Supply Chain

Diunggah oleh

Siva Krishna Reddy Nallamilli0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

212 tayangan8 halamansupply chain

Judul Asli

supply chain

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inisupply chain

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

212 tayangan8 halamanSupply Chain

Diunggah oleh

Siva Krishna Reddy Nallamillisupply chain

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 8

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 772 February 2014

AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION OF SUPPLY

CHAIN SUSTAINABILITY AND RISK

MANAGEMENT

Jay Varzandeh, Kamy Farahbod, Jake Zhu

California State University, San Bernardino

ABSTRACT

It seems, in todays business environment, practitioners and academicians are

increasingly becoming conscious of the importance of two trends in supply chain

management namely risk management and supply chain sustainability. However, while

the supply chain risk management (SCRM) categories, such as disruptions, delays,

systems risk and the others, and their drivers and mitigation techniques have been

identified theoretically for some time, there is minimal empirical evidence of the real life

application of SCRM methods by supply chain managers. The same is true about the

theory versus the real life application of supply chain sustainability methods. In other

words, many supply chain managers identify sustainability as a strategic business driver,

but use it as a mere public relation tool.

Therefore, while these two concepts are receiving growing attention by supply chain

managers, and are related to each other, the extent to which the techniques of SCRM and

sustainability are used by the practitioners remains to be determined.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the level of understanding of the Supply Chain

sustainability on the part of supply chain managers, and to determine to what extent

practitioners address this strategic issue in their chains.

The methodology involves the use of a primary questioner to identify what supply chain

executives deem as important concerns for sustainability in their chains, and how these

factors relate to the ones reported in academic literature. Based on our findings in the

first part, a second survey will determine whether supply chain managers are addressing

their sustainability issues effectively by using the methods that are recommended by

academicians.

INTRODUCTION

Today, many firms are addressing and discussing sustainability as a strategic concern of

paramount importance. It relates to meeting the present needs without imposing or

compromising the ability to meet the needs of the future generations. More specifically,

supply chain sustainability is associated with organizations social responsibilities towards

present and future community needs. This means bringing supply chain partners into a

collaborative arrangement to work together to achieve sustainability throughout the entire

supply chain. That is, the traditional collaboration to move information, material, and

funds would have to be reevaluated. For that, organizations should realize that supply

chain sustainability involves many aspects of supply chain network including

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 773 February 2014

environmental resources, employees, community, customers and their reputations and

perceptions.

According to Mollenkopf and Tate (2011), supply chain sustainability is achieved by

working with upstream suppliers and downstream chain partners to analyze operations

and processes in order to identify opportunities to find alternative, environmentally

friendly ways of producing products and delivering services. Krajewski et al. (2013),

however, offers a broader definition involving thee basic elements: (1) financial

responsibility to all monetary stakeholders, (2) environmental responsibility to current

and future generations, and (3) social and ethical responsibility to the whole society.

Supply chains use sustainability as a strategic element for at least three reasons

(Mollenkopf and Tate, 2011); risk management, government regulations, and supply

chain influence. Haklik, 2012, identifies the impact of ISO certification on sustainability

through the ISO 14001 guidelines that require awareness of a companys impact on the

environment, acceptance of responsibility for those impacts, the expectation that harmful

impacts will be reduced or eliminated, and assignment of responsibility for environmental

impacts.

According to Mollenkopf and Tate, sustainability programs pose some challenges that

chain members have to address. These may include corporate structure and culture,

communication issues in the chain, and products and processes specifics that require

tremendous upfront investments for sustainability (Mollenkopf and Tate, 2011).

A 2010 audit of more than 230 enterprise sustainability programs found the best-in-class

performers were three times more likely to appoint a chief sustainability officer.

Moreover, those the best-in-class that were seriously implementing sustainability

initiatives, reported an average of almost 80% increase in equipment effectiveness,

almost 20% reduction in energy consumption, and almost 30% reduction in emissions

versus the previous year (Slaybaugh, 2010).

A 2011 survey of supply chain greening programs found that more than 80% of the

supply chain professionals favored suppliers with green business practices. However,

only 25% had any type of carbon footprint evaluation process to measure their

suppliers performance. The Institute of Supply Management (ISM) suggests the use of

several guidelines and measurement tools to benchmark and achieve the sustainability

objectives in practice. They include: ASPI Eurozone (Advanced Sustainable

Performance Indices) to identify those who are committed to sustainable development

and corporate social responsibility (CSR), and Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes (DJSI)

to measure the financial performance of global companies that lead in sustainability.

Brown and Ulgiati (1999) suggest Emergy Sustainability Index (ESI) to measure

supply chain sustainability. It is defined as the ratio of emergy yield ratio (EYR) over the

environmental loading ratio (ELR). While the academic ground is laid and the research

demonstrates the enthusiasm of the supply chain executives, it is of vital importance to

investigate and understand the reasons for apparent gap between the theory and practice

of sustainability issues, measurements, and challenges.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the level of understanding of the Supply Chain

sustainability on the part of supply chain managers, and to determine to what extent

practitioners address this strategic issue in their chains, and how these factors relate to the

ones reported in academic literature.

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 774 February 2014

SUSTAINABILITY: A STRATEGIC DRIVER

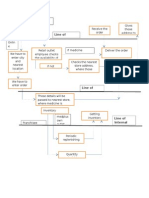

Chopra et al., 2013 describes six major drivers within supply chain spectrum (Figure 1).

Although all are strategically related to sustainability within supply chain, but the holistic

approach to sustainability remains to be determined and implemented. The review of the

literature in the earlier section associates sustainability with corporate social

responsibility within the supply chain framework. Figure 2 shows a framework, which

defines a broader spectrum within suppliers, producers and customers in the cradle to

grave cycle of a product. The three dimensions (suppliers, Producers, and customers),

displayed in Figure 2, bring much more insights into how an organization defines its

supply chain drivers for profitability and sustainability, by showing their interaction to

create value for the customer. Figure 3 illustrates a modification of Figure 1 in which the

six supply-chains logistical and cross-functional drivers are redesigned to assure supply

chain long-term profitability, as well as sustainability.

Figure 1

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 775 February 2014

Figure 2 and the supply chain structural drivers in Figure 1 signify that products should

be evaluated from concept development through disposal in their life cycle for supply

chain sustainability, and this process should include people, resources, employees,

community and the resulted companys perception and reputation. It is a strategic

survival approach that all organizations should consider and implement.

Organizations should be aware and concerned about how their suppliers, on their supply

side of Figure 2, and their distributors, warehouses, retailors, etc., on their customer side

of Figure 2, maintain the sustainability issues within their chains. Some major

organizations such as GE and Walmart have supplier audits, and BMW has developed

recycling and reuse of their parts to reduce waste and environmental pollution.

Sustainability requires a host of diverse issues within the specified sections in Figure 2.

These issues are related to product life cycle assessment, product design, processes and

their stabilities, logistics and reverse logistics and their components, rules and regulations

(domestic and international), and industry standards.

Figure 2

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 776 February 2014

While the academicians have laid the ground and the research demonstrates the

enthusiasm of the supply chain executives, it is of vital importance to investigate and

understand the reasons for apparent gap between the theory and practice of supply chain

sustainability (SCS). The questionnaire used in this study aims at identifying what supply

chain executives deem as important concerns for sustainability in their chains, and how

these factors relate to the ones reported in academic literature. Moreover, the

questionnaire studies the sustainability concerns and practices among small, medium, and

large size organizations.

METHODOLOGY AND FINDINGS

This study has directed surveys to three classes of organizations based on their number of

employees: small, medium, and large sizes. 28 small, 31 medium, and 16 large

organizations are surveyed by phone and in actual meetings on the issues which have

been discussed in sustainability literatures as are listed in Table 2. The results of the

survey on organizational awareness and supply chain audits are presented in Table 1.

Figure 3

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 777 February 2014

Table 1

Organizations Organizational Awareness Supply Chain Audits

Small (less than 100 employees) 8% 2%

Medium (100-500 employees) 45% 8%

Large (500 or more employees) 73% 11%

Table 2

Organizational Awareness Supply Chain Audits

Does your company consider

sustainability as a business objective,

Or does it have a sustainability code of

conduct?

Does your company have a visible

sustainability program to manage its

chain partners?

Do all your employees, shareholders,

and other stakeholders have Knowledge

or training in principles of

sustainability?

Does your company audit the upstream

Or downstream chain partners for

sustainability issues?

Does your company have a chief

sustainability executive (CSE), or an

executive in charge of sustainability?

Will your chain partners face positive or

negative consequences as a result of

their sustainability efforts or lack of?

Is your company planning to allocate

more resources to sustainability

training and projects in the future?

Is your chain planning more

collaboration to achieve sustainability

in the future?

The results in Table 1 are alarming and show how organizations overlook sustainability

as a core strategic element to achieve efficiency and responsiveness in long term. The

survey also showed that over 70% of all organizations had difficulty in relating the listed

issues to supply chain sustainability. 43% of the respondents believed that achieving what

the supply chain audits require, as are explained in sustainability domains, would be

impractical and not possible. In particular, some practitioners argued that in todays

competition and global business activities, auditing may not be as effective and fiscally

economical. The results also, highlighted the fact that the smaller is the organization the

less that organization is aware of supply chain sustainability and the needs for pursuing it.

Interestingly, according to the results, the smaller size organizations that are aware of

supply chain sustainability have planned and pursued supply chain audits more. That is,

25% of small size organizations that are aware of supply chain sustainability also have

supply chain audits in contrast to 18% and 15% of medium and large size organizations,

respectively. That may be due to their shorter supply chain domain compared to the

medium and large organizations. Nevertheless, the results in this survey show that the

large size organizations have more awareness about the importance of such strategic issue

in their quest for achieving efficiency and responsiveness, but they have put less effort to

plan and achieve that.

Proceedings of ASBBS Volume 21 Number 1

ASBBS Annual Conference: Las Vegas 778 February 2014

CONCLUSION AND REMARKS

Chopra et.al, 2013, suggests that in order to achieve the supply chain strategic objectives,

a chain must position itself somewhere in the efficiency to responsiveness spectrum,

and then manipulate six supply chain drivers of facilities, inventory, transportation,

information, sourcing, and pricing, to reach and maintain this position. In this context,

responsiveness is defined as the ability of the chain to respond to wide ranges of

quantities demanded, to meet short lead times, to handle a large variety of products, to

build innovative products, and to meet a very high service level.

As indicated before, in todays business environment, sustainability is becoming

increasingly important. Therefore, it should be considered a major part of the

organizations supply chain strategy. This means that we need to consider responsiveness

in a broader context, which includes sustainability. Namely, responsiveness should be

defined as the abilities previously mentioned, plus the ability to achieve sustainability.

While the strategic importance of sustainability has been discussed by the academicians

and substantiated by business professionals, its place in the overall objectives of business

organizations has not been established yet. The result, as shown in this paper, is a lack of

comprehensive sustainability program that is championed by effective supply chain

managers and fully supported by top management. This research, however, is addressing

the lively issue of sustainability in a dynamic and ever changing supply chain

environment, which could easily force its members to change their practices in short

order. That is why we suggest further research, perhaps in a year or two, is needed to see

how the importance and practice of sustainability in business organizations is changing.

REFERENCES

Brown, M. T., Ulgiati, S. (1999). Emergy Evaluation of Natural Capital and Biosphere

Services. AMBIO. Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 31-42.

Chopra, S., Meindl, P. (2013). Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and

Operation. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Haklik, J. E. (2012). ISO 14001 and Sustainable Development. February. Retrieved

February 12, 2012. www.trst.com/sustainable.htm.

Krajewski, L. J., Ritzman, L. P., Malhotra, M. K. (2013). Operations Management, 10

th

ed., Pearson, Boston, MA.

Mollenkopf, D. A., Tate, W. L. (2011). Green and Lean Supply Chains. CSCMP

Explores. Vol. 8, pp. 1-17.

Slaybaugh, R. (2010). Sustainable Productions Star Performers. eSide Supply

Management. Vol. 3, No. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

www.ism.ws/pubs/eside/esidearticle.cfm?ItemNumber=19978.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- SPC Examples with SolutionsDokumen4 halamanSPC Examples with SolutionsSiva Krishna Reddy Nallamilli100% (1)

- Rani TextilesDokumen2 halamanRani TextilesSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Atherosclerosis - Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentDokumen4 halamanAtherosclerosis - Causes, Symptoms & TreatmentSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Control Charts For ClassDokumen10 halamanControl Charts For ClassSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Anaparthi Servies Softwares Hardwares Computer ServicesDokumen1 halamanAnaparthi Servies Softwares Hardwares Computer ServicesSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Pharmaceuticals August 2014Dokumen55 halamanPharmaceuticals August 2014Siva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Toyota Global Site - The Origin of The Toyota Production SystemDokumen2 halamanToyota Global Site - The Origin of The Toyota Production SystemSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- QUALITY Focus Key to Transforming Management EducationDokumen8 halamanQUALITY Focus Key to Transforming Management EducationSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Lean Manufacturing The Maruti Way - Business LineDokumen2 halamanLean Manufacturing The Maruti Way - Business LineSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Exports DataDokumen2 halamanIndian Exports DataSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Toyota Global Site - The Origin of The Toyota Production SystemDokumen2 halamanToyota Global Site - The Origin of The Toyota Production SystemSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Atchyuta Rao ResumeDokumen2 halamanAtchyuta Rao ResumeSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Pharmaceuticals August 2014Dokumen55 halamanPharmaceuticals August 2014Siva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Topics on Quality, Lean Manufacturing and Productivity ImprovementDokumen16 halamanTopics on Quality, Lean Manufacturing and Productivity ImprovementSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Hindering Indian Export Growth and Potential SolutionsDokumen16 halamanFactors Hindering Indian Export Growth and Potential SolutionsSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Medplus Service BlueprintDokumen1 halamanMedplus Service BlueprintSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Creative Briefs 51Dokumen15 halamanCreative Briefs 51Siva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Performance ManagementDokumen1 halamanPerformance ManagementSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Sales and Distribution Process of Itc Vivel SoapsDokumen7 halamanSales and Distribution Process of Itc Vivel SoapsPrateek Goel100% (1)

- HP Deskjet - Supply ChainDokumen15 halamanHP Deskjet - Supply Chainsaurabhku12100% (4)

- PM Modi Wants This Bihar Success Story Replicated - NDTVProfitDokumen3 halamanPM Modi Wants This Bihar Success Story Replicated - NDTVProfitSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi Favourite To Win 'Time Person of The Year' PollDokumen2 halamanPrime Minister Narendra Modi Favourite To Win 'Time Person of The Year' PollSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Qatar Airways Takes Delivery of Its First Airbus A380 - The Economic TimesDokumen2 halamanQatar Airways Takes Delivery of Its First Airbus A380 - The Economic TimesSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Bharti Airtel Announces New Organization Structure For India OperationsDokumen1 halamanBharti Airtel Announces New Organization Structure For India OperationsSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- PediasureDokumen4 halamanPediasureSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Amazon Hires 80,000 Seasonal Holiday Workers - ET RetailDokumen3 halamanAmazon Hires 80,000 Seasonal Holiday Workers - ET RetailSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Biolab TestDokumen2 halamanBiolab TestSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Profitability Analysis With Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing: A Case Study in A HotelDokumen30 halamanCustomer Profitability Analysis With Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing: A Case Study in A HotelSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Management Case: Blue Dart Express LimitedDokumen8 halamanManagement Case: Blue Dart Express LimitedAravind MaitreyaBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Profitability AnalysisDokumen5 halamanCustomer Profitability AnalysisSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- EMDR Therapy Treatment of Grief and Mourning in Times of COVID19 CoronavirusJournal of EMDR Practice and ResearchDokumen13 halamanEMDR Therapy Treatment of Grief and Mourning in Times of COVID19 CoronavirusJournal of EMDR Practice and ResearchIsaura MendezBelum ada peringkat

- Crimes and Civil Wrongs: Wrong Adjetivo X Substantivo (Legal English) Right Adjetivo X Substantivo (Legal English)Dokumen10 halamanCrimes and Civil Wrongs: Wrong Adjetivo X Substantivo (Legal English) Right Adjetivo X Substantivo (Legal English)mraroBelum ada peringkat

- Unit III International ArbitrageDokumen14 halamanUnit III International ArbitrageanshuldceBelum ada peringkat

- 111Dokumen16 halaman111Squall1979Belum ada peringkat

- Midtern Exam, Living in IT EraDokumen43 halamanMidtern Exam, Living in IT EraJhazz Landagan33% (3)

- UI Part B 1stDokumen2 halamanUI Part B 1stArun KumarBelum ada peringkat

- CSS 9-Summative TEST 3Dokumen2 halamanCSS 9-Summative TEST 3herbert rebloraBelum ada peringkat

- Insiderspower: An Interanalyst PublicationDokumen10 halamanInsiderspower: An Interanalyst PublicationInterAnalyst, LLCBelum ada peringkat

- International Electric-Vehicle Consumer SurveyDokumen11 halamanInternational Electric-Vehicle Consumer SurveymanishBelum ada peringkat

- LL.M in Mergers and Acquisitions Statement of PurposeDokumen3 halamanLL.M in Mergers and Acquisitions Statement of PurposeojasBelum ada peringkat

- Compare Quickbooks Plans: Buy Now & Save Up To 70%Dokumen1 halamanCompare Quickbooks Plans: Buy Now & Save Up To 70%Agustus GuyBelum ada peringkat

- Case StudyDokumen2 halamanCase StudyMicaella GalanzaBelum ada peringkat

- Sierra Gainer Resume FinalDokumen2 halamanSierra Gainer Resume Finalapi-501229355Belum ada peringkat

- Realizing Your True Nature and Controlling CircumstancesDokumen43 halamanRealizing Your True Nature and Controlling Circumstancesmaggie144100% (17)

- Taqvi: Bin Syed Muhammad MuttaqiDokumen4 halamanTaqvi: Bin Syed Muhammad Muttaqiمحمد جواد علىBelum ada peringkat

- Maxwell-Johnson Funeral Homes CorporationDokumen13 halamanMaxwell-Johnson Funeral Homes CorporationteriusjBelum ada peringkat

- Pernille Gerstenberg KirkebyDokumen17 halamanPernille Gerstenberg KirkebymanufutureBelum ada peringkat

- Instrument Used To Collect Data Topic: Survey On Some Problems Single Parent Encountered in The Community of Parafaite HarmonieDokumen5 halamanInstrument Used To Collect Data Topic: Survey On Some Problems Single Parent Encountered in The Community of Parafaite HarmonieDumissa MelvilleBelum ada peringkat

- Cash Flow and Financial Statements of Vaibhav Laxmi Ma Galla BhandarDokumen14 halamanCash Flow and Financial Statements of Vaibhav Laxmi Ma Galla BhandarRavi KarnaBelum ada peringkat

- Pointers-Criminal Jurisprudence/gemini Criminology Review and Training Center Subjects: Book 1, Book 2, Criminal Evidence and Criminal ProcedureDokumen10 halamanPointers-Criminal Jurisprudence/gemini Criminology Review and Training Center Subjects: Book 1, Book 2, Criminal Evidence and Criminal ProcedureDivina Dugao100% (1)

- Research ProposalDokumen4 halamanResearch Proposalapi-285161756Belum ada peringkat

- URC 2021 Annual Stockholders' Meeting Agenda and Voting DetailsDokumen211 halamanURC 2021 Annual Stockholders' Meeting Agenda and Voting DetailsRenier Palma CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Broadband AccessDokumen39 halamanTypes of Broadband AccessmasangkayBelum ada peringkat

- Ningam Siro NR Parmar OverruledDokumen32 halamanNingam Siro NR Parmar OverruledSardaar Harpreet Singh HoraBelum ada peringkat

- SUMMARYDokumen44 halamanSUMMARYGenelle Mae MadrigalBelum ada peringkat

- Nature & EnvironmentalismDokumen2 halamanNature & EnvironmentalismEba EbaBelum ada peringkat

- Single Entry System Practice ManualDokumen56 halamanSingle Entry System Practice ManualNimesh GoyalBelum ada peringkat

- Investment in TurkeyDokumen41 halamanInvestment in TurkeyLalit_Sharma_2519100% (2)

- UK Health Forum Interaction 18Dokumen150 halamanUK Health Forum Interaction 18paralelepipicoipiBelum ada peringkat

- Structure of Banking in IndiaDokumen22 halamanStructure of Banking in IndiaTushar Kumar 1140Belum ada peringkat