Kyungsim Hong Nam

Diunggah oleh

Khye TanHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Kyungsim Hong Nam

Diunggah oleh

Khye TanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

SYSTEM

System 34 (2006) 399415

www.elsevier.com/locate/system

Language learning strategy use of ESL students in

an intensive English learning context

Kyungsim Hong-Nam *, Alexandra G. Leavell

Department of Teacher Education and Administration, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203, USA

Received 5 September 2005; received in revised form 9 February 2006; accepted 14 February 2006

Abstract

This study investigated the language learning strategy use of 55 ESL students with diering cultural and linguistic backgrounds enrolled in a college Intensive English Program (IEP). The IEP is a

language learning institute for pre-admissions university ESL students, and is an important step in

developing not only students basic Interpersonal Communications Skills (BICS), but more importantly their Cognitive Academic Language Prociency (CALP). Prociency with academic English is

a key contributor to students success in learning in their second language. Using the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the study examines the relationship between language learning

strategy use and second language prociency, focusing on dierences in strategy use across gender

and nationality. The study found a curvilinear relationship between strategy use and English prociency, revealing that students in the intermediate level reported more use of learning strategies than

beginning and advanced levels. More strategic language learners advance along the prociency continuum faster than less strategic ones. The study found that the students preferred to use metacognitive strategies most, whereas they showed the least use of aective and memory strategies. Females

tended to use aective and social strategies more frequently than males. Conclusions and pedagogical implications of the ndings are discussed.

2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Keywords: Language learning strategies; English as a second language; Intensive English learning; Measurement

of learning strategies; Strategy inventory for language learning (SILL); Cognitive academic language prociency

(CALP)

Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 940 565 3397x565 4403; fax: +1 940 565 4952.

E-mail addresses: ksh0030@unt.edu (K. Hong-Nam), leavell@unt.edu (A.G. Leavell).

0346-251X/$ - see front matter 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

doi:10.1016/j.system.2006.02.002

400

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

1. Introduction

Increased interest in student-centered learning approaches amongst language educators

has led to numerous studies investigating individual language learning strategies (LLS)

and their relationship to achievement in learning second/foreign languages. Studies have

indicated support for appropriately applied language learning strategies on second/foreign

language achievement (Bremner, 1998; Green and Oxford, 1995; Griths and Parr, 2001;

Mansanares and Russo, 1985; Oxford, 1990; Oxford and Ehrman, 1995; Oxford and Nyikos, 1989; Park, 1997; Politzer, 1983; Wharton, 2000). The consensus of the research is

that although all learners, regardless of success with language learning, consciously or

unconsciously employ a variety of learning strategies; successful language learners engage

in more purposeful language learning and use more language-learning strategies than do

less successful ones. Overall, ndings indicate that both the frequency with which learners

apply language learning strategies and the strategies they choose are distinguishing characteristics between more successful and less successful learners.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Language learning strategies

Research in the eld of learning strategies has dened language learning strategies as

. . .strategies that contribute to the development of the language system which the learner

constructs and (which) aect learning directly (Rubin, 1987, p. 23). Oxford (1990) further

described language learning strategies as steps taken to facilitate the acquisition, storage,

retrieval, and use of information. OMalley and Chamot (1990) viewed learning strategies

as the special thoughts or behaviors that individuals use to help them comprehend, learn,

or retain new information (p. 1). Holec (1981) argued that learning strategies can foster

learners autonomy in language learning. Strategies can also assist learners in promoting

their own achievement in language prociency (Bremner, 1998; Green and Oxford,

1995; OMalley et al., 1985; Oxford, 1990; Politzer, 1983). Learning strategies, therefore,

not only help learners become ecient in learning and using a language, but also contribute to increasing learners self-directed learning.

2.2. Studies on language learning strategies

Early research into language learning strategies was mostly concerned with investigating what language learning strategies learners used, without attempting to address the

links between strategy use and success (e.g., Rubin, 1987; Stern, 1975; Wenden, 1987).

Recent research has focused on determining the connections between strategy use and

language prociency (Green and Oxford, 1995; Oxford and Ehrman, 1995; Park, 1997;

Shmais, 2003). Such studies have shown that procient language learners employed more

strategies in language learning than less procient language learners. For instance, Green

and Oxford (1995) investigated the use of learning strategies of university students in

Puerto Rico and reported that the successful language learners engaged in more frequent

and higher levels of strategy use than less successful learners. A study of Korean university students (Park, 1997) revealed a positive linear relationship between strategy use and

language prociency when prociency was measured using the Test of English as a

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

401

Foreign Language (TOEFL) scores. Other ndings have exposed a relationship between

students perceptions of their language prociency and strategy use. Oxford and Nyikos

(1989) armed that greater strategy use accompanied perceptions of higher prociency,

while Wharton (2000) demonstrated a signicant correlation between the two factors,

indicating the higher a students language prociency self-rating, the more frequent strategy use was.

Studies have established a great deal of evidence of gender dierences in the use of language learning strategies. The results have usually favored females as more frequent users

of strategies (Ehrman and Oxford, 1989; Green and Oxford, 1995; Oxford, 1993). When

looking at the types of strategy use, females show more use of social learning strategies

(Politzer, 1983; Ehrman and Oxford, 1989), more frequent use of formal rule-based practice strategies, and conversational or input strategies (Oxford and Nyikos, 1989). Gender

dierences appear most evident in the use of socially based strategies such as group learning. However, gender dierence ndings in favor of greater strategy use by females may be

tempered by the context and/or culture of the language learning. For example, in a study

of adult Vietnamese refugees Tran (1988) found that males were more likely to use a variety of learning strategies than females. Refugees are a population typically characterized

by survival learning wherein men would be highly motivated to learn English for survival needs (e.g., supporting their family in the new society). Bilingual college students

in Singapore evidenced no statistically signicant gender eect in their reported strategy

use (Wharton, 2000). This may be attributable to an overall superiority in language learning ability and expertise on the part of bilingual students which may have equalized any

potential gender dierences in strategy use.

Cultural background (sometimes referred to as ethnicity or nationality) has been linked

to use and choice of language learning strategies (Bedell and Oxford, 1996; Grainger, 1997;

Oxford and Burry-Stock, 1995; Politzer, 1983; Reid, 1987; Wharton, 2000). Politzer (1983)

found that Hispanics used more social, interactive strategies, while Asian groups educated

in traditionally didactic settings chose memorization strategies. Wharton (2000) found

that bilingual Asian students learning a third language (English) favored social strategies

more than any other types. Culturally-specic strategy use may be a by-product of instructional approaches favored by specic cultural groups as opposed to inherent predispositions based on nationality or ethnicity of the individual. For instance, students educated

in the environments of lecture- and textbook-centered teaching approach(es) may use different strategies compared to students trained in student-centered contexts. Because language is so culturally situated (Garcia, 2005), it is dicult to parse out whether

dierences between groups are a result of dierences in instructional delivery, socio-cultural elements, or other culturally specic factors.

3. Purpose of the study

There is little in the extant literature which focuses specically on the language learning

strategies of students learning English in the context of Intensive English Programs (IEPs)

at the university level. The IEP course is a vital step in developing students Cognitive Academic Language Prociency (CALP) (Cummins, 1979), which is receiving increasing attention as a contributing factor to learners academic success. Therefore, this study

investigated the overall language learning strategy use of English learners enrolled in a university IEP, looked at the relationship between language learning strategy use and second

402

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

language prociency, and assessed any dierences in strategy use by gender and

nationality.

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

Fifty-ve ESL students enrolled in an IEP at a large Southwestern university participated in this study. When ranked by class level based on tested prociency with English

there were 11 Beginning, 30 Intermediate, and 14 Advanced learners. The age of the students ranged from 18 to 40 (M = 22). The sample was fairly balanced across males

(n = 25) and females (n = 30). The participants were from various countries (Brazil,

China, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and Togo), representing 10 dierent languages. Japanese was the largest original-language group of the

sample (40%), followed by Taiwanese (22%). The third largest language group was Korean

(20%), and the remaining groups comprised 18% of the sample (see Table 1).

The IEP is a language learning institute for pre-admissions university ESL students.

The participants reported having studied English in this IEP for total periods of time ranging from at least one month to one and a half years. The students years of formal English

instruction (i.e., English learned in any academic setting) ranged from 1 to 10. The majority of the participants were learning English to seek higher education or to earn a degree

after completion of the IEP. In the beginning of the program, a placement test was given

to all students, and they were placed in one of six English prociency levels from Level 1

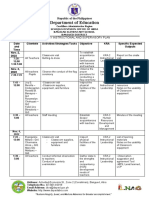

Table 1

Demographic description of participants

n

English prociency

Beginning

Intermediate

Advanced

11

30

14

20.0

54.5

25.5

Gender

Male

Female

25

30

45.5

54.5

Self-rated English prociency

Beginning

Intermediate

Advanced

17

31

7

30.9

56.4

12.7

Nationality

Japan

Taiwan

Korea

China

Indonesia

German

Brazil

Malaysia

Togo

Thai

22

12

11

3

2

1

1

1

1

1

40.0

22.0

20.0

5.5

3.6

1.8

1.8

1.8

1.8

1.8

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

403

(Beginning) to Level 6 (Advanced) according to the results of the language screening

admissions testing. The test assesses listening, speaking, reading, grammar, and composition. IEP learners engage in some form of language instruction in English for 45 hours

daily in the classroom. Students may also take advantage of the language learning lab

at their convenience.

4.2. Instruments

The Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL version 7.0 for ESL/EFL learners, 50 items), a self-report questionnaire, was used to assess the frequency of use of language learning strategies (Oxford, 1990). The SILL has been employed as a key instrument

in numerous studies. Studies have reported reliability coecients for the SILL ranging

from .85 to .98 making it a trusted measure for gauging students reported language learning strategy use (Bremner, 1998; Oxford and Burry-Stock, 1995; Park, 1997; Sheorey,

1999; Wharton, 2000). A Cronbachs a calculated for this study also revealed an acceptable reliability (.67). In the SILL, language learning strategies are grouped into six categories for assessment: Memory strategies for storing and retrieving information, Cognitive

strategies for understanding and producing the language, Compensation strategies for

overcoming limitations in language learning, Metacognitive strategies for planning and

monitoring learning, Aective strategies for controlling emotions, motivation, and Social

strategies for cooperating with others in language learning.

The SILL uses ve Likert-type responses for each strategy item ranging from 1 to 5 (i.e.,

from never or almost never true of me to always true of me). In this study, learners were

asked to respond to each item based on an honest assessment of their language learning

strategy use. Once completed, the SILL data furnishes a composite score for each category

of strategy. A reporting scale can be used to tell teachers and students which groups of

strategies they use the most in learning English: (1) High Usage (3.55.0), (2) Medium

Usage (2.53.4), and (3) Low Usage (1.02.4). Scale ranges were developed by Oxford

(1990).

An Individual Background Questionnaire (IBQ) was created by the researchers and was

distributed to collect demographic information about the students. Information collected

included nationality, home language, years of English study, time in the United States, and

time in the IEP. Participants were also asked to rate their English prociency (see Appendix A for the IBQ).

4.3. Data collection and analysis

The SILL was administrated to ESL students by the classroom teacher during a regular class period. The full descriptive instructions regarding the procedures of administration were provided to and discussed with the instructor of the classes before the

administration. The students were told that there were no right or wrong answers to

any question and that their condentiality was secured and their response would be used

for research purposes only. They were also informed that while their participation would

not aect their grades, they still had the option not to participate. All students chose to

ll out the surveys.

Data analyses included the computation of descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation, and frequencies) to compile information about demographics of the participants

404

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

and to calculate overall strategy use. In order to determine any variation in strategy use

relative to English prociency, gender, and nationality, an analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted using these factors as independent variables and the six categories of strategies as dependent variables. The Schee post-hoc test was used to nd where any significant dierences in strategy use lay.

5. Results

5.1. Overall strategy use

A one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically signicant dierences

(F = 20.79, p = 0.00) in the overall use of strategies by participants (see Table 2). Specifically, the results of the Schee post-hoc test revealed a statistically signicant dierence in

the use of memory and aective strategies compared to cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, or social strategies. These four categories ranked high in use (M = 3.45.0). The

least preferred strategies were aective (M = 3.02) and memory (M = 3.04). The most preferred group of the six strategy categories for participants was metacognitive strategies

(M = 3.66) followed by social strategies (M = 3.62), compensation strategies,

(M = 3.59), and cognitive strategies (M = 3.44).

Table 3 ranks reported strategy use by individual item mean scores on the SILL for the

entire sample; results are presented in descending order from most to least used. The most

used strategy by participants was a compensation strategy, When I cant think of a word

during a conversation in English, I use gestures (M = 4.25). The least used item for the participants (and the only one that fell within the Low usage range of 1.02.4) was aective, I

notice if I am tense or nervous when I am studying or using English (M = 1.76).

5.2. Use of the strategies by English prociency

When participant data was grouped by tested English prociency (Beginning, Intermediate, or Advanced Level) data analysis revealed statistically signicant dierences for the

use of compensation strategies. (A summary of the ANOVA results for the use of six categories of strategies by English prociency is shown in Table 4.) Compensation strategies

were used more by the Intermediate level participants than the Advanced level (F = 5.04,

p = 0.01). The most preferred strategy category for students in Beginning and IntermediTable 2

Descriptive statistics for the variables and F-tests for main dierence between the six strategy categories

Variable

Mean

SD

Minimum

Maximum

Rank

Signicance

Dierence*

Memory

Cognitive

Compensation

Metacognitive

Aective

Social

Total

3.04

3.44

3.59

3.66

3.02

3.62

3.40

0.42

0.43

0.49

0.48

0.53

0.51

0.55

2.00

2.64

2.50

2.56

1.67

2.33

1.67

4.22

4.71

4.67

4.67

4.33

5.00

5.00

5

4

3

1

6

2

20.79

0.00

Mem, A < Cog,

Com, Met, Soc

Mem (Memory strategies), Cog (Cognitive strategies), Com (Compensation strategies), Met (Metacognitive

strategies), A (Aective strategies), Soc (Social strategies).

*

p < 0.05.

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

405

Table 3

Preference of language learning strategies by ESL students

Strategy

category

Strategy

No.

Strategy

statement

High usage (M = 3.50 or above)

Com

25

When I cannot think of a word during

a conversation in English, I use gestures

A

44

I talk to someone else about

how I feel about learning English

Met

32

I pay attention when

someone is speaking English

Com

24

To understand unfamiliar

English words, I make guesses

Met

33

I try to nd out how to be

a better learner of English

Cog

12

I practice the sounds of English

Com

29

If I cant think of an English word,

I use a word or phrase that

means the same thing

Met

38

I think about my

progress in learning English

Cog

11

I try to talk like

native English speakers

Soc

48

I ask for help from English speakers

Met

31

I notice my English mistakes and use

that information to help me do better

Cog

15

I watch TV shows spoken in English or

go to movies spoken in English

A

39

I try to relax whenever

I feel afraid of using English

Cog

20

I try to nd patterns (grammar) in English

Soc

46

I ask English speakers to correct me when I talk

Met

37

I have clear goals for improving my English skills

Cog

14

I start conversations in English

Met

35

look for people I can talk to in English

Met

30

I try to nd as many ways as

I can to use my English

Soc

49

I ask questions in English

Soc

50

I try to learn about the

culture of English speakers

Cog

17

I write notes, messages,

letters or reports in English

Mem

1

I review English lessons often

Medium Usage (M = 2.53.4)

Cog

10

I say or write new

English words several times

Soc

47

I practice English with other students

Mem

2

I use new English words in a sentence

so I can remember them

Mem

3

I connect the sound of a new

English word and an image or

picture of the word to

help me remember the word

Rank

Mean

4.25

4.16

4.13

4.05

4.02

6

7

3.98

3.95

3.89

3.84

10

11

3.84

3.82

12

3.78

13

3.78

14

15

16

17

18

19

3.67

3.67

3.64

3.60

3.60

3.58

20

21

3.56

3.56

22

3.51

23

3.50

24

3.45

25

26

3.42

3.40

27

3.40

(continued on next page)

406

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

Table 3 (continued)

Strategy

category

Strategy

No.

Strategy

statement

Rank

Mean

Cog

19

28

3.40

Cog

18

29

3.38

Cog

21

30

3.29

Cog

Met

13

36

31

32

3.27

3.24

41

33

3.24

Mem

Com

Com

4

27

28

34

35

36

3.20

3.18

3.15

A

Soc

43

45

37

38

3.09

3.09

Met

34

39

3.04

Cog

Cog

Mem

16

22

8

40

41

42

3.02

3.02

3.00

Com

26

43

2.98

Cog

23

44

2.95

Mem

I look for words in my own language that

are similar to new words in English

I rst skim (read over the passage quickly) an

English passage then go back and read carefully

I nd the meaning of an English word by

dividing it into parts that I understand

I use the English words I know in dierent ways

I look for opportunities to read

as much as possible in English

I give myself a reward or treat

when I do well in English

I use ashcards to remember new English words

I read English without looking up every new word

I try to guess what the other

person will say next in English

I write down my feelings in a language learning diary

If I do not understand something in English,

I ask the other person to slow down or say it again

I plan my schedule so I will have

enough time to study English

I read for pleasure in English

I try not to translate word-for-word

I make connection between what

I already know and new things I learn in English

I make up new words if I do not

know the right ones in English

I make summaries of information

that I hear or read in English

I remember new English words by

remembering their location on the page,

on the board, or on a street sign

I encourage myself to speak English

even when I am afraid of making a mistake

I physically act out new English words

I use rhymes to remember new English words

I remember a new English word by imagining

(mental picture) a situation in which the word might be used

45

2.90

46

2.82

47

48

49

2.80

2.70

2.50

50

1.76

A

Mem

Mem

Mem

40

7

5

6

Low Usage (M = 2.4 or below)

A

42

I notice if I am tense or nervous

when I am studying or using English

Mem (Memory strategies), Cog (Cognitive strategies), Com (Compensation strategies), Met (Metacognitive

strategies), A (Aective strategies), Soc (Social strategies).

ate levels were metacognitive strategies (M = 3.51 and M = 3.77, respectively). The most

frequently used strategies for the Advanced group were social strategies, (M = 3.67). The

least preferred categories for Beginning and Intermediate groups were aective strategies

(M = 3.21 and M = 2.92, respectively), and for Advanced and Beginning levels were memory strategies, (M = 2.97 and M = 3.21, respectively).

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

407

Table 4

Summary of variation in use of strategy categories by English prociency (Level)

Variables

Beginning

Intermediate

Advanced

Signicance

Dierence*

Adv < Int

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mem

Cog

Com

Met

A

Soc

3.21

3.41

3.40

3.51

3.21

3.39

0.40

0.42

0.49

0.45

0.58

0.59

3.01

3.49

3.76

3.77

2.92

3.69

0.39

0.48

0.50

0.38

0.53

0.46

2.97

3.37

3.37

3.55

3.07

3.67

0.48

0.33

0.30

0.65

0.46

0.54

1.22

0.43

5.04

1.79

1.32

1.44

0.31

0.66

0.01

0.18

0.28

0.25

Total

3.35

0.49

3.44

0.57

3.33

0.52

1.46

0.23

Mem (Memory strategies), Cog (Cognitive strategies), Com (Compensation strategies), Met (Metacognitive

strategies), A (Aective strategies), Soc (Social strategies), Adv = Advanced, Int = Intermediate.

*

p < 0.05.

5.3. Use of the strategies by gender

Table 5 shows results for the use of language learning strategies when participants were

grouped by gender. Although the dierence in overall strategy use between male and

female students was not statistically signicant, a statistically signicant dierence in the

use of aective strategies was found between males and females (F = 3.98, p = 0.05), with

females reporting higher use of aective strategies. Mean dierences revealed that females

(M = 3.45) engaged in strategy use more frequently than males (M = 3.34). Males favored

the use of metacognitive (M = 3.65) and compensation strategies (M = 3.62) most, and

aective strategies the least (M = 2.87). Female participants reported using social

(M = 3.70) and metacognitive strategies (M = 3.67) most and memory strategies the least

(M = 3.06).

5.4. Use of the strategies by nationality

As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were from Japan, Taiwan, Korea, or

China (87.5%). Because some nationalities had very low representation, certain subgroups

were combined in order to evaluate statistically possible dierences in strategy use by

Table 5

Summary of variation in use of strategy categories by gender

F

Signicance

Dierence*

0.46

0.44

0.48

0.46

0.50

0.53

0.15

2.73

0.13

0.03

3.98

1.25

0.70

0.10

0.72

0.87

0.05

0.27

M<F

0.54

3.13

0.08

Variables

Male

Female

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mem

Cog

Com

Met

A

Soc

3.01

3.34

3.62

3.65

2.87

3.54

0.37

0.39

0.51

0.52

0.53

0.49

3.06

3.53

3.57

3.67

3.14

3.70

Total

3.34

0.55

3.45

Mem (Memory strategies), Cog (Cognitive strategies), Com (Compensation strategies), Met (Metacognitive

strategies), A (Aective strategies), Soc (Social strategies), M = male, F = female.

*

p < 0.05.

408

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

Table 6

Summary of variation in use of strategy categories by nationality

Chinese

(n = 15)

Korean

(n = 11)

Signicance

Dierence*

0.43

0.40

0.69

0.59

0.48

0.56

0.42

0.91

1.50

4.35

1.87

1.22

0.74

0.44

0.23

0.01

0.15

0.31

C < J,O

0.59

1.85

0.15

Variables

Japanese

(n = 22)

Others

(n = 7)

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mem

Cog

Com

Met

A

Soc

3.00

3.45

3.67

3.80

2.86

3.62

0.48

0.38

0.43

0.35

0.56

0.39

3.00

3.50

3.58

3.39

3.00

3.78

0.27

0.49

0.48

0.40

0.47

0.62

3.08

3.26

3.35

3.53

3.29

3.39

0.48

0.46

0.44

0.57

0.50

0.54

3.19

3.56

3.79

4.02

3.14

3.67

Total

3.40

0.55

3.37

0.54

3.32

0.50

3.56

Mem (Memory strategies), Cog (Cognitive strategies), Com (Compensation strategies), Met (Metacognitive

strategies), A (Aective strategies), Soc (Social strategies), C = Chinese, J = Japanese, O = Others.

*

p < 0.05.

nationality. Because of the similarities between languages spoken in China and Taiwan

these groups were combined under the category Chinese. Additionally, the small

remaining number of students from other countries (n = 7), were grouped as Other.

The ultimate grouping by nationality was: Japanese (n = 22), Chinese (n = 15), Korean

(n = 11), and Other (n = 7).

As Table 6 shows, all participants engaged in active use of strategies in language learning regardless of their nationalities. ANOVA results revealed a statistically signicant difference in the use of metacognitive strategies for Japanese over Other (F = 4.35, p = 0.01)

Participants from Japan, Korea, and Other reported using use metacognitive strategies

most (M = 3.80, M = 3.53, and M = 4.02, respectively), while Chinese students preferred

to use social strategies most (M = 3.78). Aective strategies were least selected by Japanese

students (M = 2.86) and Other (M = 3.14), whereas the Korean group showed the least

use of memory strategies (M = 3.08). Chinese students reported the lowest use of both

memory and aective strategies (M = 3.00).

6. Discussion

6.1. Overall strategy use

When considered as one group, these second language learners reported using metacognitive and social strategies more frequently than any other strategy during their language

learning. ESL students in the IEP appeared familiar with the need to manage their learning

processes and indicated they were in control of planning, organizing, focusing, and evaluating their own learning, behaviors inherent in most denitions of metacognition (Borkowski et al., 1987).

The intensive learning environment of the IEP program may be a prime contributor

in several ways to the preferred use and selection of both metacognitive and social

strategies. In terms of metacognitive strategies, learners enrolled in intensive English

programs typically have a strong instrumental motivation for learning English. Unlike

learners who might enroll in a foreign language for fun or self-advancement or because

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

409

a language course is required (what Diab (2000) refers to as integrative reasons), IEP

students are learning English to advance their academic and professional lives. The

(self-imposed) threat of failing the program is a huge motivator for taking control

of their learning. The sooner they graduate the program (which can only be accomplished by achieving adequate scores on the Test of English as a Foreign Language

(TOEFL)) the sooner they can begin taking regular university coursework. Ecient

planning and self-monitoring of ones learning progress (both metacognitive behaviors)

by the student are instrumental in achieving their goal of completion. Metacognitive

knowledge and increases in academic performance go hand in hand (Pintrich and Garcia, 1994).

The IEP may also play a role in high use of social strategies by participants, many

of whom showed a strong preference for learning with others by asking questions and

cooperating with peers. This particular IEP has a very student-oriented philosophy

underpinning its curriculum. In terms of the participants high social strategy use,

which is a departure in some ways from culturally driven learning practices that are

more independent, the environment (e.g., high availability of native-English speakers

around the students) of and instruction in the IEP strongly encourage and support

more interactive learning for the sake of developing greater linguistic uency. These

ndings are in line with those of Phillips (1991) study of Asian ESL students also

enrolled in college IEPs who used social strategies more than aective and memory

strategies.

The least favored strategies by participants in this study were aective strategies and

memory strategies. In terms of aect, these learners reported that despite eorts to relax

when they were uncertain about speaking English, their fears of making a mistake often

kept them from trying. Asian cultural mores encourage listening to others and discourage

public discussion of feelings. As the majority of the students participating in this investigation were Asian, their upbringing and previous school experiences may have impacted

their behavior in this area (Politzer, 1983; Reid, 1987).

Low use of memory strategies was initially surprising in that these are largely in keeping

with instructional delivery systems typically employed in many Asian countries which are

frequently didactic and emphasize rote memorization. However, further examination of

the literature revealed that other studies have also had contradictory ndings to this perhaps too common assumption that Asian students have strong preferences for memory

strategies rather than communicative strategies such as working with others, asking for

help, and cooperating with peers (Al-Otaibi, 2004; Bremner, 1998; Politzer and McGroarty, 1985; Wharton, 2000; Yang, 1999).

Again the impact of the IEP training might have inuenced changes in student strategy preferences. Another possibility is that memory strategies can be dened dierently

in dierent studies. Politzer and McGroarty (1985) found strong preferences for ESL

learners for using memory strategies. They dened memory strategies as rote-memorization of words, phrases, and sentences. By contrast, the least used memory strategies in

the SILL for the current study were not related whatsoever to rote memorization, rather

they were things like acting out new vocabulary, using rhymes, and creating a mental or

spatial image. It is possible these were less popular with adult learners and thus not

used as much or at all. Memory strategies that did rank higher were those such as

reviewing English lessons frequently, and using words in sentences, more traditional

study skills.

410

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

6.2. Strategy use by English prociency

While prociency level does not necessarily equate with amount of language learning

(i.e., number of years), more experienced language learners have been shown to use more

strategies (Bremner, 1998; Green and Oxford, 1995; Oxford and Burry-Stock, 1995; Park,

1997; Sheorey, 1999; Wharton, 2000). Research examining strategy use and English prociency of ESL students has shown a positive linear relationship between the two factors

(Bremner, 1998; Green and Oxford, 1995; Oxford and Nyikos, 1989; Wharton, 2000).

However, the current study found that when students were grouped by both tested and

self-rated English prociency, the students at the intermediate level reported using more

overall strategies than beginners or advanced language learners. Only one other study (Phillips, 1991) also showed this curvilinear relationship between strategy use and language

prociency.

In order to shed light on this unexpected nding, we turned to the extant literature on

how strategic learning abilities develop along the continuum from novice learner to expert.

In their classic work on strategic reading, Paris et al. (1994) identied three kinds of

knowledge acquired as learners progress from novice to expert: declarative knowledge,

procedural knowledge and conditional knowledge. Declarative knowledge is described

as knowledge about learning tasks (i.e., I know that speaking English and writing English

require dierent types of grammar) and personal abilities (i.e., I am good at speaking English). Procedural knowledge is knowledge about how to learn. Knowing how to scan text

for answers to objective questions, knowing how to make inferences from text, and knowing how to summarize are examples of procedural knowledge. While both of these types of

knowledge are necessary to move a learner along the continuum from novice to expert,

they alone are not enough. A third type of knowledge, conditional knowledge, completes

the triarchy of strategic learning by allowing the reader or learner to orchestrate his or her

learning by choosing the correct strategy for the correct task.

Using our understanding of these three types of strategic knowledge as a window

through which to view the ndings regarding prociency and strategy use, the following

explanation seems plausible. Beginning L2 learners may possess little in the way of declarative knowledge regarding their second language learning, much less conditional knowledge about how to eectively apply learning strategies (Phillips, 1991). However,

intermediate level learners have reached a point in their learning where they have gained

enough vocabulary and competence with the L2, along with some procedural knowledge

to be able to step back and reect on how eectively their learning process is working. Such

reection is a primary characteristic of learners who are able to move beyond the basic levels of memorizing vocabulary and grammar structures. As learners engage in more active

management of their language learning strategy choices and out the ways of learning that

are best for them, their heightened level of awareness means they are very conscious of how

they are learning. It would follow that they would report more strategy use.

For the advanced learners, the results indicate that once language learners reach this

high level of language prociency, their need to consciously administer and deliberate

about their learning choices becomes less necessary. Their learning process becomes more

intrinsic and is so well established they need only be conscious of their process if they are

confronted with a very dicult or novel learning task. Carl Bereiter (1995) describes this

internalization as resulting from the deepest and most thorough understanding (p. 23),

whereby the process becomes so incorporated into the way we perceive the world and

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

411

comprehend communications . . . [we] should not have to remember to transfer the learning, but experience it automatically (p. 24). Advanced learners habitual and successful

application of language strategies may be so internalized that they do not report what has

become for them an automated process, thus their strategy use appears to be lower than

that of the intermediate group.

It was interesting to note that students in advanced levels used social strategies more

than any other levels. With increased prociency came increased condence, allowing

the learners to interact with others by practicing their language knowledge to promote

communicative skills. The high sense of condence in learning English is likely to encourage students to use various strategies with more emphasis on the use of social and functional practice strategies (Horwitz, 1987; Siebert, 2003; Yang, 1999).

6.3. Strategy use by gender

Much research has shown that females tend to use more learning strategies than males

(Ehrman and Oxford, 1989; Oxford, 1990; Oxford and Ehrman, 1995; Politzer, 1983;

Oxford and Nyikos, 1989; Green and Oxford, 1995). The ndings of this study bear this

out. There was a statistically signicant dierence in aective strategy use by females.

(Women also used social strategies more according to mean dierences; however, there

was no statistical signicance). Women tend to build relationships and use social networks

with greater consistency than men. Thus, this use of emotional and social support systems

in the context of language learning is not unexpected.

6.4. Strategy use by nationality

Several studies have found that cultural background is related to language strategy use

(Bedell and Oxford, 1996; Grainger, 1997; Oxford and Burry-Stock, 1995; Politzer, 1983;

Reid, 1987; Wharton, 2000). However, culture as a construct is incredibly complex. As

Oxford (1990) has stressed, it would be impossible (and undesirable) to try to attribute

one particular language learning approach to a specic cultural group. The only statistically

signicant dierence was in the use of metacognitive strategies by Japanese and Others.

Mean dierences did indicate certain preferences by nationality groups, i.e., Chinese students favored social strategies while all others favored metacognitive. Since over 87% of this

studys sample is Asian, it is tempting to want to embrace a popular belief about frequent use

of strategies like rote-memorization by Asian students. Nevertheless, ndings of this study

and others reject this assumption (Phillips, 1991; Sheorey, 1999; Yang, 1999; Wharton,

2000). Educators should be mindful that there are individual dierences among students

regardless of socio-cultural, educational, and other aspects of individual backgrounds.

7. Conclusion and implications

This study showed that English language learners enrolled in an intensive English program were clearly aware that learning strategies were a part of their language learning process. Strategy use reported by these learners indicated a high preference for metacognitive

strategies which helped them in directing, organizing, and planning their language learning

(metacognitive strategies). The teacher of these students can facilitate learning by addressing both content and process. For example, instead of handing out a simple list of 40

412

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

vocabulary words, the teacher can organize the terms in groups based on a unifying concept for each group. The teacher should also take a few minutes to tell students how and

why the terms are organized as they are and how the graphic organization of the terms can

have a positive impact on their understanding. This explicit attention to building strategic

awareness in learners has been shown to be quite successful in enhancing their skills as

learners (Keene and Zimmermann, 1997).

Diculty in dealing with anxiety related to language learning was reported by most

participants. The women in the current study appeared to utilize their social networks

as a means of support. While male participants apparently did not prefer to talk to their

peers about their feelings, students might benet from an opportunity to journal for a few

minutes at the end of each learning session as to how they felt about class and their performance on that day. This may help students express feelings in a more private way, and

recognize how those feelings may have impacted the days learning. In addition, as trust is

built between teacher and student, the instructor may request access to journal entries

which would provide an additional source of information useful in mediating students

progress.

Last, the nding that learners at the intermediate level report more strategy use than

beginners or advanced students indicates that learners at dierent levels have dierent

needs in terms of teacher intervention in the learning process. For beginning learners,

the teacher needs to be explicit in developing declarative and procedural knowledge that

helps heighten understanding of the what and how of successful language learning. This

metacognitive awareness of how students can control and positively impact their language

learning must be supported until the crucial element of conditional knowledge is in place;

only then can learners reach independence in their language learning.

Relating daily learning tasks to students prior knowledge of how they learn best is very

important. Beginning language learners tend to be more passive due to shyness or lack of

vocabulary. In terms of content, the teachers role would be to increase vocabulary and

perhaps to introduce simple conversation opportunities as early as possible to build condence and uency. Eective teachers should consider each learning task from a novices

perspective and scaold the learning process through purposeful strategy choices. He or

she can use the strategy as an instructional technique and be sure to discuss with students

why one particular approach may be a better way to learn. For example, in introducing a

verb or group of verbs that involves actions, (to talk, to sit, to run) the teacher might demonstrate the actions (Total Physical Response) during the lesson and then talk to students

about the value of acting out (or at least visualizing) the action of the verb.

For intermediate students, the teachers role changes with the understanding that these

students have a growing body of strategic knowledge, along with a fair amount of content

(i.e., vocabulary, grammar, etc.). The task these learners face is how to select the right

strategies for specic learning tasks and for themselves as individuals. The teacher must

be cautious about imposing his or her own learning style upon the students; thus, the conversation around the learning should include questions like, What might be some dierent ways to approach this task, and which of those would work best for you? Selfreection is crucial here. The teacher should be prepared to give suggestions, but must also

allow students to make their own choices.

This is even truer for the advanced learners. The teacher must realize that they are

becoming autonomous in their ability to guide their learning and the teachers role shifts

from mediator to facilitator. If the teacher sees the student struggling, then he or she

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

413

should intervene with assistance. At this advanced level, the teacher should step back and

let the student lead the way in terms of how he or she approaches the language learning

task. The teacher should consider the learning task in terms of what the student will be

able to accomplish independently before needing the teachers assistance. For example,

can students work in pairs or a small group to create a dialogue using the vocabulary

and grammar for the day? Then the teacher monitors their progress. The groups subsequently share their dialogue and the class assists in any changes or corrections. If the teacher is careful about ensuring students are prepared for such tasks, the activities can build

condence and greater independence for all language learners.

Appendix A. Individual background questionnaire

Please choose (only one) or write the most appropriate answer to you after reading each

statement.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Age _____________________

Sex: Male _______ Female _______

Nationality _____________________________________________________

Level of your communication class 1 2 3 4 5 6

Language(s) you usually speak at home ________________________________

Language(s) you usually speak with your friends _____________________________

How long have you been studying English as second/foreign language in a formal

setting (school)? ____________________________________________

8. How long have you been in the Unites States? _______________________________

9. How long have you been studying English at IELI? ___________________________

10. What do you think is your level of English prociency?

Beginning

Intermediate

Advanced

References

Al-Otaibi, G.N., 2004. Language learning strategy use among Saudi EFL students and its relationship to

language prociency level, gender and motivation. Doctoral Dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania,

Indiana, PA.

Bedell, D., Oxford, R.L., 1996. Cross-cultural comparisons of language strategies in the Peoples Republic of

China and other countries. In: Oxford, R. (Ed.), Language Learning Strategies around the World: CrossCultural Perspectives. University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, pp. 4760.

Bereiter, C., 1995. A dispositional view of transfer. In: McKeough, A., Lupart, J., Marini, A. (Eds.), Teaching for

Transfer: Fostering Generalization in Learning. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 2134.

Borkowski, J.G., Carr, M., Pressley, M., 1987. Spontaneous strategy use: Perspectives from metacognitive theory.

Intelligence 11, 6167.

Bremner, S., 1998. Language learning strategies and language prociency: Investigating the relationship in Hong

Kong. Asian Pacic Journal of Language in Education 1 (2), 490514.

Cummins, J., 1979. Cognitive/academic language prociency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age

question and some other matters. Working Papers on Bilingualism 19, 121129.

Diab, R.L., 2000. Political and socio-cultural factors in foreign language education: the case of Lebanon. Texas

papers in Foreign Language education 5, 177187.

Ehrman, M., Oxford, R.L., 1989. Eects of sex dierences, career choice, and psychological type on adult

language learning strategies. Modern Language Journal 73, 113.

414

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

Garcia, E.E., 2005. Teaching and Learning in Two Languages: Bilingualism and Schooling in the United States.

Teachers College Press, New York.

Grainger, P.R., 1997. Language-learning strategies for learners of Japanese: Investigating ethnicity. Foreign

Language Annals 30 (3), 378385.

Green, J., Oxford, R.L., 1995. A closer look at learning strategies, L2 prociency, and gender. TESOL Quarterly

29 (2), 261297.

Griths, C., Parr, J.M., 2001. Language-learning strategies: Theory and perception. ELT Journal 53 (3), 247

254.

Holec, H., 1981. Autonomy and Foreign Language Learning. Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Horwitz, E.K., 1987. Surveying student beliefs about language learning. In: Wenden, A., Rubin, J. (Eds.),

Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Prentice/Hall International, Englewood Clis, NJ, pp. 119129.

Keene, E.O., Zimmermann, S., 1997. Mosaic of Thought. Heinemann, Portmouth, NH.

Mansanares, L.K., Russo, R.P., 1985. Language learning: Learning strategies used by beginning and intermediate

ESL students. Language Learning 35 (1), 2142.

OMalley, J., Chamot, A., 1990. Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

OMalley, J.M., Chamot, A.U., Stewner-Manzanares, G., Russo, R.P., Kupper, L., 1985. Learning strategy

application with students of English as a second language. TESOL Quarterly 19 (3), 557584.

Oxford, R.L., 1990. Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. Heinle and Heinle,

Boston, MA.

Oxford, R.L., 1993. Instructional implications of gender dierence in language learning styles and strategies.

Applied Language Learning 4, 6594.

Oxford, R.L., Burry-Stock, J., 1995. Assessing the use of language learning strategies worldwide with the ESL/

EFL version of the strategy inventory of language learning (SILL). System 23 (1), 123.

Oxford, R.L., Ehrman, M., 1995. Adults language learning strategies in an intensive foreign language program in

the United States. System 23 (3), 359386.

Oxford, R.L., Nyikos, M., 1989. Variables aecting choice of language learning strategies by university students.

The Modern Language Journal 73 (3), 291300.

Paris, S., Lipson, M., Wixson, K., 1994. Becoming a strategic reader. In: Ruddell, R., Ruddell, M., Singer, H.

(Eds.), Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, fourth ed. International Reading Association, Chicago,

pp. 788810.

Park, G.P., 1997. Language learning strategies and English prociency in Korean University. Foreign Language

Annals 30 (2), 211221.

Phillips, V., 1991. A look at learner strategy use and ESL prociency. CATESOL Journal (Nov), 5767.

Pintrich, P.R., Garcia, T., 1994. Self-regulated learning in college students: Knowledge, strategies, and

motivation. [On line]. Available from: http://ccwf.cc.utaxas.edu/~tgarcia/p&gpub94pl.html.

Politzer, R., 1983. An exploratory study of self-reported language learning behaviors and their relation to

achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 6, 5465.

Politzer, R., McGroarty, M., 1985. An exploratory study of learning behaviors and their relationship to gains in

linguistic and communicative competence. TESOL Quarterly 19, 103124.

Reid, J.M., 1987. The learning style preferences of ESL students. TESOL Quarterly 21, 87111.

Rubin, J., 1987. Learner strategies: Theoretical assumptions, research history and typology. In: Wenden, A.,

Rubin, J. (Eds.), Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Prentice/Hall International, Englewood Clis, NJ,

pp. 1530.

Sheorey, R., 1999. An examination of language learning strategy use in the setting of an indigenized variety of

English. System 27, 173190.

Shmais, W.A., 2003. Language learning strategy use in Palestine. TESL-EJ 7 (2), 117.

Siebert, L., 2003. Student and teacher beliefs about language learning. The ORTESOL Journal 21, 739.

Stern, H.H., 1975. What can we learn from the good language learner? Canadian Modern Language Review 31,

304318.

Tran, T.V., 1988. Sex dierences in English language acculturation and learning strategies among Vietnamese

adults aged 40 and over in the United States. Sex Roles 19, 747758.

Wenden, A., 1987. How to be a successful language learner: Insights and prescriptions from L2 learners. In:

Wenden, A., Rubin, J. (Eds.), Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Prentice/Hall International,

Englewood Clis, NJ, pp. 103118.

K. Hong-Nam, A.G. Leavell / System 34 (2006) 399415

415

Wharton, G., 2000. Language learning strategy use of bilingual foreign language learners in Singapore. Language

Learning 50 (2), 203243.

Yang, N.D., 1999. The relationship between EFL learners beliefs and learning strategy use. System 27, 515535.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Glenn WhartonDokumen16 halamanGlenn Whartonapi-3771376Belum ada peringkat

- Radwan Squ StrategiesMarch 2011 AarDokumen49 halamanRadwan Squ StrategiesMarch 2011 AarJoshi ThomasBelum ada peringkat

- Speaking Strategies Use of Grade Eleven Students at Leka Nekemte Preparatory School: Gender in FocusDokumen11 halamanSpeaking Strategies Use of Grade Eleven Students at Leka Nekemte Preparatory School: Gender in FocusFayisa FikaduBelum ada peringkat

- A Study of Language Learning Strategies Used by Applied English Major Students in University of TechnologyDokumen22 halamanA Study of Language Learning Strategies Used by Applied English Major Students in University of TechnologyYaming ChenBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategies and English Proficiency in Korean Univelsity StudentsDokumen11 halamanLanguage Learning Strategies and English Proficiency in Korean Univelsity StudentsSyahira MayadiBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategies of Successful ESL StudentsDokumen10 halamanLanguage Learning Strategies of Successful ESL StudentsJess YimBelum ada peringkat

- Metacognitive Language Learning Strategies Use, Gender, and Learning Achievement A Correlation StudyDokumen14 halamanMetacognitive Language Learning Strategies Use, Gender, and Learning Achievement A Correlation StudyIJ-ELTSBelum ada peringkat

- Magogwe (2007) The Relationship Between Language LearningDokumen15 halamanMagogwe (2007) The Relationship Between Language Learningmdazrien76Belum ada peringkat

- Ej1076687 PDFDokumen7 halamanEj1076687 PDFulfa putri andalasiaBelum ada peringkat

- PR1 Chapter 2Dokumen23 halamanPR1 Chapter 2jay michael0923 padojinogBelum ada peringkat

- 2015 - Language Learning Strategies in Chinese StudentsDokumen8 halaman2015 - Language Learning Strategies in Chinese StudentsDao Mai PhuongBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategies and English Proficiency: A Study of Chinese Undergraduate Programs in ThailandDokumen5 halamanLanguage Learning Strategies and English Proficiency: A Study of Chinese Undergraduate Programs in ThailandMuhammad Shofyan IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- LLS Journal ArticleDokumen10 halamanLLS Journal ArticleYomana ChandranBelum ada peringkat

- Foreign Language Anxiety and Strategy Use: A Study With Chinese Undergraduate EFL LearnersDokumen8 halamanForeign Language Anxiety and Strategy Use: A Study With Chinese Undergraduate EFL Learnersjeni evalitaBelum ada peringkat

- @strategies For Successful Learning in An English Speaking Environment Insights From A Case StudyDokumen25 halaman@strategies For Successful Learning in An English Speaking Environment Insights From A Case StudyMinh right here Not thereBelum ada peringkat

- Zhengdong GanDokumen16 halamanZhengdong Ganapi-3771376Belum ada peringkat

- Patani Malay & Southern Thai Speakers' Language Learning Strategies in Acquiring English CollocationsDokumen15 halamanPatani Malay & Southern Thai Speakers' Language Learning Strategies in Acquiring English CollocationsDanai JariBelum ada peringkat

- The Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsDokumen10 halamanThe Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsJoshua LagonoyBelum ada peringkat

- English Language Learning Strategies of Malaysian PDFDokumen7 halamanEnglish Language Learning Strategies of Malaysian PDFSharon Selvarani SelladuraiBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Language Learning Strategies: A Synthesis of Studies With Implications For Strategy TrainingDokumen13 halamanUse of Language Learning Strategies: A Synthesis of Studies With Implications For Strategy TrainingEduardo100% (1)

- Review of Related LiteratureDokumen3 halamanReview of Related Literatureciedelle arandaBelum ada peringkat

- Kafipour Descriptive CorrelationalDokumen23 halamanKafipour Descriptive CorrelationallitonhumayunBelum ada peringkat

- English VocabularyDokumen28 halamanEnglish VocabularyRima SadekBelum ada peringkat

- Direct IndirectDokumen42 halamanDirect IndirectJason CooperBelum ada peringkat

- Article Teacher Perception PracticeDokumen38 halamanArticle Teacher Perception PracticeUmaira Aleem RanaBelum ada peringkat

- Learning StrategiesDokumen22 halamanLearning StrategiesBE 005Belum ada peringkat

- Strategies For Better Learning of English Grammar: Chinese vs. ThaisDokumen16 halamanStrategies For Better Learning of English Grammar: Chinese vs. ThaisAndrés BertelBelum ada peringkat

- Learning StrategiesDokumen10 halamanLearning StrategiesMuuammadBelum ada peringkat

- Brief Reports and Summaries: Learning Strategies and Learning EnvironmentsDokumen6 halamanBrief Reports and Summaries: Learning Strategies and Learning EnvironmentsSharafee IshakBelum ada peringkat

- Concept Paper 3Dokumen6 halamanConcept Paper 3kimjhonmendez15Belum ada peringkat

- Manuscript - A Study On English Language Learning Strategy Use by University Students in KoreaDokumen23 halamanManuscript - A Study On English Language Learning Strategy Use by University Students in KoreaEric HallBelum ada peringkat

- Extroversión - Introversión y AprendizajeDokumen8 halamanExtroversión - Introversión y AprendizajeBetsi MartinBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Language Learning StrategiesDokumen13 halamanUse of Language Learning StrategiesMuftah HamedBelum ada peringkat

- Hearing Impaired LLSDokumen43 halamanHearing Impaired LLSWawa OzirBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategies Among EFL/ESL Learners: A Review of LiteratureDokumen8 halamanLanguage Learning Strategies Among EFL/ESL Learners: A Review of LiteratureAlpin MktBelum ada peringkat

- English Language Learning Strategies: Attend To From and Attend To Meaning Strategies (A Case Study at Sma Negeri 9 Makassar)Dokumen14 halamanEnglish Language Learning Strategies: Attend To From and Attend To Meaning Strategies (A Case Study at Sma Negeri 9 Makassar)Fiknii ZhaZhaBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategiesand English Proficiencyof Grade 12 StudentsDokumen7 halamanLanguage Learning Strategiesand English Proficiencyof Grade 12 Studentsnhatquangn33Belum ada peringkat

- A Comparison Between The Effectiveness of Mnemonic Versus Non-Mnemonic Strategies in Foreign Language Learning Context by Fatemeh Ahmadniay Motlagh & Naser RashidiDokumen8 halamanA Comparison Between The Effectiveness of Mnemonic Versus Non-Mnemonic Strategies in Foreign Language Learning Context by Fatemeh Ahmadniay Motlagh & Naser RashidiInternational Journal of Language and Applied LinguisticsBelum ada peringkat

- Children Ls Language ImmersionDokumen32 halamanChildren Ls Language ImmersionCHOFOR VITALISBelum ada peringkat

- Learnirg Est: of ofDokumen9 halamanLearnirg Est: of ofMohd Zahren ZakariaBelum ada peringkat

- Learners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolDokumen13 halamanLearners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolIJELS Research JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Foreign Literature Studies Regarding Attitudes Towards ADokumen2 halamanForeign Literature Studies Regarding Attitudes Towards Adenden2175% (8)

- Studies Involving Successful and Unsuccessful Language LearnersDokumen20 halamanStudies Involving Successful and Unsuccessful Language LearnersAli FarooqBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDFDokumen22 halamanLanguage Learning Strategies of Turkish PDFirfan8791Belum ada peringkat

- 4conchita 1.279150631 PDFDokumen18 halaman4conchita 1.279150631 PDFMichael Alcantara ManuelBelum ada peringkat

- EJ1247964Dokumen11 halamanEJ1247964Ana Mae LinguajeBelum ada peringkat

- Alhaisoni 2012 Language Learning Strategy Use of Saudi EFL Students in An Intensive English Learning ContextDokumen13 halamanAlhaisoni 2012 Language Learning Strategy Use of Saudi EFL Students in An Intensive English Learning ContexthoorieBelum ada peringkat

- JPAIRVol32CC 161 175Dokumen15 halamanJPAIRVol32CC 161 175sophiavalladoresBelum ada peringkat

- Learner Engagement and Language Learning: A Narrative Inquiry of A Successful Language LearnerDokumen16 halamanLearner Engagement and Language Learning: A Narrative Inquiry of A Successful Language LearnerĐức Duy Trần HuỳnhBelum ada peringkat

- Lli 11 PDFDokumen6 halamanLli 11 PDFAldenCabunocBelum ada peringkat

- THE RELATIONSHIP AMONG PROFICIENCY LEVEL, LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY USAGE and LEARNER AUTONOMY OPINIONDokumen13 halamanTHE RELATIONSHIP AMONG PROFICIENCY LEVEL, LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY USAGE and LEARNER AUTONOMY OPINIONSelimBelum ada peringkat

- W5 DocziDokumen21 halamanW5 DocziKỳ Nam HoàngBelum ada peringkat

- Student Language Learning Strategies Across Eight DisciplinesDokumen24 halamanStudent Language Learning Strategies Across Eight DisciplinesAlpin MktBelum ada peringkat

- The Influence of Topics On Listening Strategy UseDokumen12 halamanThe Influence of Topics On Listening Strategy UseRACHEL verrioBelum ada peringkat

- Self AfficacyDokumen13 halamanSelf AfficacyOxtapianusTawarikBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Strategies As Bias Factors in Language Test Performance: A StudyDokumen13 halamanLearning Strategies As Bias Factors in Language Test Performance: A StudyIJ-ELTSBelum ada peringkat

- To Say or Not To Say: ESL Learners' Perspective Towards Pronunciation InstructionDokumen11 halamanTo Say or Not To Say: ESL Learners' Perspective Towards Pronunciation InstructionChloe EisenheartBelum ada peringkat

- Effectiveness of The Vocabulary Learning Strategies On English Vocabulary Learning For Non-English Major College StudentsDokumen6 halamanEffectiveness of The Vocabulary Learning Strategies On English Vocabulary Learning For Non-English Major College StudentsZhyrhyld XyrygzsBelum ada peringkat

- OxfordDokumen16 halamanOxfordKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- Mixed Methods ResearchDokumen14 halamanMixed Methods ResearchKhye Tan100% (1)

- The Ultimate Guide To Running InjuriesDokumen61 halamanThe Ultimate Guide To Running InjuriesKhye Tan100% (4)

- Creative WritingDokumen1 halamanCreative WritingKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- HET 524 Sentence ProcessingDokumen88 halamanHET 524 Sentence ProcessingKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- Language: Marzieh Hadei Koik Shuh Jie Heng Wen Zhuo Goh Sue YinDokumen104 halamanLanguage: Marzieh Hadei Koik Shuh Jie Heng Wen Zhuo Goh Sue YinKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- The Effects of Explicit Instruction of Formulaic SequencesDokumen166 halamanThe Effects of Explicit Instruction of Formulaic SequencesKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- Critical ReviewDokumen2 halamanCritical ReviewFrank Victor MushiBelum ada peringkat

- PresentationDokumen48 halamanPresentationKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- The Effects of Explicit Instruction of Formulaic SequencesDokumen166 halamanThe Effects of Explicit Instruction of Formulaic SequencesKhye TanBelum ada peringkat

- Resumen Unit 1 Unit 2Dokumen6 halamanResumen Unit 1 Unit 2brunoblinkBelum ada peringkat

- Towards Real Communication in English Lessons in Pacific Primary SchoolsDokumen9 halamanTowards Real Communication in English Lessons in Pacific Primary SchoolsnidharshanBelum ada peringkat

- AIDokumen2 halamanAITedo HamBelum ada peringkat

- t12 - Professional Development PlanDokumen3 halamant12 - Professional Development Planapi-455080964Belum ada peringkat

- 5 Guinarte-AriasDokumen7 halaman5 Guinarte-AriasKaren RosasBelum ada peringkat

- Twenty Little Poetry ProjectsDokumen3 halamanTwenty Little Poetry Projectsapi-260214370% (1)

- Monthly Instructional and Supervisory PlanDokumen6 halamanMonthly Instructional and Supervisory PlanTine CristineBelum ada peringkat

- Introdution of Theory X and Theory yDokumen2 halamanIntrodution of Theory X and Theory ymazhar abbas GhoriBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1 KEYDokumen4 halamanAssignment 1 KEYSzilagyi Barna BelaBelum ada peringkat

- Callista Roy's Adaptation Model of NursingDokumen5 halamanCallista Roy's Adaptation Model of Nursinganon_909428755Belum ada peringkat

- Nmba MK01Dokumen19 halamanNmba MK01Ashutosh SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Foreign Policy Analysis Jean Garrison 2003 International StudiesDokumen9 halamanForeign Policy Analysis Jean Garrison 2003 International StudiesSchechter SilviaBelum ada peringkat

- Civil War Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanCivil War Lesson Planapi-335741528Belum ada peringkat

- BUS 5113 - Motivation TheoriesDokumen5 halamanBUS 5113 - Motivation TheoriesEzekiel PatrickBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Lion and The Mouse 2013 PG 13Dokumen7 halamanLesson Plan Lion and The Mouse 2013 PG 13Devandran Deva100% (1)

- How To Correctly Use The Punctuation Marks in English - Handa Ka Funda - Online Coaching For CAT and Banking ExamsDokumen6 halamanHow To Correctly Use The Punctuation Marks in English - Handa Ka Funda - Online Coaching For CAT and Banking ExamsSusmitaDuttaBelum ada peringkat

- Dissertation Topics Criminal PsychologyDokumen5 halamanDissertation Topics Criminal PsychologyBuyingPapersOnlineCollegeSpringfield100% (1)

- English Language Learning Difficulty of Korean Students in A Philippine Multidisciplinary UniversityDokumen10 halamanEnglish Language Learning Difficulty of Korean Students in A Philippine Multidisciplinary UniversityMatt ChenBelum ada peringkat

- English A/B School-Based Assessment (Teacher Approved)Dokumen19 halamanEnglish A/B School-Based Assessment (Teacher Approved)Nick JohnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Henry MurrayDokumen16 halamanHenry MurrayLouriel NopalBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Information MediaDokumen21 halamanVisual Information MediaDiana CabamonganBelum ada peringkat

- EMS Leadership For New EMTsDokumen53 halamanEMS Leadership For New EMTsBethuel Aliwa100% (1)

- 5.05 Character Disintegration AssessmentDokumen3 halaman5.05 Character Disintegration AssessmentChloe FreskBelum ada peringkat

- 21st Cent LPDokumen13 halaman21st Cent LPYelram FaelnarBelum ada peringkat

- Magic ManualDokumen4 halamanMagic ManualNaser ShrikerBelum ada peringkat

- Authentic MaterialsDokumen4 halamanAuthentic MaterialsOllian300Belum ada peringkat

- Kohler, A. 2003, Wittgenstein Meets Neuroscience (Review of Bennett & Hacker 2003)Dokumen2 halamanKohler, A. 2003, Wittgenstein Meets Neuroscience (Review of Bennett & Hacker 2003)khrinizBelum ada peringkat

- IBM SkillsBuild Winter Micro Internship Program 2024Dokumen1 halamanIBM SkillsBuild Winter Micro Internship Program 202422mba002Belum ada peringkat

- Literature Review Concept Map ExamplesDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review Concept Map Examplesc5rr5sqw100% (1)

- State Your Own View of Teaching As A CareerDokumen3 halamanState Your Own View of Teaching As A CareerChristine MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandSurrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)

- 1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundDari Everand1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (13)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageDari EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguagePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (428)

- How Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideDari EverandHow Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideBelum ada peringkat

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDari EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (4)

- Body Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Dari EverandBody Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (81)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonDari EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (21)

- The Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who TeachDari EverandThe Practice of Poetry: Writing Exercises From Poets Who TeachBelum ada peringkat

- Writing to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllDari EverandWriting to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (83)

- Writing Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsDari EverandWriting Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsBelum ada peringkat

- Learn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachDari EverandLearn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (15)

- Idioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsDari EverandIdioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (7)

- How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent ReadingDari EverandHow to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent ReadingPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (26)

- The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguageDari EverandThe Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguagePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (916)

- Spanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesDari EverandSpanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Learn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachDari EverandLearn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (136)

- Learn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachDari EverandLearn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (81)

- Learn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachDari EverandLearn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (151)

- The History of English: The Biography of a LanguageDari EverandThe History of English: The Biography of a LanguagePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (8)

- The Art of Writing: Four Principles for Great Writing that Everyone Needs to KnowDari EverandThe Art of Writing: Four Principles for Great Writing that Everyone Needs to KnowPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (21)

- Dictionary of Fine Distinctions: Nuances, Niceties, and Subtle Shades of MeaningDari EverandDictionary of Fine Distinctions: Nuances, Niceties, and Subtle Shades of MeaningBelum ada peringkat

- Do You Talk Funny?: 7 Comedy Habits to Become a Better (and Funnier) Public SpeakerDari EverandDo You Talk Funny?: 7 Comedy Habits to Become a Better (and Funnier) Public SpeakerPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (20)

- Wit's End: What Wit Is, How It Works, and Why We Need ItDari EverandWit's End: What Wit Is, How It Works, and Why We Need ItPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (24)