlow Control Valvesmailmaverick8167100% (1)

- CHP Old Projects Pump DimensionsDokumen2 halamanCHP Old Projects Pump Dimensionsmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- 5822Dokumen16 halaman5822rambinodBelum ada peringkat

- Is 9523 Ductile Iron FittingsDokumen32 halamanIs 9523 Ductile Iron FittingsKathiravan Manimegalai100% (2)

- 12 Shibly RahmanDokumen34 halaman12 Shibly Rahmanmailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- Surge Tank Design Considerations ForDokumen14 halamanSurge Tank Design Considerations ForPatricio Muñoz Proboste100% (1)

- PG 67 IS 456Dokumen1 halamanPG 67 IS 456mailmaverick8167Belum ada peringkat

- FLEXI READING Implementing GuidelinesDokumen94 halamanFLEXI READING Implementing GuidelinesMay L BulanBelum ada peringkat

- ANT 302 - Intro To Cultural Anthropology: UNIQUE #'S: 31135, 31140, 31145, 31150, 31155, 31160, 31165 & 31175Dokumen8 halamanANT 302 - Intro To Cultural Anthropology: UNIQUE #'S: 31135, 31140, 31145, 31150, 31155, 31160, 31165 & 31175Bing Bing LiBelum ada peringkat

- CreativewritingsyllabusDokumen5 halamanCreativewritingsyllabusapi-261908359Belum ada peringkat

- What Type of Student Are YouDokumen2 halamanWhat Type of Student Are YouElizabeth Reyes100% (3)

- Cooperative Learning Lesson PlanDokumen2 halamanCooperative Learning Lesson Planapi-252467565Belum ada peringkat

- Editable Rpms PortfolioDokumen31 halamanEditable Rpms Portfolioengelbert picardalBelum ada peringkat

- Module 14 14Dokumen2 halamanModule 14 14Fenny Lou CabanesBelum ada peringkat

- COMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Dokumen7 halamanCOMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Severus S PotterBelum ada peringkat

- JaychandranDokumen5 halamanJaychandranINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH STUDIESBelum ada peringkat

- K To 12 Report Cherylyn D DevanaderaDokumen3 halamanK To 12 Report Cherylyn D DevanaderaCherylyn De Jesus DevanaderaBelum ada peringkat

- Guide For Preparing Chairman'sPlanningGuide (CPGS) AndMEAEntriesDokumen60 halamanGuide For Preparing Chairman'sPlanningGuide (CPGS) AndMEAEntriesDianne BishopBelum ada peringkat

- A Point About The Quality of The English Translation of Gulistan of Saadi by RehatsekDokumen11 halamanA Point About The Quality of The English Translation of Gulistan of Saadi by RehatsekIJ-ELTSBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Photography 1 Skyline HighSchoolDokumen2 halamanDigital Photography 1 Skyline HighSchoolmlgiltnerBelum ada peringkat

- English Lesson Plan 2C2IADokumen5 halamanEnglish Lesson Plan 2C2IAPaula JanBelum ada peringkat

- Vice Chancellor's message highlights WUM's missionDokumen115 halamanVice Chancellor's message highlights WUM's missionhome143Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluation 4 Lesson Plan - Reducing FractionsDokumen1 halamanEvaluation 4 Lesson Plan - Reducing Fractionsapi-340025508Belum ada peringkat

- Written Task No.4Dokumen2 halamanWritten Task No.4Cherry Lou De GuzmanBelum ada peringkat

- Pe Lesson Plan 2 16 17Dokumen7 halamanPe Lesson Plan 2 16 17api-350775200Belum ada peringkat

- Legal Professional Seeks Dynamic CareerDokumen4 halamanLegal Professional Seeks Dynamic CareerLowlyLutfurBelum ada peringkat

- Course Handout of Contrastive Analysis & Error Analysis (English-Arabic) by DRSHAGHIDokumen30 halamanCourse Handout of Contrastive Analysis & Error Analysis (English-Arabic) by DRSHAGHIDr. Abdullah Shaghi100% (1)

- PR 1 Week 3 Q2Dokumen3 halamanPR 1 Week 3 Q2Jays Eel100% (2)

- Portfolio UpdatedDokumen4 halamanPortfolio Updatedapi-548862320Belum ada peringkat

- NCHE - Benchmarks For Postgraduate StudiesDokumen73 halamanNCHE - Benchmarks For Postgraduate StudiesYona MbalibulhaBelum ada peringkat

- Strategy For CAT Preparation by SpanedeaDokumen26 halamanStrategy For CAT Preparation by SpanedeaspanedeaBelum ada peringkat

- Resume Making Workshop - IIT BombayDokumen49 halamanResume Making Workshop - IIT BombayAnshul KhandelwalBelum ada peringkat

- Hydraulics & Fluid Mechanics Handout 2012-2013Dokumen4 halamanHydraulics & Fluid Mechanics Handout 2012-2013Tushar Gupta0% (1)

- Chapter 4 - WEBER - SummaryDokumen2 halamanChapter 4 - WEBER - SummaryinsaankhanBelum ada peringkat

- Social Studies Lesson Plan Farm To PlateDokumen2 halamanSocial Studies Lesson Plan Farm To Plateapi-540101254Belum ada peringkat