Thomas Ligotti Interviewed (2011) + Jean Ferry Tale

Diunggah oleh

Ryan RodeJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Thomas Ligotti Interviewed (2011) + Jean Ferry Tale

Diunggah oleh

Ryan RodeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

# Nov 8, 2011

Interviews

Exclusive Interview: Thomas Ligotti on Weird Fiction

Includes Ligotti's top picks for under-appreciated weird fiction!

Thomas Ligotti (1953 ) is an iconic American writer of weird short fiction whose oeuvre

has been as ground-breaking as, if not always as well-acknowledged as, that of Edgar Allan

Poe, Franz Kafka, and H.P. Lovecraft. His first collection, Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1986),

is an outright classic in the field, with a subsequent compilation from several collections, The

Nightmare Factory (1997), cementing Ligottis reputation. The influence of workplace

experiences infused Ligottis fiction with fresh energy, resulting in the masterpiece My Work

Here Is Not Yet Done (2002). The Town Manager (2003), which we reprinted in our The

Weird, showcases Ligotti in this phase of his writing. An underlying dark sense of humor is

more prevalent in his fiction generally than is acknowledged by most critics, which becomes

clear in the interview.

Two of the stories cited by Ligotti below are featured on WFR.com this week: Algernon

Blackwoods classic The Willows and, in a new translation by Edward Gauvin, the Jean

Ferry story on Ligottis list of under-appreciated weird stories/writers.

Ligotti tells us that this is the first time that he has been asked specifically about weird

fiction, let alone did a whole interview on it. On a personal note, one of our most prized

possessions is the hardcover In a Foreign Town, in a Foreign Land by Thomas Ligotti, with

soundtrack by Current 93, pictured above. - Ann & Jeff VanderMeer

Weirdfictionreview.com: What writers were your introduction to the weird, whether the

Weird Tales kind of weird or something stranger?

Ligotti: The first story I read that is usually classed as a specimen of weird fiction was

Arthur Machens The Great God Pan. I didnt fully understand the story, but I felt

immediately captivated by it. There was a real whiff of evil behind the events of the narrative.

I then read other stories by Machen The White People, The Three Impostersand

sensed that I had found a world where I belonged: a kind of degenerate incarnation of the

Sherlock Holmes tales I loved so much. Immediately after reading Machen, I read Lovecraft

and recognized the resemblance between the two authors, no doubt because Lovecraft was

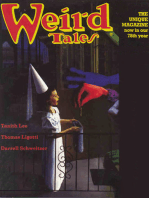

influenced by Machen. I was never enamored of the Weird Tales writers. There was nothing

distinctive in their style, and their plots were embarrassingly conventional. Lovecraft wrote in

one of his letters that he felt that writing for Weird Tales had a detrimental effect on the style

of his later stories, and I think he was right. Not that these stories were not brilliant in their

conception and imagination, but they had lost a poetic quality present in his earlier stories. By

the early 1980s I had read practically every horror/weird/ghost writers there was to read. And

by that time I had already begun to read foreign writers of every nationality in translation.

These were mostly Symbolist and Decadent writers as well as writers influenced by these

nineteenth-century literary and artistic movements. What these and subsequent authors

I consumed had in common was a temper of pessimism, whether it was overt or implicit.

Around the early 1990s, I had stopped reading horror stories altogether, unless someone sent

me something they wanted me to read or a publisher was kind of enough to supply me with

a free copy of a book they had just published. For a while I became interested in the

uncanny, which accounts for my use of this concept in The Conspiracy against the Human

Race. Quite a number of literary critics and European philosophers have taken an interest in

the facets of meaning suggested by the uncanny, which I consider to be interchangeable with

the weird. In fact, if I had to use a word that most accurately describes most of my own

stories, it would be uncanny.

WFR: Do you see a difference between horror and the weird and even if so, is the

difference important?

Ligotti: I think that if it werent for Lovecrafts Supernatural Horror in Literature, no one

would ever have thought in terms of the weird, which is used copiously throughout his

1927 monograph. This is rather odd since the subject matter of the work is designated in its

title as supernatural horror. On occasion Ive thought in terms of the weird without being as

invested in it as much as Lovecraft. I once wrote an essay titled In the Night, In the Dark:

A Note on the Appreciation of Weird Fiction. Toward the end of this piece, I asserted: By

definition the weird story is based on an enigma that can never be dispelled. Semantics

aside, the important thing to me in a so-called weird tale is an impenetrable mystery that

generates the actions and manifestations in a narrative. A good example is Lovecrafts

favorite weird story The Willows by Algernon Blackwood. Theres nothing in the willows

themselves that is responsible for the phenomena that menace the two men who stop on an

island while boating down the Danube. The willows are only a symbol of some invisible,

unknowable force that means no good to those who are unfortunate enough to be caught by

bad weather in this atmospheric locale. This force is patently supernatural or, given

Blackwoods view of nature, preternatural but it need not be. In Poes The Tell-Tale

Heart, the narrator can explain his motive for killing the old man only because there is

something about one of his eyes that maddens him to murder. Again, there is an enigma at the

heart of the story, a mystery that cannot be solved and that keeps the story alive. With horror

stories, its the exact opposite: there must be a legend for the horrific goings-on and this

legend must be revealed in the story or movie, even if the explanation is rather vague.

Example: Something must have gone wrong with the laboratory experiments they was doin

on them monkeys that made em so ferocious and 28 days later infected almost everyone and

turned em into those zombie things that run around like nobodys business. Horror legends

are endlessly reusable and have a logical or pseudo-logical explanation. Weird narratives are

usually one of a kind and leave an enigma behind them. Thats the difference I see between

horror and the weird.

WFR: When the weird in weird fiction fails for you, whats usually the reason?

Ligotti: I believe that if a work of weird fiction fails the reason for its failure is that the

author is innocent of the emotional states and experiences that are necessary if one is to

conjure a sense of the weird in the reader. Without question, Lovecraft was possessed of the

emotional states and experiences required for writing superb weird fiction. And it wouldnt

be going out on a limb to surmise that they were indicative of an unhealthy psychology in

Lovecrafts case. In fact, I would say that to be a successful weird writer, it cant hurt to be

afflicted with one mental ailment or another. There are numerous cases in which weird fiction

writers suffered from some pathology, and when the pathology isnt the stuff of legend as

in the instance of Poe it may be something that has simply never been exposed. Personally,

Im utterly perplexed why anyone would want to write weird fiction without being at least

a little over the edge, if not a basket case. Of course, it may be that there are no such

individuals. Ultimately, I dont think its a matter of weird fiction that fails as it is of weird

fiction that differs in type and is not to a given readers taste. (One factor that contributes to

a liking for one weird writer over another is prose style, a characteristic that has made

Lovecraft a favorite for some and a joke for others.) Certain weird writers are obviously

preoccupied by obsessions that mean nothing to others. Nevertheless, the all-important

ingredient in every weird writer is that of having been born in the vicinity of mental

institutions the world over. This line of argument is naturally subject to dispute. My opinion

is based on personal emotional states and experiences that seem conspicuous to me in my

fellow weird writers.

WFR: Frankly, The Town Manager is one of dozens of stories from you we could have

included in The Weird. What drew us to it in part was a kind of dark sense of humor

underlying the story, possibly better expressed as absurdism rather than humor. Do you

see any of your stories as humorous, albeit in a dark way?

Ligotti: Im quite aware of the humor not only in my stories but also in the stories of many

authors I admire. Nabokovs fiction is uniformly comic, although the endings of his stories

and novels are usually grim, sad, or spooky in some way. The same could be said of Gogol,

who was a big influence on Nabokov. Stories like The Overcoat and The Nose are comic

nightmares. Bruno Schulz wrote highly weird stories in which humor was essential and

natural. In the work of all three of these authors humor was organic to their purpose. It wasnt

an element injected into a given narrative in order to provide laughs in the manner of a low-

budget horror movie. In contrast, Poe wrote some stories that were intended to be purely

comical. These he designated as grotesques. His weird stories, which called arabesques,

are always serious from beginning to end. Some critics would call them self-serious or

parodic of the Gothic fiction of the day. Lovecraft also made a strict distinction between the

few humorous pieces he wrote and his weird fiction. I like to think that the kind of humor in

my own stories is integral to their weirdness. But at the time of writing, Im not consciously

trying to produce a concoction of humor and weirdness (or horror or the uncanny). Even

though Im writing a weird story, I want it to be all of a piece. I wouldnt want anything

humorous in the story to undermine the story as a whole, which is definitely not supposed

to funny.

WFR: Is there such a thing as too weird? What does too weird mean to you when

someone says it about your own work?

Ligotti: When someone says that something Ive written is too weird, I take it to mean that

they didnt enjoy what they read. Why else would someone who likes weird fiction consider

a story too weird? I do my best to make my stories work on two levels. On a superficial level,

I want to tell an enjoyable weird story. On a deeper level, I want to write a story that is

enigmatic in the way I mentioned above. The example I gave was Poes Tell-Tale Heart.

Another story by Poe that works on two levels is The Fall of the House of Usher. On first

reading, this story seems to make all the sense in the world. But the more you think about it,

the more you say to yourself, What the hell was that story about? Its on the first level that

I think a story of mine might be considered too weird. Ive had people write to me and ask

what some part of a story was supposed to mean. This usually has to do with the deeper level

of a story. Sometimes, though, I realize that I could have given more clarity to either the

superficial or the deeper level of the story. Nevertheless, its still possible to write

a hypnotically appealing story without the reader understanding it either literally or

symbolically. Think of Kafka. And the whole of Bruno Schulzs output consists of stories

like this. Over the past few years, Ive had the good fortune to revise the stories of my first

three collections. And while many of the changes were technical or stylistic, I also altered

some stories to emphasize their sense in part or as a whole. I remember reading that T.E.D.

Klein rewrote his great novella The Events at Poroth Farm every time it was reprinted,

which was often. Ramsey Campbell said the same thing about revising whole collections of

his stories, at least the early collections, when they were reprinted. Then, of course, theres

the striking case of Henry James, who rewrote thirty-five volumes for the definitive edition of

his works. And speaking of Henry James, Jorge Luis Borges once wrote: I have visited some

literatures of the East and West; I have compiled an encyclopedic anthology of fantastic

fiction; I have translated Kafka, Melville, and Bloy; I know of no stranger work than that of

Henry James. If nothing else, Borges makes the case that weirdness is in the mind of the

beholder. Who else but Borges would say that he knew of no stranger work than that of

Henry James? On the other hand, if you think of Jamess Turn of the Screw, you may begin

to understand what Borges means. To my mind, its impossible to read this novella without

thinking that James somehow botched the narrative in such a way that from the time it was

published in 1898 to the present, no reader or critic has been able to produce a universally

credible reading of it. I analyzed and annotated every page of Turn of the Screw and went

away defeated. I think that says it all regarding stories that someone might consider too

weird. That is, unless one wants to get into the fiction of the Symbolists, the Futurists, the

Surrealists, or any number of modern and post-modern writers.

WFR: Whats the weirdest piece of fiction, story or novel, that youve ever read? Why?

Ligotti: The weirdest stories Ive ever read composed the collection Hollow Faces, Merciless

Moons (1977) by William Scott Home. The prose is so complex and recondite that its all but

unreadable, much like that of Clark Ashton Smith. Furthermore, Homes narratives are

baffling and sometime barely comprehensible, somewhat in the manner of Robert Aickman.

For a while I thought that Home was either an inexpert writer or a mental case. Then I found

an essay by him in a festschrift devoted to Lovecraft called HPL. The essay was lucid and

insightful. I forgot the title, but I included it in a compilation of criticism on Lovecraft when

I was working on a series of books called Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism for Gale

Research (now Gale Cenage). Its in volume 4 or 22.

Weirdfictionreview.com: Can you give us a list of five or so overlooked or

underappreciated weird writers, from any era, that readers should really take the time to

discover?

Thomas Ligotti: A Kayak Full of Ghosts: Eskimo Tales, ed. Lawrence Millman (I know that

the title of this book makes it seem an unlikely compilation of excellent weird stories, but it

is. I wrote a review of it for The New York Review of Science Fiction.)

Garden, Ashes by Danilo Ki (Ki called Bruno Schulz his god, so if you like the latter

author, you should investigate this unconventional novel by a major Serbian writer.)

The Fashionable Tiger by Jean Ferry in The Custom-House of Desire: A Half-Century of

Surrealist Stories, ed. J. H. Matthews (Ferrys story is an example of a crossover between

Surrealism and the uncanny. Most of the narrative is told in a matter-of-fact, rather banal

prose style that characterizes foreign works of the weird.)

The Colonels Photograph by Eugne Ionesco in The Colonels Photograph, and Other

Stories. (The Colonels Photograph told in a matter-of-fact, rather banal prose style is

linked in its bizarre, all but inscrutable events to Ionescos The Killer, a key play of the

Theater of the Absurd. Both works convey a feeling of what might be called dream terror,

that is, an inexplicable sense of a weird presence or set of circumstances. In his life, Ionesco

was an anguished individual who felt that human existence was nothing but alienation, fear,

and general misery.)

The Beelzebub Sonata by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkiewicz wrote philosophical

novels and plays. He is best-known for the latter, and any one of his plays consists of

a bizarre ensemble of characters who collectively express a nightmarish vision of the

demonic and the nihilistic.)

The Magicians Garden, and Other Stories (also published as Opium, and Other Stories) by

Gza Csth (Among his other accomplishments, Csth was a short story writer and

a psychiatrist. His stories often feature a similar mix of cruelly demented characters and

morbid atmosphere associated with the tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Csth was addicted to

morphine, opium, and sex. He committed suicide by taking poison not long after he shot and

killed his wife.)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

# Apr 2, 2013

Fiction

The Society Tiger

Jean Ferry

Jean Ferry (1906 1974) was primarily a screenwriter,

best known for his collaborations with Clouzot, Buuel, Louis Malle, and Georges Franju.

A satrap of the College of Pataphysics, he was known in his time as the greatest specialist in

the works of Prousts neighbor Raymond Roussel. His only book of fantastical tales, The

Engineer, was published in 1953 and recently brought back into print by ditions Finitude.

Andre Breton is said to have taken Ferrys wife Lila as the inspiration for his book LAmour

fou, and he called The Society Tiger, originally published in 1947, the most sensationally

new poetical text I have read in a long while. Thomas Ligotti, in his interview on WFR.com

lists The Society Tiger among his top under-appreciated weird stories. Readers in French

can find the story in a new edition of Ferrys fiction from Finitude, featuring 20 original

collages by Claude Ballar.

This story was originally reprinted here at WFR.com in November of 2011, in our first week

of operation, and the storys translator, Edward Gauvin, has recently updated and revised his

translation to this current form. The Editors

* * *

Of all the music hall acts as stupidly dangerous to public and performers alike, none fills me

with such supernatural horror as that old number known as the Society Tiger. For those

who havent seen it since the new generation knows nothing of the great music halls from

between the wars I shall recall this hoop-jumping spectacle. What I can neither explain nor

attempt to convey is the state of panicked terror and abject disgust into which this display

plunges me, as if into suspect and fearfully frigid water. I should simply avoid theatres where

this increasingly rare number still figures on the bill. Easier said than done. For reasons that

have always remained murky to me, the Society Tiger is never announced, I never expect

it, or rather, I do an obscure, barely expressed menace weighs on the pleasure I take from

the music hall. Though a sigh of relief may lighten my heart after the evenings final

attraction, I know but too well the fanfare and ritual announcing that number always

performed, I repeat, as if impromptu. As soon as the orchestra starts in on that brassy, ever-

so-typical waltz, I know what is about to happen; a crushing weight squeezes my chest, and

I feel the live wire of fear between my teeth like a sour, low-voltage current. I should go, but

I no longer dare. Besides, no one is moving, no one else shares my anxiety, and I know the

beast is already on its way. It also seems the arms of my seat are protecting me, but how

feebly

First, the theater is plunged into utter darkness. Then a spotlight comes up on the apron, and

the beam of that pathetic beacon comes to illumine an empty loge, usually quite close to my

seat. Quite close. From there, this pencil of light seeks out a door to the wings at the end of

the promenade gallery, and while the orchestras horns dramatically tackle into Invitation to

the Waltz, they enter.

The tamer is a heartrending redhead, a bit weary-looking. The only weapon she bears is

a black ostrich fan, whose plumes at first hide the lower half of her face; only her great green

eyes show over the dark fringe of undulating waves. A plunging neckline, bare arms

iridescent in the light as if in the mists of winter dusk, the tamer is sheathed tightly in

a romantic evening gown, a strange gown with a heavy sheen, black as the deepest depths.

The gown is cut from an incredibly supple and delicate fur. Atop it all, hair of flame spangled

with golden stars erupts in cascades. The whole thing is at once oppressive and slightly

comical. But who would think to laugh? The tamer, toying with her fan, reveals pure lips

frozen in a smile, and advances, followed by the spotlights beam, toward the empty loge

on the tigers arm, as it were.

The tiger walks in a fairly human fashion on its two hind legs; he is suited up as a dandy of

a refined elegance, and this suit is so perfectly tailored that its hard to make out, beneath the

gray flared slacks, the flowered waistcoat, the blindingly white jabot with its flawless ruffles,

and the frock coat fitted by a masters hand, the body of the animal beneath. But there is the

head, with its appalling rictus, the crazed eyes rolling in their crimson sockets, the furious

bristle of whiskers, and the fangs that sometimes glitter under curled lips. The tiger advances

quite stiffly, holding a light gray hat in the crook of his left arm. The tamer walks with

a measured step, and if sometimes she arches her lower back, if her bare arm tenses, showing

unexpected muscle under the tawny velvet of her skin, it is because she has just made

a violent, hidden effort to straighten her suitor, about to fall forward.

Here they are at the door to the loge, which the society tiger swats open before stepping aside

to let the lady through. And once she has taken her seat, even nonchalantly set an elbow on

the worn plush, the tiger drops himself into a chair beside her. At this point, the room usually

bursts into blissful applause. And I I watch the tiger, wanting to be somewhere else so

badly I could cry. The tamer gives a noble greeting with a nod of her controlled blaze. The

tiger goes to work, handling props laid out expressly in the loge. He pretends to study the

audience through an opera-glass; lifting the lid from a box of bonbons, he pretends to offer

some to his companion. He pulls out a silk handkerchief, which he pretends to sniff; he

pretends, to the great amusement of one and all, to consult the program. Then he acts the

gallant and, leaning toward the tamer, pretends to murmur some declaration in her ear. The

tamer pretends to take offense and, between the pale satin of her beautiful cheek and the

beasts stinking snout sown with saber blades, coquettishly raises the fragile screen of her

feather fan. At this, the tiger pretends to fall into despair, and wipes his eyes with the back of

a furred paw. And all throughout this lugubrious pantomime, my heart beats fit to tear inside

my ribcage, for I alone see, I alone know that this whole tasteless charade hangs by but

a miracle of willpower, as they say; that we are all in a state of horrifically precarious balance

the merest trifle could shatter. What would happen if, in the loge beside the tigers, that little

man with the look of a lowly office worker, that little man with pallid skin and tired eyes,

should for so much as a moment stop wanting? For he is the true tamer; the woman with her

red curls is but a figurehead. Everything depends on him; he is the one who makes a puppet

of the tiger, an automaton more tightly bound than by cables of steel.

But if that little man should suddenly start thinking about something else? If he died? No one

suspects the potential danger of every passing moment. And I who know, I imagine,

I imagine but no, better not to imagine what the lady in furs would look like if Better to

watch the end of the number, which always ravishes and reassures the public. The tamer asks

if someone in the audience would like to entrust her with a child. Who could refuse anyone so

charming? Theres always some unthinking woman wholl tender, toward that demonic loge,

a delighted baby, which the tiger cradles gently in the hollow of its folded paws, turning

a drunkards eyes on the little fleshly morsel. In a great thunder of applause, the theatre fills

with light, the baby is returned to its rightful owner, and the two partners take a bow before

exiting the way they came.

As soon as theyve passed through the door they never come back for an encore the

orchestra erupts into its most deafening fanfares. Shortly after, the little man wilts into his

seat, mopping his brow. And the orchestra plays louder and louder, to cover the roaring of the

tiger, itself again once past the bars of its cage. It howls like hell itself, rolls around shredding

its handsome clothes, which must be replaced at every show. Vociferations, tragic

imprecations of desperate rage, furious and devastating leaps against the sides of its cell. On

the other side of the bars, the false tamer hurriedly undresses so as not to miss the last metro.

The little man awaits her in the bistro by the station, the one called The Great Never.

However distant they sound, the hurricane of howls unleashed by the tiger tangled up in

ribbons of fabric might leave an unpleasant impression on the public. That is why the

orchestra plays the Fidelio Overture with all its might; thats why the stage manager, in the

wings, hurries the burlesque bicyclists onstage.

I hate the society tiger number, and I will never understand the pleasure the public takes in it.

(Original French publication in book form: Le Mcanicien, Gallimard, 1953; repr. Finitude,

2010)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Ligotti Interview in Subterranean MagazineDokumen8 halamanLigotti Interview in Subterranean Magazineewinig100% (1)

- Interview With Thomas Ligotti The Teeming Brain PDFDokumen14 halamanInterview With Thomas Ligotti The Teeming Brain PDFrelsinger100% (1)

- Wonder and Glory Forever: Awe-Inspiring Lovecraftian FictionDari EverandWonder and Glory Forever: Awe-Inspiring Lovecraftian FictionPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (1)

- Crypt Of Cosmic Carnage: The Very Best Weird Fiction 1917-1935Dari EverandCrypt Of Cosmic Carnage: The Very Best Weird Fiction 1917-1935Belum ada peringkat

- Elder Sign End Times Trilogy Book One: ArkhamDari EverandElder Sign End Times Trilogy Book One: ArkhamPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- A Century of Weird Fiction, 1832-1937: Disgust, Metaphysics and the Aesthetics of Cosmic HorrorDari EverandA Century of Weird Fiction, 1832-1937: Disgust, Metaphysics and the Aesthetics of Cosmic HorrorBelum ada peringkat

- That Ain't Right: Historical Accounts of the Miskatonic ValleyDari EverandThat Ain't Right: Historical Accounts of the Miskatonic ValleyBelum ada peringkat

- Autopsy of an Eldritch City: Ten Tales of Strange and Unproductive ThinkingDari EverandAutopsy of an Eldritch City: Ten Tales of Strange and Unproductive ThinkingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Cruise of Shadows: Haunted Stories of Land and SeaDari EverandCruise of Shadows: Haunted Stories of Land and SeaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Black Static #46 Horror Magazine (May - Jun 2015)Dari EverandBlack Static #46 Horror Magazine (May - Jun 2015)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Thomas Ligotti - The Spectral Link PDFDokumen51 halamanThomas Ligotti - The Spectral Link PDFDonatas Getneris100% (1)

- Harold Bloom in The Boston ReviewDokumen1 halamanHarold Bloom in The Boston ReviewRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- MEA CULPA - Eng. Trans PDFDokumen13 halamanMEA CULPA - Eng. Trans PDFRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Nightspore On Tormance (A Voyage To Arcturus)Dokumen499 halamanNightspore On Tormance (A Voyage To Arcturus)Ryan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Selected ProseDokumen265 halamanSelected ProseRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- The CINNAMON SHOPS Bruno Schulz Trans. by John Curran DavisDokumen27 halamanThe CINNAMON SHOPS Bruno Schulz Trans. by John Curran DavisRyan Rode100% (3)

- Moench Future History Chronicles VIDokumen18 halamanMoench Future History Chronicles VIRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- The Revelations of Glaaki (Sic)Dokumen91 halamanThe Revelations of Glaaki (Sic)Ryan Rode100% (1)

- The Insignificant & The CandleDokumen1 halamanThe Insignificant & The CandleRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- The COMET & OTHER STORIES Bruno Schulz Trans. by John Curran DavisDokumen12 halamanThe COMET & OTHER STORIES Bruno Schulz Trans. by John Curran DavisRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Fishing Knots, Swivels, SinkersDokumen41 halamanFishing Knots, Swivels, SinkersRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Michael DransfieldDokumen252 halamanMichael DransfieldRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Journey Across A Crater (JGBallard)Dokumen6 halamanJourney Across A Crater (JGBallard)Ryan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- David Allen Hulse The Cube of SpaceDokumen221 halamanDavid Allen Hulse The Cube of SpaceErich Webb100% (4)

- Thomas Ligotti - The Dark Beauty of Unheard-Of HorrorsDokumen9 halamanThomas Ligotti - The Dark Beauty of Unheard-Of Horrorsh335014100% (4)

- Thomas Ligottis The Last Feast of HarleqDokumen1 halamanThomas Ligottis The Last Feast of HarleqASK De OliveiraBelum ada peringkat

- Crypt of Cthulhu 68 1989.cryptic CosmicJukeboxDokumen69 halamanCrypt of Cthulhu 68 1989.cryptic CosmicJukeboxNushTheEternal100% (1)

- Crypt of Cthulhu 068 1989.cryptic CosmicJukeboxDokumen69 halamanCrypt of Cthulhu 068 1989.cryptic CosmicJukebox7777777100% (1)

- The Conspiracy Against The Human Race A Short Life of HorrorDokumen132 halamanThe Conspiracy Against The Human Race A Short Life of HorrorCarlos Maglione100% (3)

- Thomas Ligotti Interviewed (2011) + Jean Ferry TaleDokumen9 halamanThomas Ligotti Interviewed (2011) + Jean Ferry TaleRyan RodeBelum ada peringkat

- Songs of A Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe by Thomas Ligotti: October 2016Dokumen6 halamanSongs of A Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe by Thomas Ligotti: October 2016Slania SsBelum ada peringkat

- More Than Simple Plagiarism: Ligotti, Pizzolatto, and True Detective's Terrestrial HorrorDokumen12 halamanMore Than Simple Plagiarism: Ligotti, Pizzolatto, and True Detective's Terrestrial HorrorAnderson Faleiro100% (1)

- 00-Price - Mystagogue Gnostic Quest Secret BookDokumen4 halaman00-Price - Mystagogue Gnostic Quest Secret BookBert SomsomBelum ada peringkat