BULMAN Characterological Versus Behavioral Self-Blame Inquiries Into Depression and Rape PDF

Diunggah oleh

daerrreDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

BULMAN Characterological Versus Behavioral Self-Blame Inquiries Into Depression and Rape PDF

Diunggah oleh

daerrreHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

1979, Vol. 37, No. 10, 1798-1809

Characterological Versus Behavioral Self-Blame: Inquiries Into

Depression and Rape

Ronnie Janoff-Bulman

University of MassachusettsAmherst

Two types of self-blamebehavioral and characterologicalare distinguished.

Behavioral self-blame is control related, involves attributions to a modifiable

source (one's behavior), and is associated with a belief in the future avoidability of a negative outcome. Characterological self-blame is esteem related,

involves attributions to a relatively nonmodifiable source (one's character), and

is associated with a belief in personal deservingness for past negative outcomes.

Two studies are reported that bear on this self-blame distinction. In the first

study, it was found that depressed female college students engaged in more

characterological self-blame than nondepressed female college students, whereas

behavioral self-blame did not differ between the two groups; the depressed

population was also characterized by greater attributions to chance and decreased beliefs in personal control. Characterological self-blame is proposed as

a possible solution to the "paradox in depression." In a second study, rape

crisis centers were surveyed. Behavioral self-blame, and not characterological

self-blame, emerged as the most common response of rape victims to their

victimization, suggesting the victim's desire to maintain a belief in control,

particularly the belief in the future avoidability of rape. Implications of this

self-blame distinction and potential directions for future research are discussed.

In a study by Bulman and Wortman

(1977) on the relationship between blame

attributions and coping, self-blame emerged

as a predictor of good coping among paralyzed victims of freak accidents. A conclusion

that is consistent with these resultsthat

self-blame is a positive psychological mechanismderives primarily from the implications of this attribution for a belief in personal control over one's outcomes. The advantages of perceived control have been repeatedly demonstrated in social psychological

experiments (see, e.g., Bowers, 1968; Glass &

Singer, 1972; Langer & Rodin, 1976; Schulz,

1976); Walster's (1966) formulation of observers' reactions to victims and Kelley's

(1971) view of attributional processes "as a

The author thanks Philip Brickman, Irene Frieze,

and Camille Wortman for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Requests for reprints should be sent to Ronnie

Janoff-Bulman, University of Massachusetts, Department of Psychology, Amherst, Massachusetts

01003.

means of encouraging and maintaining [his]

effective exercise of control in the world"

(p. 22) are also based upon a recognition of

the significance of perceived control. The

tenuous link between control and self-blame

becomes comprehensible as one realizes that

in order to maximize a belief in control when

attributing blame to particular factors, one's

choice is influenced by the perceived modifiability of the potential factor(s). As Medea

and Thompson (1974) write in the case of

rape, "If the woman can believe that somehow she got herself into the situation, if she

can make herself responsible for it, then she's

established some sort of control over rape.

It wasn't someone arbitrarily smashing into

her life and wreaking havoc" (p. 105).

Unfortunately, this adaptive, control-oriented view of self-blame too easily ignores

the more popular conception of the phenomenon, by which self-blame is regarded as maladaptive, a correlate of depression, and a

reflection of psychological problems. Thus

Beck (1967), writing about depressed pa-

Copyright 1979 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-3514/79/3710-1798$00.7S

1798

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

tients, states, "Another symptom, self-blame,

expresses the patient's notion of causality.

He is prone to hold himself responsible for

any difficulties or problems that he encounters" (p. 21). Self-blame as a maladaptive

psychological mechanism is generally related

to harsh self-criticism and low evaluations of

one's worth.

Two Types oj Self-Blame

Recognizing that self-blame may be both

adaptive and maladaptive is a first step towards the conclusion that there are two

different types of self-blame, one representing

an adaptive, control-oriented response, the

other a maladaptive, self-deprecating response. The primary distinction between

these two self-attributions is the nature of

the focus of blame, for it is proposed that

the control related self-blame focuses on one's

own behavior, whereas the esteem related

self-blame focuses on one's character, an

overall view of the kind of people individuals

perceive themselves to be. In other words,

individuals can blame themselves for having

engaged in (or having failed to engage in) a

particular activity, thereby attributing blame

to past behaviors; or individuals can blame

themselves for the kind of people they are,

thereby faulting their character. To facilitate

discussion of these two self-attributional

strategies, the esteem related blame will be

labeled "characterological" self-blame and

the control related type, "behavioral" selfblame. In the case of rape, for example, a

woman can blame herself for having walked

down a street alone at night or for having

let a particular man into her apartment (behavioral blame), or she can blame herself for

being "too trusting and unable to say no"

or a "careless person who is unable to stay

out of trouble." This behavioral-characterological distinction parallels findings in the

area of the just world theory. In their recent

review, Lerner and Miller (1978) state

that innocent victims who cannot be characterologically blamed (i.e., derogated) by

virtue of their reputedly good character are

instead blamed for some behavior in which

they engaged (i.e., behavioral blame).

While this distinction between charactero-

1799

logical and behavioral self-blame appears

related to the state-trait distinction in clinical psychology (see, e.g., Spielberger, 1972),

it more specifically corresponds to the distinctions drawn by Weiner and his colleagues

(Weiner et al., 1971) in their scheme of

attributions in the area of achievement. In

attributing failure to oneself (internal attribution), one can point to his/her own lack

of ability or effort, attributions that have

very different implications for perceived control. Individuals who make an attribution

to poor ability believe that there is little

they can do to control the situation and succeed, for ability is stable and relatively unchangeable. Effort attributions, on the other

hand, will lead one to believe that as long

as he/she tries harder, he/she will be able to

control outcomes in a positive manner (see

Dweck, 1975). Similarly, characterological

self-blame corresponds to an ability attribution, and behavioral self-blame corresponds

to an effort attribution, having very different

implications for perceived personal control.

While the dimension used by Weiner and his

colleagues to distinguish between ability and

effort is that of stability (stable-unstable),

the differences between the attributions may

also be captured through the use of a controllability dimension (cf. Elig & Frieze,

1975; Weiner, 1974). The primary distinction to be drawn between behavioral and

characterological self-blame is the perceived

controllability (i.e., modifiability through

one's own efforts) of the factor(s) blamed.

In a recent reformulation of learned helplessness, Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale

(1978) have posited a third dimension of attributionsglobal-specificthat is important

to specify in determining subsequent perceived helplessness. While this global-specific

dimension characterizes one of the differences

to be noted between characterological and

behavioral self-blame, it is proposed that the

dimension of significance distinguishing these

two types of self-blame is perceived controllability, and the globalspecific and

stable-unstable dimensions are important because of their contribution to perceived control. Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale

(1978), however, note that the dimension of

"controllability is logically orthogonal to the

1800

RONNIE JANOFF-BULMAN

Internal X Global X Stable dimensions . . ."

(p. 62). The position presented here is consistent with a comment by Wortman and

Dintzer (1978) in their recent reaction to

the learned helplessness reformulation. They

state, "We feel that assessments of the controllability of the causal factor may be of

the utmost importance in predicting the nature and magnitude of subsequent deficits"

(p. 82).

In a discussion of self-blame by Abramson,

Seligman, and Teasdale (1978) these authors

state that self-blame in helplessness and depression follows from the "attribution of

failure to factors that are controllable" (p.

62). The self-blame they are dealing with is

that which is consistent with "self-esteem

deficits" and "self-criticism" and thus parallels characterological self-blame. The authors

do not recognize a second type of self-blame,

behavioral self-blame, which according to

the present analysis is the type of self-blame

following from attributions to controllable

factors. Contrary to the assertions of Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale, it is proposed

that characterological self-blame follows from

attributions to uncontrollable factors.

A further distinction between behavioral

and characterological self-blame lies in the

time orientation of the attributor. It is proposed that in blaming one's behavior, an

individual is concerned with the future, particularly the future avoidability of the negative outcome. This concern for future avoidability is consistent with the control-motivated basis for behavioral self-blame. The

future-oriented concerns of behavioral selfblamers need not focus exclusively on the

future avoidability of the negative outcome

for which the attributor is blaming him/herself; rather, behavioral self-blame may promote a general belief in one's ability to avoid

negative outcomes and to effect positive outcomes in the future. Thus, the paralyzed

victims in the Bulman and Wortman (1977)

study were apt to be better copers if they

blamed themselves, but self-blame was more

likely to be in the service of a general belief

in future control (e.g., I'll be able to improve my physical condition through physical therapy), rather than a more specific

belief in the future avoidability of their own

paralysis, which was medically regarded as

irreversible in all cases.

In blaming himself or herself characterologically, the individual is not concerned

with control in the future, but rather with

the past, particularly deservingness for past

outcomes. Individuals who engage in behavioral self-blame are apt to have an eye

towards the future and what they can do

to avoid a recurrence of the negative outcome (or the occurrence of negative outcomes in general). Individuals who engage

in characterological self-blame are apt to

focus more on the past and what it was about

them that rendered them deserving of the

negative outcome for which they are blaming

themselves.1 Perceived avoidability and behavioral self-blame are thus assumed to be

part of the same blame cluster, whereas characterological self-blame and feelings of deservingness are representative of another

blame cluster.

Selj-Blame and Depression;

Toward the Resolution of a Paradox

Distinguishing between characterological

and behavioral self-blame may be a first step

toward resolving the "paradox in depression"

recently recognized and discussed by Abramson and Sackeim (1977). According to these

authors, there are two symptom clusters of

depression, one represented by hopelessness,

powerlessness, and futility, the other by selfblame, self-deprecation, and guilt. Abramson

and Sackeim discuss two prominent theories

of depression that are based on cognitions

of hopelessness and self-blame. Seligman's

(1975) theory of learned helplessness suggests that depression results from a belief

in the uncontrollability of outcomes. According to Beck's (1967) theory of depression,

the depressed individual blames him/herself

for negative outcomes, particularly personal

failures. It is the conjunction of these two

models that accounts for the paradox. That

1

These distinctions are consistent with a recent

analysis of responsibility by Harvey and Rule

(1978), in which causal responsibility and deservingness are regarded as conceptually distinct aspects

of responsibility.

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

is, how can individuals blame themselves

for outcomes over which they feel they have

had no control? How can an individual feel

both helpless and self-blaming? Abramson

and Sackeim discuss several possible resolutions to this paradox but remain dissatisfied

with the alternatives presented to date. However, a recognition of self-blame, not as a

unitary phenomenon, but rather as a label

for two very different self-attributional strategies, may inform and resolve the apparent

paradox in depression.

One reason why a resolution to the depression paradox has not been forthcoming

is suggested by Abramson, Seligman, and

Teasdale's

(1978) assertion (presented

above) that self-blame follows from attributions to controllable factors. In assuming that

self-blame naturally involves blaming controllable factors, the possibility that individuals can simultaenously feel they do not have

control and blame themselves is foreclosed.

Instead, if we recognize the distinction between behavioral and characterological selfblame, then the paradox begins to disappear.

Essential to an understanding of this assertion is the proposition that in blaming himself or herself for the kind of person he/she is,

the individual is not necessarily placing

blame for an event regarded as personally

controllable. A person can believe that he/she

deserves what happened and is therefore "responsible" for it (see Harvey & Rule, 1978),

without believing that he/she is capable of

altering the outcome in the past, present, or

future.

In the case of personal failures, the charterological blamers will point to deficits in

themselves that are believed to account for

these failures. The deficits are likely to lie

in the realm of characteristics that generally

define them, characteristics that are relatively nonmodifiable, stable, and global.

Thus, in achievement tasks, an ability attribution would represent a characterological

self-blaming strategy. In the case of selfblame for failures that are further removed

from the individual, represented by the "delusions of depressives" who blame themselves

for the "violence and suffering in the world"

(see Beck, 1967), the individuals appear to

regard themselves as being punished for who

1801

or what they are. In this case, rather than

perceive themselves as responding, active organisms, depressed individuals seem to perceive themselves as passive stimuli. They do

not believe they actively bring about outcomes that remain under their control.

Rather, negative outcomes occur in reaction

to them by other people and the world at

large. In sum, self-blame by depressives is

proposed as characterological in nature. Since

characterological self-blame and feelings of

helplessness are not logically inconsistent,

their conjunction in depressed individuals

should not be regarded as paradoxical.

Self-Blame Among Rape Victims

The association between self-blame and

depression is probably well recognized and

accepted within this culture. While the association between self-blame and rape is probably not as strong, the more or less popular

image of the self-blaming rape victim may

be more accurate than many would like to

believe. The pervasiveness of self-blame has

been well documented in literature on rape

(see, e.g., Burgess & Holmstrom, 1974a,

1974b, 1976; Griffin, 1971; Hursch, 1977;

Weis & Weis, 197S; Bryant & Cirel, Note 1).

Although fear (of injury, death, and the

rapist) is the primary reaction to rape, selfblame may be second only to fear in frequency of occurrence; perhaps surprisingly,

it is far more common than anger.

In considering the few existing facts on

victim precipitation in the crime of rape,

however, it becomes obvious that the victims' self-attributional strategies (i.e., selfblame) do not reflect an accurate appraisal

of the woman's causal role in the assault.

The National Commission on the Causes and

Prevention of Violence (1969) concluded that

only 4.4% of all rapes are precipitated by

the victim. Although a higher figure, 19%,

has been proposed by Amir (1971), he used a

considerably broader definition in establishing his criteria for victim precipitation. Thus,

criteria such as "risky situations marred with

sexually" were used, affording the interpreter

of data considerable discretion. In light of

these percentages, the pervasiveness of selfblame becomes a puzzling phenomenon.

1802

RONNIE JANOFF-BULMAN

An attempt to account for the pervasiveness of such feelings has involved the proposition that women have been socialized to

accept blame for their own victimization. As

Brownmiller (197S) suggests, women are

conditioned to a female victim mentality.

Brownmiller discusses the psychologies of

Deutsch and Horney and concludes that

masochism is a female trait, one that has

been socialized by men. Similarly, Burgess

and Holmstrom (1974a) contend that women

are socialized to the attitude of "blaming

the victim," a perspective shared by Bryant

and Cirel (Note 1). While there is no doubt

much truth to this socialization hypothesis,

it may paint a very incomplete picture of

the factor(s) responsible for self-blame in

women and the rape victim in particular.

It fits nicely with a portrait of women as

helpless and masochistic and may unwittingly perpetuate a view of women too consistent with the role of rape victim. In particular, this view entirely overlooks the possibility that self-blame by victims of rape may

represent an adaptive response, an attempt

to reestablish control following the trauma

of rape.

A common reaction to rape is the feeling

of a loss of control over one's life (Bard &

Ellison, 1974; Bryant & Cirel, Note 1). The

woman does not feel sure of herself and questions her self-determination. She needs to

feel a sense of control (Hilberman, 1976),

for she feels extremely vulnerable and particularly fears the rapist and a recurrence of

rape. In blaming herself, perhaps the rape

victim is engaging in a type of self-blame

that maximizes a belief in control; that is,

perhaps rape victims engage in behavioral

self-blame rather than characterological selfblame. Whereas the latter type of blame

would provide some support for a view of

women as helpless and masochistic, the former would foster a different image of the

rape victim and her reactions, that of an individual reacting in an adaptive manner

to her recent loss of control.

If the rape victim engages in behavioral

self-blame and attributes her victimization

to a modifiable behavior (e.g., I should not

have walked alone, I should have locked the

windows), she is likely to maintain a belief

in the future avoidability of a similar misfortune, while simultaneously maintaining a

belief in personal control over important life

outcomes. If, on the other hand, the rape

victim blames herself characterologically, attributing the victimization to more or less

unchangeable factors (e.g., I'm a weak person

and can't say so, I'm the type of person who

attracts rapists), she will presumably be considerably less likely to believe that she is

capable of alleviating her vulnerability in the

future and may begin to perceive herself as

a chronic victim.

Two studies were conducted in order to

test the usefulness of the distinction between behavioral and characterological selfblame in the areas of depression and rape.

Study 1 was designed to determine whether

characterological self-blame is a distinguishing characteristic of depressed individuals

and whether it co-occurs with decreased beliefs in personal control among female college students. Study 2 involved surveying

rape crisis centers across the country in order

to determine which type of self-blamebehavioral or characterologicalmore accurately characterizes the reactions of rape victims served by these centers.

Study 1: Depression

Method

Subjects. Subjects were 129 undergraduate women at a large state university who were volunteers drawn from a number of undergraduate psychology courses. Each received one experimental

credit for her participation. Responses from 9 of

the subjects lacked much data, and these were eliminated from the analyses, leaving the responses of

120 subjects.

Procedure, Data - were collected during group

sessions that generally ranged from 10 to IS students. Subjects were told that we were interested in

the relationship between personality variables and

artistic taste, and that there would be three parts

2

These data were collected by Laurie Gunsolley

for her senior honors thesis, which was designed

and completed under the direction of the author.

While Gunsolley was particularly interested in selfesteem, the data have been reanalyzed for this

presentation, using the responses to the Zung SelfRating Depression Scale (1965) as the basis for

distinguishing between the two groups of interest.

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

to the study: completing personality scales, viewing and rating a series of art slides, and reacting

to several "real-life" types of situations. The subjects were asked to complete three personality scales.

The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung, 1965)

was used to measure depression.3 In addition, subjects completed the Janis-Field Feelings of Inadequacy Scale (Eagly, 1967), a self-esteem measure,

and the Rotter Internal-External Locus of Control

Scale (Rotter, 1966). Having completed these, the

subjects were then asked to rate seven art slides on

"aesthetic appeal." An overhead projector was used

to show the slides, and ratings were made on 5point scales. These artistic ratings not only provided a "cover" for the study but, more important,

served as a distraction between the first (personality scales) and third (self-blame measures) parts

of the experiment.

In the third phase of the study, subjects were

asked to read four scenarios and to imagine that

the various situations described had actually been

experienced by them; that is, they were told to

react to the scenarios given that they were the

target people presented. In each situation the outcome was negative and the role of the target person was intentionally ambiguous. The scenarios involved the following situations: (a) a car driven

by the target person is in an accident on a snowy

winter day; (b) a social invitation by the target

person is rejected (on the basis of false excuses)

by an individual she recently met and regarded as

a friend: (c) an urgent call for a roommate results

in the target person's taking down the wrong number; the roommate is subsequently unable to return

the call successfully; (d) an intense love relationship is ended when the target person's boyfriend

leaves her and immediately gets involved with another woman.

Subjects were asked to respond to five questions

following each scenario; responses were made on

6-point scales with endpoints not at all and completely. Subjects were asked to indicate how much

they blamed themselves, other people, the environment (i.e., impersonal world), and chance, for the

situations described. The question that tapped

characterological self-blame asked, "Given what

happened, how much do you blame yourself for

the kind of person you are (e.g., the kind of person

who is in an accident [Scenario A], the kind of

person who has invitations turned down [Scenario

B], the kind of person who causes inconveniences

for others [Scenario C], the kind of person who is

rejected in relationships [Scenario D])?" The appropriate "kind of person" was included separately

for each scenario, so that for scenario D only "the

kind of person who is rejected in relationships"

was included. Question 3 sought to tap behavioral

self-blame and asked, "Given what happened, how

much do you blame yourself for what you did

(e.g., your driving behavior [Scenario A], how you

acted when you first met the person [Scenario B],

how you acted when taking down the telephone

number [Scenario C], how you acted with your

1803

boyfriend [Scenario D])?" Question 4 asked, "How

much do you think you deserved what happened?"

and Question 5 following each scenario was, "If the

same situation arose in the future, to what extent

do you believe that you could avoid what happened in this case?" All subjects were thoroughly

debriefed upon completion of the session.

Results

Using a median split, subjects were divided

into nondepressed (responses ranged from

6 to 21 on the Zung scale) and depressed

(22 to 45 on the Zung scale) groups.4 On the

Janis-Field Feelings of Inadequacy Scale,

the depressed group scored lower (i.e., had

lower self-esteem) than the nondepressed

group (64.05 vs. 74.97), F(l, 118) = 36.72,

p < .001, and the depressed group was found

to be more external than the nondepressed

group on Rotter's Internal-External Locus

of Control Scale (13.36 vs. 10.57), /?(!, 118)

= 12.32, p< .001.

Parallel attributional and self-blame measures were summed across the four scenarios;

for example, a score for characterological

blame was derived by adding the individual

responses to each of the four questions (one

following each scenario) that asked about

characterological self-blame. In order to

justify adding the four scales, alpha reliability coefficients were calculated for each of

the eight summed scores. Despite the fact

that each was composed of four scores, only

the perceived avoidability measure failed to

reach a reliability of .50. The general self

and other people attributions were less than

.60, and the other five measures had alpha

reliabilities between .62 and .74.5 Each

3

In accordance with work on depression by Bonnie Strickland, a clinical psychologist in the Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, a response category labeled "none

of the time" was added to the Zung Self-Rating

Depression Scale (1965). According to Strickland

(personal communication), this renders the scale

particularly sensitive to depression in a college

population.

4

Male and female college students completed the

same depression scale in a study by Haley and

Strickland (Note 2 ) ; their data had a median of 23.

5

Nunnally (1967) writes that in early work on

"hypothesized measures of a construct", reliabilities

of .50 or .60 are sufficient standards (see p. 226).

1804

RONNIE JANOFF-BULMAN

summed score could range from a total of

0 to 24.

The depressed and nondepressed groups

did not differ in the amount of blame they

attributed to themselves in general, nor did

they differ in the amount of behavioral selfblame reported, F ( l , 118) = 2.47, ns. However, the groups did differ significantly in

the amount of characterological self-blame

reported, with more characterological selfblame reported by the depressed than the

nondepressed group (11.59 vs. 10.03), F(l,

118) =4.33, p < .05. Other differences on

the total scores were found for attributions

to chance; consistent with their greater externality on Rotter's scale, the depressed

group blamed chance more than the nondepressed group (11.38 vs. 9.73), F(l, 118) =

4.54, p < .05. Further, there was a marginally significant difference between the two

groups on the question of how much they

felt they deserved what happened, with the

depressed group reporting greater deservingness than the nondepressed group (8.31 vs.

7.24), F ( l , 118) = 3.68, p = .057.6

A stepwise discriminant analysis was conducted in order to determine the variables

that differentiated best between the two

groups. All blame attribution measures were

entered, with the exception of general selfblame, since characterological and behavioral

self-blame were assumed to be finer distinctions of the general measure. Attributions to

chance emerged as the best discriminator,

F(5, 114) = 4.54, Wilks A. = .963, and characterological self-blame emerged as the next

strongest differentiator, F(5, 114) = 3.29,

Wilks A = .937. These were followed, respectively, by attributions to other people, environment, and behavioral self-blame.

The correlations between deservingness,

perceived avoidability, and the two types of

self-blame were all strong. As an exploratory

tool, an analysis of variance was conducted in

order to further investigate the relationship

between the variables. It should be noted that

the low reliability of the avoidability measure

calls for caution in interpreting the results of

this analysis. Median splits were performed

on the behavioral self-blame and characterological self-blame totals, and deservingness

and avoidability totals were each analyzed

by behavioral (high-low) and characterological (high-low) self-blame. A main effect for

characterological self-blame emerged from the

analysis of deservingness, with less deservingness reported by those who engaged in low

characterological self-blame as compared with

those who engaged in high characterological

self-blame (6.20 vs. 9.26), F(l, 119) = 29.78,

p < .001. On the other hand, a main effect

for behavioral self-blame emerged from the

analysis of perceived future avoidability, with

less perceived future avoidability reported by

those who engaged in low behavioral selfblame as compared with those who engaged in

high behavioral self-blame (11.89 vs. 13.88),

F(l, 118) = 6.85, p < .01.

Discussion

When self-blame was treated as a single

entity (i.e., "self" as one of several possible

factors tapped for blame attributions), no

differences were found between the depressed

and nondepressed students on this variable.

However, when self-blame was divided into

two types of self-attributions, behavioral and

characterological, differences between the

groups emerged. While the depressed and

nondepressed students did not differ in terms

of behavioral self-blame, they did differ significantly in terms of characterological selfblame; that is, the depressed students blamed

themselves more characterologically than did

the nondepressed students.

The suggestion that characterological selfblame follows from attributions to uncontrollable factors received strong support.

Those who were depressed were more likely to

attribute negative outcomes to chance, a

variable that differentiated best between the

depressed and nondepressed groups. Further,

the depressed subjects were more external in

locus of control orientation. Low self-esteem

and somewhat increased feelings of deservingWhen analyses were rerun using the conservative Scheffe procedure to correct for error rate inflation, significant differences between the depressed

and nondepressed groups were again found on selfesteem, internal-external control, characterological

self-blame, and chance.

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

ness characterized the depressed population,

suggesting that characterological self-blame is

esteem related, not control related.

The results would have been considerably

more compelling if it were found that those

students who were not depressed engaged in

more behavioral self-blame than depressed

students, yet this was not the case. However,

it can perhaps be argued that the behavioral

self-blame reported by the depressed and

nondepressed populations differed in an important way; for the depressed group the behavioral self-blame co-occurred with characterological self-blame, and blaming one's

behavior was thus an extension of blaming

one's character. It may be difficult to blame

one's character without blaming one's behavior, yet it may be very possible to blame

one's behavior without blaming one's character. In the former instance the behavior

may be regarded as uncontrollable in that it

is a direct and unalterable extension of one's

character (i.e., controlled by one's character).

In the latter case the behavioral self-blame

does not reflect decreased self-esteem, but

rather the belief that one's behavior is modifiable. Perhaps behavioral self-blame, when

displayed in conjunction with characterological self-blame, is simply a further reflection

of characterological self-blame. However,

when it occurs alone it is likely to represent

an adaptive response, stemming from a desire

to maintain a belief in personal control following a negative outcome.

Study 2: Rape 7

Method

Respondents. Respondents were rape crisis centers

located throughout the United States. Center names

were derived primarily from a list located in a federal report on rape and its victims (Brodyaga et al.,

Note 3 ) ; this list was supplemented by names of

rape crisis centers found in an informal directory at

a local women's center. Services that were hotlines

only or were task forces without counseling services

were excluded from the final list. Questionnaires were

mailed to 120 centers representing 37 states and the

District of Columbia. Thirty of the questionnaires

were returned "addressee unknown." Of the remaining 90 crisis centers, 48 responded (53% return

rate; including those returned "addressee unknown,"

the return rate was 40%).

Questionnaire. In a cover letter I identified myself

as a social psychologist interested in the nature of

1805

self-blame among victims of rape; letter recipients

were asked to base their questionnaire responses on

their experiences as counselors of rape victims. The

questionnaire items dealt primarily with the issue of

self-blame. Crisis centers were asked to indicate

approximately how many rape victims they see yearly

and of those they see, the percentage who blame

themselves, at least in part, for the rape. The behavioral self-blame question asked, "Of the rape

victims you see, what percentage blame themselves

for the rape because of some behavior (act or omission) they engaged in at the time of or immediately

prior to the rape (e.g., 'I should not have walked

alone,' 'I should not have hitchhiked,' 'I should have

locked my windows') ?" The rape crisis centers were

then asked to provide specific examples of behavioral

self-blame related by the women they have counseled. The characterological self-blame question asked,

"Of the rape victims you see, what percentage blame

themselves for the rape because of some character

trait or personality flaw they believe they have (e.g.,

'I am so stupid, I deserved to be raped,' 'I'm the

kind of woman who attracts rapists,' 'I am a weak

person and can't say no') ?" Specific examples of this

type of blame were then requested as well. The

centers were also asked to indicate on two 7-point

scales, with endpoints almost not at all and completely, how much self-blaming characterized the

women who engaged in behavioral and characterological self-blame, respectively; this was included in

order to ascertain whether behavioral and characterological self-blamers differ in terms of the amount of

self-blame they attribute to themselves for the rape.

Results

Of the 48 rape crisis centers that responded,

38 completed the questionnaire, 6 wrote letters

providing general comments, and 4 wrote that

they did not provide direct counseling services

and were therefore unable to complete the

items. Results were therefore based on the

completed questionnaires of 38 centers. The

rape crisis centers differed markedly in the

scope of their operation, with the 3 smallest

serving 12, 30, and 40 rape victims yearly,

and the 3 largest serving 1,200, 1,250, and

1,500; the mean number of rape victims seen

across the centers was 335.

In general, self-blame was reported as quite

common; the reported mean percentage of

7

The results of this study were reported by the

author at the symposium "New Directions in Control Research" at the convention of the American

Psychological Association, Toronto, 1978. The author

thanks Chris Eagan for her invaluable help on the

project.

1806

RONNIE JANOFF-BULMAN

women who blamed themselves at least in part

for the rape was 14%. Of those who blamed

themselves, behavioral self-blame was reported

as considerably more common than characterological self-blame, and the differences between the reported incidence of the two blaming strategies was significant, F(\, 32) =

140.90, p < .001; an average of 69% of the

women were reported as blaming themselves

behaviorally, whereas an average of 19% were

reported as blaming themselves characterologically. Further, examples of the two types of

self-blame provided by the rape crisis centers

confirmed the fact that they were readily able

to distinguish between the two. Frequently

mentioned examples of behavioral self-blame

included the following: I shouldn't have let

someone I didn't know into the house, I

shouldn't have been out that late, I should not

have walked alone (in that neighborhood),

I should not have hitchhiked, I should not

have gone to his apartment, I shouldn't have

left my window open, I should have locked

my car. Examples of characterological selfblame that were frequently reported included:

I'm too trusting, I'm a weak person, I'm too

naive and gullible, I'm the kind of person who

attracts trouble, I'm not a very aware person,

I'm not at all assertiveI can't say no, I'm

immature and can't take care of myself, I'm

not a good judge of character, I'm basically a

bad person. It is perhaps worth noting that

examples of behavioral blame were, without

exception, reported in the past tense (i.e., I

should have/should not have), whereas examples of characterological self-blame were

presented in the present tense (I am/am not),

perhaps implicitly indicating the presumed

modinability/nonmodinability of factors associated with behavioral and characterological

self-blame respectively (cf. Elig & Freize,

1975). However, the examples of the two

types of self-blame provided in the questionnaire were consistent with the different tenses

reported in the examples of the crisis centers,

and this alone could have accounted for the

findings. The author did not realize that she

had made these distinctions on the questionnaire until the results clearly differentiated

between the tenses used for the two types of

self-blame. Finally, in responding to how

much women blamed themselves for the rape,

the centers reported that characterological

self-blamers blamed themselves significantly

more for the rape than did behavioral selfblamers (3.92 vs. 3.23), F(l, 25) = 11.29,

p < .002.

Discussion

The rape crisis center counselors reported

that the majority of rape victims do blame

themselves, at least in part, following the

rape. However, the focus of this self-attribution is a behavioral act or omission engaged in

at the time of (or immediately preceding) the

rape. Fewer than one-fifth of the women

served by the centers blamed themselves in a

characterological way, evidence that the "popular" view of the masochistic rape victim who

perceives herself as worthless is largely unfounded. Rather, the self-blame in which most

rape victims engage may represent a control

maintenance strategy, a functional response

to a traumatic event. Given the large discrepancies between those who blame themselves

behaviorally and characterologically, it follows that most women clearly blame themselves in a behavioral manner only and do not

combine this response with characterological

self-blame, as may be the case with depressives (see above). In suggesting that behavioral self-blame reflects a positive impulse in

rape victims, there is no intention of implying that the rape was the woman's fault. It is

even likely that the woman who engages in

behavioral self-blame does not do so to the

exclusion of blaming the rapist, society, or

other factors. These blame attributions, instead, would stem from different motivations,

control maintenance being the motivation

behind self-blame.

Two potentially serious objections to this

study require a response. First, many of the

women who volunteer or work in rape crisis

centers may be ardent feminists who would

be more likely to indicate that women blame

themselves behaviorally rather than characterologically, for the latter suggests that

women see themselves as worthless. In response, if the crisis center workers truly

wanted to present women in a positive light,

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

they would have indicated quite simply that

women infrequently blame themselves. Further, there was nothing in the questionnaire

or cover letter to indicate that one type of

self-blame was "healthier" than another, and

several counselors commented that they had

never before distinguished between types of

self-blame but that it appeared interesting to

them. Comments by the counselors indicated

that these women were concerned about the

health of the women they served and that preserving a positive image of womanhood in

general was clearly not central to their activities as rape counselors. The second criticism

that could be raised is potentially more serious. It is that women who go to rape crisis

centers are most likely to be individuals who

do not blame themselves characterologically

and do not feel they deserved to be raped.

Thus, there is a self-selected population of

behavioral self-blamers served by rape crisis

centers. It is difficult to counter this claim, for

there is probably much truth to it. One must

realize, however, that the literature written

on rape is almost entirely derived from

women who seek help after rape and not from

women who quietly keep the trauma to themselves, ashamed to talk about it or admit it.

The pervasiveness of self-blame documented

in the rape literature is drawn primarily from

observations of women at rape crisis centers,

from women's centers, or from women who

agree to be interviewed by researchers, also a

population likely to be self-selected. Thus, the

negative image of the rape victim engaging in

masochistic, maladaptive self-blame derives

from a rape victim population likely to be

very similar to that served by the rape crisis

centers surveyed. It might also be mentioned

that those women who have least difficulty

coping with the rape and who are apt to be

behavioral self-blamers are probably also

missing from the rape center population, for

they may not require help (outside their own

circle of family and friends) following the

rape. Perhaps it is sufficient to point out that

within the population of women served by

rape crisis centers, self-blame has been improperly understood as self-derogating, reflecting the woman's belief in her own worthlessness, rather than as a response that

1807

reflects a positive attempt to reestablish personal control.

General Conclusions and Implications

Self-blame appears to be a label for two

very different self-attributions, characterological self-blame being esteem related, and behavioral self-blame being control related. Selfblame as a predictor of good coping and selfblame as a concomitant of depression are no

longer inconsistent in light of the two types

of self-blame. Further, the paradox in depressionthat individuals are simultaneously

helpless and self-blamingcan be resolved if

characterological self-blame characterizes depressives and differentiates them from nondepressed individuals. The division of selfblame into two different phenomena even has

political or cultural implications, for selfblame by a victimized group such as rape victims can now be understood in such a manner

as to preclude the perpetuation of a negative

image of the group in question. It is perhaps

unfortunate that one term has been used as

a label for these two different self-attributions,

for the singular term self-blame blurs important distinctions between adaptive and

maladaptive responses to failures and victimizations. Since popularly the term has

negative connotations, it would perhaps be

desirable to provide a more neutral label for

behavioral self-blame. Particularly in the case

of rape, this would render more politically

palatable the proposition that behavioral

self-blame is of functional value for victims

of rape.

The recognition of two types of self-blame

may have therapeutic implications. Seligman's

(197S) control-oriented strategies continue to

seem appropriate for depressives, whose selfblaming does not imply high perceived control, but rather lack of control. Further, a

cognitive therapy that entails reattributing

the focus of one's attributions (e.g., from

character to behavior) might be of value in

treating depressives. In general, leading people to focus on behaviors that are alterable,

rather than on their relatively nonmodifiable,

more global character, may increase perceived

future avoidability of negative events and

1808

RONNIE JANOFF-BULMAN

perceived control in general, outcomes that

would presumably be of positive value.

Dweck's (1975) successful reattribution training with helpless students, involving reattributing their ability attributions for failure to

effort attributions, suggests the potential of

such cognitive strategies using self-blame.

In the case of rape, the control concerns

that may be implicit in the rape victim's selfblame often seem to be ignored in counseling,

not because they are regarded as unimportant,

but because they may go unrecognized. One

counseling technique for rape victims includes

repeatedly telling a woman that there is nothing she could have done to avoid the rape,

that it was entirely the rapist's doing and outside of her control. Although meant to be

reassuring, these statements could conceivably be not at all helpful, in light of the

proposition that the women are seeking to reestablish a sense of control. Rather, counselors

should perhaps recognize the functional value

of behavioral self-blame and concentrate on

enabling the victim to reestablish a belief in

her relative control over life outcomes (e.g.,

discussing possible ways of minimizing the

likelihood of a future rape). Too often, behavioral self-blame is regarded as detrimental

to mental health. Rather, it may serve as an

indicator of the victim's psychological needs

at the time.

Behavioral and characterological self-blame

appear to be distinct reactions yet are far

from fully understood. Ideas raised in this

paper have been tested only with female subjects and thus may not generalize to other

populations; this issue of generalizability particularly calls for research with male subjects.

Further, the relationship between the two

types of self-blame would appear to be a

fruitful area for future study. Does behavioral

self-blame that occurs with characterological

self-blame, for example, lose its adaptive

value, or is it similar to behavioral blame that

occurs without characterological self-blame?

Is characterological self-blame that occurs

without behavioral self-blame more or less

maladaptive than characterological self-blame

that occurs with behavioral self-blame? In

addition, longitudinal studies designed to tap

the coping implications of these two types of

self-blame would be important contributions

to our understanding of the relationship between coping and attributional strategies.

Another possible direction lies in the area of

blaming strategies by help-givers. Brickman

and his colleagues (Brickman et al., Note 4)

have presented a compelling case for the psychological tensions that exist between conditions that render helping appropriate (i.e.,

regarding the recipient of help as not responsible) and conditions that render helping

effective (i.e., attributing responsibility to

the recipient of help). That is, one is apt to

help an individual who is not to blame for a

misfortune, yet this attribution minimizes the

belief that one's help will be effective. Perhaps training both help-givers and recipients

of help to hold behavioral blame orientations

(as opposed to characterological blame orientations) would help resolve the existing tensions. Last, the therapeutic implications of

the two types of self-blamebehavioral and

characterologicalremain an area ripe for

future study.

Reference Notes

1. Bryant, G., & Cirel, P. A community response to

rape: An exemplary project (Polk County Rape/

Sexual Assault Care Center). Washington, D.C.:

National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, 1977.

2. Haley, W. E., & Strickland, B. R. Locus of control

and depression. Paper presented at the meeting

of the Eastern Psychological Association, Boston,

1977.

3. Brodyaga, L., Gates, M., Singer, S., Tucker, M.,

& White, R. Rape and its victims: A report for

citizens, health facilities, and criminal justice

agencies. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of

Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, 1975.

4. Brickman, P., Rabinowitz, V. C., Coates, D., Cohn,

E., Kidder, L., & Karuza, J. Helping. Unpublished

manuscript, University of Michigan, 1979.

References

Abramson, L. Y., & Sackeim, H. A. A paradox in depression: Uncontrollability and self-blame. Psychological Bulletin, 1977, 84, 838-8S1.

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale,

J. D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique

and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1978, 87, 49-74.

Amir, M. Patterns in forcible rape. Chicago, 111.: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

SELF-BLAME: DEPRESSION AND RAPE

Bard, N., & Ellison, K. Crisis intervention and investigation of forcible rape. The Police Chief, 1974,

41, 68-73.

Beck, A. T. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and

theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row,

1967.

Bowers, K. Pain, anxiety, and perceived control.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

1968, 32, 596-602.

Brownmiller, S. Against our will: Men, women, and

rape. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975.

Bulman, R. J., & Wortman, . B. Attributions of

blame and coping in the "real world": Severe accident victims react to their lot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1977, 35, 351-363.

Burgess, A. W., & Holmstrom, L. L. Rape trauma

syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1974,

131, 981-985. (a)

Burgess, A. W., & Holmstrom, L. L. Rape: Victims

of crisis. Bowie, Md.: Robert J. Brady, 1974. (b)

Burgess, A. W., & Holmstrom, L. L. Coping behavior

of the rape victim. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1976, 133, 413-318.

Dweck, C. S. The role of expectations and attributions in the alleviation of learned helplessness.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1975,

31, 674-685.

Eagly, A. H. Involvement as a determinant of response to favorable and unfavorable information.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Monograph, 1967, 7(3, Pt. 2).

Elig, T., & Frieze, I. A multidimensional scheme for

coding and interjecting perceived causality for

success and failure events: The coding scheme of

perceived causality (CSPC). JSAS: Catalog of

Selected Documents in Psychology, 1975, 5, 313.

(Ms. No. 1069)

Glass, D., & Singer, J. Urban stress. New York:

Academic Press, 1972.

Griffin, S. Rape: The ail-American crime. Ramparts

Magazine, 1971, 10, 26-35.

Harvey, M. D., & Rule, B. G. Moral evaluations and

judgments of responsibility. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 1978, 4, 583-588.

Hilberman, E. Rape: The ultimate violation of the

self. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1976, 133,

436-437.

Hursch, C. H. The trouble with rape. Chicago:

Nelson-Hall, 1977.

Kelley, H. H. Attribution in social interaction. Morristown, N.J.: General Learning Press, 1971.

Langer, E. J., & Rodin, J. The effects of choice and

enhanced responsibility for the aged: A field ex-

1809

periment in an institutional setting. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 1976, 33, 951955.

Lerner, M. J., & Miller, D. T. Just world research

and the attribution process: Looking back and

ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 1978, 85, 1030-1051.

Medea, A., & Thompson, K. Against rape. New York:

Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1974.

National Commission on the Causes and Prevention

of Violence. Crimes of violence (Vol. 2). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969.

Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric theory. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Rotter, J. B. Generalized expectancies for internal

versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 1966, 80(1, Whole No. 609).

Schulz, R. Effects of control and predictability on the

physical and psychological well-being of the institutionalized aged. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 1976, 33, 563-573.

Seligman, M. E. P. Helplessness: On depression, development and death. San Francisco: Freeman,

1975.

Spielberger, C. D. Anxiety as an emotional state. In

C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety: Current trends

in theory and research (Vol. 1). New York:

Academic Press, 1972.

Walster, E. Assignment of responsibility for an accident. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

1966, 3, 73-79.

Weiner, B. Achievement motivation as conceptualized

by an attribution theorist. In B. Weiner (Ed.),

Achievement Motivation and attribution theory.

Morristown, N.J.: General Learning Press, 1974.

Weiner, B., Frieze, L, Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S.,

& Rosenbaum, R. M. Perceiving the causes of success and failure. New York: General Learning

Press, 1971.

Weis, K., & Weis, S. Victimology and the justification of rape. In I. Drapkin & E. Viano (Eds.),

Exploiters and exploited: Vol. /. Victimology: A

new focus. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books,

1975.

Wortman, C. B., & Dintzer, L. Is an attributional

analysis of the learned helplessness phenomenon

viable? A critique of the Abramson-SeligmanTeasdale reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1978, 87, 75-90.

Zung, W. K. A self-rating depression scale. Archives

of General Psychiatry, 1965, 12, 63-70.

Received November 21, 1978

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Access To Public Records in NevadaDokumen32 halamanAccess To Public Records in NevadaLas Vegas Review-JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Right To Freedom of Religion With Respect To Anti-Conversion LawsDokumen11 halamanRight To Freedom of Religion With Respect To Anti-Conversion LawsAditya SantoshBelum ada peringkat

- Little Truble in DublinDokumen9 halamanLittle Truble in Dublinranmnirati57% (7)

- Anatomy and Physiology of Male Reproductive SystemDokumen8 halamanAnatomy and Physiology of Male Reproductive SystemAdor AbuanBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digest Guidelines Template USE THIS SL PATDokumen4 halamanCase Digest Guidelines Template USE THIS SL PATAnselmo Rodiel IVBelum ada peringkat

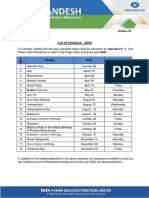

- Holiday List - 2020Dokumen3 halamanHoliday List - 2020nitin369Belum ada peringkat

- Succession ExplainedDokumen211 halamanSuccession ExplainedGoodFather100% (3)

- Angels MedleyDokumen7 halamanAngels MedleywgperformersBelum ada peringkat

- Waiver Declaration For Community OutreachDokumen2 halamanWaiver Declaration For Community OutreachRahlf Joseph TanBelum ada peringkat

- 18 2023 6 39 14 AmDokumen5 halaman18 2023 6 39 14 AmIsa Yahya BayeroBelum ada peringkat

- Young Beth Jacob!: Morning AfternoonDokumen2 halamanYoung Beth Jacob!: Morning AfternoonbjsdBelum ada peringkat

- Raport Kroll II OcrDokumen154 halamanRaport Kroll II OcrSergiu BadanBelum ada peringkat

- Information MURDERDokumen2 halamanInformation MURDERGrester FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- MSDM Internasional: Ethics and Social Responsibility Case A New Concern For Human Resource ManagersDokumen8 halamanMSDM Internasional: Ethics and Social Responsibility Case A New Concern For Human Resource Managerselisa kemalaBelum ada peringkat

- 123Dokumen143 halaman123Renz Guiang100% (1)

- 7 MWSS Vs ACT THEATER INC.Dokumen2 halaman7 MWSS Vs ACT THEATER INC.Chrystelle ManadaBelum ada peringkat

- NocheDokumen13 halamanNocheKarlo NocheBelum ada peringkat

- Past Tenses ExercisesDokumen1 halamanPast Tenses ExercisesChristina KaravidaBelum ada peringkat

- Hist Cornell Notes Outline 3.3 .34Dokumen3 halamanHist Cornell Notes Outline 3.3 .34erinsimoBelum ada peringkat

- Soco v. MilitanteDokumen2 halamanSoco v. MilitanteBeeya Echauz50% (2)

- Ninety SeventiesDokumen6 halamanNinety Seventiesmuhammad talhaBelum ada peringkat

- From Berlin To JerusalemDokumen2 halamanFrom Berlin To JerusalemCarmenCameyBelum ada peringkat

- Let's - Go - 4 - Final 2.0Dokumen4 halamanLet's - Go - 4 - Final 2.0mophasmas00Belum ada peringkat

- Naruto Shiraga No Tensai by DerArdian-lg37hxmnDokumen312 halamanNaruto Shiraga No Tensai by DerArdian-lg37hxmnMekhaneBelum ada peringkat

- Costs and Consequences of War in IraqDokumen2 halamanCosts and Consequences of War in Iraqnatck96Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter III Workload of A Lawyer V2Dokumen8 halamanChapter III Workload of A Lawyer V2Anonymous DeTLIOzu100% (1)

- PoliLaw Arteche DigestsDokumen418 halamanPoliLaw Arteche DigestsnadinemuchBelum ada peringkat

- QuizDokumen2 halamanQuizmuhammad aamirBelum ada peringkat

- Resolution To Censure Graham - PickensDokumen12 halamanResolution To Censure Graham - PickensJoshua CookBelum ada peringkat

- Sofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementDokumen3 halamanSofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementJoyce ReisBelum ada peringkat