Patient Safety

Diunggah oleh

Jesse M. MassieDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Patient Safety

Diunggah oleh

Jesse M. MassieHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Patient Safety: Mindful, Meaningful, and

Fulfilling

STEVEN C. WINOKUR, M.D., AND

KAY J. BEAUREGARD, R. N.

S U MMA R Y Five years after the landmark report of the Institute of Med-

icine To Err Is Human (Kohn, Corrigan, and Donaldson 2000), many are

asking, "Is U.S. healthcare safer?" A number of articles addressing this

question have been written, interviews with nationally recognized patient

safety leaders have been published, and governing boards of many health-

care organizations are examining reports of care provided by their institu-

tions. Robert M. Wachter, writing in the November 2004 issue of Health

Affairs, concludes that, "At this point, I would give our efforts an overall

grade of C-H, with striking areas of progress tempered by clear opportunities

for improvement."

We describe in this article the pursuit of a culture of safety at William

Beaumont H ospital in Royal Oak, Michigan. Our experience has offered us

the opportunity to ponder a number of key questions: H ow does leadership

guide an organization toward a culture of safety? Does culture truly drive

behavior, or is it really the reverse? H ow can a culture of safety be measured

or observed? What levels of resources and commitment are required for

success? Is safety all about systems and processes, or are core values also

involved? What role does the patient play in ensuring safe care? We attempt

to offer guidance, and share lessons learned, for each of these important

questions.

Steven C. Winokur, M.D., is medical di rector of quality i mprovement and chief

patient safety officer and Kay J. Beauregard, R.N., is admi ni strati ve director for

quality, safety, and accreditation at Wi l l i am Beaumont Hospi tal in Royal Oak,

Mi chi gan.

S T E V E N C . W I N O K U R A N D K A Y ) . B E A U R E C A R D I 7

Patient safety cannot he

separated from employee,

visitor, and caregiver

safety.

Steve,

Our industry and our hospital cannot afford

not responding to this study /To Err Is

Human] and making the necessary invest-

ments to assure patient safety. While Beau-

mont Hospital practices many ofthe

recommendations already, w e still make mis-

takes that cost us millions in dollars and

tragedies in human terms. If! had to make

one investment in 2000 it w ould b e in physi-

cian order entry! Thanks for the material b ut I

have a copy o/To Err Is Human on my desk.

Ken

This note was written to Steven

Winokur, M.D., on December 27 of J999

by Kenneth Matzick, executive vice presi-

dent and chief operating officer of Beau-

mont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan.

He wrote in response to a note from Dr.

Winokur one week prior, which provided

him the executive summary

ofthe Institute of Medicine

(IOM) report To Err Is

Human (Kohn, Corrigan,

and Donaldson 2000). Dr.

Winokur had written, "I

would appreciate your thoughts on this,

as many of these recommendations

would require significant commitment

and resources."

At the beginning of 1 999, Beaumont

began a comprehensive one-year review

of its quality management program. A

strong infrastructure of multidisciplinary

peer review and administrative and per-

sonnel support for numerous quality

improvement teams, database manage-

ment, and concerned leadership had been

in place for at least two decades. Acco-

lades were accumulating, such as reviews

received "with commendation" from the

Joint Commission on Accreditation of

Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO),

inclusion in the top-ioo-hospitals lists

and US New s and World Report rankings,

and independent survey best-hospital rat-

ings for the southeast Michigan region.

Yet it was clear to our leadership that a

great deal of work remained to be done to

achieve the level of performance excel-

lence that we feel our patients deserve.

Perhaps what made us somewhat unique

in our ability to respond to the IOM

report was that we were ready to assume

the challenges it presented to all of health-

care: how many hospital executives had a

copy of To Err Is Human on their desk in

December 1 999?

Although we had already pursued and

accomplished many ofthe IOM recom-

mendations, we had not actively nor for-

mally used the term patient safety to

describe our quality management or per-

formance improvement activities. There-

fore, our initial efforts were to define

patient safety; communicate to and edu-

cate our entire organization about patient

safety; and develop an effective, high-

profile infrastructure supported by

updated and yet-to-be-developed patient

safety policies. One of our very first steps

was a presentation to our Board of Direc-

tors about the IOM report in early

2000what it meant and where we

stood. In rapid sequence came our Patient

Safety Vision, a Corporate Performance

Improvement and Patient Safety Plan, the

Corporate Patient Safety Council and

Patient Safety Cabinet, and the appoint-

ment of a Chief Patient Safety Officer at

each of our two hospital divisions.

THE ESSENCE OF PATIENT SAFETY

what is patient safety all about, and how

can an organization be transformed

toward its pursuit?

l 8 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 . ' 1

Human factors, high-reliability orga-

nization, error, injury, disclosure,

empowerment, communication, team-

work, hierarchy, just culture, nonpuni-

tive culture, nurse-to-patient ratios, duty

hours, work shifts, mindfulness, legibil-

ity, computerized order entry, IHI,

NPSF, ISMP. ECRI, JCAHO, CMS,

AHRQ, NQF,' the Leapfrog Group, sim-

ulation, learning organization, standard-

ization, simplification. Six Sigma, lean

thinking, fiow, throughput, handoffs.

Internal Bleeding,'' "The Bell Curve,"' pay

for performance, compensation, litiga-

tion, risk management, organizational

ethics, mission, apology, latent errors,

active errors, Swiss cheese, sentinel

events, incident reports, Codman award,

Eisenberg award. Quest for Quality

award, and on and on; With all of these

terms, do we really understand the

essence of patient safety? At Beaumont,

we believe that we do.

The words of former U.S. Secretary of

the Treasury Paul H. O'Neill, in his

remarks to the National Academy of Pub-

lic Administration's Strategic Human

Resources Conference at the University

of Maryland in September 2002, refiect

our sentiments eloquently;

In a truly great organization, every person

can answer "yes" to the following three

questions:

First, "[A]re you treated with dignity

and respect every day by everyone?"

Second, "Do you have the tools to

make a contribution to your organization

that gives meaning to your life?"

And third, "Does someone recognize

the contributions you make?"

We must strive toward that ideal in

public service. When government employ-

ees can answer "yes" to these questions.

they are in a position to achieve their

potential on the job, and in their lives.

Let me give you an example of how I

have approached the first question, of

treating people with dignity and respect.

When I became the CEO of Alcoa, my first

priority was to improve safety for all our

55,000 employees. Not just improve itI

wanted to make it perfect. I didn't have a

profit calculation in mind1 just knew it

was the right thing to do. Workplace safety

is a key element of treating people with

dignity and respect.

At its very core, patient safety is about

dignity and respect and cannot be sepa-

rated from employee, visitor, and care-

giver safety. Safety is safety. Period.

Consider the "straightforward" issue

of handwriting legibility. If we were to

view legible handwriting as indicative of

our dignity and respect toward others,

would hospitals be able to tackle this

problem today, rather than waiting for

technologies to mature and allow for uni-

versal electronic health records? In other

words, if we considered that an illegible

order to another caregiver is one that

could compromise his or her ability to

properly treat a patient on our behalf,

that we have placed both the caregiver

and patient at risk, could we correct this

problem now? We believe that the

answer is yes.

Leadership at AM Levels

At Beaumont Hospital, we have actively

engaged leaders, managers, and care-

givers at all levels ofthe organization to

join in the pursuit of safety in all areas.

In many cases, leadership for the pursuit

of safety has emerged simply by encour-

aging and empowering our staff. Our

leadership for safety does not just come

m

H

C

m

S T E V E N C . W I N O K U R A N D K A Y J . B E A U R E G A R D I 9

Will y o u kno w a

culture of safety when

you see it?

from the chief executive officer (CEO)

and other executives; it truly comes from

many managers and frontline staff as

well. We have provided tools and oppor-

tunities that allow every person in our

organization the chance to make a contri-

bution that is meaningful to them and

results in a safer environment for all.

Resources and Education

Ofcourse, resources and expertise are

also required to ensure a safe environ-

ment. The desire to create a culture of

safety is not in itself sufficient. Here

again we have witnessed an incredible

amount of activity. Beaumont University

is our hospital's center for edu-

cational programs, which is

intended to support leadership

and management development

as well as staff education. Our

chief learning officer worked closely with

the authors to develop basic performance

improvement and patient safety educa-

tional programs in 2000. As our organi-

zation has evolved toward a culture of

safety, we are seeing educational pro-

grams about safety arise from a variety of

interested departments, teams, and

impassioned individuals. Self-learning is

in abundance, with well more than a core

nucleus of our staff as well as several

physicians showing interest in state-of-

the-art methods such as Six Sigma and

human factors engineering. Similarly,

safety is prominent in all budgetary and

resource allocation decisions.

CULTURE OF SAFETY

Will you know a culture of safety when

you see it? Will you sense something

markedly different about the environment

and the interactions ofthe people? Does

culture change all at once, or gradually?

Observable Behaviors

Our experience indicates that a culture of

safety is demonstrated by observable

behaviors. It can be heard, seen, and intu-

ited day in and day out. We confirm a cul-

ture of safety by observing behaviors such

as the following:

Physicians compassionately disclosing

and discussing errors with patients

Managers genuinely thanking staff for

reporting errors

Nurses routinely repeating back verbal

medication orders

Educators training teams using a

human simulator

Patient transporters checking identifi-

cation wristbands before taking a

patient to a scheduled exam

Receptionists and clerks asking each

patient to affirmatively state his or her

name rather than accepting a passive

nod of agreement

- Staff using standardized communica-

tion techniques when a patient is

handed off from one care setting to

another

Staff ascertaining that the oxygen in

the portable tank is adequate for a

round trip to an ancillary department,

using checklists and guides developed

by our clinical engineers

These are merely a few ofthe behav-

iors that we see throughout our large,

complex organization each and every

day; they are telltale signs of our safety

culture.

Behaviors of administrative- and man-

agement-level staff such as the following

also affirm Beaumont's culture of safety:

Our multidisciplinary root cause

analysis teams seek patient and family

2 0 F R O N T I E R S O FH E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : 1

input to ensure full understanding of

errors that have occurred.

Our established patient care commit-

tees discuss patient safety at each and

every meeting.

Our financial leaders support a dedi-

cated budget source for immediate

remediation of safety issues.

Human factors analysis is routinely

applied to equipment design and

process improvement.

Ad hoc groups throughout our organi-

zation emergeseemingly on their

ownto discuss patient safety oppor-

tunities and solve problems.

One current example of our multidisci-

plinary, state-of the-art approach to real-

world patient safety opportunities

involves analysis of best practice in

telemetry monitoring. We are taking steps

to optimize communication between our

central telemetry monitors and our

nurses at the bedside. We are also

engaged in human factors research

whereby our clinical engineers measure

responsiveness of technicians following

8- and 12-hour shifts through the use of

simulation and gaming techniques. When

completed, our research may well result

in improved telemetry monitoring prod-

ucts, as well as improved processes within

our hospital.

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT

Our organizational leadership demon-

strates that patient safety is a top priority

by communicating this to employees and

medical staff at all levels. They actively

recruit staff and physicians for participa-

tion on patient safety committees and

provide staff, physicians, and manage-

ment the opportunity to enroll in a com-

prehensive series of educational classes

and seminars about the science and prac-

tice of safety. Department manager and

supervisor meetings serve as great oppor-

tunities to communicate about ongoing

patient safety initiatives, increase their

visibility, and establish management's

expectations of staff.

Hardwired for Safety

A great many initiatives and programs

are in place up and down the organiza-

tion to fully institutionalize the culture

of safety at Beaumont. Full involvement

of our physicians, nurses, staff, and

patients and their families is integral to

the success of our program. Stakehold-

ers are actively involved through educa-

tion, including shared feedback from

surveys, hotlines and process owner

reports, involvement in patient safety

work groups, and a supportive environ-

ment for those interested in their own

professional grovi^h in this field. Medical

chiefs routinely dedicate agenda time to

patient safety at medical staff depart-

ment meetings. Appointed patient safety

leaders visit every clinical department

and ambulatory site at least annually to

conduct executive rounds. Managers are

expected to discuss patient safety at staff

meetings and as part of in-service train-

ing. Patient safety educational tool kits

with sample agendas, video vignettes,

and case studies have been made avail-

able to all managers.

Readily Available Documents and

Literature

All medical staff and hospital employees

can readily access an abundance of

patient safety information through the

internal web site that contains resources

such as our Patient Safety Vision, our

Corporate Performance Improvement

H

C

m

S T E V E N C,W I N O K U R AND K A Y j . B E A U R E C A R D 21

and Patient Safety Plan, many relevant

patient safety pohcies, and a long list of

internal patient safety expert contacts

and external reference web sites. Our

intranet allows for simplified enrollment

for numerous patient safety courses, as

well as access to printed course materi-

als. Frequent articles pertaining to

patient safety are published in the

employee, physician, and management

newsletters. If one has any doubt as to

the maturity of our evolving safety cul-

ture, just imagine reading about such

topics as situation awareness in our hos-

pital newsletters.

INFRASTRUCTURE

The culture of safety is diffused through-

out all sites and integrated through the

system through a variety of pathways.

. , - Failure mode and effects

Encourasine patient safety , ^ j . ,

** ** '^ ' ' analyses are studied by

Storytelling is effective in

promoting candid group

dis cus s ion.

groups with broad repre-

sentation from a variety of

disciplines and hospital

units. Intensive assess-

ments or sentinel event recommenda-

tions are shared across the organization

so that the lessons learned may be

applied in all departments with similar

risk environments. Variance reports from

all organizational settings, both inpatient

and ambulatory, are aggregated and ana-

lyzed in one centralized patient safety

database.

At the onset of our organizationwide

education plan, all administrators, man-

agers, and medical staff leaders attended

a three-hour patient safety overview

course offered through Beaumont Uni-

versity. Subsequently, new managers are

expected to take this course as a core lead-

ership requirement. New employees are

introduced to patient safety goals at their

initial orientation. Similarly, newly

appointed physicians are introduced to

our patient safety program at the time of

their acceptance to the medical staff.

These educational programs and require-

ments ensure a consistent level of patient

safety education for all caregivers

throughout the organization. Our

brochure "First, Do No Harm: A Guide to

Patient Safety for Beaumont Employees"

is provided to all employees to facilitate

learning and discussion of patient safety

(Exhibit I, pages 29-30).

REPORTING AND FEEDBACK

Potential safety concerns are identified

through various data collection sources:

executive patient safety rounds; patient,

employee, and medical staff surveys; risk

management cases; root cause analyses;

variance/sentinel event reports; anony-

mous employee or patient reports via an

internal hotline (i-SAFE); and informal

communications at manager meetings,

among other avenues.

A supportive environment for error

reporting is demonstrated by the way that

we respond when errors are reported.

Process owners (designated recipients of

variance reports) send thank you notes to

individuals who submit reports. An

excerpt from a recent note sent by our

medical equipment process owner illus-

trates this nicely.

Vicki,

Glad to hear n o on e w as hurt. I ' ll look f or-

w ard to s eein g the varian ce. Y ou are probably

already aw are, but let me take the opportu-

n ity to rein f orce the n on pun itive n ature of

varian ces an d the dedication Beaumon t

exhibits to quality. Som,e of our bes t quality

w ork has res ulted f rom in comin g varian ce

2 2 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : 1

reports. We'll look forward to working together

on root causes and potential quality improve-

ments.

Regards,

Steve

Recognition programs, such as WOW

cards (redeemable for Si.oo at our gift

shop, coffee shop, and cafeteria), are

given to staff who enthusiastically partici-

pate in patient safety rounds. Beaumont's

Corrective Action Policy recognizes the

inevitability of human error and the need

for managers to avoid inappropriate puni-

tive responses to errors. The human

resources department provides education

and support to managers to ensure that

this policy is carried out as intended. A

customized checklist is used to make cer-

tain that evaluation of employee errors is

performed from a process-focused per-

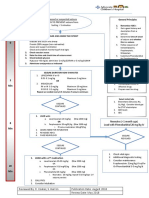

spective (Figure i).

Support services are available to all

employees and medical staff who may

need assistance to overcome feelings of

grief, frustration, anger, embarrassment,

guilt, or loss of confidence that may occur

as a result of clinical error. Encouraging

patient safety storytelling is effective in

promoting candid group discussions.

Staff who see a supportive environment

and learn about genuine process

improvement as a result oftheir reports

continue to report and encourage others

to do so as well.

Measurement of patient safety

progress is accomplished through a vari-

ety of mechanisms. Direct feedback to

senior leadership is encouraged, from

frontline care providers, support staff,

and patients themselves. Employee and

FI GURE 1. Checklistfor Evaluating staff Errors

Objective Review: When reviewing a situation to determine if action should be taken, recog-

nize that human error may occur. Review the procedures, processes, and equipment

involved in the error to determine if the error is process or procedure related. It is important

to remove personal emotions and biases from consideration and use sound, logical thinking

when determining the course of action to take.

What is your process or procedure?

How was staffing that day?

- Were there any unusual circumstances or events that happened that day?

Was the employee performing within the scope of his or her position?

Does the employee have the necessary tools and equipment to effectively perform his or

her job?

Did the employee make a mistake?

Have the procedures and/or protocols been clearly communicated?

What does the employee's performance history or work record look like?

How frequently does the employee make errors?

What was the impact ofthe error?

What is the error rate of this procedure?

m

H

C

S T E V E N C . W I N O K U R A N D K A Y J . B E A U R E G A R D 2 3

A just culture had

become a way of life at

our hospital.

physician surveys assess patient safety

culture, teamwork and communication,

willingness to reports errors, adequacy of

education, and leadership responsiveness

to identified patient safety risks. Areas for

improvement are prioritized

and championed by key lead-

ers in the organization.

Progress is tracked through

the hospital's performance

improvement steering committee, com-

posed of senior hospital and medical staff

leaders. Well-defined patient safety met-

rics are reported monthly to the CEO and

board of directors.

ANALYSI S OF DATA

Analyses of data from variance reports,

process owner reports, patient safety

rounds, sentinel event reports, i-SAFE

hotline calls, patient safety surveys, risk

management cases, and patient feedback

are used to prioritize patient safety initia-

tives.

An innovative approach to analyzing

key processes is illustrated by our variance

reporting methodology. At the onset ofthe

reengineering of our variance reporting

process, common process issues were

identified by an analysis of historical hos-

pital variance report data. Once the key

processes of interestpatient falls, med-

ication events, equipment events, and so

forthwere determined, a process owner

was recruited for each key process. A

management engineer, administrator, and

physician champion were identified to

support each process owner, thus develop-

ing process owner teams. A standardized

method allows all process owners to

assess, track, and analyze the data in a

similar fashion. The analysis strives to

identify root cause process issues that

may include the following:

Patient identification

Staffing levels

Availability of information

Physical environment

Patient assessment

Equipment-related processes

Orientation and training of staff

Communication among caregivers

Data from all process owner reports

are aggregated each calendar quarter so

that both individual processes and the

overall organizational process can be ana-

lyzed and serve as teaching aides.

TI PPI NG POI NT

An error occurred at Beaumont. Correc-

tive (disciplinary) action was being consid-

ered for several staff members who had

been involved in the error. During the

case review session, the incident was

determined to have resulted from a sys-

tem failure and not from an individual

performance issue. Over a long period of

time, safety practices in the failed system

had eroded, and the procedures that

resulted from that erosion became accept-

able in the hospital culture. Written proce-

dures had not been followed for some

timeemployee "work-arounds" pre-

vailed. Nothing bad had happened until

this incident. The employees involved in

this event were "good, conscientious,

long-term" employees. Were they at fault?

Or was our culture at the time the real

basis for this event?

Our analysis: If these employees were

at fault, then the educator who trained

them was at fault; their peers who vali-

dated the process by acting in the same

manner each day were at fault; and their

manager, their director, their administra-

tor, and the people writing this article

were all at fault for allowing this process

2 4 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : 1

to break down. These good, conscientious,

long-term employees were part of a faulty

process and part of a culture that did not

adequately emphasize safety.

The use of corrective action to disci-

pline these employees was determined to

be unnecessary. This decision proved to

be an excellent educational case study, as

staff witnessed firsthand the leadership's

commitment to sound patient safety prin-

ciples. The grapevine is not to be underes-

timated. As a resuh of this case, the

informal communication network worked

at a rapid pace. Nearly all management

staff, and many employees, quickly

learned that there was a new approach to

patient safety; a just culture had become a

way of life at our hospital.

PUTTING THE "PATIENT" IN

PATIENT SAFETY

Organizations that proactively teach

patients how to be partners in safety have

a win-win situation. However, it is essen-

tial to create a culture of patient safety

within the organization prior to assuming

that staff will embrace patients as partners

in care. Staff must be equipped with the

appropriate skills and practice in a sup-

portive culture before they will readily

accept the concept of including the patient

as a partner in care. Beaumont's strate-

gies to "put the patient in patient safety"

include the following:

Design of all patient educational mate-

rials with an emphasis on patient

safety

Patient interviews by senior leadership

during executive safety rounds

Inclusion of patient safety topics in

community education classes

Encouragement for employees to seek

new opportunities to involve patients

Fundamental to our efforts to involve

our patients and their family members is

our "Partners in Safety" brochure (Exhibit

2 , pages 31-32 ). This brochure is provided

to every inpatient and every surgical

patient and is made readily available in all

ambulatory settings. We also actively seek

opportunities to involve patients and their

families in several key processes of care,

such as the following:

The patient identification process

The handoff/transfer process

The surgical site-marking process

The prevention of infant abduction

The medication administration

process

Infection control

The success of these strategies has

been measured through specific ques-

tions on the Patient Safety Department

Assessment tool completed by manage-

ment staff We are pursuing several addi-

tional strategies to further involve the

patient in safety. These include a patient

orientation video and online educational

tools and reference web sites.

GENUINE CHANGE

oft he many examples of genuine change

toward patient safety that we have seen, a

few highlights are featured here.

Patient Identification

Improvement of our patient identification

process was one of our most important

initial goals. Numerous interventions and

process changes were made to allow us to

come as close to perfection as possible in

this critically important step. We stan-

dardized our approach to patient identifi-

cation across the organization, including

standardization ofthe wristbands, adding

m

S T E V E N C. W I N O K U R AND K AY J . B E A U R E C A R D 2 5

Waiting for ne w

te chnologie s and not

addre ssingflaw s in

curre ntly w ritte n

me dication orde rs is not

acce ptable in our culture .

forcing functions'* and point-of-care

reminders, and working with vendors and

suppliers to improve some ofthe related

patient identification products. Bar code

technologies were introduced to meet

selected needs. A consistent role for the

patient is included as part ofthe multi-

check system.

The impact of these process changes

has been dramatic, as evidenced by the

data from Beaumont's variance report

database, which shows that the number

of incidents related to patient identifica-

tion has fallen sharply. We have cele-

brated this success with our employees

through internal recognition programs.

Medication Safety

Our medication safety processes have

been similarly strengthened. Fundamen-

tal to achieving optimal outcomes for our

patients is providing medications in a

safe manner. Opportuni-

ties for improvement are

learned from internal data

sources as well as ongoing

review of recommenda-

tions from outside experts

such as the Institute for

Safe Medication Practices

and JCAHO's Sentinel

Event Alerts. The comprehensive Medica-

tion Process Safety Plan, with 28 short-

term and 19 long-term action items, was

developed. A targeted intervention,

known as "Make It Complete," is directed

at improvement ofthe written medica-

tion order.

Writing a medication order clearly

and completely is a critical first step in a

genuinely safe medication process.

Although we are pursuing technologies

such as computerized physician order

entry for medications, waiting for these

new technologies and not addressing

flaws in currently written medication

orders is not acceptable in our culture.

Therefore, specific guidelines for writing

medication orders were approved, and an

educational campaign ensued. Medica-

tions would not be dispensed by the

pharmacy or administered by the nurse

until the order was "complete" according

to these guidelines. "Make It Complete"

resulted in measured improvement in

prescriber identification, order legibility,

and avoidance of prohibited abbrevia-

tions.

Information Transfer During Patient

Handoffs

Another example of Beaumont's

improvement efforts is information

transfer during the patient handoff

process, which is prioritized as a current

hospitalwide improvement goal. A hand-

off is defined as the transfer of responsi-

bility for a patient from one staff member

to another or from one unit to another.

Expectations at the time of transfer of

care include the following:

It is verified that that patient is appro-

priately prepared for a procedure in an

ancillary department.

Oxygen and other necessities are avail-

able during transport and upon

interim designation.

Receiving staff are provided clinical

information when and where they

need it (not buried in computer

screens or in an unfamiliar portion of

the paper record).

Ancillary staff communicate key infor-

mation back to unit staff (e.g., any

unexpected reactions, the need for

rapid assessment upon return to the

unit).

2 6 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : 1

FI GURE 2. Safety Rounds Sample Agenda

"First, Do No Harm" brochure

"Partners in Safety" brochure

Sentinel event process changes

Site and sidedness process

Patient handoff process

Clinical alarms

Medication safety

Review of physical environment for hazards

Principles of patient safety

Near-miss and error reporting process

Patient identification

Final verification process

Hand hygiene

Chemotherapy administration

Infant/child security

A person-to-person verbal exchange of

information takes place.

Patients participate in the process.

Use of these improvement strategies is

clearly visible, and they are currently

being evaluated by our organization.

SUSTAINING THE EFFORT

Patient safety rounds are regularly held in

all ambulatory and inpatient clinical

departments (see Figure 2 for a sample

agenda). Rounds are attended by the chief

patient safety officer, the hospital safety

officer, an infection control practitioner,

the environmental safety coordinator, a

clinical engineer, selected management

engineers, a human factors specialist,

departmental leadership, and available

unit/department staff.

Goals of patient safety rounds include

advancement of our safety culture and

continued identification of areas of risk so

that risk reduction strategies may be put

in place. Fire safety, environmental safety

or hazardous chemical risks, equipment

safety, employee health and safety, and

infection control procedures are all

assessed during these rounds. Patient

safety rounds provide the opportunity for

visible, active participation by hospital and

medical staff leaders and provide a forum

for staff to discuss their concerns directly

with leadership.

CONCLUSION

For each hospital to tackle patient safety

efforts on its own is itself a genuine bar-

rier to safe systems. We suggest partici-

pating in collaborative efforts and sharing

best practices with other organizations.

Such collaboration is important to the

success of patient safety efforts of large,

complex systems and can be critical for

smaller hospitals that do not have execu-

tive and leadership staff dedicated solely

or even partially to patient safety roles.

For Beaumont, our observations dur-

ing patient safety rounds are perhaps the

most telling signs of our evolution

toward a culture of safety. Departments

now welcome the opportunity to show-

case the improvements in safety that they

have made. Department managers and

staff are the drivers ofthe conversation

during our visits. Observable patient

safety behaviors have permeated our

organization. We believe that our appeal

to core values of dignity and respect has

motivated our staff to modify these

behaviors, thus moving us toward a safe

culture.

m

S T E V E N C . W I N O K U R AN D K A Y J . B E A U R E C A R D 2 J

NOTES

1. Institute for Healthcare Improvement

(IHI); National Patient Safety Founda-

tion (NPSF); Institute for Safe Medica-

tion Practices (ISMP); FCRl (formerly

the Emergency Care Research Institute);

Joint Commission on Accreditation of

Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO);

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Ser-

vices (CMS); Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality (AHRQ); National

Quaiity Forum (NQF)

2 . See Wachter and Shojana (2 004).

3 . See Gawande (2 004).

4. Forcing functions are steps in a process

that must be completed in order for the

next step to occur. For example, you

must have your foot on the brake to

move the transmission in your car from

park to reverse; in an airplane bathroom,

you must lock the door to turn on the

light. Forcing functions are very impor-

tant for safety system design.

REFERENCES

Gawande, A. 2 004. "The Bell Curve." [Online arti-

cle created 12 /6/04; retrieved 5/4/05.] New

Yorker, http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content

/?04i2 o6fa_fact.

Kohn, L. T, }. M. Corrigan, and M. S. Donaldson

(eds.). 2 000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer

Health System. Washington, DC: National Acad-

emies Press.

O'Neill, P. H. 2 002 . "Treasury Secretary Paul H.

O'Neill Remarks to the National Academy of

Public Administration Strategic Human

Resources Conference University of Maryland."

[Online article; retrieved 4/2 7/05.] September

10. http://www.treas.gov/press/releases

Wachter, R. M. 2 004. "The End ofthe Beginning:

Patient Safety Five Years After To Err Is

Human'." [Online article created ri/3 0/04;

retrieved 5/4/05.] Health Affairs Web Exclusive.

November 3 0. http://content.healthafFairs.org

/cgi/reprint/hlthaiT.W4.554vi?maxtoshow=&

HITS-io&hits-io&RESULTFORMAT=&

authori=wachter&fulltext=to+err&andorex

&stored_search-&F IRSTIN D EX=o&

resourcetype=i&journalcode =healthafT.

Wachter, R. M., and K. Shojana. 2 004. Internal

Bleeding: The Truth Behind America's Terrifying

Epidemic of Medical Mistakes. New York: Rugged

Land. LLC.

2 8 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : i

I

I-I

)-<

o

PQ

nj

cx

en

O

X

C

o

CQ

m

X

X

a "

11

till

or. ?:

c ^

til

i i

c

rt

3

c

rt

I

-5

f

i

r

s

t

c

t

i

rt

S

I

X

V

"rt

c

E

\--f

c

E'

g

rt"

1

1

=;

S

1

s

_ i-

rt

^*;

" ^

1

3

~?

)^

g

a

t

i

<

=

l

i

s

s

i

o

n

t

1

"a

rt

1

2

i

- -a s ^

II

c c = -=

= = 5 0

i: H S

5

II

s '^

-:;

^ s

b 5

11 i. 2 1

Cf .5 3

o = ^

^ - -q -^

S 1^ -S ^ ^ i

^p- s ^ u h

SI

ex _ .ii c .s

m

H

m

S T E V E N C . W I N O K U R A N D K A Y j . B E A U R E C A R D 2 9

>

CO

t/3

O

X

4 - '

c

o

s

CQ

S

rt

H

CD

X

X

2 =

B. e

O IP

c

a.

ic

e

-a

rt

c

o

'

s *

1 ^ ^

E - - S " S.

I I

5 E

- p 51 C

"= rt 3

71 - - - * .E e

rt = _g 3

iil

-a . I

^ 1

.J, ij

E rt i

- -j2 ^ i

0) g

. - ^ 7 5

H - ^ =f^-g

S = ~ -E

- -3

-.r, i . . rt

C fe 1-

Z: a.-5

I

III

i

^ rt ^

"i"^ -s

& - . : : :

?: s M ^

3

1

111 i

, q j . s _

. 6 . ac

- i; s i

' -a M o o .2

J 3 i-^ 3 = c

i^ i - S rt S ^

"I I 1= rt . ^ 1

I e I i 11 i

Q-.g^ ^ c 2 =p -^

ts

11

il

I!

i

c

g-i

1 i _

g E 'S^

-a _o ^

"S - - S

1

i

* s

3 l ^

w f^ 11

ill

i 2 ^

'a, .3; =

-C rt rr

^

3 0 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : i

c

I-I

3

u

O

03

in

O

X

ill

o

re

PQ

PM

ffi

X

X

q -9- C

Ji-a; - =

.

"

n

g

rt

i n

c

a

r

e

b

e

a

l

t

a

k

i

i

r

s

e

s

.

3

C

m

c

a.

rt

"u

c

h

n

i

i

s

t

s

,

1

u

rt

^.

1

.S" ui U

0 "3 o 3

fv 0 -1 " ^

rt C ^ -

c/1 O i-T ^

i

f

e

t

y

:

e

a

u

r

r

a

t

i

e

r

:

a

l

r

o

iA CQ CL. =

. -s -s J

-d

c

n

:

t

i

v

e

C rt

rt CL

J

CH ^5 < "O H -Q " .

c

- 1

rt " ^

y qj

y

o

"1

rt

d

t

o

r

1

8

_c:

c

?^

h

a

t

e

1

u

&.

"3

l

e

d

i

c

i

p

l

e

x

E

n

a

n

y

c

o

U l

3

1 3

,0 P

U2 >- ,

rt dj

^ ^

c

^ i

* " * uf

(J U

> X

s

p

r

c

o

u

e

n

t

.

r

e

g

i

c

a

r

a

u

r

u 0 CQ

m

H

m

S T E V E N C. W I N O K U R A N D K A Y | . B E A U R E C A R D 3 I

.Si.

o

a.

o

X

c

o

CQ

CD

I

X

rt

3

o

r

i

f

u

o

-a

O

n

u

r

s

e

i

\

l

y

o

u

r

^ 5

3

l

u

t

y

o

- a

^

3

O

> .

u

L U

i

o

n

s

d

e

c

i

s

i

CO

B

e

a

p

a

r

t

o

f

a

r

e

o

u

y

o

u

r

:

a

b

o

u

t

l

e

s

c

i

o

n

s

- i

^ ^

a

l

t

e

s

a

d

i

c

E

^

l

o

s

i

s

,

E

m

e

n

t

CD

09

a

b

o

u

t

y

o

u

r

t

i

r

e

r

i

g

CT"

E

c

i

n

g

d

o

t

S

o

u

r

>-

-a

CD

C

' ^

CO

^

CD

>

^

y

o

u

r

m

e

a

b

o

u

t

c

o

S

h

a

r

e

a

l

l

i

n

f

o

r

m

;

e

c

t

Cu

rt

y

o

u

i

l

u

r

g

e

r

t

a

v

i

n

g

s

y

o

u

'

r

e

I

"

CO

1

* -

t

r

e

. ^

n

e

e

d

s

w

p

e

c

i

a

l

c'

c

o

n

d

i

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

a

~ rt l

E

l

J.J 3 - -

:

h

e

a

i

t

h

y

o

b

o

u

t

^ > "^

c o "

;

e

o

n

t

o

r

a

t

e

d

i

i

1

f

r

e

e

t

OJJ "_l J-

^. OJ

,_ Oj u-

3 ^ S

3 >

.:= rt

b

o

u

t

l

u

r

s

e

.

rt ^

r- !-

C "

U.

rt

I-. ^

.3 -a

'^ P

A

s

k

f

r

o

t

1-1

3

i

b

o

u

t

V

O

e

c

a

i

l

s

;

i

-o

y

o

u

r

c

a

r

e

g

i

v

e

r

s

.

B

e

s

u

r

e

'

t

o

p

r

o

v

i

o

o

g

r

a

m

s

>

2

rt

u

d

^ 3

C

1

n

e

s

s

e

s

a

h

a

s

i

l

l

m

e

d

i

c

a

l

h

i

s

t

o

r

y

J

1

c

1

n

e

s

s

c

a

:

rt

f

b

s

i

t

e

s

_g

rt

C

0

f

o

r

m

a

.B

3

I

t

o

m

s

y

o

>

l

a

.

o

p

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

s

,

a

s

w

-c

i -

n

o

t

V

p

:

e

r

s

d

:

e

w

o

r

k

rt

J=

"rt

JZ

o

s

u

p

c

rt

d

P

>^

o

v

e

s

.

Q

h

e

s

y

w

e

a

r

g

l

h

o

t

o

u

t

n

d

s

o

r

i

u

l

e

d

t

h

e

i

y

o

n

e

w

v

e

w

a

s

i

"

5

O

1

t

h

a

t

y

l

a

t

i

o

r

c

E

rt

d

1>

j ^

I

..<

L

i

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

o-

Ti

3

O

l

'

l

e

a

s

e

t

e

l

l

u

s

i

r

'

rt

_C

C

?

--3

C

u!

i2

p

U

i

u

c

h

a

s

\

c

a

r

e

,

:

k-

3

c

o

n

c

e

r

n

s

a

b

o

u

t

t

o

u

s

e

h

o

w

1

_5

Q

s

u

r

e

y

i

-a

r

f

o

r

m

t

u

a.

3

O

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

n

e

d

i

t

/

h

a

t

r

1

as

g

c

a

r

e

a

i

-

y

o

u

r

--^

l

e

n

t

n

c

1 -H

e

q

u

l

o

n

e

.

oo

t

e

s

t

I

S

g

o

i

n

g

t

o

\

s

o

m

e

t

h

i

n

g

i

s

b

e

i

n

g

a

n

e

t

a

k

i

CO

)

s

p

i

t

a

o

>

j

u

l

e

a

> .

U l

u

rt

I

3

o

M

a

k

e

s

u

r

e

t

h

a

t

y

l

E

l

]

5

OJ

-

q

u

e

s

n

o

i

v

e

.

A

s

i

<

B

m

a

t

i

o

n

t

h

a

t

y

o

u

i

r

r

y

a

l

i

:

c

a

r

e

t

h

e

o

e

i

t

t

e

m

cy

> i

CD

;

e

d

.

' 4 . '

^\

m

a

n

y

t

i

m

e

s

a

s

v

(

rt

IU

:^ 2

rt --

3 1

H

i

n

t

;

s

u

p

p

i

E -

-

! ' E

d)

e

.

03

u

r

e

r

e

CO

y

o

u

Q

m

e

m

b

e

r

a

m

i

l

y

OJj

I

f

p

o

s

s

i

h

i

e

,

b

r

i

n

c

o

.

a

t

i

i

c

I

s

i

n

f

o

r

e

r

d

r

u

g

c

o

-a

1

t

o

i

n

t

u

%

L -

rt

h

e

a

l

t

CL,

X

e

e

l

3

h

e

i

p

y

o

'

S

V

c

a

n

_(=

f

r

i

e

n

d

w

i

t

h

y

o

u

"oJj

Ul

rt

Ul

t

t

o

y

o

i

1

p

o

r

t

a

n

1

-

r

v

o

u

r

.'

e

n

t

e

JZ

it

---

I

v

e

s

w

t

h

e

i

b

e

r

d

h

e

i

p

n

m

o

r

e

c

o

n

i

f

o

r

t

a

b

l

>.

crt

3

O

i

rt

n

u

r

s

e

s

.

a

n

d

d

o

c

t

o

r

s

t

l

y

o

u

r

7 1.'

I

b

a

d

e

t

B

rt

.Is

o

r

t

h

e

"^

-^

l

.

o

c

c

o

i

n

s

t

r

u

c

t

i

a

v

c

o

r

rt

E

3

O

C

C

3

O

2

n t

r

p

r

o

b

l

i

t-j

o

a

e

r

g

t

e

s

,

s

a

rt

aJ

B

-r-i

rt

3

rt

Q-

; ^

t

i

o

n

s

i

r

e

d

i

c

a

w

i

t

h

m

v

e

h

a

d

rt

c

r^

"-*

u

t

w

r

i

i

L

v

e

y

o

^ ~

>

"O

rt

rt

T3

b

i

r

t

3

O

o

n

e

o

f

t

o

c

a

l

i

a

Y

o

u

'

r

e

a

l

s

o

w

e

l

c

i

e

n

c

i

n

g

.

r

x

p

e

r

i

r

e

n

t

l

y

e

a

r

e

c

u

r

p

JZ

H

>^

o

u

r

s

t

a

i

n

g

y

3

e

k

e

d

(

-C

u

9

at

c

u

s

t

o

m

e

r

h

o

t

l

i

n

i

ri

2

h

F

e

e

l

f

r

i

o

n

s

.

r

q

u

e

s

t

e

e

x

p

e

c

rt

O

U

a

r

e

o

r3

u

-0

I

p

U

S

i

5b

c

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

i

l

y

a

m

e

^

:

c

a

r

e

.

^ :3

w

i

l

l

O

>.

:5

2

4

8

-

5

5

1

-

2

2

7

3

i

p

r

o

'

r

o

y

)

r~

2

4

8

-

9

6

4

-

8

8

0

8

i

_:

^ ,

o

l

u

s

u

a

l

1

U i

f

F

e

r

e

n

t

l

o

o

k

s

d

i

c

k

s

-C

3

C

t

o

r

c

-a

Uf

p

3

u.

l

u

r

e

y

(

q j

^ r-

1J r~

r\ C

Qj r^

i

r

n

a

m

i

n

o

r

t

r

e

C

S

y

o

t

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

rt ^

u. C

0 >.

~o 5

r

i

s

t

b

a

s

t

e

r

i

n

g

> 'E

u. -

3 E

O T3

>. rt

3 2 F R O N T I E R S O F H E A L T H S E R V I C E S M A N A G E M E N T 2 2 : 1

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Identifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportDokumen11 halamanIdentifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportDokumen10 halamanOral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementDokumen12 halamanEffective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Jpeds Aom 208Dokumen3 halamanJpeds Aom 208Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- i-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLDokumen1 halamani-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDokumen18 halamanOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- IJMEDokumen7 halamanIJMEJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsDokumen8 halamanWhat Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Making The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesDokumen5 halamanMaking The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Cbig Cross-ReportingDokumen25 halamanCbig Cross-ReportingJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceDokumen40 halamanPreventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- dBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGDokumen4 halamandBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Suidi Oklahoma ProviderDokumen28 halamanSuidi Oklahoma ProviderJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Status EpileticusDokumen2 halamanStatus EpileticusJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Male Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Dokumen3 halamanMale Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Noisey PlanetDokumen1 halamanNoisey PlanetJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Minority YouthDokumen28 halamanMinority YouthJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- COVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixDokumen1 halamanCOVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Kinshipguardianship PDFDokumen139 halamanKinshipguardianship PDFJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Dokumen1 halamanIntimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- How Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Dokumen2 halamanHow Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Domestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Dokumen44 halamanDomestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- CDC Capacity BuildingDokumen16 halamanCDC Capacity BuildingJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- How Loud Is Too LoudDokumen2 halamanHow Loud Is Too LoudJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Aap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersDokumen39 halamanAap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- In Drinking Water: Sources of LEADDokumen1 halamanIn Drinking Water: Sources of LEADJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Advancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForDokumen132 halamanAdvancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Fireworks ShowDokumen2 halamanFireworks ShowJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Cbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Dokumen8 halamanCbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Jesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Essentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsDokumen1 halamanEssentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsJesse M. MassieBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- List of 2 Years AffiliationDokumen15 halamanList of 2 Years AffiliationAahad AmeenBelum ada peringkat

- CV of DoctorDokumen1 halamanCV of DoctorBobby Jatt0% (1)

- HEALTHDokumen28 halamanHEALTHKristine SaulerBelum ada peringkat

- NYS Office of Professional Conduct Opens Investigation of Controversial Psychiatrist Kelly Brogan (11/24/20) + My Complaint Re: Her License (3/22/20)Dokumen5 halamanNYS Office of Professional Conduct Opens Investigation of Controversial Psychiatrist Kelly Brogan (11/24/20) + My Complaint Re: Her License (3/22/20)Peter M. Heimlich100% (1)

- HIS-district LaboratoryDokumen6 halamanHIS-district LaboratoryEricka GenoveBelum ada peringkat

- BSN Curriculum 20 21 English 1Dokumen3 halamanBSN Curriculum 20 21 English 1ROSE DIVINAGRACIABelum ada peringkat

- Resume PDFDokumen1 halamanResume PDFapi-353271874Belum ada peringkat

- James Sloan Takes Firm Stand On Issues Important To Tennessee House of Representatives District 63Dokumen4 halamanJames Sloan Takes Firm Stand On Issues Important To Tennessee House of Representatives District 63PR.comBelum ada peringkat

- Experts Validation TableDokumen20 halamanExperts Validation TableDeepti KukretiBelum ada peringkat

- Continuing Competency Log PrintDokumen2 halamanContinuing Competency Log PrintBobBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Applications of Nursing DiagnosisDokumen768 halamanClinical Applications of Nursing DiagnosisAyaz Ahmed Brohi100% (1)

- 6450a6d07795498d Derma360reportDokumen12 halaman6450a6d07795498d Derma360reportNeelam PahujaBelum ada peringkat

- Medical - Strips (Medical Grade vs. "Hospital Grade")Dokumen22 halamanMedical - Strips (Medical Grade vs. "Hospital Grade")Nirav DesaiBelum ada peringkat

- Pharma DirectoryDokumen1.899 halamanPharma DirectoryVandana Tyagi100% (2)

- Changes in Hospital Competitive StrategyDokumen23 halamanChanges in Hospital Competitive Strategyanantomi100% (1)

- Panic Disorder: GuidelineDokumen3 halamanPanic Disorder: Guidelineputri weniBelum ada peringkat

- (Medical Radiology) Lluís Donoso-Bach, Giles W. L. Boland - Quality and Safety in Imaging-Springer International Publishing (2018)Dokumen187 halaman(Medical Radiology) Lluís Donoso-Bach, Giles W. L. Boland - Quality and Safety in Imaging-Springer International Publishing (2018)Piotr JankowskiBelum ada peringkat

- Project Seminar Hospice FedoraDokumen3 halamanProject Seminar Hospice FedoralalithaBelum ada peringkat

- ��تجميعات الفارما�Dokumen4 halaman��تجميعات الفارما�Turky TurkyBelum ada peringkat

- You Are Dangerous To Your Health CRAWFORDDokumen18 halamanYou Are Dangerous To Your Health CRAWFORDGonzalo PaezBelum ada peringkat

- Pola Penggunaan Obat Antihipertensi Pada Pasien Hipertensi: Teti Sutriati Tuloli, Nur Rasdianah, Faradilasandi TahalaDokumen9 halamanPola Penggunaan Obat Antihipertensi Pada Pasien Hipertensi: Teti Sutriati Tuloli, Nur Rasdianah, Faradilasandi TahalaSifa ShopingBelum ada peringkat

- Healthcare & Life Sciences ReviewDokumen47 halamanHealthcare & Life Sciences Reviewmercadia59970% (1)

- Food Handler Training CoursesDokumen2 halamanFood Handler Training CoursesSai Ram ChanduriBelum ada peringkat

- Cv. Dr. Saldy YusufDokumen6 halamanCv. Dr. Saldy YusufMuhammad FaturrahmanBelum ada peringkat

- Physical Education and Health 12Dokumen2 halamanPhysical Education and Health 12Jenia Alexis CapaBelum ada peringkat

- Dental Claim FormDokumen2 halamanDental Claim Formmiranda criggerBelum ada peringkat

- Francois Gremy (Autosaved)Dokumen7 halamanFrancois Gremy (Autosaved)Donya GholamiBelum ada peringkat

- Dental Officer Information - e (1989)Dokumen10 halamanDental Officer Information - e (1989)Marian GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Policies Under NMHC Act 2017Dokumen2 halamanPolicies Under NMHC Act 2017SAKSHI SHRIPAL SHAH 1833474Belum ada peringkat

- James Belgira Tamayo, RMT, MD James Belgira Tamayo, RMT, MDDokumen1 halamanJames Belgira Tamayo, RMT, MD James Belgira Tamayo, RMT, MDfilchibuffBelum ada peringkat