Complicated Grief Prevalence

Diunggah oleh

Ivonne CoronaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Complicated Grief Prevalence

Diunggah oleh

Ivonne CoronaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Affective Disorders

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j a d

Brief report

Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population

Daisuke Fujisawa a,b,c,, Mitsunori Miyashita d, Satomi Nakajima e, Masaya Ito e,f,

Motoichiro Kato b, Yoshiharu Kim e

a

Psycho-oncology Division, National Cancer Center East, Japan

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Keio University School of Medicine, Japan

Division of Palliative Care, Keio University Hospital, Japan

d

Department of Palliative Nursing, Health Science, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan

e

National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan

f

Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan

b

c

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 27 December 2009

Accepted 3 June 2010

Available online 1 July 2010

Keywords:

Prevalence

Determinant

Complicated grief

General population

Epidemiology

Cancer

a b s t r a c t

Background: Few epidemiological studies have examined complicated grief in the general

population, especially in Asian countries. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the prevalence

and predictors of complicated grief among community dwelling individuals in Japan.

Methods: A questionnaire survey regarding grief and related issues was conducted on

community dwelling individuals aged 4079 who were randomly sampled from census tracts.

Complicated grief was assessed using the Brief Grief Questionnaire. Stepwise logistic regression

analysis was conducted in order to identify predictors of complicated grief.

Results: Data from 969 responses (response rate, 39.9%) were subjected to analysis. The analysis

revealed 22 (2.4%) respondents with complicated grief and 272 (22.7%) with subthreshold

complicated grief. Respondents who were found to be at a higher risk for developing complicated

grief had lost their spouse, lost a loved one unexpectedly, lost a loved one due to stroke or cardiac

disease, lost a loved one at a hospice, care facility or at home, or spent time with the deceased

everyday in the last week of life.

Limitations: Limitations of this study include the small sample size, the use of self-administered

questionnaire, and the fact that the diagnoses of complicated grief were not based on robust

diagnostic criteria.

Conclusions: The point prevalence of complicated grief within 10 years of bereavement was 2.4%.

Complicated grief was maintained without signicant decrease up to 10 years after bereavement.

When subthreshold complicated grief is included, the prevalence of complicated grief boosts up to

a quarter of the sample, therefore, routine screening for complicated grief among the bereaved is

desired. Clinicians should pay particular attention to the bereaved families with abovementioned

risk factors in order to identify people at risk for future development of complicated grief.

2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Background

Grief, or the emotional reaction to bereavement, is a normal,

natural human experience. Most people manage to come terms

with grief over time. Nevertheless, it is associated with a period

Corresponding author. Psycho-oncology Division, National Cancer Center

East, Japan. 6-5-1 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa-shi, Chiba, Japan. Tel.: +81 4 7134

7013; fax: +81 4 7134 7026.

E-mail address: dai_fujisawa@yahoo.co.jp (D. Fujisawa).

0165-0327/$ see front matter 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.008

of intense suffering, and for some individuals, the grieving

process is disturbed and/or prolonged, which leads to a state of

complicated grief.

Complicated grief has been dened as a deviation from the

normal grief experience in terms of either the time course,

intensity, or both. It is associated with increased risk of negative

health consequences, including various physical symptoms,

depression, higher alcohol consumption, greater use of medical

services, higher functional impairment, decreased social participation, and higher mortality due to suicide and other

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

physical conditions (Ott, 2003; Prigerson et al., 1996; Stroebe

et al., 2007; Szanto et al., 1997; Utz et al., 2002).

Complicated grief resembles depression, but it does not

respond well to treatments that are effective for depression

(Reynolds et al., 1999). However, treatments designed specifically for complicated grief have been shown to be effective

(Schut and Stroebe, 2005; Shear et al., 2005). The known risk

factors for complicated grief include the circumstances surrounding death (the cause, place and unexpectedness of death),

the quality of the lost relationship, pre-bereavement caregiver

burden, the characteristics of the bereaved (religion, quality of

social support, personality, coping style), and concurrent

socioeconomic stressors (Stroebe et al., 2007). Therefore,

identication of complicated grief and its predictors is essential.

To date, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that

prolonged grief occurs in about 920% of a population

(Prigerson and Jacobs, 2001; Raphael et al., 2001), but the

prevalence rate shows wide variation depending upon the

social, cultural, and clinical background. Among clinical

samples, the prevalence rate has been reported as 18.6%

among hospitalized patients with unipolar depression at 16.4

(SD = 14.1) years after signicant loss (Kersting et al., 2009),

24.3% among bipolar disorder patients at a mean of 12.3

(SD = 11.3) years after a loss (Simon et al., 2005), and 31.1%

among a mixed sample of psychiatric outpatients at a mean of

10.4 (SD = 9.7) years since a loss (Piper et al., 2001). On the

other hand, relatively few epidemiological studies have been

conducted on non-clinical populations, and the majority of

these have been limited to shorter periods of time. For example,

Chiu et al. assessed bereaved family of cancer patients at mean

time of 8.9 months after bereavement and reported a 24.6%

prevalence of complicated grief (Chiu et al., 2009). Middleton

also reported a 9.2% prevalence of chronic grief at 14 months

from bereavement in a community-based sample (Middleton

et al., 1996).

Epidemiological studies on complicated grief have mostly

been conducted in Western cultures, while some preliminary

research has been conducted in Asia (Chiu et al., 2009;

Ghaffari-Nejad et al., 2007; Prigerson et al., 2002; Senanayake

et al., 2006). However, these data were mostly collected from

specic populations, such as victims of natural disasters

(Ghaffari-Nejad et al., 2007; Shear et al., 2006) or psychiatric

patients, with or without specic diagnoses such as unipolar

depression and bipolar disorders (Kersting et al., 2009; Piper

et al., 2001).

The present study aimed to explore the prevalence and

predictors of complicated grief in the general population.

Therefore, a questionnaire survey regarding bereavement

and related issues was conducted on community dwelling

individuals.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants were community dwelling individuals

aged 4079 years who had experienced bereavement within

the past ten years. Since a diagnosis of complicated brief cannot

be given within six month after bereavement (Prigerson et al.,

2009), those who had experienced bereavement within the

past six months were excluded. Furthermore, those who had

353

experienced the loss of a child were also excluded because grief

over a child's death has been consistently reported to be

prolonged, and the diagnostic reliability of complicated grief

among bereaved parents remains unclear (Dyregrov et al.,

2003; Stroebe et al., 2007).

2.2. Procedure

An anonymous questionnaire was mailed to a sample of

the general Japanese population. We identied four target

areas (Tokyo, the capital city; Miyagi prefecture, in eastern

Japan; Shizuoka prefecture, in central Japan; and Hiroshima,

in eastern Japan) in order to obtain a wide geographic

distribution for the nationwide sample. The four areas

included an urban metropolis (Tokyo) and mixed urbanrural areas (others). We initially identied 5000 subjects

using a stratied two-stage random sampling method of

residents from the four areas. We randomly selected 50

census tracts in each area and then selected 25 individuals

within each census tract, thus identifying 1250 individuals for

each area. In June 2009, questionnaires were mailed to these

potential participants and a reminder postcard was sent

2 weeks later. The protocol of this study was approved by the

institutional review board of the University of Tokyo.

2.3. Questionnaire

The questionnaire included items regarding the respondents' demographic background (age and gender), the time

since the most recent bereavement, the relationship with the

deceased, the cause and place of death of the deceased, and

the number of days in which the respondent spent time with

the deceased during the last week of life.

Complicated grief was assessed using the Brief Grief

Questionnaire (BGQ) (Shear et al., 2006). The BGQ is a veitem, self-administered questionnaire that evaluates trouble

accepting the death, interference of grief in their life, troubling

images or thoughts of the death, avoidance of things related to

the person who died, and feeling cut off or distant from other

people. Responses were rated as 0, not at all; 1, somewhat; or 2,

a lot. A previous report suggests that a total score of 8 or higher

on the BGQ indicated that a respondent was likely to develop

complicated grief, while a score ranging from 5 to 7 indicated

subthreshold complicated grief and a score of less than 5

indicated a respondent was unlikely to develop complicated

grief (Shear et al., 2006).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The presence of complicated grief was dened using the

previously established cutoff score described above (Shear

et al., 2006). The chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were

used to identify factors possibly correlated with the presence

of complicated grief. Subsequently, a stepwise binary logistic

regression analysis (backward selection) was performed with

presence of complicated grief as the dependent variable and

factors with signicant relationships identied by the abovementioned analysis as predictor variables. All p values were

two-tailed, and the level of statistical signicance was set at

p b 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 16.0J software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

354

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

3. Results

Of 5000 questionnaires that were distributed, 44 were

returned as undeliverable and 1970 responses were received

(response rate: 39.9 ). Of these, 63 were excluded because of

signicant missing data. Among the remaining responses, 808

were excluded because the respondents had not experienced

bereavement within the past ten years, 117 were excluded

because of bereavement within the past six months, and 7

were excluded because they had experienced the loss of a

child. Finally, a total 969 of responses were subjected to

analysis. The demographic data of the sample is shown in

Table 1.

The results of the BGQ are presented in Table 2 according

to severity of grief and sociodemographic variables. Among

all participants, 22 respondents (2.4%) had scores of 8 or

higher on the BGQ, and were thus considered too complicated

grief, and 272 respondents (22.7%) scored between 5 and 7,

and were considered to be suffering from some symptoms of

complicated grief (subthreshold complicated grief). Using the

chi-square test, signicant differences in BGQ score were

observed for gender, relationship with the deceased, whether

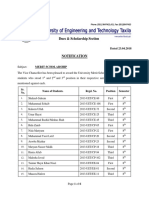

Table 1

Demographic data of the participants.

Gender

Age

Relationship with the deceased

Primary caregiver

Time from bereavement

Cause of death

Place of death

Expected death

Days spent with the deceased

during the end-of-life period

Male

Female

4049

5059

6069

7079

Spouse

Parent(s)

Parent(s)-in-law

Sibling(s)

Others

Yes

No

612 months

12 years

23 years

34 years

45 years

56 years

67 years

78 years

89 years

910 years

Cancer

Stroke

Cardiac disease

Others

Home

General hospital

Hospice/PCU

Care facility

Others

Expected death

Unexpected death

Everyday

46 day/week

13 day/week

None

Missing data

405

564

225

354

379

11

61

468

247

96

97

462

507

112

138

138

120

88

85

102

62

49

75

357

99

108

405

181

654

34

62

38

546

423

207

92

216

335

119

41.8

58.2

23.2

36.5

39.1

1.1

6.3

48.3

25.5

9.9

10.0

47.7

52.3

11.6

14.2

14.2

12.4

9.1

8.8

10.5

6.4

5.1

7.7

36.8

10.2

11.1

41.8

18.7

67.5

3.5

6.4

3.9

56.3

44.6

21.4

9.5

22.3

34.6

12.3

the respondent was the primary caregiver or not, cause and

place of death, whether the death was expected or unexpected, and days spent with the deceased during the end-oflife period.

Binary stepwise logistic regression analysis, with the

abovementioned determinant variables entered as predictor

variables, and the presence of complicated grief as the

dependent variable, demonstrated that relationship with

the deceased, the type of illness, the place of death, the

unexpectedness of death, and time spent with the deceased

during the end-of-life period were signicant predictors for

complicated grief (Table 3).

Compared with bereavement following the loss of a spouse,

bereavement following the loss of a parent or parent-inlaw contained a smaller risk for complicated grief (odds ratio

(OR) = 0.13, 95% condence interval (CI) = 0.050.35; OR=

0.19, 95%CI = 0.060.62, respectively). Those who lost a loved

one due to stroke or cardiac disease were more likely to

experience complicated grief than those who lost a loved one

due to cancer (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.105.32). Family members

of people who died in general hospitals were signicantly less

likely to experience complicated grief than family members of

people who died at home (OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.160.92).

Those who did not spent time with the deceased during the

end-of-life period were signicantly less likely to experience

complicated grief, compared with those who spent time with

the deceased everyday during the same period (OR = 0.07;

95% C.I.= 0.020.21).

4. Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that the point

prevalence of complicated grief within 10 years of bereavement is 2.4% among the general population. This gure is

comparable with that for major depressive disorder (2.1%),

and higher than the gure for anxiety disorders (0.40.9%) in

Japan (Kawakami et al., 2005).

In comparison with gures from studies conducted in other

countries, this prevalence is somewhat smaller. In Australian

non-clinical samples, the prevalence has been reported to range

from 8.8% to 9.2% at 13 months post-bereavement (Byrne and

Raphael, 1994) (Middleton et al., 1996). Among Taiwanese

caregivers who lost a loved one due to cancer, the prevalence of

complicated grief was 24.6% at a mean of 8.9 months postbereavement (Chiu et al., 2009). These differences can be

attributed to both cultural differences and the employment of

different criteria for diagnosing complicated grief. Stringent

diagnostic criteria for complicated grief have not yet been

established, and the prevalence of complicated grief varies

depending on which diagnostic criteria are used. For example, a

substantial discrepancy in the prevalence rate of complicated

grief had been noted in a general elderly sample, with a 0.9%

prevalence observed using Prigerson's criteria and a 4.2%

prevalence observed using Horowitz's criteria (Forstmeier

and Maercker, 2007). The former criteria include items related

to separation distress, traumatic distress, duration of more than

6 months, and disturbance that causes clinically signicant

impairment (Prigerson et al., 1999); while the latter criteria

include grief-related intrusions, behaviors that avoid griefrelated emotional stress, difculties in adapting to the loss, and

duration of more than 14 months with disturbance of daily

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

355

Table 2

Prevalence and severity of complicated grief.

Total

Gender

Age

Relationship with the deceased

Primary caregiver

Time from bereavement

Cause of death

Place of death

Expected death

Days spent with the deceased during

the end-of-life period

Male

Female

4049

5059

6069

7079

Spouse

Parent(s)

Parent(s)-in-law

Sibling(s)

Others

Yes

No

612 months

12 years

23 years

34 years

45 years

56 years

67 years

78 years

89 years

910 years

Cancer

Stroke

Cardiac disease

Others

Home

General hospital

Hospice/PCU

Care facility

Others

Expected

Unexpected

Everyday

46 days/week

13 days/week

None

Subthreshold complicated grief

(%)

Complicated grief

(%)

207

79

128

44

77

82

4

29

108

30

24

16

128

77

30

39

26

23

14

13

22

9

12

19

94

18

30

64

35

142

11

9

10

116

75

63

31

41

56

22.7

20.6

24.2

20.5

23.0

23.3

40.0

50.0

24.5

12.9

27.6

16.8

29.7

16.1

28.3

28.9

19.8

20.5

16.5

16.7

23.4

15.8

25.5

28.4

28.2

19.6

28.6

16.8

20.6

23.0

35.5

15.3

29.4

21.6

25.1

31.0

34.4

19.1

17.1

22

4

18

6

7

8

1

5

11

2

3

1

13

9

2

3

2

1

5

2

1

3

0

3

9

5

3

5

2

16

1

0

3

8

11

10

3

1

5

2.4

1.0

3.4

2.8

2.1

2.3

10.0

8.6

2.5

0.9

3.4

1.1

3.0

1.9

1.9

2.2

1.5

0.9

5.9

2.6

1.1

5.3

0.0

4.5

2.7

5.4

2.9

1.3

1.2

2.6

3.2

0.0

8.8

1.5

3.7

4.9

3.3

0.5

1.5

p

0.02

0.48

b 0.001

b 0.001

0.19

b 0.01

0.04

0.05

b 0.001

PCU: palliative care unit.

* p b 0.05.

functioning (Horowitz et al., 1997). The BGQ, the instrument

used in the present study, contains items derived from both

criteria (trouble accepting the death from Horowitz's criteria,

and avoidance, intrusive thoughts and feeling distant from

other people from Prigerson's criteria. Therefore, the item

structure of the BGG could explain why the prevalence of

complicated grief observed in the present study lies between

those measured using the criteria of Horowitz and Prigerson.

When subthreshold complicated grief is included, the

prevalence of complicated grief rises to as high as 25.1%,

implying that approximately a quarter of all bereaved people

are at risk for developing complicated grief.

One of the most important ndings in the present study is

that the prevalence of complicated grief does not show a

signicant decline in the years after bereavement. Before

conducting this study, we hypothesized that the prevalence of

complicated grief declines over time, but our results contradicted our hypothesis. This nding implies that complicated

grief, for individuals who suffer from it, is maintained for many

years and does not resolve spontaneously. Among the

population with psychiatric morbidity, complicated grief has

been observed a remarkably long time after bereavement

(prevalence range, 18.631.1%; range of time after bereavement, 10.416.4 years) (Kersting et al., 2009; Piper et al., 2001;

Simon et al., 2005). Our study demonstrated that long-standing

complicated grief is observed even among the general

population. However, further study is needed in order to

investigate whether the maintenance of complicated grief is

mediated by the presence of other psychiatric conditions.

The relationship with the deceased, type of illness, place of

death, unexpectedness of death, and time spent with the

deceased during the end-of-life period were extracted as

signicant predictors for complicated grief. Concerning the

relationship with the deceased, bereavement following the loss

of a spouse contained the highest risk when compared with

bereavement following the loss of a sibling, parent or parent-inlaw. It has generally been considered in Eastern cultures that

the parent-offspring relationship is more cherished than

spousal relationships, whereas the inverse is true in Western

cultures (Bernard and Guarnaccia, 2003). Contrary to this

general perception, among the present sample, complicated

grief was more frequently seen in spousal relationships. This

356

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

Table 3

Binary logistic regression analysis of predictive variables for presence of complicated grief.

Gender

Relationship (vs. spouse)

Parents

Parents-in-law

Siblings

Others

Primary carer

Type_of_Illness (vs cancer)

Stroke

Cardiac

Others

Place_of_Death (vs. home)

General hospital

Hospice

Care facility

Others

Unexpected death

Days spent with the deceased during

end-of-life period (vs. everyday)

46 days/week

13 days/week

None

Beta

S.D.

Wald

d.f.

0.3

0.3

2.0

1.7

0.7

0.7

0.2

0.5

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.4

1.3

1.2

1.0

0.5

0.5

0.5

1.0

2.7

2.7

3.0

0.9

0.4

0.6

0.7

0.6

0.4

0.8

51.6

16.6

7.6

1.3

1

0.2

26.5

6.1

5.5

4.2

125.0

4.7

18.5

15.7

22.2

4.9

39.0

1

4

1

1

1

0.43

1

3

1

1

1

4

1

1

1

1

1

3

0.37

b0.001

b0.001

b0.01

0.25

1.72

0.68

b0.001

0.01

0.02

0.04

b0.001

b0.05

b0.001

b0.001

b0.001

0.03

b0.001

0.8

0.6

2.7

0.5

0.5

0.6

1

1

1

0.11

0.21

b0.001

2.5

1.5

21.1

Exp (B)

95%

C.I.

Lower

Upper

0.74

0.38

1.43

0.13

0.19

2.02

0.44

1.19

0.05

0.06

0.61

0.52

0.35

0.62

6.77

6.66

2.74

3.58

3.35

0.36

1.31

1.22

0.13

9.79

9.19

0.95

0.38

14.73

15.61

19.84

2.42

0.16

4.32

4.01

5.72

1.10

0.92

50.18

60.80

68.76

5.32

2.13

0.53

0.07

0.84

0.20

0.02

5.42

1.44

0.21

S.D.: standard deviation.

d.f.: degree of freedom.

C.I.: condence interval.

may be the result of recent changes in familial structure in

Japan, which is becoming increasingly Westernized. Clinicians

should note that cultural difference exists among Asian

countries, and should not view patients in terms of the oversimplied model of Eastern vs. Western.

The respondents who lost a loved one due to stroke or

cardiac disease were more likely to experience complicated

grief than those who lost a loved one due to cancer. This may

be because stroke and cardiac disease are more likely to occur

unexpectedly, which leads to an increased likelihood of

complicated grief.

The place of death is another predictor of complicated

grief. Family members of people who died in general

hospitals are signicantly less likely to experience complicated grief than the family members of people who died at

home. The burden of care before bereavement has been

demonstrated to have negative effect on subsequent complicated grief; therefore, it can be speculated that the family

members of people who died at home may have experienced

higher caregiver burden, which might lead to poor adaptation

to bereavement (Rossi Ferrario et al., 2004; Schulz et al.,

2001). Surprisingly, those who lost a loved one in a hospice or

a care facility were found to be more likely to experience

complicated grief than those who lost a loved one at home. It

is possible that bereaved family members might be dissatised with the care provided in the facilities and feel regret that

they could not personally provide care. In fact, a past survey

demonstrated that the quality of care did not meet the

expectations of most bereaved families (Sanjo et al., 2008).

The timing of referral to a hospice is also associated with

satisfaction with end-of-life care, and up to 50% of bereaved

families who used a palliative care unit felt that the timing of

the referral to the palliative care unit was either too early or

too late (Morita et al., 2009). Furthermore, transferring a

loved one from a hospital to a hospice or a care facility caused

feelings of guilt among family members, because such an

action was perceived as a withdrawal from active participation in treatment and even as turning their back on their

loved one. Preferences for end-of-life care vary between

individuals, meaning that some prefer to spend their end-oflife period at home, while others prefer hospitals. It has been

reported that those who are of relatively older age, those who

prefer unawareness of death and pride and beauty in their

concept of good death are more likely to hope to die in a

general hospital than in a hospice (Sanjo et al., 2007).

Potential discordance between the preference of the bereaved and that of the deceased may have caused dissatisfaction and/or feelings of guilt concerning the place of death.

In Japanese clinical settings, the family's approval has the

strongest inuence on the nal decision (Sato et al., 2008).

Poor communication with the physician may have contributed to the negative feelings about transferring the patients

to hospice (Morita et al., 2004). Toward the end-of-life

period, the patient's family is expected to play a central role in

medical decision making, therefore, the family is faced with

increasing burden regarding end-of-life care, which may

contribute to the higher prevalence of subsequent grief

among those who used a hospice.

Respondents who spent time with the deceased everyday

during the end-of-life period were signicantly more likely to

experience complicated grief, compared with those who did

not spend time with the deceased during the same period. We

presume that the time spent together during this period is an

indicator of the quality of the bond between the respondent

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

and the deceased, meaning that those who had strong bond

with the deceased spent more time with the deceased during

the end-of-life period and were, therefore, more likely to

experience complicated grief. Another possible interpretation

is that those who spend every day with the deceased during

the last week of life experienced heavier caregiver burden,

which lead to an increased risk of subsequent complicated

grief (Rossi Ferrario et al., 2004; Schulz et al., 2001).

This study contains some limitations. First, the response rate

was low, although the rate was acceptable for a mail-based

survey conducted on the general population. Second, the

background variables of the non-respondents are unknown;

therefore, we cannot rule out that the demographic distribution

of the sample was skewed. However, the distributions of the

cause and place of death are quite similar to the national

statistics. For example, the proportion of deaths in Japan due to

cancer, stroke and cardiac disease are 30.0%, 15.9%, and 11.1%,

respectively, and place of death is 12.7% for home, 81.1% for

hospital, and 3.9% for care facility (Japan Ministry of Health and

Labor). Third, the reliability of the data was compromised

because the data solely depended on the participants' selfreports. Finally, the diagnostic reliability of complicated grief is

relatively weak as denite diagnostic criteria for complicated

grief have yet to been established, although more stringent

criteria are currently under consideration (Forstmeier and

Maercker, 2007; Prigerson et al., 2009).

Despite these limitations, our results are noteworthy

because this is the rst epidemiological study to investigate

the prevalence and risk factors of complicated grief in the

general population in Japan. In consideration of the fact that

complicated grief is highly inuenced by cultural background,

our report should be considered pioneering research on

complicated grief in Asia.

In conclusion, our population-based study revealed that

point prevalence of complicated grief within 10 years of

bereavement is 2.4%, which is comparable with other common

mental disorders. Complicated grief seems to be maintained for

a long time, without decrease even 10 years after bereavement.

The spouse of a patient, those who have lost a loved one

unexpectedly, due to stroke or cardiac disease, those who have

lost one in a hospice, care facility or at home, and those who

spent time with the deceased everyday in the last week of life

are at higher risk for complicated grief. Clinicians should pay

particular attention to these predictors in order to identify

people at risk for future development of complicated grief.

When subthreshold complicated grief is included, the prevalence of complicated grief boosts up to a quarter of the sample,

therefore, routine screening for complicated grief among the

bereaved is desired. Further study implication includes prevalence study using the more stringent criteria that have been

proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11 and assessing other psychiatric

morbidities.

Role of funding source

This study was fully supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research

endowed to M.M from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan

(MHLW); the MHLW had no further role in study design; in the collection,

analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the

decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conict of Interest

All the authors declare no conicting interests.

357

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to Rieko Kimura, R.N. for

coordinating the study.

References

Bernard, L.L., Guarnaccia, C.A., 2003. Two models of caregiver strain and

bereavement adjustment: a comparison of husband and daughter

caregivers of breast cancer hospice patients. Gerontologist 43, 808816.

Byrne, G.J., Raphael, B., 1994. A longitudinal study of bereavement phenomena

in recently widowed elderly men. Psychol. Med. 24, 411421.

Chiu, Y.W., Huang, C.T., Yin, S.M., Huang, Y.C., Chien, C.H., Chuang, H.Y., 2009.

Determinants of complicated grief in caregivers who cared for terminal

cancer patients. Support Care Cancer.

Dyregrov, K., Nordanger, D., Dyregrov, A., 2003. Predictors of psychosocial

distress after suicide, SIDS and accidents. Death Stud. 27, 143165.

Forstmeier, S., Maercker, A., 2007. Comparison of two diagnostic systems for

complicated grief. J. Affect. Disord. 99, 203211.

Ghaffari-Nejad, A., Ahmadi-Mousavi, M., Gandomkar, M., Reihani-Kermani,

H., 2007. The prevalence of complicated grief among Bam earthquake

survivors in Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 10, 525528.

Horowitz, M.J., Siegel, B., Holen, A., Bonanno, G.A., Milbrath, C., Stinson, C.H.,

1997. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry

154, 904910.

Japan Ministry of Health and Labor. Japan Ministry of Health and Labor

database system for statistics. [http://www.e-stat.go.jp/] (last accessed

2010/06/15).

Kawakami, N., Takeshima, T., Ono, Y., Uda, H., Hata, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakane, H.,

Iwata, N., Furukawa, T.A., Kikkawa, T., 2005. Twelve-month prevalence,

severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in

Japan: preliminary nding from the World Mental Health Japan Survey

20022003. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 59, 441452.

Kersting, A., Kroker, K., Horstmann, J., Ohrmann, P., Baune, B.T., Arolt, V.,

Suslow, T., 2009. Complicated grief in patients with unipolar depression.

J. Affect. Disord. 118, 201204.

Middleton, W., Burnett, P., Raphael, B., Martinek, N., 1996. The bereavement

response: a cluster analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 169, 167171.

Morita, T., Akechi, T., Ikenaga, M., Kizawa, Y., Kohara, H., Mukaiyama, T.,

Nakaho, T., Nakashima, N., Shima, Y., Matsubara, T., Fujimori, M.,

Uchitomi, Y., 2004. Communication about the ending of anticancer

treatment and transition to palliative care. Ann. Oncol. 15, 15511557.

Morita, T., Miyashita, M., Tsuneto, S., Sato, K., Shima, Y., 2009. Late referrals to

palliative care units in Japan: nationwide follow-up survey and effects of

palliative care team involvement after the Cancer Control Act. J. Pain

Symptom Manage. 38, 191196.

Ott, C.H., 2003. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical

health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud. 27,

249272.

Piper, W.E., Ogrodniczuk, J.S., Azim, H.F., Weideman, R., 2001. Prevalence of

loss and complicated grief among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr.

Serv. 52, 10691074.

Prigerson, H., Jacobs, S., 2001. Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder: a

rationale, consensus criteria, and a preliminary empirical test. In:

Stroebe, M.S., Hansson, R.O., Stroebe, W., Schut, H. (Eds.), Handbook of

bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. American

Psychological Association, Washington, pp. 613645.

Prigerson, H.G., Bierhals, A.J., Kasl, S.V., Reynolds III, C.F., Shear, M.K.,

Newsom, J.T., Jacobs, S., 1996. Complicated grief as a disorder distinct

from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study.

Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 14841486.

Prigerson, H.G., Shear, M.K., Jacobs, S.C., Reynolds III, C.F., Maciejewski, P.K.,

Davidson, J.R., Rosenheck, R., Pilkonis, P.A., Wortman, C.B., Williams, J.B.,

Widiger, T.A., Frank, E., Kupfer, D.J., Zisook, S., 1999. Consensus criteria for

traumatic grief. A preliminary empirical test. Br. J. Psychiatry 174, 6773.

Prigerson, H., Ahmed, I., Silverman, G.K., Saxena, A.K., Maciejewski, P.K.,

Jacobs, S.C., Kasl, S.V., Aqeel, N., Hamirani, M., 2002. Rates and risks of

complicated grief among psychiatric clinic patients in Karachi, Pakistan.

Death Stud. 26, 781792.

Prigerson, H.G., Horowitz, M.J., Jacobs, S.C., Parkes, C.M., Aslan, M., Goodkin,

K., Raphael, B., Marwit, S.J., Wortman, C., Neimeyer, R.A., Bonanno, G.,

Block, S.D., Kissane, D., Boelen, P., Maercker, A., Litz, B.T., Johnson, J.G.,

First, M.B., Maciejewski, P.K., 2009. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med.

6, e1000121.

Raphael, B., Minkov, C., Dobson, M., 2001. Psychotherapeutic and pharmacological intervention for bereaved peersons. In: M.S., S., Hansson, R.O.,

358

D. Fujisawa et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 127 (2010) 352358

Stroebe, W., Schit, H. (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research:

Consequences, coping and care. American Psychological Association,

Washington DC, pp. 587612.

Reynolds III, C.F., Miller, M.D., Pasternak, R.E., Frank, E., Perel, J.M., Cornes, C.,

Houck, P.R., Mazumdar, S., Dew, M.A., Kupfer, D.J., 1999. Treatment of

bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a controlled

study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and

interpersonal psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 156, 202208.

Rossi Ferrario, S., Cardillo, V., Vicario, F., Balzarini, E., Zotti, A.M., 2004.

Advanced cancer at home: caregiving and bereavement. Palliat. Med. 18,

129136.

Sanjo, M., Miyashita, M., Morita, T., Hirai, K., Kawa, M., Akechi, T., Uchitomi, Y.,

2007. Preferences regarding end-of-life cancer care and associations

with good-death concepts: a population-based survey in Japan. Ann.

Oncol. 18, 15391547.

Sanjo, M., Miyashita, M., Morita, T., Hirai, K., Kawa, M., Ashiya, T., Ishihara, T.,

Miyoshi, I., Matsubara, T., Nakaho, T., Nakashima, N., Onishi, H., Ozawa, T.,

Suenaga, K., Tajima, T., Hisanaga, T., Uchitomi, Y., 2008. Perceptions of

specialized inpatient palliative care: a population-based survey in Japan.

J. Pain Symptom Manage. 35, 275282.

Sato, K., Miyashita, M., Morita, T., Sanjo, M., Shima, Y., Uchitomi, Y., 2008.

Quality of end-of-life treatment for cancer patients in general wards and

the palliative care unit at a regional cancer center in Japan: a

retrospective chart review. Support. Care Cancer 16, 113122.

Schulz, R., Beach, S.R., Lind, B., Martire, L.M., Zdaniuk, B., Hirsch, C., Jackson, S.,

Burton, L., 2001. Involvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a

spouse: ndings from the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 285,

31233129.

Schut, H., Stroebe, M.S., 2005. Interventions to enhance adaptation to

bereavement. J. Palliat. Med. 8 (Suppl 1), S140147.

Senanayake, H., de Silva, D., Premaratne, S., Kulatunge, M., 2006. Psychological reactions and coping strategies of Sri Lankan women carrying fetuses

with lethal congenital malformations. Ceylon Med. J. 51, 1417.

Shear, K., Frank, E., Houck, P.R., Reynolds III, C.F., 2005. Treatment of

complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293, 26012608.

Shear, K.M., Jackson, C.T., Essock, S.M., Donahue, S.A., Felton, C.J., 2006.

Screening for complicated grief among Project Liberty service recipients

18 months after September 11, 2001. Psychiatr. Serv. 57, 12911297.

Simon, N.M., Pollack, M.H., Fischmann, D., Perlman, C.A., Muriel, A.C., Moore,

C.W., Nierenberg, A.A., Shear, M.K., 2005. Complicated grief and its correlates

in patients with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66, 11051110.

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., Stroebe, W., 2007. Health outcomes of bereavement.

Lancet 370, 19601973.

Szanto, K., Prigerson, H., Houck, P., Ehrenpreis, L., Reynolds III, C.F., 1997.

Suicidal ideation in elderly bereaved: the role of complicated grief.

Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 27, 194207.

Utz, R.L., Carr, D., Nesse, R., Wortman, C.B., 2002. The effect of widowhood on

older adults' social participation: an evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. Gerontologist 42, 522533.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Elliptic FunctionsDokumen66 halamanElliptic FunctionsNshuti Rene FabriceBelum ada peringkat

- Character Interview AnalysisDokumen2 halamanCharacter Interview AnalysisKarla CoralBelum ada peringkat

- Iron FoundationsDokumen70 halamanIron FoundationsSamuel Laura HuancaBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning StudiesDokumen93 halamanEvaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studiesmario100% (3)

- C - TS4CO - 2021: There Are 2 Correct Answers To This QuestionDokumen54 halamanC - TS4CO - 2021: There Are 2 Correct Answers To This QuestionHclementeBelum ada peringkat

- Managing a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisDokumen15 halamanManaging a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisGareth McKnight100% (2)

- Canyon Colorado Electrical Body Builders Manual Service Manual 2015 en USDokumen717 halamanCanyon Colorado Electrical Body Builders Manual Service Manual 2015 en USAlbertiniCongoraAsto100% (1)

- Dreams FinallDokumen2 halamanDreams FinalldeeznutsBelum ada peringkat

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDokumen6 halamanDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDBelum ada peringkat

- Alphabet Bean BagsDokumen3 halamanAlphabet Bean Bagsapi-347621730Belum ada peringkat

- Summer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterDokumen6 halamanSummer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterRedwood Coast Land ConservancyBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Accounting and ReportingDokumen31 halamanFinancial Accounting and ReportingBer SchoolBelum ada peringkat

- Study Habits Guide for Busy StudentsDokumen18 halamanStudy Habits Guide for Busy StudentsJoel Alejandro Castro CasaresBelum ada peringkat

- Polisomnografí A Dinamica No Dise.: Club de Revistas Julián David Cáceres O. OtorrinolaringologíaDokumen25 halamanPolisomnografí A Dinamica No Dise.: Club de Revistas Julián David Cáceres O. OtorrinolaringologíaDavid CáceresBelum ada peringkat

- GravimetryDokumen27 halamanGravimetrykawadechetan356Belum ada peringkat

- Structuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesDokumen16 halamanStructuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesK.M. Weiland82% (11)

- Price and Volume Effects of Devaluation of CurrencyDokumen3 halamanPrice and Volume Effects of Devaluation of Currencymutale besaBelum ada peringkat

- Computer Conferencing and Content AnalysisDokumen22 halamanComputer Conferencing and Content AnalysisCarina Mariel GrisolíaBelum ada peringkat

- Cookery-10 LAS-Q3 Week5Dokumen7 halamanCookery-10 LAS-Q3 Week5Angeline Cortez100% (1)

- Sample PPP Lesson PlanDokumen5 halamanSample PPP Lesson Planapi-550555211Belum ada peringkat

- Beyond Digital Mini BookDokumen35 halamanBeyond Digital Mini BookAlexandre Augusto MosquimBelum ada peringkat

- Napolcom. ApplicationDokumen1 halamanNapolcom. ApplicationCecilio Ace Adonis C.Belum ada peringkat

- Voluntary Vs MandatoryDokumen5 halamanVoluntary Vs MandatoryGautam KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Hand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisDokumen68 halamanHand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisSuren VishvanathBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of LeadershipDokumen24 halamanTheories of Leadershipsija-ekBelum ada peringkat

- Friday August 6, 2010 LeaderDokumen40 halamanFriday August 6, 2010 LeaderSurrey/North Delta LeaderBelum ada peringkat

- Haryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignDokumen18 halamanHaryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignAnime SketcherBelum ada peringkat

- 2nd YearDokumen5 halaman2nd YearAnbalagan GBelum ada peringkat

- Myrrh PDFDokumen25 halamanMyrrh PDFukilabosBelum ada peringkat

- Algebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsDokumen8 halamanAlgebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsGambit KingBelum ada peringkat