Philosophy of Language Quine Vs Grice and Strawson

Diunggah oleh

jeffreyalix0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

176 tayangan8 halamanA school paper on Quine's Two Dogmas and Grice and Strawson's joint-reply to his criticisms.

Judul Asli

Philosophy of Language Quine vs Grice and Strawson

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniA school paper on Quine's Two Dogmas and Grice and Strawson's joint-reply to his criticisms.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

176 tayangan8 halamanPhilosophy of Language Quine Vs Grice and Strawson

Diunggah oleh

jeffreyalixA school paper on Quine's Two Dogmas and Grice and Strawson's joint-reply to his criticisms.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 8

Philosophy of Language

Allen Jeffrey Gurfel

What are the two dogmas of empiricism, according to Quine? Why does he allege

that the two are, in fact, at root identical? Explain in your own words. How do Grice

and Strawson suggest the notion of analyticity might be retained in a modified form?

Is this maneuver successful, in your view? Why or why not?

In his paper Two Dogmas of Empiricism W.V.O. Quine argues that empiricists have

taken two beliefs for granted, each of these a mere metaphysical article of faith.

First, Quine calls out the lack of a principled distinction between analytic and

synthetic truths. Such a distinction is not on firm ground and the faith that there is

such a distinction to be drawn at all is an unempirical dogma of empiricists.

Quine outlines the trouble for several attempts at elaborating analyticity. For

example: if we attempt to ground analyticity in synonymy then we owe an

elaboration of synonymy. There is one case in which this might work: when we

conjure up a synonym with an express definition and agree to use it in the explicitly

specified manner by convention. This is not, however, typical of synonyms and so

doesnt meet the bill in the majority of cases. We cant simply refer to the dictionary

definition since the lexicographer is not inventing synonymous words in the way

stated above but rather recording an empirical observation about words and their

common usage. If we attempt to give an account of synonymy (in the way required

to ground analyticity) in terms of interchangeability salva veritate we still run into

the problem outlined presently. Take the statement Necessarily all and only

bachelors are bachelors. If this statement is true and bachelors is interchangeable

salva veritate with unmarried men, then the following statement is also true:

Necessarily all and only bachelors are unmarried men. It follows that the statement

All and only bachelors are unmarried men is an analytic statement. Here, Quines

gripe is with the word necessarily. If we are considering a purely extensional

language, then synonymy boils down to something weaker than desired. All and

only bachelors are unmarried men may be true but so only accidentally. Its true in

virtue of extensional agreement, but then there is also extensional agreement

between creature with a heart and creature with a kidney. Yes, they pick out an

identical set of creatures, but they mean obviously different things and suggest no

logical necessity. The intentional term necessarily doesnt do the trick for us

because it is intelligible only in the context of a language in which the notion of

analyticity is already understood in advance.

Neither can we appeal to brute postulates in a simplified, artificial language that

eliminates the complexities and convolutions of natural language. The rules of the

language may point out which of its statements are analytic. However, this wont tell

us what analyticity itself consists in. The set of analytic statements in this language

will be a subset of true statements in the language, such that each member is true in

virtue of a semantic rule. But what exactly is this semantic rule? There might be

numerous rules that pick out subsets of true statements in the language in terms of

various arbitrary rules. This brings us no closer to an account specifically of

analyticity.

Second, Quine attacks a darling of empiricism, the verification theory of meaning

and reductionism.

The verification theory is that the meaning of a statement is the method of

empirically confirming or infirming it. It aims to tie statements to particular states

of the world and our sensory-experiential access to those states. Only those

statements which can be confirmed or infirmed empirically by experience, and

thereby judged either true or false, are meaningful. In this context, an analytical

statement is one which logically always confirmed, it is confirmed come what may.

Quine takes it as settled that analyticity is not on firm ground. He further denies that

a statement can be confirmed or disconfirmed in isolation from all other statements.

For Quine, these are all part of a web. Some statements we hold to be true or false

are more recalcitrant than others. We may revise them in light of experience, but

there is an attendant revision of other parts of our web of beliefs. Furthermore, only

a portion of our beliefs, our affirmations of various statements as true or false, are

on the periphery, so to speak, directly in touch with experience. The main point for

Quine is that there are no analytic statements if by that we mean statements that are

confirmed come what may. All statements can, under that definition, be analytic

statements provided were willing to make the necessary revisions elsewhere in our

webnothing is immune to revision, not even our statements of logical rules. This

insistence on considering the whole web of beliefs undermines verificationisms

hope of grounding analyticity in synonymy by defining synonymous statements

considered on their own, in isolation as those with identical methods of empirical

confirmation and information.

H.P. Grice and P.F. Strawson argue, in their paper In Defense of a Dogma, that Quine,

for all that he has shown and argued, is not justified in his wholesale dismissal of the

analytic/synthetic distinction as illusory.

First, Grice and Strawson question Quines conditions for an adequate elaboration of

the distinction, suggesting that they may be so strict as to rule out any and all

elaboration.

Second, they offer a possible explanation of the distinction, without using any of the

related terms Quine rules out as equally in need of clarification, such that would

enable a user of the terms analytic and synthetic to use them in the correct way, in

agreement with how they are typically used.

Third, they focus on the fact that these terms have been applied, consistently and

with great uniformity, by a huge portion of philosophers in the Western tradition.

This all adds up to a very strong prima facie plausibility for the analytic/synthetic

distinction. We can emphasize this initial plausibility by noting that Quine would

have to hold that the phrases means the same as and does not mean the same as

amount to meaninglessness. Further, it would follow that sentences could have no

meaning at all, since the question What does this sentence mean? would become

unanswerable.

In sum, that the distinction is not (yet) perfectly rigorous does not suggest that it

does not exist, especially in the face of such great prima facie plausibility.

Next Grice and Strawson turn to Quines counter-position about webs of belief.

Quines theory does not foreclose on the coherence of the analytic/synthetic

distinction. Rather, it demands an alteration or amendment that takes into

consideration and accounts for the possible revisions in the web. Essentially, they

suggest we can add a ceteris parabus clause: All we have to say now is that two

statements are synonymous if and only if any experiences which, on certain

assumptions about the truth-values of other statements, confirm or disconfirm one of

the pair, also, on the same assumptions, confirm or disconfirm the other to the same

degree. Here we can accept Quines theory and preserve a synonymy account of

analyticity. Similarly, we can accept Quines revisability in principle of everything

we say and maintain our account of analyticity so long as we can make sense of the

idea of conceptual revision. We can admit that there is no necessity to maintain one

conceptual scheme over another conceptual scheme, but still hold that analyticity

makes perfect sense within any given conceptual scheme.

I agree with Grice and Strawsons criticism of Quines attacks on the attempts to

rigorously delineate analytic and synthetic truths. It is an immensely plausible

distinction. Grice and Strawson clearly illustrate the difference between logical and

natural impossibility with their example. Quine has not made any argument to the

effect that it is either a) in principal impossible to clearly draw the distinction or b)

necessary to do so. It seems an empirical fact that countless competent users have

been able to make the distinction with great consistency. I think this suggests that

there is, in fact, a principled distinction there and so the faith in this distinction is

not mere unempirical dogma.

I also agree that analyticity can be preserved in Quines theory in precisely the way

Grice and Strawson broadly outline. That analyticity should apply within a given

conceptual scheme is clear. I dont think its an objection to it that Bob, whos lost his

damn mind, can begin to deny the analyticity of All bachelors are married men

granted that all the beliefs he previously held have been thrown into complete

disarray. We get nowhere fast if we just claim If you go crazy enough, you can

believe anything you want no matter what. Just as Quine accepts certain truths

about logic and reason, certain definitions of terms, when he writes a paper, and

uses these to construct arguments which follow granted certain other beliefs, so too

are some statements analytic granted the avowed truth of certain other statements

and beliefs.

It seems that for Quine to deny this he would have to say that those statements are

precisely not analytic and so because some fact about his web theory makes them

very much not what were looking for in an analytic statement. This would require

him to say what we are looking for in an analytic statement. He is presumably

unable to do so (because then, problem solved) or able to do so only in terms of

verificationism. But weve already seen how that account can be amended to work

with Quines theory. Then any statement might be an analytic given certain other

beliefs. The same statement might be analytic for one person with belief set X and

not analytic for another person with belief set Y. Can we make sense of that? Well,

like with anything, given certain beliefs we can. It seems, then, that we can preserve

the distinction but not without undermining the concept, moving it into a very

subjective realm of private meanings and beliefs. But then, wasnt it that to begin

with, only with the added assumption that we were all, though subjectively, more or

less on the same page, sharing many of the relevant beliefs? I think we often are and

do and so the distinction is useful, fairly clear, principled in some way or other, and

pragmatic. If we see this as a downgrade for analyticity, so be it. We should be

careful about the philosophical work we want analytic statements to doasking if,

on Grice and Strawsons Quinean view of analyticity, they are capable of bearing the

load. (We might also ask what difference the degree of truth and falsity of the

background beliefs might make. For Quine, given his remarks about the

mythological gods and physical objects, this question might be beside the point.) If it

turns out that they cant do the logical work weve had them doing, if unmasked they

were left with no pragmatic purpose, then maybe I would agree with Quine that the

distinction is not only useless but illusory, like a ghost lifting weights.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Heart of Grief: Death and The Search For Lasting LoveDokumen310 halamanThe Heart of Grief: Death and The Search For Lasting LovejeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Terapia de Fala e Linguagem FatosDokumen28 halamanTerapia de Fala e Linguagem FatosTamiris Alves100% (1)

- Nicomachean Ethics Summary by ChaptersDokumen5 halamanNicomachean Ethics Summary by ChaptersScribdTranslationsBelum ada peringkat

- Kant's Moral LawDokumen10 halamanKant's Moral LawRokibul HasanBelum ada peringkat

- Universalist History of The 1987 Philippine ConstitutionDokumen59 halamanUniversalist History of The 1987 Philippine ConstitutionAgent BlueBelum ada peringkat

- Carnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageDokumen14 halamanCarnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageEdvardvsBelum ada peringkat

- Linkers and Connectors: Purpose and ResultDokumen3 halamanLinkers and Connectors: Purpose and ResultMaria Suanes100% (2)

- Russell On StrawsonDokumen3 halamanRussell On Strawsonkataru001100% (1)

- Two Dogmas of Empiricism: Quine's Critique of Analyticity and ReductionismDokumen3 halamanTwo Dogmas of Empiricism: Quine's Critique of Analyticity and Reductionismtoto BeyutBelum ada peringkat

- Plato and AristotleDokumen2 halamanPlato and AristotleTanya TandonBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Propaganda in Soviet Russia: Case Study OneDokumen8 halamanVisual Propaganda in Soviet Russia: Case Study OneManea IrinaBelum ada peringkat

- Nozick's Wilt Chamberlain Argument, Cohen's Response, and NotesDokumen7 halamanNozick's Wilt Chamberlain Argument, Cohen's Response, and Notesjeffreyalix0% (1)

- KantDokumen24 halamanKantPaul John HarrisonBelum ada peringkat

- Greek Grammar HandoutDokumen72 halamanGreek Grammar HandoutGuy Colvin100% (1)

- Habana vs. RoblesDokumen2 halamanHabana vs. RoblesLloyd David P. VicedoBelum ada peringkat

- Filipino Philosophy Past and Present 201 PDFDokumen14 halamanFilipino Philosophy Past and Present 201 PDFJhon Mark Luces OtillaBelum ada peringkat

- Early Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-PhilosophicusDokumen7 halamanEarly Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusredd salariaBelum ada peringkat

- Utilitarianism and Human RightsDokumen8 halamanUtilitarianism and Human RightsMikhael O. SantosBelum ada peringkat

- John Stuart Mill Individuality Dignity and RespectDokumen20 halamanJohn Stuart Mill Individuality Dignity and Respectزهرة الزنبق زهرة الزنبقBelum ada peringkat

- Latin Direct Obj 2Dokumen2 halamanLatin Direct Obj 2Magister Cummings75% (4)

- Socrates' Vow to Disobey the JuryDokumen10 halamanSocrates' Vow to Disobey the Juryvince34Belum ada peringkat

- Ludwig Wittgenstein LANGUAGE GAMESDokumen10 halamanLudwig Wittgenstein LANGUAGE GAMESFiorenzo TassottiBelum ada peringkat

- 03 Edamura TheDeisticGod 124 PDFDokumen14 halaman03 Edamura TheDeisticGod 124 PDFPurandarBelum ada peringkat

- Brief History of Britain 1Dokumen33 halamanBrief History of Britain 1Mohamed Anass Zemmouri100% (2)

- Sunstein - On Analogical ReasoningDokumen52 halamanSunstein - On Analogical ReasoningTris LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Paradise Lost Eve's DisobedienceDokumen17 halamanParadise Lost Eve's Disobediencejeffreyalix100% (1)

- Mood Analysis SFLDokumen13 halamanMood Analysis SFLangopth100% (2)

- (István - Pieter - Bejczy) Virtue Ethics in The Middle AgesDokumen385 halaman(István - Pieter - Bejczy) Virtue Ethics in The Middle Agesjeffreyalix100% (1)

- Language Game (Philosophy)Dokumen3 halamanLanguage Game (Philosophy)genangkuBelum ada peringkat

- The "Modes" of Spinoza and The "Monads" of LeibnizDokumen35 halamanThe "Modes" of Spinoza and The "Monads" of LeibnizjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- What Is A Scientific Explanation?Dokumen6 halamanWhat Is A Scientific Explanation?Nick Fletcher100% (3)

- Non-Cognitivism in EthicsDokumen14 halamanNon-Cognitivism in EthicsPantatNyanehBurikBelum ada peringkat

- 12.3 Appraising Analogical ArgumentsDokumen2 halaman12.3 Appraising Analogical Argumentszeepakingshit100% (1)

- A. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsDokumen1 halamanA. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsSyed Zafar ImamBelum ada peringkat

- Document 1Dokumen8 halamanDocument 1merchBelum ada peringkat

- Wittgenstein Picture TheoryDokumen4 halamanWittgenstein Picture TheoryAlladi Bhadra Rao DevangaBelum ada peringkat

- L Fuller, Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor HartDokumen44 halamanL Fuller, Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor HartBrandon LimBelum ada peringkat

- Hart-Finnis Debate (Critical Review)Dokumen9 halamanHart-Finnis Debate (Critical Review)Muktesh SwamyBelum ada peringkat

- Anthro KDokumen66 halamanAnthro KHolden ChoiBelum ada peringkat

- Notes on Logic and Critical ThinkingDokumen2 halamanNotes on Logic and Critical ThinkingAkif JamalBelum ada peringkat

- W. Neil Adger, Jouni Paavola, Saleemul Huq, M. J. Mace - Fairness in Adaptation To Climate Change (2006, The MIT Press)Dokumen337 halamanW. Neil Adger, Jouni Paavola, Saleemul Huq, M. J. Mace - Fairness in Adaptation To Climate Change (2006, The MIT Press)Liam DevineBelum ada peringkat

- What Are AI Content Detectors and How To Outsmart Them?Dokumen13 halamanWhat Are AI Content Detectors and How To Outsmart Them?Narrato SocialBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Concept of Discourse AnalysisDokumen3 halamanBasic Concept of Discourse AnalysisShabirin AlmaharBelum ada peringkat

- Historical School of ThoughtDokumen54 halamanHistorical School of Thoughtmadhan ravi100% (1)

- Truth and Knowledge HandoutDokumen6 halamanTruth and Knowledge HandoutMatthew ChenBelum ada peringkat

- Su2so3su3 PDFDokumen10 halamanSu2so3su3 PDFRusli AditiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Traditional Metaphysics Problems Resolved by PhenomenologyDokumen2 halamanTraditional Metaphysics Problems Resolved by PhenomenologyIfeoma UnachukwuBelum ada peringkat

- Branches of PhilosophyDokumen4 halamanBranches of PhilosophyJui Aquino ProvidoBelum ada peringkat

- SyllogismDokumen36 halamanSyllogismsakuraleeshaoranBelum ada peringkat

- Callicles' Quotation of Pindar in The Gorgias (1994)Dokumen24 halamanCallicles' Quotation of Pindar in The Gorgias (1994)mysticmdBelum ada peringkat

- Chavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilDokumen74 halamanChavez vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilRico UrbanoBelum ada peringkat

- Possible World SemanticsDokumen3 halamanPossible World SemanticsTiffany DavisBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 DDokumen3 halamanChapter 1 Dzyl manuelBelum ada peringkat

- On The Semantics of Ought To DoDokumen20 halamanOn The Semantics of Ought To DoGustavo VilarBelum ada peringkat

- Raz's Normative Theory of Authority. An Internal CritiqueDokumen21 halamanRaz's Normative Theory of Authority. An Internal CritiquecoxfnBelum ada peringkat

- Aristotle, RhetoricDokumen4 halamanAristotle, RhetoricMatheus de BritoBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Medical Association: Position Paper On TheDokumen8 halamanPhilippine Medical Association: Position Paper On TheCBCP for LifeBelum ada peringkat

- Civil Society in ChinaDokumen17 halamanCivil Society in ChinaMichael JeiveBelum ada peringkat

- Historical Perspective of Human RightsDokumen23 halamanHistorical Perspective of Human RightsMrudula JoshiBelum ada peringkat

- Arguments in Ordinary LanguageDokumen5 halamanArguments in Ordinary LanguageStephanie Reyes GoBelum ada peringkat

- The Bet 2 EDITEDDokumen2 halamanThe Bet 2 EDITEDNandan GarapatiBelum ada peringkat

- John Locke On Property RightsDokumen5 halamanJohn Locke On Property RightsErik F. Meinhardt95% (19)

- Lon L. Fuller, Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor HartDokumen2 halamanLon L. Fuller, Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor Hartjjap123Belum ada peringkat

- Medieval Philosophy Key ConceptsDokumen7 halamanMedieval Philosophy Key ConceptsKeneleen Camisora Granito LamsinBelum ada peringkat

- The Philosophy of Motion Pictures: A Rejoinder To Noël Carroll'sDokumen10 halamanThe Philosophy of Motion Pictures: A Rejoinder To Noël Carroll'sjawharaBelum ada peringkat

- Dworkin's Right Thesis ExplainedDokumen6 halamanDworkin's Right Thesis ExplainedDanica BlancheBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of Human RightsDokumen3 halamanTheories of Human RightsNazra NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Forall: York Edition Solutions BookletDokumen91 halamanForall: York Edition Solutions BookletExist/Belum ada peringkat

- A Quinean Definition of SynonymyDokumen40 halamanA Quinean Definition of SynonymyWiwienBelum ada peringkat

- Revisability and Conceptual Change: David J. ChalmersDokumen26 halamanRevisability and Conceptual Change: David J. Chalmerswinwin11Belum ada peringkat

- Alfred Ayer The Criterion of TruthDokumen5 halamanAlfred Ayer The Criterion of TruthMoncif DaoudiBelum ada peringkat

- Defending A Dogma: Between Grice, Strawson and Quine: Elvis ImafidonDokumen10 halamanDefending A Dogma: Between Grice, Strawson and Quine: Elvis ImafidonYang Wen-LiBelum ada peringkat

- Milton MidtermDokumen9 halamanMilton MidtermjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Out To ForgetDokumen4 halamanOut To ForgetjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Spinoza's Ethics IV VDokumen27 halamanSpinoza's Ethics IV VjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Art Its History and MeaningDokumen16 halamanArt Its History and MeaningjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Gender and SocietyDokumen10 halamanGender and SocietyjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On Greek GrammarDokumen10 halamanNotes On Greek GrammarjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Spinoza's Ethics 3Dokumen32 halamanSpinoza's Ethics 3jeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On Kant's Introduction To The CPRDokumen2 halamanNotes On Kant's Introduction To The CPRjeffreyalix100% (1)

- Kekes Is WrongDokumen18 halamanKekes Is WrongjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Happiness and TimeDokumen11 halamanHappiness and TimejeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Knowing The Essence of The State in Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-PoliticusDokumen27 halamanKnowing The Essence of The State in Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-PoliticusjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Get Home SafelyDokumen9 halamanGet Home SafelyjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Spinoza's Ethics and Aristotle's MetaphysicsDokumen19 halamanSpinoza's Ethics and Aristotle's MetaphysicsjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Oedipus and Phaedra as Tragic HeroesDokumen6 halamanOedipus and Phaedra as Tragic HeroesjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Antidiscrimination LawDokumen29 halamanAntidiscrimination LawjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Hobbes vs Rousseau Views on Human Nature and Political OrganizationDokumen3 halamanHobbes vs Rousseau Views on Human Nature and Political OrganizationjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Chinese Room ReconsideredDokumen36 halamanChinese Room ReconsideredjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Rawls' Original Position and Difference PrincipleDokumen6 halamanRawls' Original Position and Difference PrinciplejeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- False Dichotomy: Objective vs. Subjective Interpretation of Spinoza's AttributesDokumen29 halamanFalse Dichotomy: Objective vs. Subjective Interpretation of Spinoza's AttributesjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Gurfel MedeaDokumen4 halamanGurfel MedeajeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Rawls' Original Position and Difference PrincipleDokumen6 halamanRawls' Original Position and Difference PrinciplejeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- Metz Imaginary ScreenDokumen63 halamanMetz Imaginary ScreenjeffreyalixBelum ada peringkat

- 411-1081-1-PB Althussar Gatari PDFDokumen16 halaman411-1081-1-PB Althussar Gatari PDFgaweshajeewaniBelum ada peringkat

- Apsa Style Manual 2006Dokumen50 halamanApsa Style Manual 2006enrique_gariaBelum ada peringkat

- RevisionDokumen2 halamanRevisiongia kiên phạm nguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- The British Numismatic Society: A History / Hugh PaganDokumen73 halamanThe British Numismatic Society: A History / Hugh PaganDigital Library Numis (DLN)Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluating Creative NonfictionDokumen3 halamanEvaluating Creative NonfictionTroy EslaoBelum ada peringkat

- Full & FinalDokumen892 halamanFull & FinalShahriar HossainBelum ada peringkat

- CBT Books Catalogue English PDFDokumen58 halamanCBT Books Catalogue English PDFIndus Public School Pillu KheraBelum ada peringkat

- JS 1 - Chapter 1Dokumen22 halamanJS 1 - Chapter 1Desi Nur AbdiBelum ada peringkat

- An Anthology of Belgian Symbolist Poets PDFDokumen268 halamanAn Anthology of Belgian Symbolist Poets PDFvallaths100% (1)

- Sastra InggrisDokumen3 halamanSastra InggrisTantri NaratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Certificate of Secondary Examination Syllabus 2016-17 (X STD)Dokumen273 halamanIndian Certificate of Secondary Examination Syllabus 2016-17 (X STD)Arockia RajaBelum ada peringkat

- HSK Beginner Speaking Test GuideDokumen4 halamanHSK Beginner Speaking Test GuideRufat SharafliBelum ada peringkat

- Block Syllabus Class 5Dokumen1 halamanBlock Syllabus Class 5Laiba ManzoorBelum ada peringkat

- 01Dokumen11 halaman01Gaming FF PCBelum ada peringkat

- AbacusDokumen2 halamanAbacusgtmchandrasBelum ada peringkat

- Data-Driven Selenium Tests with TestNGDokumen9 halamanData-Driven Selenium Tests with TestNGThiru RaoBelum ada peringkat

- Theory of Computation - Context Free LanguagesDokumen25 halamanTheory of Computation - Context Free LanguagesBhabatosh SinhaBelum ada peringkat

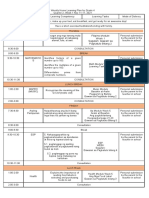

- Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade 4Dokumen2 halamanWeekly Home Learning Plan Grade 4MA. ISABELLA BALLESTEROSBelum ada peringkat

- CRM Report Assesses Luxury Retail StrategyDokumen5 halamanCRM Report Assesses Luxury Retail Strategyashraf950% (2)

- Gerund or Infinitive - 15232Dokumen1 halamanGerund or Infinitive - 15232CarlosRafaelMejíaMangasBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson plan on technological devicesDokumen20 halamanLesson plan on technological devicesKhoa Lê Trường AnhBelum ada peringkat

- Reading FluencyDokumen2 halamanReading FluencyTiffany Galloway100% (1)

- XLR K2MDokumen4 halamanXLR K2Manthonypardo100% (1)

- Maximo7 5 v4Dokumen73 halamanMaximo7 5 v4Chinna BhupalBelum ada peringkat

- Using XbenchDokumen73 halamanUsing XbenchgonniffBelum ada peringkat