1 s2.0 S0272638607013686 Main

Diunggah oleh

RatnaVelugu0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

14 tayangan8 halamanPeriodontal Disease and Other Nontraditional Risk Factors for CKD

Monica A. Fisher, PhD, DDS, MPH,1 George W. Taylor, DMD, DrPH,2 Brent J. Shelton, PhD,3

Kenneth A. Jamerson, MD,2 Mahboob Rahman, MD, MS,1 Akinlolu O. Ojo, MD, PhD,2 and

Ashwini R. Sehgal, MD1

Judul Asli

1-s2.0-S0272638607013686-main

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniPeriodontal Disease and Other Nontraditional Risk Factors for CKD

Monica A. Fisher, PhD, DDS, MPH,1 George W. Taylor, DMD, DrPH,2 Brent J. Shelton, PhD,3

Kenneth A. Jamerson, MD,2 Mahboob Rahman, MD, MS,1 Akinlolu O. Ojo, MD, PhD,2 and

Ashwini R. Sehgal, MD1

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

14 tayangan8 halaman1 s2.0 S0272638607013686 Main

Diunggah oleh

RatnaVeluguPeriodontal Disease and Other Nontraditional Risk Factors for CKD

Monica A. Fisher, PhD, DDS, MPH,1 George W. Taylor, DMD, DrPH,2 Brent J. Shelton, PhD,3

Kenneth A. Jamerson, MD,2 Mahboob Rahman, MD, MS,1 Akinlolu O. Ojo, MD, PhD,2 and

Ashwini R. Sehgal, MD1

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 8

Periodontal Disease and Other Nontraditional Risk Factors for CKD

Monica A. Fisher, PhD, DDS, MPH,

1

George W. Taylor, DMD, DrPH,

2

Brent J. Shelton, PhD,

3

Kenneth A. Jamerson, MD,

2

Mahboob Rahman, MD, MS,

1

Akinlolu O. Ojo, MD, PhD,

2

and

Ashwini R. Sehgal, MD

1

Background: Chronic kidney disease, undiagnosed in a signicant number of adults, is a public

health problem. Given the systemic inammatory response to periodontal disease, we hypothesized

that periodontal disease could be associated with chronic kidney disease.

Study Design: Cross-sectional.

Setting & Participants: We identied 12,947 adults 18 years or older with information for kidney

function and at least one risk factor in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Predictor: The main predictor was periodontal status. Other nontraditional and traditional risk factors

included socioeconomic status, health status, health behavior, biomarker levels, anthropometric assess-

ment, and health care utilization.

Outcomes & Measurements: Chronic kidney disease was dened using the Kidney Disease

Outcomes Quality Initiative stages 3 and 4 with a moderate to severe decrease in kidney function

(glomerular ltration rate, 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m

2

). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression

models assessed the associations between chronic kidney disease and periodontal disease and other

nontraditional risk factors.

Results: Chronic kidney disease prevalence was 3.6%; periodontal disease prevalence was 6.0%;

and edentulism prevalence was 10.5%. Adults with periodontal disease and edentulous adults were

twice as likely to have chronic kidney disease (adjusted odds ratio, 1.60; 95% condence interval, 1.16

to 2.21; adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% condence interval, 1.34 to 2.56, respectively) after simulta-

neously adjusting for other traditional and nontraditional risk factors.

Limitations: Temporal association is unknown.

Conclusions: Periodontal disease and its severe consequence, edentulism, were independently

associated with chronic kidney disease after adjusting for other traditional and nontraditional risk factors.

This model could contribute to identifying individuals at risk of chronic kidney disease and reduce its

burden.

Am J Kidney Dis 51:45-52. 2007 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc.

INDEX WORDS: Chronic kidney disease; diabetes mellitus; edentulism; glomerular ltration rate;

hypertension; macroalbuminuria; periodontal disease.

C

hronic kidney disease (CKD) is a public

health problem that is undiagnosed in a

signicant number of those affected in the United

States.

1-3

Serious sequelae related to CKD in-

clude end-stage kidney failure, cardiovascular

disease, and premature death, with death and

cardiovascular events more common than pro-

gression to kidney failure.

4-6

The risk of these

serious sequelae increases as glomerular ltra-

tion rate (GFR) decreases to less than 60 mL/min/

1.73 m

2

(1.0 mL/s/1.73 m

2

).

4-6

This level of

moderate to severe decrease in kidney function

corresponds to the National Kidney Foundation-

Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative

stages 3 and 4 CKD, dened as a GFR of 15 to 59

mL/min/1.73 m

2

(0.25 to 0.98 mL/s/1.73 m

2

).

1

Identication of undiagnosed high-risk indi-

viduals is needed to provide the opportunity for

early detection and intervention to prevent or

delay the onset of end-stage renal disease and

cardiovascular events. Other than one recently

reported prediction model,

7

high-risk subgroups

for CKD typically were identied through a

single traditional risk factor: age older than 60

years,

1,7,8

hypertension,

2,8,9-15

diabetes,

2,7-16

poor

glycemic control,

1,11,12

obesity,

2,12-16

macroalbu-

minuria,

1,3,8,17

smoking,

1,9,12,14-16

C-reactive

protein level,

14,18,19

elevated total choles-

terol level,

1,12,14

low high-density lipoprotein

1

From Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH;

2

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; and

3

University of

Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

Received June 2, 2007. Accepted in revised form Septem-

ber 18, 2007.

This work was done at Case Western Reserve University.

Address correspondence to Monica A. Fisher, PhD, DDS,

MPH, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve Univer-

sity, 10900 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106-4905.E-mail:

monica.sher@case.edu

2007 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc.

0272-6386/07/5101-0007$34.00/0

doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.018

American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Vol 51, No 1 (January), 2008: pp 45-52 45

level,

1,10,12,15

elevated low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol level,

15

race/ethnicity,

1,11,13,14,16

gen-

der,

1,7,9,12,14-16

and income/poverty.

1,13

Recently,

nontraditional risk factors were reported that

may contribute to CKD, such as periodontal

disease,

20-22

education,

13,16

and health care utili-

zation.

13,23

The rationale for considering periodontal dis-

ease as a nontraditional risk factor for CKD

centers around the inammatory response to peri-

odontal disease adding to the chronic systemic

inammatory burden associated with CKD. The

role of chronic inammatory burden in patients

with CKD was reported through the association

between C-reactive protein level and CKD.

19,24

Thus, we speculate that periodontal disease may

contribute to CKD because periodontal disease,

more specically chronic periodontitis, is a

chronic infectious disease caused by gram-

negative bacteria with a persistent host inamma-

tory response. The loss of attachment of the

periodontal ligament and bony support of the

teeth can lead to tooth loss. In adults, periodontal

disease is a major cause of edentulism.

25

The

response to periodontal pathogens leads to a

local tissue-destructive immunoinammatory re-

sponse thought to create a chronic systemic in-

ammatory burden secondary to the systemic

dissemination of periodontal pathogenic bacte-

ria, their products (eg, lipopolysaccharides), and

locally produced inammatory mediators (eg,

interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor , interleu-

kin 6, prostaglandin E

2

, and thromboxane

B2).

26,27

Furthermore, an acute-phase inamma-

tory response, measured by using elevated C-

reactive protein level, is associated with periodon-

tal disease and edentulism after controlling for

other risk factors for elevated C-reactive protein

level.

28

A similar focus on the systemic inammatory

burden of chronic periodontal disease was hypoth-

esized to contribute to endothelial injury and

atherogenesis.

29

An increasing body of epidemio-

logical evidence supports a signicant associa-

tion between periodontal disease and cardiovas-

cular diseases.

30,31

Additionally, several clinical

studies involving the treatment of patients with

chronic periodontitis reported an improvement

in secondary end points considered important in

cardiovascular disease risk,

27

including a re-

cently reported randomized clinical trial show-

ing a signicant improvement in endothelial func-

tion after periodontal treatment.

29

Chronic inammation is one of the common

risk factors for both atherosclerotic cardiovascu-

lar disease and CKD. Evidence also exists to

support chronic inammation contributing to the

pathogenesis of hypertension and diabetes melli-

tus, both major risk factors for cardiovascular

disease and CKD.

32

Based on the current evi-

dence that periodontal disease is a source of

systemic inammatory burden, it is biologically

plausible to hypothesize that periodontal disease

is a risk factor for CKD.

The use of single risk factors to identify sub-

groups at high risk of CKD is a major limitation

that can be addressed by simultaneously consid-

ering a set of risk factors. Recently, Bang et al

7

proposed a multivariable prediction model for

CKD and also reported that no other multivari-

able method existed to predict CKD. Our study

contributes to helping health care providers iden-

tify patients at high risk of CKD by simulta-

neously considering recognized traditional risk

factors and suspected nontraditional risk factors,

including periodontal disease and one of its im-

portant sequelae, edentulism, in a representative

sample of the US population.

The objective of our study is to investigate the

role of periodontal disease and other nontradi-

tional risk factors in patients with CKD by: (1)

describing and quantifying the relationship be-

tween CKD and periodontal disease, along with

the relationship between CKD and other nontra-

ditional and traditional risk factors, in the Third

National Health and Nutrition Examination Sur-

vey (NHANES III)

33

; and (2) developing a mul-

tivariable model for the association between CKD

and periodontal disease and other nontraditional

risk factors, adjusting for traditional risk factors

to identify risk factors independently associated

with the presence of CKD.

MATERIALS

Study Population

This cross-sectional study was deemed exempt by the

institutional review board, and all investigators complied

with the Data Use Restrictions for the NHANES III public-

use data set collected by the National Center for Health

Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

NHANES III, 1988-1994, is a complex, multistage, strati-

ed, clustered sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized US

population representative of the US population. NHANES

Fisher et al 46

includes questionnaire, laboratory-assay, and clinical-exami-

nation measures of health outcomes and explanatory vari-

ables. Data used in this study are: (1) responses to questions

regarding age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, education,

smoking, diabetes, and hypertension; (2) laboratory assays

of serum cotinine, glycated hemoglobin, plasma glucose,

serum C-reactive protein, serum creatinine, serum total

cholesterol, serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, se-

rum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, urinary albumin,

and urinary creatinine; and (3) clinical examination data for

systolic and diastolic blood pressure, height, weight, and

periodontal status. We identied 12,947 adults 18 years or

older representing 140.2 million Americans with informa-

tion for kidney function and at least one risk factor, of which

11,955 had information for kidney function and all risk

factors tested in multivariable modeling.

Description of Main Outcome

The main outcome was stages 3 and 4 CKD with moder-

ate to severe decrease in kidney function, dened as GFR of

15 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m

2

(0.25 to 0.98 mL/s/1.73 m

2

).

1

This

denition was reported to be a more precise estimate of

decreased kidney function.

3

Henceforth, we refer to this

denition of stages 3 and 4 CKD simply as CKD. GFR was

estimated by using the 4-variable Modication of Diet in

Renal Disease Study equation: GFR 186.3 (serum

creatinine [mg/dL])

1.154

age

0.203

(0.742 if female)

(1.21 if black). Serum creatinine value was calibrated by

subtracting the value of 0.23 to align the NHANES measures

with creatinine assays in the aforementioned equation.

34

Description of Risk Factors

The principal exposure or predictor for this analysis is

periodontal status based on a clinical examination, and

categorized as no periodontal disease, periodontal disease,

or edentulous. Periodontal disease is dened as one or more

sites with both 4 mm or greater loss of attachment and

bleeding on the same tooth (bleeding as an indicator of

active inammation).

35

Edentulous is dened as having lost

all natural teeth. Other traditional and suspected nontradi-

tional risk factors for CKD included in the analyses are

socioeconomic status (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income,

and education), health status (diabetes mellitus and systemic

hypertension), health behavior and biomarker levels (smok-

ing, macroalbuminuria, C-reactive protein, total cholesterol,

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low-density lipopro-

tein cholesterol), anthropometric assessment (body mass

index), and health care utilization (self-report of an annual

physician visit or hospitalization in the past year).

Lower income is dened as less than $20,000 annual

household income. Diabetes mellitus status is categorized as

no diabetes, diabetes with good control (7% glycated

hemoglobin), and diabetes with poorer control (7% gly-

cated hemoglobin). Diabetes mellitus is dened as fasting

plasma glucose level of 126 mg/dLor greater (7.0 mmol/L)

or 200 mg/dL or greater (11.1 mmol/L) after an oral

glucose tolerance test, or self-reported physician-diagnosed

diabetes. Systemic hypertension is dened as systolic blood

pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure

greater than 90 mm Hg, or being told on two or more

different visits that one had hypertension. Macroalbuminuria

is dened as urinary albumin-creatinine excretion ratio of

300 mg/g or greater. Self-reported smoking status is current,

former, or never, excluding those who reported former or

never smoking but were current smokers based on the gold

standard of serum cotinine levels of 15 ng/mL or greater

(85 nmol/L).

36

Obesity is dened as a body mass index

greater than 27 kg/m

2

. High C-reactive protein level is

dened as greater than 3.0 mg/dL.

Statistical Analyses

Tests of the hypothesis that CKD is associated with

traditional and nontraditional risk factors used univariable

and multivariable logistic regression modeling. Covariates

were selected by using a stepwise regression approach with

P value less than 0.05 as the selection criterion to enter and

remain in the model. This approach simultaneously took into

account the statistically signicant risk factors determined

by means of univariable analyses, with statistical signi-

cance reported as a 95% condence interval (CI). The

independent association between CKD and risk factors,

namely, socioeconomic status, health status, health behavior

and biomarker levels, and health care utilization, was quanti-

ed by calculating the adjusted odds ratio (OR

Adj

). Model t

was assessed by means of the Satterthwaite-adjusted F

statistic test, accounting for the complex study design. Thus,

we compared the nal full model with periodontal disease to

the reduced model with all the same covariates excluding

periodontal status. Analyses were conducted using SAS-

Callable SUDAAN, version 9.0.1 (Research Triangle Insti-

tute, Research Triangle Park, NC)

37

and SAS Systems for

Windows, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) to

account for complex survey design and sample weights and

to produce national estimates.

RESULTS

Overall Descriptive Summary

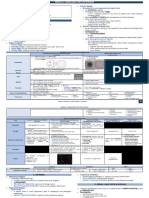

Table 1 presents important characteristics of

the study population and their unadjusted associa-

tion with CKD. Overall, 3.6% of the study popu-

lation had CKD, 6.0% had periodontal disease,

10.5% were edentulous, 23.5% were hyperten-

sive, and 36.4% were obese. The univariable

models reported in Table 1 are similar to the

typical approach that reports a single risk factor

without adjusting for potential confounders. For

example, an adult with the nontraditional risk

factor edentulism was over 10 times more likely

to have CKD (odds ratio [OR

Crude

], 10.38; 95%

CI, 7.87 to 13.70) than an adult without periodon-

tal disease. Likewise, an adult with periodontal

disease was 4 times more likely to have CKD

(OR

Crude

, 3.93; 95% CI, 2.95 to 5.24) than an

adult without periodontal disease.

Periodontal Disease and CKD 47

Table 1. Descriptive Summary and Association Between CKD and Periodontal Disease and Other Risk Factors

No CKD CKD OR

Crude

Risk Factors (n 12,330; 96.4%) (n 617; 3.6%) (95% CI)

Socioeconomic status

Age (y)

18-59 (n 9,575; 81.4%) 83.9% 16.3% 1.00

60 (n 3,372; 18.6%) 16.1% 83.7% 26.78 (17.74-40.43)*

Race/ethnicity

Non-Hispanic white (n 5,051; 82.2%) 81.9% 91.3% 5.57 (3.88-8.01)*

Non-Hispanic black (n 3,472; 11.5%) 11.7% 7.4% 3.18 (2.11-4.79)*

Mexican-American (n 3,890; 6.3%) 6.4% 1.3% 1.00

Gender

Female (n 6,922; 52.5%) 52.1% 61.8% 1.49 (1.11-1.99)*

Male (n 6,025; 47.5%) 47.9% 38.2% 1.00

Lower income

Yes (n 6,004; 32.0%) 31.1% 56.7% 2.90 (2.31-3.65)*

No (n 6,725; 68.0%) 68.9% 43.3% 1.00

High school graduate

Yes (n 7,826; 76.6%) 77.5% 53.8% 1.00

No (n 5,040; 23.4%) 22.5% 46.2% 2.95 (2.31-3.78)*

Health status and health behavior

Periodontal status

Edentulous (n 1,610; 10.5%) 9.2% 41.8% 10.38 (7.87-13.70)*

Periodontal disease (n 1,271; 6.0%) 5.8% 11.2% 3.93 (2.95-5.24)*

No periodontal disease (n 10,066; 83.5%) 85.0% 47.0% 1.00

Diabetes

Poor control (n 642; 3.1%) 2.8% 12.1% 5.22 (3.19-8.53)*

Good control (n 512; 3.0%) 2.7% 9.7% 4.32 (2.98-6.27)*

No diabetes (n 11,784; 93.9%) 94.5% 78.2% 1.00

Hypertension

Yes (n 3,659; 23.5%) 21.7% 70.8% 8.73 (6.93-10.99)*

No (n 9,274; 76.5%) 78.3% 29.2% 1.00

Macroalbuminuria

Yes (n 231; 1.0%) 0.7% 8.4% 12.71 (7.92-20.42)*

No (n 12,716; 99.0%) 99.3% 91.6% 1.00

Obesity

Yes (n 5,463; 36.4%) 36.0% 47.4% 1.61 (1.27-2.03)*

No (n 7,460; 63.6%) 64.0% 52.6% 1.00

High C-reactive protein

Yes (n 171; 1.0%) 0.9% 2.8% 3.14 (1.56-6.33)*

No (n 12,767; 99.0%) 99.1% 97.2% 1.00

High cholesterol

Yes (n 2,403; 18.0%) 17.2% 38.9% 3.06 (2.45-3.83)*

No (n 10,505; 82.0%) 82.8% 61.1% 1.00

Low high-density lipoprotein

Yes (n 1,560; 12.9%) 12.6% 20.5% 1.78 (1.34-2.36)*

No (n 11,256; 87.1%) 87.4% 79.5% 1.00

High low-density lipoprotein

Yes (n 948; 16.3%) 15.8% 32.2% 2.53 (1.72-3.70)*

No (n 4,600; 83.7%) 84.2% 67.8% 1.00

Smoking status

Never (n 6,739; 48.2%) 48.3% 44.9% 1.96 (1.40-2.74)*

Former (n 2,753; 22.4%) 21.7% 40.8% 3.95 (2.83-5.53)*

Current (n 3,455; 29.4%) 30.0% 14.3% 1.00

Hospitalized in past year

Yes (n 1,661; 11.3%) 10.8% 23.0% 2.45 (1.89-3.18)*

No (n 11,250; 88.7%) 89.2% 77.0% 1.00

Annual physician visit

Yes (n 10,190; 80.8%) 80.4% 92.2% 2.90 (1.87-4.50)*

No (n 2,656; 19.2%) 19.6% 7.8% 1.00

Note: Unweighted number with weighted percent. Excludes those who reported never or former smoking with serum

cotinine level indicating current smoker. Inclusion criteria were periodontal examination or edentulous.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR

Crude

, unadjusted odds ratio for the association between CKD and the

suspected/recognized risk factors; CI, condence interval.

*P 0.05.

Fisher et al 48

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model

for the Association Between CKD and

Periodontal Disease and Other

Nontraditional Risk Factors

Table 2 presents the most parsimonious model

we estimated for the association between CKD

and periodontal disease and other nontraditional

risk factors, simultaneously adjusting for the

listed risk factors and reporting OR

Adj

and 95%

CI for each risk factor. Adults with periodontal

disease and edentulous adults were approxi-

mately twice as likely to have CKD (OR

Adj

,

1.60; 95% CI, 1.16 to 2.21; OR

Adj

, 1.85; 95% CI,

1.34 to 2.56, respectively) than adults without

periodontal disease after simultaneously adjust-

ing for age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, smok-

ing status, macroalbuminuria, hypertension, total

cholesterol level, high-density lipoprotein choles-

terol level, and hospitalizations, and physician

visits in the past year. It is also noted that older

adults were over 10 times more likely to have

CKD (OR

Adj

, 10.32; 95% CI, 6.97 to 15.27) than

younger adults after simultaneously adjusting for

the other statistically signicant risk factors or

risk indicators.

The t of the nal full model with periodontal

status listed in Table 2 is improved compared to

the reduced model with the same risk factors

excluding periodontal status, based on the Satter-

thwaite-adjusted F statistic P value of 0.0005.

This indicates that including periodontal status in

the model provides a statistically signicant con-

tribution to a model that excluded periodontal

status.

DISCUSSION

In our US population-based study, periodontal

disease and edentulism, as well as the nontradi-

tional risk factors that included having an annual

physician visit and being hospitalized in the past

year, were independently associated with CKD

after simultaneously adjusting for the following

traditional risk factors: age, race/ethnicity, gen-

der, smoking status, income, hypertension, mac-

roalbuminuria, total cholesterol level, and high-

density lipoprotein cholesterol level. Our

univariable unadjusted models support the previ-

ous studies that described high-risk subgroups by

using a single risk factor.

1-3,8-23

Additionally, our

study of a sample representative of the US popu-

lation provides a basis to extend the list of

potential nontraditional risk factors to include

periodontal disease status in a multivariable

model for the outcome CKD.

The ndings of this study suggest the impor-

tance of simultaneously taking into account other

risk factors, rather than the typical approach of

identifying high-risk subgroups for CKD based

on a single risk factor. By comparing the OR

Crude

with the OR

Adj

, the need to consider these other

covariates is evident. For example, when age

was the only risk factor considered, older adults

were 27 times more likely to have CKD. How-

ever, when the other risk factors were simulta-

neously taken into account, older adults were 10

times more likely to have CKD. Likewise, when

periodontal status was the only risk factor consid-

ered, adults with edentulism were over 10 times

more likely to have CKD, and adults with peri-

odontal disease were 4 times more likely to have

CKD. However, when the other risk factors were

Table 2. Multivariable Model for the Association

Between CKD and Periodontal Disease and Other

Risk Factors

Risk Factors Final Model OR

Adj

(95% CI)

Age 60 y 10.32 (6.97-15.27)*

Macroalbuminuria 5.13 (2.74-9.63)*

Race/ethnicity

Non-Hispanic white

Non-Hispanic black

3.53 (2.36-5.28)*

2.40 (1.57-3.68)*

Hypertension 2.12 (1.66-2.71)*

Smoking status

Former smoker

Never smoker

1.99 (1.41-2.79)*

1.55 (1.10-2.20)*

Periodontal status

Edentulous

Periodontal disease

1.85 (1.34-2.56)*

1.60 (1.16-2.21)*

Low high-density lipoprotein 1.80 (1.24-2.60)*

Hospitalized in past year 1.68 (1.24-2.27)*

Low income 1.65 (1.29-2.11)*

Annual physician visit 1.65 (1.10-2.50)*

High cholesterol level 1.47 (1.14-1.90)*

Female 1.45 (1.05-2.01)*

Note: The following risk factors were not included in the

nal model because they were not statistically signicant:

education, diabetes status, high C-reactive protein level,

and high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level. Ex-

cludes those who reported never or former smoking with

serum cotinine level indicating current smoker.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR

Adj

, odds

ratio for the association between CKD, simultaneously

taking into account all the listed potential or recognized risk

factors; CI, condence interval.

*P 0.05.

Periodontal Disease and CKD 49

simultaneously considered, adults with edentu-

lism were almost twice as likely, and adults with

periodontal disease were over 1 times more

likely to have CKD. In addition, when diabetes

status, obesity, C-reactive protein level, and edu-

cation were considered separately, they were

signicant. However, after simultaneously tak-

ing into account the other risk factors, including

periodontal disease status, they were no longer

signicant.

Although African Americans were reported to

be more likely to have CKD than whites,

4,11

this

was not found in our study or in a previous

NHANES III study.

3

This inconsistency may be

partly explained by racial disparity in survival,

such that the prevalence of CKD may be greater

in non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic blacks,

whereas the incidence is greater in non-Hispanic

blacks, but they do not survive as long. In addi-

tion, our ndings of greater racial disparities in

unadjusted than adjusted analyses indicate that

results are partly explained by confounding due

to health status, health behaviors, socioeconomic

characteristics, and health care utilization.

An important limitation of this study is its

cross-sectional design, which did not allow for

assessment of temporality. To establish causality,

it is imperative to show that periodontal disease,

as the exposure, precedes the development or

progression of CKD. This cannot be determined

in a cross-sectional study. Another limitation to

consider is that factors that lead to CKD could

also lead to periodontal disease. These are both

chronic conditions that progress in severity. Simi-

lar to the 5 progressive stages of CKD, periodon-

tal disease progresses with increasing loss of

connective tissue attachment and bony support,

often ultimately resulting in tooth loss. Based on

the review of traditional and nontraditional risk

factors for CKD reported herein, and a thorough

recent review of risk factors for periodontal

disease,

38

and more recent publications,

29,30

the

following potential confounders/risk factors are

in common for both diseases and were consid-

ered in our modeling: age, race/ethnicity, gender,

income, education, poorly controlled diabetes,

smoking, obesity, C-reactive protein level, cho-

lesterol level, high-density lipoprotein choles-

terol level, and low-density lipoprotein choles-

terol level. Support for periodontal status having

an independent association with CKD comes in

part from our analytical modeling approach that

involved the simultaneous assessment of poten-

tial confounders/risk factors common to both

periodontal disease and CKD.

Although we make no claims of causality,

several other features of this study warrant fur-

ther consideration of periodontal disease as a

potential risk factor for CKD. First, we found

that the strength of the unadjusted association for

the nontraditional risk factors edentulism and

periodontal disease is similar to the unadjusted

association between the traditional risk factor

poorly controlled diabetes. Second, the signi-

cant association we found is consistent with

previous studies nding a signicant association

between periodontal disease and renal dis-

ease.

20-22

Third, there is biological plausibility

for chronic periodontal disease as a source of

systemic inammatory burden

28

contributing to

the chronic inammation associated with CKD.

Fourth, our results are consistent with a dose-

response for periodontal status. When we as-

sessed a dose-response ranging fromno periodon-

tal disease to mild to moderate periodontal disease

to severe periodontal disease with 6 mm or

greater loss of attachment,

35

or 80th percentile of

the highest percentage of teeth with periodontal

disease, to edentulous, we found a dose-response

in which the odds of CKD increased as the

severity or extent of periodontal disease in-

creased, similar to that previously reported.

20

Our study has several other strengths. First,

we focused on the simultaneous assessment of

recognized and suspected risk factors for CKD,

nding that some previously recognized factors

were no longer signicant, whereas infrequently

studied nontraditional risk factors, namely peri-

odontal disease and edentulism, remained signi-

cant in the nal multivariable model. Second, the

nal model simultaneously considered 12 risk

factors for CKD rather than looking at only a

single factor at a time. Third, we addressed the

possibility that patients may deny smoking by

incorporating an objective smoking measure (ie,

serum cotinine).

39

Fourth, NHANES III sam-

pling methodology is designed to represent the

US population. Fifth, questionnaire, examina-

tion, and laboratory data were collected in an

unbiased manner such that participants were un-

aware of our study of risk factors for CKD. This

allowed us to investigate multiple recognized

Fisher et al 50

traditional and suspected nontraditional risk fac-

tors. Sixth, data were available for adults who

did not have an annual physician visit, unlike

other studies limited to patients who visited

health care providers.

The next step is to test our model in longitudi-

nal studies. Periodontal therapy may be consid-

ered along with the recommendation to counsel

high-risk individuals to reduce their risk by modi-

fying their behavior, such as smoking-cessation

counseling,

40

diet modication, and exercise,

along with antihypertensive drug therapy.

1,11,41

In summary, our ndings support the conclu-

sion that periodontal disease and edentulism are

potential nontraditional risk factors indepen-

dently associated with CKD in US adults. These

results support the importance of oral health

because adults with periodontally diseased teeth

and adults who lost all their teeth were more

likely to have CKD after controlling for tradi-

tional and nontraditional risk factors. As more

studies of CKD assess the role of periodontal

disease, data will accumulate to support or refute

the inclusion of periodontal therapy in preven-

tive targeted approaches to impede the increas-

ing numbers of individuals with CKD. Addi-

tional research is needed fromprospective studies

to help assess the causal inference and from

intervention studies to assess a decrease in inci-

dence, progression, and complications of CKD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support: This study was supported by grants DE016031-03

and DE016031-04 from the National Institutes of Health.

Financial Disclosure: None.

REFERENCES

1. National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI Clinical Prac-

tice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation,

classication, and stratication. Am J Kidney Dis 39:S1-

S266, 2002 (suppl 1)

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Preva-

lence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors

United States, 1999-2004. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly

Rep 56:161-165, 2007

3. Coresh J, Byrd-Hold D, Astor BC, et al: Chronic

kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among

U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:180-188,

2005

4. Go A, Chertow G, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu Cy:

Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascu-

lar events and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351:1296-1305,

2004

5. Keith DS, Nichols GA, Guillion CM, Brown JB, Smith

DH: Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a popula-

tion with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care

organization. Arch Intern Med 164:659-663, 2004

6. Rahman M, Pressel S, Davis BR, et al: Cardiovascular

outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients stratied by

baseline glomerular ltration rate. Ann Intern Med 144:172-

180, 2006

7. Bang H, Vupputuri S, Shoham DA, et al: SCreening

for Occult REnal Disease (SCORED): A simple prediction

model for chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 167:

374-381, 2007

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Green T, Levey AS: Assessing

kidney functionMeasured and estimated glomerular ltra-

tion rate. N Engl J Med 354:2473-2483, 2006

9. Haroun MK, Jaar BG, Hoffman SC, Comstock GW,

Klag MJ, Coresh J: Risk factors for chronic kidney disease:

A prospective study of 23,534 men and women in Washing-

ton County, Maryland. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:2934-2941,

2003

10. Sarnak MJ, Levy AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al: Kidney

disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular

disease: A statement from the American Heart Association

Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood

Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology

and Prevention. Hypertension 42:1050-1065, 2003

11. Jamerson KA: Preventing chronic kidney disease in

special populations. Am J Hypertens 18:S106-S111, 2005

(suppl s)

12. Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Meigs JB, Wilson

PWF, Levy D: Glycemic status and development of kidney

disease. Diabetes Care 28:2436-2440, 2005

13. Norris KC, Agodoa LY: Unraveling the racial dispari-

ties associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int 68:914-924,

2005

14. Rule AD, Jacobsen SJ, Schwartz GL, et al: Acompari-

son of serumcreatinine-based methods for identifying chronic

kidney disease in hypertensive individuals and their siblings.

Am J Hypertens 19:608-614, 2006

15. Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Levy

D, Fox CS: Cardiovascular disease risk factors in chronic

kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 166:1884-1891, 2006

16. Vupputri S, Sandler DP: Lifestyle risk factors and

chronic kidney disease. Ann Epidemiol 13:712-720, 2003

17. Cohn JN, Quyyumi AA, Hollenberg NK, Jamerson

KA: Surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease: Func-

tional markers. Circulation 109:31-46, 2004

18. Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Jhangri GS, Curhan G:

Biomarkers of inammation and progression of chronic

kidney disease. Kidney Int 68:237-245, 2005

19. Stenvinkel P: Newinsights on inammation in chronic

kidney disease-Genetic and non-genetic factors. Nephrol

Ther 2:111-119, 2006

20. Shultis WA, Weil EJ, Looker HC, et al: Effect of

periodontitis on overt nephropathy and end-stage renal dis-

ease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30:306-311, 2007

21. Saremi A, Nelson RG, Tulloch-Reid M, et al: Peri-

odontal disease and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes

Care 28:27-32, 2005

22. Kshirsagar AV, Moss KL, Elter JR, Beck JD, Offen-

bacher S, Falk RJ: Periodontal disease is associated with

renal insufciency in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communi-

ties (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 45:650-657, 2005

Periodontal Disease and CKD 51

23. Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, et al: The

Chronic Renal Insufciency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design

and method. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:S148-S153, 2003 (suppl

2)

24. Cazzavillan S, Ratanarat R, Segala C, et al: Inamma-

tion and subclinical infection in chronic kidney disease: A

molecular approach. Blood Purif 25:69-76, 2007

25. Phipps KR. Stevens VJ: Relative contribution of

caries and periodontal disease in adult tooth loss for an

HMO dental population. J Public Health Dent 55:250-252,

1995

26. Loos BG: Systemic markers of inammation in peri-

odontitis. J Periodontol 76:2106-2115, 2005

27. Offenbacher S, Beck JD: A perspective on the poten-

tial cardioprotective benets of periodontal therapy. Am

Heart J 149:950-954, 2005

28. Slade GD, Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Heiss G, Pankow

JS: Acute-phase inammatory response to periodontal dis-

ease in the US population. J Dent Res 79:49-57, 2000

29. Tonetti MS, DAiuto F, Nibali L, et al: Treatment of

periodontitis and endothelial function. NEngl J Med 356:911-

920, 2007

30. Demmer RT, Desvarieux M: Periodontal infections

and cardiovascular disease: The heart of the matter. J Am

Dent Assoc 137:S14-S20, 2006 (suppl 2)

31. Beck JD, Offenbacher S: Systemic effects of periodon-

titis: Epidemiology of periodontal disease and cardiovascu-

lar disease. J Periodontol 76:2089-2100, 2005

32. Tonelli M, Pfeffer MA: Kidney disease and cardiovas-

cular risk. Ann Rev Med 58:123-139, 2007

33. National Center for Health Statistics: National Health

and Nutrition Examination Survey III Documentation, Code-

book, and Data Files. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

about/major/nhanes/datalink.htm#NHANESIII. Accessed

August 14, 2007

34. Coresh J, Astor BC, McQuillan G, et al: Calibration

and random variation of the serum creatinine assay as

critical elements of using equations to estimate glomerular

ltration rate. Am J Kidney Dis 39:920-929, 2002

35. Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Tilashalski KR: Smokeless

tobacco and severe active periodontal disease, NHANES III.

J Dent Res 84:705-710, 2005

36. Pirkle JL, Flegal KM, Bernert JT, Brody DJ, Etzel

RA, Maurer KR: Exposure of the U.S. population to environ-

mental tobacco smoke. JAMA275:1233-1240, 1996

37. Shah B, Barnwell B, Bieler G: SUDAAN Users

Manual, Release 8.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research

Triangle Institute, 2001

38. Borrell LN, Papapanou PN: Analytical epidemiology

of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 32:S132-S158, 2005

(suppl 6)

39. Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Shelton BJ, Debanne SM:

Sociodemographic characteristics and diabetes predict in-

valid self-reported non-smoking in a population-based study

of U.S. adults. BMC Public Health 7:33, 2007. Available at

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/7/33. Accessed

November 13, 2007

40. US Department of Health and Human Services: The

Health Benets of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the

Surgeon General. Rockville, MD, US Department of Health

and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Pre-

vention, 1990

41. Rahman M, Pressel S, Davis BR, et al: Renal out-

comes in high-risk hypertensive patients treated with an

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or a calcium chan-

nel blocker vs a diuretic. Arch Intern Med 165:936-946,

2005

Fisher et al 52

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Journal - Liver Disease Focus On Ascites PDFDokumen2 halamanJournal - Liver Disease Focus On Ascites PDFTriLightBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatrics MnemonicsDokumen11 halamanPediatrics MnemonicsIndrajit Rana95% (21)

- MCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003 PDFDokumen30 halamanMCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003 PDFrekha meenaBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Paper ASAT X PDFDokumen17 halamanSample Paper ASAT X PDFanurag680% (1)

- 15 Virusne Infekcije U Trudnoci - PrevedenoDokumen7 halaman15 Virusne Infekcije U Trudnoci - PrevedenoVelibor StankovićBelum ada peringkat

- Microbiology Course FileDokumen41 halamanMicrobiology Course FileRavi IndraBelum ada peringkat

- Week-12 VirologyDokumen8 halamanWeek-12 VirologyAlex LiganBelum ada peringkat

- Bovi-Shield Gold FP 5 VL5Dokumen2 halamanBovi-Shield Gold FP 5 VL5טורו קוראזוןBelum ada peringkat

- Hair CareDokumen8 halamanHair CareNeelofur Ibran Ali100% (4)

- Managing Infectious Health Hazards and Diseases in The Construction Industry - SlidesDokumen126 halamanManaging Infectious Health Hazards and Diseases in The Construction Industry - SlidesHuzaifa SafdarBelum ada peringkat

- Pgi May 2012 Ebook PDFDokumen50 halamanPgi May 2012 Ebook PDFloviBelum ada peringkat

- Mnemonic For PharmaDokumen4 halamanMnemonic For PharmaFershell SiaoBelum ada peringkat

- Physical Therapy ReviewDokumen4 halamanPhysical Therapy Reviewpearl042008100% (1)

- Hla IgDokumen48 halamanHla Igprakas44Belum ada peringkat

- Enterobacter Spp.Dokumen32 halamanEnterobacter Spp.ntnquynhpro100% (1)

- 35-1404729796 JurnalDokumen3 halaman35-1404729796 JurnalNancy ZhangBelum ada peringkat

- NematodesDokumen10 halamanNematodesNicolette Go100% (1)

- Canine - Leptospirosis Marge PoughDokumen1 halamanCanine - Leptospirosis Marge Poughw00fBelum ada peringkat

- ChromID CPS Brochure Final-1Dokumen2 halamanChromID CPS Brochure Final-1horia96Belum ada peringkat

- Hand HygieneDokumen3 halamanHand Hygieneashlyn0203Belum ada peringkat

- The Order OnygenalesDokumen24 halamanThe Order Onygenalesnevin100% (1)

- Obstetrics Evidence-Based Algorithms, 2016Dokumen351 halamanObstetrics Evidence-Based Algorithms, 2016stase anak80% (5)

- Viral Infections of The Gastrointestinal Tract and Viral Infections of The Genitourinary SystemDokumen14 halamanViral Infections of The Gastrointestinal Tract and Viral Infections of The Genitourinary SystemDARLENE CLAIRE ANDEZABelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of ZITRITIDEDokumen16 halamanEvaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of ZITRITIDEednisoBelum ada peringkat

- ImmunoSeroLab M4Dokumen3 halamanImmunoSeroLab M4ela kikayBelum ada peringkat

- The Vaccination Controversy The Rise, Reign and Fall of Compulsory Vaccination For SmallpoxDokumen273 halamanThe Vaccination Controversy The Rise, Reign and Fall of Compulsory Vaccination For Smallpoxjamie_clark_2100% (2)

- Lane J 1953 - Neotropical Culicidae Vol IDokumen550 halamanLane J 1953 - Neotropical Culicidae Vol IDavid Schiemann100% (3)

- ROTAVIRUSDokumen13 halamanROTAVIRUSAsma HossainBelum ada peringkat

- Public Health Surveillance-BHWDokumen73 halamanPublic Health Surveillance-BHWPaul Angelo E. CalivaBelum ada peringkat

- Respiratory ReflectionDokumen2 halamanRespiratory ReflectionJennalyn Padua SevillaBelum ada peringkat