Use of Aromatherapy Products and Increased Risk of Hand Dermatitis in Massage Therapists

Diunggah oleh

Nilamdeen Mohamed Zamil0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

34 tayangan6 halamanc

Judul Asli

991

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inic

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

34 tayangan6 halamanUse of Aromatherapy Products and Increased Risk of Hand Dermatitis in Massage Therapists

Diunggah oleh

Nilamdeen Mohamed Zamilc

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 6

Use of Aromatherapy Products and Increased Risk

of Hand Dermatitis in Massage Therapists

Glen H. Crawford, MD; Kenneth A. Katz, MD, MSc; Elliot Ellis, MD; William D. James, MD

Objectives: To determine the 12-month prevalence of

hand dermatitis among massage therapists, to investi-

gate a potential association between hand dermatitis and

the use of aromatherapy products, and to study poten-

tial associations with other known risk factors for hand

dermatitis.

Design: Mailed survey.

Setting: Philadelphia, Pa.

Participants: Members of a national massage therapy or-

ganization who live in the greater Philadelphia region.

MainOutcomeMeasures: Self-reported and symptom-

based prevalences of hand dermatitis.

Results: The number of respondents was 350(57%). The

12-monthprevalenceof handdermatitisinsubjectswas15%

by self-reported criteria and 23% by a symptom-based

method. Inmultivariateanalysis, statisticallysignificant in-

dependent riskfactors for self-reportedhanddermatitis in-

cluded use of aromatherapy products in massage oils, lo-

tions, or creams (odds ratio, 3.27; 95% confidence inter-

val, 1.53-7.02; P=.002)andhistoryof atopicdermatitis(odds

ratio, 8.06; 95%confidence interval, 3.39-19.17; P.001).

Conclusions: The prevalence of hand dermatitis in mas-

sage therapists is high. Significant independent risk fac-

tors include use of aromatherapy products inmassage oils,

creams, or lotions and history of atopic dermatitis.

Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:991-996

H

AND DERMATITIS CONSTI-

tutes 80% or more of

cases of work-relatedder-

matitis in the United

States.

1

Handdermatitis is

a serious condition and often results in a

change of occupation, interference withso-

cial activities, and even permanent dis-

ability.

2

As such, both irritant and aller-

gic contact dermatitis are considered

priority research areas as outlined in the

National Occupational Research Agenda

introduced in 1996 by the National Insti-

tute for Occupational Safety and Health.

3

Massage is becoming increasingly

popular. Current estimates indicate that

there are between 260000 and 290000

practicing therapists and massage therapy

students in the United States today, which

is more than twice the number in 1996

(120000 to 160000).

4

Many massage

therapists may be exposed to multiple fac-

tors known to increase the risk of devel-

oping hand dermatitis, such as wet work,

frequent hand washing,

5

fragrance, dyes,

detergents, latex,

6

and other irritants and

allergens found in massage oils, creams,

and lotions.

7

Aromatherapy, the therapeutic use of

essential oils, has also gained increased

popularityinthe UnitedStates. Essential oils

arearomaticsubstances extractedfromflow-

ers, plants, and wood resins by a variety of

methods, such as distillation or macera-

tion. Allergic contact dermatitis to aroma-

therapy products has beendemonstratedin

several case reports and small case se-

ries.

8-17

The spectrum of skin reactions in-

cludes allergic contact dermatitis, irritant

contact dermatitis, contact urticaria, and

phototoxic reactions.

18-20

Observations in

our clinic and a case series by Taraska and

Pratt

13

suggest anincrease inthe use of aro-

matherapy oils by massage therapists and

a possible heightened risk of hand derma-

titis. To date, no large study, to our knowl-

edge, has investigated hand dermatitis in

massage therapists. The objectives of this

questionnaire-based study were (1) to de-

termine the prevalence of hand dermatitis

among massage therapists in the greater

Philadelphia region, (2) to specifically as-

sess risk associated with the use of aroma-

therapy products, and (3) to investigate if

there are associations withother knownrisk

factors for hand dermatitis.

STUDY

From the Department of

Dermatology (Drs Crawford,

Katz, and James), University of

Pennsylvania Medical Center,

Philadelphia; and Department

of Medicine, Yale University

School of Medicine, New

Haven, Conn (Dr Ellis). The

authors have no relevant

financial interest in this article.

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

991

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

METHODS

SURVEY DESIGN

After approval by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional

Review Board, questionnaires were sent to all 618 members of

the American Bodywork and Massage Professionals in the Phila-

delphia area. The American Bodywork and Massage Profes-

sionals is a membership organization that serves massage, body-

work, somatic, and aesthetic professionals in the United States.

The survey was performed by a modification of a common tech-

nique for conducting mail surveys.

21

Three mailings were per-

formed, which included an introductory letter followed by

2 mailings with standardized questionnaires.

QUESTIONNAIRE

This questionnaire was broadly based on a standard occupa-

tional skin questionnaire newly developed by the Nordic Skin

Study Group (Nordic Occupational Skin Questionnaire

NOSQ-2002/LONG)

22

and tailored to the assessed potential ex-

posures and risk factors for massage therapists. Further adjust-

ments to the questionnaire were made in response to feedback

from a small group of massage therapists to whom the ques-

tionnaire was piloted.

CASE DEFINITIONS

In prior questionnaire-based studies,

23-25

2 methods have been

used to define cases of hand dermatitis: (1) self-reported diag-

noses, based on respondents answering yes to a question such

as Have youhad eczema onyour hands inthe past 12 months?

and (2) symptom-based diagnoses, based on meeting a set of

complex predetermined criteria froma list of skin complaints.

Case definitions for current, chronic or recurrent, and history

of hand dermatitis are provided in the Figure. Diagnoses of

hand dermatitis by symptom-based criteria were created based

on an adaptation of features fromseveral of the most-accepted

case definitions used in previous studies (Figure).

22,25-27

Previous studies have demonstrated reasonable associa-

tions between self-reported aggravators of skin symptoms and

clinical skin testing to the reported substances.

28,29

Self-re-

ported aggravators of skin symptoms were obtained from re-

sponses to the question, What do you consider to be the

most important things at the workplace that worsen your

hand dermatitis? Response choices or categories were deter-

mined by a pilot study, which involved 20 individuals from

the target population, as well as a list of factors known to in-

fluence hand dermatitis and found to be potential exposures

in this population.

To estimate the impact of hand dermatitis on quality of

life, a series of questions were generated fromthe NOSQ-2002/

LONG.

22

The answers to these questions generally reflect the

severity of the skin condition and its impact on the workplace.

Criteria for inclusion in the study included returning the com-

pleted questionnaire, reporting current employment as a mas-

sage therapist or bodyworker, and working at least 1 h/wk or

with at least 1 client per week.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using univariable and multivariable logis-

tic regression models. Multivariable models included vari-

ables significant on univariable analyses, as well as sex and his-

tory of atopic dermatitis. Multivariable models were tested for

significance of interaction among variables. Subjects for whom

data were missing for a particular variable were excluded from

analyses that included that variable. All analyses were per-

formed using Stata statistical software version 6.0 (Stata Corp,

College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

Three hundredfifty completedquestionnaires (57%) were

returned before the deadline for analysis of data. Fifty-

eight respondents failed to meet inclusion criteria, which

required reporting current employment as a massage

therapist and at least 1 client or 1 hour of work in this

capacity per week. The remaining 292 subjects were in-

cluded in the analysis.

The study population included 246 women (84%)

and 43 men (15%). Three respondents chose not to re-

veal their sex. There were 261 therapists (89%) who used

modalities that required frequent use of massage oils, and

30 (10%) who used modalities without oils. One respon-

dent did not answer this question. Thirty-one massage

therapists (11%) fulfilled criteria for atopic dermatitis.

One hundred fifty-eight (54%) reported nasal allergy, and

38 (13%) reported history of asthma. The median fre-

quency of hand washing was 10 times per day (range,

1-101) (Table 1).

Overall, 47% reported use of aromatherapy prod-

ucts in oils, creams, or lotions, and 39% reported use of

aromatherapy candles, burners, or incense. Overall, only

21% of respondents reported ever having used protec-

tive gloves while working. The most common massage

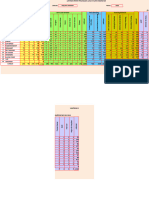

1. History of hand dermatitis by self-report

Answering yes to the written question Have you ever had dermatitis

(rash, eczema) involving your hands?

2. Current hand dermatitis (point prevalence)

Answering yes to the written question Have you ever had dermatitis

(rash, eczema) involving your hands?

and

Answering I have it at the moment to the written question When did

you last have dermatitis on your hands?

3. Chronic or recurrent hand dermatitis

Answering yes to the written question Have you ever had dermatitis

(rash, eczema) involving your hands?

and

Answering I have it at the moment, not at the moment but within the

past 3 months, or between 3 and 12 months ago to the written question

When did you last have dermatitis on your hands?

and

Answering only once but for 2 weeks or more or more than once or has

been persistent to the written question How often have you had dermatitis

on your hands?

4. Definition of cases by symptom-based criteria

Marking 2 or more of the following in response to the question What skin

symptoms have you had on your hands during the past 12 months?

Redness

Dry skin with scaling or flaking

Fissures or deep cracks

Weeping or oozing or crusts

Tiny water blisters (vesicles)

Papules (small bumps)

Rapidly appearing itchy hives, wheals, or welts (urticaria)

or

Marking 1 of the symptoms listed above and 2 or more of the following:

Itching

Burning, prickling, or stinging of the skin

Skin tenderness

Aching or pain

Figure. Definition of cases.

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

992

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

modalities or techniques used were Swedish massage

(70%), deep tissue or myofascial (30%), Reiki (5.1%), Shi-

atsu (7.9%), neuromuscular release (5.8%), reflexology

(4.1%), craniosacral (2.4%), acupressure (2.1%), lym-

phatic (1.0%), and trigger point (0.7%).

HAND DERMATITIS

The 12-month prevalence of hand dermatitis by self-

reportedcriteria was 15%(n=45). This included44 (17%)

of the oil-exposedtherapists and1therapist (2%) whoused

a no-oil modality. The prevalence of current hand derma-

titis was 5% (n=13). Chronic or recurrent hand dermati-

tis was reported in 24 respondents (8%). The locations of

skin symptoms in self-reported cases were as follows: fin-

gertips (36%), palms (33%), dorsum(49%), wrists (27%),

and forearms (16%). By symptom-based methods, the 12-

monthprevalence of handdermatitis was 23%(n=66). The

following hand symptoms were most commonly reported

inrespondents withsymptom-based cases of hand derma-

titis: erythema (70%), dryness with scale (77%), fissures

(46%), pruritus (36%), and aching or pain (35%).

RISK FACTORS

The effects of possible risk factors (sex, age, atopic back-

ground, frequency of hand washing, use of aroma-

therapy products, use of protective gloves, amount of

work) on a reported history of hand dermatitis were in-

vestigated (Table 2). In univariate analysis, the risk of

hand dermatitis was higher for massage therapists with

histories of atopic dermatitis (odds ratio [OR], 8.69; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 3.87-19.53; P.01) andfor those

who used aromatherapy products in oils, lotions, or

creams (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.33-5.09; P=.01) (Table 2).

There was some evidence of increased risk for women

(OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 0.82-9.38; P=.10) and in those who

frequently usedmassage oils, creams, or lotions (OR, 5.73;

95% CI, 0.76-43.23; P=.09).

In multivariate analysis, risk remained high for mas-

sage therapists who used aromatherapy products in mas-

sage oils, creams, or lotions (OR, 3.27; 95% CI, 1.53-

7.02; P=.002) and for those with histories of atopic

dermatitis (OR, 8.06; 95%CI, 3.39-19.17; P.001). Sex

(OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 0.65-12.94; P=.16; for women com-

pared with men) and age (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.57-1.16;

P=.25; for every additional 10 years) of the massage thera-

pists and the use of massage oils, creams, or lotions were

not significantly associated with hand dermatitis in mul-

tivariate analysis. There were no significant interactions

between atopic dermatitis and use of aromatherapy prod-

ucts (Table 3).

When asked about aggravators of skin symptoms in

those with self-reported hand dermatitis, 87% reported

at least 1 item, including frequent hand washing (23, or

51%); friction and physical trauma (10 or 22%); mas-

sage oils, creams, or lotions (11 or 24%); other chemi-

cals (18 or 40%); other aggravating factors (20 or 44%);

and work with wet hands (2 or 4%). Only 2 (4%) of these

respondents reported that the addition of aromatherapy

products to their oils, creams, or lotions aggravated their

skin symptoms.

Table 1. Patient Demographic Data

Variable Result

Respondents who met study criteria, No. 292

Age, mean (SD), y 42.9 (10.7)

Duration of employment (range), y 5 (1-29)

Hours of work per week (range) 12.5 (0-48)

Clients per week (range) 11 (0-50)

Sex, No. (%)

F 246 (84)

M 43 (15)

Atopic background, No. (%)

Total 172 (59)

Atopic dermatitis 31 (11)

Nasal allergy 158 (54)

Asthma 38 (13)

Hand washing, No. of times per day (range) 10 (1-101)

Use of aromatherapy products, No. (%)

Total 199 (68)

In oils 137 (47)

In candles, burners, or incense 113 (39)

Use of protective gloves while working, No. (%) 62 (21)

Table 2. Risk Estimates for Self-reported Cases

of Hand Dermatitis (Univariate Analysis)

Variable OR (95% CI)

P

Value

Women compared with men 2.77 (0.82-9.38) .10

Age for every additional 10 y 0.79 (0.58-1.07) .13

History of atopy

Any atopy 1.92 (0.92-4.02) .08

Asthma 1.00 (0.39-2.55) .99

Nasal allergy 1.67 (0.85-3.28) .13

Atopic dermatitis 8.69 (3.87-19.53) .001

Frequent use of massage oils,

creams, or lotions

5.73 (0.76-43.23) .09

Hand washing for every additional

10 washes per day

1.15 (0.83-1.58) .40

Use of aromatherapy products 1.99 (0.91-4.33) .08

In oils, lotions, creams 2.60 (1.33-5.09) .01

In candles, burners, incense 1.19 (0.62-2.26) .60

Use of protective gloves

sometimes or always vs no

gloves

1.82 (0.90-3.70) .10

Working for every additional 10

h/wk

1.28 (0.93-1.75) .12

Working, for every additional 10

clients per week

1.13 (0.79-1.60) .51

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Table 3. Risk Estimates for Self-reported Cases of Hand

Dermatitis (Multivariate Analysis)

Variable OR (95% CI)

P

Value

Women compared with men 2.91 (0.65-12.94) .16

Age, for every additional 10 years 0.81 (0.57-1.16) .25

Atopic dermatitis 8.06 (3.39-19.17) .001

Aromatherapy, in oils, lotions, creams 3.27 (1.53-7.02) .002

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

993

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

IMPACT ON WORK ACTIVITIES

In those respondents who met criteria for self-reported

hand dermatitis, impact on work activities were listed as

follows: have touse protective gloves (13%), hadtochange

work tasks (7%), experienced negative attitudes by em-

ployer(s) or coworker(s) (2%), had a decrease in in-

come (4%), had to miss work (7%), and had to miss other

activities (13%).

COMMENT

In this study, the 12-month prevalence of hand derma-

titis in massage therapists was found to be 15% by self-

reported criteria and 22% by a symptom-based method.

This may represent a marked increase from the general

population, because prevalence rate determinations in

prior studies

30-32

have been in the range of 2%to 10%. In

multivariate analysis, statistically significant indepen-

dent risk for hand dermatitis was found with having a

history of atopic dermatitis and with having frequently

used aromatherapy products in oils, creams, or lotions.

RESPONSE AND BIAS

Atotal of 350 therapists (57%) returned completed ques-

tionnaires. Anoverestimationof prevalence might be pos-

sible given that individuals with hand dermatitis may be

more inclined to respond to a skin health survey.

PREVALENCE OF HAND DERMATITIS

Of the massage therapists surveyed in this study, the 12-

month prevalence of hand dermatitis was 23% by the

symptom-based method and 15%by self-report. Whereas

symptom-based methods tend to overestimate, self-

reported rates tend to underestimate true population

prevalence rates. Therefore, the true 12-month preva-

lence rate in this population of massage therapists is likely

withinthis range. The differences inrates by these 2 meth-

ods can be explained by their disparate sensitivities and

specificities as determined in prior studies

25,31,33,34

that in-

cluded methodologic validations. High negative predic-

tive values make standard symptom-based methods bet-

ter tools for screening purposes.

25,31,33,34

The highspecificity

of the self-reported method (in the range of 96.2%-

98.9%) makes this a better tool for the identification of

potential cases for further evaluation.

33

The prevalence rates found in this study for mas-

sage therapists are within the range of prevalence rates

previously found in other high-risk populations, such as

nurses,

25,31,35-37

farmers,

34

veterinarians,

38,39

flower indus-

try workers,

5,30,40

car mechanics,

33

and several other oc-

cupational subgroups.

32,41-45

Unfortunately, the investi-

gative methods used to assess hand dermatitis produce

inconsistent results based on differences in both the study

methods and the criteria used to define hand dermati-

tis.

5,7,23-25,33,34,42,46,47

Consequently, meaningful compari-

sons among different study populations are difficult.

To help rectify some of these problems, the Nordic

Council of Ministers recently released a standard set of

occupational skin disease questions to be used in epide-

miologic studies (NOSQ-2002/LONG; available at

http://www.ami.dk/english/redskaber/2.html).

22

This in-

strument will greatly facilitate work in the field of occu-

pational dermatology. In the next phase of this study, we

will conduct personal interviews and physical examina-

tions to confirm credible prevalence rates for hand der-

matitis in this population of massage therapists. In ad-

dition, patch testing may prove useful in identifying

specific chemicals inaromatherapy or other types of prod-

ucts that cause or aggravate hand dermatitis in this popu-

lation. In this study, we clearly outlined our case defi-

nitions for hand dermatitis by both self-reported and

symptom-based methods to provide a standardized ap-

proach to investigate hand dermatitis in future question-

naire studies.

PATTERN OF HAND DERMATITIS

The pattern of involvement of hand dermatitis can some-

times be a clue to causality. In this study, more respon-

dents reported dorsal hand symptoms (49%) than palmar

handsymptoms (33%). It is knownthat substantiallygreater

involvement of the dorsa of the hands as opposed to the

palms suggests allergic contact dermatitis if the allergencon-

tacts all areas of the hand equally.

48,49

One study

50

demon-

strated that patients with predominantly dorsal hand in-

volvement are more likely to have significant contact with

irritants and are more often atopic than those with palmar

predominance. Inanother study

51

conductedwith5700in-

dividuals in Sweden suspected of having allergic contact

dermatitis, statistical associations were foundbetweencer-

tainchemicals anddermatitis localizedto different sites on

the hands. Additionally, eruptions on the palms and sides

of thefingers areoftentheresult of dyshidroticeczemarather

than exposure to external contactants.

52

Mechanical fac-

tors have also beenshownto influence the patternof hand

dermatitis, resulting in so-called frictional contact derma-

titis.

53,54

One might expect trauma or friction to more of-

ten manifest on the fingertips or palms in massage thera-

pists. It is obvious that the patternof dermatitis onthe hands

is the result of a complex interplay between host suscep-

tibility and environmental or occupational exposures. An

explanation for the patterns of involvement in this popu-

lation of massage therapists will have to await the future

phases of this study, which will involve in-depth occupa-

tional histories, physical examinations, and patch testing.

DETERMINANTS OF HAND DERMATITIS

Massage therapists face multiple exposures that have been

shown to increase the risk of hand dermatitis in other

populations, such as water, perfumes, dyes, solvents, la-

tex,

6

and frequent hand washing.

5

Constitutional fac-

tors, such as history of atopic dermatitis

7,36,37,55-57

and fe-

male sex,

35,57-59

have also been demonstrated to influence

hand dermatitis in previous studies.

7

Inthis study, multivariate analysis demonstrated2sta-

tistically significant independent risk factors for hand der-

matitis inmassage therapists. These factors include the use

of aromatherapy products in oils, lotions, or creams (OR,

3.27; 95% CI, 1.53-7.02; P=.002) and a personal history

of atopicdermatitis (OR, 8.06; 95%CI, 3.39-19.17; P.001).

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

994

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

There was also some evidence to suggest an increased risk

for women compared with men (OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 0.65-

12.94; P=.16). However, this study may have had limited

power to detect differences in rates between men and

women. Statistical significance was likely not reached due

to the low number of men in this population (15%).

AROMATHERAPY PRODUCTS AND

ESSENTIAL OILS

Massage therapists in this study who met criteria for hand

dermatitis believedthat frequent handwashing (51%) and

the use of massage oils (24%) were the most important

aggravators of their skin symptoms. Many reports have

implicated aromatherapy products in the production of

contact allergy.

8-17

However, only 2 (4%) of these same

respondents listed aromatherapy products as potential

aggravators of their hand dermatitis.

Allergic contact dermatitis from essential oils has

been documented in several occupational subgroups, in-

cluding bar workers,

60

citrus fruit pickers,

61

hairdress-

ers,

62

beauticians,

63

aromatherapists,

9,11,14

and massage

therapists.

13

The most commonly cited specific oils in-

clude tea-tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia),

64-67

laven-

der,

12,62,68

jasmine,

12

rosewood,

12

lemon oils,

61

orange oils

(including oil of bergamot),

60,69,70

citronella, cassia oil,

71

ylang-ylang oil,

63

and clove oil.

72

The evaluation of potential essential oil allergy is ex-

tremely complicated. Chemical constituents are di-

verse, with as many as 100 distinct substances in any one

oil, and extracts from the same plant species can result

in varying ingredients and concentrations of chemicals.

The most common substances found are monoterpene

and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, monoterpene and ses-

quiterpene alcohols, esters, ethers, aldehydes, ketones,

and oxides. Additionally, it may be degradation byprod-

ucts withinthe skinthat actually cause sensitizationrather

than the chemicals in the bottled oils. Conversely, due

to the quenching effect, individual substances in an oil

mixture often interact in a way to reduce the sensitizing

potential of the individual component.

20

The consulting

physician indeed has to be truly knowledgeable and dili-

gent in the evaluation of potential essential oil allergy.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of therapeutic massage is rapidly gaining popu-

larity. Additionally, there has been a growing trend in

the use of natural remedies and aromatherapy products.

Massage therapists face multiple exposures known to in-

fluence handdermatitis, suchas wet work, fragrance, dyes,

detergents, latex, and other irritants and allergens found

in massage oils, creams, and lotions. This study demon-

strated a 12-month prevalence of hand dermatitis in mas-

sage therapists of 15%by a self-reported method and 23%

by a symptom-based method. This is a marked increase

from the results of most studies on prevalence rates in

the general population. In addition, statistically signifi-

cant independent associations were found between the

reporting of hand dermatitis and the use of aroma-

therapy products in massage oils, creams, or lotions (OR,

3.27; 95% CI, 1.53-7.02; P=.002) and having a history

of atopic dermatitis (OR, 8.06; 95% CI, 3.39-19.17;

P.001). The risk of allergic contact dermatitis fromes-

sential oils in the occupational setting has been well es-

tablished. Massage therapists should be aware of the sen-

sitizing potential of their oils andthe possibility of personal

andclient adverse skinreactions. Tolower this highpreva-

lence of hand dermatitis in massage therapists, it may be

useful to conduct an educational campaign regarding the

potential hazards of aromatherapy products, the identi-

fication of individuals with atopic background for voca-

tional guidance, and the implementation of proper hand

care practices, such as reduced frequency of hand wash-

ing, avoidance of detergents, and use of protective bar-

rier gloves.

Accepted for publication February 19, 2004.

We thank the following individuals for their contribu-

tions to this work: Boris Lushniak, MD, Paivikki Sus-

itaival, MD, Michael Ming, MD, Joel Gelfand, MD, MSCE,

Donald Belsito, MD, and the dermatology faculty, staff, and

residents at the University of Pennsylvania.

Correspondence: Glen H. Crawford, MD, Department of

Dermatology, 2 Rhoads Pavilion, 3600 Spruce St, Philadel-

phia, PA 19104-4283 (glen.crawford@uphs.upenn.edu).

REFERENCES

1. Burnett CA, Lushniak BD, McCarthy W, Kaufman J. Occupational dermatitis caus-

ing days away from work in US private industry, 1993. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:

568-573.

2. Lushniak BD. The epidemiology of occupational contact dermatitis. Dermatol Clin.

1995;13:671-680.

3. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). National Occu-

pational Research Agenda (NORA). Cincinnati, Ohio: US Dept of Health and Hu-

man Services; 1996. DHHS publication (NIOSH) 96-115.

4. American Massage Therapy Association: Market Analysis (2001). Available at:

www.amtamassage.org. Accessed July 21, 2003.

5. van der Mei IA, de Boer EM, Bruynzeel DP. Contact dermatitis in Alstroemeria

workers. Occup Med (Lond). 1998;48:397-404.

6. Adams RM. Occupational Skin Disease. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1983.

7. Meding B. Epidemiology of hand eczema in an industrial city. Acta Derm Vene-

reol. 1990;153:1-43.

8. Weiss RR, James WD. Allergic contact dermatitis fromaromatherapy. AmJ Con-

tact Derm. 1997;8:250-251.

9. Keane FM, Smith HR, White IR, Rycroft RJ. Occupational allergic contact der-

matitis in two aromatherapists. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43:49-51.

10. Clark SM, Wilkinson SM. Phototoxic contact dermatitis from 5-methoxypsor-

alen in aromatherapy oil. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38:289-290.

11. Cockayne SE, Gawkrodger DJ. Occupational contact dermatitis in an aroma-

therapist. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:306-307.

12. Schaller M, Korting HC. Allergic airborne contact dermatitis from essential oils

used in aromatherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:143-145.

13. Taraska V, Pratt M. Contact dermatitis in massage therapists [abstract]. Am J

Contact Dermatitis. 1997;8:63.

14. Bleasel N, Tate B, Rademaker M. Allergic contact dermatitis following exposure

to essential oils. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:211-213.

15. Bilsland D, Strong A. Allergic contact dermatitis from the essential oil of French

marigold (Tagetes patula) in an aromatherapist. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;23:

55-56.

16. Selvaag E, Holm JO, Thune P. Allergic contact dermatitis in an aroma therapist

with multiple sensitizations to essential oils. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:354-

355.

17. Sugiura M, Hayakawa R, Kato Y, Sugiura K, Hashimoto R. Results of patch test-

ing with lavender oil in Japan. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43:157-160.

18. Tisserand R, Balacs T. The skin. In: Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care

Professionals. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:77-89.

19. Alanko K. Aromatherapists. In: Kanerva L, Elsner P, Wahlberg JE, Maibach HI,

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

995

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

eds. Handbook of Occupational Dermatology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Ver-

lag; 2000:811-813.

20. de Groot AC, Frosch PJ. Adverse reactions to fragrances: a clinical review. Con-

tact Dermatitis. 1997;36:57-86.

21. Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd ed. New

York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000.

22. Flyvholm MA, Susitaival P, Meding B, et al. Nordic occupational skin question-

naireNOSQ-2002: Nordic questionnaire for surveying work-related skin dis-

eases on hands and forearms and relevant exposures. TemaNord. 2002;April:

518.

23. Agrup G. Hand eczema and other hand dermatoses in South Sweden. Acta Derm

Venereol. 1969;49:1-91.

24. Rea JN, Newhouse ML, Halil T. Skin disease in Lambeth: a community study of

prevalence and use of medical care. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976;30:107-114.

25. Smit HA, Coenraads PJ, Lavrijsen AP, Nater JP. Evaluation of a self-

administered questionnaire on hand dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:11-

16.

26. Rycroft RJ. Soluble Oil as a Major Cause of Occupational Dermatitis. Cam-

bridge, England: University of Cambridge; 1982.

27. Coenraads PJ, Nater JP, Van der Lende R. Prevalence of eczema and other der-

matoses of the hands and arms in the Netherlands: association with age and oc-

cupation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:495-503.

28. Susitaival P, Husman L, Hollmen A, Horsmanheimo M, Husman K, Hannuksela

M. Hand eczema in Finnish farmers: a questionnaire-based clinical study. Con-

tact Dermatitis. 1995;32:150-155.

29. Johansen JD, Andersen TF, Veien N, Avnstorp C, Andersen KE, Menne T. Patch

testing with markers of fragrance contact allergy: do clinical tests correspond to

patients self-reported problems? Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:149-153.

30. Bruynzeel DP. Bulb dermatitis: dermatological problems in the flower bulb in-

dustries. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:70-77.

31. Smit HA, Burdorf A, Coenraads PJ. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in different

occupations. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:288-293.

32. Svendsen K, Hilt B. Skin disorders in ships engineers exposed to oils and sol-

vents. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;36:216-220.

33. Meding B, Barregard L. Validity of self-reports of hand eczema. Contact Derma-

titis. 2001;45:99-103.

34. Susitaival P, Husman L, Hollmen A, Horsmanheimo M. Dermatoses determined

in a population of farmers in a questionnaire-based clinical study including meth-

odology validation. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1995;21:30-35.

35. Kavli G, Forde OH. Hand dermatoses in Tromso. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:

174-177.

36. Nilsson E. Individual and environmental risk factors for hand eczema in hospital

workers. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;128:1-63.

37. Lammintausta K. Hand dermatitis in different hospital workers, who performwet

work. Derm Beruf Umwelt. 1983;31:14-19.

38. Susitaival P, Kirk J, Schenker MB. Self-reported hand dermatitis in California vet-

erinarians. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 2001;12:103-108.

39. Tauscher AE, Belsito DV. Frequency and etiology of hand and forearm derma-

toses among veterinarians. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 2002;13:116-124.

40. Pereira F. Hand dermatitis in florists. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:144-145.

41. Sertoli A, Gola M, Martinelli C, et al. Epidemiology of contact dermatitis. Semin

Dermatol. 1989;8:120-126.

42. Livesley EJ, Rushton L, English JS, Williams HC. Clinical examinations to vali-

date self-completion questionnaires: dermatitis in the UK printing industry. Con-

tact Dermatitis. 2002;47:7-13.

43. Vermeulen R, Kromhout H, Bruynzeel DP, de Boer EM. Ascertainment of hand

dermatitis using a symptom-based questionnaire: applicability in an industrial

population. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:202-206.

44. Vermeulen R, Kromhout H, Bruynzeel DP, de Boer EM, Brunekreef B. Dermal ex-

posure, handwashing, and hand dermatitis in the rubber manufacturing indus-

try. Epidemiology. 2001;12:350-354.

45. Kanerva L, Kiilunen M, Jolanki R, Estlander T, Aitio A. Hand dermatitis and al-

lergic patch test reactions caused by nickel in electroplaters. Contact Dermati-

tis. 1997;36:137-140.

46. Berg M, Axelson O. Evaluation of a questionnaire for facial skin complaints re-

lated to work at visual display units. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:71-77.

47. Yngveson M, Svensson A, Isacsson A. Evaluation of a self-reported question-

naire on hand dermatosis in secondary school children. Acta DermVenereol. 1997;

77:455-457.

48. Belsito DV. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Freedberg IM, ed. Fitzpatricks Der-

matology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Co; 2003:

1168-1169.

49. WarshawE, Lee G, Storrs FJ. Hand dermatitis: a reviewof clinical features, thera-

peutic options, and long-termoutcomes. AmJ Contact Dermatitis. 2003;14:119-

137.

50. Cronin E. Clinical patterns of hand eczema in women. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;

13:153.

51. Edman B. Statistical relations between hand eczema and contact allergens. In:

Menne T, Maibach HI, eds. Hand Eczema. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press;

2000:75-83.

52. Rietschel RL, Fowler JF. Fischers Contact Dermatitis. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:270-272.

53. Menne T, Hjorth N. Frictional contact dermatitis. Am J Ind Med. 1985;8:401-

402.

54. Gould WM. Friction dermatitis of the thumbs caused by panty-hose. Arch Der-

matol. 1991;127:1740.

55. Rystedt I. Hand eczema in patients with history of atopic manifestations in child-

hood. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:305-312.

56. Kristensen O. A prospective study of the development of hand eczema in an au-

tomobile manufacturing industry. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:341-345.

57. Susitaival P, Husman L, Horsmanheimo M, Notkola V, Husman K. Prevalence of

hand dermatoses among Finnish farmers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994;

20:206-212.

58. Singgih SI, Lantinga H, Nater JP, Woest TE, Kruyt-Gaspersz JA. Occupational

hand dermatoses in hospital cleaning personnel. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:

14-19.

59. Meding B, Swanbeck G. Prevalence of hand eczema in an industrial city. Br J

Dermatol. 1987;116:627-634.

60. Cardullo AC, Ruszkowski AM, DeLeo VA. Allergic contact dermatitis resulting from

sensitivity to citrus peel, geraniol and citral. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:395-

397.

61. Audicana M, Bernaola G. Occupational contact dermatitis fromcitrus fruits: lemon

essential oils. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:183-185.

62. Brandao FM. Occupational allergy to lavender oil. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;15:

249-250.

63. Romaguera C, Vilaplana J. Occupational contact dermatitis fromylang-ylang oil.

Contact Dermatitis. 2000;33:198-199.

64. Fritz TM, Burg G, Krasovec M. Allergic contact dermatitis to cosmetics contain-

ing Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil) [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;

128:123-126.

65. Dharmagunawardena B, Takwale A, Sanders KJ, Cannan S, Rodger A, Ilchyshyn

A. Gas chromatography: an investigative tool in multiple allergies to essential

oils. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:288-292.

66. van der Valk PG, de Groot AC, Bruynzeel DP, Coenraads PJ, Weijland JW. Aller-

gic contact eczema due to tea tree oil [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1994;

138:823-825.

67. Khanna M, Qasem K, Sasseville D. Allergic contact dermatitis to tea tree oil with

erythema multiforme-like id reaction. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 2000;11:238-

242.

68. Rademaker M. Allergic contact dermatitis fromlavender fragrance in Difflamgel.

Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:58-59.

69. Olumide Y. Contact dermatitis in Nigeria, I: hand dermatitis in women. Contact

Dermatitis. 1987;17:85-88.

70. Kaddu S, Kerl H, Wolf P. Accidental bullous phototoxic reactions to bergamot

aromatherapy oil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:458-461.

71. Rudzki E, Grzywa Z. The value of a mixture of cassia and citronella oils for de-

tection of hypersensitivity of essential oils. DermBeruf Umwelt. 1985;33:59-62.

72. Rudzki E, Grzywa Z. Dermatitis from propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:40-45.

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 140, AUG 2004 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

996

2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on April 15, 2009 www.archdermatol.com Downloaded from

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Effect of Antiseptic Handwashing Vs Alcohol Sanitizer On Health Care-Associated Infections in Neonatal Intensive Care UnitsDokumen7 halamanEffect of Antiseptic Handwashing Vs Alcohol Sanitizer On Health Care-Associated Infections in Neonatal Intensive Care UnitselitamahaputriBelum ada peringkat

- BJD 13441Dokumen53 halamanBJD 13441Remaja IslamBelum ada peringkat

- Occupational Contact Dermatitis in Cleaning Workers Our First ApproachDokumen1 halamanOccupational Contact Dermatitis in Cleaning Workers Our First ApproachAndi Farras WatyBelum ada peringkat

- Mirabelli CD OccuDokumen16 halamanMirabelli CD Occuani putkaradzeBelum ada peringkat

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'3053520368') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Dokumen17 halamanP ('t':'3', 'I':'3053520368') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)alnajBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0190962214012572 MainDokumen17 halaman1 s2.0 S0190962214012572 MainBurcu ÇilBelum ada peringkat

- The Clinical Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Essential Oils and Aromatherapy For The Treatment of Acne Vulgaris - A Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialDokumen7 halamanThe Clinical Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Essential Oils and Aromatherapy For The Treatment of Acne Vulgaris - A Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialreaphenBelum ada peringkat

- A Survey of Occupational SkinDokumen3 halamanA Survey of Occupational SkinLone GhostBelum ada peringkat

- Steroid PaperDokumen16 halamanSteroid PaperkhyatisethiaBelum ada peringkat

- Therapeutic Effect of Melissa Gel and 5% Acyclovir Cream in Recurrent Herpes Labialis: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical TrialDokumen6 halamanTherapeutic Effect of Melissa Gel and 5% Acyclovir Cream in Recurrent Herpes Labialis: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical TrialPutriBelum ada peringkat

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practice On Medication Disposal of Registered Pharmacists in An Academic InstitutionDokumen17 halamanKnowledge, Attitude and Practice On Medication Disposal of Registered Pharmacists in An Academic InstitutionDenise Yanci DemiarBelum ada peringkat

- Adjuvant Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis in Adults by A Herbal Combination: Open German Trial and Review of The LiteratureDokumen5 halamanAdjuvant Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis in Adults by A Herbal Combination: Open German Trial and Review of The LiteratureMini LaksmiBelum ada peringkat

- Consequences of Acne On Stress, Fatigue, Sleep Disorders and Sexual Activity: A Population-Based StudyDokumen4 halamanConsequences of Acne On Stress, Fatigue, Sleep Disorders and Sexual Activity: A Population-Based StudyerinBelum ada peringkat

- Aloe VeraDokumen5 halamanAloe VeraIntense Mutiara RanciaBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review DraftDokumen14 halamanLiterature Review Draftapi-375051320Belum ada peringkat

- Security and Effectiveness Regarding Gamma-Secretase Chemical Nirogacestat (Olaparib) in Desmoid Tumor: Record of Four Pediatric/young Grownup CasesDokumen1 halamanSecurity and Effectiveness Regarding Gamma-Secretase Chemical Nirogacestat (Olaparib) in Desmoid Tumor: Record of Four Pediatric/young Grownup Casesjaguartop90Belum ada peringkat

- Relieving The Pruritus of Atopic Dermatitis: A Meta-AnalysisDokumen7 halamanRelieving The Pruritus of Atopic Dermatitis: A Meta-AnalysisbyronBelum ada peringkat

- A Lean Six Sigma Team Increases Hand Hygiene ComplianceDokumen10 halamanA Lean Six Sigma Team Increases Hand Hygiene Compliancedrustagi100% (1)

- RosaceaDari EverandRosaceaJohn Havens CaryBelum ada peringkat

- Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of DermatologyDokumen19 halamanLookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatologyputri theresia50% (2)

- AJN The American Journal of NursingDokumen21 halamanAJN The American Journal of NursingAzman HariffinBelum ada peringkat

- Augustin 2011Dokumen9 halamanAugustin 2011Trustia RizqandaruBelum ada peringkat

- Dermatologia: Anais Brasileiros deDokumen6 halamanDermatologia: Anais Brasileiros devia_anggraeni15Belum ada peringkat

- Lookingbill and Marksâ Principles of Dermatology (PDFDrive)Dokumen320 halamanLookingbill and Marksâ Principles of Dermatology (PDFDrive)Alexander Hartono100% (5)

- Analytical Chemistry for Assessing Medication AdherenceDari EverandAnalytical Chemistry for Assessing Medication AdherenceBelum ada peringkat

- Prevention and Healing of Skin Wound A Systematic ReviewDokumen13 halamanPrevention and Healing of Skin Wound A Systematic Reviewlongosalyssa930Belum ada peringkat

- Handwashing NSG Research Paper 2022Dokumen7 halamanHandwashing NSG Research Paper 2022Kathy LaminackBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review Hand HygieneDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review Hand Hygienecjxfjjvkg100% (1)

- Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: Clinical ReviewDokumen10 halamanTreatment of Acne Vulgaris: Clinical ReviewAna NunesBelum ada peringkat

- 10 1503@cmaj 092194Dokumen7 halaman10 1503@cmaj 092194هناء همة العلياBelum ada peringkat

- Faktor Perilaku Cuci Tangan Pakai Sabun CTPS Di SMDokumen8 halamanFaktor Perilaku Cuci Tangan Pakai Sabun CTPS Di SMDwi NopriyantoBelum ada peringkat

- PACU-Why Hand Washing Is Vital!: Infection ControlDokumen4 halamanPACU-Why Hand Washing Is Vital!: Infection ControlI Komang BudianaBelum ada peringkat

- Elaziz & Bakr 2008 PDFDokumen12 halamanElaziz & Bakr 2008 PDFRusida LiyaniBelum ada peringkat

- Fast Facts: Dermatological Nursing: A practical guide on career pathwaysDari EverandFast Facts: Dermatological Nursing: A practical guide on career pathwaysBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0197455617300424 MainDokumen9 halaman1 s2.0 S0197455617300424 MainJulia LinzenboldBelum ada peringkat

- Contact Dermatitis - 2023 - Sedeh - Prevalence and Risk Factors For Hand Eczema Among Professional Hospital Cleaners inDokumen9 halamanContact Dermatitis - 2023 - Sedeh - Prevalence and Risk Factors For Hand Eczema Among Professional Hospital Cleaners inani putkaradzeBelum ada peringkat

- Chemicals, Cancer, and Choices: Risk Reduction Through MarketsDari EverandChemicals, Cancer, and Choices: Risk Reduction Through MarketsBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Skripsi 4Dokumen4 halamanJurnal Skripsi 4dezunBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines of Care For The Management of Atopic DermatitisDokumen16 halamanGuidelines of Care For The Management of Atopic DermatitisJuliana SusantioBelum ada peringkat

- PAYUSAN, Angela Mae M. - BSPSY 3-5Dokumen3 halamanPAYUSAN, Angela Mae M. - BSPSY 3-5Angela PayusanBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper - FinalDokumen16 halamanResearch Paper - Finalapi-455663099Belum ada peringkat

- Vis Cher PaperDokumen11 halamanVis Cher PaperAndi Prajanita AlisyahbanaBelum ada peringkat

- Research PaperDokumen10 halamanResearch Paperapi-345759649Belum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Nila Indria U. 09711110Dokumen11 halamanJurnal Nila Indria U. 09711110Nila Indria UtamiBelum ada peringkat

- Melasma Treatment: An Evidence Based Review: Jacqueline Mckesey Andrea Tovar Garza Amit G. PandyaDokumen53 halamanMelasma Treatment: An Evidence Based Review: Jacqueline Mckesey Andrea Tovar Garza Amit G. PandyaStella SunurBelum ada peringkat

- Integrative Dermatology: Practical Applications in Acne and RosaceaDari EverandIntegrative Dermatology: Practical Applications in Acne and RosaceaReena N. RupaniBelum ada peringkat

- Delayed Inflammatory Reactions To Hyaluronic Acid 2020Dokumen8 halamanDelayed Inflammatory Reactions To Hyaluronic Acid 2020maat1Belum ada peringkat

- The Problem and Its Setting: "Hand Washing Is Associated With Voluntary Individualistic Behavior." Dean David HolyoakeDokumen3 halamanThe Problem and Its Setting: "Hand Washing Is Associated With Voluntary Individualistic Behavior." Dean David HolyoakeKathleen Camille ManiagoBelum ada peringkat

- Aromatherapy: A Systematic Review: MethodDokumen4 halamanAromatherapy: A Systematic Review: MethodDeesha MajithiaBelum ada peringkat

- Health Revision SheetDokumen11 halamanHealth Revision Sheetapi-317980894100% (1)

- DST 8013Dokumen4 halamanDST 8013FelpScholzBelum ada peringkat

- Cancer Health Effects of Pesticides - The College of Family Physicians of CanadaDokumen11 halamanCancer Health Effects of Pesticides - The College of Family Physicians of CanadaKashaf ButtBelum ada peringkat

- Intervention Development in Occupational ResearchDokumen7 halamanIntervention Development in Occupational ResearchAllisa DzakwanBelum ada peringkat

- Ethics and Professionalism 2016: C. Ronald Mackenzie, MDDokumen8 halamanEthics and Professionalism 2016: C. Ronald Mackenzie, MDjafralizBelum ada peringkat

- Burnout PDFDokumen8 halamanBurnout PDFSalvatore Verlezza ArmenioBelum ada peringkat

- Acne TreatmentDokumen6 halamanAcne TreatmentTry Febriani SiregarBelum ada peringkat

- Users' Guides To The Medical Literature XIVDokumen5 halamanUsers' Guides To The Medical Literature XIVFernandoFelixHernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Cancer: Review of Applications and FindingsDokumen27 halamanAcceptance and Commitment Therapy in Cancer: Review of Applications and FindingsJuan Alberto GonzálezBelum ada peringkat

- Bodeker, Wellness, Spas DR GERARDDokumen36 halamanBodeker, Wellness, Spas DR GERARDNorliza OthmanBelum ada peringkat

- Application Form For The Registration of Importers & ExportersDokumen4 halamanApplication Form For The Registration of Importers & ExportersNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Bsava Protect PosterDokumen1 halamanBsava Protect PosterNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Bajaj Pulsar Discover - XLSX 0Dokumen9 halamanBajaj Pulsar Discover - XLSX 0Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Series Centrifugal Pump With Flanged Connection: LimitsDokumen5 halamanSeries Centrifugal Pump With Flanged Connection: LimitsNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDokumen23 halamanEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Terms & Conditions For Lounge Access and Excess Baggage ( )Dokumen2 halamanTerms & Conditions For Lounge Access and Excess Baggage ( )Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Importers Drugs1 2016Dokumen2 halamanImporters Drugs1 2016Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Matrix Magic SquaresDokumen31 halamanMatrix Magic SquaresNilamdeen Mohamed Zamil100% (1)

- Antibiotics PDFDokumen4 halamanAntibiotics PDFNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Magic Squares, Continued: V. Using One of The Magic Squares You Created Using Digits (0-8), Perform The FollowingDokumen3 halamanMagic Squares, Continued: V. Using One of The Magic Squares You Created Using Digits (0-8), Perform The FollowingNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Automatic Self-Priming Pump With Brass Impeller CoverDokumen4 halamanAutomatic Self-Priming Pump With Brass Impeller CoverNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- General Conditions of Sale Relating To Internet Sales by Pipa To ConsumersDokumen8 halamanGeneral Conditions of Sale Relating To Internet Sales by Pipa To ConsumersNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Burg GraffDokumen2 halamanBurg GraffNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- 1119827169eijerkamp and Heremans-CeustersDokumen4 halaman1119827169eijerkamp and Heremans-CeustersNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Our Lord! Send Salutations Upon Muhammad, The Untaught Prophet, Upon His Family and Send (Continuous) Peace.Dokumen1 halamanOur Lord! Send Salutations Upon Muhammad, The Untaught Prophet, Upon His Family and Send (Continuous) Peace.Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Folder 2009 JosDokumen1 halamanFolder 2009 JosNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- LDteamDokumen1 halamanLDteamNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Product List VetDokumen6 halamanProduct List VetNilamdeen Mohamed Zamil100% (2)

- Du$27as For The ToiletDokumen1 halamanDu$27as For The ToiletNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Olympic 2008 Part 2Dokumen1 halamanOlympic 2008 Part 2Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Etiquette Before SleepingDokumen1 halamanEtiquette Before SleepingNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Her Bots 2008Dokumen1 halamanHer Bots 2008Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Product List Vet PDFDokumen6 halamanProduct List Vet PDFNilamdeen Mohamed Zamil75% (4)

- By Ehsan Khazeni, Iran: Admin@tashtar - IrDokumen7 halamanBy Ehsan Khazeni, Iran: Admin@tashtar - IrNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- By Ehsan Khazeni, Iran: Admin@tashtar - IrDokumen7 halamanBy Ehsan Khazeni, Iran: Admin@tashtar - IrNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- CatalogDokumen18 halamanCatalogNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- "Our Lord!: Sit and Drink With The Right Hand Animals Standing and DrinkingDokumen1 halaman"Our Lord!: Sit and Drink With The Right Hand Animals Standing and DrinkingNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- When Leaving The HomeDokumen1 halamanWhen Leaving The HomeNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Marcel SangersDokumen20 halamanMarcel SangersNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Enabling Arabic Input: Yping in Rabic IndowsDokumen6 halamanEnabling Arabic Input: Yping in Rabic IndowsNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilBelum ada peringkat

- Soft Touch EnterprisesDokumen19 halamanSoft Touch EnterpriseskishoreBelum ada peringkat

- Addressing Dry Skin, Acne, Pigmentation & WrinklesDokumen26 halamanAddressing Dry Skin, Acne, Pigmentation & WrinklesMucharla Praveen KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Exceptional Variant of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Psoriasiform PresentationDokumen2 halamanExceptional Variant of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Psoriasiform PresentationasclepiuspdfsBelum ada peringkat

- MY SPEECH - Persuasive SpeechDokumen2 halamanMY SPEECH - Persuasive SpeechFitriBelum ada peringkat

- List of Illegal Products Found 2014 ONE PAGERDokumen1 halamanList of Illegal Products Found 2014 ONE PAGERAkash GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Laikou FBDDokumen2 halamanLaikou FBDFarhanas Unique CollectionBelum ada peringkat

- Ethnobotany of Arghakhanchi District Nepal Plants PDFDokumen7 halamanEthnobotany of Arghakhanchi District Nepal Plants PDFkp pokharelBelum ada peringkat

- Inventario de ProductosDokumen66 halamanInventario de ProductosJHON YERY CORIPUNA SEGOVIABelum ada peringkat

- Somethinc-Jakartaxbeauty2023 (Booth XL) (21.12)Dokumen16 halamanSomethinc-Jakartaxbeauty2023 (Booth XL) (21.12)ARIF WIDIANTORO 211212138Belum ada peringkat

- Guidelines On Aesthetic Medical Practice - 110613Dokumen47 halamanGuidelines On Aesthetic Medical Practice - 110613windows3123Belum ada peringkat

- DERMATOMYCOSISDokumen114 halamanDERMATOMYCOSISQonita Qurrota AyunBelum ada peringkat

- UPDATE 2021: Cosmetic DermatologyDokumen20 halamanUPDATE 2021: Cosmetic DermatologyFitta PutriBelum ada peringkat

- Anti Fungal Products UpdatedDokumen36 halamanAnti Fungal Products Updatedsonuhemant33Belum ada peringkat

- Pyoderma-NonPyoderma DR - Danny PDFDokumen89 halamanPyoderma-NonPyoderma DR - Danny PDFPrayogaTantraBelum ada peringkat

- Acquired Hyperpigmentation Disorders - UpToDateDokumen106 halamanAcquired Hyperpigmentation Disorders - UpToDateRene GuevaraBelum ada peringkat

- Katalog TreatmentDokumen12 halamanKatalog TreatmentSri Suharti RSHBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Report of A Morphea in A 19 Years Old FemaleDokumen2 halamanA Case Report of A Morphea in A 19 Years Old FemaleInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Berita Resmi Merek Seri-A: No. 16/P-M/III/A/2022Dokumen483 halamanBerita Resmi Merek Seri-A: No. 16/P-M/III/A/2022HasriABelum ada peringkat

- Contact Dermatitis: What Are Some Common Causes of Contact Dermatitis?Dokumen13 halamanContact Dermatitis: What Are Some Common Causes of Contact Dermatitis?Hanna AthirahBelum ada peringkat

- Chemical PeelDokumen64 halamanChemical PeelDrAmit Gaba MdsBelum ada peringkat

- Cos - Chapter 8 Skin DisordersDokumen7 halamanCos - Chapter 8 Skin DisordersALIBelum ada peringkat

- Reten Modern Dressing 2023 PKDMTDokumen51 halamanReten Modern Dressing 2023 PKDMTMasros TukiranBelum ada peringkat

- BRG DGDokumen158 halamanBRG DGAdji SuryaBelum ada peringkat

- A CASE of Acne VulgarisDokumen4 halamanA CASE of Acne VulgarisHomoeopathic Pulse100% (1)

- Lesson One Hospital DepartmentDokumen4 halamanLesson One Hospital DepartmentIkhsan QusayBelum ada peringkat

- Derma NotesDokumen36 halamanDerma NotesMaya TolentinoBelum ada peringkat

- PressureUlcer GradingToolDokumen1 halamanPressureUlcer GradingToolAbbas AlkamelBelum ada peringkat

- Skin Care ClassDokumen16 halamanSkin Care ClassMuhammad Aliff Abdul RahmanBelum ada peringkat

- Beautylish The Ordinary Treatment Guide 1 - PDFDokumen2 halamanBeautylish The Ordinary Treatment Guide 1 - PDFarinilhaque25% (4)

- Common Skin DiseasesDokumen35 halamanCommon Skin DiseasesNoman MunirBelum ada peringkat