Gazi Erdem - Diyanet ... Şeyhulislamlık

Diunggah oleh

mhabibsaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Gazi Erdem - Diyanet ... Şeyhulislamlık

Diunggah oleh

mhabibsaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

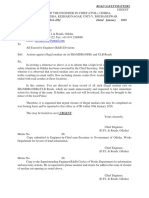

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

ORIGINAL

ARTICLES

Blackwell

Oxford,

The

MUWO

1478-1913

0027-4909

XXX

2008

Muslim

Hartford

UK

Publishing

World

Seminary

Ltd

The

R

eligious

Muslim

Services

World in

VTolume

urkey98

: From

April

the 2008

Office ofS

Religious Services in

Turkey: From the Office of

eyhlislam to the Diyanet

to the D

Gazi Erdem

Attach for Religious Affairs

Turkish Consulate General

New York, New York

he Republic of Turkey occupies a unique place in balancing religion,

democracy and secularism among Islamic countries. Turkey is the only

Islamic country that has included secularism in its constitution and

devotedly practices it. The balance between Islam, secularism and democracy

in Turkey is praised by many modern governments of the world, including the

United States.1 This peculiarity became possible because of Turkeys cultural

and religious heritage.

The mixture of both Islamic and Western traditions played an important

role in the construction of the political and cultural identity of modern Turkey.2

For centuries, Turkeys relationship with the Western and Muslim worlds and

its geographical proximity to the East and the West made it possible to

understand the values of both sides. In this respect, many scholars have

considered Turkey as a bridge between the two worlds.

In addition, from the earliest period of Turkish history, a moderate

perception of religion can be observed clearly among various Turkish societies.

Religious freedom has always been guaranteed for all groups, even before

Turks embraced Islam. Turkish people coexisted with those of other religions

throughout the pre-Islamic period of their history. Although not a prevailing

fact, some Turks, apart from Shamanism, embraced different religions such as

Buddhism, Judaism and Christianity. This helped them to understand pluralism

and practice tolerance towards those of other religions in their societies.3

The modern Turkish state traces its origin to the legacy left by the Ottoman

Empire. One legacy is the policy of the state towards religion. One should look

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden,

MA 02148 USA.

199

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

closely at the Ottoman Empire in order to evaluate the Turkish states

perception of religion and religious organizations. In this article, I will evaluate

the Ottoman policy of religion seen in the Millet System (System of Nation),

Islamic religious services in the Ottoman Empire, which were conducted

through the office of eyhlislam, the transition of the system from the

Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey, and lastly, the Presidency of

Religious Affairs (PRA), the legal basis of the Turkish states perception of

religion and its position as a governmental agency.

The Millet System, its Implementation and the

Ottoman Experience

The Ottoman Empire was composed of an extraordinary mixture of people

expanding into three continents: Asia, Europe and Africa. Apart from small

minorities or groups, the main ethnicities within the Ottoman territory included

Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Bulgarians, Albanians, Romanians, Serbs, Croats,

Hungarians, Armenians, Kurds, Moors and Jews.4 The term millet originally,

without taking ethnicity into consideration, meant a religious community.

The term acquired its contemporary meaning only in the nineteenth century5

by the Western-trained, Western-oriented, secular ruling elite in the final

centuries of the Ottoman period.6

There were three main religions in the Ottoman Empire: Islam, Christianity

and Judaism. Islam was the religion of the ruling class and the dynasty. The

state was ruled according to Islamic law and did not admit any distinction

between religion and politics.7 There were a large number of diverse

economic, social, religious and political groups, which all had very little in

common. The Ottomans had to find and enforce a suitable system to rule over

these various groups. This system would be the millet system.8

The millet system began as a political organization that granted

non-Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Empire the right to organize into

communities possessing certain delegated political powers under their own

ecclesiastical chiefs.9 In this system, the head of the millet, the patriarch or the

rabbi, was directly responsible to the state for the administration of all of his

subjects.10 In this manner the Ottomans could utilize the services of the natural

leadership of their subject communities throughout their reign. Thus, the

religious hierarchy of the subject communities became an important

instrument of Ottoman political administration.11 According to the Ottoman

archives, some sultans appointed Christian clergy even before the conquest of

Istanbul. For example, Sultan Yildirim Bayezid, after the conquest of the city

of Antalya, assigned a metropolitan and paid him a regular income from the

Ottoman treasury in the form of timar.12 This indicates that from the very

beginning the rulers of the Empire understood and accepted religious services

200

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

as a kind of public matter. Therefore it was understood that religious services

should be organized by the government and maintained under the control of

the state.

On the other side, as indicated above, the Ottoman legal system was based

on the shariah and the Islamic legal code. Islamic affairs in the Empire were

run by the eyhlislam on behalf of the state and the sultan (the head of

state). The eyhlislam had both political and religious authority, as the

Ottoman state provided the means and independence for the eyhlislam to

organize and administer Islamic affairs.13

During the Tanzimat period in 186263, the Greek Orthodox and the

Armenian Christians respectively obtained their regulations, which can be seen

as the constitutions of the Ottoman Christians. Through these regulations,

the Ottoman government introduced secular laws for the churches.

This experience gradually expanded the implementation of secularism to

other government offices and legislation. Secular education followed. In

many areas of legislation, secular laws were adopted from Western laws.

These modernizing reforms influenced the relationship between the state and

religion and changed the appearance of the Islamic character of the state

structure, the legal system, the educational establishments and the political

culture in the Ottoman Empire.

It should not, however, be thought that the Ottoman Empire completely

changed its legal system with the introduction of secular laws. In reality, the

fundamentals of Islamic law were protected and implemented until the end of

the Empire, at the very least, on the level of appearance. As an important part

of the modernization and Westernization process, the Ottomans introduced

secular laws into many spheres. This secularization began before the

establishment of the secular Turkish Republic.

The Office of Seyhlislam

The title of Shaykh al-Islam came into use at the time of the Buyids

(Buwaihids). The title acquired an increasingly specific function during the

Ottoman Empire and finally became the Office of Mufti of Istanbul.14 Shaykh

al-Islam was used as a title of honor for religious dignitaries and scholars

beginning from the second half of the tenth century until the end of the

Ottoman Empire throughout Islamic history.15 In the Ottoman Empire, during

the time of the Mehmet II, it became the most important position among the

ulema (religious scholars/learned corps). The eyhlislam was accepted as the

leader of all muderrises, muftis, kadis and kadiaskers (professors, religious

administrators, judges and chief judges, respectively). The post was the highest

rank of religious affairs. The eyhlislam would petition the grand vizier for

the appointment of these dignitaries.16

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

201

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

The influence of ulema was restored again under Suleyman the

Magnificent by the official recognition of the Mufti of Istanbul as head of the

learned corporation, adopting the title of eyhlislam.17 At the beginning of the

19th century the office of eyhlislam combined the administration of justice,

religious counseling and educational services under its jurisdiction. All the

kadis, muftis and muderrises of the madrasahs were under the authority of the

eyhlislam. This means that the functions and duties of the Ministry of Justice,

Ministry of Education, the General Directorate of Foundations and the

Presidency of Religious Affairs (PRA) of modern Turkey were carried out

and implemented by the office of eyhlislam.18

From the time of Suleyman onward, the eyhlislam was ranked

virtually equal with the grand vizier, the Sadrazam. Both were the only

officials to receive their investiture at the sultans own hands. At the

ceremonies the two advanced together so that neither should take lead of the

other. When either paid a ceremonial visit to the other he was received with

equal and peculiar honors. The grand viziers had greater power, but the

eyhlislams enjoyed greater esteem. The influence of eyhlislam was such

that only when he and the vizier could work in harmony was either secure in

their office, otherwise their mutual intrigues soon led to the fall of one or the

other. The grand vizier was bound to keep in constant touch with the

eyhlislam on state affairs.

The eyhlislam was so busy with political business that he was obliged

to maintain a special assistant called Telhisci to act as his intermediary with the

Porte, and required a secretary general to control his chancery. His household

was managed by a kahya, who also administered the foundations. The private

applications for fetwas that were addressed to him were dealt within a special

department of his office, called the fetwa-hane, which was controlled by a

commissioner known as the Fetwa Emini. All these offices were filled by

exceptional ulema.19

The privileges and power of the eyhlislam increased directly with the

increased importance of the office. The sultans treated the eyhlislam and the

Grand Vizier equally. When the eyhlislam came into his presence, the sultan

would meet him by standing up. When a sultan sat on the throne for the first

time, in other words, during the special ceremony of the enthroning of a

sultan, the eyhlislam would hand the sultans sword to him. On the 26th

night of every Ramadan, which is regarded by Muslims as the Night of Power

(Kadir Gecesi ), the grand vizier would come to the eyhlislams mansion to

break the fast with him. These kinds of traditions show the place of

eyhlislam in the state protocol.20

Despite the fact that the eyhlislams were very powerful, we should not

think of them as independent of the state. Starting from the eyhlislam, all

202

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

members of the ilmiyye organization were employed by the state in order to

work in the sphere of education, justice, administration and religious affairs.

Thus it could be said that the office of eyhlislam was dependent on and

responsible to the political administration in the state mechanism. This means

that the office of eyhlislam was not an independent office such as the

church organization in the West at that time. The government could investigate

all activities of the office. Rulers appointed the eyhlislam and other members

of his office and, when it was required, they dismissed them of their duty.21

As we have indicated above, the Ottoman state was a form of Islamic

theocracy and did not admit any distinction between religion and politics.

Islam was the religion of the ruling class and the dynasty.22 Thus the sultan was

the leader of the country both in the sphere of religion and government. The

eyhlislam could be described as the person who helped both the sultan and

the vizier control the state, the law and the operations of administration from

the scope of religion or in accordance with religion.23 In other words, it could

be suggested that the main function of the eyhlislam was to legitimize the

political authority, the sultanate and its acts, the policy of the state and its

decisions from the perspective of the Islamic religion.

The eyhlislams separated religious and worldly affairs in a clear and

distinct manner. They secured the balance between these two fields. When

they were asked something about political arrangements, regulations or laws

which were conducted by the administration they would say that This is not

a religious affair or this is not an affair of regulated by Shariah thus one

should behave how he was ordered.24

The eyhlislam, as the head of the ulema, petitioned the grand vizier for

the appointment, promotion and dismissal of the madrasa staff. This duty was

fulfilled by the grand viziers until the last decades of 16th century.25 From then

on, the eyhlislam acquired the authority to propose the nomination and

dismissal of the kadis of important regions, thus effectively controlling the

entire organization of the ulema. In the same way as the grand vizier was the

absolute representative of the sultans executive authority, the eyhlislam

became absolute representative of the sultans religious authority.26

The ulema represented the greatest power within the state independent of

the grand vizier. The kadiaskers of Anatolia and Rumelia were the government

functionaries responsible for the administration of religious law, possessing

the power to appoint and dismiss kadis and religious dignitaries. They gave

the final decision in lawsuits within the scope of shariah. The head of the

ulema, the eyhlislam, was not considered a member of the government.

Nevertheless, he came in time to exercise great influence in the affairs of the

state. It should be noted that the grand vizier petitioned the sultan for the

appointment of a new eyhlislam, though the sultan was not obligated to

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

203

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

accept the nomination.27 It was fitting for the grand vizier to place the

eyhlislam above himself, out of respect.28

Another important duty of the eyhlislam in the Ottoman Empire was that

they were the sultans counselors. Before making important decisions, the

sultan would summon the grand vizier or the eyhlislam to the palace for

advice.29 According to the Ottoman rule of imperial council, (Divan-

Hmayun) the eyhlislam was not one of the original members of this

council, though he took part in extraordinary meetings. From the 18th century

onward, consulting the eyhlislam on governmental matters became a

tradition and the eyhlislam became one of the members of the imperial

council.30 From this angle, it could be said that the eyhlislam had no political

authority in the Empire.31 This is certainly true as far as the classical age of the

Ottoman Empire was concerned.

Looking from another angle, however, we can see the greatest power of

the eyhlislam. It is known that during Ottoman rule, some bodies of the

Ottoman army such as Janissaries and Sipahis, made some protests against

their rulers. Sometimes these uprisings threatened the sultans throne. For

example, in 1588, the Sipahis were paid in debased coin whose value had

fallen by half. The Sipahis then obtained a fetva from the eyhlislam, proving

this to be an injustice, and thus went on to the palace to demand the death of

Mehmed Pasha, the author of the reform. At its the end, the sultan ordered the

execution of Pasha.32 It seems safe to say the power of fetwa at that time could

not be underestimated. Holding this power in hand made the eyhlislams

powerful and important men not only among the public but also among

governmental bodies.

Usually, during times of financial and economic distress and other such

disturbances, the populace of Istanbul was ready to riot. Public opinion would

support these uprisings and a fetwa of the eyhlislam would give legal

expression to this popular sanction. Typical of this were the uprisings which

led to the deposition of Sultan Ibrahim in 1648, Mehmet IV in 1687, Mustafa II

in 1703, Ahmed III in 1730 and Selim III in 1807.33

It seems that the office of eyhlislam was, in a sense, superior to that of

the sultan himself since the eyhlislam could issue a fetwa declaring a sultans

deposition to be required by the exigencies of the shariah. No war might be

declared, or policies such as the slaughter of the sultans male relatives,

declared without the eyhlislams official sanction. But the sultans supremacy

was in practice usually assured by his ability to dismiss a eyhlislam who

opposed his wishes and appoint a more amenable successor. It was only in

the 17th and 18th centuries, when the sultans had lost their absolute control

of governmental affairs, that the eyhlislams were sometimes able to

command sufficient support in the ruling institution or among the inhabitants

204

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

of the capital to oppose sultans with success, and even then they very often

suffered for doing so.34

Ottoman society experienced total transformation and many reforms in the

th

19 century. During this time, the effects and functions of religion were

retrograded and weakened in the social, political and administrative structures

of the state. At this time, civil and military bureaucrats took over the

administrative bodies.35 Consequently, the office of eyhlislam was pushed

backward in terms of quality and quantity and gradually digressed from the

duty of controlling the administration with the scope of religion.36

There were several arrangements that affected the authority of the office

of eyhlislam in the administration of justice, religious counseling and

educational services. The abolishment of the Yenieri corps, the establishment

of new assemblies, the foundation of ministries, the importation of some

un-Islamic laws from Western countries, the establishment of the Nizamiye

courts in addition to the Shariah courts, the establishment of new schools to

educate civil and military bureaucrats independent of madrasahs, and the

establishment of the Ministry of Foundations can be shown as examples of

this.37 Through these restrictions the power of the eyhlislam was lessened

on the one hand, and on the other hand the process of secularism was initiated

by taking away the effect of religion on affairs of the state.38

Until the abolishment of the Yeniceri corps in 1826, the eyhlislams used

their residences as their offices. The headquarters of the Yenieris, which was

called Agakaps, was then assigned for the eyhlislam to be used as his

office. The office was transformed to a public office. Again, during these same

years, the eyhlislam was accepted as one of the members of the

governmental cabinet as the Minister of Shariah (eriye Nazr). His term for

the office became dependent on the term of his own government.39

By transfering some duties of the eyhlislamm to some newly established

councils after the Noble Edict of the Rose Garden (Glhane Hatt-

Hmayunu Tanzimat Ferman) such as the Supreme Council for Judicial

Regulations (Meclis-i Vala-i Ahkam- Adliye),, and after the Reform Edict of

1856 (Islahat Ferman), the Supreme Council of the Reforms (Meclis-i Ali-i

Tanzimat), and Supreme Council for Judicial Regulations, the effect of

eyhlislam on state affairs was gradually lessened.40 The new government of

the Ottoman Empire in 1916 made the Ministry of Justice responsible for all of

the courts, and the Ministry of Education for all of the madrasahs, schools and

other educational institutions.41 The most important functions of the eyhlislam

were occupied by other institutions during this course of time. The only

function of the eyhlislam which was left to his personal attention was that

of religious affairs. In other words, the office of eyhlislam was made into an

office whose only duty was to maintain the religious services of the state.

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

205

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

The office of eyhlislam served Ottoman society for 498 years without

any interruption from its beginning until its abolishment. During this period,

130 eyhlislams had come to power. In the early years of the Ottoman Empire

the eyhlislams were appointed to the post for life, but in the later centuries

the dismissal of the eyhlislams became an ordinary regulation. When the

sultan saw that the eyhlislam was causing hardship and difficulty in state

affairs, he immediately dismissed him. The history of the institution shows that

80 out of 130 eyhlislams were dismissed by sultans and some others were

forced to resign from duty. It gives us a clue to understand why the last 12

eyhlislams left the post through resignation.42

The Ministry of Religious Affairs and Foundations

Many people suppose that all of the Ottoman institutions collapsed and

disappeared immediately after the establishment of the new Turkish Republic,

but in fact Ottoman social institutions were transferred to new generations and

became the essence of the culture. Thus it seems safe to say that the religious

institutions, which were formed during the Ottoman Empire, continued on

during the Republic period, though some of the duties and functions were

different. The Ministry of Religious Affairs and Foundations (eriye ve Avkaf

Vezareti ) was founded among the ministries of the first government of the

Turkish Grand National Assembly on May 3rd, 1920. The duties of the Ottoman

eyhlislam and the Ministry of Foundations were combined into this new

ministry. Religious affairs were executed under this organization for four years

until the founding of the Presidency of Religious Affairs (PRA) on March 3rd,

1924.43 The passage of the authorities and the responsibilities of the office of

the eyhlislam can be observed here clearly. The first president of the Turkish

Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatrk, assigned the mufti of Karacabey, Mustafa

Fehmi Efendi, as the first minister. The Ministry of Religious Affairs and

Foundations was ranked in the order of protocol as the first ministry after the

prime minister among the members of the cabinet.44

The functions and authorities of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and

Foundations were discussed at the end giving fetwa; legal decision and the

administration of the shariah courts and the institution of education were

determined as the fundamental duties of the Ministry.45 Despite the fact that

during the last decades of the Ottoman Empire the only official duty left for

the eyhlislam was the administration of religious affairs, most probably due

to extraordinary conditions which were experienced by the country in those

days, all of the pre-Tanzimat period duties of the office of eyhlislam were

determined fit for this ministry. In order to be able to respond to the religious

problems of the society, according to the conditions of the age, a council of

fetwa was created in the modern ministry. Another council was created for the

206

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

publications of Islamic books. An additional council was created for the

administration of madarahs and religious education.46

In the next pages of this article, the role of the Ministry of Religious Affairs

and Foundations as a bridge between the Ottoman Office of eyhlislam and

the PRA of the Republic of Turkey will be explored.

The Establishment of Modern Turkey and the PRA

Modern Turkey was established from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire and

inherited the Ottoman legacy, which, especially during the last period of her

long life, introduced secular laws in the field of legislation, administration, and

education. The founders of the Republic of Turkey were well educated people

of the Empire and had wide knowledge of modern states, the position of the

Empire, and the public. They did not disregard Ottoman experiences, and thus

adopted these reforms and accelerated them for the sake of forming a modern

Turkish society.

This age was the age of nation states. Most of the empires had collapsed.

The old monarch-state would not be successful in forming a new society.

The Ottoman experience of the last century showed that reality. Though many

Ottoman governments tried to improve state organizations and institutions,

and attempted to develop society and industry, they were not successful.

The founders of modern Turkey shaped the new state and its institutions

on the basis of a secular model inspired by the West and by the ideals of

modernism and secularism.

After the formation of the Republic of Turkey, the new Turkish

government carried on reform efforts from the point where the old Ottoman

government stopped. The caliphate was abolished as the first step of

secularization on March 3rd, 1924. On that same day, the state also abolished

the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Foundations on the grounds that religion

and religious services should be kept out of politics. It was replaced with the

PRA, an institution attached to the Office of the Prime Minister which received

its allowance from the budget of the premiership in accordance with law 429.47

Law 429 clarified that the duty of legislation and execution of the law

belonged to the National Assembly and the government, respectively.

The Diyanet became authorized to decide matters concerning the beliefs,

worship and ethics of Islam, to administer the worshipping locations, and

to appoint and dismiss religious officials. The intervention of religion and

religious officials of the administration toward the state was prevented.

Ultimately, the law assigned religious functionaries to be under the control

of the state as public employees. This was the concept of unannounced

secularism in Turkey at that time. With this law, religion and the administration

of the state were clearly separated from each other.

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

207

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

As previously indicated, in the Ottoman Empire the state was responsible

for religious affairs and the eyhlislam ran the religious affairs on behalf of

the state. After the formation of the Republic, the PRA was founded as an

important public department and was responsible for the administration of

religious affairs in the areas of Islamic faith, practices and moral principles.

Clearly, the responsibility and authority of the state during the Ottoman Empire

were passed on to the modern Republic of Turkey in a different way.

In modern Turkey, the state also claims responsibility for the organization and

administration of religious affairs via the Diyanet, the PRA.48

The establishment of modern Turkey opened a new era in the history of

the Turkish nation. Secularism is one of the basic pillars of the Republic

of Turkey. This principle is prescribed in the Constitution of 1982. Article 2 of

this constitution describes the Republic of Turkey as a secular state.49 It was

also so prescribed in the preceding constitutions. Secularism became a

constitutional principle on February 5, 1937 but, as explained above, the

principle of secularism had existed de facto since the foundation of

the Republic.

According to Article 136 of the constitution, the Department of Religious

Affairs, which is within the general administration, shall exercise its duties

prescribed in its particular law, in accordance with the principles of secularism,

removed from all political views and ideas, and aimed at national solidarity

and integrity.50 According to the first article of Law 633, the duties of the PRA

are as follows: to execute the works concerning the beliefs, worship and

ethics of Islam, enlighten the public about their religion, and administer the

sacred worshipping places.51

The central organization of the PRA was established in 1924, and consisted

of the Committee of Consultation and central officers. In 1927, the Department

of Investigating the Quranic Pages, the Directorate of Religious Institutions,

the Directorate of Officials and Records and the Directorate of Documents and

Papers were added to the central organization. The Law about the Presidency

of Religious Affairs, its Establishment and Obligations, numbered as 2800, was

accepted on the 14th of June, 1935, and put into effect on June 22nd, 1935; this

was the first organizational law of the PRA. With this law, the structure of the

organization, its formation of personnel, the qualities of central and provincial

officers and their appointment principles were determined. The PRA, however,

was reorganized in accordance with new conditions that had arisen because

of Law 5634; this was put into effect on April 20th, 1950. According to this law,

some names of the units in the organization were changed, an office of vicepresidency was added to the present organization and two new directorates

were established, such as the personnel of religious institutions and the

directorate of publications. Furthermore, for the first time a Mobile Preaching

208

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

unit was founded and all preachers were transferred to salaried status.

The PRA was reorganized by the 1961 Constitution, with Law 633 dated

June 22nd, 1965, and named as the Law about the Presidency of Religious

Affairs, its Establishment and Obligations. This law also started a new phase

for the PRA in its historical development and made its central organization

adopt todays organic structure.52

The organization of the Diyanet with its present functional structure is

composed of the central, provincial and abroad organizations.53 The central

organization has three main units:

1.

2.

Main Service Units:

a) The Higher Board of Religious Affairs: The Higher Board is an advisory

committee to the PRA. Its elected 16 members are made up of

distinguished religious scholars. Its main duty is to research

religious issues which are debated among the people and share their

outcome with them, and give full answers to the questions of

people in relation to religious issues in a complete, scientific,

and open manner.

b) The Board for the Investigation of Copies of the Quran: The duty of this

organization is to examine the copies of the Quran that are to be

published in written and audio-visual form by the PRA and other

organizations, and to endorse them when they are accurate.

c) The Department of Religious Services: This department serves to

enlighten and educate Turkish society about religion. It determines the

correct times of prayer, sacred days and nights and the beginnings of the

lunar months. It cooperates with related establishments and institutions

concerning this subject matter.

d) The Department of Religious Education: This office prepares and applies

a yearly in-service education plan in order to develop and increase the

professional formation of the staff. It also carries out affairs related to the

opening, education and administration of the courses of the Quran and

of education centers.

e) The Department of the Pilgrimage: This office is charged with every kind

of service and planning, inside Turkey and abroad, related to the travels

of pilgrims who want to perform their pilgrimage and lesser pilgrimages

(Umrah). It cooperates with related establishments and governmental

agencies on this matter.

f ) The Department of Religious Publications: This office enlightens society

about religion by publishing audio-visual works, books and periodicals.

It is also charged with the library services of the PRA.

g) The Department of External Relations: This office offers religious services

to Turkish citizens abroad. It arranges educational courses and seminars

for personnel who will be sent to work abroad. It also offers guidance

about the services offered by the PRA, to committees and groups who

come from outside of Turkey.

Consultation and Control Units:

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

209

The Muslim World

3.

Volume 98

April/July 2008

a) The Department of Inspecting Committee

b) The Office of Legal Advisor

c) The Department of Development of Strategy

Units of Assistance:

a) The Department of Personnel

b) The Department of Administrative and Fiscal Affairs

c) Directorate of the Circulating Capital Management

d) Directorate of Protocol

e) Directorate of Media and Public Relations.

The provincial organization of the PRA consists of the mufti offices in

every province and district, and the directorates of education centers in some

cities. The external establishment of the PRA is organized in the countries

where Turkish citizens live as the Councilors of Religious Services connected

to the Turkish Embassies, and as the Attachs of Religious Services connected

to the Consulates General.

The president of the Diyanet is appointed by the approval of the president

of the Republic of Turkey upon the suggestion of the Cabinet. The muftis of

cities (provinces) in the provincial organization are appointed by the approval

of the president of the Republic of Turkey upon the suggestion of both the

state minister, whose duty is to supervise both the Diyanet and the prime

minister. The vice presidents and the heads of the departments in the central

organization are appointed on the approval of the prime minister or the state

minister whose duty it is to supervise the Diyanet upon the suggestion of

the president of Diyanet. The councilors and the attachs in the external

organization are appointed by the approval of the president of the Republic of

Turkey upon written decree, which is signed by the state minister whose duty

it is to supervise the Diyanet, the minister of foreign affairs and the prime

minister. The other members of the central organization and muftis of districts,

preachers, teachers of learning centers, instructors of the Quran, local

inspectors, etc. are appointed by the president of Diyanet. The muftis of

provinces appoint the imams. There are several requirements, conditions and

restrictions for every functionary that must be met by each candidate, such as

degree of education, age, gender and the like.

The Diyanet tries to teach the principles of Islam, such as unity,

cooperation and helping one another among the Turkish people according to

the principles specified in the constitution of the Republic of Turkey. It does

this by striving toward national solidarity, unity, and by remaining above all

kinds of political views and thoughts. The Diyanet, accepting differences as

part of the richness of the country, warns society against negative activities of

various destructive, harmful and sectarian movements and enlightens the

nation about dangerous, harmful and unethical behavior and habits, which

weaken them materially and spiritually and lead to social instability.

210

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

The Diyanet tries to understand and evaluate the traditions, expectations and

sensitivities of society. It provides religious services decorated and illuminated

by knowledge and good conduct, benefiting from todays technological

developments and communicational facilities and historical experiences. The

Diyanet strives to have religious officers with high levels of education and

culture who will lead society, who will understand the people they address

and find religious solutions to their problems, and who will live an exemplary

life and implement good through their deeds and words.54

Some scholars see the Diyanet as a contradiction to the secular state.

However, most do not because Turkey upholds these following principles:

1)

2)

3)

4)

Religion should not be dominant or effective agents in state affairs.

The provision of unrestricted freedom for the religious lives of individuals and

religious liberties are under constitutional protection.

The prevention of the misuse and exploitation of religion is essential for the

protection of the public interest.

The state has the authority to ensure the provision of religious rights and

freedoms as the protector of public order and rights.55

According to the current PRA, Prof. Dr. Ali Bardakoglu, since it is part

of the state machinery and bureaucratic system, the Diyanet is a public

institution. Its public character pertains to the fact that it provides an

organizational structure and policy, while rendering religious services. Its

public character also pertains to establish a balance between demands and

freedoms. The Diyanet is also an independent (public) institution because it

enjoys freedom in scholarly activities, intellectual discussions of Islamic issues,

in the production of religious knowledge and its dissemination to the public.

There is no intervention in the interpretation of religion by any organization.

The Diyanet is also a civil institution because it was founded in response to

the peoples religious needs. The Muslim population of the country needs to

learn about their religion freely in light of authentic scholarship. The Diyanet

was established to meet such needs in society; it therefore has a democratic

and civil basis.56 It could be proposed that the Turkish understanding of

secularism can be seen clearly in these explanations.

Conclusion

The modern Turkish states perception of religion can be traced back to

the Ottoman Empire. Modern Turkey was established on the ruins of the

Ottoman Empire and inherited the Ottoman state legacy. The founders of

modern Turkey shaped the new state as a national and secular republic. By

assuming the Ottoman policy on religion, they accepted religious services as

one of the responsibilities of the state. They did not leave religious services to

the congregations despite the fact that they knew this way has been observed

in the West for centuries.

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

211

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

When the Republic of Turkey was founded, the caliphate was abolished

as the first step toward secularization. The same day, the state also abolished

the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Foundations, which was created to take

over the duties of the office of eyhlislam. The PRA was established and

made responsible for the administration of religious affairs in the areas of

Islamic faith, practices and moral principles as an important public department.

The Diyanet is not exactly a continuation of the Ottoman office of eyhlislam

in terms of all of its functions and duties but is a continuation in the point

of religious services and a continuation of the office of eyhlislam in the

post-Tanzimat shape and functions. Hence, the PRA is not an innovation

of the founders of the Republic of Turkey.

Today 99% of Turkish people are Muslim. Islam is one of the major identity

references and an effective social reality in Turkey. Islamic values remained

deeply rooted in Turkish society. Depending on the rituals, between 25 80%

of Turkish people practice the prescribed rituals such as daily prayers, Friday

prayers and fasting during Ramadan.57 Turkish families by and large embrace

Islamic moral values. Even those who are not attentive in their religious

practices demand that their children should be trained in accordance with

Islamic moral values. An overwhelming majority of Turkish families send their

children to summer religious courses organized by the Diyanet in the mosques.

Most Turkish people advocate that religious services and religious education

should be performed by a state organization, namely by the Diyanet.

The institution produces sufficient services and makes progress in its

duties with more than 85,000 employees in 77,800 mosques in Turkey and

abroad. In exchange, the nation accepts the services of the Diyanet with

pleasure.

The modern structure of the Diyanet and the method of appointment of

its high level administrators starting from the PRA, implies that the institution

has been governed by political authority. Insiders and most Turkish people

know that politicians try not to intervene in the religious affairs of the country.

This is not only because of their esteem of religion and religious administrators

but also due to their fear of public pressure and losing votes. Many

experiences have shown that the public does not forgive those politicians who

interfere in religious matters. During the last five years especially, State Minister

Mehmet Aydin, who is responsible for the Diyanet and is a very well known

professor of Islamic studies, declared that the Diyanet is governed from the

PRA by its functionaries. As far as it is known, he did not let any outsiders

intervene with respect to the jobs and appointments the Diyanet makes.

The Diyanet should be an autonomous institution in its structure and should

only, though the results of special elections, approve of the president and

other high level functionaries that come into office.

212

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

Turkey has been very successful in combining Islamic culture, democracy

and secularism. The Diyanet plays an important role in the publics adoption

of these values and in balancing society in accordance with these values. With

these characteristics, Turkey is a unique example of how a Muslim nation

can support democracy based on secularism and the implementation of

democratic norms. In this connection, the Diyanet is also a good example for

conducting religious services in accordance with Islamic values and the

principles of secularism.

Endnotes

1.

http://usinfo.state.gov/dhr/Archive/2006/Jan/25566311.html

2.

Kucukcan, Talip, State, Islam, and Religious Liberty in Modern Turkey:

Reconfiguration of Religion in the Public Sphere, Brigham Young University Law Review,

2003, at: http://lawreview.byu.edu/archives/2003/2/KUC.pdf.

3.

Algl, Hseyin, 3slam Tarihi, (3stanbul, 1986), Vol. 4, 446447.

4.

Ortayl, 3lber, Osmanl 3mparatorlugunda Millet, in: Tanzimattan Cumhuriyete

Trkiye Ansiklopedisi, (3stanbul, 1986), Vol. 4, 997; Davison, R. H., Essays in Ottoman and

Turkish History, 17741923: The Impact of the West, (University of Texas Press, Texas, 1990), 11.

5.

For more discussion about the term millet see: Braude, B., Foundation Myths of

the Millet System, in Braude, B. and Lewis, B. eds: Christians and Jews in the Ottoman

Empire: the Functioning of a Plural Society, Vol. 1, (Holmes and Meier, New York and

London, 1982), 6974.

6.

Karpat, K. H., Ottoman Views and Policies Towards the Orthodox Christian

Church, Greek Orthodox Theological Review, Vol. 31, No: 12, 139.

7.

Ware, T., Eustratios Argenti: A Study of the Greek Church under Turkish Rule,

(Clarendon Press, Texas, 1964), 2.

8.

Shaw, S. J., The Aims and Achievements of Ottoman Rule in the Balkans, Slavic

Review, Vol. 21, No: 4, 1962, 617. See also: Karpat, Kemal H., Millets and Nationality:

The Roots of the Incongruity of Nation and State in the Post-Ottoman Era, Christians and

Jews in the Ottoman Empire: the Functioning of a Plural Society, (Ed. Braude, B., - Lewis,

B.), Vol. 1, 148149; Kk, Cevdet, Osmanllarda Millet Sistemi ve Tanzimat, in:

Tanzimattan Cumhuriyete Trkiye Ansiklopedisi, (3stanbul, 1986) Vol. 4, 1009.

9.

Eryilmaz, B., Osmanli Devletinde Gayrimuslim Tebanin Yonetimi,

(Risale Yayinlari, Istanbul, 1990), 17. See also: Cahnman, W. J., Religion and Nationality,

The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 49, 1944, 525.

10. Braude, B., Community and Conflict in the Economy of the Ottoman Balkans,

1500 1650, (PhD. Thesis, Harward University, Cambridge, Mass., 1977), 93.

11. Frazee, C. A., The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece 18211852,

(Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1969), 1.

12. Inalcik, H: Hicri 835 Tarihli Suret-i Defter-i Sancak-i Arnavid, (Turk Tarih

Kurumu Yayinevi, Ankara, 1954) Nos: 100, 122, 148, 162, 186, 200, 270, 299.

13. Bardakoglu, Ali, Religion and Society New Perspectives from Turkey, (Publication

of the Presidency of Religious Affairs, Ankara, 2006), 22.

14. Glasse, Cyril, Shaykh al-Islam, The New Encyclopeadia of Islam, (Rownan &

Littlefield Publishers, New York, 2002), 421.

15. Ta, Kemaleddin, Trk Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, (3z Yaynclk, 3stanbul, 2002), 67.

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

213

The Muslim World

Volume 98

April/July 2008

16. Uzunarl, Ismail Hakk, Osmanl Tarihi, (Trk Tarih Kurumu Yaynevi, Ankara,

1982) V. 3, 449.

17. Gibb, H. A. R. and Bowen, Harold, Islamic Society and the West, (Oxford

University Ppress, London, 1957) V. 1, Part II, 84.

18. Ta, Trk Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 77.

19. Gibb, H. A. R. and Bowen, Harold, Islamic Society and the West, 86.

20. Boyacoglu, Ramazan, Hilafetten Diyanet 3leri Bakanlgna Gei, (Unpublished

Ph.D Thesis, Ankara 1992), 47.

21. Kaya, Kamil, Trkiyede Din-Devlet 3likileri ve Diyanet 3leri Bakanlg,

(Unpublished PhD. Thesis, Istanbul, 1994), 81; Ta, Trk Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 7273.

22. Ware, T., Eustratios Argenti: A Study of the Greek Church under Turkish Rule, 2.

23. Okumu, Ejder, Trkiyenin Laikleme Serveninde Tanzimat, (3nsan Yaynlar,

3stanbul, 1999), 164.

24. Aksoy, Mehmet, eyhlislamlktan Bugne: eyhlislamlktan Diyanet 3leri

Bakanlgna Gei, (nel Yaynevi Kln, 1998), 12; Kaya, Trkiyede Din-Devlet 3likileri ve

Diyanet 3leri Bakanlg, 82.

25. Ta, Trk Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 77.

26. Inalcik, Halil, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300 1600, (Orpheus

Publishing Inc. New Rochelle, NY, 1993), 9697; Newby, Gordon D., Shaykh al-Islam,

A Concise Encyclopeadia of Islam, (Oneworld, Oxford, 2004), 194.

27. Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300 1600, 96.

28. Repp, R. C., Shaykh al-Islam, Encyclopeadia of Islam, (New Edition,

Brill, Leiden, 1995) V. 9, 401.

29. For some relevant examples see Inalcik The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age

1300 1600, 93.

30. Ortayl, 3lber, Trkiye 3dare Tarihi, (TODAIE Yaynlar, Ankara, 1979), 149;

Ta Trk Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 7071.

31. Repp, R. C., Shaykh al-Islam, 400; Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical

Age 1300 1600, 94.

32. Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300 1600, 92.

33. Ibid., 98.

34. Gibb, H. A. R. and Bowen, Harold, Islamic Society and the West, 8586.

35. Dursun, Davut, Osmani Devletinde Siyaset ve Din, (Iaret yaynlar, 3stanbul,

1992), 315316.

36. Mardin, Serif, Yeni Osmanl Dncesinin Doguu, (3letiim Yaynlar, 3stanbul,

1996), 158161.

37. Dursun, Davut, Din Brorasisi, (3aret Yaynlar, 3stanbul, 1992), 174.

38. Okumu, Ejder, Trkiyenin Laikleme Serveninde Tanzimat, (3nsan Yaynlar,

3stanbul, 1999), 293.

39. Boyacoglu, Ramazan, Hilafetten Diyanet 3leri Bakanlgna Gei, 51; Tas, Trk

Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 80.

40. Erdem, Gazi, Osmanli Impatorlugunda Hiristiyanlarin Soayal ve Dini Hayatlari

(18561876), (Unpunblished PhD. Thesis, Ankara, 2005), 8586.

41. Kaya, Trkiyede Din-Devlet 3likileri ve Diyanet 3leri Bakanlg, 87; Tas, Trk

Halknn Gzyle Diyanet, 82.

42. Yavuzer, Hasan, Dini Otorite ve Tekilatlarn Sosyolojik Analizi (Diyanet 3leri

Bakanlg rnegi), (Unpublished PhD. Thesis, Kayseri, 2005), 4960.

43. Kahraman, Hakan, Sosyolojik Adan Diyanet 3leri Bakanlg zerine Bir

3nceleme, (Unpublished MA Thesis, Istanbul, 1993) 28; Bulut, Mehmet, eriye Vekaletinin

Dini Yayn Hizmetleri, Diyanet Ilmi Dergi, Vol. 30, No:1, 34.

214

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

Religious Services in Turkey: From the Office of EYHLISL5M to the DIYANET

44. Ii, Ismail, Kuruluundan Gnmze Diyanet Ileri Bakanlg, (Diyanet Ileri

Bakanlg Yayinlari, Ankara, 1999), 1213.

45. Bulut, Mehmet, Birinci Meclis Dnemi Din Hizmetleri, Diyanet Aylk Dergi,

Nisan, 1993, No: 28, 30.

46. Ibid., 30.

47. Sarikoyuncu, Ali, Milli Mucadelede Din Adamlari II, p. 5/14, at:

http://www.diyanet.gov.tr/turkish/default.asp

48. Bardakoglu, Ali, Religion and Society: New Perspectives from Turkey, 23.

49. http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/english/constitution.htm

50. Ibid.

51. Mevzuat/Kanunlar/633 Sayl Diyanet 3leri Bakanlg Kurulu Ve Grevleri

Hakknda Kanun, at: http://www.diyanet.gov.tr/turkish/default.asp

52. http://www.diyanet.gov.tr/english/default.asp

53. See for the organizational structure: http://www.diyanet.gov.tr/english/default.asp

54. http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/english/constitution.htm

55. Bardakoglu, Ali, Religion and Society New Perspectives from Turkey, 2425.

56. Ibid., 2427.

57. http://www.stargazete.com/index.asp?haberID=79197

2008 The Author. Journal Compilation 2008 Hartford Seminary.

215

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Ahmet Insel - The Akp and Normalizing Democracy in TurkeyDokumen16 halamanAhmet Insel - The Akp and Normalizing Democracy in TurkeymhabibsaBelum ada peringkat

- Andrew Hess - The Moriscos PDFDokumen25 halamanAndrew Hess - The Moriscos PDFmhabibsaBelum ada peringkat

- Deringil - AbdulhamitDokumen15 halamanDeringil - AbdulhamitHayati YaşarBelum ada peringkat

- Religion, Politics and The Politics of Religion in TurkeyDokumen32 halamanReligion, Politics and The Politics of Religion in TurkeyLiberales InstitutBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- BOOK REVIEW Nationalism and Social Reform in India Vijay Nambiar Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform by Charles H HeimsathDokumen9 halamanBOOK REVIEW Nationalism and Social Reform in India Vijay Nambiar Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform by Charles H HeimsathNehaBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Policy, Planning and Programming (1) Lecture TwoDokumen30 halamanEconomic Policy, Planning and Programming (1) Lecture Twokelvinyessa906100% (1)

- E VerifyDokumen1 halamanE VerifyGerencia De ProyectosBelum ada peringkat

- Updates On Jurisprudence (SPL)Dokumen33 halamanUpdates On Jurisprudence (SPL)cathy1808Belum ada peringkat

- Strategy For Socialist RevolutionDokumen10 halamanStrategy For Socialist RevolutionGnaneswar PiduguBelum ada peringkat

- Median CutDokumen1 halamanMedian CutAkshay Kumar SahooBelum ada peringkat

- Class 8 PPT1 India After IndependenceDokumen15 halamanClass 8 PPT1 India After IndependencePulkit SabharwalBelum ada peringkat

- Pith and SubstanceDokumen14 halamanPith and SubstanceAmar AlamBelum ada peringkat

- MigrationDokumen1 halamanMigrationburychurchBelum ada peringkat

- General Assembly: United NationsDokumen15 halamanGeneral Assembly: United NationsSachumquBelum ada peringkat

- People v. BayotasDokumen1 halamanPeople v. BayotasRyw100% (1)

- An Interface Between Sixth Schedule and Tribal AutonomyDokumen19 halamanAn Interface Between Sixth Schedule and Tribal AutonomyExtreme TronersBelum ada peringkat

- IRR of R.A 9255Dokumen7 halamanIRR of R.A 9255Tata Bentor100% (1)

- Reaction Paper - Legal Clinic (Navotas, Laoag City)Dokumen3 halamanReaction Paper - Legal Clinic (Navotas, Laoag City)Bianca Taylan PastorBelum ada peringkat

- Mark Kramer, New Evidence On Soviet Decision-Making and The 1956 Polish and Hungarian CrisesDokumen56 halamanMark Kramer, New Evidence On Soviet Decision-Making and The 1956 Polish and Hungarian CrisesEugenio D'Alessio100% (2)

- 18 Concerned Trial Lawyers of Manila v. VeneracionDokumen1 halaman18 Concerned Trial Lawyers of Manila v. Veneracionkafoteon mediaBelum ada peringkat

- English ProjectDokumen18 halamanEnglish ProjectRudra PatelBelum ada peringkat

- Essential Question: - What Caused World War I?Dokumen13 halamanEssential Question: - What Caused World War I?naeem100% (1)

- People Vs AustriaDokumen2 halamanPeople Vs AustriaKier Arque100% (1)

- Opposition To Defendants' Motion For Order To Compel The Production of Documents From PlaintiffDokumen17 halamanOpposition To Defendants' Motion For Order To Compel The Production of Documents From PlaintifflegalmattersBelum ada peringkat

- Community Tax Certificate PRINTDokumen2 halamanCommunity Tax Certificate PRINTClarenz0% (1)

- Farinas v. Executive SecretaryDokumen3 halamanFarinas v. Executive SecretaryPamelaBelum ada peringkat

- B-I - Political ScienceDokumen14 halamanB-I - Political ScienceANAND R. SALVEBelum ada peringkat

- 2.2 - Conference of Maritime Manning Agencies, Inc. v. POEA PDFDokumen11 halaman2.2 - Conference of Maritime Manning Agencies, Inc. v. POEA PDFFlorence RoseteBelum ada peringkat

- Shelley, Louise. "Blood Money." Foreign Affairs. 21 Feb. 2018. Web. 21 Feb. 2018)Dokumen3 halamanShelley, Louise. "Blood Money." Foreign Affairs. 21 Feb. 2018. Web. 21 Feb. 2018)chrisBelum ada peringkat

- IB History Beginning of Cold WarDokumen6 halamanIB History Beginning of Cold Warsprtsfrk4evr100% (1)

- 500.social Science Bullets PDFDokumen522 halaman500.social Science Bullets PDFMarimarjnhio67% (3)

- Role of Judiciary: Decisions States ResourcesDokumen5 halamanRole of Judiciary: Decisions States Resourcestayyaba redaBelum ada peringkat

- ReceptionDokumen1 halamanReceptionSunlight FoundationBelum ada peringkat

- Digest People v. MonerDokumen5 halamanDigest People v. Monerclarisse75% (4)