Femur Fractures in The Pediatric Population: Abuse or Accidental Trauma?

Diunggah oleh

bocah_britpopDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Femur Fractures in The Pediatric Population: Abuse or Accidental Trauma?

Diunggah oleh

bocah_britpopHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Clin Orthop Relat Res (2011) 469:798804

DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1339-z

SYMPOSIUM: NONACCIDENTAL TRAUMA IN CHILDREN

Femur Fractures in the Pediatric Population

Abuse or Accidental Trauma?

Keith Baldwin MD, MPH, MSPT, Nirav K. Pandya MD,

Hayley Wolfgruber BA, Denis S. Drummond MD,

Harish S. Hosalkar MD, MBMS (Ortho), FCPS (Ortho), DNB (Ortho)

Published online: 7 April 2010

The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com

Abstract

Background Child abuse represents a serious threat to the

health and well-being of the pediatric population. Orthopaedic specialists will often become involved when child

abuse is suspected as a result of the presence of bony

injury. Distinguishing abuse from accidental trauma can be

difficult and is often based on clinical suspicion.

Questions/purposes We sought to determine whether

accidental femur fractures in pediatric patients younger

than age 4 could be distinguished from child abuse using a

combination of presumed risk factors from the history,

physical examination findings, radiographic findings, and

age.

Methods We searched our institutions SCAN (Suspected

Child Abuse and Neglect) and trauma databases. We

identified 70 patients in whom the etiology of their femur

fracture was abuse and compared that group with 139

patients who had a femur fracture in whom accidental

trauma was the etiology.

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations

(eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing

arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection

with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human

protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted

in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed

consent for participation in the study was obtained.

K. Baldwin, N. K. Pandya, H. Wolfgruber,

D. S. Drummond, H. S. Hosalkar

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Childrens Hospital

of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

H. S. Hosalkar (&)

Rady Childrens Hospital, UCSD, 3030 Childrens Way,

Suite 410, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

e-mail: HHOSALKAR@rchsd.org

123

Results A history suspicious for abuse, physical or

radiographic evidence of prior injury, and age younger than

18 months were risk factors for abuse. Patients with no risk

factors had a 4% chance, patients with one risk factor had a

29% chance, patients with two risk factors had an 87%

chance, and patients with all three risk factors had a 92%

chance of their femur fracture being a result of abuse.

Conclusions Clinicians can use this predictive model to

guide judgment and referral to social services when seeing

femur fractures in very young children in the emergency

room.

Level of Evidence Level III, diagnostic study. See

Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels

of evidence.

Introduction

Orthopaedic surgeons play a critical role in evaluating

potential cases of child abuse because fractures represent

the second most common presentation of abuse behind

only soft tissue injuries [23]. There are numerous studies

that have focused on the characteristics of fractures considered typical of abuse, including fractures of the femur

[1, 4, 5, 9, 14, 19, 28, 29], humerus [3, 12, 19, 31], tibia

[4, 12, 18], and ribs [6, 33]. Yet, orthopaedic surgeons are

less likely than general pediatric and emergency room

colleagues to identify abuse as the potential etiology of

these fractures, thus causing delay for appropriate multidisciplinary intervention [15, 26]. This is concerning

because of the million children annually in the United

States who are the victims of substantiated abuse, orthopaedic surgeons are often the first clinicians to evaluate

these patients, and if the cause of injury is not recognized,

these children will return to an abusive environment with a

Volume 469, Number 3, March 2011

50% risk for reinjury and a 10% risk of death [7, 13]. It is

therefore essential orthopaedic surgeons not only treat the

fractures these children present with, but also recognize the

associated etiologic characteristics of the injury that may

suggest child abuse.

When examining a fracture in the emergency room, the

following questions should arise: What patient characteristics may be indicative of abuse versus accidental trauma?

Is the history and mechanism of injury inconsistent with

the presenting injury? Does this fracture type, pattern, and

location represent potential abuse? Fractures of the femur

in young children provide an ideal model to develop a

systematic examination process to differentiate an abusive

from accidental etiology.

Fracture of the femur in children is the most common

musculoskeletal injury requiring hospitalization [5, 20].

Numerous studies describe fractures of the femur in young

children, and many of these have attempted to identify

fracture characteristics that may indicate abuse [2, 5, 8, 11,

20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29]. The most common presentation

cited is the presence of a femur fracture in a patient

occurring either before walking age or before the second

birthday [5, 9, 13, 20, 28, 30]. In addition, several authors

have classified the radiographic appearance and location of

femur fractures as predictors of abuse [2, 15, 25, 28, 29] as

well as elements of the history (inconsistent history,

inappropriate delay, multiple presentations), physical

examination (examination inconsistent with history, head

injury or fracture in a child not of walking age), and

socioeconomic background [16, 22, 32]. A number of other

reports previously examined fracture patterns in children

younger than 48 months of age [6, 14, 16, 17, 26]. These

studies do not, however, allow a clinician to decide with

confidence whether a given femur fracture is likely caused

by abuse.

We therefore asked whether femur fractures caused by

abusive trauma could be distinguished from those caused

by accidental trauma using presumed risk factors in the

history, physical examination, and radiographic characteristics. We then built a predictive model based on those

factors.

Materials and Methods

Our institution is a large pediatric tertiary care center with

Level I trauma status with a large referral base. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before data

collection. Since 1998, we have maintained an extensive

database (Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect [SCAN])

that examines all potential cases of suspected child abuse

and/or neglect. This database contains information identifying child abuse victims, demographic factors, and ICD-9

Femur Fractures in the Pediatric Population

799

and CPT codes relating to their concomitant diagnoses and

treatment. From that database, we identified all children

from birth to 48 months of age who had the diagnosis of

child abuse (ICD-9 code 995.5x) and the diagnosis of

femur fracture (ICD-9 code 820.x and 821.x). In addition,

we reviewed the general trauma database from our institution for all children presenting to the emergency room

and/or hospitalized with traumatic injuries for children of

the same age from 2000 to 2003 with the diagnosis of

femur fracture (ICD-9 code 820.x and 821.x). The general

trauma database contains data identifying trauma patients

that fit these characteristics, demographic information,

information regarding injury diagnoses, and subsequent

treatment. Information other than demographic information, injury code data and identifying information were

abstracted from the electronic medical record.

We calculated a power analysis for multiple logistic

regression as described by Hsieh et al. [10]. The power

analysis assumes a background abuse rate of 30% [9] in

patients with femur fractures in this age group with a difference in the rate in any given independent variable of

20%. The power analysis was conducted with a desired

two-sided alpha of 0.05 and a desired power of 0.80. The

analysis assumes a variance inflation rate (adjustment for

increased variability caused by multiple regressors) of 25%

for multiple regression. With these characteristics, our total

sample size would need to be 196 patients. Because our

analysis assumes a 30% event (abuse) [9] rate in femur

fractures, we would need 30% of our total cases to be from

abuse and 70% from accidental trauma (59 abuse cases and

137 accidental trauma cases).

Patients were identified in the study as a potential control (accidental) trauma case if they were found in the

general trauma database and did not have a diagnosis of

child abuse in their record and were not included in the

SCAN database. We excluded patients from the study if

they were younger than 48 months of age (except for one

patient, the SCAN database contained only patients

48 months of age and younger), if we could not adequately

confirm whether the case represented child abuse or accidental injury as a result of incomplete medical records

(three children), and if cases were erroneously placed in

either of the two databases (ie, did not represent either

child abuse or accidental trauma). This was the case in one

child in whom a diagnosis of femur fracture by ICD-9 code

was found but no record of this injury could be identified.

In addition, we excluded patients with known metabolic

bone disease or osteogenesis imperfecta. Seventy femur

fractures were from the child abuse cohort and 139 femur

fractures were from the accidental trauma cohort. These

209 total femur fractures represented the cases and controls

that would be analyzed in our study. The child abuse cohort

had a median age of 4.0 months. Of these 70 patients, 63

123

800

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research1

Baldwin et al.

were younger than 18 months of age and seven were older

than 18 months of age. The accidental trauma cohort had a

mean age of 26.2 months. Of these 139 patients, 44 were

younger than 18 months of age and 95 were older than

18 months of age.

Patients were included in the SCAN database if hospital

personnel determined the patient was a victim of abuse or

neglect. The SCAN team consisted of an independent

group of nonorthopaedic physicians, nurses, and social

workers with advanced training in child abuse who

examined these children independently in the emergency

room and/or as inpatients and made the determination

whether the patients should be diagnosed with child abuse

and when child protective services should be activated.

Patients were included in the general trauma database if

they presented to the emergency room and/or were hospitalized with organ system trauma that necessitated an

evaluation from the hospitals trauma service, died in the

emergency department as a result of their traumatic injuries, or were initially seen in the emergency department

and transferred to another trauma center for management of

traumatic injuries. Both databases were collected and

maintained outside of the orthopaedic department at our

institution and were initiated many years before the retrospective review of the data that was performed by the

authors.

Data parameters collected from the patients medical

records included age at the time of injury, gender, insurance status, presence of current polytrauma (another

concurrent long bone, clavicle or axial skeletal fracture, or

other body system injury that would require hospitalization), and physical and/or radiographic evidence of prior

trauma. Furthermore, one of the authors (HW) who was

blinded to the SCAN status of patients examined the paper

and electronic medical records of the children and briefly

described the history of each patient. Subsequently, this

author categorized in a separate list the plausibility of each

patients history as either suspicious for abuse (unwitnessed accident, witnessed abuse, delayed presentation

greater than 48 hours, a mechanism that would not normally cause a fracture, or different stories provided by

different witnesses), or consistent with accidental trauma in

cases in which these criteria were not fulfilled, and then

transferred the list to the database. Two other authors (NP

and KB) reviewed the patient histories to determine if they

were consistent with accidental trauma or suspicious for

abuse. An intraclass correlation coefficient was generated

based on average measures (ICC 0.902, p value \ 0.001)

indicating agreement. Since many of the original radiographs for patients were no longer available, we examined

radiology reports to determine the location of the femur

fracture in all patients. The fractures were classified as

proximal, diaphyseal, or distal (each representing

roughly one-third of the length of the femur: subtrochanteric region, shaft region, and distal metaphyseal region).

Raw data from the databases were pooled, and means,

SDs, and/or percentages were calculated for age at time of

injury, gender, insurance status, presence of current polytrauma, physical and/or radiographic evidence of prior

trauma, history plausibility (consistent with accidental

trauma or suspicious for abuse), and radiographic femur

fracture location (proximal, diaphyseal, distal).

Because our age data were skewed we used the Mann

Whitney U test for independent samples to determine if

there was a difference in age at the time of injury between

the child abuse and accidental trauma patients. The chi

square test with Yates correction for independence or the

Fishers exact test in cases where the assumptions of a chi

square test were violated were used to determine differences in binary variables. We used binary logistic

regression to calculate adjusted odds ratios for a femur

fracture representing abuse as opposed to accidental trauma

using age at time of injury, gender, insurance status,

presence of current polytrauma, physical and/or radiographic evidence of prior trauma, history plausibility, and

femur fracture location as risk factors. Ninety-five percent

confidence intervals were calculated for proportions and

interquartile ranges for median values.

Child abuse victims were younger than accidental

trauma victims (median age 4.0 months compared with

26.2 months) and were more often female (49% versus

32%) (Table 1). There was no difference (p = 0.77)

between the abuse and accidental trauma groups in terms of

insurance status. Patients with femur fractures who were

Table 1. Demographic information for child abuse and accidental trauma patients for age, gender, and insurance status

Variable

All abuse (95% CI)

All accidental

Odds ratio (95% CI)

Number of patients

70

139

N/A

N/A

Age younger than 18 months

90.0% (83.0%, 97.0%)

31.7% (23.9%, 39.4%)

19.4 (8.3, 45.0)

\ 0.001*

Age (months)

4.0 (2.0, 8.3**)

26.2 (11.9, 34.8**)

N/A

\ 0.001

Gender (percent female)

Percentage without insurance

48.6 % (36.9%, 60.2%)

7.1% (1.1%, 13.2%)

32.4% (24.6%, 40.2%)

9.4% (4.5%, 14.2%)

2.0 (1.1, 3.6)

0.7 (0.3, 2.1)

0.033*

0.795

* Chi square test with Yates correction; Mann Whitney U test; Fishers exact test; **Interquartile range N/A = not applicable.

123

p value

Volume 469, Number 3, March 2011

Femur Fractures in the Pediatric Population

801

Table 2. Comparison of current polytrauma, prior trauma, and history plausibility in child abuse and accidental trauma patients with femur

fractures

Variable

Number

of abuses

Percent abuse

(95% CI)

Number accidental

trauma

Percent accident

(95% CI)

Odds ratio

(95% CI)

p value

\ 0.001*

Current polytrauma

37/70

52.8% (41.2%, 52.9%)

11/139

7.9% (3.4%, 12.4%)

13.0 (6.1, 28.1)

Physical and/or radiologic

evidence of prior trauma

44/70

62.3% (51.5%, 74.2%)

6/139

4.3% (0.9%, 7.7%)

37.5 (14.8, 94.7) \ 0.001*

History suspicious for abuse

23/70

32.9% (21.9%, 43.9%)

6/139

4.3% (0.9%, 7.7%)

10.8 (4.3, 27.5)

\ 0.001*

Raw number in parentheses; p values generated by Yates chi square test for independence; *statistically significant.

Table 3. Comparison of femur fracture location in child abuse and accidental trauma patients

Variable

Number

of abuses

Percent abuse

(95% CI)

Accidental

trauma

Percent accident

(95% CI)

Odds ratio

(95% CI)

p value

Proximal femur

14/70

20.0% (10.6%, 29.4%)

19/139

13.7% (8.0%, 19.4%)

1.5 (0.7, 3.3)

0.33

Femoral diaphyseal

32/70

45.7% (34.0%, 53.4%)

92/139

66.1% (58.3%, 74.1%)

0.4 (0.2, 0.8)

0.007*

Distal femur

26/70

37.1% (25.8%, 48.5%)

28/139

20.1% (13.5%, 26.8%)

2.3 (1.2, 4.4)

0.01*

Raw number in parentheses; p values generated by Yates; chi square test for independence; odds ratios compare patients who are positive for

each fracture type as the outcome and abuse as the risk factor; *statistically significant.

victims of abuse had a greater frequency of current polytrauma (53% versus 8%), physical and/or radiographic

evidence of prior trauma (62% versus 4%), and histories

that were deemed suspicious for abuse (33% versus 4%)

(Table 2). Patients with accidental trauma more often had

diaphyseal femur fractures (46% versus 66%), abuse victims more often had distal femur fractures (37% versus

20%), and there was no difference in proximal femur

fractures between groups (Table 3). The odds of a femur

fracture being the result of abuse rather than accidental

trauma was greater for children younger than 18 months

(19.4 times) and patients of female gender (2.0 times)

(Table 1). Furthermore, abuse was associated more frequently with current polytrauma (13.0 times), physical and/

or radiographic evidence of prior trauma (37.5 times), and

patients with a suspicious history (10.8 times) (Table 2).

Finally, we used a multiple logistic regression model to

calculate a prediction rule for the chance of abuse given the

aforementioned risk factors. All of the variables that were

significant in any portion of the study were used. In addition, variables previously judged important were included

in the initial multiple logistic regression model. The variables were entered using the backward likelihood ratio

method for selection of variables. All variables were

entered and criteria of 0.10 by the 2 log likelihood

method was used for removal of variables. In the backward

regression analysis, only age younger than 18 months,

physical and/or radiographic evidence of prior injury, and

history of plausibility were predictive of an abusive etiology for child abuse. In this model, patients with a femur

Table 4. Multiple logistic regression model with number of risk

factors (risk factors: age younger than 18 months, physical and/or

radiologic evidence of prior trauma, and suspicious history)

Variable

Beta

statistic

Odds ratio

(95% confidence interval)

p value

One risk factor

2.0

7.2 (2.223.5)

\ 0.001*

Two risk factors

5.0

155.5 (41.6581.0)

\ 0.001*

Three risk factors

5.6

273.0 (28.12649.0)

\ 0.001*

* Statistically significant.

fracture whose age was younger than 18 months had a 10

times greater chance of being the victim of abuse than

older children. Patients who had the presence of prior

trauma on physical and/or radiographic examination had a

16.8 times greater chance of having been a victim of abuse

than patients who had no such findings. Finally, patients

with a suspicious history had a 7.4 times greater chance of

having been abused than patients with a plausible history

after considering the other factors in the model.

Given these findings, a new simpler logistic regression

model was built based on the outcome of the first model

(Table 4). This model was built with the three significant

variables in the first model. The variables entered were

whether the patient had one, two, or three risk factors (risk

factors from the first model: age younger than 18 months,

physical and/or radiographic evidence of old trauma, and

history suspicious for abuse). This final model did not

differ (p = 0.69) from the old model using the 2 log

likelihood method of comparison.

123

802

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research1

Baldwin et al.

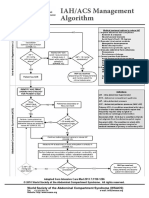

PATIENT PRESENTS TO CLINIC OR EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

WITH FEMUR FRACTURE

CLINICIAN ASSESSES NUMBER OF RISK FACTORS FROM

FOLLOWING LIST:

1) AGE < 18 MONTHS

2) PHYSICAL AND/OR RADIOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE OF PRIOR

TRAUMA

3) SUSPICIOUS HISTORY

0 RISK

FACTORS

4.2%

1 RISK

FACTOR

2 RISK

FACTORS

24.1 %

87.2%

RISK OF ABUSIVE

FEMUR FRACTURE

3 RISK

FACTORS

92.3%

Fig. 1 The figure shows our algorithm for determining whether a

femur fracture stems from abuse or accidental trauma based on our

regression model.

Results

A simple model using number of risk factors (age younger

than 18 months, physical or radiographic evidence of prior

injury, and suspicious history) predicted abuse in this age

group. Odds ratios were calculated based on the logistic

regression model versus a patient with no risk factors

(Table 4).

The logistic regression equation was then solved for each

number of risk factors to develop a prediction tool. In our

population, patients with no risk factors had a 4% chance of

having abuse as the etiology for their femur fracture, patients

with one risk factor had a 24% chance abuse was the etiology

of their femur fracture, patients with two risk factors had an

87% chance abuse was the etiology of their femur fracture,

and patients with three risk factors had a 92% chance abuse

was the etiology of their femur fracture (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Pediatric femur fractures are the most common musculoskeletal injury requiring hospitalization [5, 20], and their

presence in children raises suspicion for abuse [2, 5, 8, 11,

20, 21, 24, 28, 29]. In fact, it has been proposed that onethird of femur fractures in children younger than age

4 years and 80% of femur fractures in children who are not

yet walking have an abusive etiology [9]. Multiple studies

have attempted to classify the demographic and fracture

characteristics of children whose fracture may have an

abusive etiology, including age (particularly before walking age or the second birthday) [5, 9, 13, 20, 28, 30],

123

radiographic appearance and location of the fracture [2, 15,

28, 29] as well as elements of the history, physical examination, and socioeconomic background [16, 22, 32].

Because femur fractures are a common entity that the

orthopaedic clinician will evaluate in the emergency room

and are linked to child abuse [2, 5, 8, 11, 20, 21, 24, 28,

29], it is essential for the orthopaedic clinician to be able to

differentiate an abusive from an accidental etiology so that

proper multidisciplinary action can be initiated to protect

children from an abusive environment. In light of this fact,

and the fact that one recent investigation suggests fracture

pattern may not be as useful in determining fracture etiology [29], there exists no prediction algorithm with which

to help a clinician assign etiology to an injury. We presumed femur fractures resulting from accidental trauma

could be differentiated from femur fractures resulting from

abuse using history, physical examination, demographic

factors, and radiographic findings, and a prediction model

based on these parameters can be generated to allow clinicians to more accurately identify victims of abuse and

distinguish abuse from accidental trauma.

There are several limitations in our study. First, our

prediction rule was generated from an urban Level I pediatric trauma center. It is unclear if the prediction rule would

be different for pediatric patients presenting to lower-level

pediatric trauma centers in nonurban environments and/or

in different countries. However, our tertiary referral status

allows us to say we attract patients from a broad catchment

area, hence enhancing our external validity. Second, it can

be argued our assessment of history status (consistent versus

suspicious) is subjective. Specifically, arguments for mitigating individual circumstances such as unwitnessed injury

could be due to a momentary lapse in supervision; delay in

seeking care could be due to lack of health insurance or a

child who is not expressing substantial discomfort. However, our criteria for suspicion are consistent with previous

reports [6, 27, 30]. In addition, although our blinded rater

was instructed to look at only the history and physical

records to determine the patient history without viewing

other aspects of the medical record, she was not strictly

blind to the SCAN status of the patient because she had

access to the medical record. The use of corroborating

investigators with a high intraclass correlation coefficient

somewhat mitigates this risk. Third, as a result of the fact

that child abuse is largely a social diagnosis, there exists no

test that can confirm the presence or absence of child abuse

with a high level of specificity or sensitivity. Yet, we

believe evaluation by independent specialists constitutes the

best method available in the current literature. Inclusion in

the SCAN database is determined by an independent group

of social workers, nurses, and physicians who all have

advanced training in child abuse (and are independent from

the authors) at the time the child presents to the emergency

Volume 469, Number 3, March 2011

Femur Fractures in the Pediatric Population

room, and is also used for a clinical purpose (ie, activating

child protective interventions). As with any study of child

abuse, the study risks circuitous logic, that is to say, child

abuse is often diagnosed by suspicious history, physical

examination findings, and other social factors. However,

this could be said about any condition that is a clinical

diagnosis; as such, we believe guidelines for diagnosis of

this condition are helpful.

The use of age, history, physical findings, and radiographic findings to assess for child abuse is not new

(Table 5). Although these multiple characteristics are

essential in providing a general picture of a pediatric

patient presenting with child abuse, the question arises as to

how these characteristics can be applied in a quantifiable,

objective manner to help to reliably predict etiology for a

clinician. Whereas other studies have limited their analysis

803

to descriptions of abusive and accidental femur fracture, the

prediction model developed from our study allows for

research to be translated into clinical action. Of the multiple

demographic characteristics in our study, the multiple

regression model identified the following three predictors

after accounting for other confounders when differentiating

abusive from accidental femur fractures in this age group:

(1) age younger than 18 months; (2) physical and/or

radiographic evidence of prior trauma; and (3) history

suspicious for abuse. Clinicians can use this rule in the

following fashion: patients with no risk factors have a 4%

chance of having a femur fracture stemming from child

abuse; patients with one risk factor have a 24% chance;

those with two risk factors have an 87% chance; and those

with three risk factors have a 92% chance of having a femur

fracture stemming from abuse.

Table 5. Risk factors found to be important or used to help diagnose child abuse

First

author

Age as a risk factor

for abuse

Historical features

Physical examination Radiographic

features

or other features

Anatomic location

Coffey

67% (extremity

et al. [4]

injuries were in

patients younger

than 18 months)

N/A

N/A

N/A

Not available within specific fracture

groups

Rex and

92% (younger than

Kay [28]

1 year)

N/A

N/A

N/A

No difference in site of fracture

(proximal/middle/distal)

Schwend

et al.

[30]

42% of children

younger than

walking age with

femur fractures

Suspicious, inconsistent Bruises or

history or delayed

polytrauma

presentation used to

characterize

Multiple fractures

All were shaft fractures

Leventhal

et al.

[17]

60% (younger than

1 year femur

fractures)

Suspicious history,

None listed for

change in behavior

femurs

or Medicaid payor

None listed for

femurs

None listed for femur fractures

Suspicious, inconsistent Bruises or multiple

history or delayed

injuries

presentation

Multiple fractures

No specific pattern, study speaks in

terms of fracture plausibility

N/A

N/A

Pierce et al. 50% younger than

[27]

1 year with

probable abuse.

Loder and 15% (younger than

N/A

Bookout

2 years)*

[18]

Scherl et al. 13% of total cohort, Suspicious history

[29]

but average age of

confirmed abuse

0.83 years

N/A

Bilateral injuries

Associated injuries

worked up more

often, but only 1/7

were positive

No particular distribution

Fong et al.

[6]

52% of abuse

patients younger

than 3 years old

(all fractures)

Suspicious, inconsistent None specified

history or delayed

presentation

Fractures in various No anatomic distribution noted

stages of healing

within femur fractures

Worlock

et al.

[33]

80% abusive

fractures in those

younger than

18 months

No historical

Bruising of the head Rib fractures in the 50% metaphyseal chip in the femur

information available

and neck

absence of chest

in abuse patients; in other long

trauma, multiple

bones, spiral or oblique fractures

fractures

more common

Baldwin

et al.

[current

study]

90% abused children Inconsistent or

Consistent with other Consistent with

younger than

suspicious history, or

injuries or prior

prior injury

18 months

delayed presentation

injury

Distal more often abuse shaft more

often accident

* Based on the 2000 kids inpatient database; N/A = no available data in the study.

123

804

Baldwin et al.

It is essential for clinicians to be able to differentiate

the etiology of pediatric femur fractures as stemming

from abuse or accidental trauma. Not only are femur

fractures a common injury seen by orthopaedic clinicians,

but identification of the etiology of the injury is vital to

ensure proper multidisciplinary intervention can be initiated for the safety of the child. Prediction based on the

multiple logistic regression model that was developed in

our study can help determine the etiology of pediatric

patients presenting with a fractured femur. Although

further studies will be necessary to validate the rule

prospectively, we believe the rule is a good common

sense approach to a young patient with a femur fracture.

We believe this method will help all clinicians determine

whether child abuse occurred and thus enhance their

approach to management.

Acknowledgments We thank Dr Cindy Christian, and the Department of Pediatrics at the Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia. In

addition, we acknowledge the SCAN team and the Department of

Emergency Medicine and Trauma at the Childrens Hospital of

Philadelphia.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

1. Anglen JO, Choi L. Treatment options in pediatric femoral shaft

fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:724733.

2. Arkader A, Friedman JE, Warner WC Jr, Wells L. Complete

distal femoral metaphyseal fractures: a harbinger of child abuse

before walking age. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:751753.

3. Caviglia H, Garrido CP, Palazzi FF, Meana NV. Pediatric fractures of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:4956.

4. Coffey C, Haley K, Hayes J, Groner JI. The risk of child abuse in

infants and toddlers with lower extremity injuries. J Pediatr Surg.

2005;40:120123.

5. Flynn JM, Schwend RM. Management of pediatric femoral shaft

fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:347359.

6. Fong CM, Cheung HM, Lau PY. Fractures associated with nonaccidental injuryan orthopaedic perspective in a local regional

hospital. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:445451.

7. Green M, Haggerty RJ. Physically Abused Children. Philadelphia

PA: WB Saunders; 1968:285289.

8. Greene WB. Displaced fractures of the femoral shaft in children.

Unique features and therapeutic options. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

1998;353:8696.

9. Gross RH, Stranger M. Causative factors responsible for femoral

fractures in infants and young children. J Pediatr Orthop.

1983;3:341343.

10. Hsieh FY, Bloch DA, Larsen MD. A simple method of sample

size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Stat Med.

1998;17:16231634.

11. Jones JC, Feldman KW, Bruckner JD. Child abuse in infants with

proximal physeal injuries of the femur. Pediatr Emerg Care.

2004;20:157161.

123

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research1

12. King J, Diefendorf D, Apthorp J, Negrete VF, Carlson M.

Analysis of 429 fractures in 189 battered children. J Pediatr

Orthop. 1988;8:585589

13. Kocher MS, Kasser JR. Orthopaedic aspects of child abuse. J Am

Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:1020.

14. Kowal-Vern A, Paxton TP, Ros SP, Lietz H, Fitzgerald M,

Gamelli RL. Fractures in the under-3-year-old age cohort. Clin

Pediatr (Phila). 1992;31:653659.

15. Lane WG, Dubowitz H. What factors affect the identification and

reporting of child abuse-related fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res.

2007;461:219225.

16. Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical

abuse. JAMA. 2002;288:16031609.

17. Leventhal JM, Thomas SA, Rosenfield NS, Markowitz RI.

Fractures in young children. Distinguishing child abuse from

unintentional injuries. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:8792.

18. Loder RT, Bookout C. Fracture patterns in battered children.

J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5:428433.

19. Loder RT, Feinberg JR. Orthopaedic injuries in children with

nonaccidental trauma: demographics and incidence from the 2000

kids inpatient database. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:421426.

20. Loder RT, ODonnell PW, Feinberg JR. Epidemiology and

mechanisms of femur fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop.

2006;26:561566.

21. Lynch JM, Gardner MJ, Gains B. Hemodynamic significance of

pediatric femur fractures. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:13581361.

22. McKinney A, Lane G, Hickey F. Detection of non-accidental

injuries presenting at emergency departments. Emerg Med J.

2004;21:562564.

23. McMahon P, Grossman W, Gaffney M, Stanitski C. Soft-tissue

injury as an indication of child abuse. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

1995;77:11791183.

24. Nafei A, Teichert G, Mikkelsen SS, Hvid I. Femoral shaft fractures in children: an epidemiological study in a Danish urban

population, 197786. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:499502.

25. OConnor-Read L, Teh J, Willett K. Radiographic evidence to

help predict the mechanism of injury of pediatric spiral fractures

in nonaccidental injury. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:754757.

26. Oral R, Blum KL, Johnson C. Fractures in young children: are

physicians in the emergency department and orthopedic clinics

adequately screening for possible abuse? Pediatr Emerg Care.

2003;19:148153.

27. Pierce MC, Bertocci GE, Janosky JE, Aguel F, Deemer E,

Moreland M, Boal DK, Garcia S, Herr S, Zuckerbraun N,

Vogeley E. Femur fractures resulting from stair falls among children: an injury plausibility model. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1712

1722.

28. Rex C, Kay PR. Features of femoral fractures in nonaccidental

injury. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:411413.

29. Scherl SA, Miller L, Lively N, Russinoff S, Sullivan CM,

Tornetta P 3rd. Accidental and nonaccidental femur fractures in

children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:96105.

30. Schwend RM, Werth C, Johnston A. Femur shaft fractures in

toddlers and young children: rarely from child abuse. J Pediatr

Orthop. 2000;20:475481.

31. Shaw BA, Murphy KM, Shaw A, Oppenheim WL, Myracle MR.

Humerus shaft fractures in young children: accident or abuse?

J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:293297.

32. Sidebotham PD, Pearce AV. Audit of child protection procedures

in accident and emergency department to identify children at risk

of abuse. BMJ. 1997;315:855856.

33. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of fractures in accidental and non-accidental injury in children: a comparative study.

Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:100102.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Traumatic Fracture of The Pediatric Cervical SpineDokumen11 halamanTraumatic Fracture of The Pediatric Cervical SpineVotey CHBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6Dokumen9 halamanPediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6bocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Passaretti 2017Dokumen8 halamanPassaretti 2017reginapriscillaBelum ada peringkat

- Mortensen 2020Dokumen9 halamanMortensen 2020sajith4457Belum ada peringkat

- Kana Afi Nabila-Jurnal 1 MataDokumen11 halamanKana Afi Nabila-Jurnal 1 MataKanafie El NBilaBelum ada peringkat

- The Added Value of A Second Read by Pediatric Radiologists For OutsideDokumen7 halamanThe Added Value of A Second Read by Pediatric Radiologists For OutsideSkander GharbiBelum ada peringkat

- Development of Guidelines For Skeletal Survey in Young Children With FracturesDokumen11 halamanDevelopment of Guidelines For Skeletal Survey in Young Children With FracturesIlta Nunik AyuningtyasBelum ada peringkat

- BMJ f7095Dokumen9 halamanBMJ f7095Luis Gerardo Pérez CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Femur Fractures in Infants and Young ChildrenDokumen3 halamanFemur Fractures in Infants and Young Childrenbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnostic Yield of Computed Tomography Scan For Pediatric Hearing Loss A Systematic ReviewDokumen22 halamanDiagnostic Yield of Computed Tomography Scan For Pediatric Hearing Loss A Systematic ReviewadriricaldeBelum ada peringkat

- Osteoporosis Draft Evidence ReviewDokumen397 halamanOsteoporosis Draft Evidence ReviewChon ChiBelum ada peringkat

- Sciencedirect: Prehospital Care and Transportation of Pediatric Trauma PatientsDokumen7 halamanSciencedirect: Prehospital Care and Transportation of Pediatric Trauma PatientsJhon GariboBelum ada peringkat

- Papola 2018Dokumen56 halamanPapola 2018sajith4457Belum ada peringkat

- Screening To Prevent Osteoporotic Fractures AnDokumen448 halamanScreening To Prevent Osteoporotic Fractures AnMayday FinishaBelum ada peringkat

- Concussion Management in Soccer 04Dokumen5 halamanConcussion Management in Soccer 04Luvanor SantanaBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal 6Dokumen17 halamanJurnal 6Dhiny RatuBelum ada peringkat

- 2-Ped. Clinics of North America-April 2009, Vol.56, Issues 2, Child Abuse and Neglect - Advancements and Challenges in The 21st CenturyDokumen122 halaman2-Ped. Clinics of North America-April 2009, Vol.56, Issues 2, Child Abuse and Neglect - Advancements and Challenges in The 21st CenturyDina HottestwopiemBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma, Volume 2: Medical Mimics Pocket AtlasDari EverandPediatric Abusive Head Trauma, Volume 2: Medical Mimics Pocket AtlasBelum ada peringkat

- Amel 12Dokumen9 halamanAmel 12melon segerBelum ada peringkat

- The Pediatric "Floating Knee" Injury: A State-of-the-Art Multicenter StudyDokumen7 halamanThe Pediatric "Floating Knee" Injury: A State-of-the-Art Multicenter StudyManiDeep ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- Azad 2019Dokumen7 halamanAzad 2019Eka BagaskaraBelum ada peringkat

- Epidemiology of Lawnmower-Related Injuries in Children: A 10-Year ReviewDokumen6 halamanEpidemiology of Lawnmower-Related Injuries in Children: A 10-Year ReviewLalzio CalmalzioBelum ada peringkat

- Facial Fractures in Patients With Firearm Injuries: Profile and OutcomesDokumen7 halamanFacial Fractures in Patients With Firearm Injuries: Profile and OutcomesMaria Alejandra AtencioBelum ada peringkat

- Child Abuse Inventory at Emergency Rooms: CHAIN-ER Rationale and DesignDokumen7 halamanChild Abuse Inventory at Emergency Rooms: CHAIN-ER Rationale and DesignIsnaBelum ada peringkat

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.03.021Dokumen23 halamanAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.03.021AndikaBelum ada peringkat

- Controversies in Pediatric AppendicitisDari EverandControversies in Pediatric AppendicitisCatherine J. HunterBelum ada peringkat

- Complex Trauma Screener For PediatriciansDokumen7 halamanComplex Trauma Screener For Pediatriciansapi-434196971Belum ada peringkat

- Child Abuse & NeglectDokumen10 halamanChild Abuse & NeglectStéphanie DWBelum ada peringkat

- Knowledge On Complications of Immobility Among The Immobilized Patients in Selected Wards at Selected HospitalDokumen3 halamanKnowledge On Complications of Immobility Among The Immobilized Patients in Selected Wards at Selected HospitalIOSRjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: Clinical Principles and ApplicationsDari EverandEmery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: Clinical Principles and ApplicationsReed E. PyeritzBelum ada peringkat

- 77d8 PDFDokumen7 halaman77d8 PDFRosyid PrasetyoBelum ada peringkat

- Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: FoundationsDari EverandEmery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics and Genomics: FoundationsReed E. PyeritzBelum ada peringkat

- Daño InglesDokumen9 halamanDaño InglesbrukillmannBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures: Treatment Strategies According To Age - 13 Years of Experience in One Medical CenterDokumen6 halamanPediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures: Treatment Strategies According To Age - 13 Years of Experience in One Medical CenterAnonymous 1EQutBBelum ada peringkat

- glx190 PDFDokumen9 halamanglx190 PDFLegowo SatrioBelum ada peringkat

- Vertebral Fracture Risk (VFR) Score For Fracture Prediction in Postmenopausal WomenDokumen11 halamanVertebral Fracture Risk (VFR) Score For Fracture Prediction in Postmenopausal WomenAdhiatma DotBelum ada peringkat

- Imaging in Pediatric OncologyDari EverandImaging in Pediatric OncologyStephan D. VossBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer Psico1Dokumen14 halamanContentServer Psico1Luis.fernando. GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Child Sexual Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy DirectionsDari EverandChild Sexual Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy DirectionsBelum ada peringkat

- Tanto El Inhalador de Aerosol Presurizado Como Con El Nebulizador Alrededor de Un 10Dokumen11 halamanTanto El Inhalador de Aerosol Presurizado Como Con El Nebulizador Alrededor de Un 10Jany UllauriBelum ada peringkat

- CiTBI Paper - Stephen RohlDokumen13 halamanCiTBI Paper - Stephen RohlAnonymous zJGsK3RBelum ada peringkat

- 2017 - Alomari Et AlDokumen18 halaman2017 - Alomari Et AlazeemathmariyamBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S1477513123004217 MainDokumen5 halaman1 s2.0 S1477513123004217 MainScanMe Labs KlinikBelum ada peringkat

- Office Based Anesthesia Complications: Prevention, Recognition and ManagementDari EverandOffice Based Anesthesia Complications: Prevention, Recognition and ManagementGary F. BoulouxBelum ada peringkat

- The Saudi Publics Knowledge Level of Spinal Injury A Novel Risk Prediction Scoring SystemDokumen6 halamanThe Saudi Publics Knowledge Level of Spinal Injury A Novel Risk Prediction Scoring SystemResearch and Development DepartmentBelum ada peringkat

- Brain Tumors in ChildrenDari EverandBrain Tumors in ChildrenAmar GajjarBelum ada peringkat

- Anesthetic Management for the Pediatric Airway: Advanced Approaches and TechniquesDari EverandAnesthetic Management for the Pediatric Airway: Advanced Approaches and TechniquesDiego PreciadoBelum ada peringkat

- Life Histories of Genetic Disease: Patterns and Prevention in Postwar Medical GeneticsDari EverandLife Histories of Genetic Disease: Patterns and Prevention in Postwar Medical GeneticsBelum ada peringkat

- Nonaccidental Pediatric Trauma - Which Traditional Clues Predict AbuseDokumen5 halamanNonaccidental Pediatric Trauma - Which Traditional Clues Predict AbuseolivierdomengeBelum ada peringkat

- Race and Insurance Status As Risk Factors For Trauma MortalityDokumen5 halamanRace and Insurance Status As Risk Factors For Trauma MortalitySam CholkeBelum ada peringkat

- Safe Pediatric AnesthesiaDokumen24 halamanSafe Pediatric AnesthesiamdBelum ada peringkat

- Paediatric Neck MassesDokumen7 halamanPaediatric Neck MassesGiovanni HenryBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Factors For Acute Compartment Syndrome of The Leg Associated With Tibial Diaphyseal Fractures in AdultsDokumen8 halamanRisk Factors For Acute Compartment Syndrome of The Leg Associated With Tibial Diaphyseal Fractures in AdultsZakii MuhammadBelum ada peringkat

- Drenaje Presacro Injurias de RectoDokumen9 halamanDrenaje Presacro Injurias de RectoDeyvit ManzanoBelum ada peringkat

- A JR CCM 183121715Dokumen8 halamanA JR CCM 183121715TriponiaBelum ada peringkat

- Frailty and The Prediction of Negative Health OutcomesDokumen17 halamanFrailty and The Prediction of Negative Health OutcomesSusan RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Artikel 2Dokumen20 halamanArtikel 2rimafitrianiBelum ada peringkat

- A Comparison of Obstetric Maneuvers For The Acute Management of Shoulder DystociaDokumen7 halamanA Comparison of Obstetric Maneuvers For The Acute Management of Shoulder DystociaNellyn Angela HalimBelum ada peringkat

- CRITIQUE REVIEW (New)Dokumen6 halamanCRITIQUE REVIEW (New)Anita De GuzmanBelum ada peringkat

- Journal of Dental Research: Unilateral Posterior Crossbite Is Not Associated With TMJ Clicking in Young AdolescentsDokumen6 halamanJournal of Dental Research: Unilateral Posterior Crossbite Is Not Associated With TMJ Clicking in Young AdolescentsJavangula Tripura PavitraBelum ada peringkat

- 03 - Energy BalanceDokumen8 halaman03 - Energy Balancebocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- 17 - Enhanced Recovery PrinciplesDokumen7 halaman17 - Enhanced Recovery Principlesbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- 03 - Nutritional Screening and Assessment PDFDokumen8 halaman03 - Nutritional Screening and Assessment PDFbocah_britpop100% (1)

- 17 - The Traumatized PatientDokumen7 halaman17 - The Traumatized Patientbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- 08 - Indications, Contraindications, Complications and Monitoring of enDokumen13 halaman08 - Indications, Contraindications, Complications and Monitoring of enbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- ACS SabistonDokumen10 halamanACS Sabistonbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- 08 - Oral and Sip FeedingDokumen11 halaman08 - Oral and Sip Feedingbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Tuesday, March 09 2015: Team in ChargeDokumen2 halamanTuesday, March 09 2015: Team in Chargebocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Intraabdominal Pressure MonitoringDokumen10 halamanIntraabdominal Pressure Monitoringbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- IAH ACS Medical Management 2014Dokumen1 halamanIAH ACS Medical Management 2014bocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- IAH ACS Management 2014Dokumen1 halamanIAH ACS Management 2014bocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Case Disc RadioDokumen29 halamanCase Disc Radiobocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- University of Colorado NICHE Practice Survey SummaryDokumen48 halamanUniversity of Colorado NICHE Practice Survey Summarybocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Tuesday, March 09 2015: Team in ChargeDokumen7 halamanTuesday, March 09 2015: Team in Chargebocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Art 3A10.1007 2Fs11832 014 0590 3Dokumen7 halamanArt 3A10.1007 2Fs11832 014 0590 3bocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Femur Fractures in Infants and Young ChildrenDokumen3 halamanFemur Fractures in Infants and Young Childrenbocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Spectrum of Operative Childhood Intra-Articular Shoulder PathologyDokumen4 halamanSpectrum of Operative Childhood Intra-Articular Shoulder Pathologybocah_britpopBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-Hospital Assessment Sheet: Triage ScoreDokumen2 halamanPre-Hospital Assessment Sheet: Triage Scoreratna purwitasariBelum ada peringkat

- FASENRA - PFS To Pen Communication Downloadable PDFDokumen2 halamanFASENRA - PFS To Pen Communication Downloadable PDFBrîndușa PetruțescuBelum ada peringkat

- EndosDokumen38 halamanEndosYogi AnjasmaraBelum ada peringkat

- Icf Pri P2 414 PDFDokumen17 halamanIcf Pri P2 414 PDFMichael Forest-dBelum ada peringkat

- Rabies ScribdDokumen78 halamanRabies Scribdbryfar100% (1)

- MCQ-Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDokumen3 halamanMCQ-Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseMittulBelum ada peringkat

- Howtousea Nebulizer in Pediatric ClientsDokumen11 halamanHowtousea Nebulizer in Pediatric ClientsAngelina Nicole G. TungolBelum ada peringkat

- Drug Study MetoclopramideDokumen2 halamanDrug Study MetoclopramidePrince Rupee Gonzales100% (2)

- Case 1 Doc GonsalvesDokumen7 halamanCase 1 Doc GonsalvesMonique Angela Turingan GanganBelum ada peringkat

- Silver Book Part A Medication Management ID3104Dokumen7 halamanSilver Book Part A Medication Management ID3104Anton BalansagBelum ada peringkat

- Rheumatic FeverDokumen61 halamanRheumatic FeverCostea CosteaBelum ada peringkat

- Resume For LPNDokumen8 halamanResume For LPNafllwwtjo100% (1)

- Using The PICOTS Framework To Strengthen Evidence Gathered in Clinical Trials - Guidance From The AHRQ's Evidence Based Practice Centers ProgramDokumen1 halamanUsing The PICOTS Framework To Strengthen Evidence Gathered in Clinical Trials - Guidance From The AHRQ's Evidence Based Practice Centers ProgramAdhyt PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Care PT For Covid 19 PatientsDokumen17 halamanAcute Care PT For Covid 19 PatientsSelvi SoundararajanBelum ada peringkat

- Blood Admin FormDokumen8 halamanBlood Admin Formapi-276837530Belum ada peringkat

- What Is Multiple MyelomaDokumen2 halamanWhat Is Multiple MyelomaRegine Garcia Lagazo100% (1)

- Outline 2Dokumen8 halamanOutline 2api-432489466Belum ada peringkat

- Things To Remember: - After EarthquakeDokumen20 halamanThings To Remember: - After Earthquakeangelyca delgadoBelum ada peringkat

- Vascular Surgery MiamiDokumen5 halamanVascular Surgery MiamiwilberespinosarnBelum ada peringkat

- Chorionic Bump in First-Trimester Sonography: SciencedirectDokumen6 halamanChorionic Bump in First-Trimester Sonography: SciencedirectEdward EdwardBelum ada peringkat

- Matas RationalizationDokumen12 halamanMatas RationalizationCerezo, Cherrieus Ann C.Belum ada peringkat

- Literature Review Cesarean SectionDokumen5 halamanLiterature Review Cesarean Sectionafmzkbysdbblih100% (2)

- Classified AdsDokumen3 halamanClassified Adsapi-312735990Belum ada peringkat

- RecentresumeDokumen2 halamanRecentresumeapi-437056180Belum ada peringkat

- LAP DirectoryDokumen36 halamanLAP Directorydolly wattaBelum ada peringkat

- Visudyne Verteforpin Inj FDADokumen13 halamanVisudyne Verteforpin Inj FDAUpik MoritaBelum ada peringkat

- Heri Fadjari - Case StudiesDokumen15 halamanHeri Fadjari - Case StudiesHartiniBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Jigar PatelDokumen6 halamanDr. Jigar PatelJigar PatelBelum ada peringkat

- Practice AMCDokumen23 halamanPractice AMCPraveen AggarwalBelum ada peringkat

- Rheumatology Quiz.8Dokumen1 halamanRheumatology Quiz.8Ali salimBelum ada peringkat