Self Esteem On Gender

Diunggah oleh

danieljohnarboleda0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

45 tayangan16 halamanb

Judul Asli

Self Esteem on Gender

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

RTF, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inib

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai RTF, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

45 tayangan16 halamanSelf Esteem On Gender

Diunggah oleh

danieljohnarboledab

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai RTF, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 16

Gender-Role Identity and Self-Esteem

Pamela Frome & Jacquelynne Eccles

University of Michigan

Poster presented at the biannual meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence,

March 7, 1996, Boston, MA. This research has been funded by grants from NIMH,

NSF, and NICHD to Jacquelynne Eccles and by grants from NSF, the Spencer

Foundation and the W. T. Grant Foundation to Jacquelynne Eccles and Bonnie

Barber. The authors would like to thank the following people for their assistance over

the years: Bonnie Barber, Andrew Fuligni, Debbie Jozefowicz, Lisa Colarossi, Kathy

Houser, and Amy Arbreton. Inquiries can be addressed to the frst author at 5201

Institute for Social Research, P.O. Box 1248, 426 Thompson St., Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

Please do not cite without permission.

ABSTRACT

James (1890) hypothesized that individuals base their self-esteem on

performance only in domains of importance to them. This theory would predict

that the relationship between one

'

s gender-role identity and one's self-esteem

should be dependent on the importance one places on masculinity and femininity.

In addition, it is predicted that the self-perception that one is not conforming to

societal gender-role norms will result in lowered self-esteem (sex-role strain). In

this study we examine the relation between gender-role identity and self-esteem,

and the relation between the interaction of gender-role identity and the value of

masculinity and femininity on self-esteem.

Results show a small, but signifcant, main efect of gender-role identity on

self-esteem. Perceiving oneself as feminine was positively related to self-esteem for

females and perceiving oneself as masculine was positively related to self-esteem for

males. There was also a small, but signifcant, interaction efect such that for cross-

typed females valuing the cross-typed gender role and devaluing the traditionally

gender-congruent role was associated with higher self-esteem. This results was not

found, however, for cross-typed males. For gender-congruent-typed males, devaluing

the cross-typed role and valuing the gender-congruent role was assciated with

higher self-esteem.

INTRODUCTION

Research has found that gender-role identity (for this paper defned as the

degree to which one perceives oneself as being masculine or feminine; McNeill &

Petersen, 1985) is linked to self-esteem (Baruch & Barnett, 1975; Broverman, Vogel,

Broverman, Clarkson, & Rosenkrantz, 1972; Kleinplatz, McCarrey & Kateb, 1992),

although the results have not been consistent as to how these two constructs are

linked. At frst it was theorized that women who are. high -M femininity should have

the highest self-esteem (congruence model; Whitely, 1983); it was later hypothesized

that androgynous women or women high in masculinity should have the highest self-

esteem (androgyny and masculinity models; Bem, 1974; Lamke, 1982; Massad, 1981;

Spence, 1983; Whitley, 1983).

However, the scales that have traditionally been used in gender-role identity

research (Personality Attributes Questionnaire, Spence & Helmreich, 1978; Bern Sex

Role Inventory, Bern,1974) only assess the traits of instrumentality and expressiveness

and do not necessarily measure all the domains that are covered under the terms

"

femininity" and

"

masculinity" (Deaux, 1984; Deaux & Lewis, 1984). (Femininity and

masculinity are defned here as socially-defned sex appropriate traits, attitudes,

interests, appearance, and behaviors; Pleck, 1982). These scales use only the domain of

personality traits to defne femininity and masculinity and do not include other possible

aspects of gender-role identity such as physical appearance, role behaviors, and

occupations (Deaux, 1984; Deaux & Lewis, 1984; Spence, 1983; Whitley, 1983).

In addition, these studies do not account for individual within-gender

diferences in the relation between gender-role values and self-esteem (see Bern, 1981

and Markus, Crane, Bernstein & Siladi, 1982 for a discussion of individual diferences

regarding self-schemas and gender). According to James (1890), individuals base their

self-esteem on their performance only in domains of importance. Support for this

theory has been found by Harter (1993) in the domains of school, athletics, social

ability, behavioral conduct, and physical appearance. Thus, in the domain of gender

roles, one's gender-role identity should infuence self-esteem only to the degree that

this identity is valued by the individual.

4

However, other researchers have proposed that since the norms of one's gaup

(for example societal prescriptives that females should be feminine and males should

be masculine) become internalized by the individual, group values will be infuential in

determining an individual's ratings of the importance of a domain (Coopersmith,

1967). Failing to meet expectations in a domain deemed important by society could

lead to negative psychological consequences. For example, the negative efects

(specifcally low self-esteem) of not conforming to larger societal sex role norms has

been referred to as sex role strain (Eccles & Bryan, 1994; Garnets & Pleck, 1979).

Pelham (1995) posits that it appears that while group norms are important in the

relation between self-views and self-esteem, individual diferences in ratings of

importance of domains also infuence this relation. Thus, while group norms should

impact the infuence of gender-role identity on self-esteem, individual diferences in

the amount of importance placed on fulflling the gender role norms should also

infuence self-esteem.

Since masculinity and femininity are by defnition one prescribed gender-role

identity for the respective genders, we predict that for females, self-perceptions of

femininity will be positively correlated with self-esteem and that for males, self-

perceptions of masculinity will be positively correlated with self-esteem. In addition,

we predict that an interaction will occur such that the more importance the individual

places on their own gender-role identity and the less importance they place on the

gender-role identity with which they do not identify, the higher their self-esteem will

be.

METHODS

The data for this research are part of a longitudinal investigation, the

Michigan Study of Adolescent Life Transitions (P.I.s Jacquelynne Eccles and Bonnie

Barber). The data reported here were collected during the participants' sophomore

year in high school. Approximately 685 females and 530 males were included in

these analyses. The students in this study are primarily European-American and

come from low- to middle-income communities.

The gender role identity scale was made up of three items, "I feel as though I

am if...", "I appear as though I am..." and "Other people see me as...", that were

answered on a 7-point Likert scale anchored at the low end (1) with

"

very masculine"

and at the high end (7) with "very feminine" (alpha=.97, this is a modifed version of

the Sexual Identity Scale; Stern, Barak, & Gould, 1987). The value of masculinity was

measured by the question,

"

How important it is to you to engage in activities that make

you appear masculine?", answered on a 7-point Likert scale anchored at the low end (1)

with

"

not at all important" and the high end (7) with "very important". The value of

femininity was measured by the question, "How important it is to you to engage in

activities that make you appear feminine?", answered on a 7-point Likert scale

anchored at the low end (1) with

"

not at all important" and the high end (7) with "very

important".

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Due to the fact that there is a societal norm/value for females to be feminine

and for males to be masculine, it was hypothesized that a feminine gender-role

identity would have a positive relation to self-esteem for females and that a

masculine gender-role identity would have a positive relation to self-esteem for

males. This hypothesis was supported: for females, there was a signifcant positive

correlation between gender role identity and self-esteem (r=.22, p <.001), and for

males, there was a signifcant negative correlation between the measure of gender-

role identity and self-esteem (r=-.20, p<.001 (since a more masculine gender-role

identity is coded at the low end of the scale the negative correlation represents a

positive relationship).

Separate hierarchical regression analyses for females and males showed that

gender-role identity on average explained 5% of the variance in self-esteem. There was a

positive main efect of gender-role identity on self-esteem such that females with more

feminine gender-role identities had higher self-esteem, while males with more

masculine gender-role identities had higher self-esteem (see Table 1). These fndings

support the idea that there is a general societal value placed on females being feminine

and males being masculine such that masculinity/femininity predict somewhat to self-

esteem, although they explain only a small amount of the variance. These fndings also

support the congruence hypothesis, which posits that individuals with a gender-

congruent identity will have higher self-esteem than those with a cross-typed identity.

There was an unpredicted main efect of the value of masculinity for males, such that,

when controlling for gender-role identity, placing a high value on masculinity predicted

self-esteem (see Table 1).

The interaction between gender-role identity and the value of masculinity and

femininity was signifcant (except for value of masculinity for boys), explaining an

additional 1% to 2% of the variance in self-esteem (see Table 1). For females, the

interaction hypothesis was partially supported. Masculine-typed females who valued

masculinity and those who devalued femininity had higher self-esteem than those

who devalued masculinity and valued femininity (see Figures 1 & 2). However, the

predicted interaction for feminine-typed females was not found. There were no self-

esteem diferences among feminine-typed females based on their value of masculinity

and femininity.

The interaction hypothesis was also partially supported for males. Masculine-

typed males who valued masculinity and those who devalued femininity had higher

self-esteem than those who devalued masculinity and valued femininity (see Figures 3

& 4). However, the interaction hypothesis was not supported for feminine-typed males.

For feminine-typed males, the value of femininity did not

8

infuence self-esteem, and contrary to predictions, those adolescents who valued

masculinity had higher self-esteem than those who devalued masculinity.

Thus, an interesting between-gender efect emerged; for cross-typed females

valuing the cross-typed gender role was associated with increased self-esteem, but not

for cross-typed males. In addition, for gender congruent-typed males, devaluing the

cross-typed role was associated with increased self-esteem, but not for gender

congruent-typed females. It appears that the pressure for males to avoid the feminine

gender-role is so extreme that for feminine-identifed males valuing femininity (and

devaluing masculinity) is not associated with higher self-esteem. This efect could be

due to an overall societal valuing of masculinity and devaluing of femininity (especially

for males), such that even though some feminine-identifed males valued femininity

they may have perceived that others do not value femininity and so their own value of

femininity was not a strong enough factor to allow their self-perception of femininity to

contribute to their self-esteem. Whereas, it seems that the pressure for girls to avoid

masculinity exists (refected by the results that feminine-identifed females have higher

self-esteem than masculine-identifed females), but is somewhat less extreme that the

pressure for

males to avoid femininity since masculine-identifed females who value

masculinity have higher self-esteem than those who do not.

Future research should explore the meaning of the words

"

masculine" and

"feminine" for adolescents. It has been proposed that gender-role identity is a

multidimensional construct (for example, in an adult samples femininity has been

found to include: expressive characteristics, social roles, emotional dependency, and

independence; in an adult sample, masculinity has been found to include:

instrumental qualities, social roles, and job performance; Spence & Sawin, 1985).

Thus, it is difcult to know exactly what the adolescent participants in the current

study have in mind when rating themselves on gender-role identity. Perhaps the

relationship between gender-role identity and self-esteem would be better

understood treating gender-role identity as a multidimensional construct,

specifcally naming the dimensions of which it is composed.

References

Baruch, G. & Barnett, R. (1975). Implications and applications of recent research on

feminine development. Psychiatry, 38 318-327.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 4g, 155-162.

Bem, S.L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing.

Psychological Review, 8$ 354-364.

Broverman, I., Vogel, S., Broverman, D., Clarkson, F., & Rosenkrantz, P. (1972).

Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Tournal of Social Issues, 10, 399-407.

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco, CA: W.H.

Freeman & Co.

Deaux, K. (1984). From individual diferences to social categories. American

Psychologist, 39 105-116.

Deaux, K. & Lewis, L. (1984). Structure of gender-stereotypes: Interrelationships

among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

46, 991-1004.

Eccles, J. & Bryan, J. (1994). Adolescence: Critical crossroad in the path of gender-

role development. In M. R. Stevenson (Ed.), Gender Roles Through the Life Span.

Muncie, Indiana: Ball State University.

Garnets, L. & Pleck, J. (1979). Sex role identity, androgyny, and sex role

transcendence: A sex role strain analysis. Psychology of Women Ouarterly, 3 270-

283.

Harter , S. (1993). Causes and consequences of self-esteem in children and

adolescents. In R.F. aumeister (!d.), Self-!steem" the #u$$le of lo% self-re&ard.

'e% (or)" *lenum.

+ames, ,. (1-9.). /he #rinci#les of #s0cholo&0. 'e% (or)"Holt.

1lein#lat$, *., 2cCarre0, 2., 3 1ate4, C. (1995). /he im#act of &ender-role

identit0 on %omen6s self-esteem, lifest0le satisfaction and conflict. Canadian

+ournal of eha7ioural Science, 58 333-389.

:am)e, :. (19-5). /he im#act of se;-role orientation on self-esteem in earl0

adolescence. Child <e7elo#ment, =3, 1=3.-1=3=.

2ar)us, H., Crane, 2., ernstein, S. 3 Siladi, 2. (19-5). Self-schemas and

&ender. +ournal of *ersonalit0 and Social *s0cholo&0, 85 3--=..

2assad, C. (19-1). Se; role identit0 and ad>ustment durin& adolescence. Child

<e7elo#ment, =5 159.-159-.

2c'eill, S. 3 *etersen, ?. (19-=). @ender role identit0 in earl0 adolescence"

Reconsideration of theor0. ?cademic *s0cholo&0 ulletin, 1 559-31=.

*elham, . ,. (199=). Self-in7estment and self-esteem"!7idence for a +amesian

model of self-%orth. >ournal of *ersonali t0 and Social *s0cholo&0, A9 1181-11=..

Flec), +. H. (19-5). /he m0th of masculinit0. Cam4rid&e, 2?" /he 2I/ *ress.

S#ence, +./. (19-3). Comment on :u4ins)i, /elle&en, and utcher6s

B

2asculinit0,

Femininit0, and ?ndro&0n0 Cie%ed and ?ssessed as <istinct Conce#tsB. +ournal of

*ersonalit0 and Social *s0cholo&0, 88 88.-88A.

S#ence, +. /. 3 Helmreich, R. :. (199-). 2asculinit0 and femininit0" /heir

#s0cholo&ical dimensions, correlates, and antecedents. ?ustin" Dni7ersit0 of /e;as

*ress.

S#ence, +. /. 3 Sa%in, :. :. (19-=). Ima&es of masculinit0 and femininit0" ?

reconce#tuali$ation. In C. E

6

:ear0, R. Dn&er, . ,allston (!ds.) ,omen, &ender, and

social #s0cholo&0. Hillsdale, 'e% +erse0" :a%rence !rl4aum ?ssociates.

11

10

Stem, B., Barak, B., & Gould, S. (1987). Sexual Identity Scale: A New Self-

Assessment Measure. Sex Roles, 17, 503-519. -

Whitley, B., Jr. (1983). Sex Role Orientation and Self-Esteem: A Critical Meta-

Analytic Review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44 765-778.

Table I. Infuence of Gender-Role

Identity. and Value of Gerider-

Role on Self-Esteem

Female

s

B

R

Squar

Step 1 gender-role

identity

.04 .05***

Step 2 interaction -.07 01***

otal R Square .0!***

Step 1 gender-role

identity

"alue o#

#emrnininty

interaction

$$**

*

-.05

%ales B

R

Square

Step

1

gender-role

identity

.0&** .05**

Step 2 interaction .01 .00

otal R Square 05**

Step 1

gender-role

identity

-.25**

*

"alue o# -.0! 04***

Step 2 interaction .10*** 02***

otal R Square .0!***

Figure 1. Females-Importance of Femininity

5. 5

5,3

5.1

4.9 /

4,7 4.5

4.3 4.1

3.9 3.7

3.5

masculin

e

femininity

not

important

femininity important

neither

mascline

nor

feminine

feminine

gender-role identity

Figure 2. Females- Importance of Masculinity

masculine neither feminine

masculine

nor

feminine

gender-role identity

masculinity

not important

masculinit

y

important

5.5

5.3

5.1

4.9

4.7

4.5

4.3

4.1

3.9

3.7

3.5

Figure 3. Mates-Importance of

Femininity

5.2

4.8 _ -

femininity not

important

4.6

- -

- femininity

4,4 important

4.2

4 a__________

masculine

neither

masculine

nor

feminine

feminine

gender-role identity

Figure 4. Males- Importance of Masculinity

masculinity not

important

- - - masculinity

important

4

masculine neither feminine

masculine

nor

feminine

gender-role identity

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- College Differences in PS FEB 5Dokumen2 halamanCollege Differences in PS FEB 5danieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- 3RD StudyDokumen3 halaman3RD StudydanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- HUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in Applied Social Sciences CGDokumen7 halamanHUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in Applied Social Sciences CGdanieljohnarboleda100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Introduction To The WAIS IIIDokumen16 halamanIntroduction To The WAIS IIIdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Se Per College 1 LaDokumen2 halamanSe Per College 1 LadanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- LOCAL STUDIES Self-Esteemfeb 1Dokumen5 halamanLOCAL STUDIES Self-Esteemfeb 1danieljohnarboleda62% (13)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- SLCS RDokumen2 halamanSLCS RdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- LOCAL STUDIES Self-Esteemfeb 1 RevisedDokumen3 halamanLOCAL STUDIES Self-Esteemfeb 1 Reviseddanieljohnarboleda56% (9)

- 1 John 1Dokumen1 halaman1 John 1danieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Job Order ImcDokumen2 halamanJob Order ImcdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Music Year IIDokumen1 halamanMusic Year IIdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Postwar Tension: Truman's Postwar VisionDokumen7 halamanPostwar Tension: Truman's Postwar VisiondanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Syl Oct2002-DownloadDokumen2 halamanSyl Oct2002-DownloaddanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Building Up: Homeward Bound!!Dokumen2 halamanBuilding Up: Homeward Bound!!danieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Tuition RatesDokumen1 halamanTuition RatesdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Perception Developed by German Psychologists in The 1920s. These Theories Attempt To Describe HowDokumen8 halamanPerception Developed by German Psychologists in The 1920s. These Theories Attempt To Describe HowdanieljohnarboledaBelum ada peringkat

- Foucault, M.-Experience-Book (Trombadori Interview)Dokumen11 halamanFoucault, M.-Experience-Book (Trombadori Interview)YashinBelum ada peringkat

- Fix List For IBM WebSphere Application Server V8Dokumen8 halamanFix List For IBM WebSphere Application Server V8animesh sutradharBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- TTPQDokumen2 halamanTTPQchrystal85Belum ada peringkat

- ENTRAPRENEURSHIPDokumen29 halamanENTRAPRENEURSHIPTanmay Mukherjee100% (1)

- Is Electronic Writing or Document and Data Messages Legally Recognized? Discuss The Parameters/framework of The LawDokumen6 halamanIs Electronic Writing or Document and Data Messages Legally Recognized? Discuss The Parameters/framework of The LawChess NutsBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Prof. Monzer KahfDokumen15 halamanProf. Monzer KahfAbdulBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Fort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónDokumen90 halamanFort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónEvelin PalenciaBelum ada peringkat

- CRM Final22222222222Dokumen26 halamanCRM Final22222222222Manraj SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Diva Arbitrage Fund PresentationDokumen65 halamanDiva Arbitrage Fund Presentationchuff6675Belum ada peringkat

- ANSI-ISA-S5.4-1991 - Instrument Loop DiagramsDokumen22 halamanANSI-ISA-S5.4-1991 - Instrument Loop DiagramsCarlos Poveda100% (2)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Topic 6Dokumen6 halamanTopic 6Conchito Galan Jr IIBelum ada peringkat

- Branding Assignment KurkureDokumen14 halamanBranding Assignment KurkureAkriti Jaiswal0% (1)

- Durst Caldera: Application GuideDokumen70 halamanDurst Caldera: Application GuideClaudio BasconiBelum ada peringkat

- 1INDEA2022001Dokumen90 halaman1INDEA2022001Renata SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- UXBenchmarking 101Dokumen42 halamanUXBenchmarking 101Rodrigo BucketbranchBelum ada peringkat

- Death and The King's Horseman AnalysisDokumen2 halamanDeath and The King's Horseman AnalysisCelinaBelum ada peringkat

- BCG-How To Address HR Challenges in Recession PDFDokumen16 halamanBCG-How To Address HR Challenges in Recession PDFAnkit SinghalBelum ada peringkat

- KV3000 Programming TutorialDokumen42 halamanKV3000 Programming TutorialanthonyBelum ada peringkat

- Amt 3103 - Prelim - Module 1Dokumen17 halamanAmt 3103 - Prelim - Module 1kim shinBelum ada peringkat

- 059 Night of The Werewolf PDFDokumen172 halaman059 Night of The Werewolf PDFomar omar100% (1)

- Green Campus Concept - A Broader View of A Sustainable CampusDokumen14 halamanGreen Campus Concept - A Broader View of A Sustainable CampusHari HaranBelum ada peringkat

- Astm D1895 17Dokumen4 halamanAstm D1895 17Sonia Goncalves100% (1)

- Finding Neverland Study GuideDokumen7 halamanFinding Neverland Study GuideDean MoranBelum ada peringkat

- BSBHRM405 Support Recruitment, Selection and Induction of Staff KM2Dokumen17 halamanBSBHRM405 Support Recruitment, Selection and Induction of Staff KM2cplerkBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Commercial Private Equity Announces A Three-Level Loan Program and Customized Financing Options, Helping Clients Close Commercial Real Estate Purchases in A Few DaysDokumen4 halamanCommercial Private Equity Announces A Three-Level Loan Program and Customized Financing Options, Helping Clients Close Commercial Real Estate Purchases in A Few DaysPR.comBelum ada peringkat

- Pasahol-Bsa1-Rizal AssignmentDokumen4 halamanPasahol-Bsa1-Rizal AssignmentAngel PasaholBelum ada peringkat

- Dragon Ball AbrigedDokumen8 halamanDragon Ball AbrigedAlexander SusmanBelum ada peringkat

- Type of MorphologyDokumen22 halamanType of MorphologyIntan DwiBelum ada peringkat

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University VisakhapatnamDokumen6 halamanDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University VisakhapatnamSuvedhya ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- Fix Problems in Windows SearchDokumen2 halamanFix Problems in Windows SearchSabah SalihBelum ada peringkat

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateDari EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HatePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (18)

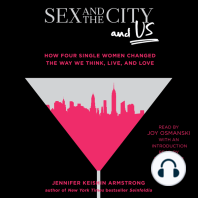

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveDari EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LovePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (22)