What Is The Role of Attachment

Diunggah oleh

Rommel Villaroman EstevesJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

What Is The Role of Attachment

Diunggah oleh

Rommel Villaroman EstevesHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

What is the Role of Attachment?

One of the most important items that any child carries with him is his relationship with

his primary caregiver. This person is usually his mother but may also be his father,

grandmother, or someone else entirely. This very first relationship is the basis for his

relationship with you.

What we know about early relationships really began with John Bowlby, whose ideas

are so much a part of our thinking today that its hard to imagine how revolutionary they

seemed just 50 years ago. While studying children who had been separated from their

parents at a young age, the British psychoanalyst came to believe that a babys

relationship with his closest caregivers plays a key role in development. Infants are

emotional beings who naturally form strong bonds with their parents, Bowlby

recognized, and the way those special adults interact with their baby wields a powerful

influence on how he turns out (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1969/1982).

Bowlby (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1969/1982) realized that human infants, like

other animal species, are born with instinctive behaviors that help them to survive. Acts

such as crying, smiling, vocalizing, grasping, and clinging keep babies close to their

primary caregivers, who protect them from predators, feed and soothe them, and teach

them about their environment. These attachment behaviors, as Bowlby (Ainsworth et

al., 1978; Bowlby, 1969/1982) called them, help to create attachmentchildrens vital

emotional tie to their primary caregiver or attachment figure. Nature equips attachment

figures with their own innate and complementary behaviorssoothing, calling,

restraining, for instancethat also serve to keep babies safe and cement the bond

between mother and child (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

In pioneering studies in the 1950s and 1960s, American psychologist Mary Ainsworth

(Ainsworth et al., 1978) confirmed Bowlbys theory by documenting for the first time the

emotional impact of parents everyday behavior on their children. In Uganda and then in

Baltimore, Ainsworth meticulously observed mothers and babies at home over the first

year of life. She watched the process of attachment unfold as the babies came to

recognize, prefer, seek out, and become attached to their primary caregiver.

These observations enabled Ainsworth to make a critical discovery: A babys sense of

security depends on how his attachment figure cares for him. During the first year of life

an infant evolves an attachment strategya way to organize feelings and behavior

that is tailor-made for coping with his own unique caregiving situation. The strategy he

develops is the one that will deal best with his particular stressful circumstances and

negative emotions and bring him the most security and comfort possible (van

IJzendoorn, Schuengel, and Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999; Weinfeld et al., 1999). All

attachment strategies are normal, adaptive, and functional; the trouble is that what

works best within the childs family may not work outside it (Greenberg, DeKlyen,

Speltz, and Endriga, 1997).

The Strange Situation

In Uganda, Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1978) observed that babies in unthreatening

situations used their mother as a secure base from which to explore their environment,

at ease as long as they could connect to her with a touch or a smile. When they felt

stressedif their mother left the room, for exampletheir attachment behaviors kicked

in and sent them searching for her reassurance. But in Baltimore, where mothers and

infants didnt spend as much time together, babies explored more freely and didnt

seem to mind when their mothers came and went. Did secure-base behavior exist in

North America, Ainsworth wondered? To find out, she devised the Strange Situation

(Ainsworth et al., 1978), a 20-minute laboratory procedure for 12-month-old babies and

their mothers that approximates real-life events. In eight short episodes, the mother

leaves and returns twice, gradually increasing the babys stress.

The procedure demonstrated that North American babies do indeed display secure-

base behavior, but it showed much more: The Strange Situation illuminated the whole

field of attachment by revealing two types of attachment that had not been apparent in

the home setting (Karen, 1998).

As Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1978) expected, babies who were securely

attached played comfortably with the toys in the laboratory, became upset

when their mother left, and greeted her eagerly on her return, warmly

accepting comfort from her.

But infants who were unhappy at homewho cried angrily, clung to their

mothers, and therefore seemed insecurely (or anxiously) attachedfell into

two distinct categories in the laboratory (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Weinfeld,

Sroufe, Egeland, and Carlson, 1999). Some stayed at their mothers side,

became extremely stressed when separated from her, wanted her when she

returnedbut cried or squirmed in her arms, resisting her soothing attempts.

Ainsworth labeled their attachment resistant or ambivalent. A second group of

babies seemed utterly blas in the lab. They played alone, didnt protest when

their mother departed, and paid no attention when she came back. Although

these infants looked secure and independent, Ainsworth knew from her home

observations that they were not. She termed them avoidantly attached.

In 1985, researchers Mary Main and Judith Solomon (1986) identified a fourth

group of infants who didnt fit into the three original categories. These babies,

who had what they called a disorganized/disoriented attachment, behaved

bizarrely in the Strange Situation, approaching their mothers backward, with

head averted, or in a trancelike state (Lyons-Ruth and Jacobvitz, 1999; Main

and Solomon, 1986).

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Strange Situation Procedure: Mary Ainsworth's (1971, 1978) Observational Study of Individual Differences inDokumen9 halamanStrange Situation Procedure: Mary Ainsworth's (1971, 1978) Observational Study of Individual Differences inelizaBelum ada peringkat

- Mary Ainsworth: Strange Situation ProcedureDokumen7 halamanMary Ainsworth: Strange Situation ProcedureDunea Andreea AnetaBelum ada peringkat

- Mary AinsworthDokumen7 halamanMary AinsworthfaniBelum ada peringkat

- Mary Ainsworth: Strange Situation ProcedureDokumen4 halamanMary Ainsworth: Strange Situation Proceduredudzkie angeloBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment and Loss Volumes. This Trilogy Brought ToDokumen1 halamanAttachment and Loss Volumes. This Trilogy Brought TojasonBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment TheoryDokumen6 halamanAttachment TheoryHarshaVardhanKBelum ada peringkat

- 2016 Apego Malaga PDFDokumen91 halaman2016 Apego Malaga PDFDavid BoixBelum ada peringkat

- SSPDokumen3 halamanSSPdiana.pocolBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment TheoryDokumen9 halamanAttachment TheoryJC BinangbangBelum ada peringkat

- Attaching in Differente WaysDokumen4 halamanAttaching in Differente WaysasistentevirtualdeyeiBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment PresentationDokumen58 halamanAttachment PresentationAiw88Belum ada peringkat

- Ways of AttachingDokumen4 halamanWays of AttachingasistentevirtualdeyeiBelum ada peringkat

- Joydeep Bhattacharya (MACP) Preethi Balan (PGDCP) Sanyogita Soni (PGDCP) Sutapa Choudhury (PGDCP)Dokumen20 halamanJoydeep Bhattacharya (MACP) Preethi Balan (PGDCP) Sanyogita Soni (PGDCP) Sutapa Choudhury (PGDCP)Tariq JaleesBelum ada peringkat

- Fonagy 1999Dokumen16 halamanFonagy 1999sfdkhkfjsfnsk njfsnksfnBelum ada peringkat

- Ttachment and Responsive ParentingDokumen23 halamanTtachment and Responsive ParentingGODEANU FLORINBelum ada peringkat

- Petters Attachment Theory and Artificial Cognitive Systems1Dokumen8 halamanPetters Attachment Theory and Artificial Cognitive Systems1jrwf53Belum ada peringkat

- Development of Attachment PDFDokumen15 halamanDevelopment of Attachment PDFArsalan AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Mary Ainsworth Theory A Strange Situation inDokumen4 halamanMary Ainsworth Theory A Strange Situation inzakiranzBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment TheoryDokumen41 halamanAttachment TheoryAngel MaeBelum ada peringkat

- Becoming Attached PDFDokumen18 halamanBecoming Attached PDFRoberto Montaño100% (4)

- Bowlby, The Strange Situation, and The Developmental NicheDokumen7 halamanBowlby, The Strange Situation, and The Developmental NicheVoog100% (2)

- Attachment Measures in ChildrenDokumen7 halamanAttachment Measures in ChildrenCentro C-RED 3HBelum ada peringkat

- Module 4 - Part 3 - SED 2100Dokumen15 halamanModule 4 - Part 3 - SED 2100kylieBelum ada peringkat

- Mary AinsworthDokumen13 halamanMary Ainsworthapi-356224906Belum ada peringkat

- AS Level Psychology EssayDokumen5 halamanAS Level Psychology EssaySandaluBelum ada peringkat

- Sroufe A Siegel D The Verdict Is in The Case For Attachment TheoryDokumen9 halamanSroufe A Siegel D The Verdict Is in The Case For Attachment TheoryAkshat AnandBelum ada peringkat

- The Verdict Is In: The Case For Attachment TheoryDokumen11 halamanThe Verdict Is In: The Case For Attachment TheoryELISA ANDRADEBelum ada peringkat

- The Organized Categories of Infant, Child, and Adult...Dokumen26 halamanThe Organized Categories of Infant, Child, and Adult...kingawitk100% (1)

- Mary AinsworthDokumen2 halamanMary Ainsworthtiana.vadell1858Belum ada peringkat

- Attachment ShitDokumen5 halamanAttachment ShitJohn PagangpangBelum ada peringkat

- Research, and Clinical Application (Pp. 649-670) - New York: Guilford PressDokumen61 halamanResearch, and Clinical Application (Pp. 649-670) - New York: Guilford PressEdu ArdoBelum ada peringkat

- Mary AinsworthDokumen2 halamanMary AinsworthMae Kris Sande Rapal100% (1)

- Dissmissive AttachmentDokumen19 halamanDissmissive AttachmentRobert WeathersBelum ada peringkat

- NBE3 English - CulminatingDokumen8 halamanNBE3 English - CulminatingsomedisappearingactBelum ada peringkat

- Articol Carla PinzaruDokumen21 halamanArticol Carla PinzaruMartha MEBelum ada peringkat

- Psych 250 Paper FinalDokumen8 halamanPsych 250 Paper Finalapi-546733227Belum ada peringkat

- The Work of Emmi PiklerDokumen8 halamanThe Work of Emmi PiklerRocsaineBelum ada peringkat

- Attatchment TheoryDokumen8 halamanAttatchment TheoryAgus BarretoBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment in Social DevelopmentDokumen18 halamanAttachment in Social DevelopmentRameen BabarBelum ada peringkat

- BabyhoodDokumen2 halamanBabyhoodJoyArianneOrtegaAdelBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment Contents of ChapterDokumen9 halamanAttachment Contents of ChapterRenis AsllaniBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1Dokumen10 halamanAssignment 1Jae StainsbyBelum ada peringkat

- Acceptance/responsiveness: Parenting StylesDokumen6 halamanAcceptance/responsiveness: Parenting Styleshoney torresBelum ada peringkat

- Twaters Medium PDFDokumen4 halamanTwaters Medium PDFTatianamotomotoBelum ada peringkat

- In Her Research in The 1970sDokumen3 halamanIn Her Research in The 1970srj lookyBelum ada peringkat

- Socialization and PersonalityDokumen5 halamanSocialization and PersonalitySage TuckerBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment Theory: Summary: Attachment Theory Emphasizes The Importance of A Secure and Trusting Mother-Infant BondDokumen3 halamanAttachment Theory: Summary: Attachment Theory Emphasizes The Importance of A Secure and Trusting Mother-Infant BondRessie Joy Catherine Felices100% (2)

- Your Primal Wound What Happened in ChildhoodDokumen5 halamanYour Primal Wound What Happened in ChildhoodYayo WashingtonBelum ada peringkat

- Devdeep Roy Chowdhury, M.SC, M.Phil Clinical PsychologistDokumen12 halamanDevdeep Roy Chowdhury, M.SC, M.Phil Clinical PsychologistDevdeep Roy ChowdhuryBelum ada peringkat

- PSY108 SU1 Nature-Nurture Controversy - Long Standing Dispute Over Relative Importance of Nature (Heredity)Dokumen43 halamanPSY108 SU1 Nature-Nurture Controversy - Long Standing Dispute Over Relative Importance of Nature (Heredity)Benjamin TanBelum ada peringkat

- Learning To Love: From Your Mother's Arms To Your Lover's ArmsDokumen4 halamanLearning To Love: From Your Mother's Arms To Your Lover's ArmsEva SunBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment Essay PlansDokumen13 halamanAttachment Essay Planstemioladeji04Belum ada peringkat

- Eportfolio-Finding FishDokumen10 halamanEportfolio-Finding Fishapi-23528676650% (2)

- 1271 The Verdict Is in PDFDokumen12 halaman1271 The Verdict Is in PDFinetwork2001Belum ada peringkat

- Recovering Reverie - Using Infant ObservationDokumen15 halamanRecovering Reverie - Using Infant ObservationCarla SantosBelum ada peringkat

- John Bowlby & Attachment - ppt2009Dokumen20 halamanJohn Bowlby & Attachment - ppt2009jolieoanaBelum ada peringkat

- AttachmentDokumen20 halamanAttachmentmrjaymsu2468Belum ada peringkat

- Attachment Theory in Relationships: Useful Tools to Increase Stability and Build Happy and Lasting Bonds. A Journey from Childhood to AdulthoodDari EverandAttachment Theory in Relationships: Useful Tools to Increase Stability and Build Happy and Lasting Bonds. A Journey from Childhood to AdulthoodBelum ada peringkat

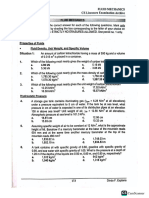

- 12 Vector AnalysisDokumen3 halaman12 Vector AnalysisRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 03 Plane GeometryDokumen13 halaman03 Plane GeometryRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 17 Geotechnical EngineeringDokumen45 halaman17 Geotechnical EngineeringRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 22 Steel DesignDokumen55 halaman22 Steel DesignRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 16 Fluid MechanicsDokumen29 halaman16 Fluid MechanicsRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 04 Solid GeometryDokumen15 halaman04 Solid GeometryRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 23 Timber DesignDokumen20 halaman23 Timber DesignRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 09 ProbabilityDokumen7 halaman09 ProbabilityRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 06 Differential CalculusDokumen19 halaman06 Differential CalculusRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 05 Analytic GeometryDokumen12 halaman05 Analytic GeometryRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 13 Engineering EconomyDokumen13 halaman13 Engineering EconomyRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- RCCRDokumen154 halamanRCCRRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 15 Transportation EngineeringDokumen5 halaman15 Transportation EngineeringRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 01 AlgebraDokumen23 halaman01 AlgebraRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 20 Theory of StructuresDokumen21 halaman20 Theory of StructuresRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 08 Differential EquationDokumen2 halaman08 Differential EquationRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 07 Integral CalculusDokumen12 halaman07 Integral CalculusRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 11 PhysicsDokumen6 halaman11 PhysicsRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 24 Construction Project ManagementDokumen19 halaman24 Construction Project ManagementRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Structural Analysis and Design: Owner: LocationDokumen14 halamanStructural Analysis and Design: Owner: LocationRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- What To Do When Cylinder Breaks Are LowDokumen3 halamanWhat To Do When Cylinder Breaks Are LowRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- 10 StatisticsDokumen1 halaman10 StatisticsRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Aponibolinayen and The SunDokumen7 halamanAponibolinayen and The SunRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- May Day EveDokumen7 halamanMay Day EveRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Social Development: Normal Patterns of Prosocial DevelopmentDokumen6 halamanSocial Development: Normal Patterns of Prosocial DevelopmentRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Qualities of TemperamentDokumen3 halamanQualities of TemperamentRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Variations in ParentingDokumen2 halamanVariations in ParentingRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Perspectives On DisciplineDokumen4 halamanPerspectives On DisciplineRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Setting A Good Example: Parents As Role ModelsDokumen3 halamanSetting A Good Example: Parents As Role ModelsRommel Villaroman Esteves100% (1)

- Sex EducationDokumen1 halamanSex EducationRommel Villaroman EstevesBelum ada peringkat

- Psychology As A Science of BehaviorDokumen72 halamanPsychology As A Science of BehaviorDr. Jayesh Patidar100% (2)

- Erik Erikson Psychosocial Stages of Development PDFDokumen2 halamanErik Erikson Psychosocial Stages of Development PDFJenniferBelum ada peringkat

- Educ 1 Chapter 4 PresentationDokumen42 halamanEduc 1 Chapter 4 PresentationKlarisse CruzadoBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge Child Care Centers 2013 0Dokumen11 halamanCambridge Child Care Centers 2013 0Santhosh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- ResearchDokumen7 halamanResearchNurul HudaBelum ada peringkat

- The Psychology of PlayDokumen12 halamanThe Psychology of PlaySuellen BaladoBelum ada peringkat

- Pedia Post Test 1Dokumen4 halamanPedia Post Test 1Mark Laurence Guilles100% (1)

- Erik EriksonDokumen16 halamanErik EriksonCathy RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Module 14 Socio Emotional Development Ofinfants and ToddlersDokumen49 halamanModule 14 Socio Emotional Development Ofinfants and ToddlersDARLENE CLAIRE ANDEZA100% (1)

- Pinakafinal Chapter1 in RMADokumen16 halamanPinakafinal Chapter1 in RMATeresa AdralesBelum ada peringkat

- Developmental Psychology Lecture NotesDokumen44 halamanDevelopmental Psychology Lecture NotesEva BeunkBelum ada peringkat

- Augusto - Discuss Ways in Which Communications Technology Can Help and Hinder Human Development Proceses. (HL)Dokumen3 halamanAugusto - Discuss Ways in Which Communications Technology Can Help and Hinder Human Development Proceses. (HL)Augusto de OliveiraBelum ada peringkat

- ED 152 Assignment Three Critcial Essay Semester 1 2017Dokumen8 halamanED 152 Assignment Three Critcial Essay Semester 1 2017Muzammil AbdulBelum ada peringkat

- Educ 101 ADokumen28 halamanEduc 101 AJohnver kenneth ApiladoBelum ada peringkat

- PSYDEVEDokumen4 halamanPSYDEVEJeri AlonzoBelum ada peringkat

- Adverse Childhood Experiences in School CounselingDokumen8 halamanAdverse Childhood Experiences in School Counselingapi-601189647Belum ada peringkat

- Quiz 4Dokumen2 halamanQuiz 4ALONSO PANDANABelum ada peringkat

- Prelim Exam CADDokumen3 halamanPrelim Exam CADDivyne BonaventeBelum ada peringkat

- Falcte Prelim To FinalsDokumen42 halamanFalcte Prelim To FinalsBrigette Habac100% (1)

- Human Growth and DevelopmentDokumen64 halamanHuman Growth and DevelopmentmargauxeBelum ada peringkat

- Developmental Screening TestDokumen23 halamanDevelopmental Screening TestSheron MathewBelum ada peringkat

- Paper II TM (SS) Code 51 Session 1 Set G 25.02.2018 PDFDokumen64 halamanPaper II TM (SS) Code 51 Session 1 Set G 25.02.2018 PDFThanmayeesaisowmya SunkaraBelum ada peringkat

- Psychological Development of ShameDokumen5 halamanPsychological Development of Shamejamie v100% (1)

- Bronfenbrenner's Ecological SystemDokumen4 halamanBronfenbrenner's Ecological SystemAngel Capaciete100% (1)

- Early Childhood Development - Chapter Three (Trawick-Smith) 2014Dokumen75 halamanEarly Childhood Development - Chapter Three (Trawick-Smith) 2014Rodney Moore67% (3)

- Child Development: Ma'am Kathrine PelagioDokumen13 halamanChild Development: Ma'am Kathrine PelagioJhaga Potpot100% (1)

- Lesson 2 ReviewerDokumen10 halamanLesson 2 ReviewerFerlynne Marie BernardinoBelum ada peringkat

- Attachment in AdolescenceDokumen17 halamanAttachment in AdolescenceMário Jorge100% (1)

- Professional Reading Report PDFDokumen7 halamanProfessional Reading Report PDFRenan RoqueBelum ada peringkat

- Free Online Psychology CoursesDokumen7 halamanFree Online Psychology CoursesMr.READERBelum ada peringkat