Macroeconomics Questions from 2013 Chinese Economics Exam Analyzed

Diunggah oleh

cankawaabDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Macroeconomics Questions from 2013 Chinese Economics Exam Analyzed

Diunggah oleh

cankawaabHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Macroeconomics Questions

2013 Economics Honors Exam

Question 1. (40 minutes) The savings rates of Chinese households are among the highest in the world.

This question asks you to analyze the consequences and potential causes of high Chinese saving using some

standard macroeconomic models. As you answer the dierent parts of the question, assume that the Chinese

saving rate underwent a large once-and-for all shift upward some time ago (say, around 1978) and that the

saving rate has remained at its high level since then.

a.) For this part of the question, assume that China is a large open economy with perfect capital mobility.

(In reality, China has capital controls, but you can ignore them here.) What is the likely long-run impact

of an increase in the saving rate on the level of Chinese investment, net exports, real interest rate, and real

exchange rate? Assume that the savings rate occurs because of a level shift in the consumption function;

the marginal propensity to consume MPC, which is greater than zero and less than one, does not change.

To get full credit, use a graph (or graphs) to bolster your argument. (Note: this part of the question asks

about the long run, in which prices are perfectly exible but the level of capital and labor are xed at K

and L, respectively. In the very long run, investment I is allowed to change the capital stock K. But thats

not what we are dealing with here.)

Answer: In a closed economy, a higher savings rate lowers the real interest rate r and raises investment

I. In a small open economy, an increase in the savings rate lowers the real exchange rate and increases

net exports NX. The large open economy case is somewhere between these two polar cases: r is lower, I

is higher, is lower, and NX is higher. To get partial credit, students can simply describe the polar cases

and say that the large open economy is somewhere between these polar cases. To get more points, they

should mention the role of capital ows in this answer: Lower interest rates in China (lower r) increase net

capital outows and therefore lower the real exchange rate. This increases net exports. To get full credit,

students should show how this works using the standard three-panel graph for the large open economy. I

have attached a PDF of this three-panel graph that depicts a REDUCTION in savings. The students should

draw something similar, but with savings going up rather than down.

b.) Now think about the eect of higher savings in the very long run. What will happen to the levels of

aggregate output Y and output-per-worker

Y

L

as a consequence of the increase in the saving rate? Be sure

to discuss what will happen to Y and

Y

L

during the immediate period after the savings increase as well as

the permanent eects of the savings increase. In this part of the question and in all following parts, assume

that China is a closed economy. Use graphs.

Answer: This is a plain-vanilla Solow model question. The once-and-for-all increase in the saving rate

s raises the steady-state level of k for the Chinese economy. As China transitions to this new steady state,

output-per-worker grows at a higher-than-steady-state rate (which is g). The ultimate eect of the higher

savings rate on

Y

L

is to raise its level; when China reaches the new steady state, the rate of growth in output

per worker reverts back to g. As for output Y , essentially the same story holds. In the transition, output

grows faster than n +g (the steady state rate of growth for Y ). As the new steady state is reached, output

growth reverts back to n +g.

c.) Now consider Chinas situation after any adjustments to the new saving rate have taken place. Is

there a theoretical possibility that the level of Chinese saving will be too high, in the sense that the new

steady-state level of living standards is lower that it would be with a lower saving rate? What real-world

data could you use to study whether Chinese saving is higher-than-optimal in this sense? And would a too

high savings rate be Pareto optimal with respect to dierent generations in China?

Answer: The savings rate will be too high if the new steady-state level of capital-per-eective-worker

k

is above the Golden Rule level k

GR

. Students should make clear that the level of consumption-per-

worker is lower than optimal at the Golden Rule. (The growth rate of consumption-per-worker in steady

1

state is always g, regardless of whether we are at the Golden Rule or not. Above the Golden Rule level of

k

, we have

MPK < n + +g.

How can we use real-world data to gure this whether this condition holds? The main problem is that we

dont observe MPK directly. One way to infer it is to use the fact that real interest rate r should be close

to MPK due an arbitrage relationship between physical capital and bonds. (This arbitrage relationship

is complicated by the fact that holding capital is risky, and by the potential for capital gains, but its okay

if students ignored those issues here.) Also, in steady state, the rate of growth in the economy is just n+g.

So if the real interest rate is lower than the steady-state growth rate of output, then we are likely to be

below the Golden Rule. Another way to do this, described by Mankiw on p. 244 of the 8th edition of his

intermediate text, it to use the fact that is equal to the share of output received by owners of capital, or

MPKK

Y

. Divide this (observable) fraction by the (observable) capital-output ratio

K

Y

to back out MPK.

You can then back out the depreciation rate by a similar method: Divide to the total share of output lost

to depreciation each year

K

Y

by the capital-output ratio

K

Y

. We now have both MPK and , so we can

compare the resulting MPK to the growth rate of the aggregate economy Y . Finally, if we have a k

that is above the Golden Rule level, then the economy is Pareto inecient. We can make future generations

better o by having the current generation consume more today.

d.) For this part of the question, suppose you are told that the shift toward higher saving occurred at the

same time that three other economic changes occurred in China. First, the Chinese welfare state became

less generous, in that free housing was no longer oered to young workers. Second, government spending

on social programs like unemployment benets and health care was also reduced. (No more free knee

replacements or liver transplants.) Third, employment became more unstable as the right to a lifetime job

was ended. How might standard models of consumption link these economic changes to the drop in saving?

Given your answer, how might the development of Chinas private-sector nancial systemto something

that resembles the U.S. private-sector nancial systemaect Chinese saving rates? (Note: Dont worry

about incorporating the eect of the reforms in your answers to the previous parts of this question. The

reforms are relevant for this part of the question only.)

Answer: This question implies that savings went up for two reasons. First, precautionary savings on

the part of households is higher due to the greater risk of unemployment and health shocks. Second, the

end of free government housing means that young people have to save to buy a house. The question should

be weighted so that most of the points given in this part come from the precautionary piece, because the

housing angle isnt as obvious.

Regarding precautionary savings: If Chinese residents have to insure themselves against big health

shocks, or the loss of jobs, then their savings rates will rise. This will be inecient in the sense that all

Chinese residents will be saving at very high rates even though only a portion of them will actually suer

unemployment or health shocks. Note, however that health shocks are likely to be idiosyncratic, while

unemployment shocks are likely to have a business cycle component. Regarding saving for housing: Life-

cycle models generally predict that young people are net savers, building up wealth to spend in retirement.

But if we add housing to the model, some of the saving that young people do could take the form of saving

to buy a house.

How are nancial markets relevant here? Two functions of nancial markets are to spread risk and

to match savers to investors. Formal insurance markets help spread risk by allowing people to pay small

premiums to avoid catastrophic expenses, such as those that might arise via health shocks or other major

idiosyncratic disasters (like the loss of a home due to re). Financial markets can also allow people to go

into debt for these types of expenses if they dont have insurance, then pay o the debt later. If these types

of insurance features are not available, then we might see older people refuse to draw down their savings,

for fear that they will be hit with a big health shock. Finally, if nancial markets are not developed enough

to allow young people to take out mortgages, they will have to save 100% of the purchase price of a house,

rather than a much smaller downpayment.

2

The development of nancial markets, like health insurance or mortgages, would therefore be expected

to lower Chinas saving rate. But importantly, private-sector markets can only insure against idiosyncratic

shocks. Thats why there is no private insurance against business-cycle related shocks.

Question 2. (20 minutes) For the past several years, Greece, a country that uses the euro, has endured

a serious recession. Many people have argued that Greece should undertake a scal expansion in order to

lower its unemployment rate. The question asks you to evaluate that recommendation. As you answer it,

assume that Greece is a small open economy (SOE) with perfect capital mobility and a xed exchange rate.

Use graphs when necessary.

a.) In general, can an SOE with xed exchange rates raise short-run output with a scal expansion? If

so, how are the components of output (consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports)

likely to change, if at all? What about the real interest rate and the real exchange rate? Does it matter

whether the expansion comes about due to higher government purchases G or lower taxes T?

Answer: This part asks students to report what happens in one of the standard Mundell-Fleming cases:

A scal expansion under xed rates. The IS

curve shifts out. To maintain the xed rate, the LM

curve

shifts out endogenously. Output rises. Investment stays constant and the real interest rate (which is pinned

down at r

) does not move either. The same is true for net exports and the nominal exchange rate (which

of course is xed). Since we are in the short run here, we assume that the ratio of price levels

P

P

is xed,

too, so the real exchange rate also stays the same. If the scal expansion takes place because of an increase

in G, then G rises and consumption C rises because of the higher level of output Y . If the expansion is due

to lower taxes, then G remains constant and C rises due both to the tax cut and to the higher level of Y .

b.) Now think about Greeces specic situation. One reason many analysts disagree with the benets

of a scal expansion in Greece is that they believe such an expansion will undermine the condence of

Greeces international creditors. That is, these analysts believe that if Greece undertakes a scal expansion,

international creditors will lose condence in the Greek governments ability to pay its bills, and will

therefore require higher compensation to hold Greek debt. If these critics are correct, how would a loss of

international condence in Greece aect your answer above?

Answer: This part of the question deals with an increase in country risk for an SOE with xed rates.

The higher interest rate shifts the IS

curve back. At the same time, the LM and LM

both shift back

in order to maintain the xed rate. The higher interest rate reduces investment I and therefore osets the

eects of the initial scal expansion. To the extent that the eect on output is lower, so is the multiplier

eect on consumption.

c.) In theory, could the eects of the loss of condence described in part b.) be so severe as to cause total

Greek output to decline after the scal expansion? Explain how your answer aects the debate over whether

Greece should choose a scal expansion on one hand or scal austerity on the other.

Answer: Yes. Once international creditors lose condence in a currency, the country risk premium

might rise so much as to completely oset or even swamp the initial increase in output that arises from the

scal expansion. The problem is that it is very hard to know how creditors will react to a scal expansion.

The reaction of creditors to a scal expansion determines whether the expansion will work, but these

expectations are impossible to know for certain before the expansion takes place. The same is true, but

the way, for scal contractions. Countries like Greece may choose austerity, hoping that a resulting drop in

country risk will raise output. But no one can know for certain whether this strategy will work.

3

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Macroecon F21Dokumen4 halamanMacroecon F21Samad Ashraf MemonBelum ada peringkat

- Taxes On Savings: Jonathan Gruber Public Finance and Public PolicyDokumen51 halamanTaxes On Savings: Jonathan Gruber Public Finance and Public PolicyGaluh WicaksanaBelum ada peringkat

- Solutions Williamson 3e IM 05Dokumen10 halamanSolutions Williamson 3e IM 05Diaconu MariannaBelum ada peringkat

- Intermediate Macro 1st Edition Barro Solutions ManualDokumen6 halamanIntermediate Macro 1st Edition Barro Solutions ManualMitchellSullivanbfepo100% (14)

- IGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012Dokumen8 halamanIGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012manish.cdmaBelum ada peringkat

- FACTORS THAT SHIFT THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONDokumen16 halamanFACTORS THAT SHIFT THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONIlma LatansaBelum ada peringkat

- Keynesian Consumption and Investment PDFDokumen17 halamanKeynesian Consumption and Investment PDFGayle AbayaBelum ada peringkat

- Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8th Edition Osullivan Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDokumen36 halamanMacroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8th Edition Osullivan Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFStevenCookexjrp100% (9)

- Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8th Edition Osullivan Solutions ManualDokumen15 halamanMacroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8th Edition Osullivan Solutions Manualcharleshoansgb3y100% (30)

- Chapeter 24 - Solutions PDFDokumen7 halamanChapeter 24 - Solutions PDFAltmash AsifBelum ada peringkat

- IGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012Dokumen8 halamanIGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012manuraj4Belum ada peringkat

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezDokumen16 halamanSolution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezVanessaMerrittdqes100% (35)

- Chap 22Dokumen18 halamanChap 22Syed HamdanBelum ada peringkat

- Unit-1 Introduction To Macroeconomics and National Income AccountingDokumen39 halamanUnit-1 Introduction To Macroeconomics and National Income AccountingDaniel ParkerBelum ada peringkat

- Do-the-Rich-Save-More-in-Latin-America BIDDokumen33 halamanDo-the-Rich-Save-More-in-Latin-America BIDjessalazBelum ada peringkat

- IGNOU MEC-004 Free Solved Assignment 2012Dokumen8 halamanIGNOU MEC-004 Free Solved Assignment 2012manuraj4Belum ada peringkat

- Dwnload Full Macroeconomics Fourteenth Canadian Edition Canadian 14th Edition Ragan Solutions Manual PDFDokumen35 halamanDwnload Full Macroeconomics Fourteenth Canadian Edition Canadian 14th Edition Ragan Solutions Manual PDFdyestuffdynasticybwc89100% (11)

- Government Macro Intervention: Ideas For Answers To Progress QuestionsDokumen4 halamanGovernment Macro Intervention: Ideas For Answers To Progress QuestionsChristy NyenesBelum ada peringkat

- IGNOU MEC-004 Free Solved Assignment 2012Dokumen8 halamanIGNOU MEC-004 Free Solved Assignment 2012manish.cdmaBelum ada peringkat

- Finance Public in Models of Economic GrowthDokumen39 halamanFinance Public in Models of Economic GrowthLamine keitaBelum ada peringkat

- Household Saving in LDCs: Credit Markets, Insurance and WelfareDokumen21 halamanHousehold Saving in LDCs: Credit Markets, Insurance and WelfareALSCBelum ada peringkat

- Art On DebtDokumen24 halamanArt On DebtJosé Antonio PoncelaBelum ada peringkat

- Economics Assignment QuestionsDokumen5 halamanEconomics Assignment Questionsعبداللہ احمد جدرانBelum ada peringkat

- Eco 302 The Fundamentals of Economic Growth Notes 1Dokumen16 halamanEco 302 The Fundamentals of Economic Growth Notes 1lubisithembinkosi4Belum ada peringkat

- Consumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewDokumen18 halamanConsumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewGeorge WagihBelum ada peringkat

- Macro 4Dokumen15 halamanMacro 4Rajesh GargBelum ada peringkat

- Williamson 3e IM 04Dokumen15 halamanWilliamson 3e IM 04Siwei Zhang100% (1)

- Consumption and SavingDokumen6 halamanConsumption and Savingmah rukhBelum ada peringkat

- A Simple Model of Inequality, Occupational Choice, and DevelopmentDokumen22 halamanA Simple Model of Inequality, Occupational Choice, and DevelopmentStefania RamonaBelum ada peringkat

- Public Debt and Low Interest RateDokumen48 halamanPublic Debt and Low Interest RategremiaBelum ada peringkat

- Chap 24Dokumen22 halamanChap 24Syed HamdanBelum ada peringkat

- Business Cycle FeaturesDokumen10 halamanBusiness Cycle FeaturesLaura Kwon100% (1)

- Answers Key To Midterm-Exam - ECON221Dokumen9 halamanAnswers Key To Midterm-Exam - ECON221Abdullah SarwarBelum ada peringkat

- Homework Week 1 MacroeconomicsDokumen5 halamanHomework Week 1 MacroeconomicsThu Phương PhạmBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Solution Guide SESSION: (2017-2018) : AnswersDokumen11 halamanAssignment Solution Guide SESSION: (2017-2018) : Answersnitikanehi100% (1)

- Solow Model Best ExplainDokumen42 halamanSolow Model Best Explainjaiswal.utkarshBelum ada peringkat

- 16265-BPEA-Sp22 Mankiw WEBDokumen13 halaman16265-BPEA-Sp22 Mankiw WEBImamul Ma'arifBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Fluctuations and Aggregate Demand Supply CurvesDokumen3 halamanEconomic Fluctuations and Aggregate Demand Supply CurvessalvimomBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 3: Business Cycle, Inflation and UnemploymentDokumen28 halamanChapter 3: Business Cycle, Inflation and UnemploymentChristian Jumao-as MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Macroeconomics 5th Edition Williamson Solutions ManualDokumen12 halamanMacroeconomics 5th Edition Williamson Solutions Manuallouisbeatrixzk9u100% (29)

- Solution To ECON100B Fall 2023 Midterm 2 PDFDokumen19 halamanSolution To ECON100B Fall 2023 Midterm 2 PDFmaobangbang21Belum ada peringkat

- Public Debt and Low Interest Rates by Olivier Blanchard PDFDokumen37 halamanPublic Debt and Low Interest Rates by Olivier Blanchard PDFIván WdiBelum ada peringkat

- Macroeconomics Assignment Compares Friedman's Monetary ViewsDokumen12 halamanMacroeconomics Assignment Compares Friedman's Monetary ViewsSajid AliBelum ada peringkat

- 5th Sem (Macro-Economics) Super 25 Question & AnswerDokumen17 halaman5th Sem (Macro-Economics) Super 25 Question & Answersadfeel145Belum ada peringkat

- Answer Guide and Final Exam EWMBA201B Spring 2018 - RedactedDokumen11 halamanAnswer Guide and Final Exam EWMBA201B Spring 2018 - Redactedkr6ftymgq7Belum ada peringkat

- CH3Dokumen5 halamanCH3盧愷祥Belum ada peringkat

- Introduction To The Equilibrium Model: Intermediate MacroeconomicsDokumen8 halamanIntroduction To The Equilibrium Model: Intermediate MacroeconomicsDinda AmeliaBelum ada peringkat

- Economics: Chapter 12: Measuring The EconomyDokumen15 halamanEconomics: Chapter 12: Measuring The EconomyMay Samolde MagallonBelum ada peringkat

- Principles of Economics & Bangladesh Economy (PBE)Dokumen13 halamanPrinciples of Economics & Bangladesh Economy (PBE)Joshua SmithBelum ada peringkat

- A08 13 Test Solow ModelDokumen6 halamanA08 13 Test Solow ModelTopsuz AlanBelum ada peringkat

- RD2 UDokumen5 halamanRD2 UAnish BhusalBelum ada peringkat

- The Regional Economist - July 2015Dokumen24 halamanThe Regional Economist - July 2015Federal Reserve Bank of St. LouisBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis Economic GrowthDokumen6 halamanThesis Economic Growthfjn3d3mc100% (2)

- Full Download Intermediate Macro 1st Edition Barro Solutions ManualDokumen35 halamanFull Download Intermediate Macro 1st Edition Barro Solutions Manualeustacegabrenas100% (35)

- Macroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions ManualDokumen35 halamanMacroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions Manualsinapateprear4k100% (17)

- CourseBook AE Curve - AnswersDokumen17 halamanCourseBook AE Curve - AnswersMomoBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 11 Dan 12Dokumen8 halamanChapter 11 Dan 12Andi AmirudinBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture Note #3Dokumen4 halamanLecture Note #3spadha reddyBelum ada peringkat

- Final QuestiionsDokumen5 halamanFinal QuestiionspollyBelum ada peringkat

- HRP. Chapter 1Dokumen11 halamanHRP. Chapter 1cankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Somalia and Somaliland CulDokumen4 halamanUnderstanding Somalia and Somaliland CulcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Application or Motivation LrtterDokumen1 halamanApplication or Motivation LrttercankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Moh BusinessDokumen2 halamanMoh BusinesscankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 ShakuuriDokumen4 halamanChapter 1 ShakuuricankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- First MaterialDokumen4 halamanFirst MaterialcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- First MaterialDokumen4 halamanFirst MaterialcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- WorldQuant University - Privacy PolicyDokumen9 halamanWorldQuant University - Privacy PolicycankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Updated Mo Prefactory - NycDokumen11 halamanUpdated Mo Prefactory - NyccankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Last Note InfrastructureDokumen5 halamanLast Note InfrastructurecankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Your Name: Recipient Name Title / Company AddressDokumen1 halamanYour Name: Recipient Name Title / Company AddressJohn Lester TanBelum ada peringkat

- Your Name: Recipient Name Title / Company AddressDokumen1 halamanYour Name: Recipient Name Title / Company AddressJohn Lester TanBelum ada peringkat

- First MaterialDokumen4 halamanFirst MaterialcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Managment AccountingDokumen14 halamanManagment AccountingMuhammadFahadBelum ada peringkat

- Mo HaaaaaaajjjjygyvlyrcyecuydDokumen1 halamanMo HaaaaaaajjjjygyvlyrcyecuydcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Chap 006Dokumen85 halamanChap 006cankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Somaliland Secondary School Final Exam ResultDokumen2 halamanSomaliland Secondary School Final Exam ResultcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- First MaterialDokumen4 halamanFirst MaterialcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Best of The BestDokumen1 halamanBest of The BestcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Farhad Does Not Know How To WriteDokumen15 halamanFarhad Does Not Know How To WritecankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- International Accounting Standards BoardDokumen5 halamanInternational Accounting Standards BoardcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Development Plan U 1 L 10Dokumen7 halamanPersonal Development Plan U 1 L 10cankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Development Plan U 1 L 10Dokumen7 halamanPersonal Development Plan U 1 L 10cankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- About Bank AsiaDokumen21 halamanAbout Bank AsiacankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- ParkinsonsDokumen38 halamanParkinsonscankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- NTTDokumen22 halamanNTTcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Study Blank TimetableDokumen2 halamanStudy Blank TimetableObfuBelum ada peringkat

- International Accounting Standards BoardDokumen5 halamanInternational Accounting Standards BoardcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- About Bank AsiaDokumen21 halamanAbout Bank AsiacankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- NTTDokumen22 halamanNTTcankawaabBelum ada peringkat

- Advanced Zimbabwe Tax Module 2011 PDFDokumen125 halamanAdvanced Zimbabwe Tax Module 2011 PDFCosmas Takawira88% (24)

- Accountancy Answer Key Class XII PreboardDokumen8 halamanAccountancy Answer Key Class XII PreboardGHOST FFBelum ada peringkat

- Settlement Rule in Cost Object Controlling (CO-PC-OBJ) - ERP Financials - SCN Wiki PDFDokumen4 halamanSettlement Rule in Cost Object Controlling (CO-PC-OBJ) - ERP Financials - SCN Wiki PDFkkka TtBelum ada peringkat

- Sap CloudDokumen29 halamanSap CloudjagankilariBelum ada peringkat

- Swift MessageDokumen29 halamanSwift MessageAbinath Stuart0% (1)

- Syllabus Corporate GovernanceDokumen8 halamanSyllabus Corporate GovernanceBrinda HarjanBelum ada peringkat

- Lessons From The Enron ScandalDokumen3 halamanLessons From The Enron ScandalCharise CayabyabBelum ada peringkat

- Take RisksDokumen3 halamanTake RisksRENJITH RBelum ada peringkat

- Contract CoffeeDokumen5 halamanContract CoffeeNguyễn Huyền43% (7)

- Core Banking PDFDokumen255 halamanCore Banking PDFCông BằngBelum ada peringkat

- Fin 416 Exam 2 Spring 2012Dokumen4 halamanFin 416 Exam 2 Spring 2012fakeone23Belum ada peringkat

- Analisis Cost Volume Profit Sebagai Alat Perencanaan Laba (Studi Kasus Pada Umkm Dendeng Sapi Di Banda Aceh)Dokumen25 halamanAnalisis Cost Volume Profit Sebagai Alat Perencanaan Laba (Studi Kasus Pada Umkm Dendeng Sapi Di Banda Aceh)Fauzan C LahBelum ada peringkat

- Randy Gage Haciendo Que El Primer Circulo Funciones RG1Dokumen64 halamanRandy Gage Haciendo Que El Primer Circulo Funciones RG1Viviana RodriguesBelum ada peringkat

- Israel SettlementDokumen58 halamanIsrael SettlementRaf BendenounBelum ada peringkat

- IQA QuestionsDokumen8 halamanIQA QuestionsProf C.S.PurushothamanBelum ada peringkat

- Ctpat Prog Benefits GuideDokumen4 halamanCtpat Prog Benefits Guidenilantha_bBelum ada peringkat

- FM S Summer Placement Report 2024Dokumen12 halamanFM S Summer Placement Report 2024AladeenBelum ada peringkat

- GEAR 2030 Final Report PDFDokumen74 halamanGEAR 2030 Final Report PDFAnonymous IQlte8sBelum ada peringkat

- Econ 201 MicroeconomicsDokumen19 halamanEcon 201 MicroeconomicsSam Yang SunBelum ada peringkat

- Reporting Outline (Group4 12 Abm1)Dokumen3 halamanReporting Outline (Group4 12 Abm1)Rafaelto D. Atangan Jr.Belum ada peringkat

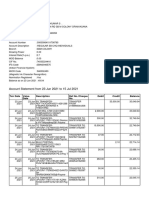

- Account Statement From 23 Jun 2021 To 15 Jul 2021Dokumen8 halamanAccount Statement From 23 Jun 2021 To 15 Jul 2021R S enterpriseBelum ada peringkat

- Mba-Cm Me Lecture 1Dokumen17 halamanMba-Cm Me Lecture 1api-3712367Belum ada peringkat

- Technical Analysis GuideDokumen3 halamanTechnical Analysis GuideQwerty QwertyBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Sample Report BSR For S4hanaDokumen79 halamanCustomer Sample Report BSR For S4hanaHarpy AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- 3m Fence DUPADokumen4 halaman3m Fence DUPAxipotBelum ada peringkat

- Tourism and Hospitality FlyerDokumen2 halamanTourism and Hospitality FlyerHarsh AhujaBelum ada peringkat

- Allen Solly (Retail Managemant Project Phase 1) (Chandrakumar 1501009)Dokumen9 halamanAllen Solly (Retail Managemant Project Phase 1) (Chandrakumar 1501009)Chandra KumarBelum ada peringkat

- IDA - MTCS X-Cert - Gap Analysis Report - MTCS To ISO270012013 - ReleaseDokumen50 halamanIDA - MTCS X-Cert - Gap Analysis Report - MTCS To ISO270012013 - ReleasekinzaBelum ada peringkat

- General Electric Marketing MixDokumen6 halamanGeneral Electric Marketing MixMohd YounusBelum ada peringkat

- DPR Plastic Waste ManagementDokumen224 halamanDPR Plastic Waste ManagementShaik Basha100% (2)