Joy Vigil-Effective Interventions and Academic Support Action Research

Diunggah oleh

JoyVigilHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Joy Vigil-Effective Interventions and Academic Support Action Research

Diunggah oleh

JoyVigilHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 1

Effective Interventions and Academic Support for Junior High Students Action Research

Joy E. Vigil

University of Colorado, Denver

Fall 2013

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 2

Table of Contents

Introduction and Problem Statement

Purpose and Intended Audience

Research Questions

Context of Study

Literature Review

Literature Review Questions

Literature Search Procedures

Literature Review Findings

Quality of Literature

Gap in Literature

Summary of Literature Review

Methods

Site Selection and Sampling

Ethical Procedures

Data Collection Methods

Data Analysis Methods

Schedule

Checks for Rigor

Findings

Academic Support Trends

R.O.A.R. Trends

Comparison of Research to the Literature Review

Limitations

Implications of Practice

Impact (Negative and Positive)

Summary of Research

References

Appendices

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 3

Introduction and Problem Statement

Currently I am a Junior High and High School teacher in a suburban charter school in Colorado.

I have taught for five years and am a lead team member of the Junior High staff. Additionally,

after a lot of staff turnover in the previous school year, it has been up to the lead team members

and administration to retain the cultural traditions of the school as well as promote the various

forms of programs available to the students.

As students transition from the different educational expectations in elementary to Junior High,

many students struggle with keeping up on all of their work. Students now have eight different

teachers, transitioning from class to class, as well as being in 90-minute block class periods.

Currently we have two forms of interventions to support the academic needs of 7

th

and 8

th

grade

students. One intervention is called R.O.A.R., which stands for Reinforcement of Academic

Responsibility, and the other is called Academic Support. They both essentially provide the same

support. R.O.A.R. occurs after school with limited participation and is optional. Academic

Support occurs during school and is required for students with Ds and Fs with high

participation. So I conducted research to find out which intervention fits the needs of the Junior

High students best?

Purpose and Intended Audience

Allocating and distributing time appropriately within the teaching profession is challenging and

essential to being a successful teacher. Therefore to fully establish if a particular program is

effective, this researcher wanted to observe student behavior and participation in both R.O.A.R.

and Academic Support. In doing so, it would allow the lead team and administration to

determine where teachers time would best be used for the betterment of the students academic

success.

This information was shared with our Parent-lead Board of Directors which would thereby make

the research public for parents and students who were interested. The Board meetings are public

and their notes are posted on our school website.

Additionally, the information was shared with the students and instructor of the INTE 6720

Action Research class at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Research Questions

By observing students participation in both R.O.A.R. and Academic Support, the lead team and

administration of the Junior High program could better understand how the intervention

programs were affecting the achievement of students. Using data to observe trends in student

achievement is an important step to identifying possible causes of failures, successes, and areas

of effectiveness.

To determine which program best supports students needs along with the most efficient use of

teachers time, the questions this researcher delved into include:

To what extent are the current academic interventions offered at The Academy

effective for the student population?

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 4

Is providing Academic Support an effective intervention for 7th and 8th

grade students? By observing grade point averages of students attending

Academic Support, I checked for improvement of students grades. I checked if

grades improved for students who are mandated to attend. How did students feel

about being assigned Academic Support? Did it encourage them to not have a D

or F? Did missing out on lunch with their friends and advisory (called Pride Time)

recess also ensure they had passing grades?

Is providing optional R.O.A.R. an effective intervention for seventh and

eighth grade students? Similarly to Academic Support, the effectiveness of

R.O.A.R. was tracked by observing grade point averages and surveying teachers,

parents, and students.

Do parents find one form of intervention better than the other? It is important

to understand the potential buy-in of parents because they can potentially

influence the students participation and opinion of the interventions. Both take a

considerable amount of effort and manpower to run each week, so it is vital to

determine if they were both appropriate forms of interventions. Also, if there was

little buy-in from parents (who provided the students with a ride from R.O.A.R.),

it may not be highly attended.

In the end, I changed the research questions and excluded the eighth graders. This was due to the

among of data available from just one grade. There were also some complications in obtaining

Grade Point Averages which will be discussed later.

Context of Study

The research was conducted in a charter school that has two facilities housing Pre-K through 12

th

grade. This school is a part of a local school district and will have been open for 20 years at the

end of the 2013-2014 school year. The charter school has a high involvement of parents with a

parent board coordinating with the administrators and executive director to make decisions for

the school. Within the district, the student population sits at 56.88% White, 33.16% Hispanic,

5.15% Asian, 2.32% African-American, 0.68% Native American, 0.15% Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 1.65% two or more ethnicities. Within the charter school, the

student population is 71% White, 25% Hispanic, 3% Asian, 1% African-American, 0% Native

American, 0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 1% two or more ethnicities. The school is a

commuter school with no bus service available to families. There is a 16% of students who are

eligible for the free or reduced-price lunch program.

During the 2012-2013 school year, Academic Support was implemented as a form of in-school

intervention for all students in 7th and 8th grade who have a D or an F in any given class. Each

week, teachers would assign a student Academic Support on Tuesday. Then on Wednesday, the

students Pride Time (homeroom) teacher would give him/her a pass to Academic Support for

Thursday. The pass listed the class and the assignment(s) that the student must work on. The

student then had the opportunity to get the missing assignments turned in up to the point of

Academic Support on Thursday. If he/she is unable to turn in all of the assignments, he/she

would bring lunch to the classroom to work on the missing assignments. On Thursdays, we also

had recess during Pride Time. The students assigned to Academic Support missed out on both

lunch in the cafeteria and recess.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 5

The program Reinforcement of Academic Responsibility, also known as R.O.A.R., was

implemented during the 2007-2008 school year. The intention of the Tuesday after-school study

hall was to have all of the Junior High teachers in a localized spot to help students with their

schoolwork. Students could come on a voluntary basis and were encouraged to attend by all

teachers. If a student had an after school practice, coaches knew that students may have had to

attend R.O.A.R. in order to be eligible to play that week. Students may not play in their sport if

they have two or more Fs in a class. However, not many students took advantage of the

R.O.A.R. program possibly because they did not have a ride after school.

It was important to understand how students approached academic interventions both at this

school as well as at other schools. So, aside from observing and surveying the seventh graders of

the charter school, I needed to conduct a literature review for a solid research base.

Literature Review

By completing a literature review, I was able to find evidence of educators using intervention

programs to encourage positive academic achievement. I would have to, check a variety of

studies because single studies often provide inadequate evidence upon which to make

judgments (Stringer, p. 121). I would also seek to define how educators determine if an

academic program should be maintained based on its effectiveness among students.

Literature Review Questions

How do educators deem an academic intervention program successful and effective?

What forms of interventions have shown academic success among Junior High students?

What role do parents play in supporting an intervention program?

Literature Search Procedures

During my research, I used the Auraria Library using the Database List. From the Database List,

I selected the Education Subject. From there, I chose the Educational Resources Information

Center (ERIC) Database. From there, I used the keywords: interventions and Junior High School,

as well as academic achievement to find articles on my subject. I also kept my research dated

from the year 2008 to the present year, 2013.

From that search, I found articles from the School Community Journal, the Child Youth Care

Forum, the Psychology in Schools Journal, the Research in Education Journal, the European

Journal of Psychology of Education, the Journal Of Educational Research, and Behavior Analyst

Today.

Literature Review Findings

During Junior High, students undergo some of the most drastic changes physically, emotionally,

and academically. The junior high school age is oftentimes viewed as a transition time from

childhood to adulthood, yet many junior high school students are increasingly finding themselves

disconnected from the world around them (Nelson, McMahan, and Torres, 2012, p. 142). This

transitional period is crucial to a students future outlook on education, and by providing a

positive community that fosters encouraging participation in a schools community, Nelson,

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 6

McMahan, and Torres (2012) concluded that focusing solely on academics depletes a students

desire to achieve in an academic setting. The issues of high-stakes testing becoming the sole

focus of school was also echoed amongst other auxiliary school personnel: While the push for

academics is important, it is also very important for our students to like coming to school, feeling

connected and balanced in school, and motivated to achieve success in more ways than just a

test (Nelson, McMahan, and Torres, 2012, p. 138). Furthermore, by involving other outside

community members in the schools community and spirit, students begin to see value in being a

civically-minded member of society. Community involvement is a continual trend within the

literature found in this study. As Sullivan, Long, and Kucera (2011) describe with respect to

School Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS), Effective

implementation of SWPBIS relies on guidance from a leadership team comprising of the school

community who develop and implement relevant policies and practices, train staff, and provide

ongoing support and leadership for implementation effort throughout the school. Along with

administrators, general and special educators, support staff, and parents, school psychologists are

often key members of this team (Sullivan, Long, and Kucera, 2011, p. 973). Additional factors

such as staff buy-in and staff commitment to consistent practices also contribute to successful

interventions within a junior high school. These things all require a supportive community to

encourage positive change within the school. When students feel supported, they have a

considerably larger likelihood of going to school and staying in school which increases academic

achievement and lowers discipline issues. In the French study by Regner, Loose, and Dumas

(2009), students were observed to determine if academic monitoring versus academic support by

both teachers and parents influenced their achievement. The study measured academic

achievement through several factors: perceptions of parent and teacher academic involvement,

perceived competence, academic grades, and achievement goals. Academic monitoring is

defined in this study as controlling student academic behaviors such as whether they do

homework, and supervising if a student is doing his/her best. Academic support is defined as

encouraging, helping, and supporting a students academic behaviors and outcomes. The adult

would help with homework, support the student in his/her academic decisions, and supporting

them in their academic difficulties (Regner, Loose, and Dumas, 2009, p. 264). As McNeal (2012)

found, there is little evidence to support a negative reactive hypothesis in parental involvement

for student achievement, meaning that if a student is struggling with school, their parents will

become more involved in their academic monitoring. Parent involvement in a students academic

support and monitoring shows positive academic achievement.

In addition to students feeling supported by the community, if they feel successful, research

suggests that they will achieve well academically even if their perceived success is

manufactured. In Mori and Uchidas (2009) study on contrived success affecting self-efficacy

among Junior High School students, there is a correlation drawn between how good a student

feels about their academic success with their actual academic success. Interestingly enough, this

feeling seems to increase achievement as measured by test scores with no other encouragement

other than giving the student potential hope in his/her capabilities. That being said, Johnson and

Street (2012) show how a students full understanding of achievement (or lack there of) help

generate self-aware, self-advocating students who process their shortcomings through data

analysis. The Morningside Academy practices continual assessment on a daily basis (micro),

standardized testing (meta), and summative end of the unit/term basis (macro) (Johnson and

Street, 2012). When students know exactly where they are achieving based on the standards and

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 7

skills evaluation, they can understand whether they need more direct instruction, more practice,

and/or further day-to-day application of the concepts. This better equips them for knowing what

to study and even how to study. Their success is not manufactured as in Mori and Uchidas

(2009) study. Students (and their teachers, of course) know exactly how they succeeded.

While academic success is influenced by a variety of factors, motivation plays a huge role in a

students achievement. Reiss (2009) developed a School Motivation Profile (RSMP) Assessment

for 13 of the 16 Life Motives. Three of the Life Motives were deleted to avoid controversies of

asking adolescents about romance (sex), saving (money), and eating. By determining the

motivational factors among Junior High and High School students through the RMP, the team

established six reasons for low performance among students. The six reasons for low

performance in school were: fear of failure (high need for acceptance), incuriosity (low need for

cognition), lack of ambition (low need for power), spontaneity (low need for order), lack of

responsibility (low need for honor), and combativeness (high need for vengeance) (Reiss, 2009,

p. 221). When motivational factors are determined (or lack thereof), an intervention plan can be

established to promote student academic achievement.

Quality of Literature

In order to be fully reliable, I would like to see further studies conducted on Mori and Uchidas

(2009) self-efficacy research. Although their findings appear to be sound, they also appear basic

at best. They conducted their study using a graphics-based test which helped targeted students

feel positive about their manufactured achievement. Adding an additional data collection point

such as a Likert scale of success would be helpful. Their original findings appear to be more

common sense than proof that self-efficacy increases student achievement.

Although the study of students perceptions of parent and teacher academic involvement is an

important area to research, I would examine if the results of Regner, Loose, and Dumas French

study (2009) can be applied to students situations in the United States. I am unfamiliar with the

academic expectations of a French public school as compared to those in the United States.

By contrast, Reiss study (2009) on Life Motives among students has been developed as a

continuation and improvement on research that has been conducted since the 1920s. Reiss was

able to key on psychological indicators to prove on a quantitative scale when a student is

motivated to succeed in school. Within this study, I would like to see a sampling of questions

used in the RSMP survey given to students. Furthermore, I would like to see the additional

research on what types of interventions work best for the six areas of low motivation among

students.

Within the Sullivan, Long, and Kucera (2011) article, a detailed self-critique of possible

limitations gives this research strong reliability. They were able to point-out areas that may have

influenced the quantitative data presented in the study. This critical evaluation of possible

limitations really help the reader understand how to interpret their findings.

By using both a control population with similar demographics and their school population of

interest, Nelson, McMahan, and Torres (2012) are able to compare their original results with

another population to verify data, highlight outliers in their study, and understand if their

findings were supported by findings from a similar school.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 8

The level of research and detail that has gone into the Morningside Academys success is

tremendous (Johnson and Street, 2012). They have triangulated their data to determine students

success along with step-by-step evaluation of each process of learning. Their original drive and

mission is to help students who have not been success in traditional school settings because of a

variety of factors, but that does not hold them back in finding academic success. This in-depth

evaluation of the learning process is something that all schools should consider in order to

enhance teaching methods. As a private school, their model must be successful in order to

remain open as a school, and by keeping a constant vigilant eye on student data, they have an

advantage to place students where they need to be to be successful.

As McNeal (2012) researched the influence of parental involvement on a students academic

success, the study did not look at older students achievements. There are plenty of indicators

and correlations between elementary students academic success and parent involvement, but the

involvement seems to taper off as a student gets older. It is hard to say if McNeals research

thoroughly researches this facet.

Gap in Literature

Overall, it was difficult to find literature on the efficacy of after-school tutoring programs.

Initially I suppose this is because often teachers help students more on a one-on-one basis after

school rather than tracking involvement and improvement of students in after-school programs

with all teachers working in one space such as during R.O.A.R (a large scale evaluation). It was

essential to see how our mandatory intervention program (Academic Support) during school

compares with the effectiveness of the optional after-school tutoring program (R.O.A.R.).

Additionally, determining which school population is being served by these said programs helps

make the efficacy clearer. These are school-specific questions that are being answered by the

research, but they could have an impact on other schools decisions on intervention programs.

Additionally, it was important to study if possible parental involvement in and support of the

academic programs either help or hinder student achievement. Having this data for an older

selection of students is currently missing from the current available literature.

Summary of Literature Review

I was thoroughly satisfied with the variety of research available on how students are motivated

by different factors to achieve well in school. The literature also helped determine the definition

of student achievement and effectiveness of a program. Another aspect that was studied even

further was be parental involvement and support in the intervention programs. Through this

literature review, I have seen the importance of looking at this in more detail than I originally

anticipated.

Methods

Site Selection and Sampling

To determine the overall efficacy of the two intervention support programs, observations were

made on the number of students participating in both programs; as well as surveys were given to

students, parents, teachers, and the Junior High principal. Additionally, data was collected on

students grade achievements (percentages of passing grades versus Ds and Fs).

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 9

All parents received the participation consent form and surveys via email for both parents and

students via our school newsletter, which was the official form of communication for the school

(Appendix A). It was posted on the schools website for easy access.

No students were targeted for recruitment. The R.O.A.R. Program was totally voluntary after

school on Tuesdays. The students who attended Academic Support had a D or F in a class and

were assigned to attend by the teachers. This program was required regardless of the research

being conducted. The students attended during lunch and homeroom for the week they were

assigned. They could avoid being assigned to this mandatory study hall by getting their missing

assignments turned in between Wednesday, when they are assigned, and Thursday when it

occurred.

During this study, I worked with students in seventh and eighth grade at the charter school. I

collected their data regarding participation in the intervention programs on a weekly basis.

Additionally, I surveyed the students by posting the Google Doc survey online via the school

website (Appendix B). I sent out a separate Google Doc survey online via email and the school

website for parents to give feedback on the two programs offered (Appendix C). I collected data

from teachers by seeing who assigned mandatory attendance for students to Academic Support

(Appendix G) as well as offered a survey to the teachers via a Google Doc (Appendix D). I

monitored the R.O.A.R. attendance list (Appendix H) to see who came each week and what

subject they were working on. Although I collected data from and surveyed the eighth graders, I

did not evaluate this data. I worked closely with the Junior High principal of the school to get

feedback on the research being conducted. Everyone who participated in the research was sought

out intentionally for feedback. I was surprised that no teachers responded to the survey offered

despite multiple attempts for feedback.

Ethical Procedures

To ensure ethical procedures were being followed, a written consent document was issued out to

all Junior High students and parents indicating that they could refuse to participate, withdraw

from the study at any time, data regarding the study was to be shared with them, there was no

sharing of specific information (including name and grades) within the study, and all private

information was kept secured so that no one else may view it (Stringer, 2014, p. 89).

To ensure credibility, I examined data that was already collected by the institution (including

grades and intervention program attendance). Moreover, to enhance credibility, using a survey in

addition to the institutional data collected is a third source of information to provide Stringers,

Triangulation concept (p. 93). This study could be replicated in any school setting based on the

information provided to ensure dependability. There is a trail of data collected, instrument used

to, confirm the veracity of the study, providing another means for ensuring that the research is

trustworthy (p. 94).

Data Collection Methods

Research Question Data Collection Method(s) Participant(s)

1. Is providing Academic

Support an effective

intervention for 7th grade

Document grades of students the

week they are assigned to Academic

Support (Friday-Wednesday).

-Researcher, JH teachers, JH

students, JH administrator

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 10

students? Document grades of students after

they attend Academic Support

(Thursday).

Document number of students with

failing grades (weekly).

Document number of students

attending Academic Support and for

which course (weekly).

Survey participants to determine

effectiveness of the program.

2. Is providing optional

R.O.A.R. an effective

intervention for 7th grade

students?

Document number of students

attending R.O.A.R. and for which

course.

Document number of students with

failing grades who attended R.O.A.R.

versus students with passing grades.

Survey participants to determine

effectiveness of the program.

-Researcher, JH students, JH

teachers

3. Do parents find one form

of intervention better than

the other?

Survey parents (online) to determine

the effectiveness of each program.

-Researcher, JH student

parents

R.O.A.R. Attendance Students used a Google Doc Spreadsheet to sign into R.O.A.R.

each week (Appendix H).

Academic Support Teachers used a collaborative Google Doc Spreadsheet to assign

students to Academic Support each week (Appendix G).

Students were signed up whenever they had a failing grade

and/or missing assignments. Attendance was also tracked on this

document.

Grade Reports Student grades were exported from the database (Infinite

Campus) into Excel files weekly. I then calculated the grades

manually to find each students grade point average.

Grade Comparisons All data was then compiled into the final document (Appendix

I).

Opinions of Stakeholders Student Survey (Appendix B)

Parent Survey (Appendix C)

Teacher Survey (Appendix D)

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 11

Data Analysis Methods

To analyze my research questions, I gathered both qualitative and quantitative data from Junior

High students, their parents, teachers who participated in both academic programs, as well as the

Junior High principal. This information was collected through a series of surveys (Appendix B

and C).

Qualitative data reviewed was how students felt about each program, how students felt when

they were mandated to attend Academic Support, what prompted students to attend R.O.A.R.,

and how much more likely a student was to attend R.O.A.R. versus Academic Support.

Quantitative data reviewed was the number of students who attended both programs each week,

repeated student attendance (week-to-week), students assigned to Academic Support by multiple

teachers, grade fluctuation, and classes that students are in need of additional support (Appendix

G).

Initially, I wanted to sample both seventh and eighth grade data for this action research; however

there were several obstacles in collecting data that prevented me from collecting that much

information. As a result, I only processed data from the seventh graders leaving out the eighth

graders from my study. Our school database, Infinite Campus, was not able to provide grade

point averages (GPAs) for the students on a weekly basis. Each week, teachers posted progress

grades but the students GPAs were not calculated due to an unknown error in our gradebook set-

up. Therefore, I had a list of all of the 157 seventh graders grades for each week in a spreadsheet

(Appendix D). I sorted the list by grades and created a separate column with the number of

points assigned for each grade (A=4 points, B=3 points, C=2 points, D=1 points, and F=0

points). Then I resorted the worksheet by each student. I found the sum of each student's grade

points along with another column adding the number of classes each student attended. I then

divided the sum of grade points by the number of classes they took. Another complication to the

collection of data stemmed from the fact that the number of classes fluctuated for each student

This difference in classes was caused due to a number of reasons.

First of all, not all teachers had access to using Infinite Campus due to their paperwork being

held up by the school districts central office. If the teacher was hired later in the summer, they

were not given access to add grades to the grade book until even as late as the first week of

October. Secondly, if a teacher forgot to post progress grades for that week, the students were

not given a grade for that class. Finally, students were not given a grade for special education

courses such as Resource. The number of classes can not be universally calculated (8 classes for

each student) but rather had to be individually calculated.

Once the GPAs were calculated, for each week, I labeled whether the grade GPA went up, down,

or stayed the same from the previous time a grade was calculated. For example, I took the

average of their trimester GPAs from sixth grade and compared them to the GPAs from 9/13/13.

I color coded the GPA green if it went up, red if it went down, and black if the GPA didnt

change. I labeled the proceeding columns with a +1 if the GPA went up, with a -1 if the GPA

went down and a +1 if the GPA stayed the same. This allowed me to find the trends of GPAs on

a weekly basis (Appendix K, Table 1). I could also calculated the overall +/- GPA improvements

(Appendix K, Table 2).

Next, I documented whether a student attended R.O.A.R. for each week with a +1 column.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 12

Similarly, I documented if a student was assigned Academic Support and either turned in their

missing assignments before Thursdays mandatory intervention session or attended the session

itself. These categories of students both received a +1 in a different column because if they were

prompted to get their missing assignments in before Thursdays Academic Support session, then

being assigned the session was effective. It forced the students to turn in missing work and/or

gave them the time to complete the assignments during the session. I highlighted the names of

students who attended at least one form of intervention a light pink color. This allowed me to

create a final column calculating the number of students, out of the entire seventh grade, who

attended some form of intervention.

Specific data and grade comparisons could then be made for students who attended R.O.A.R. and

Academic Support (Appendix K, Tables 3-6).

Qualitative data was collected in the form of surveys to the stakeholders of this study including

students, parents, and teachers. The information was distributed through a Google Form and the

responses were compiled in a Google Spreadsheet. The responses were counted in a similar

fashion as the GPA data finding the sums of certain responses, averaging the opinions given on

likert scales, and reading for any types of trends.

Schedule

September 13th Grade sampling collected

September 17

th

ROAR sampling collected

September 19

th

Academic Support sampling collected

September 20

th

Grade sampling collected

September 24

th

ROAR sampling collected

September 26

th

Academic Support sampling collected

September 27

th

Grade sampling collected

October 1

st

ROAR sampling collected

October 3

rd

Academic Support sampling collected

October 4

th

Grade sampling collected

October 8

th

ROAR sampling collected

Draft Literature Review

October 10

th

Academic Support sampling collected

October 11

th

Grade sampling collected

October 12

th

Final Literature Review

October 15

th

ROAR sampling collected

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 13

October 17

th

Academic Support sampling collected

October 18

th

Grade sampling collected

October 21

st

Parent and Student surveys distributed online

October 31

st

Parent and student surveys collected.

November 5

th

Draft Research Findings

November 9

th

Final Research Findings

November 21

st

Presentation on Report

December 3

rd

Draft Final Action Research Report

December 7

th

Final Action Research Report

Checks for Rigor

By including a variety of perspectives and evaluative tools for all stakeholders in this research,

the findings of this research was credible (Stringer, 2014, p. 92-93). Students were observed with

data being collected from a triangulated method (surveying students, teachers, and parents on the

topic. Participants were also be debriefed and data shared with all immediate stakeholders

(students, parents, teachers, and administration) as well as with the Parent Board and school

community.

Finding ways to provide interventions is a common issue among educators (especially with

mandated programs such as Response to Interventions). Although the programs run in this

particular charter school were specific, teacher-created interventions, it is plausible that other

educators would find this research transferable to programs in place at their educational

institutions (Stringer, p. 94).

The findings of this study are outlined along with specific means of data collection, procedures,

and systematic research processes conducted to ensure dependability (Stringer, p. 94).

The artifacts collected during this action research are available to the public to verify

confirmability (Stringer, p. 94).

Findings

Among the 157 seventh graders, 57.3% of the students attended one or more session of an

intervention; either the mandatory Academic Support or elective R.O.A.R. (Appendix H). There

were 101 Academic Support passes written between 9/13/13 and 10/18/13, which includes

duplicate student attendance week by week. On the other hand, there were 68 R.O.A.R. attendees

between the same span of time also including duplicate students from week to week. Through

informal discussion, it was hypothesized by Junior High teachers and the Junior High Principal

that the GPA for students who are assigned Academic Support would be lower compared to

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 14

those who attend R.O.A.R. willingly. In this study, that hypothesis was found to be true with the

average GPA of R.O.A.R. students at 3.70 compared to Academic Support students at 2.97.

Students who attended both programs averaged a slightly higher GPA of 3.10 than Academic

Support students (Appendix H, Table 7).

Overall, students averaged a 3.38 GPA over the span of this study. One week showed a

substantial outlier. There was a tremendous dip in grades the week of 10/4/13. When looking at

the grades, I observed that a core subject teacher was not posting grades prior to the this week

due to not having access to the grade book. When the teacher did post grades, many students

were failing just that class. The cohort was able to recover pretty quickly and went back to their

typical GPAs the following week. As time passed, teachers became more consistent with posting

grades with fewer gaps in grades being posted.

When a students GPA went up, I assigned a +1 as well as a +1 for students who maintained

their GPA for the week. If a students GPA went down, I assigned a -1 point. In general, the

student body saw a +152 increase in GPA performance. These numbers are indicative of the

entire cohort population including students who did not attend any form of intervention.

Academic Support Trends

Students who were mandated to attend Academic Support due to a D and/or F in any given class

saw an increase in GPAs after attending. Of the 100 students, 52 of them saw an increase in

GPAs. This number includes repeating students from one week to the next. Only 3 of 100

students GPAs stayed the same while 45 students saw a decrease in GPA post-Academic

Support. There were more students who participated in the Academic Support program than

R.O.A.R.

R.O.A.R. Trends

Students who attended the option R.O.A.R. sessions also saw an increase in GPAs after

attending. Of the 68 students, 41 of them saw an increase in GPAs. This number also includes

repeating students from one week to the next. There were 12 of 68 students whose GPA stayed

the same while 15 students saw a decrease in GPA post-R.O.A.R.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 15

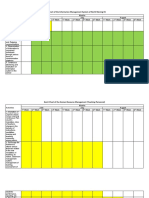

Table 8. GPA movement after attending an intervention session.

Among the 27 students who took the survey, 18 of them had attended R.O.A.R. and the majority

of them, 17, said they attended as needed. Nearly all of them said they liked the option of having

R.O.A.R. available if needed with 24 responses. Having other activities and responsibilities after

school seems to be the major reasons students do not attend with 16 responses.

Both programs had a positive effect on GPAs because the number of GPAs that went up

outnumbered the GPAs that went down. R.O.A.R. had a higher impact of GPA betterment than

Academic Support. However, as mentioned earlier (Appendix K, Table 7), the GPAs of

R.O.A.R. participants is on average much higher than Academic Support attendees. This data

helps me to classify the types of students that are participating in each program. Students are

only assigned to attend Academic Support if they have a D or an F; therefore they will have a

lower GPA due to any low grades already. Students who only attended R.O.A.R. do so with the

support of their parents as it meets after school. These students tend to do better with their

classwork strictly based on GPA. Clearly, these two forms of intervention serve two different

populations within the school.

Comparison of Research to the Literature Review

Finding similar themes in effective interventions among Junior High students and the literature

reviewed was challenging; however the most consistent theme in both arenas was motivation. In

Mori and Uchidas (2009) study on contrived success affecting self-efficacy among Junior High

School students, there is a correlation drawn between how good a student feels about their

academic success with their actual academic success. The students observed in this study also

showed they continued to succeed in their academics when they felt invited to do well. Since

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 16

students who attended the optional intervention, R.O.A.R, had better initial GPAs, they showed

motivation to succeed and used the forms of additional support provided to continue their

success. On the other hand, students who attended Academic Support were required to attend and

had the lowest GPAs in students observed. It would be interesting to give these students the same

motivational survey as conducted by Reiss (2009). He developed a School Motivation Profile

(RSMP) Assessment for 13 of the 16 Life Motives. I would like to see if the students who attend

Academic Support regular share the same motivational struggles as in Reiss study: fear of

failure (high need for acceptance), incuriosity (low need for cognition), lack of ambition (low

need for power), spontaneity (low need for order), lack of responsibility (low need for honor),

and combativeness (high need for vengeance) (Reiss, 2009, p. 221).

Another area of interest would be in parental involvement. Parents were offered the opportunity

to respond to a survey regarding both programs. Only three of the eleven parents who

participated in the survey had seventh grade students. The overall opinion of the parents of both

programs was positive with gratitude that both programs existed for their students. One parent

stated, I think it is nice to have a time when the kids can get more help if needed, especially for

seventh graders. Buy-in of the two intervention programs among these surveyed parents was

high; however there were very few participants to offer a thorough overarching opinion. The

students who struggle with academics did not necessarily have parental involvement in the

survey, so as research suggests, when parental involvement is high both in a students academic

support and monitoring shows positive academic achievement (McNeal, 2012).

Limitations

As with any form of research being conducted, there are limitations to the study. Initially, there

is the source of error possibility in grade point average (GPA) calculation. The schools student

database and grade book system, Infinite Campus, was not able to produce a weekly GPA for

each student. It would only provide grades for each course. Most students have an eight class

schedule with the standard A-F grading system for each class. However, some students who

require additional support through an IEP, 504, or other Special Education class may not have an

eight period schedule. So there was no standard way of calculating GPAs; it was done manually

with the help of spreadsheet software. For the end of the quarter grades, students (with the help

of their teachers) calculated their own GPAs during Pride Time (Appendix I). I went back and

double checked each students GPA in my own Pride Time and found mathematical errors by the

students. To avoid such an issue, having an automated program to handle GPA calculation would

be ideal.

Another form of limitation during this study was ensuring that all students were tracked

accurately. These academic interventions can be a little hectic at times, and it is impossible to

ensure that all students signed in (attendance) during each session. Students are learning how to

use things such as cloud-based documents that allow multiple people to work at once. So, it was

necessary to check and make sure that no ones names were deleted while another student signed

in on another computer. If they were not signed in, it was not documented that they attended the

intervention session and their GPA was not monitored for improvement.

Although this research is specific to a particular charter school, the after school programs

described in this research are similar to those offered at other junior highs. Therefore this

information and research can be translated to other schools and programs. The findings can help

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 17

the future of this particular schools programs and efficiency of programs. By describing the

efficacy of these programs, other educators and administrators can understand what has been

done and how it worked in the past among seventh and eighth graders.

Implications of Practice

As a result, the efficacy of both Academic Support and R.O.A.R. are beneficial for students of

the Junior High at this charter school in Westminster, Colorado. Although attendees of R.O.A.R.

showed a greater increase in GPAs, there was still an increase in GPAs among students who

attended the mandated Academic Support. Both programs serve different student populations of

the school and allow for an opportunity to get additional support outside of the traditional

classroom setting. During a time when organization and transition is difficult, these interventions

seem to have a positive outcome among the students. As a student responded, I think that both

options are great for the students. First, R.O.A.R gives you the opportunity to meet with all

teachers. This is a positive. The negative is that it is after-school so difficult for those in clubs or

sports. That is why Academic Support is great to have available when the after-school choice is

not an option.

These findings lead me to the conclusion that both programs should be retained while explaining

to parents and students that the efficacy of R.O.A.R. seems to be higher. This suggests that

because it requires parental buy-in in order for students to stay after school, parental support is

another key element to a students overall success in school. It also suggests that student self-

motivation is an important factor in academic success.

Impact (Negative and Positive)

A positive impact of this research was to find the most effective form(s) of interventions to better

serve the students in their needs. We could also increase the amount of passing students (fewer

Ds and Fs). Lastly, we could focus our limited resources on the most effective interventions,

which may be a continuation of both programs. A negative impact of this research could have

been that students feel like they were being targeted for questioning based on their grades.

However, I made every effort to assure students of their anonymity, and explain that their

feedback was being used to help make the study hall programs better for them and future

students. Doing this research rather than another form of research may not have been beneficial

and may have taken away time and energy from looking into another area of study.

Summary of Research

The overall focus of this research was to help determine which intervention programs were most

effective and needed for students at the Junior High level of a charter school in Colorado. By

determining which program helped students most (better grades, better study habits, self-

advocacy developed), teachers and administration could determine where to use manpower most

efficiently.

It is quite possible that both interventions were necessary within this particular school

environment, because R.O.A.R. tends to attract good students while Academic Support is a

mandatory program for failing students. Each provided the same assistance for different

populations of students. However, with both qualitative and quantitative data collected, this

outcome can be confirmed or denied. Also, it could be observed if students were more likely to

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 18

succeed in Junior High if they attend R.O.A.R. regularly as opposed to Academic Support. This

coincided with the schools Strategic Plan goal of having 80% of students achieving a 3.0 GPA

this year.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 19

References

Johnson, K., and Street, E. M. (2012). From the laboratory to the field and back again:

Morningside Academy's 32 years of improving students' academic performance.

Behavior Analyst Today, 13(1), 20-40.

McNeal, R. r. (2012). Checking in or checking out? Investigating the parent involvement

reactive hypothesis. Journal Of Educational Research,105(2), 79-89.

Mori, K., and Uchida, A. (2009). Can contrived success affect self-efficacy among junior

high school students? Research In Education, 82(1), 60-68.

Nelson, L. P., McMahan, S. K., and Torres, T. (2012). The impact of a junior high school

community intervention project: Moving beyond the testing juggernaut and into a

community of creative learners. School Community Journal, 22(1), 125-144.

Regner, I., Loose, F., and Dumas, F. (2009). Students' perceptions of parental and teacher

academic involvement: Consequences on achievement goals. European Journal Of

Psychology Of Education, 24(2), 263-277.

Reiss, S. (2009). Six motivational reasons for low school achievement. Child and Youth

Care Forum, 38(4), 219-225.

Stringer, E. (2014). Action research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications,

Inc.

Sullivan, A. L., Long, L., and Kucera, M. (2011). A survey of school psychologists'

preparation, participation, and perceptions related to positive behavior interventions and

supports. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 971-985.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 20

Appendices

A. Participation Consent Form

Dear Academy Junior High Community,

I am conducting some action research on the two study hall programs offered at the Junior High

levelAcademic Support, which is offered during school and Reinforcement of Academic

Responsibility (a.k.a. R.O.A.R.), which is offered after school. I am researching the effectiveness

of each study hall program with respect to student grades. It is a requirement for one of the

graduate courses in which I have enrolled at the University of Colorado, Denver. I am enrolled in

this course and conducting this research so I can continue to refine my practice and provide my

students with the best possible teaching.

If you decide to participate in this study, you will be asked to complete an online survey that will

take around 15 minutes. There are no right or wrong answers. Your individual answers to the

questions will not be identified or published. You may discontinue your participation in this

study at any time without penalty.

Answering and completing these online questionnaires indicate your willingness to participate in

this study. Findings will be reported back to the community via the school newsletter, The

Wildcat Pause as well as on the schools website. Clicking below indicates that you have read

and understood the description of the study and you agree to participate.

If you have any further questions you may contact me, the Principal Investigator, via email at

joy.vigil@theacademyk12.org or by phone at 303.289.8088 x 138 or my instructor, Jennifer

VanBerschot, at jennifer.vanberschot@ucdenver.edu.

Thank you for your time,

Joy E. Vigil

Secondary Visual Arts Teacher

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 21

B. Student Survey

C. Parent Survey

D. Teacher Survey

E. Literature Log Review

Date of

Search

Database Keyword

Search

Journal + Article

Name

Summary

10/02/13 ERIC interventions

junior high

school

School Community

Journal, 2012, Vol.

22, No. 1

The Impact of a

Junior High School

Community

Intervention Project:

Moving Beyond the

Testing Juggernaut

and Into a

Community of

Creative Learners

By implementing a community

intervention project, this study

tracked social support,

responsibility among students,

school climate, self efficacy, and

optimism of students. The

community, parents, and students

were encouraged to be active

participants in the school for two

years. Results of this research

found that when the schools

focus was solely on high-stakes

test scores, student engagement

and participation went down. On

the other hand, when community

development was encouraged,

those items being tracked

increased positively.

10/02/13 ERIC interventions

junior high

school

Child Youth Care

Forum (2009) 38

Six Motivational

Reasons for Low

School Achievement

Motivation is a huge element in

student success and this research

studies six reasons for low

motivation among Junior High

and High School students. The

motivational factors include,

fear of failure (high need for

acceptance), incuriosity (low

need for cognition), lack of

ambition (low need for power),

spontaneity (low need for order),

lack of responsibility (low need

for honor), and combativeness

(high need for vengeance) (p.

221). With further evaluation of

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 22

these factors, appropriate

interventions can be established

and implemented to help

students achieve academically.

10/02/13 ERIC interventions

junior high

school

Psychology in the

Schools, Vol. 48(10),

2011

A Survey of School

Psychologists

Preparation,

Participation, and

Perceptions Related

to Positive Behavior

Interventions and

Supports

This research studies the use of

a School Wide Positive Behavior

Interventions and Supports

(SWPBIS) and its impact on

various factors: disruptive

behaviors, school climate, staff

job satisfaction, and academic

interventions. The study

highlights the keys to an

effective intervention [defining

effective].

Study never official defines what

SWPBIS are and expect survey

participants to understand what

this model is with no further

explanation.

10/08/13 ERIC academic

success

junior high

school

Research in

Education, v82 n1

Can Contrived

Success Affect Self-

Efficacy among

Junior High School

Students?

Using the fMORI technique to

test students, this study

determines how a Junior High

student can predict their success

based on their perceived ability.

When a student experienced an

enhanced sense of capability,

they performed noticeably better

than other students who did not

experience this success.

10/08/13 ERIC academic

success

junior high

school

European Journal of

Psychology of

Education

2009. Vol. XXIV. n'2

Students' perceptions

of parental

and teacher

academic

involvement:

Consequences on

This research shows that a

students perceived involvement

of parents and teachers has a

direct correlation to engagement

and success in academic tasks.

Whether an adult is engaged in

academic support or academic

monitoring, students see how the

adult values education and

develops this idea in his/her own

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 23

achievement goals academic career.

10/12/13 ERIC academic

achievement

junior high

Journal Of

Educational

Research,105(2), 79-

89

Checking in or

checking out?

Investigating the

parent involvement

reactive hypothesis

Parental involvement (or lack

thereof) directly and indirectly

impacts how social class

advantages (or disadvantages)

pass from one generation to the

next. Theres both positive and

negative research indicating how

parent involvement influences

student achievement. Parental

involvement can have a negative

impact when the involvement is

reactionary to the student already

having problems in school.

10/12/13 ERIC academic

achievement

junior high

Behavior Analyst

Today, 13(1)

From the laboratory

to the field and back

again: Morningside

Academy's 32 years

of improving

students' academic

performance

The Morningside Academy uses

a continual evaluative process

while educating Elementary and

Junior High students. They

research best practices in

education to determine which

methods would be best to

implement in teaching. Overall,

the students embark on a three

phase process of learning:

instruction, practice, and

application. Students are

assessed in three ways: macro,

meta, and mirco. Each test

provides data to better

understand the students needs

for instruction. Additionally

important, students are taught to

self-evaluate to encourage self-

awareness of needs and

advocacy.

F. Grade Comparison Document

G. Academic Support Worksheet Example

H. R.O.A.R. Attendance Worksheet Example

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 24

I. GPA Calculation Worksheet

J. Data Collection

G.P.A. Criteria 7th Grade 3.0 and Above

9/13/13 125

9/20/13 118

9/27/13 116

10/4/13 91

10/11/13 113

10/18/13 113

R.O.A.R. Attendance 7th Grade

9/17/13 6

9/24/13 7

10/1/13 13

10/8/13 23

10/15/13 19

Academic Support Attendance 7th Grade

9/19/13 34

9/26/13 9

10/3/13 25

10/10/13 29

10/17/13 4

Average

G.P.A.

7th Grade

R.O.A.R.

7th Grade

Academic

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 25

Support

Week 1 3.52 3.08

Week 2 3.58 3.11

Week 3 3.34 3.05

Week 4 3.02 2.37

Week 5 3.48 2.24

K. Tables of Findings

Table 1. Measures the GPA of seventh graders on a weekly basis starting with their overall GPA

from sixth grade as a starting point.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 26

Table 2. Measures the overall +/- of GPAs per week.

Table 3. Measures the average GPA for students who attended R.O.A.R.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 27

Table 4. Measures the average GPA for students who attended Academic Support.

Table 5. Measures the number of GPAs that either go up, go down, or stay the same each week

after attending R.O.A.R.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 28

Table 6. Measures the number of GPAs that either go up, go down, or stay the same each week

after attending Academic Support.

Table 7. Measures the average GPAs of students who attended interventions.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR JUNIOR HIGH STUDENTS 29

Table 8. GPA movement after attending an intervention session.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Assessment Psychology TestingDokumen56 halamanAssessment Psychology TestingBal Krishna TharuBelum ada peringkat

- Leap 2025 Mathematics Practice Test GuidanceDokumen15 halamanLeap 2025 Mathematics Practice Test GuidanceimeBelum ada peringkat

- Feb 26 Chapter 1-5 (Analysis of Academic Performance of Regular Students and Student Assistants of Jose Rizal University) PDFDokumen113 halamanFeb 26 Chapter 1-5 (Analysis of Academic Performance of Regular Students and Student Assistants of Jose Rizal University) PDF蔡 クリス100% (1)

- Pre Oral DefenseDokumen43 halamanPre Oral DefenseNiña Nerie Nague DomingoBelum ada peringkat

- Equipment Criticality AnalysisDokumen20 halamanEquipment Criticality Analysisprsiva242003406650% (6)

- Alternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportDari EverandAlternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportBelum ada peringkat

- The IELTS Writing Assessment Revision ProjectDokumen295 halamanThe IELTS Writing Assessment Revision ProjectArdianaBelum ada peringkat

- ATI Acute ProctoredDokumen6 halamanATI Acute Proctoredyoderjess425Belum ada peringkat

- Reflection in DELM 112 - Social-Psychological and Philosophical IssuesDokumen2 halamanReflection in DELM 112 - Social-Psychological and Philosophical IssuesSonny Matias100% (4)

- A Study of Academic Achievement Among High School Students in Relation To Their Study HabitsDokumen14 halamanA Study of Academic Achievement Among High School Students in Relation To Their Study HabitsImpact Journals100% (3)

- Dlbbaaiwb01 e Course BookDokumen140 halamanDlbbaaiwb01 e Course BookPandu100% (1)

- DLL Math 10 q2Dokumen10 halamanDLL Math 10 q2Cyrah Mae RavalBelum ada peringkat

- Written Exam ReviewerDokumen5 halamanWritten Exam ReviewerTintin Frayna GabalesBelum ada peringkat

- Instructional Leadership Action PlanDokumen15 halamanInstructional Leadership Action Planapi-261844107100% (3)

- FINAL RESEARCH Mam Shellamarie and ZenaidaDokumen23 halamanFINAL RESEARCH Mam Shellamarie and ZenaidaJosenia ConstantinoBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Home Based Activity For MAED: Cebu Technological University Cebu CityDokumen14 halamanAssignment Home Based Activity For MAED: Cebu Technological University Cebu CityZurchiel LeihcBelum ada peringkat

- PCP PlanDokumen28 halamanPCP Planapi-283964589Belum ada peringkat

- Jo Action ResearchDokumen8 halamanJo Action ResearchAnton Naing100% (2)

- Lesson 4-5 Activities and ExercisesDokumen28 halamanLesson 4-5 Activities and ExercisesKathya Balani Nabore100% (3)

- DiscussionDokumen6 halamanDiscussionapi-497969725Belum ada peringkat

- Summary, Findings, Conclusion and RecommendationDokumen4 halamanSummary, Findings, Conclusion and RecommendationElijah PunzalanBelum ada peringkat

- Reported Study Habits For International Students (SR-SHI) Used To Identify At-Risk Students inDokumen7 halamanReported Study Habits For International Students (SR-SHI) Used To Identify At-Risk Students inNeil Jasper Buensuceso BombitaBelum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal TallmanDokumen8 halamanResearch Proposal Tallmanapi-263365115Belum ada peringkat

- Manual Research Project B.Ed (1.5 Year/2.5 Year) : Course Code: 8613Dokumen28 halamanManual Research Project B.Ed (1.5 Year/2.5 Year) : Course Code: 8613Muhammad TahirBelum ada peringkat

- Standard 1 DesantisDokumen7 halamanStandard 1 Desantisapi-241424416Belum ada peringkat

- Data Board InquiryDokumen16 halamanData Board InquirylynjonesBelum ada peringkat

- pRACTICAL RESEARCH SAMPLEDokumen9 halamanpRACTICAL RESEARCH SAMPLERudy, Jr MarianoBelum ada peringkat

- Ero Pacific Learners LeafletDokumen4 halamanEro Pacific Learners Leafletapi-319572366Belum ada peringkat

- 5 Research AbstractDokumen4 halaman5 Research AbstractKryshia Mae CaldereroBelum ada peringkat

- The Five Attributes of Successful SchoolsDokumen13 halamanThe Five Attributes of Successful SchoolsJanet AlmenanaBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter Two SettingDokumen7 halamanChapter Two SettingmelissahanBelum ada peringkat

- Graduate KSC 2015Dokumen4 halamanGraduate KSC 2015api-296342044Belum ada peringkat

- CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCDokumen5 halamanCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCLyrazelle FloritoBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of the Positive Behavior Support Program on Fourth-Grade Student Discipline InfractionsDari EverandEvaluation of the Positive Behavior Support Program on Fourth-Grade Student Discipline InfractionsBelum ada peringkat

- Uconn Dissertation FellowshipDokumen8 halamanUconn Dissertation FellowshipBuyAPaperUK100% (1)

- Study Habits of Grade V PupilsDokumen36 halamanStudy Habits of Grade V PupilsNolxn TwylaBelum ada peringkat

- (New) PERCEPTIONS OF TEACHERS IN SANMUEL NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLDokumen20 halaman(New) PERCEPTIONS OF TEACHERS IN SANMUEL NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLIvan LopezBelum ada peringkat

- DialnetDokumen19 halamanDialnetzoeBelum ada peringkat

- RESEARCH ORIGINAL (With Page)Dokumen51 halamanRESEARCH ORIGINAL (With Page)Athena JuatBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen24 halamanChapter 1Percy JacksonBelum ada peringkat

- LEO Group 7Dokumen21 halamanLEO Group 7Mariecriz Balaba BanaezBelum ada peringkat

- IntroductionDokumen19 halamanIntroductionLovely BesaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study Mid-Term Assignment DueDokumen7 halamanCase Study Mid-Term Assignment DuewaterleafplumbingllcBelum ada peringkat

- Aristotle Group3 Lariosa Factors Affecting Study Habits of Senior High School StudentsDokumen15 halamanAristotle Group3 Lariosa Factors Affecting Study Habits of Senior High School StudentsKathleenjoyce BongatoBelum ada peringkat

- Cook RevisedpaperDokumen22 halamanCook Revisedpaperapi-300485205Belum ada peringkat

- RESEARCH 201 Gwapa KoDokumen4 halamanRESEARCH 201 Gwapa KoJanice Alsula-Blanco Binondo100% (1)

- The Factors Affecting The StudentDokumen4 halamanThe Factors Affecting The StudentAsad AliBelum ada peringkat

- School Resources For Learning NarrativeDokumen19 halamanSchool Resources For Learning NarrativeyhsstaffBelum ada peringkat

- Final ThesisDokumen43 halamanFinal ThesisEfren GuinobanBelum ada peringkat

- A Literature Review of Academic PerformanceDokumen12 halamanA Literature Review of Academic PerformanceYssay CristiBelum ada peringkat

- Students With ADHD - Can They Find Success in The ClassroomDokumen36 halamanStudents With ADHD - Can They Find Success in The ClassroomChristine CamaraBelum ada peringkat

- DocumentDokumen5 halamanDocumentThea Margareth MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- GAS12Bentley Group1 Chapter1 2 3 3Dokumen29 halamanGAS12Bentley Group1 Chapter1 2 3 3sheilaBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact Student Behavior Has On LearningDokumen26 halamanThe Impact Student Behavior Has On LearningAlvis Mon BartolomeBelum ada peringkat

- Action Research Proposal - ZNHSDokumen15 halamanAction Research Proposal - ZNHSJOHN PONCE GALMANBelum ada peringkat

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Adm/modular Versus Formal School of Grade 10 Students in Lecheria National High School S.Y. 2018-2019Dokumen20 halamanAdvantages and Disadvantages of Adm/modular Versus Formal School of Grade 10 Students in Lecheria National High School S.Y. 2018-2019Sophia OropesaBelum ada peringkat

- Berman Risa How Mandates and Testing Has Affected Teachers and StudentsDokumen9 halamanBerman Risa How Mandates and Testing Has Affected Teachers and Studentsapi-285314046Belum ada peringkat

- Final Par ReportDokumen27 halamanFinal Par Reportapi-255210701Belum ada peringkat

- WCES 2014 SI Plan January Submission Part 2 SchoolwideDokumen24 halamanWCES 2014 SI Plan January Submission Part 2 SchoolwidecrissyjolleyBelum ada peringkat

- IST 661: Assignment 1Dokumen10 halamanIST 661: Assignment 1api-299675334Belum ada peringkat

- Neslie 2023 074114Dokumen27 halamanNeslie 2023 074114sanchezryanpoorBelum ada peringkat

- A Comparative Analysis Between Traditional and Progressive Sped School Settings in Curriculum, Facilities and InstructionsDokumen10 halamanA Comparative Analysis Between Traditional and Progressive Sped School Settings in Curriculum, Facilities and InstructionsAngeli Gabrielle Q. TalusanBelum ada peringkat

- Richard Kwabena Akrofi Baafi - Summary - BaafiDokumen16 halamanRichard Kwabena Akrofi Baafi - Summary - BaafiEdcel DupolBelum ada peringkat

- MethodsDokumen7 halamanMethodsapi-432839239Belum ada peringkat

- Outcomes Early Childhood Education Literature ReviewDokumen8 halamanOutcomes Early Childhood Education Literature ReviewxmniibvkgBelum ada peringkat

- The Effects of Alcohol To The Academic Performance of Senior High School StudentDokumen9 halamanThe Effects of Alcohol To The Academic Performance of Senior High School Studentjohn taylorBelum ada peringkat

- Global IssuesDokumen21 halamanGlobal IssuesClariz VelascoBelum ada peringkat

- Full Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Dokumen4 halamanFull Length Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926sudhakar samBelum ada peringkat

- "Man-Up" Institute Guide: Motivating Attitudes That Nurture an Understanding of Your PotentialDari Everand"Man-Up" Institute Guide: Motivating Attitudes That Nurture an Understanding of Your PotentialBelum ada peringkat

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsDari EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsBelum ada peringkat

- Inquiry Quest Calendar 2017Dokumen1 halamanInquiry Quest Calendar 2017JoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Joy Vigil-Change ProjectDokumen9 halamanJoy Vigil-Change ProjectJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Project 4.5 Review Redesign AdvertDokumen4 halamanProject 4.5 Review Redesign AdvertJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Project 4.2 Project PlanDokumen3 halamanProject 4.2 Project PlanJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Project 2.5 How To Use Painting ToolsDokumen8 halamanProject 2.5 How To Use Painting ToolsJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Project 2.2 How To Color ManagementDokumen4 halamanProject 2.2 How To Color ManagementJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- Project 2.1 Design PrinciplesDokumen2 halamanProject 2.1 Design PrinciplesJoyVigilBelum ada peringkat

- 56 239 1 PBDokumen11 halaman56 239 1 PBahmad acengBelum ada peringkat

- Ubd - ExplorationDokumen5 halamanUbd - Explorationapi-273737279Belum ada peringkat

- Listening Skill Language InstructionDokumen2 halamanListening Skill Language InstructionAinul MardhyahBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 9 Music Module 3Dokumen18 halamanGrade 9 Music Module 3Zet A. LuceñoBelum ada peringkat

- Diversity in The Classroom - Learners With High - Incidence DisabilitiesDokumen11 halamanDiversity in The Classroom - Learners With High - Incidence DisabilitiesCherry Ann JuitBelum ada peringkat

- AQTF 2005 RTO StandardsDokumen28 halamanAQTF 2005 RTO StandardsGarth SchumannBelum ada peringkat

- In The Hall of The Mountain King 2Dokumen9 halamanIn The Hall of The Mountain King 2api-356110158Belum ada peringkat

- Ued495-496 Brammer Cheyenne Rationale and Reflection Planning Preparation Instruction and AssessmentDokumen6 halamanUed495-496 Brammer Cheyenne Rationale and Reflection Planning Preparation Instruction and Assessmentapi-384349223Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan For Violence PreventionDokumen8 halamanLesson Plan For Violence Preventionapi-606079554Belum ada peringkat

- Persuasive Writing Task SheetDokumen6 halamanPersuasive Writing Task SheetS TANCREDBelum ada peringkat

- Teacher Work Sample 2-1Dokumen16 halamanTeacher Work Sample 2-1api-248707949Belum ada peringkat

- Assessment Schedule 2018Dokumen8 halamanAssessment Schedule 2018api-400088384Belum ada peringkat

- Alternative AssessmentDokumen12 halamanAlternative AssessmentlhaiticuasBelum ada peringkat

- Gantt Chart of The Information Management System of North Marinig ESDokumen10 halamanGantt Chart of The Information Management System of North Marinig ESFrancis JastillanaBelum ada peringkat

- Citizenship Education Training Manual UpdateDokumen22 halamanCitizenship Education Training Manual Updategamedas100Belum ada peringkat

- Math Lesson Plan - Cartesian Plane 2Dokumen2 halamanMath Lesson Plan - Cartesian Plane 2api-337393538Belum ada peringkat

- Gts PosterDokumen1 halamanGts Posterapi-333550548Belum ada peringkat

- Level 3 Sup Lesson Plan 1 3Dokumen10 halamanLevel 3 Sup Lesson Plan 1 3api-644489273Belum ada peringkat

- Monroe SurveyDokumen10 halamanMonroe SurveyXian Zeus VowelBelum ada peringkat

- Educ 214 (Yeba)Dokumen3 halamanEduc 214 (Yeba)Francine Kate Santelli YebanBelum ada peringkat