A Retro Version' of Power. Agamben Via Foucault On Sovereignty

Diunggah oleh

Jaewon Lee0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

38 tayangan17 halaman'Retro-version' of Power: Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty by Peter Gratton. Opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor and Francis. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden

Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

A ‘Retro‐Version’ of Power. Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Ini'Retro-version' of Power: Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty by Peter Gratton. Opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor and Francis. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

38 tayangan17 halamanA Retro Version' of Power. Agamben Via Foucault On Sovereignty

Diunggah oleh

Jaewon Lee'Retro-version' of Power: Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty by Peter Gratton. Opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor and Francis. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 17

This article was downloaded by: [Chung Ang University]

On: 27 July 2014, At: 19:58

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,

UK

Critical Review of International

Social and Political Philosophy

Publication details, including instructions for authors

and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcri20

A Retroversion of Power:

Agamben via Foucault on

Sovereignty

Peter Gratton

a

a

Chicago, IL, USA

Published online: 21 Nov 2006.

To cite this article: Peter Gratton (2006) A Retroversion of Power: Agamben via

Foucault on Sovereignty, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy,

9:3, 445-459

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13698230600901238

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the

information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform.

However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or

suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed

in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the

views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should

not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions,

claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities

whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection

with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.

Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-

licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy

Vol. 9, No. 3, 445459, September 2006

ISSN 1369-8230 Print/1743-8772 Online/06/030445-15 2006 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/13698230600901238

A Retro-version of Power:

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

PETER GRATTON

Chicago, IL, USA

Taylor and Francis Ltd FCRI_A_190043.sgm 10.1080/13698230600901238 Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 1369-8230 Print/1743-8772 Online Original Article 2006 Taylor & Francis 93000000September 2006 PeterGratton p.gratton@comcast.net

A

BSTRACT

This essay reviews Agambens work on the sovereign exception to ask whether it

has missed crucial aspects in its reading of Foucault, especially given Foucaults worry that

the focus in political theory on sovereignty was but a focus on a retro-version of power. The

first part reviews Foucaults work on power and sovereignty in

The History of Sexuality

and

ancillary texts from the late 1970s and early 1980s, followed by Agambens work on sover-

eignty and its connection to the work of Foucault. The essay is less concerned with whether

Agamben is faithful to the work of Foucault than in ascertaining if Agamben forms a critique

of sovereignty in line with what Foucault would consider a nave notion of power, or if

Agamben has identified something about the very concept of sovereignty, its place as excep-

tion to law and history, that is missing from Foucaults analysis.

K

EY

W

ORDS

: Foucault, Agamben, sovereignty, power

Even today [without formal royalty], democracy has not profoundly displaced

this schema [of sovereignty]; it has only supposed or repressed it Like what

is repressed, then, the schema of the sovereign exception never stops returning.

(Nancy 2000)

Political theory has never ceased to be obsessed with the person of the

sovereign. We need to cut off the kings head: in political theory, that has

yet to be done. (Foucault 1980)

There is little doubt that, at least within the recent literature, sovereignty and its

reconceptualization, along the lines of Karl Schmitts work on the sovereign excep-

tion, has made a return, as Nancy suggests, if indeed it has ever left the way in which

the political has been thought. Giorgio Agambens recent work, for example in

Homo Sacer

and

State of Exception

, has been exemplary of this rethinking, offering

a compelling analysis of the history of the political as practiced in the West as the

Correspondence Address:

2444 W. Sunnyside Avenue No. 1, Chicago, IL 60625, USA. Email:

p.gratton@comcast.net

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

446

P. Gratton

continual repetition of the

ban

, the inclusion/exclusion of what he calls bare life

an inclusion/exclusion that is the very effect of the sovereign decision against

which the political life is directed and constituted. What interests me here what

should be of interest to all those attempting to rethink sovereignty is whether

contemporary work on this concept suffers from a nave view of power identified

well in the first volume of

The History of Sexuality

: power operates along a line of

force that is always vertical, in a state-form, even if that state form is a state of

emergency discussed in Walter Benjamins Theses on the Philosophy of History

(Benjamin 1969: 257). One need not accept the whole of Foucaults work on power

to agree that power operates through the very movement of discourse (whether

political, psychological, historical or otherwise) and is polyvalent and polymorphic;

power is irreducible to the state apparatus. At the risk of falling into tautology, this is

what makes power powerful. In any event, the question of the polymorphism of

power is an apt one to put to Agamben in particular: it is in his work, rather than in

Derrida, Nancy, Chantal Mouffe and others, where one finds so many explicit

references to Foucault, especially the latters work on bio-power. My question is

whether Agamben has replaced Foucaults avowed regicide of power with an

emptied-out concept of sovereignty that nevertheless acts as a place-holder for a

reinsertion of a vertical conception of power whose crystallization, Foucault

believed, was the

result

, rather than the driving element, of the network of power

relationships operating in a society at a given time.

In the first part of this essay, I will review Foucaults work on power and sover-

eignty in

The History of Sexuality

and ancillary texts from the late 1970s and early

1980s. From here, I will quickly review Agambens work on sovereignty and its

connection to the work of Foucault. I am less interested in whether Agamben is

faithful to the work of Foucault than in ascertaining if Agamben forms a critique of

sovereignty in line with what Foucault would consider a nave notion of power, or if

Agamben has identified something about the very concept of sovereignty, its place

as exception to law and history, that is missing from Foucaults analysis. This may

seem to come down to whether sovereignty is

merely

a concept that escapes a

certain historicity (Agamben) or whether it has a certain historical unfolding

(Foucault). I will discard these possibilities: things are not so simple with either

writer, and their work is not reducible to either conceptual or historicist approaches.

This will become clear as we move along.

I

The contours of Foucaults main argument in

The History of Sexuality

are well

known. Foucault begins and ends this work by critiquing the reductionist view of

power despite the title of the work, it is less a treatise on sexuality than the

practices of power during the last two hundred years found in what Foucault terms

the repressive hypothesis. This hypothesis, Foucault writes, is not just simplistic but

works hand-in-glove with the rise of a regime of power-knowledge that it says it

critiques. The repressive hypothesis is based on a conflation of power with rules and

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

447

laws.

1

The history of sexuality under the repressive hypothesis is nothing other than

the silencing and censoring by authorities of perverted sexualities that threaten

(depending on the particular ideological approach) either the moral order or

economic capitalism. This view sees power as stable and coherent and thus escap-

able. As such, believers in the repressive hypothesis paint a portrait of the nineteenth

and early twentieth century, according to Foucault, against the backdrop of a poten-

tial liberation from this repression, a liberation already underway in the practices

and theories of the no-longer-repressed other Victorians. Notably, the repressive

hypothesis of society is but a cultural analogue to a long line of thinking in political

theory that has conflated power with law, that is, power as a negative element that

dictates only that which

cannot

be done under a given regime.

Foucaults objective in

The History of Sexuality

, he writes, is to analyze sexuality

not in terms of repression or law, but in terms of power. (Note that Foucault here

opposes power to law; later in

The History of Sexuality

, he will argue that the latter

is but the crystallization of various forms of power relations in a given society.

That is, it both refracts all other power relations at the same time that it solidifies the

power relations of a given period.) For Foucault, power is not a group of institu-

tions and mechanisms that ensure the subservience of the citizens of a given state,

or a mode of subjugation, which in contrast to violence, has the form of the rule

(Foucault 1978: 92). More pointedly, Foucault argues that power

is not a general system of domination exerted by one group over another, a

system whose effects pervade the entire social body. The analysis, made in

terms of power, must not assume that the sovereignty of the state, the form of

the law, or the over-all unity of a domination are a given at the outset; rather

these are only terminal forms power takes. [Thus power] must not be sought

in the primary existence of a central point, in a unique source of sovereignty

from which secondary and descendant forms would emanate. (Foucault 1978:

9293)

Foucault is critical of any discourse that assumes the performance of a sovereign,

even the sovereign-father of psychoanalysis (Foucault 1978: 150); power is always

decentered, a moving substrate of force relations which, by virtue of their inequal-

ity, constantly engender states of power that are nevertheless local and unstable

(Foucault 1978: 92). We move, then, in Foucault, from a grand-narrative of power

to a micro-politics engaged in analyzing the complex strategical situation in a

particular society (Foucault 1978: 93).

Foucault sets forth a number of propositions with regard to power: (1) it is not the

property of an agent, but is exercised from innumerable points, in the interplay of

non-egalitarian and mobile relations (Foucault 1978: 94); (2) though de-centered

from any subject, power is intentional, always operating strategically through a

series of aims and objectives (Foucault 1978: 95); and (3) relations of power are

immanent to all social relations (economic, scientific, pedagogic, sexual and so

forth). Power, thus, is irreducible to any entity or agent including, significantly,

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

448

P. Gratton

though he doesnt mention it, the sovereign since power

comes from below

all

the way to the major dominations (emphasis added). The state, in sum, is nothing

other than an effect of power relations already at work in the discursive formations

of a given society (Foucault 1978: 94). We must, he writes, orient ourselves

toward a conception of power that

replaces the privilege of law with the view point of the objective, the privilege

of prohibition [as in the repressive hypothesis] with the viewpoint of tactical

efficacy, the privilege of sovereignty with the analysis of a multiple and mobile

field of force relations. The strategical model, rather than the model based on

law. (Foucault 1978: 102)

This must points us towards an ethics underway in Foucaults discussion of power:

we must rethink power not simply as a means of furthering theoretical practices,

but because of the affects of unequal power relations scattered across society. Two

further points are important: First, it appears that Foucault conflates sovereignty

with the functioning of the law, rather than recognizing that the very concept of

sovereignty puts it above or outside the law, as Agamben notes. The history of

liberal thought since Hobbes has been nothing other than an attempt to circumscribe

the sovereign exception within the rule of law, a theoretical challenge that has

largely failed thus the habitual return of the repressed noted by Nancy and the

opening provided to interventions such as those provided by Agamben. Secondly,

Foucault is also only calling into question the privileging of one model over the

other; he is not necessarily arguing that one phase (the phase of sovereignty) has

been superceded

in toto

. In his essay, Governmentality, for example, Foucault

argues that

We need to see things not in terms of the replacement of a society of sovereignty

by a disciplinary society and the subsequent replacement of a disciplinary soci-

ety by a society of government; in reality one has a triangle, sovereignty-disci-

pline-government, which has as its primary target the population and as its

essential mechanism the apparatuses of security. (Foucault 1994: 219)

Foucault is less than clear, writing three years after the publication of the first

volume of

The History of Sexuality

, about what this diagrammatic consideration of

sovereignty means. What is clear, though, is that the polymorphic power he identi-

fies in

The History of Sexuality

is a new phase in history. Here, Foucault argues that

there is indeed a move from the type of power demonstrated during the classical age

(via the sovereign and the rule of law) and the polymorphic operations of power in

the contemporary period.

2

It would seem, then, that the proponents of the repressive

hypothesis are engaged less in putting forth a nave view of power than describing a

functioning of power that is

pass

. For example, psychoanalysis, Foucault argues,

by theorizing sexuality in terms of the law, the symbolic order, and sovereignty,

attempted, in the first decades of the twentieth century to surround desire with all

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

449

the trappings of the

old order of power

(Foucault 1978: 150, emphasis added). The

version of the history of sexuality on offer from psychoanalysis, or even the ques-

tioning of sovereignty in Bataille, is, Foucault writes, in the last analysis a histori-

cal

retro-version

. We must conceptualize the deployment of sexuality on the

basis of the techniques of power that are

contemporary

with it (1978: 150, empha-

sis added). Or, as he puts it a 1976 lecture,

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, we have the production of an

important phenomenon, the emergence, or rather the

invention

, of a

new

mechanism of power possessed of highly specific strategical techniques

absolutely incompatible with the relations of sovereignty This new type of

power

can no longer be formulated

in terms of sovereignty.

3

(Foucault

1980: 104105)

In fact, Foucault argues that retro-versionist theories of sovereignty

allow a system of right to be superimposed upon the mechanisms of discipline

in such a way as to conceal its [disciplines] procedures, the element of

domination inherent in its techniques, and to guarantee to everyone, by virtue

of the sovereignty of state, the exercise of his [or her] proper sovereign rights.

(Foucault 1980: 105)

As such, if sovereignty has survived as a discourse of its own into the twentieth (and

twenty-first) centuries, embedded in the legal codes of the West, it is only as a ruse

diverting attention from, and concealing from view, the disciplining of the body,

of life, taking place by means and devices of power heterogeneous to the

mechanisms of sovereignty. Foucault argues, it is the emergence of

population

as a

political term, that is, of bio-power (linked explicitly by Agamben to the sovereign

decision), which was the death of the regime of power associated with sovereignty

(Foucault 1994: 216). Retro-versions of sovereignty, for Foucault, reinforce rather

than resist these particular power formations; they preclude the analysis necessary

for such resistance (Foucault 1980: 187). Or, to put it even more succinctly,

Foucault writes, you no longer have a sovereign right that is in excess of biopower,

but a biopower that is in excess of sovereign right This formidable extension of

biopower will put it beyond all human sovereignty, that is to say, individual

mastery (Foucault 2004: 254).

This may be why, as we noted above, that Foucault argues in 1978 that power

continues to operate within a triangle (sovereigntydisciplinegovernment) that

includes, but is not dominated by, sovereignty. The latter operates, it seems, not

because it is dominant over a particular phase of society that recognizes its rights

over life and death. Rather, while no longer

the

locus of power, sovereignty haunts

(Foucault 1994: 187) the thinking of power to such a degree that, as a cover for the

regimes of discipline, it is, practically speaking, a point of relation within which

power moves in the contemporary period.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

450

P. Gratton

Let us quickly revisit the last chapter of

The History of Sexuality

, since this is

what Foucault calls the fundamental part of the book and will provide no small

amount of influence on Agamben. We will retrace, briefly, the genealogy of power

from a regime of sovereignty to the society of discipline and surveillance, the soci-

ety of bio-power, in the modern period. For a long time, one of the characteristic

privileges of sovereign power, Foucault begins the chapter, was the right to decide

life and death. Derived from the Roman

patria potestas

, which granted the father

the right to dispose of his children and slaves, sovereignty in the classical age was

redefined in a considerably diminished form as an ability to exercise power only

in the cases where the sovereigns very existence was in jeopardy (Foucault 1978:

135). Foucault does not develop here what both Schmitt and Agamben will note

about this peculiarity of sovereignty: it is the sovereign itself that dictates those

cases in which it is in jeopardy, operating as such outside the law in order to ensure

the effectiveness of the law; sovereignty as such never appears, pace Foucault, in a

diminished form. This is the sovereign exception. In any event, this power is

dubbed by Foucault conditional, for use only when the sovereigns very life is at

stake. The symbol of sovereignty was the sword,

4

Foucault remarks, and one can see

its example, he could note, in the depiction of Hobbess state on the cover of the

Leviathans

first editions. Power in a society governed by the sovereign is exer-

cised mainly as a means of deduction (

prlvement

), a subtraction mechanism

Power in this instance was essentially a right of seizure: of things, time, bodies, and

ultimately life itself; it culminated in the privilege to seize hold of life in order to

suppress it (Foucault 1978: 136).

In the contemporary period, power, Foucault believes, metastasizes itself through

an administration of life, in the name of the security and safety of populations. What

is at stake in this power is no longer the juridical existence of sovereignty; at stake

is the biological existence of a population, not a people. Power is situated and

exercised at the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of

race (Foucault 1978: 137). Thus sexuality is an exemplary point through which it

operates, given the nexus of life and death, of population control, at stake in its

movement.

It is in the classical period that one form of power began to supplant the other.

During the classical period, the problems of birthrate, longevity, and public health in

general became the province of the power. Hence, Foucault writes, there was an

explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of

bodies and the control of populations, marking the beginning of the era of bio-

power. The latter was an important element in the rise of capitalism (N.B., not

vice-versa, for Foucault) and what Foucault calls the entry of life into history, that

is, the entry of phenomena peculiar to the life of human species into the order of

knowledge and power, into the sphere of political techniques. In short, methods of

power and knowledge assumed responsibility for the life processes and undertook to

control and modify them. For the first time in history, no doubt, biological exist-

ence was reflected in political existence (Foucault 1978: 142). Another conse-

quence, Foucault writes,

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

451

was the growing importance assumed by the action of the norm, at the

expense of juridical system of the law A power whose task it is to take

charge of life needs continuous regulatory and corrective mechanisms. It is

not longer a matter of bringing death into play in the field of sovereignty, but

of distributing the living in the domain of value and utility The law

operates more and more as a norm, and the judicial institution is increas-

ingly incorporated into a continuum of apparatuses (medical, administrative,

and so on) whose functions are, for the most part, regulatory. A normalizing

society is the historical outcome of a technology of power centered on life.

(Foucault 1978: 144)

In order words, bare life, as Agamben will call it, became included into the very

administration of the political itself. The

telos

of this thought, Agamben will say, is

nothing other than genocide and holocaust, and Foucault argues himself that bio-

power has given rise to the racist state.

5

Foucault concludes, in words oft-quoted by

Agamben:

For millennia, man remained what he was for Aristotle: a living animal with

the additional capacity for political existence; modern man is an animal whose

politics places his existence as a living being in question [in the double sense:

as a problem and as a threat]. (Foucault 1978: 143)

Thus, if philosophy begins with Socrates dictum that the unexamined life is not

worth living, for Foucault, modern power begins with the dictum that the unexam-

ined life, the undisciplined life, is not just death, but a threat to distributions around

the norm, to power itself (Foucault 1978: 144).

II

In

Homo Sacer

and related works over the past ten years, Agamben argues that the

original political relation is the

ban

, in which a particular mode of life is excluded

(and thus, by a certain logic, included) from the

polis

. Although it is unclear in

Agambens work whether the

ban

is a particularly modern phenomena, as it is in

Foucaults work, or has always already been at work in the politics of the West, it is

clear that the conditions for the possibility of the

ban

are co-extensive with Western

metaphysics. Whereas Foucaults analysis is historical, or better, genealogical,

Agambens work on the bio-political is often conceptual, which is what makes his

forays into concrete examples (e.g., the

Muselmnner

of the Nazi death camps) both

helpful to understanding his theory and often, well, infuriating, since Agamben

often piles on generalization after generalization about Western metaphysics in

books notable for essays short in length and broad in scope before arriving at the

claim that the death camps are not, contra Arendt, anti-political (since they lacked

any plurality or public space), but the apotheosis of the political itself, as least as it

has been dreamed of in the West.

6

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

452

P. Gratton

For all of his influences (Schmitt, Derrida, Nancy, Foucault, Heidegger and

Benjamin) and the breadth of references coming in his texts in quick order (from

Aristotle to Heidegger to Roman law), the force of Agambens work is its interven-

tion in the space left behind by Foucault.

Homo Sacer

begins and ends, notably,

with references to Foucault, and the whole of Agambens work on the political

converges on his quest to accomplish what he believes Foucault failed to do: iden-

tify the heretofore hidden point of intersection between the juridico-institutional

and the bio-political models of power (Agamben 1998: 6). Let me quote at length

from Agamben on this point:

If Foucault contests the traditional approach to the problem of power, which is

exclusively based on juridical models (What legitimates power?) or on

institutional models (What is the State?), and if he calls for a liberation from

the theoretical privilege of sovereignty in order to construct an analytic of

power that would not take law as its model and code, then where, in the body

of power, is the zone of indistinction (or, at least, the point of intersection) at

which technologies of individualization and totalizing procedures converge?

And, more generally, is there a unitary center in which the political double

bind finds its reason to be? What is the point at which the voluntary

servitude of individuals comes into contact with objective power?

Confronted with phenomena such as the power of the society of the spectacle

that is everywhere transforming the political realm today, is it legitimate or

even possible to hold subjective technologies and political technologies apart?

The present inquiry concerns precisely this hidden point of intersection

between the juridico-institutional and the biopolitical models of power.

(Agamben 1998: 56; repeated almost verbatim at 119)

The nucleus of this zone of indistinction is sovereignty: It can even be said, Agam-

ben writes, that the production of a biopolitical body is the original activity of sover-

eign power (Agamben 1998: 6). Bare life is produced in and through the fundamental

act of sovereignty deciding upon who is and who is not to be granted status in the

state and thus is politicized by the sovereigns very act of exclusion. For Carl

Schmitt, the exception is related directly to the state of emergency, a situation

(economic or political) that threatens the state and requires the sovereign to act

outside the law in order to protect the very continuance of those laws. But since it is

the sovereign who decides whether this crisis exists, and since this crisis is always

one that is extra-constitutional, no law can ever anticipate, that is to say limit, the

sovereign in advance. Sovereignty is nothing other than this monopoly over this deci-

sion, a decision, ultimately, over the distinction between friend and enemy, the funda-

mental political distinction for Schmitt. The political enemy, Schmitt writes, is

the other, the stranger; and it is sufficient for his nature that he is, in a specially

intense way, existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme

case conflicts with him are possible. These can neither be decided by a previous

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

453

determined general norm nor by the judgment of a disinterested and neutral

party. (Schmitt 1996: 27)

This is the crux of Schmitts attack on liberalism in general, namely, that in the

name of the rule of law, the openness of discussion of parliaments and congresses, it

has obscured the fundamental political distinction that makes such laws possible in

the first place: the friend-enemy distinction. In other words, where liberals see the

state as the meeting ground for consensus and cautious half-measures, Schmitt

sees only the stabilized results of a conflict that brought a people into being in the

first place (Schmitt 2006: 63). The state is not simply a facilitator of open discus-

sions among disparate groups, or an administrator of economic goods for society; it

is primarily a means for internal order such that a proper relation of enmity with

other peoples can be constituted. The normal order that liberalism takes for

granted is nothing other than the result of an originary and instituting violence of the

state of exception, which returns at each moment that the constitutional order is

threatened: every legal order is based upon a decision (Schmitt 2006: 6).

It really does not matter whether an abstract scheme advanced to define

sovereignty (namely, that sovereignty is the highest power, not a derived

power) is acceptable What is argued about is the concrete application, and

that means who decides in a situation of conflict what constitutes the public

interest or interest of the state, public safety and order,

le salut public

, and so

on. The exception, which is not codified in the existing legal order, can at best

be characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the

state, or the like. But it cannot be circumscribed factually and made to conform

to a preformed law. (Schmitt 2006: 6)

Or, to put it succinctly, sovereign is he who decides on the exception (Schmitt

2006: 6). For Schmitt, it is clear, too, that he means for these moments of exception

to be temporary. Despite its placement outside the law, this sovereign decision is not

arbitrary, since it keeps in place the very normalcy that prevents a slide into utter

chaos;

le salut public

is thus both an (ostensibly temporary) good-bye to the public

space and its saving grace.

What characterizes an exception is principally unlimited authority, which means

the suspension of the entire existing order. In such a situation it is clear that the

state remains, whereas law recedes. Because the exception is different from anar-

chy and chaos, order in the juristic sense still prevails even if it is not of the ordi-

nary kind. The existence of the state is undoubted proof of its superiority over the

validity of the legal norm. The decision frees itself from all normative ties and

becomes in the true sense absolute. The state suspends the law in the exception

on the basis of its right of self-preservation, as one would say (Schmitt 2006: 12).

We could spend an entire essay following the turns of this circular reasoning, of

the foundationless fiction of the right of self-preservation sovereignty operates,

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

454

P. Gratton

Schmitt writes, exceptional to any norm, any right, and any law--based on nothing

other than an appeal what everyone knows: as one would say.

As Agamben reads Schmitt, the sovereign exception is the decision over the very

relation between law and fact, or, to put it another way (and to show the breadth of

Agambens analysis), the interpretive leap between the universal and particular that

is the province of all judgments, juridical and otherwise. The sovereign structure of

the law, its peculiar and original force has the form of a state of exception in which

fact and law are indistinguishable (yet must, nevertheless, be decided on)

(Agamben 1998: 27). This power of the sovereign is always potential, for the sover-

eign never exhausts itself in its actual use of power (Agamben 1998: 1819).

Bare life is produced in and through the fundamental act of sovereignty deciding

upon who is and who is not to be granted status in the state and thus is politicized

by the sovereigns very act of exclusion. For Carl Schmitt, the exception is related

directly to the state of emergency, a situation (economic or political) that threatens

the state and requires the sovereign to act outside the law in order to protect the very

continuance of those laws. But since it is the sovereign who decides whether this

crisis exists, and since this crisis is always one that is extra-constitutional, no law can

ever anticipate, that is to say limit, the sovereign in advance. Sovereignty is nothing

other than this monopoly over this decision, a decision, ultimately, over the distinc-

tion between friend and enemy, that is, the fundamental political distinction for

Schmitt (Schmitt 1996: 2227). As Agamben reads Schmitt, the sovereign exception

is the decision over the very relation between law and fact. The sovereign structure

of the law, its peculiar and original force has the form of a state of exception in which

fact and law are indistinguishable (yet must, nevertheless, be decided on) (Agamben

1998: 27). And this power of the sovereign is always

potential

, for the sovereign

never exhausts itself in its actual use of power (Agamben 1998: 1819).

As such, bare life has entered the

polis

to such an extent that all life, for the sover-

eign, has been reduced to bare life in the states of emergency making states of

emergency zones of indistinction between nature (

physis

) and law (

nomos

),

z

[ emacr ]

and

bios

(Agamben 1998: 64):

If the exception is the structure of sovereignty, then sovereignty is not an exclu-

sively political concept, and exclusively juridical category, a power external to

law (Schmitt), or the supreme category of the juridical order (Hans Kelsen): it

is the originary structure in which law refers to life and includes it in itself by

suspending it The relation of exception is a relation of ban. He who has been

banned is not in fact, simply set outside the laws and made indifferent to it but

rather

abandoned

by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in

which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguishable. It is literally

not possible to say whether one who has been banned is outside or inside the

juridical order. (Agamben 1998: 2829)

It follows from all of this that biopolitics is at least as old as the sovereign excep-

tion. That is to say, wherever there is the sovereign exception (and Agamben will

oe

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty

455

date this exception all the way back to Aristotle (Agamben 1998: 27)), there is

biopolitics. Agambens contention, though he doesnt state it explicitly, is a reversal

of Foucaults claims with regard to sovereignty.

Two problems arise immediately. First, if, as Agamben argues, the problem of

bare life dates at least to the diffentiation of

z

[ emacr ]

(bare life) and

bios

(the life partic-

ular to the

polis

) in Aristotles

Politics

(Agamben 1998: 13, 98101), then why is it

a particularly modern movement that sees the politicization of bare life and the

entry of

z

[ emacr ]

into the

polis

? How is it the modern event

par excellence

? What

makes the bio-political (and the sovereignty that is its link to the juridical-institu-

tional) the metaphysical task

par excellence

and

modern? Secondly, and related to

this, is Agambens attempt to bridge these two claims. The modern event of the

entry of

z

[ emacr ]

into the

polis

occurred by a declaration of modernitys own faithful-

ness to the essential structure of the metaphysical tradition. Did the sovereigns of

early modernity suddenly read Aristotle? Did these would-be philosopher kings

bring out, de-conceal, what philosophy always wanted at its very core? This point is

at once glib and important. Agambens work is rife with metaphors of concealment

and de-concealment, a debt owed to his work on Martin Heidegger. Early modernity

only brought to light, he says, the secret unity between power and bare life in the

exercise of sovereignty, and it is only inevitable that this biopolitics operates,

though concealed, within metaphysics itself (Agamben 1998: 122). All this as bio-

power secretly governs modern ideologies of the left and the right (a view that

Foucault also shared, though Foucaults analysis is not as apocalyptic as Agam-

bens). Uncovering these secret and hidden collusions is what is necessary in the

face of the

telos

of Western metaphysics. Only this de-concealing can save us

from the more and more bio-politicization, that is the increasing dominance of

the state of exception (Agamben 2005: 2), as it returns philosophy to its practical

calling (Agamben 1998: 6). This would be nothing other than the discovery, a

bringing to light, of a new politics no longer founded in the

exceptio

of bare

life (Agamben 1998: 11). A classic messianism.

Leaving this aside, Agamben is correct to point to a deeper consideration of the

exception of sovereignty necessary in thinking the political. And it is true that

Foucaults modes of resistance in his texts of the early 1980s, in terms of pleasures

of the body, can appear isolated from the problems of the states of exception. Agam-

ben concludes his book with a consideration of Foucaults work (and Ill quote one

last time at length):

At the end of the first volume of the

History of Sexuality

, having distanced

himself from the sex and sexuality in which modernity, caught in nothing other

than a deployment of power, believed it would find its own secret and libera-

tion, Foucault alludes to a different economy of bodies and pleasures as a

possible horizon for a different politics. The conclusions of our study force us

to be more cautious. Like the concepts of sex and sexuality, the concept of the

body too is always already caught in a deployment of power. The body is

always already a biopolitical body and bare life, and nothing in it or the

o e

oe

o e

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

456 P. Gratton

economy of its pleasure seems to allow us to find solid ground on which to

oppose the demands of sovereign power Today, a law that seeks to trans-

form itself wholly into life is more and more [again more and more]

confronted with a life that has been deadened and mortified into juridical rule

We are not only, in Foucaults words, animals whose life as living beings is

at issue in their politics, but also inversely citizens whose very politics is at

issue in their natural body It cannot be overcome in a passage to a new body

in which a different economy would not once and for all resolve the inter-

lacement of zo[ emacr ] and bios that seems to define the political destiny of the West.

(Agamben 1998: 188189, last emphasis added)

But Foucault never denied the bio-politicization of the body, a point repeated so

often in The History of Sexuality that no page citation is necessary. And Foucault

never lost sight of the role of sovereignty and law in the modern age of politics and

power, though, as we noted above, he saw sovereignty considerably diminished

and conflated the two. Just after calling for regicide in political theory, Foucault

notes:

I dont want to say that the state isnt important; what I want to say is that

relations of power, and hence analyses made of them, necessarily extend

beyond the limits of the state. In two senses: first of all because the State, for

all the omnipotence of its apparatuses, is far from being able to occupy the

whole field of actual power relations, and further because the state can only

operate on the basis of other already existing power relations. (Foucault 1980:

122, emphasis added)

In short, Foucault does not, as Agamben suggests, offer a dualism of puissance (an

incommunicable rupture between the power of the state and the powers from

below) thus Foucaults metaphor of the state as a crystallization of power. This is

all not to put forward an apologia for Foucault. By re-centralizing power in the

sovereign exception, Agamben offers a compelling thesis for the operation of a

certain vertical power, perhaps as the thinker on all the consequences of the sover-

eignty. For example, Agamben is on to something in The State of Exception in

applying his previous work to the Patriot Act and Bushs extra-constitutional

maneuvers post-11 September 2001 (though, as Agamben would likely point out,

the United States has not just in recent years become the rogue state that it is).

Certainly, Bush and his vice-president are Schmittian in their belief in the sovereign

exception, arguing that the executive, in protecting the laws of the United States,

ought not to have any limits placed upon it in exercising these laws. Thus, when the

president famously remarked in November 2005, after the publication of numerous

administration memos and Red Cross and other human-rights organizations reports

pointing to the contrary, that we do not torture and that the US government was

following the law, the tautology was clear, even in the American media. Our

country is at war, and our government has the obligation to protect the American

e

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty 457

people, Bush said, unknowingly repeating Foucaults 30-year old refrain on bio-

power, adding, anything we do to that effort, to that end, in this effort, any activity

we conduct, is within the law. As one web magazine put it, anything we do is

within the law because anything we do is within the law, given the administra-

tions claims that any actions it takes in the global war on terror is lawfully within

the presidents constitutional authority.

7

There is no need to revisit the ample

literature on this here.

8

But it is this focus on this state apparatus that has led some to look continually for

memos of evidence linking the presidents administration to abuses in Iraq,

Afghanistan, Cuba and in the reopened prison camps of Eastern Europe. For these

critics, this would be proof of our worst fears of bio-politics, that the state was itself

terrorist, reducing all its enemies to bare life, whether citizen or not. No doubt. But

what is more terrifying, what is more insidious about power relations is that the link

between the White House and the American guards committing atrocities may have

been a mere coincidence in goals, horizontal movements of power without a direct-

ing agent, that is, indeed, as a biopower, as Foucault put it, in excess of sovereign

right and human sovereignty. What is more insidious is that, across the world,

no top-down orders were needed in the operation of a certain bio-power, with power

and domination and, yes, a disciplining of other cultures operating horizontally

across a society expanding its reach. All this occurred without the needs for orders

of a sovereign as a society marginalizes and terrorizes the Other in the name of the

security of a particular population, while its troops experience the perverse

pleasure of power itself.

Notes

1. Foucaults use of the repressive hypothesis in the text is less as a critique of a broad swath of

psychoanalysis than as a straw man against which to discuss power. This straw man would be one

that cannot tell the categorical difference between repression and oppression, the latter being always

vertical in its essence. The former, I would argue, operates, in more polyvalent ways than Foucault

addresses in this short volume, as he admits (Foucault 1990: 8183). Such a notion of repression is

itself at work in Foucault when he addresses the question of sovereignty in the modern age: it is used

to conceal the polymorphism of power. Is this not really repression concealment and ruses brought

on by a certain desire within power relations in another guise? Isnt this what Foucault broaches

when he discusses the possiblity that underlying the scientia sexualis and perhaps with it, an entire

episteme of power is an ars erotica, a movement of pleasure that may underly this particular nexus

of power-knowledge? Is there not here, in Foucault, a very rich notion of repression, if he could

bring himself to use the word? It is notable that Foucault at once admits that few could or would

believe in a conception of power that is said to underlies the repressive hypothesis, though it does

have its adherents (notably, Reich, the target of the book finally announced in the last chapter), and

that mention of more complicated versions of desire in psychoanalysis is perfunctory.

2. See, for example, Deleuzes Foucault. Deleuze reads Foucault as positing two phases of power, from

the phase of sovereignty to the phase of polymorphic power: What is Foucault trying to say in the

best pages of The History of Sexuality? When the diagram of power abandons the model of sover-

eignty in favor of a disciplinary model, when it becomes bio-power or bio-politics of populations,

controlling and administering life, it is indeed life that emerges as the new object of power. At that

point, law increasingly renounces the symbol of sovereign priviledge, the right to put someone to

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

458 P. Gratton

death (the death penalty), but allows itself to produce all the more hecatombs and genocides in the

name of race, precious space and the survival of a population that believes itself to be better than

its enemy, which it now treats not as the juridical enemy of the old sovereign but as a toxic or

infectious agent (Deleuze 1980: 92).

3. Foucault dates this mutation in power to the writings of the counter-sovereigntists in eighteenth-

century France, mosty notably the Cont de Boulainvillier. For Foucault, Boulainvilliers forms such a

contrapuntal relationship to the history of his period, one which generally told only the history of

kings. Boulainvilliers work, for Foucault, is instrumental for rethinking society as one always at war

within itself, as a more or less horizontal movement of forces that has one of its nodal points in the

sovereign, but not reducible to this vertical relationship, as the royalists and their historical accounts

of the time assume. In other words, Boulainvilliers, according to Foucault, provides a precursor to

just the kind of thinking of power that Foucault believes operates in the modern period (Foucault

2004: 162174).

4. We can note again Foucaults conflation of sovereignty with the law: Law cannot help but be armed

The law always refers to the sword (Foucault 1978: 144). See also Power/Knowledge: To pose

the problem in terms of the state means to continue posing it in terms of sovereign and sovereignty,

that is to say, in terms of law (Foucault 1980: 122).

5. With the emergence of bio-power, Foucault argues, racism is inscribe[d] in the mechanisms of the

state. It is at this moment that racism is inscribed as the basic mechanism of power It is a way of

separating out groups that exist within a population. It is, in short, a way of establishing a biological-

type caesura within a population that appears to be a biological domain (Foucault 2004: 254255).

Racism, Foucault argues, serves two functions: (1) to make a subdivision of the races, of the species,

and (2) to make relations within a society not-war like, but rather, that of a biological-type relation-

ship. The reason this latter mechanism can come into play, he argues, is that enemies who have to

be done away with are not adversaries in the political sense of the term; they are threats, either exter-

nal or internal, to the population and for the population (2004: 255). In the biopower system, in

other words, killing or the imperative to killing is acceptable only if it results not in a victory over

political adversaries, but in the elimination of the biological threat to and the improvement of the

species or race (2004: 256). For a fuller discussion of Foucaults treatment of racism in Society

Must Be Defended, see Kelly 2004.

6. One should note the claustrophobia of sourcing in both Agamben and Foucault. Not only are their

works too distanced from the realities of colonialism and neo-colonialism that take place during the

phases of power they discuss, but their descriptions of the West make it seem as if Western Europe

were an enclave impervious to influence from the outside. Agambens work is particularly symptom-

atic of a certain Euro-centrism even among those who should know better. Agambens treatment of

the Rwandan genocide, to cite one example, is at best ill-informed; at worst, it repeats a typical

philosophical approach (found in Rousseaus essays on the global south, Kants Anthropology, and

Hegels lectures on history) of treating the others of Europe, in particular those on the African conti-

nent, as mere grist for the work of theory.

7. See War Room, Salon.com, 6 November 2005, and Michael Isikoff, 2001 Memo Reveals Push for

Broader Presidential Powers in Newsweek, 18 December 2004.

8. For example, Alfred W. McCoy (2006) provides an indispensable history of recent US policy on

torture and state terror.

References

Agamben, G. (1998) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stan-

ford, CA: Stanford University Press).

Agamben, G. (2005) State of Exception, trans. Kevin Attell (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press).

Benjamin, W. (1969) Theses on the philosophy of history, in: Arendt, H. (Ed.), Illuminations, pp. 253

263 (New York: Schocken).

Deleuze, G. (1988) Foucault, trans. San Hand (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press).

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Agamben via Foucault on Sovereignty 459

Foucault, M. (1978) History of Sexuality, Volume 1, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Random House).

Foucault, M. (1980) Power/Knowledge, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Harvester Press).

Foucault, M. (1994) Power, Vol. 3 of Essential Works of Foucault, ed. James Faubion (New York: New

Press, 1994).

Foucault, M. (2004) Society Must Be Defended, trans. David Macey (New York: Picador).

Kelly, M. (2004) Racism, nationalism, and biopolitics: Foucaults Society Must Be Defended,

Contretemps, 4(3), pp. 5870.

McCoy, A. (2006) A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror

(New York: Metropolitan Books).

Nancy, J.-L. (2000) Being Singular Plural (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press).

Schmitt, C. (1996) The Concept of the Political, trans. G. Schwab (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press).

Schmitt, C. (2006) Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. T. Strong

(Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press).

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

C

h

u

n

g

A

n

g

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

]

a

t

1

9

:

5

8

2

7

J

u

l

y

2

0

1

4

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Assemblage and GeographyDokumen4 halamanAssemblage and Geographyiam_ipBelum ada peringkat

- The Undecidable and The Fugitive Mille P PDFDokumen13 halamanThe Undecidable and The Fugitive Mille P PDFRafaelLosadaBelum ada peringkat

- Labor As Action. The Human Condition in The AnthropoceneDokumen21 halamanLabor As Action. The Human Condition in The AnthropoceneJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- A Conceptual History of BiopoliticsDokumen22 halamanA Conceptual History of BiopoliticsJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- The Masked AssassinationDokumen12 halamanThe Masked AssassinationJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Angel Government: The Theological Role of Angels in Worldly AffairsDokumen8 halamanAngel Government: The Theological Role of Angels in Worldly AffairsÖmer Faruk GökBelum ada peringkat

- Linguistic Aspects of TranslationDokumen9 halamanLinguistic Aspects of TranslationJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Maoism, Marxism of Our Time PDFDokumen12 halamanMaoism, Marxism of Our Time PDFJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Chow Yun-Fat and Territories of Hong Kong StardomDokumen4 halamanChow Yun-Fat and Territories of Hong Kong StardomJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- A Conceptual History of BiopoliticsDokumen18 halamanA Conceptual History of BiopoliticsJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Resistance - Abolition Now! Ten Years of Strategy and Struggle Against The Prison Industrial ComplexDokumen175 halamanCritical Resistance - Abolition Now! Ten Years of Strategy and Struggle Against The Prison Industrial ComplexCal Davis100% (1)

- Racial Profiling and The Societies of ControlDokumen13 halamanRacial Profiling and The Societies of ControlJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Limits of NeoliberalismDokumen185 halamanLimits of NeoliberalismBach Achacoso100% (4)

- Visible Signs of City Out of Control. Community Policing in New York CityDokumen26 halamanVisible Signs of City Out of Control. Community Policing in New York CityJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Constitution and IndividuationDokumen11 halamanConstitution and IndividuationJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Biopolitics of Security in The 21st CenturyDokumen55 halamanBiopolitics of Security in The 21st CenturyJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Genosko - The Bureaucratic Beyond - Roger Caillois and The Negation of The Sacred in Hollywood CDokumen17 halamanGenosko - The Bureaucratic Beyond - Roger Caillois and The Negation of The Sacred in Hollywood CJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Quest-Ce Que La BiopolitiqueDokumen7 halamanQuest-Ce Que La BiopolitiqueJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- From Domestic To Global Solidarity. The Dialectic of The Particular and Universal in The Building of Social SolidarityDokumen18 halamanFrom Domestic To Global Solidarity. The Dialectic of The Particular and Universal in The Building of Social SolidarityJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Racial Profiling and The Societies of ControlDokumen13 halamanRacial Profiling and The Societies of ControlJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- JWSR - 05-2Dokumen166 halamanJWSR - 05-2Jaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Chomsky - Language and NatureDokumen62 halamanChomsky - Language and NatureJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- A Conceptual History of BiopoliticsDokumen18 halamanA Conceptual History of BiopoliticsJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Biopolitics of Security in The 21st CenturyDokumen55 halamanBiopolitics of Security in The 21st CenturyJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Peters CV 2013 04Dokumen7 halamanPeters CV 2013 04Jaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- I Want To Think POST-UDokumen5 halamanI Want To Think POST-UJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Immaterial LabourDokumen9 halamanImmaterial LabourDan ScatmanBelum ada peringkat

- Examining the Tensions Between Human Dignity and CapitalismDokumen171 halamanExamining the Tensions Between Human Dignity and CapitalismJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- To Be Hospitable To Madness. Derrida and Foucault Chez FreudDokumen19 halamanTo Be Hospitable To Madness. Derrida and Foucault Chez FreudJaewon LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Final ProjectDokumen5 halamanFinal ProjectAkshayBelum ada peringkat

- Paper 1 Potential QuestionsDokumen8 halamanPaper 1 Potential QuestionsDovid GoldsteinBelum ada peringkat

- Order 3520227869817Dokumen3 halamanOrder 3520227869817Malik Imran Khaliq AwanBelum ada peringkat

- Business Law - Chapter 1 PDFDokumen3 halamanBusiness Law - Chapter 1 PDFJOBY LACC88100% (1)

- Brown v. YambaoDokumen2 halamanBrown v. YambaoBenjie CajandigBelum ada peringkat

- Karaomerlioglu, Asım - Alexander Helphand-Parvus and His Impact On Turkish Intellectual LifeDokumen21 halamanKaraomerlioglu, Asım - Alexander Helphand-Parvus and His Impact On Turkish Intellectual LifebosLooKBelum ada peringkat

- QUAL7427613SYN Cost of Quality PlaybookDokumen58 halamanQUAL7427613SYN Cost of Quality Playbookranga.ramanBelum ada peringkat

- Group Reflection Paper On EthicsDokumen4 halamanGroup Reflection Paper On EthicsVan TisbeBelum ada peringkat

- CGTMSE PresentationDokumen20 halamanCGTMSE Presentationsandippatil03Belum ada peringkat

- Legal Terminology Translation 1 30Dokumen195 halamanLegal Terminology Translation 1 30khmerweb100% (1)

- Freezing of subcooled water and entropy changeDokumen3 halamanFreezing of subcooled water and entropy changeAchmad WidiyatmokoBelum ada peringkat

- 01 Fundamental of Electrical Engineering 20170621Dokumen26 halaman01 Fundamental of Electrical Engineering 20170621Sabita Talukdar100% (1)

- Audition Guide for "Legally BlondeDokumen6 halamanAudition Guide for "Legally BlondeSean Britton-MilliganBelum ada peringkat

- The Krugersdorp KillersDokumen105 halamanThe Krugersdorp KillersStormwalker9100% (3)

- Working Capital Management Cash ManagementDokumen9 halamanWorking Capital Management Cash ManagementRezhel Vyrneth TurgoBelum ada peringkat

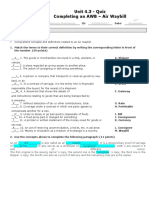

- 1DONE2. CX Quiz 4.3 - Air WaybillDokumen1 halaman1DONE2. CX Quiz 4.3 - Air WaybillProving ThingsBelum ada peringkat

- Руководство Учебного Центра SuperJet (Moscow)Dokumen174 halamanРуководство Учебного Центра SuperJet (Moscow)olegprikhodko2809100% (2)

- Lincoln's Yarns and Stories: A Complete Collection of The Funny and Witty Anecdotes That Made Lincoln Famous As America's Greatest Story Teller by McClure, Alexander K. (Alexander Kelly), 1828-1909Dokumen317 halamanLincoln's Yarns and Stories: A Complete Collection of The Funny and Witty Anecdotes That Made Lincoln Famous As America's Greatest Story Teller by McClure, Alexander K. (Alexander Kelly), 1828-1909Gutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- How How-To-Install-Plugins-Vplug To Install Plugins Vplug ProgramDokumen4 halamanHow How-To-Install-Plugins-Vplug To Install Plugins Vplug ProgramMario BoariuBelum ada peringkat

- Altair AcuFieldView 2021.1 User GuideDokumen133 halamanAltair AcuFieldView 2021.1 User GuideakashthilakBelum ada peringkat

- Stark County Area Transportation Study 2022 Crash ReportDokumen148 halamanStark County Area Transportation Study 2022 Crash ReportRick ArmonBelum ada peringkat

- MMDA Bel Air Case DigestDokumen2 halamanMMDA Bel Air Case DigestJohn Soliven100% (3)

- Cracks Within The Catholic Church and The Cavite MutinyDokumen31 halamanCracks Within The Catholic Church and The Cavite MutinyHaidei Maliwanag PanopioBelum ada peringkat

- The Rich Cheat and Become Richer Discover How We Let The Rich Thrive and How We Can Stop Them by Fixing CapitalismDokumen251 halamanThe Rich Cheat and Become Richer Discover How We Let The Rich Thrive and How We Can Stop Them by Fixing Capitalismcharles yerkesBelum ada peringkat

- International Criminal Law PDFDokumen14 halamanInternational Criminal Law PDFBeing IndianBelum ada peringkat

- SL-M3870FD XAX Exploded ViewDokumen28 halamanSL-M3870FD XAX Exploded Viewherba3Belum ada peringkat

- Mac16Cm, Mac16Cn Triacs: Silicon Bidirectional ThyristorsDokumen6 halamanMac16Cm, Mac16Cn Triacs: Silicon Bidirectional Thyristorsmauricio zamoraBelum ada peringkat

- Organic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDDokumen3 halamanOrganic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDKhoo Chin KangBelum ada peringkat

- Provincial Investigation and Detective Management Unit: Pltcol Emmanuel L BolinaDokumen17 halamanProvincial Investigation and Detective Management Unit: Pltcol Emmanuel L BolinaCh R LnBelum ada peringkat

- Art. 779. Testamentary Succession Is That Which Results From The Designation of An Heir, Made in A Will Executed in The Form Prescribed by Law. (N)Dokumen39 halamanArt. 779. Testamentary Succession Is That Which Results From The Designation of An Heir, Made in A Will Executed in The Form Prescribed by Law. (N)Jan NiñoBelum ada peringkat