An Adaptation With Fangs Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

Diunggah oleh

Mite StefoskiHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

An Adaptation With Fangs Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

Diunggah oleh

Mite StefoskiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

1 11

Vol 2

Issue 20

16 Dec

2002

KINOEYE

home

this issue

about us

contributing

vacancies

contact us

E-MAIL

UPDATES

enter e-mail

subscribe

more info

ARCHIVES

search

english title

original title

director

article list

journal list

add a link

COUNTRY

ARCHIVES

country

HORROR

An adaptation with fangs

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht

(Nosferatu the Vampyre, 1979)

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom

der Nacht

(Nosferatu the

Vampyre, 1979)

Detailing the cultural background,

production history, and critical reception

of Herzog's Nosferatu remake, Garrett

Chaffin-Quiray explains the film's

complex relationship to the horror genre

while providing insight into the

filmmaker's "purposefully austere

aspiration to beauty."

Strangeness has always been Herzog's major theme. A

friend of mine once told me that she heard Herzog

claim he wanted the world to appear in his films as it

would to a Martian who just arrived on Earth. His

method for achieving this is incongruity. [1]

A view from today

On 26 October 2002 I visited Manhattan's Cathedral Church of

Saint John the Divine for the "Halloween Extravaganza &

Procession of Ghouls." An annual production, the conclusion of the

night's program was a puppet parade. Directly preceding this

exhibition, though, was a screening of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's

1922 classic Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu, A

Symphony of Horrors) with a live organ accompaniment.

Having previously seen Murnau's film, I anticipated a creaking relic

of histrionic acting and anachronistic special effects. Indeed, I

watched the film while listening to alternating snickers of

disappointment and simultaneous thrills of wonder in a crowd

several hundred strong. As a result, I was reminded of the

importance of context concerning Nosferatu with some eighty years

having passed between now and its original release.

SEARCH

go

Subsequently I binged on all things of unholy origin. I read reviews,

fingered library books and compared images handed down through

a lifetime spent consuming vampire movies. In so doing, I

completed the Nosferatu trifecta.

After attending the Cathedral Church screening, but only after

HORROR IN

KINOEYE

Films

Claire Denis'

Trouble Every

Day (2001)

Jrg Buttgereit's

Nekromantik

(1987) &

Nekromantik 2

(1991)

Oliver

Hirschbiegel's

Das Experiment

(2001)

Carl-Theodor

Dreyer's

Vampyr (1931)

and Lucio

Fulci's E tu

vivrai nel

terrore

L'aldil

(1981)

Werner

Herzog's

Nosferatu:

Phantom der

Nacht (1979)

Agustn

Villaronga's

Tras el cristal

(1986)

Ingmar

Bergman's

Persona (1966)

Ulli Lommel's

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

2 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

reading Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, I watched Werner

Herzog's 1979 adaptation, Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht and

finished off with E Elias Merhige's insider-peek-cum-alternativehistory, Shadow of the Vampire (2000). What follows, then, is the

result of my dive into the subject at hand.

Frames of reference

What we recognise as das neue Kino, or the New German Cinema,

was a movement born from generational conflict. Following

Germany's defeat in World War II, the coherence of its national

identity was split among occupying allied powers, just as the

country was riven with foreign cultural products, sold piecemeal to

external combines and dwarfed by memories of its former status

under Adolph Hitler.

Along with the rapid Americanisation of West Germany confronting

Soviet-styled East Germany, there was a coincident malaise about

the unassimilated Nazi past, the "unbewltige Vergangenheit."

Turning the war generation against its offspring, another baby

boom, Germany's future was a portrait of contradiction, not least

because the Holocaust prosecuted during the war led directly to the

post-war Economic Miracle.

German cinema, itself a reflection of national sensibilities, exhibited

these tensions on-screen. Decimated by an exhausting war effort,

filmmakers in the 1940s largely produced works of narrow interest.

Continental development and the popularity of television expanded

the canvas just as a backlash against Hollywood's control over local

movies was unleashed.

At the Oberhausen Film Festival of 1962, "an acute sense of

alienation and anomie"[2] bubbled to the surface. Alexander Kluge

and Norbert Kckelmann, both filmmakers and spokesmen for the

unrest, shaped the moment and lambasted the conventional system.

One result was the Oberhausen Manifesto aimed at disrupting

then-current cinematic practice.

Finding American dollars easy to secure for distribution and

exhibition channels, though not for investment in local movie

production, the Oberhausen group envisioned a way out from under

their cultural colonisation. Lobbying the Budestag, or West German

parliament, they successfully set up the Koratorium Junger

Deutscher Film (Young German Film Board), to support funding

and distribution of members' work along with establishing film

schools in Munich and Berlin and an archive in Berlin. From

1965-1968, the Koratorium supported the debut of several dozen

new filmmakers. Yet the fundamentally inconsistent source of film

finance continued to haunt das neue Kino.

One method to solve the problem was the Film Frderungsanstalt

(FFA), which gave money to film producers according to fairly

Zrtlichkeit der

Wlfe (1973)

Victor Trivas's

Der Nackte und

der Satan

(1959)

Lars von Trier's

Forbrydelsens

Element (1984)

Maurice

Tourneur's La

Main du diable

(1942)

Roman

Polanski's Le

Locataire

(1976)

Rumle

Hammerich's

Svart Lucia

(1992)

Ji Svoboda's

Proklet domu

Hajn (1988)

Guillaume

Radot's Le Loup

des Malveneur

(1942)

Stefan

Ruzowitzky's

Anatomie

(2001)

Themes

The

international

reception of

Hannibal

Jan

vankmajer's

"agit-scare"

tactics

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

3 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

loose standards and which led to soft-core porn and sex comedies.

The second method was an FFA reform, the Filmberlad der Autoren

(Author's Film-Publishing Group), a private company intended to

distribute members' films with monies collected from television

network subsidies and tithes, and to ensure artistic products with

careful sponsorship. A fertile period resulted and the world was

introduced to filmmakers like Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner

Fassbinder and Werner Herzog, although they were typically only

celebrated abroad in countries like France and America.

The youngest of these prominent three, Wenders, was born on 14

August 1945. Stylistically his work tends to blend Hollywood genres

while thematically exploring the Americanisation of post-war

Germany in pictures like Der Amerikanische Freund (The

American Friend, 1977) and Der Himmel ber Berlin (Wings of

Desire, 1987).

Fassbinder, the middle child whose death is commonly regarded as

the end of das neue Kino, was born on 31 May 1945 and overdosed

on 10 June 1982. Multi-generic in scope, his movies reference

1950s Hollywood melodramas overlaid with spot-on social

criticism. Detractors malign his prolific output as indistinguishable

from Hollywood's conventions while admirers argue he both

satisfies and subverts spectatorial expectations in films such as

Angst essen Seele auf (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, 1974) and Die Ehe

der Maria Braun (The Marriage of Maria Braun, 1978).

Italian wax

dummies as

inspiration for

horror

Of mad love,

alien hands and

the film under

your skin

Festivals

Brussels

International

Fantastic Film

Festival

Lupo Frightfest,

London

Interviews

Horror Actor

Reggie Nalder

Herzog, the oldest of the trio, was born Werner Stipetic on 5

September 1942. A "holy fool," [3] he possesses a legendary need

to confront danger. His well-documented production difficulties

forever shadow his work, in which fans admire grand landscapes

and enigmatic heroes while detractors see self-indulgence,

recklessness and failure of storytelling.

"King of

Schlock" Roger

Corman in

Europe

Though his biography is riddled with hyperbole, the general facts

suggest he grew up in a remote Bavarian village, wrote his first

script at 15 and made his first short film at 17. To earn money he

worked blue-collar jobs. Eventually he earned a Fulbright

scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, where he studied film

and television. In 1964 he won the Carl Mayer Prize for promising

screenplays, finally making his feature debut four years later with

Lebenszeichen (Signs of Life, 1968).

Special issues

During this period, vacillating (as the rest of his career always has)

between documentary impulses, poetic grandeur and epic journeys

into the souls of madmen, Herzog offered a pithy aphorism about

the cinema for which he is famous: "Film is not the art of scholars,

but of illiterates." [4] Such an idea is useful for unpacking Herzog's

fascination with Murnau's silent classic.

Cognisant of his fame, with its particular focus after Aguirre, der

Zorn Gottes (Aguirre, the Wrath of God, 1974), Herzog recognised

the shifting climate of film finance and production. Namely, "a

Strach

Czech film's

love affair with

fear and horror

Blood poetry

The cinema of

Jean Rollin

Assault on the

senses

The horror

legacy of Dario

Argento

The hidden

face of horror

Georges

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

4 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

major problem for the filmmakers of das neue Kino was

distribution. While the Film Subsidies Board generously supported

independent production of all sorts, the films of the New German

Cinema grew too elaborate and too numerous for the exhibition

outlets available to them." [5] To fill the void and continue making

movies, many enterprising, even exploitive, filmmakers like Herzog

cultivated international co-financing deals coupled with certain

artistic concessions, especially yoked to Hollywood. As Timothy

Corrigan writes,

The connection with the Hollywood circuit and the

audience it controls throughout the world is...a crucial

dimension not only of Herzog's work but of the entire

New German Cinema. As much as its filmmakers were

nurtured by their strained relation with their pre-war

forefathers like Lang and Murnau, the historical and

economic roots of contemporary German film were,

formed during the postwar 1950s when American

occupation of West Germany fostered a peculiarly

displaced relation between the two cultures. [6]

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom der

Nacht (Nosferatu the

Vampyre, 1979)

Franju's Les

Yeux sans

visage

Three from

Mario Bava

Three on Tesis

Archive

Visit Kinoeye's

Horror

Archive

Enter Nosferatu, a recognised title

in the cinematic pantheon, a

European co-production between

Werner Herzog Filmproduktion,

Gaumont and ZDF, and with a fully

enabled distribution channel

provided by Twentieth Century

Fox.

The boon was a production budget

of DEM 2.5 million (USD 1.4

million), the biggest in Herzog's

career to that time, [7] along with

an international release to existing

syndicates and a cast and crew

ready to risk the remake. The

sufferance, however, was a

dual-language production shot simultaneously in English and

German, maintenance of the irascible Klaus Kinski as star and an

ongoing struggle to live up to Murnau's original upon which

Herzog's picture could be pilloried.

Child of the night

Unable to shoot in Bremen, as Murnau did in 1922, Herzog

contracted the Dutch town of Delft. Embittered over memories of

Nazi occupation, though, the Delft citizenry were less than

enthusiastic about hosting a German production crew. When

Herzog finally announced plans to release 11,000 rats for a

particularly important scene, Delft's city fathers refused him after

citing their extensive efforts to rid the city of vermin.

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

5 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

Inconvenienced, Herzog moved his production, along with its

Hungarian-bred white lab rats painted gray for the sake of realism,

to the more accommodating Dutch city of Schiedam.

At the same time, Kinski was enduring several hours of daily

make-up to enliven his part as Count Dracula, although he was also

weathering a personal hell. Estranged from his third wife, he

laboured under the knowledge she was about to divorce him, taking

with her their son. Everywhere mythologised as being wildly manic

in his habits, Herzog managed to help channel his star's private pain

into a form of helplessness more conducive to the part.

The resulting film is not a clear copy of its source, though it does

offer an occasional shot-for-shot echo. "It is an homage to the 1922

Murnau classic of the same name, from which it is freely adapted,

and is thereby a tribute to the purity of vision of the silent cinema

and also a lament of the loss of innocence represented by Bram

Stoker's original 1897 novel, 'Dracula.'"[8] Developing the idea of

lost innocence, Herzog's version makes a careful nod to female

empowerment, offers a dystopian finale suggesting total failure and

employs the relative richness of colour film stock and a recorded

soundtrack.

Opening in Wismar, we meet Jonathan

Harker (Bruno Ganz), a property clerk newly

wed to Lucy (Isabelle Adjani), for whom he

wishes to provide a comfortable home. When

a large commission is offered to him for

transacting with the far-off Count Dracula

(Kinski), Jonathan eagerly accepts the job.

Werner

Herzog's

Nosferatu:

Phantom der

Nacht

(Nosferatu the

Vampyre, 1979)

After an arduous month traveling through the

Carpathian Mountains, he stops at a roadside

inn for refreshment before meeting the

Count. Mentioning his client by name, the

establishment falls silent before Jonathan listens to rumors of

Nosferatu. He discounts such talk as peasantry run amuck and soon

meets the Count, a lonely and unloved "man." Very quickly,

Dracula becomes fascinated by a photograph of Lucy and accepts

Jonathan's offered property, which makes them neighbours. Long

nights ensue and the Count begins feasting on his clerk before

sailing for Wismar, bringing with him death and the plague in an

army of rats.

Jonathan belatedly realises Dracula's threat but loses his memory

while returning home because he is gradually stricken with

vampirism. Arriving after the plague has already been loosed,

bodies pile up in the city square and Jonathan is delivered into

Lucy's care, vegetative and absent of any love for his bride.

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom

der Nacht (Nosferatu

Faced with the destruction of her

world, Lucy contacts Dr Van Helsing

(Walter Ladengast) requesting help,

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

6 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

but is ultimately forced to act alone.

She researches Dracula's whereabouts

and uncovers his weaknesses, killing

him through self-sacrifice as a sensual

meal under the cast of morning

sunlight. Unfortunately, Jonathan is already made the Count's

successor and is last seen riding into the stretch of tomorrow,

unmarked by his past life or the original ambition that drove him to

the Count in the first place.

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom

der Nacht (Nosferatu

the Vampyre, 1979)

Then versus now

Enjoying a debut in Paris on 10 January 1979, Nosferatu was a

mixed viewing experience. Though it received the Berlin

International Film Festival's Silver Bear for Outstanding Single

Achievement in production design for Henning von Gierke and a

nomination for the Golden Bear for Herzog, and though Kinski

received a German Film Award for Outstanding Individual

Achievement in acting, critics and viewers alike were troubled by

the picture.

Perhaps best summarising the issue, William Wolf wrote,

"Unquestionably Herzog's version is a stylistic triumph. But do we

need yet another encounter with the count?" [9] Vincent Canby

echoed the sentiment and wrote, "Mr Herzog has done what he set

out to do, but when you come right down to it, one wonders if it's

worth the trouble. Dracula, after all, is not Hamlet or Othello or

Macbeth. He's not some profoundly complex character who speaks

to us in more voices than most of us care to hear. Dracula is Santa

Claus turned mean. He's a fairy-tale character. Though he

represents something vestigially scary, he's not endlessly

interesting." [10]

Given these indirectly complimentary remarks responding to a

late-1970s spate of vampire motion pictures (including John

Badham's Dracula [1979] and Stan Dagoti's Love at First Bite

[1979]), and a certain reverence towards Murnau's original, the

critical reaction divided among those preferring 1922's version to

that of 1979. Pondering the adaptation, Ernest Leogrande asked,

"What was its special fascination for Herzog?" [11] before serving

judgement: "Murnau's version still stands above Herzog's. The 1922

movie is a tidy little package that causes viewers to marvel at the

sophistication of its technique even when they're laughing at the

broad-stroke silent movie acting, acting that incidentally adds to he

movie's charm." [12]

His pleasure at outmoded acting styles notwithstanding, Donald

Barthelme roughly agreed, writing, "The problem here is that

Herzog was unable to bring new life to his much-handled material."

[13] "But comparisons are unnecessary in sizing up this new

Dracula tale as a major disappointment, often pictorially striking but

singularly unengrossing," [14] continued a Variety reviewer who

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

7 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

equally placed the film in a wider social context. "The renewed

vogue for Dracula vehicles will give Herzog's film a certain

commercial success, though there will undoubtedly be many

disappointed spectators. Herzog is being true only to himself, which

will continue to delight his followers and further alienate his

detractors." [15]

Yet while detractors clung to artistic primacy in Murnau, or else to

a general dislike of Herzog due to an avoidance of horror film

tropes conventionalised in the 1970s-including gore, jarring

soundtracks and fast editing for kinesis-fans like David Denby

perceptively gathered how "the young German director has made

not a conventional horror film (there are no shocks) but an

anguished poem of death." [16] Herzog's undead monster is a

threatening force from the deep well of Nature, even as he is an

obviously self-centred killer of men. But he is also a deeply

sympathetic monster spurned by a blood lust of unusual proportion

and buoyed by the desire to die while lacking any method for

accomplishing that end.

For Jack Kroll, "When the Dracula figure lurches ashore in FW

Murnau's classic 1922 'Nosferatu,' carrying his coffin filled with

native earth, it was a chilling premonition of Hitler's imperialism of

death, the desire to necropolize the world. Following Murnau,

Herzog's 'Nosferatu' mixes such resonances with a surprisingly

successful attempt to humanize Dracula." [17] It follows that

Herzog's film "can...be appreciated as a contemplative work of art

rather than as a horror thriller, which it is not," [18] because "the

familiar becomes arrestingly odd; ineffable mystery is presented as

the basic of condition of human life." [19]

Associative editing practices display this

Werner Herzog's

mystery in connecting Lucy with

Nosferatu: Phantom

Dracula, her nightmares of flying bats to

der Nacht (Nosferatu

his hunger suggested in the shadow play

the Vampyre, 1979)

of his fingertips. Beauty thus inscribes

the beast who, for all his cruelty and

deathly intentions, wishes only to

ingratiate himself to the ethereal woman

(Adjani) and receive her honest

affection. "Where the nightmare

exaggerations of Murnau, preditary [sic]

wolves, Venus flytraps, the rat-like

vampire and his kingdom of vermin are

easily recuperated into a scheme of

symbols for a repressed but vital Nature, Herzog's expressionism is

pure spirit, a sulfuric image of hell." [20] Though readable as a

continuous symptom of the unassimilated Nazi past, the alwaysalready present capacity of evil, symbolised by Dracula, is a

condition defining the goodness of humanity, as attributed to Lucy.

What detractors and supporters both remark on is the powerful use

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

8 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

of images in the film. Arguments about the superiority or inferiority

of Herzog's production are interesting conversation pieces.

Typically burdened by tautological assumptions, however, little can

be gleaned from such comparison since the real value of panning or

praising it comes from noting what it succeeds at over and above

what was possible in Murnau's moment.

Reflecting on the Count

Critic John Azzopardi has claimed that Herzog's Nosferatu is, "one

of the greatest horror films ever made." [21] Though clearly a

judgement call, his remark has merit, especially when one considers

the picture itself and in particular the cinematography of Jrg

Schmidt-Reitwein. Rich in the distinctions of dull colours bleeding

between light brown, yellow, white and occasional splashes of blue,

Herzog's picture moves through Wismar into Transylvania with an

accompanying change in palate. Colours grow darker, red appears,

the Count dominates the screen and time slows to long takes of

shadow and inexplicable shapes in the night.

Also, none of what appears in the film is precisely horrific. At least

not in the way of nightmares or much of what audiences and critics

expected of any self-titled horror movie in 1979. Still, Kinski's

performance, surely one of the richest of his career, is both nuanced

and other. Dracula is obviously pained by his very existence, but

like any animal capable of surviving the gaps between discomfort

and salvation, he consumes his way through the lack of love and is

finally ground up in the sacrifice of an innocent equal to his evil

incarnate.

While a symptomatic reading yields the vampire as analogous to das

neue Kino's relationship with Hollywood, one of endless

colonisation and co-optation of changing local circumstances to its

own end, I think such a reading is off the deep end. So too is the

implicit lesson of how primal human nature can be perpetually

tamed by virgin sacrifice. Even notions about how unbewltige

Vergangenheit appears within the text, informing characterisation,

is far-fetched since the film responds more to the socio-cultural

conditions of the 1970s than it does to World War II, or even to the

post-World War I moment that offered Murnau his inspiration.

Instead, what I find most rewarding is the visual, and to a lesser

extent aural, wash that is Nosferatu's overall affect. Because art for

its own sake is often a dead end, Herzog's purposefully austere

aspiration to beauty still trades on generic expectation to offer

familiar, though slightly unconventional thrills.

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom der

Nacht (Nosferatu the

Vampyre, 1979)

Remembering his attitude about the

cinema being meant for illiterate

spectators, the motive for a

slow-moving spectacle seems

obvious. Images appear and linger,

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

9 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

eliciting a visceral reaction without

having to support cause and effect.

Throughout the film, visual

storytelling takes centre stage away

from a more literary approach

because the script is deliberately

slim. By capitalising on a

well-known narrative, the plot is

thus everywhere revealed through action, movement and the

constantly changing colouring, lighting and emotional pattern of the

cinematic canvas.

Werner Herzog's

Nosferatu: Phantom der

Nacht (Nosferatu the

Vampyre, 1979)

In short, the effort to transport an audience into the space of

reflection and wonder is what makes Herzog's adaptation of Stoker's

monster via Murnau's camera into something of value. Nowhere is

this more obvious than in the dominant image of the film, indeed of

the entire Stoker-derived vampire franchise. When Kinski's tortured

monster first appears, but even more impressively when he hunts

Lucy in her bedroom, he becomes one of the master icons of the

cinema. His extended fingertips and open mouth outline his

monstrosity turned into familiar desire and materialise our repressed

fantasies, neither spoken nor dictated in everyday life. As a result,

Nosferatu is part of us and Herzog's film reflects on this condition

with impressive vigour.

Garrett Chaffin-Quiray

Also of interest

Kinoeye articles on the legacy of Europe's Nazi past as a

horror motif:

Germany's secret history:

Stefan Ruzowitzky's Anatomie (Anatomy, 2000)

A closet full of brutality

Volker Schlndorff's Der Junge Trless (Young Torless,

1966)

Dr Franju's "House of Pain" and the political cutting

edge of horror

Georges Franju's Les Yeux sans visage (Eyes without a

Face, 1959)

Conspicuous consumption:

Ulli Lommel's Zrtlichkeit der Wlfe (Tenderness of the

Wolves, 1973)

Power, paedophilia, perdition: Agustn Villaronga's

Tras el cristal (In a Glass Cage, 1986)

See also:

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

10 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

Horror film in Kinoeye and on the web

About the author

Garrett Chaffin-Quiray was educated at the University of

Southern California School of Cinema-Television. Having

sponsored a film festival, taught courses on TV and cinema

history and published variously, his research interests include

pornography, American cinema and the 1970s. He is also a

novelist and former information technologist.

return to the Kinoeye home page

return to the main page for this issue

Footnotes

1.Nol Carroll, "Creatures of the Night." The Echo Weekly News

(11 October 1979): 35.

2.David A Cook, A History of Narrative Film (3rd ed) (New York

& London: WW Norton & Company, 1996), 661.

3.David Robinson, The History of World Cinema (revised and

updated ed) (New York: Stein and Day, 1981), 375.

4. Alan Greenberg, Herbert Achternbush and Werner Herzog,

Heart of Glass (Munich: Skellig, 1976), 174.

5. Cook, 681.

6. The Films of Werner Herzog: Between Mirage and History, ed

Timothy Corrigan (New York and London: Methuen, 1986), 7.

7. Ibid, 217.

8. Kevin Thomas, "New 'Nosferatu' a Tribute to Murnau." Los

Angeles Times (29 October 1979): D35.

9.William Wolf, "Nosferatu, the Vampyre." Cue New York (26

October 1979): 19.

10. Vincent Canby, "Screen: 'Nosferatu,' Herzog's Dracula." New

York Times (1 October 1979): C15.

11. Ernest Leogrande, "The chills are hollow." New York Daily

News (4 October 1979): 87.

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Kinoeye| German film: Werner Herzog's Nosferatu

11 11

http://www.kinoeye.org/02/20/chaffinquiray20.php

12. Ibid.

13. Donald Barthelme, "Nosferatu." The New Yorker (15 October

1979): 182-84 (184).

14.Variety, "'Nosferatu: Phantom Der Nacht' ('Nosferatu, The

Vampire')" (24 January 1979): 23.

15.Ibid.

16.David Denby, "Nosferatu." New York (22 October 1979): 89.

17.Jack Kroll, "Thinking Man's Count Dracula." Newsweek (15

October 1979): 133.

18. Andrew Sarris, "The Real McCoy." The Village Voice (8

October 1979): 40.

19.Carroll, 35.

20. John Azzopardi,"Herzog: Last Breath Of German

Expressionism." Chelsea News (18 October 1979): 11. The writer's

choice of spelling is quoted intact.

21.Ibid.

Copyright Kinoeye 2001-2011

11-Mar-11 09:21 PM

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Адонис обраќање (Меридијани) англискиDokumen2 halamanАдонис обраќање (Меридијани) англискиMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- Saint Joan of Arc On A PostcardDokumen4 halamanSaint Joan of Arc On A PostcardMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- Book For WineDokumen19 halamanBook For WineMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- Paavo Haavikko and T Omas T Ranströmer Selected PoemsDokumen126 halamanPaavo Haavikko and T Omas T Ranströmer Selected PoemsMite Stefoski100% (1)

- Adonis Excerpt PDFDokumen76 halamanAdonis Excerpt PDFd alkassimBelum ada peringkat

- A Portrait Without A FrameDokumen9 halamanA Portrait Without A FrameMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- The French Connection Final DraftDokumen94 halamanThe French Connection Final DraftMite Stefoski100% (1)

- The PianistDokumen92 halamanThe PianistUser26652Belum ada peringkat

- ANNIE HALL Screenplay by Woody AllenDokumen136 halamanANNIE HALL Screenplay by Woody AllenMite Stefoski100% (3)

- STORYTELLING Screenplay by Todd SolondzDokumen54 halamanSTORYTELLING Screenplay by Todd SolondzMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- Nashville ScriptDokumen88 halamanNashville ScriptMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- The Truman Show Screenplay ByAndrew M. NiccolDokumen99 halamanThe Truman Show Screenplay ByAndrew M. NiccolMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- Schindler's ListDokumen116 halamanSchindler's Listpatch295Belum ada peringkat

- The Piano Lesson Screenplay by Jane CampionDokumen79 halamanThe Piano Lesson Screenplay by Jane CampionMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- BEING JOHN MALKOVICH Screenplay by Charlie KaufmanDokumen70 halamanBEING JOHN MALKOVICH Screenplay by Charlie KaufmanMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- The Shining - A Stanley Kubrick FilmDokumen146 halamanThe Shining - A Stanley Kubrick FilmMite Stefoski75% (4)

- The Third Man Screenplay by Graham GreeneDokumen203 halamanThe Third Man Screenplay by Graham GreeneMite Stefoski100% (1)

- Taxi̇ Driver ScriptDokumen114 halamanTaxi̇ Driver ScriptMustafa IzistanbulaBelum ada peringkat

- Mean Street SEASON of The WITCH Screenplay by MARTIN SCORSESE, Mardik Martin, Ethan EdwardsDokumen98 halamanMean Street SEASON of The WITCH Screenplay by MARTIN SCORSESE, Mardik Martin, Ethan EdwardsMite StefoskiBelum ada peringkat

- MEMENTO A Film by Cristopher Nollan (Script)Dokumen142 halamanMEMENTO A Film by Cristopher Nollan (Script)Mite Stefoski100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

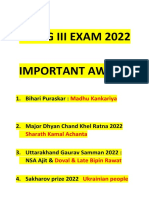

- Awards 2022Dokumen17 halamanAwards 2022Armstrong SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Lit. AssignmentDokumen5 halamanLit. AssignmentJasonBelum ada peringkat

- Final Exam Basic 5Dokumen3 halamanFinal Exam Basic 5Fabry R CastellBelum ada peringkat

- Discover China SB2 Scope & Sequence - KamalDokumen4 halamanDiscover China SB2 Scope & Sequence - KamalFuture LearningBelum ada peringkat

- Willy Wonka DissertationDokumen6 halamanWilly Wonka DissertationOnlinePaperWriterSingapore100% (1)

- Miklós Szentkuthy - Towards The One and Only Metaphor (Sample)Dokumen82 halamanMiklós Szentkuthy - Towards The One and Only Metaphor (Sample)louiscoraxBelum ada peringkat

- 11Dokumen2 halaman11Matthew RoseBelum ada peringkat

- Uhon Lear NotesDokumen7 halamanUhon Lear NotesGreg O'DeaBelum ada peringkat

- Epic TheatreDokumen5 halamanEpic Theatremjones4171100% (2)

- A2 Lit Essay Writing TechniquesDokumen2 halamanA2 Lit Essay Writing TechniquesAndrew Wang100% (1)

- Great GatsbyDokumen31 halamanGreat GatsbyKis-Toth Tamas50% (2)

- Narrative StoryDokumen2 halamanNarrative StoryMeatSpin100% (1)

- Our Complete Reading ListDokumen22 halamanOur Complete Reading Listfourshopping89% (9)

- The Frozen ThroneDokumen4 halamanThe Frozen ThroneHarley David Reyes Blanco100% (1)

- French EssayDokumen2 halamanFrench Essaygooklba0% (1)

- Bài tập tìm lỗi sai- Ôn thi HKIDokumen4 halamanBài tập tìm lỗi sai- Ôn thi HKIThai Thi Hong LoanBelum ada peringkat

- PenmanshipDokumen246 halamanPenmanshipCristina75% (4)

- SodaPDF Merged Merging ResultDokumen87 halamanSodaPDF Merged Merging ResultMa.Terrisa Paula DeanonBelum ada peringkat

- Hades and PersephoneDokumen11 halamanHades and PersephoneMarvin RinonBelum ada peringkat

- German 0Dokumen202 halamanGerman 0Madhu MidhaBelum ada peringkat

- How To Make Them Love PDFDokumen1 halamanHow To Make Them Love PDFkeithwashingtonmanagement0Belum ada peringkat

- Ebook1028 EbookDokumen270 halamanEbook1028 EbookShivaram Kulkarni100% (1)

- Bolick Karen Assessment ProjectDokumen11 halamanBolick Karen Assessment Projectapi-240694863Belum ada peringkat

- Star Trek - ALL - The Five EnterprisesDokumen64 halamanStar Trek - ALL - The Five EnterprisesRobert VilesBelum ada peringkat

- As I Lie AwakeDokumen200 halamanAs I Lie AwakeviideriBelum ada peringkat

- Lizard FolkDokumen7 halamanLizard FolkAdam AldredBelum ada peringkat

- Wide Angle Recommended ReadersDokumen6 halamanWide Angle Recommended ReadersbilmazlarBelum ada peringkat

- Explaining The (A) Telicity Property of English Verb PhrasesDokumen15 halamanExplaining The (A) Telicity Property of English Verb PhrasesjmfontanaBelum ada peringkat

- Amanda!: Robin KleinDokumen24 halamanAmanda!: Robin KleinAymaanBelum ada peringkat