Neighborhood Planning 2 PDF

Diunggah oleh

Veronica TapiaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Neighborhood Planning 2 PDF

Diunggah oleh

Veronica TapiaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of Planning Education and Research

http://jpe.sagepub.com

Neighborhood Planning

W. Dennis Keating and Norman Krumholz

Journal of Planning Education and Research 2000; 20; 111

DOI: 10.1177/073945600128992546

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jpe.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/20/1/111

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning

Additional services and information for Journal of Planning Education and Research can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jpe.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jpe.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://jpe.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/20/1/111

Downloaded from http://jpe.sagepub.com at SUNY AT BUFFALO on January 4, 2009

Keating & Krumholz

Commentary

Commentary

Neighborhood Planning

W. Dennis Keating & Norman Krumholz

he neighborhood planning idea has roots that go back over one hundred years.

The neighborhood was seen by settlement house social workers such as Jane

Addams, Robert Woods, Mary Simkhovitch, and others as the means not only to rebuild

the congested neighborhoods of the immigrant poor but also to reconstruct the entire

city. Most settlement workers pressed for housing reforms and improvements limited to

poor neighborhoods, but early planners James Ford (1916) and Benjamin C. Marsh

(1909) suggested variations of Ebenezer Howards Garden City as a means of decentralizing the working class, reducing congestion, and improving the neighborhood, city,

and region. During the early 1900s, planners proposed neighborhood civic centers

consisting of grouped public and private institutions that would encourage neighborhood pride and betterment. Such a scheme was suggested as part of a general effort at

city beautification in the 1907 St. Louis plan (Davis 1908). A darker side of neighborhood planning also emerged as Richmond, St. Louis, Chicago, Atlanta, and other cities

experimented with neighborhood planning and zoning for racial exclusion (Silver

1985).

The tendency of city planners to translate general aspirations into concrete community designs is clearly evident in Clarence Perrys contribution to neighborhood planning. Perrys Neighborhood Unit Plan was an attempt to adapt the social uniformity

sought by the settlement house workers into a blueprint for the automobile age (Perry

1924). His scheme included a residential space for a given number of families, recreation space, local schools, commercial shops, and the separation of vehicular and

pedestrian traffic. By the late 1940s, Perrys neighborhood unit had become one of the

most widely discussed urban planning ideas (Stein 1945; Dahir 1947).

In the 1960s, neighborhood advocate Jane Jacobs (1961) stated her contention that

diverse and multiuse neighborhoods were key to city vitality. Her views favoring

high-density and unplanned development challenged Perrys ideas of fixed and

restricted community scale. Sociologist/planner Herbert Gans, whose research (1962)

found a vibrant social network behind decaying physical facades of neighborhoods

threatened by urban renewal, also attacked the physical determinism of the neighborhood plan. Paul Davidoff (1965) offered a new planning approach that would assist

threatened neighborhoods to advocate their own interest in a challenge to the official

Abstract

Neighborhood planning in American cities goes back more than one hundred

years. The settlement house social workers

pressed demands for neighborhood and

housing improvements. They were followed by early city planners, who included

neighborhood multipurpose civic centers

within their comprehensive citywide

plans. Clarence Perrys neighborhood

unit plan of the 1920s saw the urban neighborhood as a means to organize space and

socialize residents. Today, with the rise of

community development corporations,

neighborhoods are again the focus of renewed interest. This commentary discusses the past and present of neighborhood planning within the context of a survey of ACSP faculty who are teaching

neighborhood planning.

Norman Krumholz is a professor in the

Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. Previously he was a

planning practitioner in several cities,

including Cleveland, where he served as

planning director. He is now president of

the American Institute of Certified Planners (1999-2001).

W. Dennis Keating is presently Interim

Dean of the Levin College of Urban Affairs

at Cleveland State University. He was the

founding director of its Master of Urban

Planning, Design and Development Program. He and Krumholtz have coauthored

and coedited Revitalizing Urban Neighborhoods (1996) and Rebuilding Urban Neighborhoods (1999).

Journal of Planning Education and Research 20:111-114

2000 Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning

111

Downloaded from http://jpe.sagepub.com at SUNY AT BUFFALO on January 4, 2009

112

Keating & Krumholz

city plan. Together, the critiques by Jacobs, Gans, Davidoff, and

others helped to end the urban renewal clearance program

and laid the groundwork for the citizen and neighborhood

involvement requirements written into the federal Community

Development Block Grant Program of 1974. Citizen participation is now a routine element in American urban planning.

At the start of the new millennium, neighborhood groups

in many American cities are involved in commenting on or

shaping the planning, zoning, and development proposals

that affect their neighborhoods. Numerous cities have official

planning staffs that continually seek neighborhood input,

modifying their citywide plans to reflect constituency preferences. Most important, powerful new interest in urban neighborhoods has been spurred by the accomplishments of some

2,500 community development corporations (CDCs) in localities all over America. Through 1996, these CDCs have built

some 500,000 units of affordable housing produced nationwide (Orlebeke 1997). In addition, they have been responsible

for the construction of large amounts of commercial and

industrial space in difficult locations. The CDCs are popular

with both liberal and conservative politicians and with funding

intermediaries. They have been institutionalized in federal

legislation. They are an important new dynamic in urban areas

and an important source of jobs for planning students.

Because of growing interest in neighborhood planning as a

career path, it is timely to look at how the subject of neighborhood planning is being addressed by ACSP member schools.

Given the interest of government in collaborating with universities on community development, neighborhood planning

can be an important connection. One example is the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Developments University-Community Partnership Center (COPC) program.

involved in teaching NCP. Most survey respondents were full or

associate professors; all but two were full-time faculty.

The survey responses made clear that there was a wide

range of courses offered, including planning, architecture,

community development, and housing and neighborhood

revitalization. Many were designated as studios and workshops.

Forty-six were graduate courses; only nine were undergraduate. A majority of the courses were required and most were

offered for just one term. Student enrollment varied from

eight to twenty-five. Based on the responses to the questions on

teaching techniques and the strengths and weakness of each,

we compiled the data shown in Table 1.

In discussing the dynamics of teaching NCP, particularly

when it involves field research and often real clients, respondents noted many problems and issues:

neighborhood organizations may have weak leadership,

making collaboration difficult;

with fieldwork, there is often a conflict between the deadlines of a real client versus the academic calendar;

communication between students and real-world clients

and their constituents can often prove difficult, leading to

frustration and delay;

setting priorities for neighborhoods can prove difficult

when the needs are many, especially in distressed neighborhoods, and the resources are limited; and

the logistics of transporting students off campus to a neighborhood site can often present problems of funding, liability, and assimilation.

On the positive side, respondents noted that

students often have a heightened interest in an NCP class

because of the attraction of working with real clients;

when students work in groups, intensive interaction may result;

the experience may result in job opportunities for students;

and

Survey

despite problems, as one respondent noted, When stu-

In 1997, the American Planning Association (APA) asked

us to survey the faculty of ACSP member schools to determine

the current state of the art in teaching neighborhood collaborative planning (NCP). In commissioning this first survey of its

kind, APA hoped to reinforce this planning specialty. We

mailed our survey instrument to 283 ACSP faculty selected for

areas of specialization related to NCP and received 43

responses. Of the eighty schools in the United States represented in the Tenth ACSP Guide to Graduate Education in Urban

and Regional Planning, we received positive responses from at

least one faculty member at about half (thirty-five) of the

schools. This is a small but representative sample of faculty

dents and clients click, its magic.

All of our respondents believe NCP could be very important in the planning curriculum. The following are recurrent

reasons given to support this view: NCP exposes students to

community partnerships and a more diverse population while

providing assistance to community clients, it provides insights

into the dynamics of low-income neighborhoods, it helps fulfill

the service mission of urban universities, and it educates the

students about issues related to social justice and equity.

We offer two examples to support our argument of the

importance of teaching NCP in the curriculum. One of the

best-known and most successful examples of NCP is the East St.

Downloaded from http://jpe.sagepub.com at SUNY AT BUFFALO on January 4, 2009

Commentary

Louis Action Research Project

(ESLARP). Its chair, Professor Kenneth Reardon (1998) of the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign

(UIUC), has previously described

ESLARP and assessed its effectiveness

as empowerment planning. He points

out the benefits and pitfalls of NCP. In

an October 1999 update on ESLARPs

accomplishments, Reardon estimated that 4,000 UIUC students have

volunteered in East St. Louis since

1987, 1,800 of whom have earned academic credit for their field-based

learning. One hundred graduate

research assistants have been funded

and eighty masters theses and

research papers related to ESLARP

have been written. ESLARPs impact

on both UIUC faculty and students

and the East St. Louis neighborhoods

in which they have worked is indeed

impressive. Not only has ESLARP

involved many colleges and departments at UIUC, but it has helped satisfy the universitys commitment to

urban service. In recognition of his

work and its importance in disadvantaged communities, Professor Reardon in 2000 was awarded the Presidents Award of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

Here at the Levin College of

Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University, a graduate class titled Neighborhood Planning has long been

offered, focusing each year on a selected Cleveland area neighborhood.

Students work with community- based

clients on projects. This and other

programs and classes at the college

have led many graduates to continue

to work in the field of neighborhood

redevelopment and planning, both

with local governments and CDCs.

Alumni of the Neighborhood Planning course are now heading several

Cleveland CDCs and working for

113

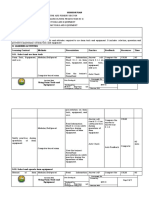

Table 1.

Neighborhood Collaborative Planning Survey:

Question 10, teaching techniques.

Technique

Strength

Weakness

Team teaching Diversity of perspectives applied

partner keeps focus, use skills

of other faculty

Can confuse students

Neighborhood Experimental knowledge historic

history

precedence

Fascinates students

Shows what planners have done

No theory to place the action within

Sometimes too idiosyncratic

Often not available

Time-consuming in quarter system

Neighborhood Experimental knowledge

analysis

Abstract vision

Apply research techniques

Data-driven reports

Objective

Basic planning skills applied

No theory to place the action within

Dehumanizes

Inadequate data availability

Time-consuming in quarter system

Data sources not always accurate

Mapping

Experimental knowledge

Abstract vision

Learn neighborhood

Helps to see land use patterns

No theory to place the action within

Scale problems

Fosters elitism

Readings

Multiple perspectives

Provide case studies

Information rapidly communicated

Breadth and depth of issues

Can review at own pace

Too abstract for some

Some studies are dated

May not be done

Abstract

Films/videos/

slides

Very realistic documentation

Dramatic visual

Engaging

Piques student interest

Some are dated

Can seem like entertainment

Superficiality

Role-play

Experience different roles

Reluctance to participate

Neighborhood Experimental knowledge

tours

Essential for familiarzation

Local knowledge

See complexity of real world

Realistic exposure

No theory to place the action within

Logistics

Hard to match with readings

Real clients

Increased interest for students

Practical/political

Students feel professional

Strong dose of realism

Essential; grounds project

Client may suffer

Introduces complication

Students may become cheap labor

Unpredictability

Field research

Students awareness and

understanding improve

Students learn where to get

information

Essential to understand

neighborhood

Networking skills

Time-consuming; logistics

Learn what works and what doesnt

Hard to find appropriate hearings

Observation

Downloaded from http://jpe.sagepub.com at SUNY AT BUFFALO on January 4, 2009

Time-consuming

114

Keating & Krumholz

Clevelands planning and community development departments. Many Cleveland CDCs are associated with the Cleveland Housing Network (CHN), a nationally recognized network of eighteen CDCs providing affordable housing

(Krumholz 1997). These are but two examples of why NCP

should be supported within the planning academy.

planning practitioners. Such a survey could reveal how students in NCP classes found their jobs working for CDCs,

whether they felt their NCP courses had prepared them adequately for neighborhood assignments and what other teaching approaches and materials might have been more effective.

In the alternative, ACSP and APA conference panels and

roundtables can help to advance our knowledge.

Conclusion

Authors Note: Complete copies of the Teaching Neighborhood Collaborative

Planning Survey are available from the authors or via APAs Web page:

http://www.planning.org.

The authors share the prevailing view of our respondents

that ACSP member schools should reinforce or elevate the

teaching of NCP to a more important position in their curriculum. There is no doubt that CDCs and other neighborhood-based organizations are having a significant impact on

urban neighborhoods. They have become a major supplier of

affordable housing in the United States as well as being important commercial developers and providers of social services.

Their numbers and their competence continue to grow, and

more and more planners working at the neighborhood level,

inside local government and through nonprofit agencies, are

helping them. The many problems of disinvested urban neighborhoods have confounded traditional formulas; CDCs have

succeeded in at least making progress on some of these problems. In the process, they have learned to survive on the rocky

soil of the poorest of urban neighborhoods, making a contribution along the way to the greater society. ACSP member

schools should do more to support faculty to prepare their students through neighborhood planning to contribute to this

and similar efforts.

This effort should be supported by further research. The

APA NCP survey did not include any student evaluations. As a

result, we have no data independent of the faculty responses to

measure the effectiveness of the teaching of NCP courses.

Such information is essential, possibly from a survey aimed at

students in NCP courses. We also did not survey students who

took NCP courses and then later became neighborhood

References

Dahir, J. 1947. The neighborhood unit plan. New York: Russell Sage.

Davidoff, Paul. 1965. Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal

of the American Institute of Planning 34(4).

Davis, D. F. 1908. The neighborhood centerA moral and educational factor. Charities and the Commons 19(2):1504-6.

Ford, James. 1916. Residential decentralization. In City planning,

edited by J. Nolan. New York: Appleton.

Gans, Herbert. 1962. The urban villagers. New York: Free Press.

Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The death and life of great American cities. New

York: Random House.

Krumholz, Norman. 1997. The provision of affordable housing in

Cleveland: Patterns of organizational and financial support. In

Affordable housing and urban redevelopment in the United States,

edited by Willem Van Vliet. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Marsh, Benjamin C. 1909. An introduction to city planning: Democracys challenge to the American city. New York: Marsh.

Orlebeke, Charles J. 1997. New life at ground zero. Washington, DC:

Urban Institute.

Perry, C. 1924. A plan for New York and its environs Vol. 7. New York:

New York Regional Planning Association.

Reardon, Kenneth M. 1998. Enhancing the capacity of community-based organizations in East St. Louis. Journal of Planning

Education and Research 17:323-33.

Silver, Christopher. 1985. Neighborhood planning in historical

perspective. Journal of the American Planning Association 51 (2):

161-74.

Stein, Clarence, S. 1945. The city of the futureThe city of neighborhoods. American City 60 (11): 123-24.

Downloaded from http://jpe.sagepub.com at SUNY AT BUFFALO on January 4, 2009

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Beijing Brief ContrerasDokumen4 halamanBeijing Brief ContrerasVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Neighbourhood ParadigmDokumen21 halamanNeighbourhood ParadigmVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Harvey Comunidad y Nuevo UrbanismoDokumen3 halamanHarvey Comunidad y Nuevo UrbanismoVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Syllabus Ethnography of Space and PlaceDokumen12 halamanSyllabus Ethnography of Space and PlaceVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Journal of Planning History 2009 Lloyd Lawhon 111 32Dokumen23 halamanJournal of Planning History 2009 Lloyd Lawhon 111 32Veronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- How Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationDokumen19 halamanHow Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Poverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodDokumen48 halamanPoverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Defining NeighborhoodsDokumen16 halamanDefining NeighborhoodsVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Origin of The Neighbourhood UnitDokumen20 halamanOrigin of The Neighbourhood UnitVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Women, Neighbourhoods and Everyday LifeDokumen15 halamanWomen, Neighbourhoods and Everyday LifeVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- 2009 Galster - What Is NeighbourhoodDokumen21 halaman2009 Galster - What Is NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaBelum ada peringkat

- Community Development Through Sport.Dokumen16 halamanCommunity Development Through Sport.Veronica Tapia100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Lo2. Using Farm Tools and EquipmentDokumen8 halamanLo2. Using Farm Tools and Equipmentrobelyn veranoBelum ada peringkat

- What Is A Spiral Curriculum?: R.M. Harden & N. StamperDokumen3 halamanWhat Is A Spiral Curriculum?: R.M. Harden & N. StamperShaheed Dental2Belum ada peringkat

- Child Development in UAEDokumen6 halamanChild Development in UAEkelvin fabichichiBelum ada peringkat

- PIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewDokumen54 halamanPIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewMaria Francisca SarinoBelum ada peringkat

- Louisa May Alcott Little Women Websters Thesaurus Edition 2006Dokumen658 halamanLouisa May Alcott Little Women Websters Thesaurus Edition 2006Alexander León Vega80% (5)

- Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya: FeaturesDokumen8 halamanVidura, Uddhava and Maitreya: FeaturesNityam Bhagavata-sevayaBelum ada peringkat

- A Proposed Program To Prevent Violence Against Women (Vaw) in Selected Barangays of Batangas CityDokumen16 halamanA Proposed Program To Prevent Violence Against Women (Vaw) in Selected Barangays of Batangas CityMarimarjnhioBelum ada peringkat

- Genre AnalysisDokumen6 halamanGenre Analysisapi-273164465Belum ada peringkat

- Organisational Behaviour PDFDokumen129 halamanOrganisational Behaviour PDFHemant GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Thinking and Working Scientifically in Early Years: Assignment 1, EDUC 9127Dokumen10 halamanThinking and Working Scientifically in Early Years: Assignment 1, EDUC 9127MANDEEP KAURBelum ada peringkat

- Group Reporting RubricsDokumen1 halamanGroup Reporting RubricsDonald Bose Mandac90% (68)

- Didactic Unit Simple Present Tense ReviewDokumen3 halamanDidactic Unit Simple Present Tense ReviewEmersdavidBelum ada peringkat

- (Latest Edited) Full Note Sta404 - 01042022Dokumen108 halaman(Latest Edited) Full Note Sta404 - 01042022Tiara SBelum ada peringkat

- Davison 2012Dokumen14 halamanDavison 2012Angie Marcela Marulanda MenesesBelum ada peringkat

- NBC September 2023 Poll For Release 92423Dokumen24 halamanNBC September 2023 Poll For Release 92423Veronica SilveriBelum ada peringkat

- WendyDokumen5 halamanWendyNiranjan NotaniBelum ada peringkat

- Karachi, From The Prism of Urban Design: February 2021Dokumen14 halamanKarachi, From The Prism of Urban Design: February 2021SAMRAH IQBALBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 9 English Q2 Ws 3 4Dokumen9 halamanGrade 9 English Q2 Ws 3 4Jeremias MalbasBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence Law Reading ListDokumen9 halamanEvidence Law Reading ListaronyuBelum ada peringkat

- Vasquez, Jay Lord U.: PRK 3, Brgy. Guinacutan, Vinzons, Camarines Norte Mobile No.:09076971555Dokumen4 halamanVasquez, Jay Lord U.: PRK 3, Brgy. Guinacutan, Vinzons, Camarines Norte Mobile No.:09076971555choloBelum ada peringkat

- Department of Labor: Errd SWDokumen151 halamanDepartment of Labor: Errd SWUSA_DepartmentOfLaborBelum ada peringkat

- Peace Corps Dominican Republic Welcome Book - December 2011CCD Updated June 13, 2013 DOWB517Dokumen50 halamanPeace Corps Dominican Republic Welcome Book - December 2011CCD Updated June 13, 2013 DOWB517Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsBelum ada peringkat

- Cengage LearningDokumen12 halamanCengage LearningerikomarBelum ada peringkat

- Information Brochure of Workshop On Nanoscale Technology Compatibility Mode 1Dokumen2 halamanInformation Brochure of Workshop On Nanoscale Technology Compatibility Mode 1aditi7257Belum ada peringkat

- Ps Mar2016 ItmDokumen1 halamanPs Mar2016 ItmJessie LimBelum ada peringkat

- Curriculum and Materials CbliDokumen9 halamanCurriculum and Materials CbliNAZIRA SANTIAGO ESCAMILLABelum ada peringkat

- Cmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203Dokumen1 halamanCmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203 Cmd. 00427992039203Younas BalochBelum ada peringkat

- Final Notes of Unit 5 & 6 & 7Dokumen49 halamanFinal Notes of Unit 5 & 6 & 7shubhamBelum ada peringkat

- Department of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsDokumen2 halamanDepartment of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsJohn Gerte PanotesBelum ada peringkat

- Holiday Homework Ahlcon International SchoolDokumen8 halamanHoliday Homework Ahlcon International Schoolafetmeeoq100% (1)