An Interview With Sensorband: Bert Bongers

Diunggah oleh

Trisha JacksonDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

An Interview With Sensorband: Bert Bongers

Diunggah oleh

Trisha JacksonHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ber 1993, at the Son Image festival in Berlin.

While

in Berlin, Edwin had the idea to form a trio. Sen-

sorbands rst performance was in December of

1993, at Voyages Virtuels, a virtual reality exhibit

organized by Les Virtualistes in Paris.

I interviewed Sensorband in The Hague in No-

vember 1996, and thereafter the discussion was ex-

tended through electronic mail. The topics of the

interview included: how they established an en-

semble based entirely on new electronic instru-

ments; the special musical and technical concerns

associated with the medium; their aesthetic views

on the relationship between science and art; and

their inuences and approaches. Before presenting

the interview, however, I will start with some ex-

planatory notes about the musicians and their

unique instruments.

Background

The Performers

Zbigniew Karkowski (see Figure 1) was born in

1958 in Krakow, Poland. Zbigniew studied composi-

tion at the State College of Music in Gothenburg,

Sweden, aesthetics of modern music at the Univer-

sity of Gothenburgs Department of Musicology,

and computer music at the Chalmers University of

Technology. After completing his studies in Swe-

den, he studied sonology for a year at the Royal

Conservatory of Music in Den Haag, Netherlands.

During his education, he also attended many sum-

mer composition master courses arranged by Cen-

tre Acanthes in Avignon and Aix-en-Provence,

France, studying with Iannis Xenakis, Olivier Mes-

siaen, Pierre Boulez, and Georges Aperghis, among

others.

Zbigniew works actively as a composer of both

acoustic music and electroacoustic computer mu-

sic. He has written two pieces for large orchestra,

Bert Bongers

An Interview with

Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten

Sarphatistraat 470

Sensorband

1018 GW, Amsterdam, Netherlands

bertbon@xs4all.nl

Sensorband, as the name suggests, is an ensemble

of musicians who use sensor-based gestural control-

lers to produce computer music. Gestural inter-

facesultrasound, infrared, and bioelectric sen-

sorsbecome musical instruments. The trio

consists of Edwin van der Heide, Zbigniew Karkow-

ski, and Atau Tanaka, each a soloist on his instru-

ment for over ve years. Edwin plays the MIDI-

Conductor, a pair of machines worn on his hands.

The MIDI-Conductor uses ultrasound signals to

measure his hands relative distance, along with

mercury tilt sensors to measure their rotational ori-

entation. Zbigniew activates his instrument by

moving his arms in the space around him. This mo-

tion cuts through invisible infrared beams mounted

on a scaffolding structure. Atau plays the BioMuse,

a system that tracks neural signals, translating elec-

trical signals from the body into digital data. To

quote the groups World Wide Web page (http://

zeep.com/sensorband), the result is a powerful mu-

sical force of intense percussive rhythms, deep puls-

ing drones, and wailing melodic fragments.

As a developer of new electronic musical instru-

ments, I have been involved in some of Sensor-

bands projects, and have seen the group perform a

number of times, starting in 1994 at the Sonic Acts

Festival in Paradiso, Amsterdam. At these concerts,

the audience becomes involved in the compelling

energy of the performance, the relationship be-

tween physical gesture and sound, and the musical

communication between the three performers. A

Sensorband concert is impressive in its display of in-

strumental virtuosity, and proves that the three mu-

sicians have been playing together for some time.

Although they had met each other individually

on several occasions (including the International

Computer Music Conference in Cologne in 1988),

the rst time the three met as a group was in Octo-

13 Bongers

Computer Music Journal, 22:1, pp. 1324, Spring 1998

1998 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

both of which were commissioned and performed

by the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, plus an

opera and several chamber music pieces that were

performed by professional ensembles in Sweden, Po-

land, and Germany.

Atau Tanaka (see Figure 2) was born in Tokyo

and educated in the USA. He studied electronic mu-

sic at Harvard University under Ivan Tcherepnin,

composition and recording engineering at the Pea-

body Conservatory, and computer music at Stan-

ford Universitys Center for Computer Research in

Music and Acoustics (CCRMA). While at Stanford,

he was asked to compose the rst concert piece for

BioMuse, a bioelectrical musical instrument (de-

scribed below).

In 1992, during his studies at CCRMA, Atau was

awarded a residency at the Stanford atelier in the

Figure 1. Zbigniew Kar-

kowski performs virtual

percussion in a cage

that is armed with infra-

red beams. (Photo by Peter

Kers.)

Cite

des Arts in Paris, and conducted research at In-

stitut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/

Musique (IRCAM). Enticed by the rich musical cul-

ture in Europe, he stayed on, settling in Paris for

ve years. During this time, he concertized with

the BioMuse, and continued his work with sensor

technology, often working in residency at Stichting

Elektro-Instrumentale Muzeik (STEIM) in Amster-

dam. In 1995, he became Artistic Ambassador for

Apple France for his work using interactive techno-

logies for music. During this time, his work in-

cluded solo sound/image performances, telematic

concerts, interactive media pieces, group perfor-

mances in the French improvised-music scene, and

the creation of Sensorband. He is currently living

in Tokyo, pursuing network, noise, orchestral, and

recorded-music projects.

14 Computer Music Journal

pect was to build an environment where the perfor-

mer on stage can act both as a composer and con-

ductor without being attached to wires or any other

contraptions.

The system provides the performer with real-

time control over parameters such as velocity/dy-

namics, tempo, and articulation, as well as control

of the formal structure of the music, mainly

through Max.

Atau Tanakas instrument, the BioMuse, is a bio-

signal musical interface developed by Hugh Lusted

and Ben Knapp of BioControl Systems (Knapp and

Lusted 1990; Lusted and Knapp 1996). The Bio-

Muse was developed at Stanford Universitys

CCRMA in conjunction with the Medical School

and the Electrical Engineering Department. The

original intent was to create a musical instrument

driven by bioelectrical signals from the brain, skele-

tal muscles, and eyeballs. The BioMuse is also used

in applications of eye tracking and brain-wave analy-

sis, in work with the physically challenged, and in

telemedecine. It uses electroencephalogram, electro-

myogram (EMG), and electrooculogram signals, and

translates these analog bioelectrical signals into

MIDI and serial digital data.

Ataus musical work with the BioMuse uses the

BioMuses four EMG channels. Each input channel

receives a signal from a differential gel electrode

triplet. Armbands with these electrodes are worn

on the inner and outer forearm, tricep, and bicep.

These signals are ltered and analyzed by the digi-

tal signal processor (DSP) on-board the BioMuse,

and converted to MIDI controller data as output. In

perform time stretching on

digitally sampled vocal

sources. (Photo by Peter

Kers.)

Figure 3. Edwin van der

Heide works with the

MIDI-Conductor, an

ultrasound-based spatial

hand-held instrument, to

Figure 2. Atau Tanaka uses

muscle signals and ges-

tures to play the BioMuse

instrument. (Photo by Pe-

ter Kers.)

Edwin van der Heide (see Figure 3) studied music

technology at the Utrecht School of the Arts, and

sonology at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague,

where he graduated in 1992. Since then, Edwin has

been working as a solo performer and has been ac-

tive in several collaborations and groups, including

Sensorband, Loos, and Theatregroup Hollandia.

Recently, Edwin collaborated with Victor Wen-

tink at the Delta Works in Holland on a permanent

sound installation featuring over 60 loudspeakers,

commissioned by the Dutch government. Since

1995, Edwin has taught sound design at the Inter-

faculty Sound and Image at the Royal Conservatory

and the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague.

The Instruments

Zbigniew Karkowskis instrument is a system of

32 infrared sensors mounted in velocity-sensitive

pairs: 16 sensors are transmitters, and 16 are detec-

tors. These sensors scan the position of the arms

and the velocity of their movement. Voltage data

from these sensors is translated into MIDI by Vladi-

mir Grafovs custom-built scanner. From there the

data is sent to Opcodes Max software (the struc-

tural brain of the system), and to Digidesigns

Sample Cell II, which is the orchestra.

This system was developed by Zbigniew and Ulf

Bilting in Sweden in 1990. The rst performance

with it took place at STEIM in February, 1990. Zbig-

niews initial idea was to be able to play music by

just moving his arms in the air. The important as-

15 Bongers

Ataus stage setup, the resulting data is routed to a

laptop computer running Max. Max patches cre-

ated by Atau transform the control data so that it

can enter a compositional framework, and then be

dispatched to MIDI synthesizers and real-time

computer-graphics performance software.

Edwin van der Heides instrument consists of

two elements: the controller part and the sound

synthesis part. The controller is called the MIDI-

Conductor. A small series of these controllers was

developed and built by the interviewer in a joint

project of the Institute of Sonology and STEIM, un-

der the supervision of Michel Waisvisz, and mod-

eled after Michels instrument, the Hands (Krefeld

Figure 4. Members of Sen-

sorband perform on the

Soundnet.

1990). (There is an active collaboration between

STEIM and the Royal Conservatory; both play im-

portant roles in developing new instruments.

For more information, on the World Wide Web

see http://www.xs4all.nl/~steim and http://

www.koncon.nl/220/SOmain.html.)

Edwins small, hand-held instrument has ultra-

sound sensors (for measuring the distance between

both hands), a pressure sensor, two tilt sensors, a

movement sensor, and a number of switches. All of

these sensors are connected to the STEIM Sensor-

Lab, an embedded, programmable microcontroller

that translates the signals into MIDI data.

For sound synthesis, Edwin uses a personal com-

16 Computer Music Journal

is modest compared to the physical aspect. The

rope, the metal, and the humans climbing on it re-

quire intense physicality, and focus attention on

the human side of the human-machine interaction,

not on mechanistic aspects such as interrupts,

mouse clicks, and screen redraws. Sensorband has

chosen to work with digital recordings of natural

sounds. The signals from Soundnet control DSPs

that process the sound through ltering, convolu-

tion, and waveshaping. Natural, organic elements

are thus put in direct confrontation with technol-

ogy. The physical nature of movement meeting the

virtual nature of the signal processing creates a

dynamic situation that directly addresses sound as

the fundamental musical material. Through ges-

ture and pure exertion, the performers sculpt raw

samples to create sonorities emanating from the

huge net.

The Soundnets immense size introduces an enor-

mous challenge of instrumental virtuosity. Al-

though innovative MIDI instruments are often

called controllers, with Soundnet, the notion of

control is called completely into question: the in-

strument is too large for humans to thoroughly

master. The ropes create a physical network of in-

terdependent connections, so that no single sensor

can be moved in a predictable way that is indepen-

dent of the others. It is a multi-user instrument

where each performer is at the mercy of the others

actions. In this way, the conict of control versus

uncontrollability becomes a central conceptual fo-

cus of Soundnet.

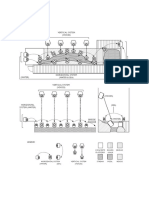

Figure 5. The Soundnet

sensor.

puter with an Ariel DSP-96 board. This board con-

tains a Motorola 96000 oating-point DSP. Edwin

developed the software. Algorithms such as real-

time phase vocoding, oscillating harmonizers, and

room simulation with Doppler-shift effect are used

along with hard-disk recording and playback in a

live concert environment. Besides the DSP, Edwin

recently started to use Supercollider on the Apple

Macintosh for real-time granular synthesis and cha-

otic looping of samples.

In addition to playing their individual instru-

ments, the Sensorband musicians also perform to-

gether on Soundnet, an architectural musical instru-

ment of monumental proportions (see Figure 4

and the front cover). It is a giant web, measuring

11 11 m, strung with 16-mm-thick shipping

rope. At the end of the ropes, there are eleven sen-

sors that detect stretching and movement. The

three Sensorband musicians perform on the instru-

ment by climbing it. Soundnet was commissioned

by the festivals Visas and Exit in Paris, where it was

rst performed upon in April 1996. It was then per-

formed upon at the Dutch Electronic Arts Festival,

organized by the V2 Organization in Rotterdam.

Soundnet was inspired by the Web, a spider

web 1 m in diameter that was created by Michel

Waisvisz at STEIM and the Institute of Sonology.

The idea with Soundnet was to scale the Web to a

size proportional to human spiders. The sensors

(see Figure 5) were designed by the interviewer and

fabricated by Theo Borsboom, a Harley-Davidson

mechanic. The sensors are located inside each cylin-

der, with a spring and piston that can sustain 500

kg of weight. The large spring resembles a motorcy-

cles shock absorber. Inside the cylinder is a large

fader (potentiometer). As the performers climb the

ropes, the sensors stretch and move in response to

their movements. This displaces the faders inside,

sending a variable-voltage control signal to the

iCube, which is the computer interface box. (For in-

formation about the Infusion Systems iCube, see

the World Wide Web site at http://www.

infusionsystems.com.) The iCube sends a MIDI

signal to a Macintosh that is running the Max

software.

Soundnet is a musical instrument using inter-

active technology; however, the technology aspect

17 Bongers

Musical Roles in Sensorband

Bongers: With the kind of technology you are us-

ing, it is possible to play each others parts and con-

trol each others sounds. Can you describe your

roles in the group?

van der Heide: Each musicians sound depends on

the type of sensors he uses. For instance, Zbig-

niews sensors are triggers, so he plays more percus-

sive sounds. Atau and I both play more with timbre

and sound color. It is one of the secrets of why Sen-

sorband works so well.

Tanaka: The fact that we settled on these instru-

ments is an important part of what we do. There is

a common gesture-based element among these

three instruments. However, since each instrument

works with a different kind of sensor, each serves a

different function in the ensemble. The music

would change if the instruments were different.

van der Heide: As with any genre, the combination

of instruments, and the sound sources attached to

them, help dene the ensemble. For example, with

a string trio, there are string instruments. . . . But I

would not be able to play Zbigniews part well.

Karkowski: It would sound different. Nevertheless,

the important thing is that there is always the pos-

sibility that we can play each others instruments.

Tanaka: The three instruments sometimes take on

separate roles, sometimes start to blend together,

sometimes confuse each other and then go apart

again.

Karkowski: In a way, the only thing that denes

our different roles are the limitations of our instru-

ments. This is one of the only traditional aspects of

the group.

Bongers: Have you ever considered adding a fourth

member to the band?

Karkowski: We have not thought about it, but we

are open to collaboration.

van der Heide: We have just realized a project,

Xtended Thrill, in collaboration with Granular Syn-

thesis at InterCommunication Center (ICC ) of Japa-

nese Telecom in Tokyo.

Karkowski: We also performed with percussionist

Paul Koekat DasArts in Amsterdam in 1996.

Tanaka: The performance we did with Paul was ex-

citing for usSensorband plus a guest. The trio

acts as a good core unit, because the idea of three

sensor instruments is a simple and straightforward

concept. Three is a good number. In a trio, the in-

struments can be either solo or accompaniment,

virtuosic or egalitarian. It has always been a strong

ensemble in other musical genres, whether it is

string trio, jazz trio, or power trio.

van der Heide: The trio is the smallest ensemble

with which you can create all the musical forms.

Karkowski: There were many groups in the history

of popular music that consisted of soloists playing

togetherfor example, Cream, the seminal virtu-

oso rock power trio of the late 1960s (Eric Clapton,

Jack Bruce, and Ginger Baker).

Tanaka: In Sensorband, we each bring the sounds

of our solo performances to the group, so the prob-

lem often can be that the texture is too thick when

we are all playing at once.

Karkowski: We used to all play at once all the

time! [All laugh.]

van der Heide: There are still many forms of this

trio that we have not explored yet. The rst time

where we really started working with duos against

duos, to form duos inside the trio, was at the con-

cert in November 1996 in Krakow, Poland at the

Audio Arts Festival.

Bongers: Does the audience experience you as a

group or as individual soloists?

van der Heide: The presentation is a band presen-

tation.

Karkowski: We are a band, because we perform as

an ensemble. [See Figure 6.]

van der Heide: We never give solo performances on

the same concert.

Karkowski: [laughs] Only very long solos!

Tanaka: Because of our musical roles during perfor-

mance, the audience perceives us as a group. There

is a mass of computer-generated electronic sound

coming from three musicians on stage. The audi-

ence must distinguish who is playing what. At

some moments it is clear, and there are other mo-

ments where it is unclear. We can play with this

ambiguity. It is a kind of natural reaction on the

part of the audience to try to make a connection be-

tween the physical gesture they see and what they

hear. However, to do so is difcult, because these

sounds are unknown. These are abstract computer-

18 Computer Music Journal

for a number of years. I have hardly changed my

sounds in the last ve years. [Edwin laughs loudly.]

Tanaka: This is an important point, because we are

dealing with a technological eld where some

people change machines every year. But each of us

has been working with technology-based instru-

ments to sustain the relationship with the machine

for a longer time. One has to stay with a violin for

20 years to begin to really master it. The issues

with these new kinds of instruments is that there

is no performance-practice history; it is based on

technology that ips and changes every year. For

me, it was interesting with the BioMuse to nd an

instrument I could stick with for some time and ex-

plore it in depth. It is different from the way most

Figure 6. Sensorband in

concert.

generated sounds, whereas with acoustic ensemble

music there is always some prior knowledge of how

the individual instruments sound.

Bongers: I can imagine that it is important to de-

ne your boundaries, to limit your playing in perfor-

mance. Perhaps the danger with all this technology

is that the musical possibilities are limitless and

variable. How do you cope with this compositional

problem?

Karkowski: The most important problem is the

danger of confusing yourself as the performer.

When one performs something for a long time it

feels like a part of him. When he tries something

new, it can feel foreign. The strength of the group is

that we have been working with certain technology

19 Bongers

people deal with this kind of technology in the arts

. . .they wait for the new machine to come out next

year, and when they get it, they have to start all

over again. Our approach has many ties to tradi-

tional instrumental music in this way.

van der Heide: Although I am still working on 3-D

sound and a better system, I came back to using

the MIDI-Conductor again, which I have been us-

ing for more than six years now. I am feeling more

and more comfortable with it, and at the same

time, I am becoming much more responsive and

musical in playing the instrument in the ensemble.

Karkowski: I recently watched an interview with

Pierre Boulez on French television, where he men-

tioned that there always will be a difference be-

tween computer music and traditional instrumen-

tal music, because musicians can perform (or

interpret) gestures, and computers cannot. We

think that is the previous generations view on com-

puters. One of the most important goals for us is to

make gestural music performances with com-

puters.

van der Heide: Every medium has its own quali-

ties. A recording will never sound the same as a

live concert, because the recording plays exactly

the same thing twice, which you never can do in a

live performance. On the other hand, you could

also compose especially for this recorded medium.

So, each medium has its own advantages for the

composer.

Karkowski: This is obvious. The whole movement

of punk rock illustrated this in a clear way. Live per-

formance is mainly about attitude and presenceit

can even be more important than what is created. I

am convinced that the performers attitude and en-

ergy on stage is more important than the sound

coming from the speakers. And, of course, in the re-

corded media, this aspect is eliminated.

Tanaka: I like Edwins idea that certain media can

exploit certain musical gestures, because it relates

to the earlier notion of idiomatic instrumental

writing.

Karkowski: The computer is an instrument, but it

is actually a tool as well. If one uses an instru-

mentsay, a violin or guitarin a non-idiomatic

way; for instance, if one plays the violin with a

chain saw or drill machine, then it is not only an in-

strument in the traditional sense, but also a new

tool to make sound.

van der Heide: Yes, but not just another tool. It is

more, because using a computer in live perfor-

mance is an artistic choice. There is much to gain

by using a particular medium. This decision re-

ects the interest and artistic choices of the per-

former.

Tanaka: A performer begins by highlighting charac-

teristics of a certain tool or a technology for inter-

esting artistic use, by featuring its capabilities, as

well as its limitations. The word tool implies

something utilitarian, something more generalist.

With a tool, there is the hope that it will become

better at its job, and will perhaps someday do every-

thing. With an instrument, on the other hand, the

performer accepts its limitations, and in fact, cele-

brates them, taking into account the instruments

personality.

The problem with computers is that they are gen-

eralist devices. Here we are, on stage, with the

same computers that people use to keep their -

nances. So I make a choice of software, a choice of

the way I work with the computer, and this starts

to dene my instrument.

van der Heide: If one uses score- or note-generating

programs, the question becomes whether the music

theyre making is theirsor is it the music from

the program?

Tanaka: But then, a piece of software can take on a

kind of personality, like an instrument. Dissimilar-

sounding music made with a certain program can

sound similar. Although this is often criticized,

maybe it is not such a bad thingperhaps the pro-

gram can have an interesting musical personality of

its own?

Network Concerts

Bongers: In addition to the computer instruments,

another medium that you have been experimenting

and performing with is the network concert, where

each of you perform live from totally different geo-

graphical locations. Can you describe how this

started, and how you deal with the specic compo-

sitional or logistical problems you encounter? Is it

20 Computer Music Journal

New York, processed by me, and sent back to Paris.

When we practiced this piece in Paris before the

concert, we rehearsed it using a digital-delay simu-

lation. When we perform using ISDN, we do not

want to make the performance as accurate as pos-

sible in the traditional sense, but as different as pos-

sible. It is a completely different medium.

Karkowski: For example, during our residency in

Canada in August 1996 (at Obscure, part of the

Meduse arts center in Quebec City), we presented

an ISDN concert using the system in a nonstandard

way. It was interesting to do only two things with

itthe exact things that others try to avoid

namely, feedback and delay.

van der Heide: One of the interesting applications

with network technology is to retransmit the pro-

jection from a signal coming from one space back

to that same space, as a kind of feedback. Distance

is one of the important issues in using ISDN. Dis-

tance becomes one of the issues of the compo-

sition.

Karkowski: Another artistic aspect with ISDN con-

certs is the idea of control. Very often, composers

use computers to achieve greater control. We have

found, after playing several concerts like this, that

we could never control the output 100 percent. As-

pects like the delay become unknown variables,

which is interesting.

Tanaka: As artists, our rst instinct is not to make

technical improvements to the system, but rather,

to manipulate the technology in a creative manner.

The technical limitations become characteristics of

the composition. Doing this allows us not to be so

worried about transmission delay, rather, to be con-

cerned about the general notion of distance. We

bring the element of distance to a concert, which,

as Zbigniew said, we sometimes have difculty con-

trolling.

Karkowski: Instead of merely using technology, we

try to do something truly musical with it . . . the

audience feels the passion.

Tanaka: Yes, I have had many reactions from

people about emotion or the passion of the musical

communication that we attempt to maintain

through the distance. In fact, a different result is

heard in each of the three locations, which is com-

pelling.

also for convenience, when one of the band mem-

bers cannot be there, or is it for artistic reasons?

Tanaka: In our ISDN [Integrated Services Digital

Newtork] concerts, we use videoconferencing tech-

nology to perform a live concert. This network tech-

nology consists of a certain audio quality which is

not CD quality, a certain video quality which

makes the image look like it is coming from the

moon, and time delay. When other musicians are

confronted with the system, the rst thing they re-

quest is to eliminate the time delay. But we feel

that it is a characteristic of this system, and con-

sider this transmission medium, video conferenc-

ing, as part of our extended instrument. A Sen-

sorband concert for ISDN is different from

Sensorband live. We never use it to compensate for

a missing member, it has never been for replace-

ment. We try to distinguish that clearly.

As you mentioned, the performance situation is

an ensemble where one musician is local but the

other musicians are distant. Therefore, the audi-

ence is more separated from the musicians who are

projected on video screens. But somehow, due to

the mode of communication, or the medium that is

used, the audience relates to the contact dynamic

between the local musician and the musicians per-

forming on the video, engaging with these distant

performers. The fact that this human interaction

takes place through these severely compromised

conditions raises the audiences awareness to prob-

lems like trying to keep eye contact, or trying to re-

spond to each other using the delay, or in spite of

the delay. The nice surprise is that the audience

joins us in a natural way.

van der Heide: The rst concert with ISDN was a

concert where Atau and I were in New York per-

forming with Camel Zekri, an acoustic guitarist,

who was in Paris, and both spaces already had

ISDN connections. This was not a Sensorband per-

formance. This piece of mine was written as a local

piece for guitar and MIDI-Conductor. It also

worked well over ISDN, because there was heavy in-

teraction between me and the guitar player as I pro-

cessed his sounds and sent them back. In the

places where his acoustic sound was not amplied,

the only sound that was audible was the processed

sound from his guitar. These sounds were sent to

21 Bongers

Japan and the Relationship Between Art and

Science

Bongers: You are now involved in the Japanese art

scene. Is it different from the situation in Europe or

the USA?

Tanaka: In Europe, the composers function is re-

spected to a certain degree, but at the same time

the use of technology challenges this role. That is

why Japan is an interesting place right now, be-

cause art in a non-occidental culture has had a dif-

ferent sociological role. The notion of high art is a

Western European notion. This is a system that has

been imposed on artistic expression and production

worldwide. Conversely, in Japan, art is tied to crafts-

manship. Even though Japanese culture has success-

fully assimilated the Western way, Japan keeps its

cultural traditions of thousands of years, where an

artist was more of a craftsman. This living history

combined with the arrival of technology puts Ja-

pans culture at an interesting crossroads now.

van der Heide: In Europe, art and science are often

separated, whereas Japan is one of the few coun-

tries where art and science are more integrated.

The link between art and technology is important.

A couple of centuries ago, art and science belonged

together, where as today, scientists are often taken

seriously only if they prove things in a rational way.

Tanaka: I agree that art and science are not so far

in spirit. I have a scientic background, parallel to

my musical training. Technology arts such as com-

puter music give us the chance to show how close

these things have always been.

Karkowski: I think that there is always art before

the science.

Tanaka: The fact that science is rational and art

does not have to be is one distinguishing character-

istic.

van der Heide: Art is rational, too, but in a subjec-

tive way.

Tanaka: Art deals with the irrational in a way that

science does not.

Karkowski: Art created during the Surreal, Dada,

and Romantic movements was based in irratio-

nality.

Tanaka: Yes, these were art movements that delib-

erately eliminated rationalism. The difference be-

tween rational and irrational is interesting, but

more fascinating is to identify what kind of human

spirit can be inside a person who pursues scientic

research or who pursues musical creation. Having

worked in scientic research in music, I nd there

are some common creative components called

upon in the artist and in the researcher.

Bongers: There are many examples of great scien-

tists who have been good amateur musicians as

well.

Tanaka: And vice versa, there are many musicians

who are technically quite capable. Edwin, for ex-

ample, creates his own DSP programs, but for

purely musical reasons. As an artist, you must ques-

tion how many of these jobs you want to take on:

the instrument builder, the composer, the perfor-

mer, or all three.

van der Heide: It is a matter of attitude as well. I

am denitely not making my inventions to sell, be-

cause if I do that, I am not the artist anymore. For

example, developing inventions is still ne, but I

am not nurturing my artistic self when I start sell-

ing, doing business, and going to meetings.

Karkowski: One can always say he or she is a scien-

tist, or a soldier, or a doctor, but it is difcult to say

when one is an artist; it is generally something that

artists would not say about themselves. Of course,

there are exceptions like Beethoven or Wagner, but

even with them I think someone else called them

artists rst.

van der Heide: That is the problem right now be-

cause the denition of artist, the whole word art-

ist in discussion at this moment, is not a stable

thing anymore. If one says he or she is an artist or a

composer, people expect the person to be a painter

or write for an orchestra.

Karkowski: Actually, there have never been so

many artists in the world as there are now, because

the Western world is rich. We have money to spend

for art and education, and many countries even

have unions for painters and musicians.

Tanaka: When one goes to a record store, there is

so much music to choose from, it is almost de-

pressing. At the same time, technology is some-

thing that enables or democratizes the creative

process, so that the most idealistic people have the

notion that anyone can be an artist. But in the

22 Computer Music Journal

this tradition now. Before we started Sensorband,

the only person in the world I knew who made mu-

sic this way was Michel Waisvisz, and I saw him

perform several times. Generally, Michel inspired

me to some degree. . . . He is a great performer. . . .

[All agree.] For many years, he continued to per-

form with the same instrument, instead of continu-

ing to improve it technically.

Tanaka: We have precedents like Michel, and be-

fore that, Theremin and Max Mathews. In fact,

there is much research happening in our eld on

gestural control. But we should not forget about

purely musical inuences and artistic objectives.

This is what is newnot necessarily the technol-

ogy, or the idea of sensor control over computer-

generated music, but the aesthetic, structural ap-

proaches, and the performance practice we es-

tablish.

van der Heide: When one makes music, one should

develop ones own way of thinking, and not base it

on other peoples ideas. To a certain extent one can,

but one should always say, well, leave it, let us see

what happens if I do it myself. My instrument, the

MIDI-Conductor, is based on Michels instrument,

the Hands, but I use it differently than he does,

both musically and in performance practice.

Tanaka: While we may be part of a new tradition,

it is impossible to say that we are doing something

completely new. Artists are trying to come to grips

with where to move after postmodernism. Postmod-

ernism was one approach to dealing with the

wealth of historical knowledge we have. I am look-

ing for other ways to acknowledge the breadth of in-

uences we have, not in a collage-like way, but in

an integrated fashion.

Karkowski: I think that what we are doing is really

without tradition. Or if there is tradition, it would

be right at the rootsmusic as ritual, trance, and

pure energy. Sensorbands music is contemporary,

non-commercial, and we use new technology. We

want to communicate. Our concerts exploit energy,

we want the audience to feel like they have just got-

ten their batteries reloaded. We want them to feel

stronger and like better human beings.

Tanaka: Music is that art form that takes a certain

technique, requires a certain logical approach, but

at the same time, needs subconscious magic to be

hands of a creative person, technology can take on

a different dimension.

Karkowski: We are quite skeptical about technol-

ogy, but we are just using it. Still, the real issues we

are dealing with in the group are totally on a differ-

ent level.

Tanaka: We are not alone in being skeptical. This

is denitely the trend in technology in the artsto

question these things, and no longer just worship

technological advancements.

Inuences and Approaches

Bongers: Are there pioneers in the eld of live elec-

tronic music, new instruments, or other styles or

art forms who have inuenced your work?

van der Heide: I could mention a few names here

today, but tomorrow I would name three other

names.

Tanaka: Today, many artists have diverse inu-

ences. We are part of that generation. But at the

same time, we are attempting to distill some of

these inuences to present a pure message in our

music.

Karkowski: I really could not tell you my inu-

ences; I mean, there are many of them, but they all

change with time.

van der Heide: For a long time, artistic develop-

ment has been linear, where each movement has

been a reaction to a previous movement. The avant

garde has always been a reaction to what happened

before, but at this moment, we are reinventing the

language. A lot of things have been done before,

but not with this technology. There are a lot of

movements going on simultaneously now. You can-

not speak about a general linear development in

the arts anymore.

Tanaka: This is a product of the information age

we live in. These days, consumers can go to record

shops and choose any music of any period that they

want to hear. A hundred years ago, this was not the

case for either the listener or the composer. Now

we are more aware of different currents and inu-

ences than artists ever were before.

Karkowski: With Sensorband, we are creating some-

thing that really has no tradition. We are starting

23 Bongers

successful. In our art form, there is a balance be-

tween logic and intuition. Music often reacts late

to new artistic movements, but music is always

ahead of the other arts in issues of perception and

creative applications of technology. There are some

concrete examples of issues that we have been con-

fronting for a long time in computer music, such as

real time and interactivity, which have been ad-

dressed only recently in elds such as virtual real-

ity and computer graphics. Interactivity and real

time may be in vogue now, but time and communi-

cation are the essence of music. These are concepts

that are essential in our art form, independent of

technology. Musical performance has always had

multiple modes of interaction: between performer

and instrument, between conductor and orchestra,

and between musician and audience. The stage has

always been a real-time environment.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Anne Deane for her help in

editing this article.

References

Knapp, R. B., and H. S. Lusted. 1990. A Bioelectric Con-

troller for Computer Music Applications. Computer

Music Journal 14(1):4247.

Krefeld, V. 1990. The Hand in the Web: An Interview

with Michel Waisvisz. Computer Music Journal

14(2):2833.

Lusted, H. S., and R. B. Knapp. 1996. Controlling Com-

puters with Neural Signals. Scientic American

(October):5863.

24 Computer Music Journal

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Horacio Vaggione - CMJ - Interview by Osvaldo BudónDokumen13 halamanHoracio Vaggione - CMJ - Interview by Osvaldo BudónAlexis PerepelyciaBelum ada peringkat

- Guide To Unconventional Computing For MusicDokumen290 halamanGuide To Unconventional Computing For MusicSonnenschein100% (4)

- Erkki Kuriniemmi Principles2007 088Dokumen6 halamanErkki Kuriniemmi Principles2007 088Juan Duarte ReginoBelum ada peringkat

- Electronic Music Historical OverviewDokumen4 halamanElectronic Music Historical OverviewmehmetkurtulusBelum ada peringkat

- STEIM, A ReconstructionDokumen3 halamanSTEIM, A ReconstructionFrancescoDiMaggioBelum ada peringkat

- Pierre Boulez and Andrew Gerzso - Computers in MusicDokumen8 halamanPierre Boulez and Andrew Gerzso - Computers in MusicJorge A. Avilés100% (1)

- Koren On Dan TimisDokumen11 halamanKoren On Dan TimisMorel KorenBelum ada peringkat

- CD Program Notes: Ricardo Dal Farra, CuratorDokumen10 halamanCD Program Notes: Ricardo Dal Farra, CuratorpabloBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Electroacoustic Music PDFDokumen7 halamanIntroduction To Electroacoustic Music PDFRodrigo Fernandez100% (1)

- Curators: Collin Fallows, Heidi Grundmann Sound Drifting: I Silenzi Parlano Tra LoroDokumen6 halamanCurators: Collin Fallows, Heidi Grundmann Sound Drifting: I Silenzi Parlano Tra LoroMartínMaldonadoBelum ada peringkat

- Art of Articulation ReprintDokumen16 halamanArt of Articulation ReprintAndré Ferreira Pinto100% (1)

- Graphical Sound From Inception Up To TheDokumen6 halamanGraphical Sound From Inception Up To TheIlija AtanasovBelum ada peringkat

- Towards A Semiotic Model of Mixed Music AnalysisDokumen8 halamanTowards A Semiotic Model of Mixed Music AnalysismorgendorfferBelum ada peringkat

- Jean-Claude Risset - Fifty Years of Digital Sound For MusicDokumen6 halamanJean-Claude Risset - Fifty Years of Digital Sound For MusicVincent LostanlenBelum ada peringkat

- JohnChowning CurriculumDokumen9 halamanJohnChowning CurriculumGaia ParaciniBelum ada peringkat

- Klaus Obermaier MonographyDokumen12 halamanKlaus Obermaier MonographyGiorgos StylianouBelum ada peringkat

- Physical Interface in The Electronic ArtsDokumen45 halamanPhysical Interface in The Electronic ArtssbBelum ada peringkat

- Computer-Assisted Composition: A Short Historical ReviewDokumen3 halamanComputer-Assisted Composition: A Short Historical Reviewdice midyantiBelum ada peringkat

- SynthesizerDokumen4 halamanSynthesizersonsdoedenBelum ada peringkat

- From Organs To Computer MusicDokumen16 halamanFrom Organs To Computer Musicjoesh2Belum ada peringkat

- Alay 5Dokumen1 halamanAlay 5Jade Ann BrosoBelum ada peringkat

- E A TerminologyDokumen2 halamanE A Terminologyhockey66patBelum ada peringkat

- Electro-Acoustic Music Grove MusicDokumen17 halamanElectro-Acoustic Music Grove MusicAntonio García RuizBelum ada peringkat

- 98 3 JNMR Brain OperaDokumen30 halaman98 3 JNMR Brain OperaAlejandro OrdásBelum ada peringkat

- Continuamente Integrating Percussion AudiovisualDokumen4 halamanContinuamente Integrating Percussion AudiovisualipiresBelum ada peringkat

- Electronic Music Encyclopedia EntryDokumen5 halamanElectronic Music Encyclopedia EntryLucas eduardoBelum ada peringkat

- Varese e ElectronicDokumen62 halamanVarese e ElectronicieysimurraBelum ada peringkat

- ArtikulationDokumen15 halamanArtikulationAnonymous zzPvaL89fG100% (1)

- Towards Intelligent Orchestration System PDFDokumen11 halamanTowards Intelligent Orchestration System PDFlilithBelum ada peringkat

- "Classic" HyperinstrumentsDokumen10 halaman"Classic" HyperinstrumentsMatthias StrassmüllerBelum ada peringkat

- Les Ondes Martenot in Practice PDFDokumen28 halamanLes Ondes Martenot in Practice PDFAditya Nirvaan Ranga0% (1)

- EATerminology PDFDokumen2 halamanEATerminology PDFhockey66patBelum ada peringkat

- Regarding Electronic MusicDokumen12 halamanRegarding Electronic MusicMBelum ada peringkat

- About The AuthorDokumen2 halamanAbout The AuthorRodrigo SantosBelum ada peringkat

- About The AuthorDokumen2 halamanAbout The AuthorRodrigo SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Stockhausen Doc 1Dokumen8 halamanStockhausen Doc 1YungStingBelum ada peringkat

- Gottfried Michael Koenig Aesthetic Integration of Computer-Composed ScoresDokumen7 halamanGottfried Michael Koenig Aesthetic Integration of Computer-Composed ScoresChristophe RobertBelum ada peringkat

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimesDokumen3 halamanMusical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimeshelenaBelum ada peringkat

- Risset 2003 PDFDokumen17 halamanRisset 2003 PDFAbel CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Micro SoundDokumen423 halamanMicro SoundFernando Soberanes88% (8)

- A Short History of Digital Sound Synthesis by Composers in The U.S.ADokumen9 halamanA Short History of Digital Sound Synthesis by Composers in The U.S.AUnyilpapedaBelum ada peringkat

- Antony Reimagining - David WesselDokumen4 halamanAntony Reimagining - David Wesselmcain93Belum ada peringkat

- Path of Patches: Implementing An Evolutionary Soundscape Art InstallationDokumen11 halamanPath of Patches: Implementing An Evolutionary Soundscape Art InstallationJose FornariBelum ada peringkat

- Artificial Intelligence and MusicDokumen14 halamanArtificial Intelligence and MusicGary100% (1)

- A Study With Hyperinstruments in Free MuDokumen8 halamanA Study With Hyperinstruments in Free MuvladybystrovBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer PDFDokumen17 halamanContentServer PDFthor888888Belum ada peringkat

- Messa Di Voce DescriptionDokumen19 halamanMessa Di Voce DescriptionKenneth EvansBelum ada peringkat

- CSIM RTI SJorda03 InteractiveMusic LowRes PDFDokumen32 halamanCSIM RTI SJorda03 InteractiveMusic LowRes PDFStefano FranceschiniBelum ada peringkat

- MAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 6: Electronic Music (Stockhausen)Dokumen9 halamanMAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 6: Electronic Music (Stockhausen)Albert Ian CasugaBelum ada peringkat

- Brain-Computer Music Interface For Composition and PerformanceDokumen8 halamanBrain-Computer Music Interface For Composition and PerformanceAngelRibeiro10Belum ada peringkat

- Brain-Computer Music Interface For Generative Music PDFDokumen8 halamanBrain-Computer Music Interface For Generative Music PDFseerwan mohemmad mustafaBelum ada peringkat

- Music - Media - History: Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital MediaDari EverandMusic - Media - History: Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital MediaMatej SantiBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol 8, Issue 2/2022 - Algorithmic ArtDari EverandDigital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol 8, Issue 2/2022 - Algorithmic ArtMathias FuchsBelum ada peringkat

- Physics and Music: Essential Connections and Illuminating ExcursionsDari EverandPhysics and Music: Essential Connections and Illuminating ExcursionsBelum ada peringkat

- The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the WorldDari EverandThe Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the WorldPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (21)

- Kompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsDari EverandKompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsBelum ada peringkat

- Nime Identity From The Performer'S Perspective: Fabio Morreale Andrew P. Mcpherson Marcelo M. WanderleyDokumen6 halamanNime Identity From The Performer'S Perspective: Fabio Morreale Andrew P. Mcpherson Marcelo M. WanderleyTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Elemental & Cyrene Reefs: NIME 2009 337Dokumen1 halamanElemental & Cyrene Reefs: NIME 2009 337Trisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Contextualising Idiomatic Gestures in Musical Interactions With NimesDokumen6 halamanContextualising Idiomatic Gestures in Musical Interactions With NimesTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Kurenniemi Nime2007 088 PDFDokumen6 halamanKurenniemi Nime2007 088 PDFTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Vertical System (Voices) : Concrete Platform Bridge Board - WalkDokumen8 halamanVertical System (Voices) : Concrete Platform Bridge Board - WalkTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Principles For Designing Computer Music ControllersDokumen4 halamanPrinciples For Designing Computer Music ControllersTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Personalized Song Interaction Using A Multi-Touch InterfaceDokumen4 halamanPersonalized Song Interaction Using A Multi-Touch InterfaceTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- MIDI Keyboard Defined DJ Performance System: Christopher Dewey Jonathan P. Wakefield Matthew TindallDokumen2 halamanMIDI Keyboard Defined DJ Performance System: Christopher Dewey Jonathan P. Wakefield Matthew TindallTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Designing Dmis For Popular Music in The Brazilian Northeast: Lessons LearnedDokumen4 halamanDesigning Dmis For Popular Music in The Brazilian Northeast: Lessons LearnedTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Song Kernel: Explorations in Intuitive Use of Harmony: Juan BenderDokumen2 halamanSong Kernel: Explorations in Intuitive Use of Harmony: Juan BenderTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- NIME03 Gaye PDFDokumen7 halamanNIME03 Gaye PDFTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Casio CTK50 Service ManualDokumen16 halamanCasio CTK50 Service ManualTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- TL074Dokumen12 halamanTL074Trisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Afasia: The Ultimate Homeric One-Man-Multimedia-Band: Sergi JordàDokumen6 halamanAfasia: The Ultimate Homeric One-Man-Multimedia-Band: Sergi JordàTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- Some Comments About Electroacoustic Music and Life in Latin America - Ricardo Dal FarraDokumen3 halamanSome Comments About Electroacoustic Music and Life in Latin America - Ricardo Dal FarraTrisha JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- William Shakespeare - WikipediaDokumen1 halamanWilliam Shakespeare - WikipediaGBelum ada peringkat

- Stair Building GuideDokumen2 halamanStair Building Guideace tyBelum ada peringkat

- ADVERT 3217 MODULE 1 - The Creative ThinkingDokumen25 halamanADVERT 3217 MODULE 1 - The Creative ThinkingsaphirejunelBelum ada peringkat

- CV Jade Bantug 2019Dokumen6 halamanCV Jade Bantug 2019James Adrian MoralBelum ada peringkat

- Glass Con Papers 2014Dokumen796 halamanGlass Con Papers 2014Mervyn100% (1)

- Adidas ZDHC List Feb2017 FinalDokumen28 halamanAdidas ZDHC List Feb2017 FinalRatu FirnaBelum ada peringkat

- J.D.Beazley-Groups of Early Attic Black-Figure-1944 PDFDokumen28 halamanJ.D.Beazley-Groups of Early Attic Black-Figure-1944 PDFMurat SaygılıBelum ada peringkat

- Ledged, Braced, Battened & Framed DoorsDokumen8 halamanLedged, Braced, Battened & Framed DoorsUmesh Chakravarti100% (1)

- Halsey 'New Americana' Transcript PDFDokumen2 halamanHalsey 'New Americana' Transcript PDFalexander_stapletonBelum ada peringkat

- RGB Color-Phrase Fullsearch-UsDokumen378 halamanRGB Color-Phrase Fullsearch-UsHendra GoBelum ada peringkat

- Taekwondo Manual 1959Dokumen167 halamanTaekwondo Manual 1959Almir Souza Jr.67% (6)

- Ahonge - A Project ReportDokumen19 halamanAhonge - A Project ReportAmusers0% (1)

- Beer Tasting PaddlesDokumen12 halamanBeer Tasting PaddlesAdriano KytBelum ada peringkat

- MELANCHOLIA or The Romantic Anti Sublime SEQUENCE 1.1 2012 Steven ShaviroDokumen58 halamanMELANCHOLIA or The Romantic Anti Sublime SEQUENCE 1.1 2012 Steven ShaviroRuy CastroBelum ada peringkat

- An Optimum Modern Spinning Methods Achieving Physiological Comfort in Circular Weft Knitting Fabrics.Dokumen12 halamanAn Optimum Modern Spinning Methods Achieving Physiological Comfort in Circular Weft Knitting Fabrics.Hadir DeyabBelum ada peringkat

- A Raisin in The Sun EssayDokumen6 halamanA Raisin in The Sun EssayerinBelum ada peringkat

- Perawan Kelompok 2 Selaput Ekstra EmbrionikDokumen37 halamanPerawan Kelompok 2 Selaput Ekstra EmbrionikmusdalifaBelum ada peringkat

- An Interview With Grandmaster Yip Man From 1972: Wooden DummyDokumen13 halamanAn Interview With Grandmaster Yip Man From 1972: Wooden DummynambaccucBelum ada peringkat

- Periodical TEST GRADE 10Dokumen3 halamanPeriodical TEST GRADE 10SHEILA MAE PERTIMOS100% (2)

- CPAR (Music and Dance)Dokumen69 halamanCPAR (Music and Dance)Eisenhower SabaBelum ada peringkat

- NOVEMBER 9 2007 No 5458Dokumen36 halamanNOVEMBER 9 2007 No 5458salisoftBelum ada peringkat

- Visit Greece Myths KS2Dokumen19 halamanVisit Greece Myths KS2Jobell AguvidaBelum ada peringkat

- Hip Pouch by Daisy JanieDokumen4 halamanHip Pouch by Daisy JanieRéka DeákBelum ada peringkat

- Pica Pau PenguintoDokumen3 halamanPica Pau Penguintominidagger75% (4)

- Band KarateDokumen3 halamanBand KaratejpBelum ada peringkat

- Speakout Intermediate Plus BBC DVD ExtraDokumen5 halamanSpeakout Intermediate Plus BBC DVD ExtraMatías Reviriego RomeroBelum ada peringkat

- Instrumentally YoursDokumen9 halamanInstrumentally YoursShiv GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Observation EssayDokumen5 halamanObservation Essayapi-319757396Belum ada peringkat

- Louisiana State University School of Theatre Beginner Ballet Course Number: THTR 1131, Spring 2016Dokumen6 halamanLouisiana State University School of Theatre Beginner Ballet Course Number: THTR 1131, Spring 2016austin venturaBelum ada peringkat

- Daily Progress Report: Aiims BilanpurDokumen2 halamanDaily Progress Report: Aiims BilanpurAnkit JainBelum ada peringkat