Honoria Raymundo, Etc. Praying That The Resolution of This

Diunggah oleh

Karen Abella0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

14 tayangan4 halamanmnbvcx

Judul Asli

CIVPRO

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inimnbvcx

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

14 tayangan4 halamanHonoria Raymundo, Etc. Praying That The Resolution of This

Diunggah oleh

Karen Abellamnbvcx

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 4

1

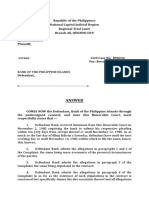

CARMEN C. VIUDA DE ORDOVEZA, petitioner,

vs.

HONORIA RAYMUNDO, respondent.

Petitioner is the appellee and respondent the appellant in a

case now pending on appeal in the Court of Appeals, entitled

Domingo Ordoveza vs. Honoria Raymundo, and numbered

44763 in the records of the court. The period for the filing of

the appellant's brief in that case expired on March 20, 1936.

On March 31, 1936 the Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal

for failure of the appellant to file her brief within the time

prescribed by the rules of the court, and ordered that after

fifteen days the record of the case be remanded to the court

below. On April 6, 1936 the appellant filed a petition for

reconsideration of the order dismissing the appeal, which

petition was denied on April 8, 1936. A second petition for

reconsideration was filed by the appellant, and in view thereof

the Court of Appeals on April 14, 1936, passed the following

resolution:

Upon consideration of the second petition of the attorneys for

the appellant in case G. R. 44763, Domingo Ordoveza vs.

Honoria Raymundo, etc. praying that the resolution of this

court of March 31, 1936, dismissing the appeal for failure to

file their brief be reconsidered; in view of the reasons given in

said petition and the special circumstances of the case, said

resolution is hereby set aside and the appeal reinstated;

provided, however, that the attorneys for the appellant shall

file their printed brief within five days from notice hereof.

On April 17,1936 the appellee filed a motion praying that the

resolution above quoted be reconsidered and set aside, which

motion was denied.

Upon the foregoing state of facts, the appellee filed this petition

for a writ of certiorariwith a view to having declared null and

void the order of the Court of Appeals restating the appeal.

Petitioner now contends (1) that the Court of Appeals had no

power to reinstate the appeal because it lost jurisdiction of the

case on April 5, 1936, in that fifteen days had already elapsed

from March 20, 1936, the date when the period fixed for the

filing of the appellant's brief expired; and (2) that granting that

the Court of Appeals retained jurisdiction of the case, it had no

authority to grant the appellant an additional period of five

days within which to file her brief.

By section 145-P of the Revised Administrative Code as

amended by Commonwealth Act No. 3, and in virtue of the

resolution adopted by the Court of Appeals on February 8,

1936, the rules of the Supreme Court governing the filing of

briefs and the dismissal of appeals are applicable to cases

cognizable by the Court of Appeals.

Rules 23 and 24 of the Supreme Court are pertinent to the

consideration of the present petition. The rules read as follows:

23. Motions for extension of time for the filing of briefs must be

presented before the expiration of the time mentioned in Rules

21 and 22, or within a time fixed by special order of the court.

No more than one extension of time for the filing of briefs shall

be allowed, and then only for good and sufficient cause shown,

to be demonstrated by affidavit.

24. If the appellant, in any civil case, fails to serve his brief

within the time prescribed by these rules the court may, on

motion of the appellee and notice to the appellant, or on its

own motion, dismiss the bill of exceptions or the appeal.

1. The first contention of the petitioner rests on the theory

developed in his argument that upon the failure of the

appellant to file her brief within the time prescribed by the

rules of the court, her appeal became, ipso facto, dismissed.

Consequently, he argues that at the expiration of the period of

fifteen days from March 20, 1936, the Court of Appeals lost

jurisdiction of the case, and had, therefore, no power to

reinstate the appeal. This view finds no support in the rules of

this court. Rule 24 above transcribed clearly indicates the

contrary view when it says that upon failure of the appellant to

file his brief within the period prescribed by the rules, the

court "may", on motion of the appellee and notice to the

appellant, or its own motion, dismiss the bill of exceptions or

the appeal. The use of the word "may" implies that the matter

of dismissing the appeal or not rests within the sound

discretion of the court, and that failure of the appellant to file

his brief within the time prescribed by the rules does not have

the effect of dismissing the appeal automatically. Viewed in

this light, the period of fifteen days must be counted in the

case under consideration not from March 20, 1936, but from

March 31, 1936. Having been entered on April 14, 1936, the

order reinstating the appeal came within such fifteen-day

period.

2. Granted that the Court of Appeals still had jurisdiction of

the case when it reinstated the appeal, it seem reasonable to

conclude that it also had authority to grant the appellant an

additional period of five days within which to file her brief. Rule

23 provides in specific terms that the court may by special

order fix a time within which motions for extension of time for

the filing of briefs must be presented. It would seem to be

within the spirit of this rule to hold that the court may grant

either the appellant or appellee an additional time for the filing

of his brief even without any previous application therefor.

Moreover, as the Supreme Court of the United States has aptly

observed, "it is always in the power of the court to suspend its

own rules, or to except a particular case from its operation,

whenever the purposes of justice require it." (U.

S. vs. Breitling, 20 How., 252; 15 Law. ed., 900, 902.)

We conclude that the Court of Appeals had authority to

reinstate the appeal in the aforesaid case numbered 44763 in

its records, and to grant the appellant an additional period of

file days within which to file her brief.

The petition for a writ of certiorari must be denied. So ordered.

G.R. No. L-64013 November 28, 1983

UNION GLASS & CONTAINER CORPORATION and CARLOS

PALANCA, JR., in his capacity as President of Union Glass

& Container Corporation, petitioners,

vs.

THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION and

CAROLINA HOFILEA, respondents.

This petition for certiorari and prohibition seeks to annul and

set aside the Order of the Securities and Exchange

Commission, dated September 25, 1981, upholding its

jurisdiction in SEC Case No. 2035, entitled "Carolina Hofilea,

Complainant, versus Development Bank of the Philippines, et

al., Respondents."

Private respondent Carolina Hofilea, complainant in SEC

Case No. 2035, is a stockholder of Pioneer Glass

Manufacturing Corporation, Pioneer Glass for short, a

domestic corporation engaged in the operation of silica mines

and the manufacture of glass and glassware. Since 1967,

Pioneer Glass had obtained various loan accommodations from

the Development Bank of the Philippines [DBP], and also from

other local and foreign sources which DBP guaranteed.

As security for said loan accommodations, Pioneer Glass

mortgaged and/or assigned its assets, real and personal, to the

DBP, in addition to the mortgages executed by some of its

corporate officers over their personal assets. The proceeds of

said financial exposure of the DBP were used in the

construction of a glass plant in Rosario, Cavite, and the

operation of seven silica mining claims owned by the

corporation.

It appears that through the conversion into equity of the

accumulated unpaid interests on the various loans amounting

to P5.4 million as of January 1975, and subsequently

increased by another P2.2 million in 1976, the DBP was able to

gain control of the outstanding shares of common stocks of

Pioneer Glass, and to get two, later three, regular seats in the

corporation's board of directors.

Sometime in March, 1978, when Pioneer Glass suffered serious

liquidity problems such that it could no longer meet its

financial obligations with DBP, it entered into a dacion en pago

agreement with the latter, whereby all its assets mortgaged to

DBP were ceded to the latter in full satisfaction of the

corporation's obligations in the total amount of

P59,000,000.00. Part of the assets transferred to the DBP was

the glass plant in Rosario, Cavite, which DBP leased and

subsequently sold to herein petitioner Union Glass and

Container Corporation, hereinafter referred to as Union Glass.

On April 1, 1981, Carolina Hofilea filed a complaint before the

respondent Securities and Exchange Commission against the

DBP, Union Glass and Pioneer Glass, docketed as SEC Case

No. 2035. Of the five causes of action pleaded therein, only the

first cause of action concerned petitioner Union Glass as

transferee and possessor of the glass plant. Said first cause of

2

action was based on the alleged illegality of the

aforesaid dacion en pagoresulting from: [1] the supposed

unilateral and unsupported undervaluation of the assets of

Pioneer Glass covered by the agreement; [2] the self-dealing

indulged in by DBP, having acted both as stockholder/director

and secured creditor of Pioneer Glass; and [3] the wrongful

inclusion by DBP in its statement of account of P26M as due

from Pioneer Glass when the same had already been converted

into equity.

Thus, with respect to said first cause of action, respondent

Hofilea prayed that the SEC issue an order:t.hqw

1. Holding that the so called dacion en pago conveying all

the assets of Pioneer Glass and the Hofilea personal

properties to Union Glass be declared null and void on the

ground that the said conveyance was tainted

with.t.hqw

A. Self-dealing on the part of DBP which was acting

both as a controlling stockholder/director and as

secured creditor of the Pioneer Glass, all to its

advantage and to that of Union Glass, and to the

gross prejudice of the Pioneer Glass,

B. That the dacion en pago is void because there was

gross undervaluation of the assets included in the so-

called dacion en pago by more than 100% to the

prejudice of Pioneer Glass and to the undue

advantage of DBP and Union Glass;

C. That the DBP unduly favored Union Glass over

another buyer, San Miguel Corporation,

notwithstanding the clearly advantageous terms

offered by the latter to the prejudice of Pioneer Glass,

its other creditors and so-called 'Minority

stockholders.'

2. Holding that the assets of the Pioneer Glass taken over

by DBP and part of which was delivered to Union Glass

particularly the glass plant to be returned accordingly.

3. That the DBP be ordered to accept and recognize the

appraisal conducted by the Asian Appraisal Inc. in 1975

and again in t978 of the asset of Pioneer Glass.

1

In her common prayer, Hofilea asked that DBP be sentenced

to pay Pioneer Glass actual, consequential, moral and

exemplary damages, for its alleged illegal acts and gross bad

faith; and for DBP and Union Glass to pay her a reasonable

amount as attorney's fees.

2

On April 21, 1981, Pioneer Glass filed its answer. On May 8,

1981, petitioners moved for dismissal of the case on the

ground that the SEC had no jurisdiction over the subject

matter or nature of the suit. Respondent Hofilea filed her

opposition to said motion, to which herein petitioners filed a

rejoinder.

On July 23, 1981, SEC Hearing Officer Eugenio E. Reyes, to

whom the case was assigned, granted the motion to dismiss for

lack of jurisdiction. However, on September 25, 1981, upon

motion for reconsideration filed by respondent Hofilea,

Hearing Officer Reyes reversed his original order by upholding

the SEC's jurisdiction over the subject matter and over the

persons of petitioners. Unable to secure a reconsideration of

the Order as well as to have the same reviewed by the

Commission En Banc, petitioners filed the instant petition for

certiorari and prohibition to set aside the order of September

25, 1981, and to prevent respondent SEC from taking

cognizance of SEC Case No. 2035.

The issue raised in the petition may be propounded thus: Is it

the regular court or the SEC that has jurisdiction over the

case?

In upholding the SEC's jurisdiction over the case Hearing

Officer Reyes rationalized his conclusion thus:t.hqw

As correctly pointed out by the complainant, the present

action is in the form of a derivative suit instituted by a

stockholder for the benefit of the corporation, respondent

Pioneer Glass and Manufacturing Corporation, principally

against another stockholder, respondent Development

Bank of the Philippines, for alleged illegal acts and gross

bad faith which resulted in the dacion en

pagoarrangement now being questioned by complainant.

These alleged illegal acts and gross bad faith came about

precisely by virtue of respondent Development Bank of the

Philippine's status as a stockholder of co-respondent

Pioneer Glass Manufacturing Corporation although its

status as such stockholder, was gained as a result of its

being a creditor of the latter. The derivative nature of this

instant action can also be gleaned from the common

prayer of the complainant which seeks for an order

directing respondent Development Bank of the Philippines

to pay co-respondent Pioneer Glass Manufacturing

Corporation damages for the alleged illegal acts and gross

bad faith as above-mentioned.

As far as respondent Union Glass and Container

Corporation is concerned, its inclusion as a party-

respondent by virtue of its being an indispensable party to

the present action, it being in possession of the assets

subject of the dacion en pago and, therefore, situated in

such a way that it will be affected by any judgment

thereon,

3

In the ordinary course of things, petitioner Union Glass, as

transferee and possessor of the glass plant covered by

the dacion en pago agreement, should be joined as party-

defendant under the general rule which requires the joinder of

every party who has an interest in or lien on the property

subject matter of the dispute.

4

Such joinder of parties avoids

multiplicity of suits as well as ensures the convenient, speedy

and orderly administration of justice.

But since petitioner Union Glass has no intra-corporate

relation with either the complainant or the DBP, its joinder as

party-defendant in SEC Case No. 2035 brings the cause of

action asserted against it outside the jurisdiction of the

respondent SEC.

The jurisdiction of the SEC is delineated by Section 5 of PD No.

902-A as follows:t.hqw

Sec. 5. In addition to the regulatory and adjudicative

function of the Securities and Exchange Commission

over corporations, partnerships and other forms of

associations registered with it as expressly granted under

existing laws and devices, it shall have original and

exclusive jurisdiction to hear and decide cases involving:

a] Devices and schemes employed by or any acts, of the

board of directors, business associates, its officers or

partners, amounting to fraud and misrepresentation

which may be detrimental to the interest of the public

and/or the stockholders, partners, members of

associations or organizations registered with the

Commission

b] Controversies arising out of intra-corporate or

partnership relations, between and among stockholders,

members or associates; between any or all of them and

the corporation, partnership, or association of which they

are stockholders, members or associates, respectively;

and between such corporation, partnership or

association and the state insofar as it concerns their

individual franchise or right to exist as such entity;

c] Controversies in the election or appointments of

directors, trustees, officers or managers of such

corporations, partnerships or associations.

This grant of jurisdiction must be viewed in the light of the

nature and function of the SEC under the law. Section 3 of PD

No. 902-A confers upon the latter "absolute jurisdiction,

supervision, and control over all corporations, partnerships or

associations, who are grantees of primary franchise and/or

license or permit issued by the government to operate in the

Philippines ... " The principal function of the SEC is the

supervision and control over corporations, partnerships and

associations with the end in view that investment in these

entities may be encouraged and protected, and their activities

pursued for the promotion of economic development.

5

It is in aid of this office that the adjudicative power of the SEC

must be exercised. Thus the law explicitly specified and

3

delimited its jurisdiction to matters intrinsically connected

with the regulation of corporations, partnerships and

associations and those dealing with the internal affairs of such

corporations, partnerships or associations.

Otherwise stated, in order that the SEC can take cognizance of

a case, the controversy must pertain to any of the following

relationships: [a] between the corporation, partnership or

association and the public; [b] between the corporation,

partnership or association and its stockholders, partners,

members, or officers; [c] between the corporation, partnership

or association and the state in so far as its franchise, permit or

license to operate is concerned; and [d] among the

stockholders, partners or associates themselves.

The fact that the controversy at bar involves the rights of

petitioner Union Glass who has no intra-corporate relation

either with complainant or the DBP, places the suit beyond the

jurisdiction of the respondent SEC. The case should be tried

and decided by the court of general jurisdiction, the Regional

Trial Court. This view is in accord with the rudimentary

principle that administrative agencies, like the SEC, are

tribunals of limited jurisdiction

6

and, as such, could wield only

such powers as are specifically granted to them by their

enabling statutes.

7

As We held in Sunset View Condominium

Corp. vs. Campos, Jr.:

8

t.hqw

Inasmuch as the private respondents are not

shareholders of the petitioner condominium corporation,

the instant cases for collection cannot be a 'controversy

arising out of intra-corporate or partnership relations

between and among stockholders, members or

associates; between any or all of them and the

corporation, partnership or association of which they are

stockholders, members or associates, respectively,' which

controversies are under the original and exclusive

jurisdiction of the Securities & Exchange Commission,

pursuant to Section 5 [b] of P.D. No. 902-A. ...

As heretofore pointed out, petitioner Union Glass is involved

only in the first cause of action of Hofileas complaint in SEC

Case No, 2035. While the Rules of Court, which applies

suppletorily to proceedings before the SEC, allows the joinder

of causes of action in one complaint, such procedure however

is subject to the rules regarding jurisdiction, venue and joinder

of parties.

9

Since petitioner has no intra-corporate

relationship with the complainant, it cannot be joined as party-

defendant in said case as to do so would violate the rule or

jurisdiction. Hofileas complaint against petitioner for

cancellation of the sale of the glass plant should therefore be

brought separately before the regular court But such action, if

instituted, shall be suspended to await the final outcome of

SEC Case No. 2035, for the issue of the validity of the dacion

en pago posed in the last mentioned case is a prejudicial

question, the resolution of which is a logical antecedent of the

issue involved in the action against petitioner Union Glass.

Thus, Hofileas complaint against the latter can only prosper if

final judgment is rendered in SEC Case No. 2035, annulling

the dacion en pago executed in favor of the DBP.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is hereby granted, and the

questioned Orders of respondent SEC, dated September 25,

1981, March 25, 1982 and May 28, 1982, are hereby set aside.

Respondent Commission is ordered to drop petitioner Union

Glass from SEC Case No. 2035, without prejudice to the filing

of a separate suit before the regular court of justice. No

pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.1wph1.t

G.R. No. L-12902

CEFERINO MARCELO, plaintiff-appellant,

vs.

NAZARIO DE LEON, defendant-appellee.

Pedro D. Maldia and San Vicente and Jardiel for appellant.

Inciong and Bacalso for appellee.

BENGZON, J.:

The plaintiff has appealed from the order of judge Jose N.

Leuterio of the Nueva Ecija court of first instance, dismissing

his complaint whereby he had asked that defendant be

required to vacate a parcel of land and to pay damages. The

dismissal rested on two grounds, (a) the case pertained to the

Court of Agrarian Relations; and (b) as attorney-in-fact of the

true owner of the land, the plaintiff had no right to bring the

action.

The record disclose that on February 4, 1957, Ceferino

Marcelo, filed in the justice of the peace court of San Antonio,

Nueva Ecija, a complaint to recover possession of a lot of 2,000

square meters belonging to Severino P. Marcelo (who had given

him a full power-of-attorney) which was held by defendant "on

the understanding that one-half of all the products raised in

the occupied area, would be given" to the landowner. The

complaint alleged that after plaintiff had assumed the

administration of Severino Marcelo's properties, defendant

delivered the products corresponding to the owner; but when

in September 1956, plaintiff notified defendant that in addition

to giving half of the produce, he would have to pay a rental of

two pesos per month, the latter refused, and continued

refusing to pay such additional charges. Wherefore,

complainant prayed for judgment ordering defendant to leave

the premises and to pay damages and costs.

The defendant questioned the court's jurisdiction, arguing that

the matter involved tenancy relations falling within the

authority of the Agrarian Court; he also challenged the

capacity of plaintiff to sue. He lost in the justice of the peace

court; however, on appeal to the court of first instance, he

raised the same issues on a motion to dismiss, and then his

views prevailed.

In this appeal, plaintiff insists he merely filed ejectment or

detainer proceedings, which fall within the justice of the peace

court's jurisdiction. He claims the lot to be residential, and not

agricultural. On this point, His Honor noted that "the land

covered by the title of plaintiff's principal covers an area of

59,646 square meters situated in the barrio of San Mariano,

San Antonio, Nueva Ecija. This land obviously is agricultural,

and it is too much to presume that barrio folks would occupy

an area of 2,000 square meters more or less of land for a

residence. The cultivation of the land by the defendant and the

sharing of the products thereof with the owner of the land

characterize the relationship between the defendant and the

plaintiff's principal as one of the landlord and tenant.

Indeed, from the allegations of the complaint, one could

conclude that defendant had physical possession of the land

for the purpose of cultivating it and giving the owner a share in

the crop. This was agricultural tenancy of the kind called

"share tenancy". In judging this relationship, the 2-pesos-a-

month-rental alleged in the complaint may be disregarded,

because defendant never having agreed to such imposition, it

may not be held a part of the compensation payable for holding

the land. The circumstance that defendant built a dwelling on

the agricultural lot does not ipso facto make it residential

considering specially that the dwelling photograph

submitted with brief does not occupy more than 80 square

meters occupied by him. In this connection, plaintiff argues as

follows:

The defendant does not till or cultivate the land in order to

grow the fruit bearing trees because they are already full

grown. He does not even do the actual gathering, and after

deducting the expenses, he gives one-half of the fruits to the

plaintiff all in consideration of his stay in the land. He is not,

therefore, a tenant within the meaning of that term as used in

Republic Act. No. 1199 for "A tenant shall mean a person who,

himself and with the aid available from within his immediate

farm household, cultivate the land for purposes of production .

. ."

Anyone who had fruit trees in his yard, will disagree with the

above description of the relationship. He knows the caretaker

must water the trees, even fertilize them for better production,

uproot weeds and turn the soil, sometimes fumigate to

eliminate plants pests, etc. Those chores obviously mean

"working or cultivating" the land. Besides, it seems that

defendant planted other crops, (i.e. cultivated the lot) giving

the landowner his corresponding share.

Now, the statutes provide that "All cases involving

dispossession of a tenant by the landholder . . . shall be under

the original and exclusive jurisdiction of such court as may

now or hereafter be authorized by law to take cognizance of

tenancy relations and disputes". Sec. 2, Republic Act 1199);

and the court (Agrarian Relations) "shall have original and

exclusive jurisdiction to consider, investigate, decide and settle

all questions and matters involving all those relationships

established by law which determine the varying rights of

persons in cultivation and use of agricultural land where one

of the parties works the land". (Sec. 7, Republic Act 1267 as

amended byRepublic Act 1409.)

In Tumbagan vs. Vasquez, L-8719, July 17, 1956, we impliedly

held that where a farmland occupies agricultural land and

4

erects a house thereon, the tenancy relationship continues

subject to tenancy laws not to those governing leases.

In fact, the Agricultural Tenancy Law (Republic Act

1199) requires the landholder to give his tenant an area

wherein the latter may construct his dwelling (sec. 26), of

course without thereby changing the nature of their

relationship, from landowner and tenant to lessor and lessee.

At any rate, this action must fail upon the second ground of

defendant's motion to dismiss: the plaintiff is a

mere apoderado of the owner, Severino P. Marcelo.

[[

1

]]

The rule

is that every action must be prosecuted in the name of the real

party in interest, (sec 2, Rule 3).

However, plaintiff quotes that part of sec. 1 of Rule 72,

permitting "the legal representative" of any landlord to bring an

action of ejectment, and insists in his right now to litigate.

Supposing that "legal representative" as used in sec. 1,

includes attorneys-in-fact, we find that plaintiff's power

attached to the complaint, authorizes him to sue for and in the

name of Severino Marcelo, to "pursue any and all kinds of

suits and actions for me and in my name in the courts of the

land". This action is not in the name of plaintiff's principal.

For all the foregoing, the appealed order is affirmed with costs

chargeable against appellant.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Supreme Court Second Division: PetitionerDokumen9 halamanSupreme Court Second Division: PetitionerGio HermosoBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial CaseDokumen7 halamanIndustrial CaseLoranisa BalorioBelum ada peringkat

- 024-Industrial Refractories Corporation of The Philippines vs. CA, Et Al G.R. No. 122174 October 3, 2002Dokumen5 halaman024-Industrial Refractories Corporation of The Philippines vs. CA, Et Al G.R. No. 122174 October 3, 2002Jopan SJBelum ada peringkat

- 7-Industrial Refractories Vs CA, SEC, Refractories CorpDokumen3 halaman7-Industrial Refractories Vs CA, SEC, Refractories Corpeunice demaclidBelum ada peringkat

- 024-Industrial Refractories Corporation of The Philippines vs. CA, Et Al G.R. No. 122174 October 3, 2002Dokumen5 halaman024-Industrial Refractories Corporation of The Philippines vs. CA, Et Al G.R. No. 122174 October 3, 2002wewBelum ada peringkat

- Com Rev: Chanrob1es Virtua1 1aw 1ibraryDokumen4 halamanCom Rev: Chanrob1es Virtua1 1aw 1ibraryJane Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial vs. CaDokumen4 halamanIndustrial vs. CaLenPalatanBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Refractories Corp of The Phil Vs CA: 122174: October 3, 2002: J. Austria-Martinez: SeDokumen6 halamanIndustrial Refractories Corp of The Phil Vs CA: 122174: October 3, 2002: J. Austria-Martinez: SeGen GrajoBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Refractories Vs CaDokumen5 halamanIndustrial Refractories Vs CaPhrexilyn PajarilloBelum ada peringkat

- SEC Ruling on Timeshare Purchase Agreement UpheldDokumen11 halamanSEC Ruling on Timeshare Purchase Agreement UpheldGeorginaBelum ada peringkat

- Cases IncorporationDokumen75 halamanCases IncorporationshakiraBelum ada peringkat

- SEC rules on confusingly similar corporate namesDokumen4 halamanSEC rules on confusingly similar corporate namesLalaine FelixBelum ada peringkat

- SEC Ruling on Timeshare Sale Appeal DismissalDokumen4 halamanSEC Ruling on Timeshare Sale Appeal DismissalJeah N MelocotonesBelum ada peringkat

- Timeshare Realty v. Lao, G.R. No. 158941Dokumen3 halamanTimeshare Realty v. Lao, G.R. No. 158941Rhenfacel ManlegroBelum ada peringkat

- Jetri Construction Corp Vs BPIDokumen6 halamanJetri Construction Corp Vs BPIMikey GoBelum ada peringkat

- J. Courtney Hixson For Petitioner. Thomas Cary Welch F or RespondentsDokumen7 halamanJ. Courtney Hixson For Petitioner. Thomas Cary Welch F or RespondentsKristine MagbojosBelum ada peringkat

- Shipside, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDokumen5 halamanShipside, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDaniel ValdezBelum ada peringkat

- General PrinciplesDokumen39 halamanGeneral PrinciplesJohn Paulo Say PetillaBelum ada peringkat

- Court rules on jurisdiction in contract dispute between Japanese firmsDokumen9 halamanCourt rules on jurisdiction in contract dispute between Japanese firmsKFBelum ada peringkat

- Rule 15 MotionsDokumen58 halamanRule 15 MotionsCentSeringBelum ada peringkat

- PropertyCases Art427Dokumen93 halamanPropertyCases Art427Melanie Joy Camarillo YsulatBelum ada peringkat

- Systems Factors v. NLRC - Art. 4 NCC (Prohibition On Retroactivity of Laws Exception)Dokumen3 halamanSystems Factors v. NLRC - Art. 4 NCC (Prohibition On Retroactivity of Laws Exception)Luke VerdaderoBelum ada peringkat

- AsdadadsasdadaaDokumen4 halamanAsdadadsasdadaaNurRjObeidatBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Supreme Court rules on jurisdiction in contract dispute between Japanese nationalsDokumen9 halamanPhilippine Supreme Court rules on jurisdiction in contract dispute between Japanese nationalsOneil SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Court Rules on Jurisdiction in Contract Dispute Between Japanese NationalsDokumen70 halamanCourt Rules on Jurisdiction in Contract Dispute Between Japanese NationalsOlek Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- KAZUHIRO HASEGAWA and NIPPON ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS CODokumen6 halamanKAZUHIRO HASEGAWA and NIPPON ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS COJeunaj LardizabalBelum ada peringkat

- Filoil Refinery Corp. v. MendozaDokumen4 halamanFiloil Refinery Corp. v. MendozaRodel Cadorniga Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- Hasegawa v. KitamuraDokumen7 halamanHasegawa v. KitamuraHaniyyah FtmBelum ada peringkat

- Jorge Gonzales v. Climax Mining Ltd.Dokumen3 halamanJorge Gonzales v. Climax Mining Ltd.shurreiBelum ada peringkat

- Jurisdiction of RTC over Cases Involving Title to Real PropertyDokumen275 halamanJurisdiction of RTC over Cases Involving Title to Real Propertymario navalezBelum ada peringkat

- Neypes vs CA Land Dispute Appeal DeadlineDokumen71 halamanNeypes vs CA Land Dispute Appeal DeadlineNiala AlmarioBelum ada peringkat

- 1 Ong Vs Mazo Case Digest OkDokumen7 halaman1 Ong Vs Mazo Case Digest OkIvan Montealegre ConchasBelum ada peringkat

- Civpro 1-28 Case DigestsDokumen33 halamanCivpro 1-28 Case DigestsPrincess Melody0% (1)

- HasegawaDokumen6 halamanHasegawaAnonymous qjsSkwFBelum ada peringkat

- 345843-2023-Uy v. 3tops de Philippines Estate Corp.20230214-12-Lg3ozyDokumen13 halaman345843-2023-Uy v. 3tops de Philippines Estate Corp.20230214-12-Lg3ozyTrady MarkgradyBelum ada peringkat

- 328 Bachrach V PPADokumen8 halaman328 Bachrach V PPAMlaBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 149177 November 23, 2007 Kazuhiro Hasegawa and Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., LTD., Petitioners, MINORU KITAMURA, RespondentDokumen14 halamanG.R. No. 149177 November 23, 2007 Kazuhiro Hasegawa and Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., LTD., Petitioners, MINORU KITAMURA, RespondentRalight BanBelum ada peringkat

- Lebin Vs MirasolDokumen12 halamanLebin Vs MirasolMelody May Omelan ArguellesBelum ada peringkat

- Bernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)Dokumen9 halamanBernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)eubelromBelum ada peringkat

- Perkin Vs Dakila Full CaseDokumen11 halamanPerkin Vs Dakila Full CaseNikkelle29Belum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 169067Dokumen6 halamanG.R. No. 169067Inter_vivosBelum ada peringkat

- Hasegawa vs. KitamuraDokumen7 halamanHasegawa vs. KitamuraIan Miranda Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Third DivisionDokumen6 halamanPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Third DivisionaifapnglnnBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence Digest Wa Pa NahumanDokumen26 halamanEvidence Digest Wa Pa NahumanChristineBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 180245 Case DigestDokumen3 halamanG.R. No. 180245 Case DigestMaricel SorianoBelum ada peringkat

- CD - 8. DFA v. BCA International Corp 2017Dokumen2 halamanCD - 8. DFA v. BCA International Corp 2017Czarina CidBelum ada peringkat

- Third Division: - VersusDokumen17 halamanThird Division: - VersusArthur John GarratonBelum ada peringkat

- Urgent Petition for Review of Orders Denying Motion to DismissDokumen17 halamanUrgent Petition for Review of Orders Denying Motion to DismissAkiBelum ada peringkat

- 2 113017-2005-PCI Leasing and Finance Inc. v. Emily Rose GoDokumen4 halaman2 113017-2005-PCI Leasing and Finance Inc. v. Emily Rose GoCamille CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Remedial Law CasesDokumen23 halamanRemedial Law Casesmonica may ramosBelum ada peringkat

- Enforcement of Liens - Lis PendensDokumen38 halamanEnforcement of Liens - Lis PendensKim EcarmaBelum ada peringkat

- Panay Railways V HevaDokumen5 halamanPanay Railways V HevaJade Palace TribezBelum ada peringkat

- Civpro Origs Week 1.1Dokumen105 halamanCivpro Origs Week 1.1CzarPaguioBelum ada peringkat

- C2 - Shipside Incorporated v. Court of AppealsDokumen4 halamanC2 - Shipside Incorporated v. Court of AppealsYe Seul DvngrcBelum ada peringkat

- Caiña, Et Al. vs. CA DIGESTDokumen10 halamanCaiña, Et Al. vs. CA DIGESTClaudine SumalinogBelum ada peringkat

- Panay Railways Vs HEVA ManagementDokumen2 halamanPanay Railways Vs HEVA ManagementMan-Man AcabBelum ada peringkat

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.Dari EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.Belum ada peringkat

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionDari EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionBelum ada peringkat

- The Letters of Gracchus on the East India QuestionDari EverandThe Letters of Gracchus on the East India QuestionBelum ada peringkat

- Patent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeDari EverandPatent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeBelum ada peringkat

- Tax CasesDokumen263 halamanTax CasesKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Civpro MTDDokumen18 halamanCivpro MTDKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Ra 10372Dokumen12 halamanRa 10372Jepski ScopeBelum ada peringkat

- Labor Trafficking and Illegal RecruitmentDokumen1 halamanLabor Trafficking and Illegal RecruitmentKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- No. L-29900 June 2Dokumen3 halamanNo. L-29900 June 2Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Sandiganbayan Presiding Justice Disqualification CaseDokumen20 halamanSandiganbayan Presiding Justice Disqualification CaseKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- CA Affirms Alegarbes' Ownership over Lot 140 through Acquisitive PrescriptionDokumen14 halamanCA Affirms Alegarbes' Ownership over Lot 140 through Acquisitive PrescriptionAnonymous m1TwEtt40Belum ada peringkat

- Ivler DigestDokumen2 halamanIvler DigestJette SalvacionBelum ada peringkat

- Cases For PrintingDokumen4 halamanCases For PrintingKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Coffee PartnersDokumen3 halamanCoffee PartnersMarivic Cheng EjercitoBelum ada peringkat

- JAVELLANADokumen21 halamanJAVELLANAKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Case 4Dokumen28 halamanCase 4Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Cases For Printing 2Dokumen4 halamanCases For Printing 2Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Anti-Cybercrime LawDokumen13 halamanAnti-Cybercrime LawMichael RitaBelum ada peringkat

- RA No. 349 and 7170Dokumen6 halamanRA No. 349 and 7170Jo JosonBelum ada peringkat

- STDokumen3 halamanSTKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Laurel VsDokumen5 halamanLaurel VsKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- NFSWDokumen8 halamanNFSWKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digests 2Dokumen4 halamanCase Digests 2Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Pantranco V PSCDokumen2 halamanPantranco V PSCKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Title: EadingDokumen1 halamanTitle: EadingKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Sales FullDokumen84 halamanSales FullKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Case 4Dokumen28 halamanCase 4Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Assign No. 1 Full CasesDokumen61 halamanAssign No. 1 Full CasesKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Cases 1Dokumen60 halamanCases 1Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- IncomeDokumen1 halamanIncomeKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Title: EadingDokumen1 halamanTitle: EadingKaren AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Mercantile Law 2013Dokumen4 halamanMercantile Law 2013Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Case 4Dokumen28 halamanCase 4Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment No.10Dokumen32 halamanAssignment No.10Karen AbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Registered Attachment Lien Superior to Earlier Unregistered DeedDokumen2 halamanRegistered Attachment Lien Superior to Earlier Unregistered DeedLei MorteraBelum ada peringkat

- 3-6.landbank of The Philippines vs. Honeycomb Farms Inc.Dokumen13 halaman3-6.landbank of The Philippines vs. Honeycomb Farms Inc.Mitch TinioBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Supreme Court upholds jurisdiction of labor department regional officesDokumen6 halamanPhilippine Supreme Court upholds jurisdiction of labor department regional officesDax MonteclarBelum ada peringkat

- Godrej and Boyce Manufacturing Co. Ltd. Vs. State of U.P. Case Analysis on Tax EvasionDokumen19 halamanGodrej and Boyce Manufacturing Co. Ltd. Vs. State of U.P. Case Analysis on Tax EvasionupendraBelum ada peringkat

- Civpro Case Digest PrefiDokumen17 halamanCivpro Case Digest PrefiNic NalpenBelum ada peringkat

- Surigao Century Sawmill, Co., Inc. V. Court of Appeals FactsDokumen2 halamanSurigao Century Sawmill, Co., Inc. V. Court of Appeals FactsAbdul-Hayya DitongcopunBelum ada peringkat

- GR NO 106615 January 15 2004Dokumen8 halamanGR NO 106615 January 15 2004coffeecupBelum ada peringkat

- Manuel Vs VillenaDokumen5 halamanManuel Vs VillenaregmorBelum ada peringkat

- Vios vs. Pantangco, Jr. - LEGTECHDokumen12 halamanVios vs. Pantangco, Jr. - LEGTECHJohnelle Ashley Baldoza TorresBelum ada peringkat

- Brief for National Assn of Reversionary Property Owners, National Cattlemen's Beef Assn, and Public Lands Council as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees and Urging Affirmance, Caquelin v. United States. No. 16-1663 (Dec. 28, 2016)-NCBA-PLC Amicus BriefDokumen200 halamanBrief for National Assn of Reversionary Property Owners, National Cattlemen's Beef Assn, and Public Lands Council as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees and Urging Affirmance, Caquelin v. United States. No. 16-1663 (Dec. 28, 2016)-NCBA-PLC Amicus BriefRHTBelum ada peringkat

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokumen3 halamanFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Labour Law Research ProjectDokumen37 halamanLabour Law Research ProjectRoshan ShakBelum ada peringkat

- ISRI Publication 2017Dokumen70 halamanISRI Publication 2017Florin Damaroiu50% (2)

- United States v. Dobbins, 4th Cir. (2010)Dokumen4 halamanUnited States v. Dobbins, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Law Report - Allahabad Series - Feb2010Dokumen152 halamanIndian Law Report - Allahabad Series - Feb2010PrasadBelum ada peringkat

- Rustan Pulp and Paper Mills v. IAC, 214 SCRA 665 (1992)Dokumen4 halamanRustan Pulp and Paper Mills v. IAC, 214 SCRA 665 (1992)Fides DamascoBelum ada peringkat

- Trademark Objection Refusals and Available RemediesDokumen3 halamanTrademark Objection Refusals and Available RemediesHarshita GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Mancenido VD CADokumen5 halamanMancenido VD CAmarvin magaipoBelum ada peringkat

- Dividing Matrimonial Assets and Determining Child Custody and Access in Singapore Divorce CaseDokumen32 halamanDividing Matrimonial Assets and Determining Child Custody and Access in Singapore Divorce Caselumin87Belum ada peringkat

- Form For Appeal To Appellate Authority: B. Sriman Narayana ReddyDokumen2 halamanForm For Appeal To Appellate Authority: B. Sriman Narayana ReddySamachara HakkuBelum ada peringkat

- Supreme CourtDokumen20 halamanSupreme CourtJan Nixon BallesterosBelum ada peringkat

- Cic Decisons ExemptnsDokumen35 halamanCic Decisons ExemptnsManuBelum ada peringkat

- State of HP and Anr V Ravinder Kumar and AnrDokumen10 halamanState of HP and Anr V Ravinder Kumar and AnrAditya SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Trial Court's Noncompliance With Procedural Rules Constitutes Grave Abuse of DiscretionDokumen8 halamanTrial Court's Noncompliance With Procedural Rules Constitutes Grave Abuse of DiscretionErnie Gultiano0% (1)

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds labor department decisions in Madrigal & Co. labor disputeDokumen136 halamanPhilippines Supreme Court upholds labor department decisions in Madrigal & Co. labor disputeSophiaKirs10Belum ada peringkat

- Condonation of Delay and Law of LimitationDokumen4 halamanCondonation of Delay and Law of LimitationVikramBhatiyaBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. L-41182-3 April 16, 1988 Dr. Carlos L. Sevilla and Lina O. Sevilla, PetitionersDokumen24 halamanG.R. No. L-41182-3 April 16, 1988 Dr. Carlos L. Sevilla and Lina O. Sevilla, PetitionersDiane JulianBelum ada peringkat

- Executive Programme (New Syllabus) Supplement FOR Tax LawsDokumen22 halamanExecutive Programme (New Syllabus) Supplement FOR Tax LawsShubham SarkarBelum ada peringkat

- 9th Cir Notice of AppealDokumen3 halaman9th Cir Notice of AppealSalam TekbaliBelum ada peringkat

- Sps. Miano vs. MERALCODokumen5 halamanSps. Miano vs. MERALCOAce GonzalesBelum ada peringkat