History of Cresswell's Roman Catholic Community

Diunggah oleh

Jon Smith100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

339 tayangan9 halamanLocal history

Judul Asli

Cresswell History Staffs UK

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniLocal history

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

339 tayangan9 halamanHistory of Cresswell's Roman Catholic Community

Diunggah oleh

Jon SmithLocal history

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 9

A Short History of

Cresswells Roman Catholic

Community

Philip Bailey S.C.J.

A Short History of Cresswells Roman Catholic Community

Philip Bailey S.C.J.

i

The township of Cresswell can boast of one feature which is rather unusual in England: most of our

villages and hamlets have at least one place of worship, Anglican or Wesleyan, but there are very few

places which have only a Roman Catholic church. The reason for this is because Roman Catholicism has

managed to survive in this part of the parish of Draycott-le-Moors since pre-Reformation times. Its

survival was due mainly to the fact that the Draycott family, who owned most of the land around

Cresswell, never conformed to the Church of England.

From early medieval times the Draycotts were lords of the manor of Draycott, Painsley, Fewton

and Cumshall; in the reign of Henry VIII Sir Philip Draycott also possessed lands in Alstonfield, Warslow,

Butterton, Kingsley, Broddock, Whiston and Leigh. In 1853 the Draycotts' successors owned over two

thousand acres in the parish of Draycott. Such a powerful feudal position naturally gave them a great

influence over their tenants in Draycott, Cresswell and the neighbouring hamlets.

ii

Just before the Reformation a William Draycott, brother of the Lord of the Manor, was parish priest

of St. Margarets, Draycott. There is a copy of his will in the church; it provides for a dole to be distributed

on certain days of the year, to the poorest households within Draycott parish. William Draycotts

nephew, Anthony, son of his brother Sir John, also became a priest. After a distinguished academic career

in the University of Oxford, he received many ecclesiastical preferments, among them the rectorship of

Checkley. The church there still has some items showing his connection with the place; there are bench

ends carved with the rectors initials, A.D. (Anthony Draycott), a dragons head (a family symbol, draco ~

Latin for dragon), and the Draycott coat of arms. On the medieval stained glass window at the east end

of the church there is the inscription Draycot finis Anthon., which probably means that Anthony

Draycott was also responsible for the window.

At the Reformation Anthony Draycott and his brother Philip, who became lord of the manor in

1523, refused to conform to the new Anglican religion. Anthonys career as a churchman was only

gradually affected by the religious changes which took place during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI,

Mary Tudor and Elizabeth I. In common with the majority of the English clergy, Draycott seems not to

have had any scruples about the Oath of Supremacy, declaring the King to be the head of the Church

because, during Henry VIIIs reign, he held various ecclesiastical offices. When Edward became King,

Anthony Draycott still continued to hold positions in the Church. However, in view of his antipathy

towards Protestants during the reign of Mary Tudor, it is extremely unlikely that he favoured the

Protestant reforms legalised under Edward. When Mary Tudor became Queen in 1553 Draycott, as

Chancellor of the diocese of Lichfield, was involved in the persecution of Protestants. The Protestant

historian Foxe describes in lurid detail Draycotts fanatical treatment of those who could no longer

accept Roman Catholicism; his attitude was typical of many Catholics and Protestants at the Reformation;

it was a period when both parties felt deeply their religious convictions.

When Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558 Antony Draycott was deprived of all ecclesiastical

offices and imprisoned in the Fleet; this was in 1560. He remained in prison until the last year of his life

when he was allowed to return to Painsley. A fellow-prisoner wrote of him, full of admiration for his

fortitude. He says both Draycott and himself rose from sleep at midnight to pray. Anthony Draycott died

on January 20th 1570 and, according to the brass inscription in St. Margarets church, he was buried

there. Undoubtedly Anthonys decision and fortitude influenced his family to remain loyal to the Church

of Rome.

iii

Sir Philip Draycott had, in 1558, made provision in his will for the continuance of Catholic worship:

there are some references to various items connected with the celebration of mass. Already, as early as

1538, when the monasteries were being dismantled, he had bought several sets of mass vestments, and

in his will he asks that they be kept in his chapel. This chapel was the one at Painsley Hall near Cresswell.

The Draycott family had lived there since 1496, when John Draycott let his olde house downe and

builded in another place of Draucote parish, a goodly house called Painsle. The present ruinous hall is

built on the site of John Draycotts Tudor mansion. A Mr Walter Draycott, who came to Draycott from

Canada in 1911, says he saw an ancient painting of the hall, which was then in the possession of a local

resident. He describes the painting of the hall: the facade (of the hall) had a southern aspect, showing

two tall towers resembling keeps and a high wide doorway between the two towers with a gothic

archway or entrance. The moderately large windows were built in the Tudor style. The whereabouts of

this painting is now unknown.

From the accession of Queen Elizabeth until 1649 Painsley Hall was a centre for Roman Catholic

worship. The Draycotts abandoned the parish church and only used it for burying their dead. The present

vestry at St. Margarets contains many Draycott tombs as well as the graves of some of the priests who

served the Catholics at Cresswell.

iv

Extant records tell us about Roman Catholic recusancy in Draycott parish from the reign of Queen

Elizabeth until the anti-Catholic penal laws were repealed between 1791 and 1829. (So, when Elizabeth

was journeying through Staffordshire in 1575 she had John Draycott and several other gentlemen from

the county arrested. They were charged that they went not to church, and confessing the same, and

alledging their consciences and the examples of their forefathers who taught them so. However, in

fairness to the queen, it must be said that her real motive for this was political rather than religious: at

this time Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned in the area. Elizabeth regarded her as a potential rival to

the English throne and many Roman Catholics were prepared to further the Scottish queens claim.)

Hence Elizabeth would feel safer with the Staffordshire Catholic Squires in prison. Nor were her fears

groundless, for Anthony Babbington, a Derbyshire nobleman, married to Margery Draycott, plotted with

a group of Catholics to release Mary from Chartley Castle not far from Painsley; the conspirators were led

into a trap and executed at Tyburn in 1586.

Already, in 1561 a John Draycott had been arrested. In a letter to the Privy Council it was stated:

we are informed that through the example of two Derbyshire gentlemen and John Draycott Esq., being

by us committed to prison and through the bearing and supporting of their wives, kinsfolk, allies and

servants, a great part of the shires of Stafford and Derby are generally evilly inclined towards religion and

forbear coming to church and participating of the Sacraments, using also very broad speeches in

alehouses and elsewhere, and therefore your honours may it please you to have special regard to these

parts.

In 1607, besides the lord of the manor of Draycott, thirty of his tenants in Leigh and seventeen in

Draycott parish were recusants. In 1629, when the Bishop of Lichfield visited Draycott, he complained

that popish recusants were burying their dead in William Lathams field. In 1641 there were twenty six

recusants recorded at Draycott. These numbers represent only the heads of households In the list of

recusants for 1607 a John Warrilow is mentioned, and in the list for 1641 a Charles Fielding is named:

there were still Catholics with the names Fielding and Warrilow at Cresswell in living memory.

v

Between 1649 and 1660 the future of the Roman Catholic community in Cresswell district became

uncertain. This was due to the Civil War between the followers of Charles I and Cromwell. Like most of his

Catholics, the lord of the manor of Draycott and his tenants supported the King. According to the records

only three men from Draycott parish followed Cromwell, whereas at Tean, then a much smaller place,

there were twelve men who volunteered to join forces with the Parliament.

As a result of his loyalty to Charles I, Philip Draycotts manor at Draycott and Painsley was

sequestered by the Roundheads. A colonel named Ashenhurst was deputed to garrison the Hall and

collect rents from the estate for the Parliamentary cause. Ten soldiers were quartered at Painsley and

another detachment at Caverswall Castle. The local Catholic recusants were singled out for special

spoliation, a warrant being issued to authorise seizure of any corn belonging to recusants and

delinquents; at Draycott both titles referred to the same people: Roman Catholics. Ashenhurst, with

typical puritanical zeal, made repeated searches at Painsley Hall for the church furniture and vestments

which he believed had been hidden before his troops arrived; in fact the vestments were discovered over

two hundred years later.

On March 2nd 1644 the Parliamentary committee at Stafford sent word to the local commanding

officer to render Painsly House unserviceable' . On March 11th the committee complained that its order

to demolish the place had not yet been carried out by Major Ashenhurst. Finally, the ancient manor

house of the Draycotts was destroyed. The Draycott manuscript records the tradition of its destruction as

it was preserved and related by Mr J Wright in 1911: Cromwell took away a lot of the old building stone

and timbers after they had destroyed the mansion. Cromwell also took away furniture, carts, horses,

cattle and other livestock. The menfolk who had defended Painsley were taken away to Stafford as

prisoners. This family tradition seems a reasonable account because the only apparent remains of the

Tudor Painsley Hall are the large stone chimney and a wainscoted room. This catastrophe for the

Draycotts and their tenants might have seen the end of the Roman Catholic community around Cresswell

but for several factors. By 1644 the papist cause had flourished around Cresswell for a hundred years;

when Charles II became King in 1660 the Draycott family rebuilt the family seat on a modest scale; and,

most important of all, Cresswell was now recognised by the English Roman Catholic authorities as an

influential Catholic centre in the Midlands. Because of these factors the Cresswell congregation could be

certain of a resident priest.

After the death of the Rev Anthony Draycott in 1570 there is no certain evidence that a priest

resided permanently at Painsley. Between 1570 and 1652 there were other Catholic centres besides

Painsley in north Staffordshire. Thus for a time there were Catholic squires at Sandon, Thornbury Hall

(Cheadle), Biddulph and Hilderstone, not to mention the house of the Fowlers at Stafford where the last

Catholic bishop of Peterborough lived after he had been deposed by Queen Elizabeth. It would have

been very unlikely at this time for all these Catholic houses to have a resident priest, situated as they

were within a few miles of each other. During the Elizabethan and Jacobean era the priest probably

served the whole area staying for a time with each of the Catholic squires, with a more or less permanent

residence in one of their houses. We have no definite evidence as to who the priest was in the Cresswell

area between 1570 and 1667, nor do we know his semi-permanent residence. There was a priest living at

Hilderstone on Lord Gerards estate for some time. He died there in 1658; his name was Walter

Luddington. Another priest who had some connection with Cresswell district was Thomas Hodgson, who

was born at Draycott in 1601. In 1617 he was received into the Catholic Church by his uncle, also named

Thomas Hodgson, who was a Jesuit. This nephew became a secular priest and worked in England from

1625 using the name More in order to conceal his identity. Both nephew and uncle may have been

resident priests at Painsley. In fact, we have some slender evidence that the nephew did work around

Cresswell: Walter Draycott copied the following words from an ancient title deed in 1911 ~ F. Mouer

(More?) chap...ne (chaplaine?) Att Paynsl... (Paynsley?)

The possibility of a resident priest living at Painsley before 1667 is further highlighted by the

curious, but as yet unconfirmed evidence, recorded by Walter Draycott mentioned above. The following

account is taken from his typescript in the Salt Library, at Stafford: While staying at the Draycott Arms, it

was my good fortune to meet some old residents. Draycott goes on to say that a Mr Lovatt, who was

then (1911) over seventy, of an old local family, produced some ancient documents, which turned out to

be title deeds. On these documents there was reference to a Father Babbington, described as howse

chaplayne att Paynesley . This Fr. Babbington, the documents said, was passing by the woods near

Cresswell (Rookery Farm?) , with some junior priests, when they were attacked by armed ruffians lying in

ambush (Cromwellian soldiers?). Babbington, who appears to have been known to the gang, was

specially singled out for attack. He made no attempt at resistance and so was instantly killed. The rest of

the party, being unarmed, fled towards Painsley Hall, though not before they had suffered injury in

warding off attacks. An armed force was sent out from Painsley but the murderers had retreated. They

found the head of the priest had been struck off and mounted on a spear driven into the ground.

Sometime after the deed was committed a cross was erected to his memory and the site named

Killcross. The year of the murder was 1650/1, a Richard Lovatt was present in the sortie from Painsley

Hall.

This strange tale poses a number of questions: where is the document from which Draycott

quotes the story? where is Killcross? So far, no ecclesiastical record has been found which mentions a

priest named Babbington. Was he a son of the ill-fated Anthony Babbington, the husband of Margery

Draycott? Further research may one day provide us with an answer to these intriguing questions.

vi

Throughout the period of persecution the Catholic faith was kept alive in England by men and

women who became priests and nuns. The priests, who were trained on the continent, usually returned

to England to work for the rest of their lives. The penalty of the law, if they were discovered, was death.

However, the Draycotts continued to give members of their family to the Church as priests and nuns. It

was customary to make a declaration of faith when a candidate entered a seminary. The following is a

declaration made by one of the Draycotts: My name is George Draycott, alias Parker. I was born in the

county of Salop, but brought up at Painsley in the county of Stafford. I have brothers, sisters and

relations, all Catholics. I made my residential studies at home, but not with much success. I was always a

Catholic and left England at the age of ten. George Draycott made this humble declaration when he

entered the English College at Rome in 1633.

When he refers to his studies at home, it reminds us that Catholic priests were often engaged

ostensibly as tutors. Thus, one of the first priests known to have resided at Painsley was Francis Gage,

who was tutor to the young Philip Draycott from 1667 until 1675. However, during this period, Fr. Gage

accompanied his charge on a continental tour. The reason he was able to do this was because there was

another priest in residence at Painsley; this was Robert Fitzherbert, who had been there since 1652. He

was related to the Draycotts by marriage, his sister Anne having married into the family. Fr. Fitzherbert

was chaplain at Painsley for almost fifty years. In fact, he was an important member of the Churchs

hierarchy, being archdeacon of Staffordshire, Derbyshire and Cheshire. In 1687 there is the first record of

a number of Cresswell Catholics sent by him to Stafford where they were confirmed by Bishop Leyburne,

one of the first Catholic bishops to reside in England after the Reformation. Amongst those confirmed

from the Painsley mission were Mary Catherine Draycott, Jane Fielding, Anne Gallimore, Elizabeth

Hammersley, Thomas Lovatt and Thomas, Williams and John Warrilow.

When Robert Fitzherbert died in 1701 there occurred an incident which illustrates the bitter rivalry

which existed between Catholics and their Protestant relatives. Fr. Fitzherberts Protestant nephews

obtained a court order from the diocesan court in Lichfield allowing them to administer his property,

since he died intestate. His next of kin, his sister Anne, a Catholic, was forced to renounce her claim to

administration. The Roman Catholic clergy were particularly anxious that a certain sum which Fitzherbert

had set aside for their sick members should not be appropriated: there is 100 guineas in gold (at Olton in

ye clergy box) of Mr Robt. Ffitzherbert lately deceased, given to our clergy in general to be remembered

among our benefactors, in case his litigious Prot. nephew does not force it from us, as he has done most

of ye remainder of his uncles concerns.

Between 1652 and the present day there has been an unbroken succession of priests resident in

the Cresswell district. The reason for saying Cresswell district rather than at Painsley is because certain

changes in the Draycott family fortunes occurred during the eighteenth century and, as a result, the

priest did not always live at Painsley itself. However, a number of priests continued to reside at the Hall,

among them Alban Butler who wrote the Lives of the Saints; though he didnt like the area very much.

Walter Fleetwood was there from 1732 to 1735, and it was reported left 1000 to the Cresswell mission

when he died in 1774.

vii

At the end of the 17th century the Draycotts long association with Painsley came to an end.

Before that, there is some evidence to show that the squire may have been involved in the plots to

restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty to the throne. At the Jacobite trials held in Manchester in 1694 a

number of suspected conspirators were said to have been meeting at Philip Draycotts house in Painsley.

It was alleged that he and other like-minded gentlemen were using their houses to store arms to be used

to further the Stuart cause. On this occasion the evidence given could not be proved, however some of

these gentlemen were certainly involved later in the Jacobite invasion of 1715: they were forced to flee

abroad, some were executed. Philip Draycott was not involved because he left England after the trial of

1694 and died four years later on the estate of the Elector of Brandenburgh. This Philip Draycott was the

last, direct, male descendant of the family; his sister Frances joined the Draycott estates with those of

Lord Langdale through her marriage to him. Through him the estate passed to the Stourtons of Yorkshire

and to that branch of the family which took the name Vavasour.

Thus, at the time English Roman Catholics were having their civic rights restored (the penal laws

were repealed between 1778 and 1829) there was no direct descendant of the Draycotts living at

Cresswell. The hall was let out to local tenants and the priest was provided with a house on the estate

since the Langdales, Stoutons and Vavasours were Catholics. While the Rev. Edward Coyney was at

Cresswell an agreement was drawn up between the church authorities and Lord Langdale in which, in

return for an annuity, his lordship would appoint a priest to reside at Painsley or nearby. This latter

provision was probably inserted because Fr. Coyney, a local man from Weston Coyney, had been living

with his relatives at home or with his aunt at Bramshall near Uttoxeter. However, he continued to live at

Bramshall after the agreement was signed so, apparently, it was considered to be near enough to

Painsley and so within the terms of the settlement. When he died in 1772 he was buried at Bramshall, it

was said by his niece Mary Warner that he was obliged to disguise himself as a bagpipe player or a

pedlar in order to gain admittance into Catholic families. Coyneys successor, Thomas Mackworth, was at

Painsley from 1722 until 1726. He had to leave then because of persecution by the parson of Draycott -

the penal laws against priests could still be enforced in 1726. The priests who followed him, however,

were permitted to live in peace either at Painsley, Rookery Farm, Lees Houses, or at the old presbytery in

Cresswell.

viii

The extant records show that the number of Catholics was maintained after the Civil War, at

Cresswell and the surrounding district. The list of Catholic non-jurors for 1715 mentions only property

owners besides Lord Langdale who was not resident. There was, for example, John Coyney of Fole,

Edward How of Leigh and Thomas Lovatt of Draycott; the numerous Catholic tenants were not included

in the list. The number of Papists given for 1767 in Draycott parish was 156: a man aged 54 is the

reputed official priest, many are farmers. There are 4 paupers. The priest referred to was Edward

Granhan who, according to his last will and testament, was a member of the German nation and

Master of Arts in the University of Paris, of Lees Houses in the Parish of Draycott. Judging from the

terms of his will he was probably Irish by birth or adoption since he left a legacy to his brother-in-law in

Dublin; he also made provision for an annuity which shall be for ever employed in having the children of

such poor Catholic parents of the City of Dublin who can not afford it taught to read, write and

particularly instructed in the Christian doctrine.... Edward Granhan died at Cresswell in 1776; his

gravestone in the Draycott chapel at St Margarets has the following text: Underneath this stone lieth

the body of the Revd. Edward Granhan late of Lees House who died April 26th 1776 aged 69 years.

The existing baptismal registers for the years 1780-1841 record 781 baptisms; James Tasker, priest

at Cresswell from 1776 until 1815 baptised 393 children. The names of Cresswell Catholics in these

registers are almost entirely local Staffordshire names. Many are those of Catholic families still associated

with the present parish - for example: Perry, Gosling, Sanders, Shingler, Ridge. The occasional Irish

immigrant is usually mentioned as such; there are only about ten of these - for example: Elizabeth

Goulding, Galway, Ireland. Between the years 1820-1822 there are references to the place of residence:

Tean, Tenford, Totmonslow, Waste Gate. Many children at this time were given Old Testament names in

common with their non-Catholic neighbours: Elijah Dean, Sarah Cope, Hannah Shingler, Rebecca Perry,

Ephraim Knobbs. Occasionally there occurs a typical Catholic name such as Teresa Bagnall. Thus

Cresswells Catholic congregation, at the beginning of the 19th century, consisted almost entirely of local

Staffordshire folk, the descendants of penal day recusants.

ix

In 1791 it became legal for Catholics to own places of worship and so a small church was built next

to the priests house at Cresswell. In 1816 Fr. Baddeley, who succeeded Fr. Tasker in 1815, set about

building the present church. Lady Mary Stourton, a member of the family who owned the Draycott

estate, provided him with funds; there is a tradition that Fr. Baddeley built the church with his own

hands. According to the Directory for 1851 the chapel was built for a cost of 800, a considerable sum in

1816. Thomas Baddeley also began a small college at the presbytery to prepare young men for the

priesthood (many of the English seminaries abroad had been disorganised and dispersed by the French

Revolution). To assist him, Fr. Baddeley had the Rev. Thomas Laken and the Rev. William Wareing, who

later became bishop of the newly constituted diocese of Northampton. The Rev. Edward Daniel,

afterwards priest at Lane End (Longton) completed his course for the priesthood at Cresswell and was

ordained at Aston Hall. The Rev. Charles Jones was ordained in the new church at Cresswell on April 28th

1820. Bishop Milners remarks, when the proposal to use Cresswell as a seminary was put to him, is worth

recording: he said it pleased him to see Cresswell put to some useful purpose instead of being a mere

cheese-making place. It was well known that Bishop Milner disliked cheese. The seminary ceased to

function when Fr. Baddeley died of consumption in 1823. There is a reliable tradition which attributes his

illness to the rigorous journey he made on the outside of a coach to Yorkshire in order to visit his patron,

Lady Stourton. His epitaph seems to confirm this: Sacred to the memory of Revd. T. Baddeley who

departed this life on the eighteenth (18th) of Feb. 1823 in the 30th year of his age. By the zeal in the

discharge of duty and his indefatigable labours in doing he brought himself to an early grave. His mortal

remains repose near this spot in the hope that his flock, the object of his labours and care, will not forget

to make a grateful return, by their prayers for his departed soul.

x

Throughout the 19th century the Catholic church in England as a whole continued to flourish, but

the great increase in population was in the new manufacturing towns where great numbers of Irish

immigrants came to settle. At the beginning of the 19th century Cresswell and Cobridge were the only

Catholic centres in North Staffordshire; at the end of the century there were Catholic congregations,

churches and schools all over the Potteries and North Staffordshire.

In 1834 the Catholic Magazine already had this to say: the mission of Painsley and Cresswell,

formerly called the Draycott mission, extended over a large district and was the mother church of the

whole of N. Staffs. Within its circuits not fewer that seven chapels have been erected within these years,

to wit, Cobridge (?), Newcastle, Caverswall, Lane End, Alton Towers, Cheadle, Leek.

1

When Canon Dunne celebrated his golden jubilee as a priest at Cresswell in 1878, Bishop

Ullathorne wrote to him: from your quiet retreat you have watched many great and unanticipated

changes, changes that would have astonished men of your earlier years, who have dropped off one by

one like autumn leaves, whilst you have kept your greenness. Cresswell continued to have a relatively

high Catholic population during the 19th century so, when a visitation was made by the bishop in 1889,

it was reported that there were about 200 souls in the parish. Only 13 had not made their Easter duties.

Nevertheless, by 1889 Cresswell had long been superseded in size and importance by other parishes in

the area, but its long and continuous tradition of loyalty to the Catholic faith, stretching back beyond the

reign of Elizabeth I, is an inspiring example of people clinging to a faith they value.

xi

A place with a history as long as the Cresswell mission naturally has material evidence of its past as

well as spiritual. The church itself is the first obvious material witness. It is a rather large building

compared with Catholic churches built at the same period in other parts of rural England. At this time

such buildings were constructed small and unpretentious. Often they were so closely combined with the

presbytery as to be almost indistinguishable from it. This was due to prevailing anti-papal prejudice.

There is a drawing of the church made in 1841 kept in the Salt Library at Stafford. The only apparent

difference between the building as it was and the present one are two gothic type pinnacles on either

side of the front gable, a small belfry near the sacristy door and, of course, no entrance porch: this latter

feature was added recently. We do not have an early picture of the interior, but it must have been quite

simple originally; the rood screen, removed in recent years, was a design and was installed some years

after the church was built. The baptismal font was also designed by Pugin and was used for the first time

when Joseph Wooldridge was baptised on April 5th 1845. The altar is apparently not the original one: it is

said to come from Caverswall. The stained glass window is in memory of Lady Mary Stourton,

benefactress of the church. There are two priests buried in the church: Canon Dunne, who served the

parish for 51 years (1830-1881) is buried in front of the altar, and Fr. Baddeley, who built the church, lies

beneath his epitaph. On the north wall there are two inscriptions: they are memorials to Fr. James Tasker

and Fr. Edward Granhan; both these priests graves are in St. Margarets, Draycott. On the south wall there

is an inscription in memory of two members of the Stourton family.

The church plate has a great sentimental value for Catholics with a sense of history. There is a

small chalice which was secretly made in England during the reign of James I; its precise date is about

1612. We are only able to date it by its style; there is no hallmark or makers mark since it was illegal to

make such popish items. The chalice is an imitation, medieval, gothic - style vessel. According to an oral

tradition it was hidden during the Civil War and came to light again during the 19th century. Another

chalice, dating from the end of the 17th century, is unique in design: simple and not ornate. This may be

one referred to in a letter from the Rev. Edward Coyney dated 1781: the old silver chalice belonging to

Mr. Robert Fitzherbert or the chalice which is at Painsley belonging to ye secular clergy. There is also a

small pyx engraved with the Lamb of God symbol and the crucifixion scene. This is also without

hallmark or makers mark; it is of English workmanship, made between 1625-1649. Some of the most

poignant reminders of the past are the two small slate altar stones, on which are incised five crosses.

These slabs were used in the days of persecution for the celebration of mass since there were no

permanent altars.

The ancient embroidered orphreys taken from pre-Reformation 16th century vestments are

perhaps the most impressive reminders of Cresswells history. A number of ancient parishes in England

have similar examples of medieval needlework, but on the whole they are somewhat rare. So far we have

no historical data telling us how these vestments came to be at Cresswell. The most probable

explanation is that they were bought at the Reformation from some local abbey or church by Sir Philip

Draycott. However, those we know he bought are accurately described in the state archives; their

description does not tally with the Cresswell vestments. Sir Philip refers to the furniture of his chapel at

Painsley. When he made his will in 1558 he mentions vestments, presumably pre-Reformation ones: I

leave to my three daughters aforesaid all my new lynen cloth except so much as will make 3 altar clothez

for my chapel, which I wyll my cozen (John Draycott - really his grandson) and heyre shall have with a

chalys and patent of silver and a pyx of silver (ciborium) which I wold shold be halowyd and he to have

my vestments, mass boke and other things to my chapel belonging. He also left some vestments to his

chapel at Upton near Sibson in Leicestershire.

Another, less likely, explanation is that the Cresswell vestments came from Yorkshire. The evidence

for this is contained in a letter written from York to Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, in 1582: I was informed by

Wortley that they (a Mr. Thompson and companion) let a cloak (a bag) full of vestments at Thomas

Watertons house, whereupon I directed a commission for taking him and his wife. But before the

pursuivant came they fled, and, as is supposed, are now with his brother (in law) ~ Mr Draycott of

Painsley in Staffordshire. This Mr. Waterton and his wife settled, for some time at least, at Blythe Ford

(Bridge?). Were they able to bring their church vestments with them to Painsley? Are they, in fact, the

ones found at Cresswell?

In spite of uncertainty about their provenance, the Cresswell vestment orphreys are genuine 16th

century work. They consist of a series of pictures of Christ, the Blessed Virgin and saints. Among the saints

portrayed are: St. Jerome, St. Francis of Assissi, St. Peter, St. Paul, St. Mary Magdalen, Moses etc. At present

the chasubles on which these medieval orphreys are mounted are used for the great feasts of the year.

During the penal days the Catholics of Draycott parish often buried their dead secretly near St.

Margarets churchyard. When they were permitted to have their own cemetery, the one near St. Marys

started to be used. In the centre Fr. Thomas Scott lies buried. He was at Cresswell between the years

1882-1922. As we have seen, some of his predecessors were interred in Draycott church. In the Draycott

chapel are the tombs of the lords of the manor and their families. The brass plate bearing Anthony

Draycotts epitaph is attached to a pew in the nave: the slab from William Draycotts tomb is fixed to the

wall at the entrance to his familys chapel. In the chapel itself there are the tombs of Sir Richard de

Draycott, who died around 1260: there are the tombs of John Draycott, Richard Draycott and others but,

most impressive of all, is that of Sir Philip Draycott and his wife, with effigies of their five sons and five

daughters. It was he who began the tradition of Roman Catholic recusancy in the parish of Draycott-le-

Moors.

Finally, one of the most important and impressive testimonies to the continuity of Cresswells

Roman Catholic community is the long list of priests who served the mission for almost four

hundred years.

Priests at St Marys Roman Catholic Church Cresswell

Anthony Draycott 1570

Itinerant Priests:

R Jones (?)

T Smith(?) 1570 - 1652

J. Babbington (?)

Robert Fitzherbert 1652 - 1701

Edward Coyney 1701 - 1722

Thomas Mackworth 1722 - 1726

George Leyburne 1727 - 1736

Walter Fleetwood

(?) Foley 1570 - 1652

(?) Turner

Alban Butler 1749 - 1751

George Hardwick 1751 - 1759

Francis Hinde

Edward Ball 1759 - 1765

James Lolli

Edward Granhan 1765 - 1776

James Tasker 1776 - 1815

Thomas Baddeley 1815 - 1823

William Wareing 1823 - 1830

John Dunne 1830 - 1881

S.E. Bathurst 1881 - 1882

Thomas Scott 1882 - 1922

Timothy Purcell 1922 - 1931

Raymond Walshe 1931 - 1949

Gerard Peuleve 1949 - 1961

Patrick Meagher 1961 - 2001

Peter Foley 2001 - 2003

Jan Nowotnik 2003 -

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Lake Parochial History of CornwallDokumen7 halamanThe Lake Parochial History of CornwallnaokiyokoBelum ada peringkat

- March 2013Dokumen10 halamanMarch 2013poeticmediaBelum ada peringkat

- Leicestershire Building Stone AtlasDokumen34 halamanLeicestershire Building Stone AtlasThomas StanyardBelum ada peringkat

- Iraq Vernacular ArchitectureDokumen49 halamanIraq Vernacular ArchitectureOuafae BelrhitBelum ada peringkat

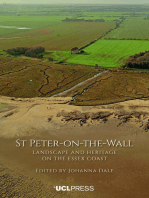

- St Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastDari EverandSt Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastJohanna DaleBelum ada peringkat

- Crossroads in Time Philby and Angleton A Story of TreacheryDari EverandCrossroads in Time Philby and Angleton A Story of TreacheryBelum ada peringkat

- Life Hope Truth Booklet Why Does God Allow Suffering PDFDokumen14 halamanLife Hope Truth Booklet Why Does God Allow Suffering PDFMC NPBelum ada peringkat

- Derbyshire's Strategic Stone StudyDokumen20 halamanDerbyshire's Strategic Stone StudyKatya GibbBelum ada peringkat

- Comments On Frank Miles Visitors Books 1947-48 & 1953-54Dokumen179 halamanComments On Frank Miles Visitors Books 1947-48 & 1953-54Trev BakerBelum ada peringkat

- New Uses For Old Buildings PDFDokumen28 halamanNew Uses For Old Buildings PDFSilvia BotezatuBelum ada peringkat

- 2013-2014 - Helen K. Bond - Historical Jesus (Course)Dokumen7 halaman2013-2014 - Helen K. Bond - Historical Jesus (Course)buster301168100% (1)

- Henry de Percy, 1st Baron Percy of Alnwick (25 March 1273Dokumen7 halamanHenry de Percy, 1st Baron Percy of Alnwick (25 March 1273Alia100% (1)

- 19 Biodet. Stone in Trop.Dokumen96 halaman19 Biodet. Stone in Trop.Francis GuillenBelum ada peringkat

- OengusDokumen10 halamanOengusicdoubleBelum ada peringkat

- Medieval Britain and the Norman ConquestDokumen3 halamanMedieval Britain and the Norman ConquestLeïla PendragonBelum ada peringkat

- Scottish Place-Names Resource GuideDokumen6 halamanScottish Place-Names Resource GuideCarl HewettBelum ada peringkat

- UK Honours List 2016Dokumen124 halamanUK Honours List 2016CrowdfundInsiderBelum ada peringkat

- The Ejected of 1662 in Cumbria and WestmorlandDokumen812 halamanThe Ejected of 1662 in Cumbria and WestmorlandlifeinthemixBelum ada peringkat

- VI. Scarf JointsDokumen8 halamanVI. Scarf JointsCristian Morar-BolbaBelum ada peringkat

- Privy Council 1627 - 1628 V2Dokumen837 halamanPrivy Council 1627 - 1628 V2Geordie WinkleBelum ada peringkat

- Robert MoffatThe Missionary Hero of Kuruman by Deane, David J.Dokumen86 halamanRobert MoffatThe Missionary Hero of Kuruman by Deane, David J.Gutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- Bill Harvey On Arch FailuresDokumen8 halamanBill Harvey On Arch FailuresChuck NorrieBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridgeshire Parish Registers Marriages 1599-1837Dokumen188 halamanCambridgeshire Parish Registers Marriages 1599-1837lifeinthemix100% (2)

- This Is Our Story-Scotland & The Slave TradeDokumen2 halamanThis Is Our Story-Scotland & The Slave TradeinnocentbystanderBelum ada peringkat

- ST Andrews Foundation Legends PDFDokumen41 halamanST Andrews Foundation Legends PDFFrancisMontyBelum ada peringkat

- ISCR2014 ProceedingsDokumen126 halamanISCR2014 ProceedingsGerman Cruz R100% (1)

- SMRT 161 Mijers - 'News From The Republick of Letters' 2012 PDFDokumen233 halamanSMRT 161 Mijers - 'News From The Republick of Letters' 2012 PDFEsotericist Minor100% (1)

- EURO INOX - Colouring Stainless SteelDokumen24 halamanEURO INOX - Colouring Stainless SteelFernando Casanova RicaldoniBelum ada peringkat

- WalesDokumen11 halamanWalesДарья СелинаBelum ada peringkat

- Lostwithiel BrochureDokumen40 halamanLostwithiel BrochureSachaspBelum ada peringkat

- (BS EN 594 - 1996) - Timber Structures. Test Methods. Racking Strength and Stiffness of Timber Frame Wall Panels.Dokumen16 halaman(BS EN 594 - 1996) - Timber Structures. Test Methods. Racking Strength and Stiffness of Timber Frame Wall Panels.Adel100% (1)

- Historic Churches of Dover NJDokumen18 halamanHistoric Churches of Dover NJDarrin ChambersBelum ada peringkat

- Rural Houses of The North of Ireland - Alan GaileyDokumen6 halamanRural Houses of The North of Ireland - Alan Gaileyaljr_2801Belum ada peringkat

- ArchesDokumen11 halamanArchesTinashe MambarizaBelum ada peringkat

- Blackfriars Conservation PlanDokumen86 halamanBlackfriars Conservation PlanWin ScuttBelum ada peringkat

- Lamont Short HistoryDokumen10 halamanLamont Short HistoryMélanie-Vivianne PietteBelum ada peringkat

- (1885) The Tombs, Monuments, Etc., Visible in Saint Paul's Cathedral Previous To Destruction by Fire in A.D. 1666Dokumen208 halaman(1885) The Tombs, Monuments, Etc., Visible in Saint Paul's Cathedral Previous To Destruction by Fire in A.D. 1666Herbert Hillary Booker 2ndBelum ada peringkat

- Yorkshire Marriage Registers. West Riding by Blagg, Thomas Matthews James, Cholmondeley Sherwood Goodall, James William Blumhardt, E. K. (Edward Keane)Dokumen352 halamanYorkshire Marriage Registers. West Riding by Blagg, Thomas Matthews James, Cholmondeley Sherwood Goodall, James William Blumhardt, E. K. (Edward Keane)Victor R Satriani100% (2)

- HiddenAberdeenshire by DR Fiona-Jane Brown ExtractDokumen20 halamanHiddenAberdeenshire by DR Fiona-Jane Brown ExtractBlack & White Publishing0% (1)

- Standard Bracing of 'Room in The Roof' (Attic) Trussed Rafter RoofsDokumen4 halamanStandard Bracing of 'Room in The Roof' (Attic) Trussed Rafter Roofsbigmac2Belum ada peringkat

- Design and Fabrication of Plywood Stressed-Skin PanelsDokumen40 halamanDesign and Fabrication of Plywood Stressed-Skin PanelsPatrice AudetBelum ada peringkat

- Conservation PlanDokumen27 halamanConservation PlanSSBelum ada peringkat

- Directory of Mines and QuarriesDokumen250 halamanDirectory of Mines and QuarriesIndrajeet KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Scotish Declaration Arbroath 1320Dokumen5 halamanScotish Declaration Arbroath 1320Erden SizgekBelum ada peringkat

- Chester Castle Conservation Plan Vol IDokumen129 halamanChester Castle Conservation Plan Vol IWin ScuttBelum ada peringkat

- Norwegian Stave Churches - in Dietrichson and Håkon Christie ResearchDokumen14 halamanNorwegian Stave Churches - in Dietrichson and Håkon Christie ResearchGuilherme GalegoBelum ada peringkat

- The Patrician, Vol. IDokumen418 halamanThe Patrician, Vol. ILuca BarducciBelum ada peringkat

- SHCT 154 Holloway III - Andrew Melville and Humanism in Renaissance Scotland 1545-1622 PDFDokumen387 halamanSHCT 154 Holloway III - Andrew Melville and Humanism in Renaissance Scotland 1545-1622 PDFL'uomo della RinascitáBelum ada peringkat

- Guide Timber in Leaky Buildings DBH June 2012Dokumen24 halamanGuide Timber in Leaky Buildings DBH June 2012Yanina MashkinaBelum ada peringkat

- Completepeerageo 04 CokaDokumen804 halamanCompletepeerageo 04 Cokajamieon100% (1)

- [Sermo_ Studies on Patristic, Medieval, And Reformation Sermons and Preaching, 11] Martha W. Driver, Veronica O'Mara - Preaching the Word in Manuscript and Print in Late Medieval England_ Essays in Honour of Susan PowDokumen414 halaman[Sermo_ Studies on Patristic, Medieval, And Reformation Sermons and Preaching, 11] Martha W. Driver, Veronica O'Mara - Preaching the Word in Manuscript and Print in Late Medieval England_ Essays in Honour of Susan PowcpojrrrBelum ada peringkat

- Siward Digri of Northumberland: A Viking Saga of Danes in EnglandDokumen26 halamanSiward Digri of Northumberland: A Viking Saga of Danes in EnglandcarlazBelum ada peringkat

- Liberton. (Good)Dokumen213 halamanLiberton. (Good)Geordie Winkle100% (1)

- Code of Practice For The Installation of Remedial Wall Ties Lateral Restraint TiesDokumen12 halamanCode of Practice For The Installation of Remedial Wall Ties Lateral Restraint TiesRomeu Branco SimõesBelum ada peringkat

- (Studies in Medieval Reformation Traditions - History, Culture, Religion, Ideas) Pollmann, J., Spicer, A., Judith Pollmann, Andrew Spicer - Public Opinion and Changing Identities I PDFDokumen327 halaman(Studies in Medieval Reformation Traditions - History, Culture, Religion, Ideas) Pollmann, J., Spicer, A., Judith Pollmann, Andrew Spicer - Public Opinion and Changing Identities I PDFalvarado_sofia7Belum ada peringkat

- Boscobel House CMPDokumen99 halamanBoscobel House CMPWin ScuttBelum ada peringkat

- Historic Churches 2018 PDFDokumen56 halamanHistoric Churches 2018 PDFSidra JaveedBelum ada peringkat

- Suspended Ceilings - Requirements and Test Methods: BSI Standards PublicationDokumen10 halamanSuspended Ceilings - Requirements and Test Methods: BSI Standards PublicationHoàng HàBelum ada peringkat

- United Arab Emirates Infrastructure Report Q3 2009Dokumen100 halamanUnited Arab Emirates Infrastructure Report Q3 2009Jon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Portugal BuyingguideDokumen2 halamanPortugal BuyingguideJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Heywoods Lettings PackDokumen15 halamanHeywoods Lettings PackJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- FAA Circular 150 5390 2bDokumen170 halamanFAA Circular 150 5390 2bJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Adel Al Shaffar Kuwait PresentationDokumen76 halamanAdel Al Shaffar Kuwait PresentationJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- 2014 Investor Insights ReportDokumen12 halaman2014 Investor Insights ReportJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- TVR Chimera GuideDokumen5 halamanTVR Chimera GuideJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- D Graz PaperDokumen7 halamanD Graz PaperJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- John Taylor & Sons: Water engineering and sanitationDokumen59 halamanJohn Taylor & Sons: Water engineering and sanitationJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Steel Fab Codes ComparisonDokumen15 halamanSteel Fab Codes ComparisonJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Tutorial EXCELDokumen9 halamanTutorial EXCELroncekeyBelum ada peringkat

- Labour LawDokumen58 halamanLabour LawjanamuraliBelum ada peringkat

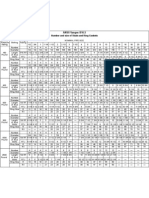

- ANSI Flanges B16.5: Number and Size of Studs and Ring GasketsDokumen1 halamanANSI Flanges B16.5: Number and Size of Studs and Ring GasketsJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- ANSI Flanges B16.5: Number and Size of Studs and Ring GasketsDokumen1 halamanANSI Flanges B16.5: Number and Size of Studs and Ring GasketsJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- FIDIC Rainbow Suite Pt7Dokumen8 halamanFIDIC Rainbow Suite Pt7Jon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- TRC Sec1-Guidelines 1106Dokumen32 halamanTRC Sec1-Guidelines 1106Jon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- World Oil CorrosionDokumen4 halamanWorld Oil CorrosionmutemuBelum ada peringkat

- Roubini Setser US External ImbalancesDokumen65 halamanRoubini Setser US External ImbalancesJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- RICS Damages For Delay To CompletionDokumen20 halamanRICS Damages For Delay To CompletionJon Smith100% (7)

- Aerzen Blowers 054-08 2223Dokumen5 halamanAerzen Blowers 054-08 2223Jon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- 17th Edition DesignDokumen2 halaman17th Edition DesignJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Security of Cloud Computing Providers 2010Dokumen26 halamanSecurity of Cloud Computing Providers 2010mistydewBelum ada peringkat

- JaguarAJ V8EngineDokumen4 halamanJaguarAJ V8EngineJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Heliport DesignDokumen3 halamanHeliport Designrazvanc_roroBelum ada peringkat

- Bio Scrubbers PaperDokumen13 halamanBio Scrubbers PaperJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- WaterTransmissionCode Revision030 (June2007)Dokumen70 halamanWaterTransmissionCode Revision030 (June2007)Jon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Addc Guidlines For LV Services Cable Selection and Fuse RatingDokumen10 halamanAddc Guidlines For LV Services Cable Selection and Fuse RatingJon Smith50% (4)

- Reliant SE5a HandbookDokumen76 halamanReliant SE5a HandbookJon SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Porsche Service SheetDokumen28 halamanPorsche Service SheetJon Smith100% (1)

- Christ The King Final LiturgyDokumen18 halamanChrist The King Final Liturgyken_cejoBelum ada peringkat

- The Nativity of The Lord and Mary, Mother of GodDokumen77 halamanThe Nativity of The Lord and Mary, Mother of GodAries BelandoBelum ada peringkat

- Altar - WPS OfficeDokumen5 halamanAltar - WPS OfficeBrent DawnBelum ada peringkat

- History of Cresswell's Roman Catholic CommunityDokumen9 halamanHistory of Cresswell's Roman Catholic CommunityJon Smith100% (1)

- SaintHenrysChurchAltarServerManual 111414 PDFDokumen17 halamanSaintHenrysChurchAltarServerManual 111414 PDFIsaac Nicholas NotorioBelum ada peringkat

- Egeria 3. Chalice, Donation of King Charles VI of France, 1411 (2008) .Dokumen5 halamanEgeria 3. Chalice, Donation of King Charles VI of France, 1411 (2008) .Kalomirakis DimitrisBelum ada peringkat

- The Black Books of Satan 1,2,3Dokumen77 halamanThe Black Books of Satan 1,2,3gh0st252Belum ada peringkat

- Sacred Vessels and VestmentsDokumen6 halamanSacred Vessels and VestmentsNiklasSch100% (1)

- Mrs Midas IDokumen25 halamanMrs Midas IMenon HariBelum ada peringkat

- Rite of Ordination To The PriesthoodDokumen40 halamanRite of Ordination To The PriesthoodJose RizalBelum ada peringkat

- Thanksgiving Mass High SchoolDokumen41 halamanThanksgiving Mass High SchoolJohnny AbadBelum ada peringkat

- Mrs Midas' LamentDokumen35 halamanMrs Midas' LamentTetiana IvchykBelum ada peringkat

- Pilgrim WaysDokumen173 halamanPilgrim WaysDavid Alton100% (1)

- 03 Preparation of The Gifts - SatmiDokumen12 halaman03 Preparation of The Gifts - SatmiHil Idulsa100% (1)

- Miss AletteDokumen4 halamanMiss AletteRhyx Houell AmboteBelum ada peringkat

- Altar Server ManualDokumen86 halamanAltar Server Manualbabiboiban100% (2)

- Eucharistic Celebration - 93rd Alumni HomecomingDokumen36 halamanEucharistic Celebration - 93rd Alumni HomecomingMark Anthony Muya100% (1)

- EUCHARISTIC PRAYERS TAGALOG AND ENGLISHDokumen22 halamanEUCHARISTIC PRAYERS TAGALOG AND ENGLISHRensutsukiBelum ada peringkat

- FBS 7-DLLDokumen7 halamanFBS 7-DLLJeeNha BonjoureBelum ada peringkat

- Laurence Gardner - Bloodline of The Holy Grail - The Hidden Lineage of Jesus RevealedDokumen15 halamanLaurence Gardner - Bloodline of The Holy Grail - The Hidden Lineage of Jesus RevealedNeelima Joshi90% (10)

- The Bloodline, Starfire & The AnnunakiDokumen30 halamanThe Bloodline, Starfire & The AnnunakiRicardo Piña Harari100% (3)

- Dedicated to God: The Church as Temple and Dwelling Place of GodDokumen37 halamanDedicated to God: The Church as Temple and Dwelling Place of GodIsmael S. Delos ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- Mrs. Midas' Modern TwistDokumen4 halamanMrs. Midas' Modern TwistN FBelum ada peringkat

- Ark Tabernacle Throne Chalice Stand in Coptic Church Revisited DRDokumen10 halamanArk Tabernacle Throne Chalice Stand in Coptic Church Revisited DRKaleab DesalegnBelum ada peringkat

- The Sacrament of The Holy OrdersDokumen11 halamanThe Sacrament of The Holy OrdersAlBelum ada peringkat

- Wicca - Planning and Designing RitualDokumen22 halamanWicca - Planning and Designing RitualAndrés JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- Inaestimabile DonumDokumen7 halamanInaestimabile DonumFrancis LoboBelum ada peringkat

- Sambuhay (Papal Mass On Jan 18 2015)Dokumen8 halamanSambuhay (Papal Mass On Jan 18 2015)Anonymous sqnW6KKBelum ada peringkat

- Blessing of Chalice For PrintingDokumen7 halamanBlessing of Chalice For PrintingIan Joseph ResuelloBelum ada peringkat

- October 9, 2019 Community MassDokumen14 halamanOctober 9, 2019 Community Masspaul_fuentes_4Belum ada peringkat

![[Sermo_ Studies on Patristic, Medieval, And Reformation Sermons and Preaching, 11] Martha W. Driver, Veronica O'Mara - Preaching the Word in Manuscript and Print in Late Medieval England_ Essays in Honour of Susan Pow](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/679569039/149x198/bcab86c91b/1698085967?v=1)