SC Asfiksia Bule @

Diunggah oleh

Iga AmandaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

SC Asfiksia Bule @

Diunggah oleh

Iga AmandaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

578 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO.

6, JUNE 2009

O R I G I N A L C O M M U N I C A T I O N

INTRODUCTION

C

esarean section still poses a lot of challenges to

clinicians in low-resource settings. Fetal out-

come after cesarean section is of serious con-

cern, especially if part of the reason for surgery was to

salvage the fetus. It is usually performed when a vaginal

delivery would put the babys or mothers life or health at

risk, although in recent times it has been also performed

upon request for births that would otherwise have been

normal.

1

Cesarean section has been shown to be a safe

operation for both the mother and the fetus,

1,3

and in

many countries around the world there has been a dra-

matic increase in its frequency.

1-5

Previously, the mortal-

ity was almost 100% for the mother, especially in devel-

oping countries with poor resources, the major causes

being infections, hemorrhage, and poor health care.

6

Improved health care delivery in terms of personnel and

facilities have all contributed to the dramatic decrease in

mortality seen during the last century.

6,7

In an attempt to

reduce the rising trend of cesarean delivery worldwide,

obstetricians now offer, among other options, the trial of

labor more readily to women even a with previous his-

tory of cesarean section.

5-7

Several studies both in devel-

oped and developing countries have shown that it is not

only feasible but safe.

1-5

This new trend is a welcome

development especially in our environment, where there

is a strong aversion for cesarean delivery informed by

the desire of mothers to have vaginal delivery.

7,8

Despite the improved obstetric practice, considerable

care is still required to maintain and improve the rates of

maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

9-11

We have,

therefore, carried out a prospective study to evaluate

fetal outcome for the various indications for cesarean

section in a teaching hospital in Nigeria.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective study was carried out at the Usmanu

Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital (UDUTH),

Sokoto, Nigeria, between January 2006 and April 2007.

The hospital has a 500-bed space and an average annual

delivery rate of 2500. Ethical approval was obtained

from the ethical committee of the teaching hospital

before the study was commenced.

All patients that were to have cesarean section within

the study period were consecutively recruited into the

study. The following information were obtained using a

structured questionnaire: maternal sociodemographic

variables and obstetric history, fetal gender, fetal birth

weight, and gestational age, with emphasis on indica-

tions for the cesarean section and perinatal outcome.

Author Affiliations: Departments of Paediatrics (Mr Onankpa) and Obstet-

rics and Gynaecology (Mr Ekele), Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching

Hospital, PMB 2370, Sokoto, Sokoto State, Nigeria.

Corresponding Author: Ben Onankpa, MBBS, FWACP, Department of Pae-

diatrics, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, PMB 2370, Sokoto,

Sokoto State, Nigeria (benonankpa@yahoo.com).

Objective: To evaluate fetal outcome for the various indica-

tions for cesarean section.

Methodology: A review of all cases of cesarean section that

were done in the maternity unit at Usmanu Danfodiyo Uni-

versity Teaching Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria, between January

2006 and April 2007, with emphasis on indications and peri-

natal outcome.

Results: There were 2562 total deliveries within the study peri-

od and 112 perinatal deaths giving a perinatal mortality rate

of 43.7 per 1000 live births. Cesarean section accounted for

216 of the deliveries (8.4%) with 24 perinatal deaths (11.1%).

Perinatal mortality from Cesarean sections accounted for

21.4% of the total deaths with severe birth asphyxia respon-

sible for most perinatal deaths, 17 of 24 (70.8%). There were

174 emergency sections with 22 perinatal deaths, while 42

elective sections had 2 perinatal deaths. The main indica-

tions for cesarean section were cephalopelvic dispropor-

tion, 86 (39.8%); previous section plus an obstetric abnormal-

ity, 39 (18.1%); and prolonged obstructed labor, (10.2%), with

perinatal deaths of 3, 2 and 11, respectively.

Conclusions: The perinatal mortality among the cesarean

deliveries were 11.1%, and the main cause of death was

severe birth asphyxia. Emergency cesarean section was

more likely than elective to result in a perinatal loss. The

indication with the poorest fetal outcome was prolonged

obstructed labor.

Keyword: obstetrics/gynecology

J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:578-581

Fetal Outcome Following Cesarean Section in

a University Teaching Hospital

Ben Onankpa, MBBS, FWACP; Bissallah Ekele, MBBS, FWACS

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 6, JUNE 2009 579

CAESAREAN SECTION AND FETAL OUTCOME

The cadre of obstetrician/pediatricians at every surgery

was also documented.

The ndings are presented as simple percentages and

frequencies. c

2

Test, where appropriate, was used for the

statistical analysis. Two-sided signicance was put at

less than .05.

RESULTS

There were 2562 total deliveries within the study

period. Males were 1,371 (53.5%), while females were

1,191 (46.5%), giving a male-female ratio of 1.2:1. Vag-

inal deliveries accounted for 2260 (88.2%), instrumental

vaginal deliveries were 86 (3.4%), while cesarean sec-

tions were 216 (8.4%) of the total deliveries. Teenage

mothers aged less than 16 years who had cesarean sec-

tion were 38 (17.6%), those aged 16 to 19 years were 42

(19.4%), 20 to 29 years were 66 (30.6%), 30 to 39 years

were 43 (19.9%), while those aged 40 years and above

were 27 (12.5%). One hundred twelve babies died giv-

ing a perinatal mortality rate of 43.7 per 1000 live births.

Of the 216 cesarean sections, males were 128 (59.3%),

while females were 88 (40.7%). All the cesarean sec-

tions were performed under general anesthesia with a

pediatric team in attendance. Elective and emergency

cesarean sections accounted for 42 (19.4%) and 174

(80.6%), respectively.

Perinatal mortality from vaginal deliveries was 81

(3.6%), instrumental vaginal deliveries was 7 (8.1%),

while that of cesarean sections was 24 (11.1%) of the

total deaths. Emergency cesarean sections were 174,

with 22 perinatal deaths, while elective cesarean sec-

tions were 42 with 2 perinatal deaths (Table 1), c

2

=

2.128, p = .01131, Fisher).

The main indication for cesarean section was cepha-

lopelvic disproportion. There were 86 (39.8%) cases of

cephalopelvic disproportion, previous section plus an

obstetric abnormality were 39 (18.1%), prolonged

obstructed labor was 36 (16.7%), and hypertensive dis-

orders of pregnancy were 22 (10.2%) (Table 2).

There were 24 perinatal deaths following the cesar-

ean sections (11.1%), males were 15 (62.5%) and

females were 9 (37.5%). Cephalopelvic disproportion,

previous section plus an obstetric abnormality, pro-

longed obstructed labor and hypertensive disorders of

pregnancy accounted for 3 (12.5%) 2 (8.3%), 11 (45.8%)

and 4 (16.7%) perinatal deaths, respectively.

Of the 22 perinatal deaths following emergency

cesarean sections, 77.3% (17 of 22) of the surgeries were

done by trainee obstetricians, while the pediatric team at

all surgeries were junior registrars (Table 3). Severe birth

asphyxia accounted for 17 (70.8%) mortalities (Table 4).

Prolonged obstructed labor with 30.5% (11 of 36) deaths

had the poorest fetal outcome.

DISCUSSION

Globally, obstetric practice has witnessed an increas-

ing frequency in cesarean sections with continuing

growth in the last decades.

1,5,7,12

The need to curtail this

alarming rate has led to increasing pressure being placed

on obstetricians to alter practice. In Nigeria and in most

other countries of low-resource settings, where cesarean

deliveries are not readily accepted by the populace, ex-

ibility within the framework of good obstetric practice is

the desired goal.

1,7,8

The main indications for cesarean section in our

study were cephalopelvic disproportion (39.8%) and

previous cesarean section plus an obstetric abnormality

(18.1%). This is in keeping with previous ndings from

other centers within the country.

2,5,7

This is however, in

contrast to ndings from developed countries, where the

common indications are previous cesarean section and,

more recently, increasing maternal choice for a cesarean

section for any reason whatever.

1,12-14

In this study cepha-

lopelvic disproportion was the cause of prolonged

obstructed labor in most of those that had prolonged

obstructed labor as the indication for cesarean section.

The observed high perinatal mortality rate of 43.7

per 1000 live births for our study was comparable with

reports from other developing nations.

4-7

Lower values

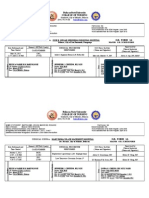

Table 1. Caesarean Section Type and Fetal

Outcome (n = 216)

a,b

Type of Surgery n (%) Deaths, n (%)

Elective 42 (19.4) 2 (4.8)

Emergency 174 (80.6) 22 (12.6)

Total 216 (100) 24 (11.1)

a

c

2

= 2.128

b

p = .01131 (Fisher)

Table 2. Maternal Indications for Cesarean Section and Fetal Outcome (n = 216)

Maternal Indications n Fetal Mortality, n (%)

Cephalopelvic disproportion 86 3 (3.5)

Previous cesarean/obstetric abnormality 39 2 (5.1)

Prolonged obstructed labor 36 11 (30.6)

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 22 4 (18.2)

Postdatism 16 2 (12.5)

Antepartum hemorrhage 12 1 (8.3)

Others 5 1 (20.0)

Total 216 24 (11.1)

580 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 6, JUNE 2009

CAESAREAN SECTION AND FETAL OUTCOME

of less than 10 per 1000 live births have been quoted

from advanced countries.

6,10,11

The overall perinatal mortality amongst the cesarean

deliveries was 11.1% for the study. This is similar to g-

ures cited from studies from similar settings

2,4,5

but

higher than gures from the developed countries.

9-11

Perinatal mortality following emergency cesarean sec-

tions accounted for 19.6% (22 of 112) of the total peri-

natal deaths within the study period. In this study,

although cesarean section was only 8.4% of the total

deliveries, it had higher perinatal deaths of 11.1% com-

pared to 3.6% and 8.1% from vaginal and instrumental

vaginal deliveries, respectively. This pattern was also

found in studies from other poor-resource settings.

2,4-7

Emergency cesarean section deliveries continue to

form the bulk of abdominal deliveries in our center partly

because most patients come to the hospital after an unsuc-

cessful attempt at home delivery, when complications

would have arisen. In some cases the fetal head is so

impacted into the pelvis that delivery of the head at cesar-

ean section poses an extra challenge to the surgeon.

15

Our study has shown that perinatal deaths were

higher in surgeries carried out by trainee obstetricians

compared to consultants. It was also noted that all the 24

perinatal deaths were attended to by pediatric junior res-

idents. These observations could be attributed to the

experiences of surgeons rather than operative tech-

niques.

6

The type of anesthesia did not differ between

the emergency cesarean sections and the elective ones.

Both emergency and elective cesarean sections were

done under general anesthesia.

The indications with poor fetal outcome were pro-

longed obstructed labor, hypertensive disorders of preg-

nancy, and cephalopelvic disproportion. This pattern is

similar to previous works.

2,5,6

The main cause of death

was severe birth asphyxia, 17 of 24 (70.8%). Children

from the group with the elective cesarean section had

also less-frequent asphyxia and considerably less-fre-

quent resuscitation than the children from the group

with the emergency cesarean sections. The facts from

the literature are similar.

6,9

There might be need to review

the type of resuscitation in such babies and/or consider

other options for delivery, especially in settings where

aversion to abdominal delivery already exist.

There is also need for more attention/supervision by

consultant obstetricians and pediatricians, especially in

low-resource settings, where electronic fetal monitoring

might not be available to assist in decision making, sur-

gery, and resuscitation. The very poor fetal outcomes in

those with prolonged obstructed labor need a critical

appraisal by obstetricians, probably to consider other

options outside abdominal delivery. Fetal outcome for

options like symphysiotomy might not be too different,

but the mother would have been spared the uterine scar

with all its implications!

REFERENCES

1. Treffers P, Pel M. The rising trend for caesarean birth. BMJ.1993;307:1017-

1019

2. Okpere EE,Oronsaye AU, Imoedehe DAG. Pregnancy and delivery

after caesarean section: a review of 494 cases. Trop J Obstet Gynecol.

1981;3:45-48.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.Guideline for

vaginal delivery after previous caesarean birth. Int J Obstet Gynecol.

1996;52;90-98.

4. Aisien AO, Lawson JO, Adebayo AA. A five year appraisal of caesarean

section in a northern Nigeria University Teaching Hospital. Niger Postgrad

Med J. 2002;3:146-150.

5. Swende Tz, Agida ET, Jogo AA. Elective caesarean section at Federal

Medical Centre Makurdi, North central Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2007;16(4):372-

374.

6. Elvidi-Gasparovic V, Klepac-Pulanic T, Peter B. Maternal and fetal out-

come in elective versus emergency caesarean section in a developing

Table 4. Morbidity/Mortality Following Caesarean Section in 24 Newborns

Morbidity n Mortality, n (%)

Perinatal asphyxia 26 17 (70.9)

Prematurity with sepsis 14 3 (12.5)

Neonatal jaundice with neonatal sepsis 11 2 (8.3)

Multiple congenital anomaly 2 2 (8.3)

Total 53 24 (100)

Table 3. Type of Surgery, Experience of the Surgeon and the Pediatrician at Surgery to Fetal Outcome

(n = 216)

a,b

Type of Surgery n Mortality Surgeon Pediatrician

Consultant Resident Consultant Resident

Elective 42 2 28 (0)

c

14 (2) 0 (0) 42 (2)

Emergency 174 22 82 (5) 92 (17) 0 (0) 174 (22)

Total 216 24 110 (5) 106 (19) 0 (0) 216 (24)

a

c

2

= 0.5742

b

p = .6196 (Fisher)

c

Mortality with respect to the experience of the surgeon/pediatric team in paracentesis

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 6, JUNE 2009 581

CAESAREAN SECTION AND FETAL OUTCOME

country. Coll Antropol. 2006;1:113-118.

7. Ezechi OC, Kalu BKE, Njokanma FO, Ndububa V, Nwokoro CA, Okeke

GCE. Trial of labour after a previous caesarean section: A private Hospital

experience. Annals of African Medicine. 2005;3:113-117.

8. Oladipo OT, Lamina MA, Sule-Odu AO. Maternal morbidity and mortality

associated with elective caesarean delivery at a University teaching hospi-

tal in Nigeria. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;2:110-114.

9. Gaym A. Perinatal mortality audit at Jimma hospital, south western Ethio-

pia. Ethiop. J Health Dev. 2000;14(3):335-343.

10. Joseph KS, Kramer MS. Canadian infant mortality: 1994 update [letter].

Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:161-163.

11. Howell EM, Blondel B. International infant mortality rates: bias from

reporting differences. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:850-852.

12. Lomas J. Holding backs the tide of caesareans. BMJ. 1988;297:569-570.

13. Devendra K Arulkumaran S. Should Doctors Perform an Elective Caesar-

ean Section on Request? Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32:577-582.

14. Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Obstetricians say yes to maternal

request for elective caesarean section: a survey of current opinion. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97:15-16.

15. Ekele BA. Impacted head at Caesarean section in obstructed labour:

push or pull? Trop Doctor. 2001;31:38-39. n

We Welcome Your Comments

The Journal of the National Medical Association

welcomes your Letters to the Editor about

articles that appear in the JNMA or issues

relevant to minority healthcare. Address

correspondence to EditorJNMA@nmanet.org.

Reproducedwith permission of thecopyright owner. Further reproductionprohibited without permission.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Finseth PPT ReviewDokumen206 halamanFinseth PPT ReviewTracy NwanneBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- CT Scan Kepala Ekspertisi Dr. Sandy IstantoDokumen9 halamanCT Scan Kepala Ekspertisi Dr. Sandy IstantoIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Prehospital Use of Magnesium SulfateDokumen9 halamanPrehospital Use of Magnesium SulfateNefri TiawarmanBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide Benefits of PodiatryDokumen20 halamanA Guide Benefits of PodiatryIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Bab 55 Asma BronkialDokumen6 halamanBab 55 Asma BronkialAudrey BudionoBelum ada peringkat

- Greetings and Introductory QuestionDokumen12 halamanGreetings and Introductory QuestionIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- 4.4.7.5 APEC PROM Guidelines 11-13-13 PDFDokumen7 halaman4.4.7.5 APEC PROM Guidelines 11-13-13 PDFAnnisa Rizki Ratih PratiwiBelum ada peringkat

- Abbreviated TitleDokumen230 halamanAbbreviated TitleRico MamboBelum ada peringkat

- Abbreviated TitleDokumen230 halamanAbbreviated TitleRico MamboBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Factors Associated With Birth Asphyxia in Phramongkutklao HospitalDokumen7 halamanRisk Factors Associated With Birth Asphyxia in Phramongkutklao HospitalIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Fitness Assessment Norm Data 11'10Dokumen6 halamanFitness Assessment Norm Data 11'10Kumar VasanthBelum ada peringkat

- Fetal Response To Acute Hypoxic Ischemia and HIEDokumen29 halamanFetal Response To Acute Hypoxic Ischemia and HIEDevi ParamitaBelum ada peringkat

- Term Prelabour Rupture of Membranes (Term Prom) (C-Obs 36) Review Mar 14Dokumen12 halamanTerm Prelabour Rupture of Membranes (Term Prom) (C-Obs 36) Review Mar 14Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- CS US Meneker and DeclerqueDokumen15 halamanCS US Meneker and DeclerqueIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Int J Qual Health Care 1999 Kritchevsky 283 91Dokumen9 halamanInt J Qual Health Care 1999 Kritchevsky 283 91Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Anesthesia For Emergency Cesarean Section in A Parturient With Noonan Syndrome 2155 6148.1000368Dokumen3 halamanAnesthesia For Emergency Cesarean Section in A Parturient With Noonan Syndrome 2155 6148.1000368Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- AsphyxiaDokumen9 halamanAsphyxiaMuhammad IsmailBelum ada peringkat

- Mid Test Journal (Exercise)Dokumen7 halamanMid Test Journal (Exercise)Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Factors of Birth AsphyxiaDokumen5 halamanRisk Factors of Birth AsphyxiaromeoennyBelum ada peringkat

- 5.7 Asphyxia Neonatorum - Incidence in Cape Town. C.D. Molteno, A.F. Malan and H. de v. HeeseDokumen4 halaman5.7 Asphyxia Neonatorum - Incidence in Cape Town. C.D. Molteno, A.F. Malan and H. de v. HeeseIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Anesthesia For Emergency Cesarean Section in A Parturient With Noonan Syndrome 2155 6148.1000368Dokumen3 halamanAnesthesia For Emergency Cesarean Section in A Parturient With Noonan Syndrome 2155 6148.1000368Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- Premature Rupture of Membranes PromDokumen15 halamanPremature Rupture of Membranes PromIga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- UAS Inggris (Final Test)Dokumen2 halamanUAS Inggris (Final Test)Iga AmandaBelum ada peringkat

- HBVGuide 09Dokumen78 halamanHBVGuide 09clavipratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Effects of Aerobic Training Resistance Training orDokumen20 halamanEffects of Aerobic Training Resistance Training orBAIRON DANIEL ECHAVARRIA RUEDABelum ada peringkat

- Efficacy of Homoeopathy in SarcoidosisDokumen77 halamanEfficacy of Homoeopathy in SarcoidosisDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomBelum ada peringkat

- Journal ClubDokumen12 halamanJournal ClubAnonymous ibmeej9Belum ada peringkat

- Resume Atiyeh KaboudvandDokumen2 halamanResume Atiyeh Kaboudvandarian tejaratBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Sitologi UrineDokumen10 halamanJurnal Sitologi UrineAjip JenBelum ada peringkat

- Coronavirus VaccineDokumen3 halamanCoronavirus VaccineDayana RicardezBelum ada peringkat

- Gout Presentation Group 2 Defines Metabolic Disorder and ManagementDokumen10 halamanGout Presentation Group 2 Defines Metabolic Disorder and ManagementVon Valentine MhuteBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing responsibilities for generic medicationsDokumen6 halamanNursing responsibilities for generic medicationsAngelito LeritBelum ada peringkat

- New PRC Form SampleDokumen8 halamanNew PRC Form SampleLanie Esteban EspejoBelum ada peringkat

- NSE121 - Care PlanDokumen7 halamanNSE121 - Care Planramyharoon2004Belum ada peringkat

- IMMUNOLOGY COURSE MODULE ON IMMUNOGLOBULINSDokumen8 halamanIMMUNOLOGY COURSE MODULE ON IMMUNOGLOBULINSboatcomBelum ada peringkat

- Guideline - Anesthesia - RodentsDokumen2 halamanGuideline - Anesthesia - Rodentsdoja catBelum ada peringkat

- RETDEMDokumen2 halamanRETDEMDoneva Lyn MedinaBelum ada peringkat

- Perineal Care: Michael H. Esmilla, RN, MANDokumen15 halamanPerineal Care: Michael H. Esmilla, RN, MANHannah Leigh CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- Phylum Class Order Genera: Apicomplexa Haematozoa Haemosporida Plasmodium Piroplasmida Coccidia EimeriidaDokumen39 halamanPhylum Class Order Genera: Apicomplexa Haematozoa Haemosporida Plasmodium Piroplasmida Coccidia EimeriidaMegbaruBelum ada peringkat

- Heart Disease in Pregnancy GuideDokumen3 halamanHeart Disease in Pregnancy GuideNasehah SakeenahBelum ada peringkat

- 02-09 2022 Pharm Pediatrics 2022 R4Dokumen44 halaman02-09 2022 Pharm Pediatrics 2022 R4Amira HelayelBelum ada peringkat

- Asepsis and Aseptic Practices in The Operating RoomDokumen6 halamanAsepsis and Aseptic Practices in The Operating RoomMichelle ViduyaBelum ada peringkat

- Neonatal Exchange TransfusionDokumen33 halamanNeonatal Exchange TransfusionedrinsneBelum ada peringkat

- A) Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients With Migrainous Infarction - Accepted and Final Publication From Elsevier1-s2.0-S030384671730344X-mainDokumen3 halamanA) Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients With Migrainous Infarction - Accepted and Final Publication From Elsevier1-s2.0-S030384671730344X-mainRodrigo Uribe PachecoBelum ada peringkat

- Brain Tumor Segmentation and Detection Using Nueral NetworksDokumen9 halamanBrain Tumor Segmentation and Detection Using Nueral Networksjoshi manoharBelum ada peringkat

- Low Frequency Tens "Transcutaneos Electrical Nervestimulation"Dokumen72 halamanLow Frequency Tens "Transcutaneos Electrical Nervestimulation"Florian BeldimanBelum ada peringkat

- Annotated Bibliography On Internet AddictionDokumen4 halamanAnnotated Bibliography On Internet AddictionJanet Martel100% (3)

- Rights PharmaDokumen1 halamanRights PharmaMargaret ArellanoBelum ada peringkat

- 12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudyDokumen6 halaman12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudymailcdgnBelum ada peringkat

- Daftar PustakaDokumen4 halamanDaftar PustakajhnaidillaBelum ada peringkat

- HNP3Dokumen9 halamanHNP3dev darma karinggaBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment and Concept Map Care Plan: Joseph GorospeDokumen5 halamanAssessment and Concept Map Care Plan: Joseph Gorospeapi-497389977Belum ada peringkat

- Differential Diagnosis of Scalp Hair FolliculitisDokumen8 halamanDifferential Diagnosis of Scalp Hair FolliculitisandreinaviconBelum ada peringkat