Table 3

Diunggah oleh

Lourdes Espera0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

182 tayangan86 halamanPhonological Processes typically gone by these ages (in years ; months) pre-vocalic voicing car = gar a voiceless sound preceding a vowel is replaced by a voiced consonant. Final consonant deletion comb = coe 3;3 fronting car = tar ship = sip 3;6 consonant harmony cup = pup the pronunciation of a word is influenced by one of the sounds it'should' contain.

Deskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniPhonological Processes typically gone by these ages (in years ; months) pre-vocalic voicing car = gar a voiceless sound preceding a vowel is replaced by a voiced consonant. Final consonant deletion comb = coe 3;3 fronting car = tar ship = sip 3;6 consonant harmony cup = pup the pronunciation of a word is influenced by one of the sounds it'should' contain.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

182 tayangan86 halamanTable 3

Diunggah oleh

Lourdes EsperaPhonological Processes typically gone by these ages (in years ; months) pre-vocalic voicing car = gar a voiceless sound preceding a vowel is replaced by a voiced consonant. Final consonant deletion comb = coe 3;3 fronting car = tar ship = sip 3;6 consonant harmony cup = pup the pronunciation of a word is influenced by one of the sounds it'should' contain.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 86

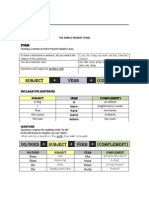

Table 3

Elimination of Phonological Processes in Typical Development

Phonological processes are typically gone by these ages (in years ; months)

PHONOLOGICAL PROCESS EXAMPLE GONE BY APPROXIMATELY

Pre-vocalic voicing pig = big 3;0

Word-final de-voicing pig = pick 3;0

Final consonant deletion comb = coe 3;3

Fronting

car = tar

ship = sip

3;6

Consonant harmony

mine = mime

kittycat = tittytat

3;9

Weak syllable deletion

elephant = efant

potato = tato

television =tevision

banana = nana

4;0

Cluster reduction

spoon = poon

train = chain

clean = keen

4;0

Gliding of liquids

run = one

leg = weg

leg = yeg

5;0

Stopping /f/ fish = tish 3;0

Stopping /s/ soap = dope 3;0

Stopping /v/ very = berry 3;6

Stopping /z/ zoo = doo 3;6

Stopping 'sh' shop = dop 4;6

Stopping 'j' jump = dump 4;6

Stopping 'ch' chair = tare 4;6

Stopping voiceless 'th' thing = ting 5;0

Stopping voiced 'th' them = dem 5;0

Table 2

Phonological Processes in Typical Speech Development

Phonological

Process

Example

Description

Pre-vocalic voicing car = gar

A voiceless sound preceding a vowel is replaced

by a voiced sound.

Word final devoicing red = ret

A final voiced consonant is replaced by a

voiceless consonant

Final consonant

deletion

boat = bo

A final consonant is omitted (deleted) from a

word.

Velar fronting car = tar A back sound is replaced by a front sound.

Palatal fronting ship = sip sh or zh are replaced b y s or z respectively

Consonant harmony cup = pup The pronunciation of a word is influenced by one

of the sounds it 'should' contain.

Weak syllable deletion

telephone =

teffone

Weak (unstressed) syllables are deleted from

words of more than one syllable.

Cluster reduction try = ty A cluster element is deleted or replaced.

Gliding of liquids ladder = wadder Liquids are replaced by glides.

Stopping ship = tip A stop consonant replaces a fricative or affricate.

Natural Phonology

I. Introduction

This theory is to be distinguished from the approach known as natural generative phonology (see Natural Generative

Phonology). The speech of very young children is clearly different in certain respects from that of adults speaking the

same language. Natural phonology assumes that childrens speech is governed by a large number of natural phonetic

constraints (see sect. 1), whereas adults have learned to suspend many of these constraints (Sects.2) and there by enjoy

the benefits of a more complex phonological system. In each language, mature speakers have learned to suspend

certain constraints, but leave others unaffected (Sect. 5). The set of unaffected constraints varies from one language to

another; this often has striking effects when a word is borrowed from one language into another (see Sect.6; see also

Loanwords: Phonological Treatment).

II. Processes

Natural phonologists have used the term process to refer to a natural phonetic constraint, i.e., a constraint which simplifies

articulation. Processes are typical of young childrens speech. The following are examples of processes:

(a) Consonant clusters are reduced to single segments (fly [flai] becomes[fai]).

(b) Unstressed syllables are deleted (potato [p teitou] becomes [teitu]).

(c) Voiced stops (e.g., [b], [d]) are made voiceless ([p], [t]) since the airflow required by voicing is interrupted by the fact of

complete closure of the oral tract.

(d) Consonants produced with the tongue body (e.g., [k], [g]) become articulated with the tongue blade ([t], [d] respectively).

Frontness of backness, and lip rounding or spreading, permeate all the segments of a word. The writers son had at one stage

of his development [dadi] Daddy, with frontness ([a].. cardinal vowel no.

4) and nonrounding spreading from the imtial [d] [momu] Mummy, with labiality of initial [m] spreading as rounding and

concomitant backness to the remainder of the word, and [g gw] doggie, with backness and nonlabiality of initial [g] spreading

throughout.

Some of these processes may have the effect of giving rise to sounds which are not to be found in the adult language. The

back unrounded vowel [w] of [g fw] (see (e) above) is a case in point; again, at one stage the same child produced scarf with

the final fricative assimilated to the initial velar plosive; [gax]-the velar fricative [x] did not appear in his parents speech.

Three types of process have been distinguished:

(a) Prosodic: mapping words, phrases and sentences on to basic rhythm and intonaation paatterns.

(b) Fortition: strengthening a sound (e.g. devoicing of obstruents), intensifying the contrast of a sound with a neighboring

sound (dissimilation), adjusting the

timing of movements so as to have the effect of inserting a new sound (sense[sens][sents]) or of making a nonsyllabic

consonant syllabic (prayed [preid] [preid]).

(c) Lenition: weakening a sound (e.g., making a stop into a fricative between vowels), decreasing the contrast of a sound

with a neighboring sound (assimilation, harmony), adjusting the timing of movements so as to have the effect of deleting

a sound (cents [scnts][sens]) or of making a syllabic consonant nonsyllabic (parade [preid][preid]).

It is claimed that fortitions are aimed at increasing intelligibility for the hearer, but that they often have the concomitant effect of

easing pronounccability; lenitions, on the other hand, have this latter effect as their exclusive goal. The effect of fortitions becomes

salient in slower, more formal speech styles, while lenitions are more likely to operate in faster, more colloquial styles.

III. Processes and Rules

Some processes may govern phonological alternations. For example, in German the cool meaning dog is pronounced [hund]

when followed by a suffix beginning with a vowel; Hunde dogs is [hund] followed by plural suffix [a]; in the nominative singular,

however, where there is no suffix, one has Hund [hunt]; this [d]-[t] alternation is brought about by the devoicing process ( c) above

(Sect. 1), which remains operative word-finally in German.

However, not all alternations arise from the operation of processes. Thus, in English, when electric takes the suffixity, its final /k/

becomes /s/ (velar softening) when serene lakes the sulfixity the long [I:] becomes short [e](trisyltabic laxing). The principles

governing these alternations are called rules in the theory. Rules typically operate in selective fashion (not all /k/ phonemes become

/s/ when followed by written i or e-kit, keep), are sensitive to grammatical considerations, and may tolerate exceptions (obese retains

long [I;] in obesity, even though trisyllabic laxing would be expected to occur). Processes, on the other hand operate across the

board with no exceptions. Rules need to be learnt, processes are (at least partially) unlearnt.

Intervocalic alveolar flapping

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Flapping" redirects here. For other uses, see Flap (disambiguation).

This article contains IPA phonetic symbols.

Without proper rendering support, you may see

question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead

of Unicode characters.

Intervocalic alveolar flapping is a phonological process found in many dialects of English, especially North American English (to

varying extents) and Australian English, by which either or both prevocalic (preceding a vowel) /t/ and /d/ surface as the alveolar flap

[] after sonorants other than //, /m/, and (in some environments) /l/.

after vowel: butter

after r: barter

after l: faculty

[citation needed]

(but not immediately post-tonic: alter [t], not [*])

The term "flap" is often used as a synonym for the term "tap", but the two can be distinguished phonetically. A flap involves a rapid

movement of the tongue tip from a retracted vertical position to a (more or less) horizontal position, during which the tongue tip

brushes the alveolar ridge. A tap involves a rapid upward and downward movement of the tongue tip, the upward movement being

voluntary and the lowering involuntary. The sound referred to here is the alveolar tap, not the flap, and hence "tapping" is the correct

term from a phonetic point of view (see also flap consonant). However, no languages are known to contrast taps and flaps (both are

represented in the IPA as ), and the term "flapping" is ingrained in much of the phonological literature,

[1]

so it is retained here.

Flapping/tapping is a specific type of lenition, specifically intervocalic weakening. For people with the merger these following

utterances sound the same or almost the same:

[show]Homophonous pairs

For most (but not all) speakers the merger does not occur when an intervocalic /t/ or /d/ is followed by a syllabic n, so written and

ridden remain distinct. A non-negligible number of speakers (including pockets in the Boston area) lack the rule that glottalizes t and d

before syllabic n, and therefore flap/tap /t/ and /d/ in this environment. Pairs like potent : impotent, with the former having a

preglottalized unreleased t or a glottal stop (but not a flap/tap) and the latter having either an aspirated t or a flap/tap, suggest that the

level of stress on the preceding vowel may play a role in the applicability of glottalization and flapping/tapping before syllabic n.

Some speakers in the Pacific Northwest turn /t/ into a flap but not /d/, so writer and rider remain distinct even though the long i is

pronounced the same in both words.

[citation needed]

Flapping/tapping does not occur in most dialects when the /t/ or /d/ immediately precedes a stressed vowel, as in attack [tk], but

can flap/tap in this environment when it spans a word boundary, as in got over [ov], and when a word boundary is embedded

within a word, as in buttinsky [bnski]. Australian English also flaps/taps word-internally before a stressed vowel in words like

fourteen.

In accents characterized by Canadian raising, such words as riding and writing, both of which have an alveolar flap, continue to be

distinguished by the preceding vowel: though the consonant distinction is neutralized, the underlying voice distinction continues to

select the allophone of the /a/ phoneme preceding it. Thus for many North Americans, riding is [a] while writing is

[].

[citation needed]

Vowel duration may also be different, with a longer vowel before tap realizations of /d/ than before tap

realizations of /t/. At the phonetic level, the contrast between /t/ and /d/ may be maintained by these non-local cues, though as the cues

are quite subtle, they may not be acquired/perceived by others. A merger of /t, d/ can then be said to have occurred in this

context.

[citation needed]

The cluster [nt] can also be flapped/tapped; the IPA symbol for a nasal tap is []. As a result, in quick speech, words like winner and

winter can become homophonous. Flapping/tapping does not occur for most speakers in words like carpenter and ninety, which

instead surface with [d].

[2]

A similar process also occurs in other languages, such as Western Apache (and other Southern Athabaskan languages). In Western

Apache, intervocalic /t/ similarly is realized as [] in intervocalic position. This process occurs even over word boundaries. However,

tapping is blocked when /t/ is the initial consonant of a stem (in other words tapping occurs only when /t/ is stem-internal or in a

prefix). Unlike English, tapping is not affected by suprasegmentals (in other words stress or tone).

Lenition in Irish English

Lenition in Irish English

The lenition cline

References

The term lenition refers to phonetic weakening, that is an increase in sonority with a given segment. In terms of the following

hierarchy, lenition leads to a movement upwards on the scale. If there is no vertical movement, then at least there is a

movement in point of articulation, above all from the oral to the glottal area.

Lenition normally consists of several steps and diachronically a language may exhibit a shift from stop to zero via a number of

intermediary stages. Attested cases of lenition are represented by the Germanic sound shift (stop to fricative), West Romance

consonantal developments (Martinet 1952) such as lenition in Spanish or more dialectal phenomena such as the gorgia toscana

in Tuscan Italian (Rohlfs 1949; Ternes 1977) or lenition in Canary Spanish (Oftedal 1986).

If one looks at English in this light one can recognise that the alveolar point of articulation represents a favoured site for

phonetic lenition (Hickey 1996, 2009). Alveolars in English can involve different types of alternation (Kallen 2005), three of

which are summarised below, the labels on the left indicating sets of varieties in which these realisations are frequently found.

Variety or group Lenited form of stop Example

American English Tap water [w:]

Urban British English Glottal stop water [w:]

Southern Irish English Fricative water [w:]

Lenition in Irish English

1) Glottalisation of /t/ Glottalisation involves the removal of the oral gesture from a segment. The realisation of /t/ as a glottal

stop [] is a long recognised feature of popular London speech but it is also found widely in other parts of Britain (including

Scotland) as a realisation of intervocalic and/or word-final /t/. This does not hold for supraregional varieties of Irish English,

especially in the south. The south has a fricative [] in these positions while the north frequently has a flap, cf. butter [b]

versus [b]. As a manifestation of lenition, glottalisation occurs in vernacular Dublin English, e.g. butter [b], right [r].

This fact may explain its absence in non-vernacular Dublin English, despite the change in this variety in recent years.

Glottalisation does not occur in southern rural forms of English either. Nor is it found in Irish so that transfer from the

substrate, either historically or in the remaining Irish-speaking areas, does not represent a source.

The Whole Floor is Wet with glottalisation of final /-t/ [-] (local Dublin speaker)

2) Tapping of /t/ Tapping can also be classified as lenition as it is a reduction in the duration of a segment. Tapping can only

occur with alveolars (labials and velars are excluded). Furthermore, it is only found in word-internal position and only in

immediately post-stress environments. As tapping is phonetically an uncontrolled articulation, it cannot occur word-finally

(except in sandhi situations, e.g. at^all) and cannot initiate a stressed syllable. For some younger non-local speakers in

Ireland, it is fashionable to use tapping as an alternative to frication, e.g. better ['be] (Hickey 2005: 77f.).

WATER with intervocalic flap (non-local Dublin speaker)

3) Frication of /t/ Of the three main options for the lenition of /t/ across varieties of English, frication is the most

straightforward in terms of increasing sonority. The alveolar stop shifts to an alveolar fricative with no change in place of

articulation or secondary articulation. The details of this shift will be considered below but before this it is necessary to

understand the context in which this shift takes place, i.e. the set of coronal segments in Irish English.

BIT BET BAT BUT (non-local Dublin speaker)

4) /t/ to [h] Especially in word-internal position local speakers can show the realisation of /t/ as [h], rather than using a glottal

stop. The use of these two sounds would appear to be in free variation, at least there is no sociolinguistic distinction between

these sounds though there is, of course, between both of them and the apico-fricative [] which is typical of non-vernacular

speech throughout Ireland.

LETTER with medial [h] (local Dublin speaker)

5) T-to-R An occasional feature of local Dublin English whereby and intervocalic /t/ can be shifted to [r] as part of lenition.

Normally, local speakers have T-glottalisation, T-tapping or T-deletion intervocalically. However, after a stressed vowel and

before a further closed syllable [r] can be found as in get up! [grp].

The lenition cline

T-lenition is a universal feature of southern Irish English. The fricative t [] occurs (i) intervocalically, as in city [si], and (ii)

word-finally and before a pause as in sit [s]. This apico-alveolar fricative can be further weakened along a cline which, in local

Dublin English, can lead to the deletion of /t/ entirely.

The following tables offer more detailed information about (i) syllable position and lenition in Irish English and (ii) the lenition

alternatives which exist.

A general term in phonetics for the process by which a speech sound becomes similar or identical to a neighboring sound. In the opposite

process, dissimilation, sounds become less similar to one another.

Assimilation is the influence of a sound on a neighboring sound so that the two become similar or the same. For example, the Latin

prefix in- 'not, non-, un-' appears in English as il-, im-. and ir- in the words illegal, immoral, impossible (both m and p are bilabial

consonants), and irresponsible as well as the unassimilated original form in- in indecent and incompetent. Although the assimilation of

the n of in- to the following consonant in the preceding examples was inherited from Latin, English examples that would be

considered native are also plentiful. In rapid speech native speakers of English tend to pronounce ten bucks as though it were written

tembucks, and in anticipation of the voiceless s in son the final consonant of his in his son is not as fully voiced as the s in his

daughter, where it clearly is [z]."

(Zdenek Salzmann, Language, Culture, and Society: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Westview, 2004)

"Features of adjacent sounds may combine so that one of the sounds may not be pronounced. The nasal feature of the mn

combination in hymn results in the loss of /n/ in this word (progressive assimilation), but not in hymnal. Likewise, the alveolar (upper

gum ridge) production of nt in a word such as winter may result in the loss of /t/ to produce a word that sounds like winner. However,

the /t/ is pronounced in wintry."

(Harold T. Edwards, Applied Phonetics: The Sounds of American English. Cengage Learning, 2003)

Partial Assimilation and Total Assimilation

"[Assimilation] may be partial or total. In the phrase ten bikes, for example, the normal form in colloquial speech would be /tem

baiks/, not /ten baiks/, which would sound somewhat 'careful.' In this case, the assimilation has been partial: the /n/ sound has fallen

under the influence of the following /b/, and has adopted its bilabiality, becoming /m/. It has not, however, adopted its plosiveness.

The phrase /teb baiks/ would be likely only if one had a severe cold! The assimilation is total in ten mice /tem mais/, where the /n/

sound is now identical with the /m/ which influenced it."

(David Crystal, Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 6th ed. Blackwell, 2008)

Ads

New Muslims eLearning

newmuslims.com

Learn for free your new faith in an easy and systematic way.

Lat

gosur.com/Latitude-Map

Interactive Map. Lat

Alveolar Nasal Assimilation: "I ain't no ham samwich"

"Many adults, especially in casual speech, and most children assimilate the place of articulation of the nasal to the following labial

consonant in the word sandwich:

sandwich /snw/ /smw/

The alveolar nasal /n/ assimilates to the bilabial /w/ by changing the alveolar to a bilabial /m/. (The /d/ of the spelling is not present for

most speakers, though it can occur in careful pronunciation.)"

(Kristin Denham and Anne Lobeck, Linguistics for Everyone. Wadsworth, 2010)

Direction of Influence

"Features of an articulation may lead into (i.e. anticipate) those of a following segment, e.g. English white pepper /wat 'pep/

/wap 'pep/. We term this leading assimilation.

"Articulation features may be held over from a preceding segment, so that the articulators lag in their movements, e.g. English on the

house /n 'has/ /n n 'has/. This we term lagging assimilation.

"In many cases there is a two-way exchange of articulation features, e.g. English raise your glass /'rez j: 'gl:s/ /'re : 'gl:s/.

This is termed reciprocal assimilation."

(Beverley Collins and Inger M. Mees, Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students, 3rd ed. Routledge, 2013)

Elision and Assimilation

"In some situations, elision and assimilation can apply at the same time. For example, the word 'handbag' might be produced in full as

/hndbg/. However, the /d/ is in a site where elision is possible, so the phrase could be produced as /hnbg/. Furthermore, when

the /d/ is elided, it leaves /n/ in a position for place assimilation. So, we frequently hear /hmbg/. In this final example, we see again

that connected speech processes have the potential to influence meaning. Is /hmbg/ a rendition of 'handbag' with elision and

dealveolarisation, or is it simply 'ham bag'? In real life, the context and knowledge of the speaker's habitual patterns and preferences

would help you to decide, and you would probably opt for the most likely meaning. So, in reality, we are rarely confused by CSPs

[connected speech processes], although they do have the potential to cause misunderstandings."

(Rachael-Anne Knight, Phonetics: A Coursebook. Cambridge University Press, 2012)

Assimilation:

There are various types of assimilation, all of which have in common that one sound (the target) copies a feature or features of a sound

in its environment (the source). Assimilation may be classified in a number of ways.

A. By direction

1. Anticipatory (Regressive): The source of the assimilation is the second sound in the sequence. An example from English: n m in the

phrase ten billion tem bljn. Here it is the bilabial place of articulation which has been copied from the following b.

2. Perseverative (Progressive): The source of the assimilation is the first sound in the sequence. An example from English: n m in the

word happen hpm. Here it is the bilabial place of the preceding p which has been copied. Also called carry-over assimilation.

3. Coalescent (bidirectional): two segments combine to give a single output segment. Example from English: dd ju ddu.

B. By distance

1. Contact: the source and target are adjacent, though not necessarily in the same syllable or word. Examples as in A1. and A2. above

2. Distant: the source and target are separated by other segments. This is most common with vowel sounds and is called vowel harmony or

umlaut. Distant assimilation of consonant features does occur in child speech where it is usually called consonant harmony.

C. By feature(s) copied

1. Place: The place of articulation of a sound is altered to agree with some sound in its environment. In English, for example, alveolar

consonants are particularly susceptible targets for this kind of assimilation. An example is good girl gg gl, where the plosive at the end

of the first word copies the velar place of the following consonant.

2. Voice: Examples can be found where voiced consonants become voiceless, or voiceless consonants become voiced, under the influence

of a neighbouring segment. An example of the former change often occurs in the English phrase has to hs tu. An example of the latter

change can be seen in French: as (ace) as, as de pique (ace of spades) az d pik.

3. Manner: The manner of articulation of a sound is altered to agree with the manner of a sound in the environment. An example of this

from English is the occasional copying of nasal manner, as in the phrase good night gn nat.

D. By extent

1. Partial: only some phonetic features are copied from source to target.

2. Complete: the target is changed to become identical with the source. An example of this is the definite article l in Arabic. The final

consonant changes to become identical with the initial consonant of a following noun, if this consonant is apical. Example: d dar the

house.

Assimilation and coarticulation are very similar phenomena. The distinction between them is largely one which rests on the analysts

theoretical outlook. In traditional phonemic phonology, assimilation results in a phoneme different from the target, whereas

coarticulation does not. Also the term assimilation is usually reserved for those changes which are completely optional. Coarticulation

on the other hand is usually deemed to be more or less automatic and obligatory.

An obstruent is a consonant sound such as [k], [d], or [f] that is formed by obstructing airflow, causing a strong gradient of air

pressure in the vocal tract. Obstruents contrast with sonorants, which have no such obstruction.

Obstruents are subdivided into stops, such as [ p, t, k, b, d, ], with complete occlusion of the vocal tract, often followed by a release

burst; fricatives, such as [f, s, , x, v, z, , ], with limited closure, not stopping airflow but making it turbulent; and affricates, which

begin with complete occlusion but then release into a fricative-like release. Obstruents are prototypically voiceless, though voiced

obstruents are common. This contrasts with sonorants, which are prototypically voiced and only rarely voiceless.

n phonetics and phonology, a sonorant is a speech sound that is produced with continuous, non-turbulent airflow in the vocal tract;

these are the manners of articulation that are most often voiced in the world's languages. Vowels are sonorants, as are consonants like

/m/ and /l/: approximants, nasals, taps, and trills. In the sonority hierarchy, all sounds higher than fricatives are sonorants. They can

therefore form the nucleus of a syllable in languages that place that distinction at that level of sonority; see Syllable for details.

The word resonant is sometimes used for these non-turbulent sounds. In this case, the word sonorant may be restricted to non-vocoid

resonants; that is, all of the above except vowels and semivowels. However, this usage is becoming dated.

Sonorants contrast with obstruents, which do stop or cause turbulence in the airflow. They include fricatives and stops (for example,

/s/ and /t/). Among consonants pronounced in the back in the mouth or in the throat (uvulars, pharyngeals, and glottals), the distinction

between an approximant and a voiced fricative is so blurred that no language is known to contrast them.

A typical sonorant inventory found in many languages comprises the following: two nasals /m/, /n/, two semivowels /w/, /j/, and two

liquids /l/, /r/.

[citation needed]

English has the following sonorant consonantal phonemes: /l/, /m/, /n/, //, //, /w/, /j/.

[1]

Table of consonant manners

Obstruents Stops p b t d k g ?

Fricatives f v th s z zh

Affricates t dzh

Sonorants Nasals m n ng

Liquids r l

Glides j w

Obstruent voicing and devoicing

The phenomenon to be considered in this paper is the voicing alternation that obstruents

display in different phonological environments. Example (1) illustrates that voiced

obstruents may alternate with voiceless ones in

English, German, Dutch, and Polish. In the

words below, orthographic representations are given except for the relevant obstruents,

which are given in phonetic transcription within square brackets. Polish data are from

Gussmann (1992).

(1)

a.

English:

scri

[b]e

scri[pt]ure

b.

German:

bewei[z]en

to prove

Bewei[s]

proof

c.

Dutch:

bewij[z]en

to prove

bewij[s]

proof

d.

Polish:

wa[d]a

fault

wa[t]

fault

-

gen.pl.

Example (1a) illustrates that word

-

final obstruents may be voiced i

n English and that that

they can alternate with voiceless obstruents in some morphological contexts (i.e. when

immediately followed by a voiceless obstruent within the same word). Examples (1b

-

d)

show that in German, Dutch, and Polish, word

-

final obstruent

s are invariably voiceless. In

some morphological environments, adjacent obstruents in English must agree in voicing

(1a,

2a), but not in compounds (see 2b). In German, adjacent obstruents need not agree in

voicing (2c). Dutch and Polish are similar to Ger

man in that word

-

final obstruents are

voiceless in these languages (see 1b,c,d), but they differ from German in that obstruent

clusters always agree in voicing (see 2d,e).

(2)

a.

English:

lose [lu:z]

lo[st]

b.

hou[s]e, dog

hou[s.d

]

og

c.

German:

bewei[z]en

to prove

bewei[s.b]ar

1

provable

d.

Dutch:

bewij[z]en

to prove

bewij[z.b]aar

provable

e.

Polish:

z

a[b]a

frog

z

a[pk]a

frog

-

dim.

The next subsection considers a traditional rule

-

based account for the lack of

syllable

-

final

devoicing and the occurrence of voicing assimilation in certain contexts in English.

Subsequently, we discuss syllable

-

final devoicing and the absence of voicing assimilation in

German and, finally, we consider Dutch, which exhibits both wo

rd

-

final devoicing and

voicing assimilation.

1

Here and in subsequent

examples, syllable boundaries are indicated by a dot.

SFB 282 w

orking

paper n

o. 116, 2000, 'Two papers on constraint domains

.

'

HHU Dsseldorf

3

2.1

English voicing assimilation

The morpheme that expresses plural in English is realised as the voiced fricative [z] after

a

vowel (3a), a sonorant consonant (3b), or a voiced obstruent (3c). After a voice

less

obstruent, it is voiceless (3d). This process is known as progressive voicing

assimilation.

(3)

a.

bee

+ /z/

bee[z]

b.

lion

+ /z/

lion[z]

c.

dog

+ /z/

dog[z]

d.

cat

+ /z/

cat[s]

A morpheme that ends in a voiced obstruent in isolation is realised with a voiceless

obstruent before a suffix that consists of

-

or begins wi

th

-

a voiceless obstruent and this

process is called regressive voicing assimilation:

(4)

a.

fi/v/

+ /

T

/

fi[f

T

]

fifth

b.

wi/d/

+ /

T

/

wi[t

T

]

width

In traditional generative phonology, phonological processes are captured by rules of the

form A

B / C

---

D, i.e. an element A changes to

B in between the elements C

and D. To describe the devoicing process in (3d), one may suggest a so

-

called rewrite

rule that assigns the feature [

-

voice] to an obstruent which is immediately preceded by a

voiceless obstruent (5a). Similarly, the ph

onological rule for the devoicing process in (4a,b)

assigns the feature [

-

voice] to an obstruent which is immediately followed by a voiceless

obstruent (5b).

(5)

a.

progressive assimilation:

[

-

son]

[

-

voice] / [

-

son

,

-

voice]

---

b.

regressive assimilation:

[

-

son]

[

-

voice] /

---

[

-

son,

-

voice]

These two rules miss important generalisations. First, the rules suggested above miss the

generalisation that adjacent obstruents mu

st agree in voicing. Second, we need two rules

that both assign the same feature value, viz. [

-

voice] and we thus miss the generalisation that

obstruents tend to be voiceless. These generalisations or conspiracies can be expressed

as constraints against

marked structure. Constraint (6a) says that neighbouring obstruents

must have the same specification for the feature [voice] (see e.g. Lombardi 1996, 1999)

and constraint (6b) says that obstruents may not be specified for [+voice].

(6)

a.

AGREE:

C

C

b.

* C

[

-

sonorant]

\

/

|

[

voice]

[+voice]

SFB 282 w

orking

paper n

o. 116, 2000, 'Two papers on constraint domains

.

'

HHU Dsseldorf

4

In what follows, I show that the rules formulated in (5a) and (5b) are language specific,

whereas the constraints in (6a) and (6b) e

xpress universal tendencies. Furthermore, I show

that these generalisations also emerge as the unmarked case in child language and in

second

language acquisition.

The constraints in (6a) and (6b) are not absolute in the sense that they have to be

satisfie

d in all surface representations. Rather, the assumption in OT is that constraints

express tendencies and languages may choose to assign more weight to some constraints

and less weight to others. In English combinations of an obstruent final root and an

ob

struent initial affix, constraints (6a) and (6b) are satisfied and both obstruents are

voiceless in the surface form (see 4a,b). In English compounds, adjacent obstruents may

differ in their voicing specification in violation of (6a). Similarly, syllable

-

f

inal obstruents are

voiceless in German, even when a voiced obstruent follows, so that constraint (6a) is

violated in those cases as well.

2.2

German syllable

-

final devoicing

In German, obstruents which are voiced word

-

internally are realised as voicele

ss

obstruents in word

-

final position (see Wiese 1996 and references cited there):

(7)

a.

Hunde

-

Hun[t]

dogs

dog

b.

Diebe

-

Die[p]

thieves

thief

c.

Berge

-

Ber[k]

mountains

mountain

d.

Mu[z]e

-

Mau[s]

mice

mou

se

Furthermore, all syllable

-

final obstruents are voiceless, irrespective of the voicing

specification of the neighbouring segment.

(8)

a.

Freun[d]e

-

freun[t.l]ich

friends

friendly

b.

Lie[b]e

-

Lie[p.l]ing

love

beloved, darling

c.

bie

[g]en

-

bie[k.z]am

to bend

flexible

d.

bewei[z]en

-

bewei[s.b]ar

to prove

provable

We may formulate devoicing of syllable

-

final obstruents as a phonological rule that assigns the

feature [

-

voice] to an obstruent in syllable final position (

9). Alternatively, one may suggest a

so

-

called delinking rule which deletes the feature [+voice] from an underlying

representation

(cf. Lombadi 1995), or one may formulate a constraint which says that syllable

-

final

obstruents are not voiced (10).

(9)

Final devoicing:

[

-

son]

[

-

voice] /

Consonant voicing and devoicing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sound change and alternation

Metathesis[show]

Lenition[show]

Fortition

Epenthesis[show]

Elision[show]

Cheshirization[show]

Assimilation[show]

Dissimilation

Sandhi[show]

Other types[show]

v

t

e

In phonology, voicing (or sonorization) is a sound change where a voiceless consonant becomes voiced due to the influence of its

phonological environment; shift in the opposite direction is referred to as devoicing or desonorization. Most commonly, the change is

a result of sound assimilation with an adjacent sound of opposite voicing, but it can also occur word-finally or in contact with a

specific vowel.

For example, English suffix -s is pronounced [s] when it follows a voiceless phoneme (cats), and [z] when it follows a voiced

phoneme (dogs).

[1]

This type of assimilation is called progressive, where the second consonant assimilates to the first; regressive

assimilation goes in the opposite direction, as can be seen in have to [hft].

Contents

1 English

2 Syllabic voicing and devoicing

o 2.1 Voicing assimilation

o 2.2 Final devoicing

3 Sound change

4 References

5 Bibliography

English

English no longer has a productive process of voicing stem-final fricatives when forming noun-verb pairs or plural nouns.

belief - believe

life - live

proof - prove

strife - strive

thief - thieve

ba[] - ba[]e

brea[] - brea[]e

mou[] (n.) - mou[] (vb.)

shea[] - shea[]e

wrea[] - wrea[]e

hou[s]e (n.) - hou[z]e (vb.)

u[s]e (n.) - u[z]e (vb.)

Synchronically, the assimilation at morpheme boundaries is still productive, such as in:

[2]

cat + s cats

dog + s do[z]

miss + ed mi[st]

whizz + ed whi[zd]

The voicing alternation found in plural formation is losing ground in the modern language,

[citation needed]

, and of the alternations listed

below many speakers retain only the [f-v] pattern, which is supported by the orthography. This voicing is a relic of Old English, the

unvoiced consonants between voiced vowels were 'colored' with voicing. As the language became more analytic and less inflectional,

final vowels/syllables stopped being pronounced. For example, modern knives is a one syllable word instead of a two syllable word,

with the vowel 'e' not being pronounced. However, the voicing alternation between [f] and [v] still occurs.

knife - knives

leaf - leaves

wife - wives

wolf - wolves

The following mutations are optional

[citation needed]

:

ba[] - ba[]s

mou[] - mou[]s

oa[] - oa[]s

pa[] - pa[]s

you[] - you[]s

hou[s]e - hou[z]es

Sonorants (/l r w j/) following aspirated fortis plosives (that is, /p t k/ in the onsets of stressed syllables unless preceded by /s/) are

devoiced such as in please, crack, twin, and pewter.

[3]

Syllabic voicing and devoicing

Voicing assimilation

Main article: Assimilation (linguistics)

In many languages including Polish and Russian, there is anticipatory assimilation of unvoiced obstruents immediately before voiced

obstruents. For example, Russian 'request' is pronounced [prozb] (instead of *[prosb]) and Polish proba 'request' is

pronounced [prba] (instead of *[prba]). This process can cross word boundaries as well, for example Russian [dod

b] 'daughter would'.

Final devoicing

Main article: Final-obstruent devoicing

Final devoicing is a systematic phonological process occurring in languages such as German, Dutch, Polish, and Russian, among

others. In these languages, voiced obstruents in the syllable coda or at the end of a word become voiceless.

Sound change

Voicing of initial letter is a process of historical sound change where voiceless consonants become voiced at the beginning of a word.

For example, modern German sagen [zan], Yiddish [zn], and Dutch zeggen [z] (all "say") all begin with [z], which

derives from [s] in an earlier stage of Germanic, as still attested in English say, Swedish sga [sja], and Icelandic segja [seija].

Some English dialects were affected by this as well, but it is rare in Modern English. One example is fox (with the original consonant)

compared to vixen (with a voiced consonant)

Final-obstruent devoicing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. Please help to improve

this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2009)

Sound change and alternation

Metathesis[show]

Lenition[show]

Fortition

Epenthesis[show]

Elision[show]

Cheshirization[show]

Assimilation[show]

Dissimilation

Sandhi[show]

Other types[show]

v

t

e

Final-obstruent devoicing or terminal devoicing is a systematic phonological process occurring in languages such as German,

Dutch, Russian, Turkish, and Wolof. In such languages, voiced obstruents become voiceless before voiceless consonants and in pausa.

Contents

1 German

2 Dutch

3 Russian

4 English

5 Differences between languages

6 Languages with final-obstruent devoicing

o 6.1 Germanic languages

o 6.2 Romance languages

o 6.3 Slavic languages

o 6.4 Other languages

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

German

In the southern varieties of German, the contrast between homorganic obstruents is rather an opposition of fortis and lenis than an

opposition of voiceless and voiced sounds. Therefore, the term devoicing may be misleading, since voice is only an optional feature of

German lenis obstruents. Likewise, the German term for the phenomenon, Auslautverhrtung, does not refer to a loss of voice and is

better translated as 'final hardening'. However, the German phenomenon is similar to the final devoicing in other languages in that the

opposition between two different kinds of obstruents disappears at the ends of words. The German varieties of the north, and many

pronunciations of Standard German, do distinguish voiced and voiceless obstruents however.

Some examples from German include:

Nouns Verbs

Singular Translation Plural Imperative Translation Infinitive

Bad [bat] bath Bder [bd] red! [et] talk! reden [edn]

Maus [mas] mouse Muse [mz] lies! [lis] read! lesen [lezn]

Raub [ap] robbery Raube [ab] reib! [ap] rub! reiben [abn]

Zug [tsuk] train Zge [tsy] sag! [zak] say! sagen [zan]

Fnf [ff] five Fnfen [fvn]

Dutch

In Dutch and Afrikaans, terminal devoicing results in homophones such as hard 'hard' and hart 'heart' as well as differences in

consonant sounds between the singular and plural forms of nouns, for example golf-golven (Dutch) and golf-golwe (Afrikaans) for

'wave-waves'.

The history of the devoicing phenomenon within the West Germanic languages is not entirely clear but the discovery of a runic

inscription from the early fifth century that shows devoicing

[1]

suggests that its origins are Frankish. Of the old West Germanic

languages, Old Dutch, a descendant of Frankish, is the earliest to show any kind of devoicing, and final devoicing had also occurred in

Frankish-influenced Old French.

Russian

Final-obstruent devoicing can lead to the neutralization of phonemic contrasts in certain environments. For example, Russian

('demon', phonemically /bes/) and ('without', phonemically /bez/) are pronounced identically in isolation as [bes].

The presence of this process in Russian is also the source of the seemingly variant transliterations of Russian names into "-off"

(Russian: -), especially by the French.

English

English does not have phonological final-obstruent devoicing of the type that neutralizes phonemic contrasts; thus pairs like bad and

bat are distinct in all major accents of English. Nevertheless voiced obstruents are devoiced to some extent in final position in English,

especially when phrase-final or when followed by a voiceless consonant (for example, bad cat [bd kt]).

Differences between languages

Devoicing is lexicalized in some languages, purely phonological in others. In Dutch, for example, words that are devoiced in isolation

retain that final devoicing when they are part of a compound: badwater "bath water" has a voiceless /t/, like bad "bath" does by itself,

though the plural baden "baths" has a voiced /d/. Similarly, avondzon "evening sun" has /ts/, though avonden "evenings" has /d/. In

contrast, Slovene does not do this: Voicing depends solely on position and on assimilation with adjacent consonants.

Languages with final-obstruent devoicing

Germanic languages

All modern continental West Germanic languages developed final devoicing, the earliest evidence appearing in Old Dutch around the

9th or 10th century. Gothic (an East Germanic language) also developed final devoicing independently.

Afrikaans

Dutch (also Old and Middle Dutch)

Old and Middle English (for fricatives)

[citation needed]

German and varieties (also Middle High German

[2]

)

Gothic (for fricatives)

Limburgish (for z, g and v)

Low German (also Middle Low German)

Luxembourgish

Of the North Germanic languages Danish, the closest to German, has final devoicing, while Norwegian and Swedish do not. Icelandic

devoices all stops completely, but still has word-final voiced fricatives.

Romance languages

Among the Romance languages, word-final devoicing is common in the Gallo-Romance languages, which tend to exhibit strong

Frankish influence (itself the ancestor of Old Dutch, above).

Catalan

Old French (preserved in certain Modern French inflections such as -if vs. -ive)

Lombard

Occitan

Romansh

Romanian does not have it. Other Romance languages such as Italian rarely have words with final voiced consonants.

Slavic languages

Most Slavic languages exhibit final devoicing, but notably Serbo-Croatian (the tokavian dialect) and Ukrainian do not.

Belarusian

Bulgarian

Czech

Macedonian

Polish

Russian

Serbo-Croatian (Kajkavian and akavian dialects)

Slovak

Slovene

Sorbian

Other languages

Armenian (for stops)

Azerbaijani

Cypriot Greek as opposed to Standard Modern Greek

Georgian (for stops)

Korean (nuanced; see Korean phonology)

Lithuanian

Maltese

Marshallese (in common articulation only; there is no phonemic contrast between voiceless and voiced obstruents)

Mongolian

[citation needed]

Tok Pisin

Turkish (for stops)

Yaghnobi

Note: Hungarian, which lies geographically between Germanic and Slavic languages, does not have it.

See also

Initial-consonant voicing

Surface filter

Vowel harmony is a type of long-distance assimilatory phonological process involving vowels that occurs in some languages. In languages with

vowel harmony, there are constraints on which vowels may be found near each other.

he term vowel harmony is used in two different senses.

In the first sense, it refers to any type of long distance assimilatory process of vowels, either progressive or regressive. When used in

this sense, the term vowel harmony is synonymous with the term metaphony.

In the second sense, vowel harmony refers only to progressive vowel harmony (beginning-to-end). For regressive harmony, the term

umlaut is used. In this sense, metaphony is the general term while vowel harmony and umlaut are both sub-types of metaphony. The

term umlaut is also used in a different sense to refer to a type of vowel gradation. This article will use "vowel harmony" for both

progressive and regressive harmony.

"Long-distance"

Harmony processes are "long-distance" in the sense that the assimilation involves sounds that are separated by intervening segments

(usually consonant segments). In other words, harmony refers to the assimilation of sounds that are not adjacent to each other. For

example, a vowel at the beginning of a word can trigger assimilation in a vowel at the end of a word. The assimilation occurs across

the entire word in many languages. This is represented schematically in the following diagram:

before

assimilation

after

assimilation

V

a

CV

b

CV

b

C V

a

CV

a

CV

a

C (V

a

= type-a vowel, V

b

= type-b vowel, C = consonant)

In the diagram above, the V

a

(type-a vowel) causes the following V

b

(type-b vowel) to assimilate and become the same type of vowel

(and thus they become, metaphorically, "in harmony").

The vowel that causes the vowel assimilation is frequently termed the trigger while the vowels that assimilate (or harmonize) are

termed targets. When the vowel triggers lie within the root or stem of a word and the affixes contain the targets, this is called stem-

controlled vowel harmony (the opposite situation is called dominant).

[1]

This is fairly common amongst languages with vowel

harmony

[citation needed]

and may be seen in the Hungarian dative suffix:

Root Dative Gloss

vros vros-nak 'city'

rm rm-nek 'joy'

The dative suffix has two different forms -nak/-nek. The -nak form appears after the root with back vowels (The vowel expected to be

used is a but this is a front vowel, therefore the vowel must be pronounced as an because and o are both back vowels). The -nek

form appears after the root with front vowels ( and e are front vowels).

Features of vowel harmony

Vowel harmony often involves dimensions such as

Vowel height (i.e. high, mid, or low vowels)

Vowel backness (i.e. front, central, or back vowels)

Vowel roundedness (i.e. rounded or unrounded)

Tongue root position (i.e. advanced or retracted tongue root, abbrev.: ATR)

Nasalization (i.e. oral or nasal) (in this case, a nasal consonant is usually the trigger)

In many languages, vowels can be said to belong to particular sets or classes, such as back vowels or rounded vowels. Some languages

have more than one system of harmony. For instance, Altaic languages are proposed to have a rounding harmony superimposed over a

backness harmony.

Even amongst languages with vowel harmony, not all vowels need participate in the vowel conversions; these vowels are termed

neutral. Neutral vowels may be opaque and block harmonic processes or they may be transparent and not affect them.

[2]

Intervening

consonants are also often transparent.

Finally, languages that do have vowel harmony often allow for lexical disharmony, or words with mixed sets of vowels even when an

opaque neutral vowel is not involved. van der Hulst & van de Weijer (1995) point to two such situations: polysyllabic trigger

morphemes may contain non-neutral vowels from opposite harmonic sets and certain target morphemes simply fail to harmonize.

[3]

Many loanwords exhibit disharmony. For example, Turkish vakit, ('time' [from Arabic waqt]); *vakt would have been expected.

Harmony processes are "long-distance" in the sense that the assimilation involves sounds that are separated by intervening segments

(usually consonant segments). In other words, harmony refers to the assimilation of sounds that are not adjacent to each other. For

example, a vowel at the beginning of a word can trigger assimilation in a vowel at the end of a word. The assimilation sometimes

occurs across the entire word. This is represented schematically in the following diagram:

before

assimilation

after

assimilation

V

a

CV

b

CV

b

C V

a

CV

a

CV

a

C

(Va = type-a vowel, Vb = type-b vowel, C =

consonant)

In the diagram above, the V

a

(type-a vowel) causes the following V

b

(type-b vowel) to assimilate and become the same type of vowel

(and thus they become, metaphorically, "in harmony").

The vowel that causes the vowel assimilation is frequently termed the trigger while the vowels that assimilate (or harmonize) are

termed targets. In most languages, the vowel triggers lie within the root of a word while the affixes added to the roots contain the

targets. This may be seen in the Hungarian dative suffix:

Root Dative Gloss

vros vros-nak "city"

rm rm-nek "joy"

The dative suffix has two different forms -nak/-nek. The -nak form appears after the root with back vowels (a and o are both back

vowels). The -nek form appears after the root with front vowels ( and e are front vowels).

Another example: Turkish araba (car) pluralises to arabalar but tren (train) pluralises to trenler.

Harmony assimilation may spread either from the beginning of the word to the end or from the end to the beginning. Progressive

harmony (a.k.a. left-to-right harmony) proceeds from beginning to end; regressive harmony (a.k.a. right-to-left harmony) proceeds

from end to beginning. Languages that have both prefixes and suffixes often have both progressive and regressive harmony.

Languages that primarily have prefixes (and no suffixes) usually have only regressive harmony and vice versa for primarily

suffixing languages.

Features of vowel harmony

Vowel harmony often involves dimensions such as

Vowel height (i.e. high, mid, or low vowels)

Vowel backness (i.e. front, central, or back vowels)

Vowel roundedness (i.e. rounded or unrounded)

tongue root position (i.e. advanced or retracted tongue root, abbrev.: ATR)

Nasalization (i.e. oral or nasal) (in this case, a nasal consonant is usually the trigger)

In many languages, vowels can be said to belong to particular classes, such as back vowels or rounded vowels, etc. Some languages

have more than one system of harmony. For instance, Altaic languages have a rounding harmony superimposed over a backness

harmony.

In some languages, not all vowels participate in the vowel conversions these vowels are termed either neutral or transparent.

Intervening consonants are also often transparent. In addition to these transparent segments, many languages have opaque vowels that

block vowel harmony processes.

Finally, languages that do have vowel harmony sometimes have words that fail to harmonize. This is known as disharmony. Many

loanwords exhibit disharmony, either within a root (e.g., Turkish/Turkic vakit/waqit, "time" [from Arabic waqt], where vak?t/waq?t

would have been expected) or in suffixes (e.g., Turkish saat-ler "(the) hours" [hour-PL, from Arabic s`a], where saat-lar would have

been expected). In Turkish, disharmony tends to disappear through analogy, especially within loanwords. Suffixes drop disharmony to

a lesser extent, e.g. Hsn (a man's name) < previously Hsni, from Arabic husn; mslmn "Moslem, Muslim (adj. and n.)" <

mslimn, from Arabic muslim).

Vowel harmony & umlaut terminology

The term vowel harmony is used in two different senses, explained below.

In the first sense, vowel harmony refers to any type of vowel harmony: that is, both progressive and regressive vowel harmony. When

used in this sense, the term vowel harmony is synonymous with the term metaphony.

In the second sense, vowel harmony refers only to progressive vowel harmony (beginning-to-end). For regressive harmony, the term

umlaut is used. In this sense, metaphony is the general term while vowel harmony and umlaut are both sub-types of metaphony. (Note

that the term umlaut is also used in a different sense to refer to a type of vowel gradation.)

Vowel harmony is a type of assimilatory phonological process involving vowels separated by consonantsi. e., not adjacent to each

otherthat occurs in some languages. In languages with vowel harmony, there are constraints on which vowels may be found in

adjacent or succeeding syllables. For example, a vowel at the beginning of a word can trigger assimilation in a vowel at the end of a

word. The Uralic group (like Finnish and Hungarian) and Turkic (like Turkish and Tatar) are prominent instances of language families

with vowel harmony. Thus in Hungarian, vros city has the dative form vrosnak, whereas rm joy has rmnek: the dative suffix

has two different forms -nak/-nek. The -nak form appears after the root with back vowels (a and o are both back vowels), whereas -nek

appears after the root with front vowels ( and e are front vowels).

English does not have vowel harmony as a regular phenomenon, but a trace of this process may account for the strange case of the

common mispronunciation in both British and American English of the verb lambaste as [lambst], which is a compound consisting of

the verbs lam and baste, both of which mean to beat soundly, thrash, cudgel. Since the pronunciation of the second unit baste is

invariably [byst], the pronunciation of the compound ought not to vary from [lambyst], but does anyway. Only vowel harmony,

where the vowel of lam influences that of baste, suggests itself as an explanation for this deviation.

- See more at: http://languagelore.net/?p=2463#sthash.2kEV3VPY.dpuf

Umlaut may refer to:

Umlaut (linguistics), a sound change where a vowel was modified to conform more closely to the vowel in the next syllable

o I-mutation, a specific type of umlaut triggered by a following high front vowel, e.g. /i/

Germanic umlaut, a prominent instance of i-mutation in the history of the Germanic languages

o Umlaut vowel, any front rounded vowel (because such vowels appeared in the Germanic languages as a result of

Germanic umlaut)

o A-mutation and u-mutation (disambiguation), other umlaut processes operating in the history of various Germanic

lanuages

Umlaut (diacritic), a pair of dots () above a vowel, used in various languages; originally used to indicate vowels resulting from

Germanic umlaut

o Metal umlaut, the same diacritic in names of heavy metal or hard rock bands for effect

Lars Umlaut, a character playable in the Guitar Hero series of music video games

Umlut (born 1968), Clinton McKinnon's experimental Australian rock band

Umlaut (software), an open source link resolver front-end for libraries

mlaut (band), a band on CrimethInc

Community

Word of the day

Random word

Log in or Sign up

umlaut

Define

Relate

List

Discuss

See

Hear

umlaut

Define

Relate

List

Discuss

See

Hear

Love

Definitions

from The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th Edition

n. A change in a vowel sound caused by partial assimilation especially to a vowel or semivowel occurring in the following syllable.

n. A vowel sound changed in this manner. Also called vowel mutation.

n. The diacritic mark () placed over a vowel to indicate an umlaut, especially in German.

transitive v. To modify by umlaut.

transitive v. To write or print (a vowel) with an umlaut.

from Wiktionary, Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License

n. An assimilatory process whereby a vowel is pronounced more like a following vocoid that is separated by one or more consonants.

n. The umlaut process (as above) that occurred historically in Germanic languages whereby back vowels became front vowels when

followed by syllable containing a front vocoid (e.g. Germanic lsi > Old English ls(i) > Modern English lice).

n. A vowel so assimilated.

n. The diacritical mark ( ) placed over a vowel, usually when it indicates such assimilation.

v. To place an umlaut over a vowel.

from the GNU version of the Collaborative International Dictionary of English

n. The euphonic modification of a root vowel sound by the influence of a, u, or especially i, in the syllable which formerly followed.

from The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia

n. In philology, the German name, invented by Grimm, for a vowel-change in the Germanic languages, brought about by the influence of

a vowel in the succeeding syllable: namely, of the vowel i, modifying the preceding vowel in the direction of e or i, and of the vowel u,

modifying the preceding vowel toward a or u.

In philology, to form with the umlaut, as a form; also, to affect or modify by umlaut, as a sound.

from WordNet 3.0 Copyright 2006 by Princeton University. All rights reserved.

n. a diacritical mark (two dots) placed over a vowel in German to indicate a change in sound

Etymologies

German : um-, around, alteration (from Middle High German umb-, from umbe, from Old High German umbi) + Laut, sound (from Middle High

German lt, from Old High German hlt).

(American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition)

From German Umlaut, from um ("around") + Laut ("sound"), from Old High German hlut. (Wiktionary)

Examples

What happens in umlaut is that a back vowel is modified so as to have the form of the corresponding front vowel when there is

a front vowel in the following syllable; this typically happens in plural forms of nouns, comparative forms of adjectives, and

other words that have suffixes, so Mann (man) becomes Mnner (men), lang (long) becomes lnger (longer), and Tod (death)

becomes tdlich (deathly, lethal).

Umlaut

The preposition um means around or surrounding, but as a prefix the word has the idea of changing or modifying; laut means

sound, so an umlaut is a modified sound.

Umlaut

a mark () used as a diacritic over a vowel, as , , , to indicate a vowel sound different from that of the letter without the diacritic,

especially as so used in German.

Compare dieresis.

2.

Also called vowel mutation. (in Germanic languages) assimilation in which a vowel is influenced by a following vowel or semivowel.

verb (used with object)

3.

to modify by umlaut.

4.

to write an umlaut over.

Origin

1835-1845

1835-45; < German, equivalent to um- about (i.e., changed) + Laut sound

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Dictionary, Random House, Inc. 2014.

Cite This Source

Examples from the web for umlaut

Provision is made for an umlaut and other diacritical marks, but these are dropped in common usage.

British Dictionary definitions for umlaut

Umlaut

Palatal umlaut

Palatal umlaut is a process whereby short e, eo, io appear as i (occasionally ie) before final ht, hs, h. Examples:

riht "right" (cf. German recht)

cniht "boy" (mod. knight) (cf. German Knecht)

siex "six" (cf. German sechs)

briht, bryht "bright" (cf. non-metathesized Old English forms beorht, (Anglian) berht, Dutch brecht)

hlih "(he) laughs" < *hleh < *hlhi + i-mutation < Proto-Germanic *hlahi (cf. hliehhan "to laugh" < Proto-Germanic *hlahjan)

/mlat/

noun

1.

the mark () placed over a vowel in some languages, such as German, indicating modification in the quality of the vowel Compare

diaeresis

2.

(esp in Germanic languages) the change of a vowel within a word brought about by the assimilating influence of a vowel or

semivowel in a preceding or following syllable

Word Origin

C19: German, from um around (in the sense of changing places) + Laut sound

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Cite This Source

Word Origin and History for umlaut

n.

1852, from German umlaut "change of sound," from um "about" (see ambi- ) + laut "sound," from Old High German hlut (see listen ).

Coined 1774 by poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) but first used in its current sense 1819 by linguist Jakob Grimm (1785-

1863).

Now an umlaut is masculine, but an accent mark ...?

An Open Letter to David Horowitz

Okay, so they're spelling it differently (the umlaut is a nice touch, I must admit) ... but still!

Entertainment Weekly's PopWatch

"The computer thought the umlaut was the last letter in the alphabet and removed everyone else's names," he said.

The Independent - Frontpage RSS Feed

Probably because of that strange little trema (a French kind of umlaut or diaeresis) over the "e".

Brooks Peters: Le Mot Juiced

Everywhere that his name appears in the printed text, the letter "u" is marked with two dots above it (called an 'umlaut') to

show that it is pronounced differently from the way the unmarked vowel is normally pronounced.

George Mller of Bristol And His Witness to a Prayer-Hearing God

For those of you unfamiliar with German diacritics, "umlaut" is the name for the two dots above a vowel.

Express Milwaukee

#458783: Doesn't start if installed into a directory with an "umlaut"

GnuCash News

By the way, there is no "umlaut" ) in the name Under Byen - we don't have umlauts in Danish ;-)

Music While Painting

Related Words

Log in or sign up to add your own related words.

synonyms (2)

Words with the same meaning

1. trema

2. vowel harmony

hypernyms (2)

Words that are more generic or abstract

1. diacritic

2. diacritical mark

tags (1)

Free-form, user-generated categorization

1. vccvvc

Log in or sign up to add your own tag.

reverse dictionary (15)

Words that contain this word in their definition

1. umlaut

2. modify

3. mutation

4. umlaut

5. umlaut

6. umlaut

7. umlauted

8. mutation

9. Oe

some English language terms have letters with diacritical marks.

[1]

Most of the words are loanwords from French, with others

coming from Spanish, German, or other languages.

[2]

Some are however originally English, or at least their diacritics are.

10. Proper nouns are not generally counted as English terms except when accepted into the language as an eponym - such as

Geiger-Mller tube, or the English terms roentgen after Wilhelm Rntgen, and biro after Lszl Br, in which case any

diacritical mark is often lost.

11. umlaut n., v.t., umlaut-mark n.

12. from Umlaut "change of sound": also called vowel modification, mutation or inflection; the change of a vowel sound (e.g.,

mousemice, goosegeese, langlauflanglufer); the vowel altered in this way; the diacritical mark consisting of two dots

() over a modified vowel; to modify by umlaut; to write an umlaut over. [German < um- "about, changed" < Middle High

German umbe < Middle High German umbi + Laut "sound" < Middle High German lut, coined by Jacob Grimm of the

Brothers Grimm.] This entry suggested by Aldorado Cultrera.

The diacritic marks umlaut and dieresis [chiefly Am.] (also spelled diaeresis [chiefly Br.]) are identical in appearance but

different in function. The dieresis (Greek "to take apart") indicates that the vowel so marked is to be pronounced separately

from the one preceeding it (e.g., nave, Nol) or that the vowel should be sounded when it might otherwise be silent (e.g.,

Bront).

The origin of the German umlaut is an abbreviated "e", i.e. the vowel is influenced by the following (semi-)vowel "e" in a

process called apophany, therefore the correct transliteration of an umlaut is to use an "e" after the vowel. Umlauts occur

mostly in Germanic languages but also for example in Finnish. When German words with umlauts are assimilated into the

English language, they sometimes keep their umlauts (e.g., doppelgnger, Flgelhorn, fhn, Der Freischtz, fhrer, jger,

kmmel, Knstlerroman, schweizerkse, ber-), but often are simply written without the diacritic (e.g., doppelganger,

flugelhorn, Der Freischutz, yager), and less often are correctly transliterated using an "e" (e.g., foehn, fuehrer, jaeger, loess).

Of course, sometimes more than one spelling makes its way into English. Muesli could have originated from Mesli or Msli,

so it's not clear if the umlaut was lost or transliterated.

Rhotacism (/rotszm/)

[1]

may refer to an excessive or idiosyncratic use of the letter r, the inability to pronounce (or difficulty in

pronouncing) r, or the conversion of another consonant into r.

The term comes from the Greek letter rho, denoting "r"

In linguistics, rhotacism or rhotacization is the conversion of a consonant (usually a voiced alveolar consonant /z/, /d/, /l/, or /n/) to a rhotic

consonant in a certain environment. The most common may be of /z/ to /r/.

[2]

English

Pronouncing the letter "r" is common in many dialects of American, Canadian, Irish, Welsh and Scottish English and less common in

the English of most of England, Australia, and New Zealand. Lenition of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to [d] or [] is also common in many

modern English dialects (e.g. <got a lot of> (phonemically /gt lt/) becoming [gd ld] or [g l]). Contrast is maintained

with // because it is never realized as a flap in these dialects of English.

[2]

hotacism (countable and uncountable, plural rhotacisms)

1. An exaggerated use of the sound of the letter R.

2. (countable, linguistics): A linguistic phenomenon in which a consonant changes into an R, such as Latin flos becoming florem

in the accusative case.

3. Inability to pronounce the letter R; derhotacization. [ quotations ]

rhotacism

Define

Relate

List

Discuss

See

Hear

Love

Definitions

from Wiktionary, Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License

n. An exaggerated use of the sound of the letter R.

n. : A linguistic phenomenon in which a consonant changes into an R, such as Latin flos becoming florem in the accusative case.

n. Inability to pronounce the letter R; derhotacization.

from the GNU version of the Collaborative International Dictionary of English

n. An oversounding, or a misuse, of the letter r; specifically (Phylol.), the tendency, exhibited in the Indo-European languages, to change

s to r, as wese to were.

from The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia

n. Too frequent use of r.

n. Erroneous pronunciation of r; utterance of r with vibration of the uvula.

n. Conversion of another sound, as s, into r.

n. Also spelled rotacism.

Etymologies

From New Latin rhotacismus ("excessive or peculiar use of [r], especially the conversion of another sound (usually [s] or [z]) to [r]"), from Ancient

Greek * , from (rhotakiz, "I incorrectly use "), from (rh, "rho (the Greek equivalent of r)") (Wiktionary)

Examples

Sounds like proper Ringlish if you'll excuse an exaggerated intervocalic rhotacism.

languagehat.com: UNCLEFTISH BEHOLDING.

Since then he's discussed rhotacism in Venezuela (eg \er negro\ for el negro 'the black one'), lesmo in Madrid (the use of the

indirect pronoun as a direct object), and Occitan/Provenal, among other things.

languagehat.com: ROMANIKA.

They comprise chiefly: sigmatism or imperfect pronunciation of s; rhotacism or imperfect pronunciation of r; lambdacism or

imperfect pronunciation of l; gam -

The Montessori Method

They show more plainly (at least concerning rhotacism) than my own notes, some imperfections of articulation of the child in

the second year, which occur, however, only in single individuals.

The Mind of the Child, Part II The Development of the Intellect, International Education Series Edited By William T. Harris,

Volume IX.

She also speaks with a rhotacism, mirroring that 'classless' pronunciation of Jonathan Ross and David Bellamy.

Anorak News

ld English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative since Old English is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very

large corpus of the language, and the orthography apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully, so it is not difficult to draw

certain conclusions about the nature of Old English phonology.

Consonant allophones

The sounds marked in parentheses in the table above are allophones:

[d] is an allophone of /j/ occurring after /n/ and when geminated

o For example, senan "to singe" is [sendn] < *sangijan

o and bry "bridge" is [brydd] < /bryjj/ < *bruggj < *bruj

*+ is an allophone of /n/ occurring before /k/ and //

o For example, hring "ring" is [ri]; *+ did not occur alone word-finally in Old English as it does in Standard Modern English.

(Some dialectal forms of Modern English, e.g. in Northern England, retain the Old English pattern.)

[v, , z] are allophones of /f, , s/ respectively, occurring between vowels or voiced consonants.

o For example, stafas "letters" is [stvs] < /stfs/, smias "blacksmiths" is [smis] < /smis/, and hses "house (genitive)" is

[huzes] < /huses/.

[, x] are allophones of /h/ occurring in coda position after front and back vowels respectively. The evidence for the allophone [] after

front vowels is indirect, as it is not indicated in the orthography. Nevertheless, the fact that there was historically a fronting of *k to /t/

and of * to /j/ after front vowels makes it very likely. Moreover, in late Middle English, /x/ sometimes became /f/ (e.g. tough, cough),

but only after back vowels, never after front vowels. This is explained if we assume that the allophone [x] sometimes became [f] but the

allophone [] never did.

o For example, cniht "boy" is [knit], while eht "thought" is [jeoxt]

The sequences /hw hl hn hr/ were realised as [ l n r].

[] is an allophone of // occurring after a vowel or liquid. Historically, [] is older, and originally appeared in word-initial position as

well; for Proto-Germanic (PGmc) and probably the earliest Old English it makes more sense to say that [] is an allophone of // after a

nasal or when geminated. But after [] became [] word-initially, it makes more sense to treat the stop as the basic form and the

fricative as the allophonic variant.

o For example, dagas "days" is [ds] and burgum "castles (dative)" is [burum]

/l/ and /r/ apparently had velarized allophones [] and [], or similar, when followed by another consonant. This conclusion is based on

the phenomena of breaking and retraction, which appear to be cases of assimilation to a following velar consonant.

Vowels

Monophthongs

Most dialects of Old English had 7 vowels, each with a short and long version, for a total of 14 monophthongs. Certain dialects add an

eighth vowel, for a total of 16.

Front Back

unrounded rounded unrounded rounded

Close i i y y

u u

Mid e e ( )

o o

Open

The front mid rounded vowels /()/ occur in some dialects of Old English, but not in the best attested Late West Saxon dialect.