Effects of AntiPyretics

Diunggah oleh

2 FunkyHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Effects of AntiPyretics

Diunggah oleh

2 FunkyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

VOLUME 34-MAY 1997

Personal Practice

Antipyretic Therapy

K. Rajeshwari

Fever is among the most common manifestations of disease and antipyresis is one

of the most usual therapeutic intervention

undertaken. A variety of microbial products including endotoxins and exotoxins

are recognized as exogenous pyrogens

which induce host cells to produce mediators known as endogenous pyrogens. The

best studied endogenous pyrogen is interleukin 1, others include tumor necrosis factor and interferons(l). Most known endogenous pyrogens act on the anterior hypothalamus to elicit local generation of prostaglandins. Fever represents the response

of the host to a neurologic signal demanding thermal upregulation. Studies have

shown temperature elevation to enhance

several parameters of immune function like

T cell activation, mononuclear production

of leukocyte migration inhibition factor,

neutrophil function and macrophage oxidative metabolism(2,3) while high temperatures prove deleterious by altering natural

killer cell activity, generation of cytotoxic T

lymphocytes and alteration in neutrophil

morphology and function(4). While the

clinical situation is much too complex to allow definite conclusions, the preponderance of evidence suggests that temperatures in the range of usual fever may renFrom the Department of Pediatrics, Hindu Rao

Hospital, Delhi 110 007.

Reprint requests: Dr. K. Rajeshwari, Department of

Pediatrics, Hindu Rao Hospital, Delhi 110 007.

der many host defenses *noro active andmany pathogens more susceptible to there

defenses more active and many pathogens

more susceptible to these defenses. Thus

the limited data that exist do support the

hypothesis that fever has some beneficial

effects in human infection. This communication addresses the need and available

modalities for antipyresis in pediatric practice.

Is Antipyresis Required?

A common stated reason for aggressive

antipyretic therapy is the prevention of febrile seizures or other central nervous system effects. Although the height of fever is

considered important in seizure induction^), it is not clear whether aggressive

antipyresis alters the risk of an initial febrile seizure. Epilepsy may manifest during febrile episodes. Fever may precipitate

status epilepticus in some children and further result in motor incoordination and

other disabilities(6). Most physicians can

recall instances of transient delirium in febrile patients but it is difficult to determine

whether the reversible manifestation arises

from the fever or from the disease producing the fever(7). It is yet not scientifically

proved whether antipyretic therapy can

prevent or reverse delirium in identifiable

high risk situations or minimize risk of status epilepticus.

Another common reason for antipyretic

therapy is symptomatic treatment of fever.

It is less clear exactly what symptoms are

being treated and to what extent

antipyresis actually makes the patient feel

better. Conversely, there is a possibility

that a febrile patient given antipyretics may

become abruptly afebrile or even hypother407

PERSONAL PRACTICE

mic with profuse diaphoresis and greater

discomfort than if untreated(8). In treating

fever symptomatically one should not lose

sight of the fact that elevated temperature

whatever their physiologic function do

serve as a signal both to the patient and to

the caregiver. Non specific suppression of

fever may deprive one of clues to a need

for further diagnostic investigation or for

changes in therapy.

In the light of available scientific data,

the decision for antipyresis is usually based

on the "perceived" risk and benefits, both

of the fever itself and of the available treatments. The definition of dangerous hyperpyrexia requiring treatment is clearcut and

supported by clinical data. A rectal temperature above 41.4C is definitely harmful

and requires therapy(9). In other patients, a

cited reason for trying to suppress fever is

concern about hypoxic injury to tissues, especially the cardiovascular system. Metabolic rate and tissue oxygen demand increase with elevated body temperature.

Cardiac compromise has been reported at

extreme hyperthermic temperatures. Similarly, subclinical compromise of cardiac

function has been documented during febrile illnesses. Thus patients with severe

valvular heart disease with precarious coronary perfusion may benefit from prompt

antipyresis to prevent worsening of clinical

condition.

In addition to the antipyretic effect,

most commonly used antipyretics particularly Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory

Drugs (NSAIDS), have considerable analgesic effect which promotes a general feeling of well being for the duration of effect.

In the usual clinical setting, antipyresis is

generally resorted to for promotion of this

feeling of "well being" as well as for reduction of fever, often to allay anxiety and reassure the patient and relatives. In this context, the effect (beneficial or otherwise) of

408

antipyretics on the biological process is as

yet not clear.

Physical Antipyresis

Physical modalities such as sponging,

ice packs or cooling blankets are most often

used in conjunction with pharmacological

antipyresis. It has been shown that use of

iced water or alcohol in water is superior to

sponging with tepid water though associated with more patient discomfort(lO). External cooling by sponging in a bath tub with

5-10 cm of tepid water increases evaporation and promotes heat loss. Cold water

should be avoided because it results in peripheral vasoconstriction and shivering,

causes greater discomfort to the child and

may also increase the core body temperature(10,11). Sponging for 20 minutes was

found to be ineffective(12) and sponging

for 2-4 hours has been recommended(13).

Wet compresses covering the lower legs or

trunk are frequently used to lower the

body temperature. Usually they are

changed after 10-15 minutes and repeated

till the skin feels cool. No controlled trials

proving their efficacy are available.

There is a fundamental illogic to the use

of external application of cold to lower

body temperature in a patient with true

fever. Because of the altered hypothalamic

set point, the patient is already responding

as if to a cold environment. Physical methods should only be used after administration of antipyretic drugs, so that the hypothalamic set point is lowered from its febrile values. Even in this setting, their utility in the reduction of fever can be debated.

One study found that sponging febrile children with tepid water after antipyretic

therapy had no more effect on defervescence than antipyretics alone(12). Thus

physical methods may be used only if there

is failure of pharmacotherapy or when temperature is to be lowered for a reason not

associated with true fever (heat stroke, or

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

induction of profound hypothermia in

head trauma or cardiac surgery)(13)

Pharmacological Antipyresis

Antipyresis occurs with differsnt classes of substance including steroids, acetylsalicylic acid, dipyrone, acetaminophen

and the non steroidal anti-inflammatory

agents represented by indomethacin,

mefenamic acid, ibuprofen and the latest

nimesulide. Some antipyretics are anti-inflammatory, some are not while most have

pronounced analgesic properties. The decision to choose an antipyretic should be dictated by efficacy, safety, duration of effect

and cost.

One of the oldest antipyretics in use is

acetyl salicylic acid (ASA). The mode of

action of ASA is not wholly understood. It

inhibits cyclo-oxygenase which catalyses

the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin E2. This reduction of prostaglandin E2 in the brain is believed to lower the

hypothalamic set point. Since ASA also

possesses anti-inflammatory activity, this is

beneficial in patient with inflammatory

processes. Both the absolute (reduction of

initial temperature) and relative (in comparison to paracetamol or other drugs)

antipyretic efficacy of ASA in febrile children have been extensively evaluated(1418). Compared to paracetamol, ASA has

equal antipyretic efficacy. Differences in

the onset and duration of action may exist

for different doses, but similar doses of

each drug produced a similar time of onset

(0.6-0.9 hours) and duration of action (at

least 3 hours)(15). Adverse effects of ASA

after a single dose (hepatotoxicity) are also

known. Use of salicylates has demonstrated a strong statistical association with Reye

syndrome; patients with Reye syndrome

were found to have significantly higher total and average daily doses of salicylates

than matched controls(19). The easy avail-

VOLUME 34-MAY 1997

ability of ASA increases the chance of toxicity. Further, at therapeutic plasma levels,

ASA affects blood coagulation. Hence because of availability of equally potent and

safer drugs, ASA is currently not recommended as a first line antipyretic.

Another antipyretic in use for a considerable time is acetaminophen (paracetamol).

As with ASA, the antipyretic effect of

paracetamol is believed to be caused by its

ability to decrease prostaglandin synthesis

in the brain. Since paracetamol does not inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins in the

periphery, it does not possess any anti-inflammatory effects. Ibuprofen belongs to the

propionic acid group of NSAIDS. The

antipyretic effects of paracetamol and

ibuprofen have been compared in various

studies(20-26). The largest double blind acetaminophen controlled trial has established the safety of ibuprofen for

antipyresis in children. It involved 84192

children and proved that the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure or anaphylaxis was not increased following short

term use of ibuprofen(23). Some of these

studies have also shown a longer duration

of action for ibuprofen (8 hours) vis-a-vis

acetaminophen(20,22). In a dose of 10 mg/

kg, ibuprofen suspension, and possibly 5

mg/kg ibuprofen, produce equally tolerated, greater and longer lasting fever control

than 10 mg/kg paracetamol elixir, especially in children with oral temperatures above

100.5F(20). While further confirmatory evidence is awaited, ibuprofen liquid (10 mg/

kg) and paracetamol (15 mg/kg) administered every 6 hours for 24 to 48 hours appeared to be most effective in reducing fever. Lower ibuprofen doses (2.5 mg/kg

and 5 mg/kg) were less effective than

paracetamol and 10 mg/kg ibuprofen(24).

When administered every 6 hourly, there

was no significant difference between 10

mg/kg ibuprofen therapy and 15 mg/kg

paracetamol. Thus used in these doses, the

409

PERSONAL PRACTICE

above drugs are equally efficacious. Dose de-

pendent efficacy has also been found for

5,10 and 20 mg/kg paracetamol but the

duration of action differed in the trials performed^). More data are required from

prospective comparative trials together

with the recently adjusted higher dose and

shorter dosage intervals of acetaminophen.

There is only one study comparing the

antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen and

paracetamol in children wijih febrile seizures(28). Other studies in children

without

febrile

seizures

have

demonstrated

significantly

lower

temperatures at 3-5 hours after initial dose

of ibuprofen(29,30). Clinicians usually

pursue rapid fever reduction in children

with febrile seizures. In this respect a

0.5C greater temperature reduction at 4

hours was documented with ibuprofen.

Few recurrent seizures occurred in this

study and seizure prophylaxis was not

evaluated. No placebo controlled groups

were used. A large placebo controlled

trial is necessary to determine whether

antipyretics, especially ibuprofen can

prevent febrile seizure recurrences.

Dipyrone (Metamizol), a pyrazolone, is also

effective as an antipyretic. However, the

mechanism by which dipyrone exerts its

antipyretic effect is still unclear. It probably

has a direct action on the central nervous

system and possibly an additional peripheral inhibition of endogenous pyrogen synthesis and release. Double blind clinical trials on dipyrone are not available. The

antipyretic effect of this drug was compared with paracetamol in a single blind

controlled trial(31). Dipyrone in dose range

of 13.2 to 22.3 mg/kg was superior to

paracetamol (dose range 13.2-22.3 mg/kg)

1.5 hours to 6 hours after drug intake. The

only reported adverse effect of this drug is

agranulocytosis, the risk of which is approximately 1 per million per week of

treatment(32). However, because of contro410

versy raised over this, dipyrone is not

marketed in several countries. Most of the

reports dealing with the risk of agranulocytosis were based on observations of small

numbers of cases and matched controls(33,34). Additional graded dose comparative trials with dipyrone should be carried out in order to determine the optimum

dose for treating febrile children.

The latest drug Nimesulide (4-nitro-2phenoxymethane sulfonanilide) is a non

steroidal anti-inflammatory drug with analgesic and antipyretic properties. Its efficacy has been compared with naproxen,

ASA, paracetamol and mefenamic acid(3538). Though these demonstrated the superior efficacy of nimesulide, these studies

were not double blinded and comprised

small groups of children. More controlled

data is necessary before drawing any firm

conclusions. However, this drug may offer

a theoretical advantage of reduced frequency in dosing (8-12 hourly).

Corticosteroids are also highly effective

antipyretics. Although they have a place in

the treatment of certain infections wherein

the effects of inflammation may be devastating, their adverse effects on host defenses and risk of bowel perforation in inflammatory states have prevented them from

being used for antipyresis per se(39,40).

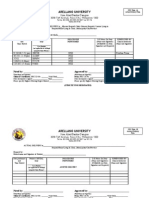

Table I summarizes the available pharmacological antipyretics with their age

wise recommended doses and frequency of

administration(37,41-43).

Recent data indicates that factors other

than the type of antipyretic agent employed are also important determinants of

the response to therapy. Multivariate analysis indicates that pharmacokinetics of

ibuprofen and perhaps all antipyretics are

determined by age and initial temperature(43). Thus if studies are conducted age

wise, using different doses of antipyretic

VOLUME 34-MAY 1997

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

TABLE IDose and Frequency of Administration of Commonly Used Antipyretics

Drug

Dose

Frequency of administration

Remarks

Ibuprofen(43)

10 mg/kg/dose

6-8 hourly

Age wise dose not stated

Nimesulide(37)

Acetyl salicylic

acid(42)

1.5 mg/kg/dose

30-65 mg/kg/

24 hours

8-12 hourly

4-6 hourly

Age wise dose not stated

Not recommended as first

line antipyretic

Paracetamol(41)

2-3 years

4-5 years

6-8 years

10 mg/kg/dose

12-15 mg/kg/dose

15-20 mg/kg/dose

4-6 hourly

4-6 hourly

4-6 hourly

Perhaps the safest

antipyretic

drugs over various temperature ranges,

clear cut differences may emerge regarding

their efficacy.

Fixed Dose Antipyretic Drug Combinations

Such combinations are commercially

available and are being aggressively promoted by some pharmaceutical companies.

Unfortunately, there is no concrete scientific data in the form of randomized controlled trials to guide the clinician regarding the utility or otherwise of such fixed

dose antipyretic drug combinations. Theoretically, a combination of two antipyretic

drugs may be expected to result in a greater antipyresis, analgesia and feeling of

"well being". However, this could also result in more risks of adverse effects. Further, the doses of antipyretics vary at different ages (especially paracetamol) and

formulation of optimal drug combinations

over the entire age range seems impossible.

It would therefore be prudent to avoid

fixed dose antipyretic drug combinations

until concrete scientific evidence to the contrary is available.

Concluding Comment

Prompt physical antipyresis is indicated

when temperature is to be lowered for a

reason not associated with true fever (heat

stroke, or induction of profound hypothermia in head trauma or cardiac surgery).

Further, antipyretic therapy is warranted

for dangerous hyperpyrexia (rectal temperature >41.1C) and fever in subjects with

precarious coronary perfusion (severe valvular heart disease). In the vast majority of

febrile infectious illnesses, there is no concrete evidence that fever is detrimental or

that antipyretic therapy offers any significant benefit. Despite this, in the actual clinical setting, antipyretic agents are invariably

prescribed for a combination of antipyresis,

analgesia and general feeling of "well being".

A variety of pharmocologic agents are

available for antipyresis. The so called superiority of one drug over the other is marginal and has no therapeutic significance.

Given in appropriate doses, ibuprofen and

paracetamol are equally efficacious and

safe. Pending the availability of firm scientific evidence, it would be prudent to avoid

fixed dose antipyretic drug combinations.

REFERENCES

1.

Endres S, Van der Meer JWM, Dinarallo

CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of

fever. Eur J Clin Invest 1987; 17: 467-474.

2.

Jampel HD, Duff GW, Gershon RK,

Atkins E, Durum SK. Fever and immuno

411

PERSONAL PRACTICE

regulation III: Fever augments the primary in vitro humoral immune response. J

Exp Med 1983; 157:1229-1238.

3.

Roberts NJ, Sandberg K. Hyperthermia

and human leukocyte migration inhibition factor (LIF). J Immun 1979; 122:19901993.

4.

Azocar J, Yunis EJ, Essex M. Sensitivity of

human

natural

killer

cells

to

hyperthermia. Lancet 1982; 1:16-17.

5.

Millichap JG. Studies in febrile seizures:

Height of body temperature-A measure of

the febrile seizure threshold. Pediatrics

1959; 23: 76-85.

phenol and acetyl salicylic acid. J Pediatr

1957; 50: 552-555.

17. Eden AN, Kaufman A. Clinical compari

son of three antipyretic agents. Amer J

Dis Child 1967,114: 284-287.

18.

Heremans G, Dehaen F, Rom M, Ramet J,

Verboven M, Loeb H. A single blind parallel group study investigating antipyretic

properties of ibuprofen syrup versus acetylsalicylic acid syrup in febrile children.

Br J Clin Prac 1988; 42: 245-247.

19.

Hurtwitz ES, Barett MJ, Bregman D,

Gunn W. Public Health Service study of

Reye syndrome and medications. Report

of the main study. JAMA 1987; 257: 19051911.

20.

Walson PD, Galleta G, Pharma D, Braden

NJ, Alexander L. lburopfen, acetaminophen and placebo treatment of febrile

children. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1989; 46: 917.

21.

Wilson JT, Brown D, Kearns GL, Eichler

VF, Johnson VA, Bertrand KM. Single

dose placebo controlled comparative

study of ibuprofen and acetaminophen

antipyresis in children. J Pediatr 1991;

119:803-811.

22.

Sheth UK, Gupta K, Paul T, Pispati PK.

Measurement of antipyretic activity of

ibuprofen and paracetamol in children. J

Clin Pharmacol 1980; 20: 672-675.

6.

Fishman MA. Febrile seizures: Treatment

controversy. J Pediatr 1979, 94: 177-184.

7.

Lipowski ZJ. Delirium (acute confusional

states). JAMA 1987, 258:1789-1792.

8.

Done AK. Treatment of fever in 1982: A

review. Am J Med 1983; 74 (Suppl): 27-35.

9.

Schmitt BD. Fever in childhood. Pediatrics 1984; 74 (Suppl): 929-936.

10.

Steel RW, Tanaka PT, Lara RP, Bass JW.

Evaluation of sponging and of oral

antipyretic therapy to reduce fever. J

Pediatr 1970; 77: 824-825.

11.

Aynsley GA, Pickerning D. Tepid spong

ing in pyrexia. Br Med J 1975; 2: 393-394.

12.

Newman J. Evaluation of sponging to reduce body temperature in febrile children. Can Med Assoc J 1985; 132: 641-642.

23.

Barbara S, Sugarman B. Antipyresis and

fever. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 15891597.

Lesko SM, Mitchell AA. An assessment of

the safety of Pediatric ibuprofen. JAMA

1995; 273: 929-933.

24.

Walson PD, Galleta G, Pharm D, Braden

NJ, Alexander L. Comparison of

multidose ibuprofen and acetaminophen

therapy in febrile children. Amer J Dis

Child 1992; 146: 626-632.

25.

Breart G. Jonville AP, Courcier S, Lassale

C, Goehrs JM. A comparative efficacy and

tolerance of ibuprofen syrup and acetaminophen syrup in children with pyrexia associated with infectious diseases and

treated with antibiotics. Clin Pharmacol

1994; 46:197-201.

13.

14.

Hunter J. Study of antipyretic therapy in

current use. Arch Dis Child 1973; 48: 313315.

15.

Tarlin L, Landrigan P. A comparison of

the antipyretic effect of Acetaminophen

and Aspirin. Amer J Dis Child 1972; 124:

880-882.

16.

Colgan MT, Mintz AA. The comparative

antipyretic effect of N acetyl-P-amino-

412

VOLUME 34-MAY 1997

INDIAN TEDIATRICS

26.

Ambedkar YK, Desai RZ. Antipyretic activity of ibuprofen and paracetamol in

children with pyrexia. Br ] Clin Prac 1985;

39:140-143.

27.

Adam D, Stankov G. Treatment of fever

in childhood. Eur J Pediatr 1994; 153: 394402.

28.

Esch AV, Henriette A, Moll VS,

Steyerberg EW, Offringa M, Habbema

DF. Antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen and

acetaminophen in children with febrile

seizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;

149: 632-637.

29.

Kauffman RE, Sawyer LA, Scheinbaum

ML. Antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen vs

acetaminophen. Amer J Dis Child 1992;

146: 622-625.

30.

Sidler J, Frey B, Baerlocher K. A double

blind comparison of ibuprofen and

paracetamol in juvenile pyrexia. Br J Clin

Pract 1990; 44 (Suppl 70): 22-25.

31.

Ottolegni A. Pediatric use of dipyrone as

an antipyretic agent. Minerva Pediatr

1971; 23:1981-1984.

32.

The International Agranulocytosis and

Aplastic Anemia Study. Risks of

agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia. A

first report of their relation to drug use

with special references to analgesics.

JAMA 1986; 256:1749-1757.

36.

Cappella L, Guerra A, Landizi L,

Cavazzuti GB. Efficacy and tolerability of

Nimesulide and Lysine Acetyl Salicylate

in the treatment of Pediatric acute upper

respiratory tract inflammation. Drugs

1993; 46 (Suppl 1): 222-225.

37.

Polidori G, Titti G, Pieragostini P, Comito

A, Scaricabarozzi I. A comparison of

Nimesulide and Paracetamol in the treat

ment of fever due to inflammatory diseases of the upper respiratory tract in

children. Drugs 1993; 46 (Suppl 1): 231233.

38.

Salzberg R, Giambonini S, Maurizio M,

Roulet D, Zahn J, Monti T. A double blind

comparison of Nimesulide and Mefenamic acid in the treatment of acute

upper respiratory tract infections in

children. Drugs 1993; 46 (Suppl 1): 208211.

39.

Mastersky J, Kass EH. Is suppression of

fever or hypothermia useful in experimental and clinical infectious disease? J

Infect Dis 1970; 121: 81-86.

40.

Rremine SG, Me Ilrath DC. Bowel perforation in steroid treated patients. Ann

Surg 1980; 192: 581-586.

41.

Wilson JT, Ksantikul V, Harbison R.

Death in an adolescent following an overdose

of

acetaminophen

and

phenobarbital. Am J Dis Child 1978; 132:

466-473.

33.

Discombe G. Agranulocytosis caused by

amidopyrone: An unavoidable cause of

death. BMJ1952,1:1270-1273.

34.

Huguley CH. Agranulocytosis induced

by dipyrone, a hazardous antipyretic and

analgesic. JAMA 1964; 189: 938-941.

42.

Done AK, Yaffe SJ, Clayton JM. Aspirin

dosage for infants and children. J Pediatr

1979; 95: 617-625.

35.

Rodriguez LES, Viveros HAA, Lujan ME.

Assessment of the efficacy and safety of

Nimesulide vs Naproxen in Pediatric patients with respiratory tract infection.

Drugs 1993; 46 (Suppl): 226-230.

43.

Brown RD, Wilson JT, Kearns JL, Pharm

D, Valarie F, Eichler RN. Single dose

pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in febrile children. J Clin

Pharmacol 1992; 32: 231-241.

413

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 05 N002 28712Dokumen17 halaman05 N002 28712Alfian FahrosiBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Efficacy and Tolerability of Acetaminophen Paracetamol and Mefenamic Acid As Antipyretic in Pediatric Pati PDFDokumen7 halamanEvaluation of Efficacy and Tolerability of Acetaminophen Paracetamol and Mefenamic Acid As Antipyretic in Pediatric Pati PDFrasdiantiBelum ada peringkat

- JournalReading - Learning Activity - Intrapartal Care - CamahalanDokumen3 halamanJournalReading - Learning Activity - Intrapartal Care - CamahalanJohn RyBelum ada peringkat

- Fever: Central Nervous System ConditionsDokumen14 halamanFever: Central Nervous System ConditionsthelordhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Inter Farkol 2.Dokumen13 halamanJurnal Inter Farkol 2.cahyamasita14Belum ada peringkat

- Lenhardt 09 PDFDokumen6 halamanLenhardt 09 PDFHarling MaysBelum ada peringkat

- Edwards AbstractDokumen3 halamanEdwards Abstracteen265Belum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy & Behavior: Jerome Niquet, Roger Baldwin, Michael Gezalian, Claude G. WasterlainDokumen5 halamanEpilepsy & Behavior: Jerome Niquet, Roger Baldwin, Michael Gezalian, Claude G. WasterlainCarinka VidañosBelum ada peringkat

- Mechanism of AntipyreticsDokumen12 halamanMechanism of AntipyreticsAnamaria Blaga PetreanBelum ada peringkat

- Topical Review: Hyperthermia Exacerbates Ischaemic Brain InjuryDokumen11 halamanTopical Review: Hyperthermia Exacerbates Ischaemic Brain Injuryspin_echoBelum ada peringkat

- Aronoff and Neilson - 2001 - Antipyretics Mechanisms of Action and Clinical UsDokumen12 halamanAronoff and Neilson - 2001 - Antipyretics Mechanisms of Action and Clinical UsstrijkijzerBelum ada peringkat

- Antipyretic: Drugs FeverDokumen3 halamanAntipyretic: Drugs Feverumesh123patilBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Fever in Critically Ill Patients With InfectionDokumen6 halamanManagement of Fever in Critically Ill Patients With InfectionAnonymous La9pmFYPBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraDokumen8 halamanDiagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraputryaBelum ada peringkat

- Fever: Pathophysiology and Clinical ApproachDokumen21 halamanFever: Pathophysiology and Clinical ApproachPooja ShashidharanBelum ada peringkat

- Fever During AnesthesiaDokumen19 halamanFever During AnesthesiaWindy SuryaBelum ada peringkat

- Mechanisms of Action, Physiological Effects, and Complications of HypothermiaDokumen17 halamanMechanisms of Action, Physiological Effects, and Complications of HypothermiaamaliaBelum ada peringkat

- 307 857 2 PBDokumen8 halaman307 857 2 PBBangkit Youga PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Intravenous Propacetamol On BL PDFDokumen6 halamanEffect of Intravenous Propacetamol On BL PDFRahmat ullahBelum ada peringkat

- Research ProposalDokumen4 halamanResearch Proposalapi-3215069410% (1)

- Scientifi C Evidence-Based Effects of Hydrotherapy On Various Systems of The BodyDokumen12 halamanScientifi C Evidence-Based Effects of Hydrotherapy On Various Systems of The BodyDeni MalikBelum ada peringkat

- Fever Pediatrics 2011Dokumen10 halamanFever Pediatrics 2011jmfbravoBelum ada peringkat

- PEA Glaucoma TreatmentDokumen9 halamanPEA Glaucoma TreatmentMenoddin shaikhBelum ada peringkat

- AntiDokumen29 halamanAntideepak_143Belum ada peringkat

- Hypothermia May Facilitate Liver Transplant in Patients With Increased Intracranial PressureDokumen18 halamanHypothermia May Facilitate Liver Transplant in Patients With Increased Intracranial Pressurexai_teovisioBelum ada peringkat

- ¿Who's Afraid of FeverDokumen6 halaman¿Who's Afraid of FeverJosep Bras MarquillasBelum ada peringkat

- Pharmacological Management of FeverDokumen6 halamanPharmacological Management of FeverNabillaMerdikaPutriKusumaBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Neonatal Morbidities During Hypothermia Treatment 2015Dokumen6 halamanManagement of Neonatal Morbidities During Hypothermia Treatment 2015Vanessa CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Therapeutic HypothermiaDokumen7 halamanTherapeutic HypothermiaTracyBelum ada peringkat

- Fever: The Long and Short of It: Denise Goh Li MengDokumen5 halamanFever: The Long and Short of It: Denise Goh Li MengPuannita SariBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Anatomy and Physiology - Febrile SeizureDokumen17 halamanReview of Anatomy and Physiology - Febrile SeizureSundaraBharathi75% (4)

- Pediatrics: Fever and Antipyretic Use in ChildrenDokumen10 halamanPediatrics: Fever and Antipyretic Use in Childrenramon_otto6228100% (1)

- NursingCareinFever VrdiNorden1996Dokumen5 halamanNursingCareinFever VrdiNorden1996Pritam MajiBelum ada peringkat

- BFCDokumen7 halamanBFCKalvinKonOjalesStrangerBelum ada peringkat

- HTTPS:WWW - scielosp.org:PDF:Bwho:2003.v81n5:372 374Dokumen3 halamanHTTPS:WWW - scielosp.org:PDF:Bwho:2003.v81n5:372 374tinosan3Belum ada peringkat

- Swamedikasi DemamDokumen25 halamanSwamedikasi DemamrosawpBelum ada peringkat

- The Ice Bath Path To Enhanced Sperm Health And Fertility - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Ice Baths And Male Reproductive HealthDari EverandThe Ice Bath Path To Enhanced Sperm Health And Fertility - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Ice Baths And Male Reproductive HealthBelum ada peringkat

- Paracetamol Suppositories: Should We Give It As Antipyretic in Children?Dokumen27 halamanParacetamol Suppositories: Should We Give It As Antipyretic in Children?Arrum Chyntia YuliyantiBelum ada peringkat

- Anestesia de Paciente PediátricoDokumen4 halamanAnestesia de Paciente PediátricoPollín GrinshBelum ada peringkat

- Cerebro Lys inDokumen18 halamanCerebro Lys inKathleen PalomariaBelum ada peringkat

- OTC Advisor - Fever, Cough, Cold, and Allergy FINAL PDFDokumen33 halamanOTC Advisor - Fever, Cough, Cold, and Allergy FINAL PDFmorsi0% (1)

- 0812 Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy PDFDokumen35 halaman0812 Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy PDFPutriBelum ada peringkat

- Antipyretic Therapy: K.E. ElizabethDokumen1 halamanAntipyretic Therapy: K.E. ElizabethShruthi KyBelum ada peringkat

- 0091 - 010 - Fever and The Inflammatory ResponseDokumen6 halaman0091 - 010 - Fever and The Inflammatory ResponsePedro Rodriguez ABelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review Febrile SeizureDokumen6 halamanLiterature Review Febrile SeizureArdyanto WijayaBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Terapi Rendam Kaki PDFDokumen7 halamanJurnal Terapi Rendam Kaki PDFFIRMAN SYAH PERMADIBelum ada peringkat

- Targeted Temperature Management in Brain Injured  Patients PDFDokumen23 halamanTargeted Temperature Management in Brain Injured  Patients PDFCamilo Benavides BurbanoBelum ada peringkat

- Urits2019 Article AComprehensiveUpdateOfCurrentADokumen10 halamanUrits2019 Article AComprehensiveUpdateOfCurrentAyantiBelum ada peringkat

- Thermal Hydrotherapy Improves Quality of Life and Hemodynamic Function in Patients With Chronic Heart FailureDokumen6 halamanThermal Hydrotherapy Improves Quality of Life and Hemodynamic Function in Patients With Chronic Heart FailurearitabrunoBelum ada peringkat

- NursingCareinFever VrdiNorden1996Dokumen5 halamanNursingCareinFever VrdiNorden1996hany abo fofaBelum ada peringkat

- (Ingles) Aproximación Febril en El Paciente en UCIDokumen14 halaman(Ingles) Aproximación Febril en El Paciente en UCIRoberto Augusto Laos OlaecheaBelum ada peringkat

- Thermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateDokumen17 halamanThermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateWinny Shiru MachiraBelum ada peringkat

- Prostaglandin and Endorphin Levels in Adolescent Primary Dismenore Given Warm and Cold HydrotherapyDokumen7 halamanProstaglandin and Endorphin Levels in Adolescent Primary Dismenore Given Warm and Cold HydrotherapyRoro RatuningrumBelum ada peringkat

- Febrile SeizureDokumen8 halamanFebrile Seizureanon_944507650Belum ada peringkat

- Voluntary Activation of The Sympathetic Nervous System and Attenuation of The Innate Immune Response in HumansDokumen6 halamanVoluntary Activation of The Sympathetic Nervous System and Attenuation of The Innate Immune Response in HumansGerson De La FuenteBelum ada peringkat

- Manejo de La Sepsis 2Dokumen5 halamanManejo de La Sepsis 2Rachmi Pratiwi Febrita PartiBelum ada peringkat

- Fernandez, John Michael BSN403 Group 10: I. Clinical QuestionDokumen5 halamanFernandez, John Michael BSN403 Group 10: I. Clinical QuestionJohn Michael FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Hypothermia Pa Tho PhysiologyDokumen11 halamanHypothermia Pa Tho Physiologygvazquez85Belum ada peringkat

- Drug Fever - UpToDateDokumen17 halamanDrug Fever - UpToDatehgeniauxBelum ada peringkat

- Improving EyesightDokumen2 halamanImproving Eyesight2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Technical Specialist Interview Questions: Topinterviewquestions - InfoDokumen11 halamanTechnical Specialist Interview Questions: Topinterviewquestions - Info2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Yoga and CelibacyDokumen7 halamanYoga and CelibacyIvan CilerBelum ada peringkat

- Words of WisdomDokumen2 halamanWords of Wisdom2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Improving EyesightDokumen2 halamanImproving Eyesight2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- MCITP Windows Admin Interview QuestionsDokumen20 halamanMCITP Windows Admin Interview Questions2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- VNC For Secure ConnectionsDokumen1 halamanVNC For Secure Connections2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Old Sayings Quotes and QuipsDokumen9 halamanOld Sayings Quotes and Quips2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Acharya, Brajaratna - Vedic MantrasiddhiDokumen59 halamanAcharya, Brajaratna - Vedic Mantrasiddhi2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Ebook - Hack - Discovery NmapDokumen16 halamanEbook - Hack - Discovery Nmapapi-26021296100% (3)

- IpnatDokumen1 halamanIpnat2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Golden Dawn - Meditation With The Archangel GabrielDokumen2 halamanGolden Dawn - Meditation With The Archangel GabrielSargeras777100% (4)

- DruggedDokumen2 halamanDrugged2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Lab2 LectureDokumen57 halamanLab2 Lecture2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Shrimad Valmiki Ramayan SKT Hindi DpSharma Vol07 YuddhaKandaPurvardh 1927Dokumen739 halamanShrimad Valmiki Ramayan SKT Hindi DpSharma Vol07 YuddhaKandaPurvardh 1927rudragni108100% (1)

- Rife FrequenciesDokumen3 halamanRife Frequencies2 Funky88% (16)

- Ipf HowtoDokumen56 halamanIpf Howto2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Ashta Lakshmi StotramDokumen3 halamanAshta Lakshmi Stotramsindhu.s88% (8)

- Tantra of The Great Liberation: This Version of Mahanirvana Tantra (Edition 1913) Has Been Coping FromDokumen14 halamanTantra of The Great Liberation: This Version of Mahanirvana Tantra (Edition 1913) Has Been Coping From2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Ak 200401 YoginisDokumen2 halamanAk 200401 Yoginis2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Shrimad Valmiki Ramayan SKT Hindi DpSharma Vol07 YuddhaKandaPurvardh 1927Dokumen739 halamanShrimad Valmiki Ramayan SKT Hindi DpSharma Vol07 YuddhaKandaPurvardh 1927rudragni108100% (1)

- 72 Spirits From Weyer &CDokumen2 halaman72 Spirits From Weyer &C2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Ashta Lakshmi StotramDokumen3 halamanAshta Lakshmi Stotramsindhu.s88% (8)

- Filter SamplesDokumen8 halamanFilter Samples2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Jataka ChandrikaDokumen14 halamanJataka ChandrikalovershivaBelum ada peringkat

- Ashtavakra GitaDokumen9 halamanAshtavakra GitaNikul JoshiBelum ada peringkat

- Tantra of The Great Liberation: This Version of Mahanirvana Tantra (Edition 1913) Has Been Coping FromDokumen14 halamanTantra of The Great Liberation: This Version of Mahanirvana Tantra (Edition 1913) Has Been Coping From2 FunkyBelum ada peringkat

- Julie-Ann Amos - Be Prepared! Pass That Job Interview (4th Ed.) (2009)Dokumen97 halamanJulie-Ann Amos - Be Prepared! Pass That Job Interview (4th Ed.) (2009)Cristian JimboreanBelum ada peringkat

- Qameic Seals of The ArchangelsDokumen6 halamanQameic Seals of The Archangelsasterion32100% (6)

- On Call Survival Guide PDFDokumen78 halamanOn Call Survival Guide PDFBangun Said SantosoBelum ada peringkat

- Design Consideration in Reducing Stress in RPDDokumen11 halamanDesign Consideration in Reducing Stress in RPDAnkit NarolaBelum ada peringkat

- Flight Surgeon BrochureDokumen2 halamanFlight Surgeon BrochurejohnsmartsBelum ada peringkat

- Notes GITDokumen7 halamanNotes GITEhsanTamizBelum ada peringkat

- Neonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital Physicians Neonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital PhysiciansDokumen75 halamanNeonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital Physicians Neonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital PhysiciansSebastian SpatariuBelum ada peringkat

- Websites For Review of RadiologyDokumen1 halamanWebsites For Review of RadiologyHaluk AlibazogluBelum ada peringkat

- Egyptian Hospital Accreditation Program: Standards: Sixth Edition May 2005Dokumen71 halamanEgyptian Hospital Accreditation Program: Standards: Sixth Edition May 2005khayisamBelum ada peringkat

- KaranDokumen6 halamanKaranogidoBelum ada peringkat

- Medical and Mental Health NeedsDokumen10 halamanMedical and Mental Health NeedsKim OlsenBelum ada peringkat

- NPWT RENASYS and PICO Clinical GuidelinesDokumen78 halamanNPWT RENASYS and PICO Clinical GuidelinesAgung GinanjarBelum ada peringkat

- PLLV Client Consent FormDokumen4 halamanPLLV Client Consent Formapi-237715517Belum ada peringkat

- A LilingDokumen3 halamanA LilingJohn Vincent Dy OcampoBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Cobalamin and Folate DisordersDokumen6 halamanGuidelines For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Cobalamin and Folate DisordersOndire PatrickBelum ada peringkat

- Fluoride TherapyDokumen4 halamanFluoride TherapyمعتزباللهBelum ada peringkat

- Androgenetic Alopecia and Coronary Artery Disease CASE CONTROL STUDY DR RAHUL KUMAR SHARMA SKIN SPECIALIST AJMERDokumen2 halamanAndrogenetic Alopecia and Coronary Artery Disease CASE CONTROL STUDY DR RAHUL KUMAR SHARMA SKIN SPECIALIST AJMERRahul SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Css Rizky Rafiqoh Afdin InggrisDokumen19 halamanCss Rizky Rafiqoh Afdin InggrisSyukri Be DeBelum ada peringkat

- Faculty of Medicine - Cairo University Program Specification For MBBCH (2010-2011)Dokumen11 halamanFaculty of Medicine - Cairo University Program Specification For MBBCH (2010-2011)Osama MahfouzBelum ada peringkat

- Neonatology Today May 2023 NeoHeart at WCDokumen332 halamanNeonatology Today May 2023 NeoHeart at WCTANDO JAM THE GREATBelum ada peringkat

- LMRASSIGNMENTDokumen2 halamanLMRASSIGNMENTjaoBelum ada peringkat

- Arellano University: Jose Abad Santos CampusDokumen7 halamanArellano University: Jose Abad Santos CampusLloyd VargasBelum ada peringkat

- Canadian Journal of Emergency MedicineDokumen4 halamanCanadian Journal of Emergency MedicineWily GustafiantoBelum ada peringkat

- Lipa Muz Ter 05 eDokumen82 halamanLipa Muz Ter 05 ezero LinBelum ada peringkat

- ScheduleDokumen7 halamanScheduleJigar AnadkatBelum ada peringkat

- Shoes and Techniques Hans - April - 2014Dokumen214 halamanShoes and Techniques Hans - April - 2014L.E. Velez97% (39)

- Pulmonary EdemaDokumen28 halamanPulmonary EdemaMohammed Elias100% (1)

- Speech & Language Therapy in Practice, Spring 1999Dokumen32 halamanSpeech & Language Therapy in Practice, Spring 1999Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeBelum ada peringkat

- Singh 2016 PDFDokumen2 halamanSingh 2016 PDFAffina Noor RasyidyaBelum ada peringkat

- 1319 FullDokumen5 halaman1319 FullFreddy Campos SotoBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontal Case StudyDokumen26 halamanPeriodontal Case StudySwapnilSauravBelum ada peringkat

- Sudden Onset Leg PainDokumen16 halamanSudden Onset Leg PainNafisNomanBelum ada peringkat