Aboriginal Education Essay

Diunggah oleh

appy greg100%(2)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (2 suara)

2K tayangan7 halamanEDUC5429

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniEDUC5429

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(2)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (2 suara)

2K tayangan7 halamanAboriginal Education Essay

Diunggah oleh

appy gregEDUC5429

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 7

EDUC5429 Aboriginal Education

Assignment 2 Major Essay Aithne Dell 20539099

I ncorporating supporting evidence from a range of relevant literature, discuss how your

understanding of the impact of culture, cultural identity and linguistic background on the

education of students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait I slander backgrounds will inform

your practices as a teacher.

Education within Australia is not equal for all children. Student engagement in formal

educational settings and school retention rates for Aboriginal children remain significantly lower

than those for non-Indigenous students. There are a number of factors which may contribute to

this disparity. Language difficulties can arise within the classroom, with differences in dialect

not being well understood by those within the education system. Aboriginal English is spoken by

many Indigenous children, and while it bears a strong similarity to Standard Australian English,

there are differences which are often considered in a negative manner when they used in the

classroom. Stigmatising these differences without an acknowledgement of the validity of the

dialect shows a lack of understanding and respect for Aboriginal culture, which can be highly

detrimental to a students sense of identity (Eades, as cited in Sharifian, 2005). This underlying,

covert racism is also often present throughout Australias political policies, historically relating

to education policy as well. This has caused ongoing issues, with previous generations now

unable to help those who are currently receiving education. Cultural issues caused by

intergenerational trauma and mistreatment are often reflected in childrens thinking and

ideologies, which can affect classroom learning. Additionally, there are a number of cultural

factors which can contribute to family mobility, causing students to be absent from, or itinerant

in, their schooling. As an ongoing factor, this can cause students to miss considerable periods of

their education, causing gaps in their understanding and making it difficult for them to continue

into the higher levels. Through factors of culture and cultural identity not being accepted or

understood by the Australian schooling system, many Aboriginal students are being denied an

appropriate and adequate education.

One key factor which can inhibit a childs ability to succeed in the classroom is language

barriers. In many cases, Aboriginal children in the classroom speak a different dialect of English,

Aboriginal English. This dialect has been documented in widely separated parts of Australia

and, despite some stylistic and regional variation, is remarkably consistent across the continent

(Malcom, 2013, p.267) While the use of Aboriginal English may not inhibit communication,

there are instances where understanding can be affected. In particular, children who are not yet

competent in the art of code-switching (Taylor, 2010) between Aboriginal English and a more

formal variation of Australian English may struggle to produce work which is considered

acceptable in school. A survey of Aboriginal children within Western Australia found that those

who spoke Aboriginal English were three times more likely to perform at a low academic level

(Zubrick et al., 2006). While children need to develop an understanding of Standard Australian

English, it remains important for the teachers to acknowledge the validity of Aboriginal English

as a dialect spoken widely throughout Australia. Malcom (2013) states that it, as a language,

provides a vehicle for the common expression of Aboriginal identity (p.267), and Oliver,

Rochecouste, Vanderford and Grote (2011) comment that the ability to speak the dialect may be

necessary for ongoing acceptance within their own communities (p.62). Direct and repeated

condemnation of the dialect, or constant correction without acknowledgement of the need to

code-switch may be detrimental to Aboriginal students identity (Malcom, 2003). It is also noted

that the maintenance of a students first language is fundamental to their success in learning a

second language (Oliver et al., 2011, p.61). Effort must be taken, therefore, to avoid the

dismissal of different dialects such as Aboriginal English. An alternative approach is provided

through the ABC of Two-Way Literacy and Learning Capacity Building Project (as cited in

McHugh & Konigsberg, 2004). The initial step here is to accept Aboriginal English in the

classroom, before bridging to Standard Australian English (McHugh & Kinigsberg, 2004, p.9).

Rather than promoting the teaching of Aboriginal English, this project aims to engage students

and seeks to improve self-esteem, attention, desire to learn, sense of place in learning

environment, and retention among non-standard dialect speakers by utilising the home dialect

(McHugh & Konigsberg, 2004, p.10). Additionally, making the differences between the different

dialects explicit and encouraging the children in the class to know when and how to use each can

help students to learn to code-switch between Aboriginal English and Standard Australian

English. Furthermore, it is important to contact and consult with those who have local knowledge

about the area and the languages and dialects used, so as to help students build their bi-

dialectalism (Woolfolk & Margetts, 2013). Through approaches such as these, teachers can

support each Aboriginal childs cultural identity, both within the classroom and the community,

while also allowing them opportunities to develop their understanding of Standard Australian

English.

Australias history of racism towards Aboriginal people continues to impact education policy and

procedures today. Intergenerational trauma and disadvantage, resulting from racist policies of

discrimination, neglect or forced assimilation, throughout Aboriginal populations causes ongoing

issues which can be difficult to overcome. Historically, Australias record of denying civil rights,

including all but basic education, to Aboriginal people has a continuing impact today, with older

generations unable to help or support those currently receiving an education. 70 years ago, it was

estimated that fewer than 10 per cent of Indigenous children throughout Australia were

attending state schools, a further 25 per cent were in church-based missions and the remainder

that is nearly two-thirds of Indigenous children received no education whatsoever (Neville, as

cited in Gray & Beresford, 2008, p.205). Gray and Beresford (2008) claim that many of the

attempts to rectify the educational disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal people have been

embedded in racism, deficit theory and assimilation (p.207). Programmes of assimilation and

integration which were embedded into the curriculum following the Second World War,

however, served to reject Aboriginal culture, and continuing the issues with childrens

disengagement from formal schooling (Gray & Beresford, 2008). Furthermore, despite recent

and ongoing attempts at reconciliation, the Australian political system has been reluctant to

empower Indigenous people to be self-determining (Gray & Beresford, 2008, p.214). The

education system for all is therefore still developed predominately from a white, Euro-centric

background, which can leave some Aboriginal children at a disadvantage. Winch (1998)

describes how [f]rom the childrens perspective all the rules have changed so that they become

confused by the different cultural approaches and fall behind in their school workWhite

Australian school children have almost always been reared in a similar system to the teacher

(p.23). This initial imbalance shapes childrens enduring experiences of the schooling system.

Approaches, such as actively supporting Indigenous culture within the classroom and working

with local Aboriginal communities and knowledge can help to bridge this gap between students.

By incorporating Aboriginal perspectives through local knowledge and works created by

Aboriginal authors, artists and experts, the schooling of all children in the classroom can be

benefitted.

Student mobility has vast impacts on education. Learning is considered to be in many ways

sequential, and [m]uch of the school syllabus is built on fundamental concepts where each is a

link in a chain of learning. The underlying premise is that the student attends school on a regular

basis (de Plevitz, 2007, p. 57). However, for students who do not attend school regularly, this

can cause difficulties when attempting to catch up on missing days and especially when moving

on to higher level topics before the basics are covered. Studies conducted in Yamatji country in

Western Australia show that vast numbers of students are regularly moving. Examples from Cue

and Mt Magnet suggest that between 60 and 100 per cent of the school population was

itinerant, and in nearby Meekatharra administrators suggested that at least 40 per cent of the

school population were not in regular attendance (Prout, 2009, p.44). These imply that vast

numbers of Indigenous students within this area, and within Western Australia in general, are

affected by familial mobility or spatiality both long-term and temporary movement (Prout,

2009). A number of factors can be considered when accounting for this movement, with Prout

(2009) citing factors of sociocultural obligations to be the cause of such mobility, such as

attendance at ceremonies or visiting families, familial or legal conflicts. De Plevitz (2007) raises

the issues of students needing to attend funerals of family members, leading to absence from

school. A failure to account for student mobility and to develop means to combat the issues

arising from children not receiving a consistent education likely contributes to the low rate of

completion of secondary schooling amongst Aboriginal populations. While statistics for student

retention from Year 8 through to 12 are slowly increasing, the numbers are still far below those

of non-Indigenous students within Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012; Milroy,

2011; Schwab, 1999). By being aware of Aboriginal cultural factors while lead to mobility,

schools, both at the administrative and teacher levels, can begin to develop ways to work around

this movement, so that it is not to the detriment of the students education.

One of the key factors listed by the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, is the

importance of knowing your students and how they learn (Australian Institute for Teaching

and School Leadership, 2014). Incorporated in this, is the need to develop strategies specific to

addressing the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in order to assist in them

to develop their own abilities and talents throughout school. By acknowledging issues of

language diversity within Australia, and the presence of different dialects, as well as cultural

factors which can lead to school absence due to mobility or stress in the classroom as a result of

a Western education system, teachers can begin to adapt to the needs of their learners. Through a

range of approaches, and especially through incorporating local Aboriginal perspectives into

their teaching and learning, the needs of Aboriginal students in the classroom can be supported.

Reference List

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Education: School retention. Retrieved from

http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/lookup/4704.0Chapter350Oct+2010.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2014). Australian

Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from

http://www.teacherstandards.aitsl.edu.au/OrganisationStandards/Organisation.

De Plevitz, L. (2007). Systemic racism: The hidden barrier to educational success for

Indigenous school students. Australian Journal of Education, 51(1), 54-71.

Gray, J. & Beresford, Q. (2008). A formidable challenge: Australias quest for equity in

Indigenous education. Australian Journal of Education, 52(2), 197-223.

Malcom, I.G. (2003). English language and literacy development and home language support:

Connections and directions in working with Indigenous Students. TESOL in Context, 13(1), 5-18.

Malcom, I.G. (2013). Aboriginal English: Some grammatical features and their implications.

Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 36(3), 267-284.

Milroy, J. (2011, August). Incorporating and understanding different ways of knowing in the

education of Indigenous students. Paper presented at the ACER Research Conference 2011

Indigenous Education: Pathways to Success. Retrieved from

http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2011/8august/.

McHugh, M. & Konigsberg, P. (2004, December). Accepting Aboriginal English the ABC of

two-way literacy and learning. Literacy Link, p.9-11. Retrieved from

http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/153087460?versionId=166840106.

Oliver, R., Rochecouste, J., Vanderford, S. & Grote, E. (2011). Teacher awareness and

understandings about Aboriginal English in Western Australia. Australian Review of Applied

Linguistics, 34(1), 60-74.

Prout, S. (2009). Policy, practice and the revolving classroom door: Examining the relationship

between Aboriginal spatiality and the mainstream education system. Australian Journal of

Education, 53(1), 39-53.

Schwab, R.G. (1999). Why only one in three? The complex reasons for low Indigenous school

retention. Canberra: The Australian Natural University.

Sharifian, F. (2005). Cultural conceptualisations in English words: A study of Aboriginal

children in Perth. Language and Education, 19(1), 74-88.

Taylor, A. (2010). Here and now: the attendance issue in Indigenous early childhood education.

Journal of Education Policy, 25(5), 677-699.

Winch, J. (1998). Aboriginal youth. New Doctor, 70, 22-24.

Woolfolk, A. & Margetts,K. (2013). Educational psychology (3rd ed). Sydney: Pearson

Education.

Zubrick, S.R., Silburn, S.R., De Maio, J.A., Shepherd, C., Griffin, J.A., Dalby, R.B., Cox, A.

(2006). The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: Improving the educational

experiences of Aboriginal children and young people. Perth: Curtin University of Technology

and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Aboriginal Education Assignment 2Dokumen10 halamanAboriginal Education Assignment 2bhavneetpruthyBelum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1Dokumen11 halamanAboriginal Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1api-435535701100% (1)

- 2h2018assessment1option1Dokumen9 halaman2h2018assessment1option1api-317744099Belum ada peringkat

- ABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies EssayDokumen9 halamanABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Essayapi-408471566Belum ada peringkat

- Keer Zhang 102085 A2 EssayDokumen13 halamanKeer Zhang 102085 A2 Essayapi-460568887100% (1)

- Assignment 1 Shuo Feng 19185558Dokumen9 halamanAssignment 1 Shuo Feng 19185558api-374345249Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1Dokumen5 halamanAssignment 1api-279841419Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal Education Essay2 FinalDokumen5 halamanAboriginal Education Essay2 Finalapi-525722144Belum ada peringkat

- PLP Edfd462 Assignment 1Dokumen12 halamanPLP Edfd462 Assignment 1api-511542861Belum ada peringkat

- Assessment1Dokumen8 halamanAssessment1api-380735835Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy 19187336 ReflectionDokumen3 halamanAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy 19187336 Reflectionapi-374403345Belum ada peringkat

- 2h 2018 Assessment1 Option2Dokumen7 halaman2h 2018 Assessment1 Option2api-355128961Belum ada peringkat

- Individual Reflection 17456933Dokumen6 halamanIndividual Reflection 17456933api-518663142Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1Dokumen10 halamanAssignment 1api-320762430Belum ada peringkat

- 2H2018Assessment1Option1Dokumen7 halaman2H2018Assessment1Option1Andrew McDonaldBelum ada peringkat

- Standard 2 4 EvidenceDokumen8 halamanStandard 2 4 Evidenceapi-324752028Belum ada peringkat

- Assessment 2Dokumen14 halamanAssessment 2api-297389221Belum ada peringkat

- 2h2019 ReflectionDokumen4 halaman2h2019 Reflectionapi-408336810Belum ada peringkat

- 14285985lauren McgrathDokumen10 halaman14285985lauren Mcgrathapi-411050747Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal Essay 1Dokumen10 halamanAboriginal Essay 1api-357631525Belum ada peringkat

- Interview EvaluationDokumen5 halamanInterview Evaluationapi-317910994Belum ada peringkat

- Academic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisDokumen4 halamanAcademic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisEbony McGowanBelum ada peringkat

- Amy Hawkins Educ9400 Minor AssignmentDokumen9 halamanAmy Hawkins Educ9400 Minor Assignmentapi-427103633Belum ada peringkat

- Easts 735506 12305349emh442 G BryantDokumen12 halamanEasts 735506 12305349emh442 G Bryantapi-370836163Belum ada peringkat

- EssayDokumen13 halamanEssayapi-361229755Belum ada peringkat

- Acrp ReflectionDokumen7 halamanAcrp Reflectionapi-429869768Belum ada peringkat

- Individual ReflectionDokumen4 halamanIndividual Reflectionapi-407620820Belum ada peringkat

- Final Essay Teaching Indigenous Australian StudentsDokumen3 halamanFinal Essay Teaching Indigenous Australian Studentsapi-479497706Belum ada peringkat

- Critical Reflective EssayDokumen8 halamanCritical Reflective Essayapi-374459547Belum ada peringkat

- Bhorne 17787840 Reflectionassessment2Dokumen7 halamanBhorne 17787840 Reflectionassessment2api-374374286Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)Dokumen11 halamanAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)api-355889713Belum ada peringkat

- What Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Dokumen4 halamanWhat Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-465449635Belum ada peringkat

- Acrp Essay - Assessment 1Dokumen13 halamanAcrp Essay - Assessment 1api-368764995Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1 - 102085Dokumen10 halamanAssignment 1 - 102085api-357692508Belum ada peringkat

- RTL 2 AssessmentDokumen50 halamanRTL 2 Assessmentapi-435640774Belum ada peringkat

- Eed408 2Dokumen3 halamanEed408 2api-354631612Belum ada peringkat

- 2h Reflection MurgoloDokumen6 halaman2h Reflection Murgoloapi-368682595Belum ada peringkat

- Rimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 EssayDokumen8 halamanRimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 Essayapi-376717462Belum ada peringkat

- Edfd452 Assessment Task 1 Itp EssayDokumen5 halamanEdfd452 Assessment Task 1 Itp Essayapi-253475393Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 2 - Inclusive Education Part 1: Case StudyDokumen16 halamanAssignment 2 - Inclusive Education Part 1: Case Studyapi-466676956Belum ada peringkat

- Rationale Learning SequenceDokumen15 halamanRationale Learning Sequenceapi-221544422Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-EssayDokumen9 halamanAboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-Essayapi-435791379Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education Critically Reflective Essay Option 1Dokumen13 halamanAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education Critically Reflective Essay Option 1api-408516682Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal Reflection 2 - 2Dokumen6 halamanAboriginal Reflection 2 - 2api-407999393Belum ada peringkat

- 2h2018assessment1option1Dokumen10 halaman2h2018assessment1option1api-432307486Belum ada peringkat

- Wilman R Edpr3004 Asessment 1 Report Sem 1Dokumen10 halamanWilman R Edpr3004 Asessment 1 Report Sem 1api-314401095Belum ada peringkat

- Assignment 3 Differentiation Xyzz CompressedDokumen11 halamanAssignment 3 Differentiation Xyzz Compressedapi-377918453Belum ada peringkat

- Suma2018 Assignment1Dokumen8 halamanSuma2018 Assignment1api-355627407Belum ada peringkat

- ReflectionDokumen5 halamanReflectionapi-408471566Belum ada peringkat

- Klaryse Dam - Essay On The Foundation of Teaching and LearningDokumen12 halamanKlaryse Dam - Essay On The Foundation of Teaching and Learningapi-505539908Belum ada peringkat

- TEAC7001 Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Autumn 2022Dokumen15 halamanTEAC7001 Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Autumn 2022Salauddin MeridhaBelum ada peringkat

- 2h2018 Critical ReflectionDokumen6 halaman2h2018 Critical Reflectionapi-435612649Belum ada peringkat

- Unit Outline Aboriginal FinalDokumen12 halamanUnit Outline Aboriginal Finalapi-330253264Belum ada peringkat

- Acrp ReflectionDokumen4 halamanAcrp Reflectionapi-357644683Belum ada peringkat

- Final EssayDokumen6 halamanFinal Essayapi-375391245Belum ada peringkat

- Emh442 11501113 2 2bDokumen29 halamanEmh442 11501113 2 2bapi-326968990Belum ada peringkat

- Assessment One - AboriginalDokumen13 halamanAssessment One - Aboriginalapi-357662891Belum ada peringkat

- Kristy Snella3Dokumen9 halamanKristy Snella3api-248878022Belum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum FinalDokumen8 halamanAboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum Finalmmccallum88Belum ada peringkat

- Working with Gifted English Language LearnersDari EverandWorking with Gifted English Language LearnersPenilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- HGP Assessment ToolDokumen2 halamanHGP Assessment ToolEric Casanas100% (1)

- Resume by Alyssia Van DuchDokumen4 halamanResume by Alyssia Van Duchavanduc2Belum ada peringkat

- WWWWDokumen8 halamanWWWWwoody woodBelum ada peringkat

- Business ProposalDokumen27 halamanBusiness ProposalWUON BLE The Computer ExpertBelum ada peringkat

- UVa ResumeDokumen3 halamanUVa ResumeThomas BullockBelum ada peringkat

- Academia JulianDokumen7 halamanAcademia JulianMoniq MaresBelum ada peringkat

- Educational Provisions For Learners With Disabilities in IndiaDokumen22 halamanEducational Provisions For Learners With Disabilities in IndiaKishori RaoBelum ada peringkat

- Module 3-Lesson 2Dokumen36 halamanModule 3-Lesson 2Yie YieBelum ada peringkat

- Problems NTDokumen3 halamanProblems NTChirag SinghalBelum ada peringkat

- Final MSCF Brochure Fall 2012Dokumen11 halamanFinal MSCF Brochure Fall 2012Letsogile BaloiBelum ada peringkat

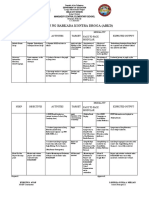

- Mces-Ndep Action Plan 2020-2021Dokumen3 halamanMces-Ndep Action Plan 2020-2021EVELYN AYAPBelum ada peringkat

- Conflicts of Interest in Representation of Public Agencies in Civil MattersDokumen17 halamanConflicts of Interest in Representation of Public Agencies in Civil MattersSLAVEFATHERBelum ada peringkat

- Readability of Selected Literary Texts in English and Level of Mastery in Comprehension Skills of Grade 7: Basis For An Enhanced Reading ProgramDokumen6 halamanReadability of Selected Literary Texts in English and Level of Mastery in Comprehension Skills of Grade 7: Basis For An Enhanced Reading ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Reccomendation LetterDokumen1 halamanReccomendation Letterapi-501250762Belum ada peringkat

- MATh Q3 COT Week3 Day 2Dokumen37 halamanMATh Q3 COT Week3 Day 2En Cy67% (3)

- ST Francis Xavier Catholic Primary SchoolDokumen11 halamanST Francis Xavier Catholic Primary SchoolxavierwebadminBelum ada peringkat

- UmarDokumen10 halamanUmarGuo Heng TanBelum ada peringkat

- FIN 376 - International Finance - DuvicDokumen9 halamanFIN 376 - International Finance - DuvicAakash GadaBelum ada peringkat

- Nathan Hillyer 10 1 2020Dokumen1 halamanNathan Hillyer 10 1 2020api-551118365Belum ada peringkat

- Rosco. R. Educ-8 Week-8Dokumen3 halamanRosco. R. Educ-8 Week-8Jomarc Cedrick Gonzales100% (7)

- Escalation Profile Tommi Forrester - UnidentifiedDokumen1 halamanEscalation Profile Tommi Forrester - Unidentifiedapi-478296665Belum ada peringkat

- Administration and Supervision of Extra Curricular Activities Copies For ClassmatesDokumen3 halamanAdministration and Supervision of Extra Curricular Activities Copies For ClassmatesTrina Lloren LitorjaBelum ada peringkat

- Poudre School District Licensed/Teacher Salary Schedule (T) 2020-2021 School YearDokumen2 halamanPoudre School District Licensed/Teacher Salary Schedule (T) 2020-2021 School YearHeryanto ChandrawarmanBelum ada peringkat

- Jennifer Hunt: ObjectiveDokumen3 halamanJennifer Hunt: Objectiveapi-332574153Belum ada peringkat

- The Great Plebeian CollegeDokumen1 halamanThe Great Plebeian CollegeAnjhiene CambaBelum ada peringkat

- Irtg PDFDokumen8 halamanIrtg PDFgantayatBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan in Math 2Dokumen8 halamanLesson Plan in Math 2Er Win85% (13)

- Chapter 3 Module 4 Lesson 1 Implementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change ProcessDokumen83 halamanChapter 3 Module 4 Lesson 1 Implementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change Processapril ma heyresBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper Chapter I Chapter IiDokumen22 halamanResearch Paper Chapter I Chapter IiDominic BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- ED 205 Module FinalDokumen151 halamanED 205 Module FinalGene Bryan SupapoBelum ada peringkat