Universe in Nutshell Hawking Review

Diunggah oleh

Vladica Barjaktarovic100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

365 tayangan3 halamanreview

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inireview

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

365 tayangan3 halamanUniverse in Nutshell Hawking Review

Diunggah oleh

Vladica Barjaktarovicreview

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 3

Book Review

The Universe in a Nutshell

Reviewed by Steven G. Krantz

The Universe in a Nutshell

Stephen Hawking

Bantam Books, New York, 2001

ISBN 0-553-80202-X

$35.00, 216 pages

Along with Andrew Wiles and Linus Pauling,

Stephen Hawking is one of the very few modern

scientists whose name is a household word.

Hawking, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

(Isaac Newtons chair) at Cambridge University,

has an insight and an imagination that soar across

the cosmos, devising dreams and schemes of how

the universe works. The legend of Hawking is of

course immensely augmented by the fact that he is

afflicted with motor neurone disease (commonly

known in the U.S. as Lou Gehrigs Disease). In fact

he has known that he had the disease since the

age of twenty-one (Hawking is now sixty). He did

not expect to live to the age of twenty-five and was

tempted to despair. Instead, by his own telling,

the knowledge of having this deadly illness gave

him courage and hope and a will to live. It took his

aimless and futile life (which Hawking himself has

described elsewhere in painful and shamefaced

detail) and gave it direction and purpose. And he has

applied that newfound Gestalt to the development

of ideas in theoretical physics.

To read any of Hawkings many books,

one would never realize just how devastating

Steven G. Krantz is chair and professor in the Department

of Mathematics at Washington University in St. Louis. His

e-mail address is sk@math.wustl.edu.

570

NOTICES

OF THE

AMS

Hawkings illness is.

He speaks of it only

rarely and as if it

were just a minor inconvenience. However, his friend Roger

Penrose has told me

quite frankly that it

requires an army of

people just to keep

Hawking going: He

cannot speak, he cannot walk, he cannot

pick up a pen, and he

cannot even breathe

on his own. Hawkings popular writing

is redolent of joy and good humor and great high

spirits. One cannot but think that the world would

be a better place if we all had the good and optimistic frame of mind of Stephen Hawking. His is

truly a profile in courage.

Stephen Hawkings A Brief History of Time [HAW]

has been a publishing phenomenon. Penned in

1988, it spent more than four years on the bestseller

lists and sold more than ten million copies in forty

languages. As Hawkings postdoc Nathan Myhrvold

(of Microsoft fame) has said, Hawking has sold

more books on physics than Madonna has on sex.

Part of the appeal of Time is the Hawking mystique, but a considerable part of its charm is

the breezy and friendly style in which the book

is written. Like mathematics, physics is stark and

rigorous and forbidding, enshrouded by technical

VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5

lingo and recondite ideas. Although relativity,

the uncertainly principle, the speed of light,

and black holes hold great charm and fascination

for the layman, most writings on these topics are

either facile and incorrect or onerous and obscure.

Hawking forges a brilliant path between these two

extremes. Obviously everything he says is authoritative and accurate; in those instances where he

must blow smoke, he is quite honest about it and

still gives the reader a sense of what is going on.

Hawking uses analogy and humor and example

and metaphor to depict his ideas in an attractive

and compelling manner.

So if A Brief History of Time is the be-all and endall of the popular conception of cosmology, then

why is there any need for another book? Well, publishers like to sell books; and Stephen Hawking is

a best-selling author. But let us be more charitable.

By Hawkings own telling, Time is a tough go for

the untrained reader. As I was reading the books

description of the forward and backward light

cones, I was struck by how simple and obvious

these ideas are to a trained scientist (like myself),

and how utterly obscure they must be to a tyro. The

rather more expensive illustrated edition of Time

has many attractive graphics, but the original and

widely disseminated first edition has only a few simple line drawings. As a result, and in spite of its

immense popularity, the book comes off as a bit

dry and uninviting. The common wisdom is that

millions bought the book, but few have gotten past

the first twenty pages.

Enter The Universe in a Nutshell. In his preface,

Hawking acknowledges the difficulties noted in

the preceding paragraph and touts the importance

of good pictures. This new book, he claims, will be

much more accessible to the lay reader. He points

out, wisely I think, that Time is written in a linear

orderjust like a mathematical monograph.

Chapter n + 1 in Time depends strictly on Chapters

1 to n . Of course the mathematical scientist is

accustomed to this type of vertical development.

The average reader is not. In a much-read article

[THU] on mathematics education, William Thurston

points out that mathematics is a tall subject. The

student painstakingly climbs up the pole to the

point where he loses his grip, and then he falls

down (never to rise again). Thurston argues for the

value of making mathematics a wider subject

with a broad-based infrastructure. Hawking has

got this message. In his new book, his organization

pattern is a tree: After the introductory material,

the book branches out in several different directions.

The reader may dip into the succeeding chapters

at will and jump around as interest and inclination

dictate. Perhaps more important is that Nutshell

has marvelous figures, many of them in full color.

These are pictures (very elementary ones) of scientific ideas, or of equations, or of the scientists

MAY 2002

themselves. There are sidebars on Kurt Gdel and

Kip Thorne and Richard Feynman and John Wheeler

and Star Trek and any number of other familiar

people and topics. The book is just plain fun. Even

when the casual reader gets lost, and he certainly

will, he will be encouraged and carried along by the

graphics and by the verbal byplay that accompanies

the more serious text proper. An added feature is

that the book has a concise and useful glossary.

Many a reader will have difficulty keeping track of

terms and ideas, and this tool will certainly keep

many an aficionado going.

There are perhaps those who will criticize Nutshell for not being sufficiently serious. Popular

singer/songwriter Neil Sedaka says that people

fault him for having too much fun with his music.

Certainly Hawking has tremendous fun with his

physics. A few sample passages suggest the overall tone:

Newton occupied the Lucasian chair at

Cambridge that I now hold, though it

wasnt electrically operated in his time.

This [time dilation as explained by relativity theory] might suggest that if one

wanted to live longer, one should keep

flying to the east so that the planes

speed is added to the earths rotation.

However, the tiny fraction of a second

one would gain would be more than

canceled by eating airline meals.

I estimate the probability that Kip

Thorne could go back and kill his grandfather [using time travel] as less than

one in ten with a trillion trillion trillion

trillion trillion zeroes after it. Thats a

pretty small probability, but if you look

closely at the picture of Kip, you may

see a slight fuzziness around the edges.

That corresponds to the faint possibility that some bastard from the future

came back and killed his grandfather,

so hes not really there.

The reader of this review can surely see that I am

a great admirer of Stephen Hawking. His strength

and his courage and his exuberance are both infectious and inspiring. But I also appreciate the

tremendous intellectual effort that it takes to explain a subject as technical and deep as cosmology

to the lay public. It takes real gifts, and tremendous

determination, to pull this off. It requires a certain

amount of chutzpah even to try it. The likelihood

of failure is considerable, and the likelihood of

embarrassment before ones colleagues is huge.

Yet we in the mathematical sciences have suffered

in the public eye, have suffered in the derby for

NOTICES

OF THE

AMS

571

funding, and have suffered among the sciences

because we have not been willing to take these

risks. I can only hope that we will all see Stephen

Hawking as a role model and that we will therefore

tryeven in a small way, perhaps by consenting

to an interview with the campus newspaperto

communicate as Hawking has. There is much to be

gained, and the risks are well worth it. Now that

Hawking has forged the path, it is much easier for

the rest of us to follow.

Hawking confesses that when he wrote A Brief

History of Time he felt that physicists were on the

verge of a great overarching theory that would, in

particular, reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics. Part of the purpose of the present

book is to bring the reader up to date with progress

on this unified theory in the past thirteen years.

Hawking addresses this goal by way of describing

various avenues of research that he, himself, has

pursued. This of course makes perfect sense, and

he does a splendid job of giving the reader a feel

for p-branes, string theory, Feynmans multiple

histories, black holes, and many other cutting edge

ideas. I am not at all sure that, having labored

through the book, the reader will have a clear idea

of where we are now as compared to where we were

in 1988. One is tempted at this point to compare

Hawkings new book with Brian Greenes The Elegant Universe [GRE]. Greene states point blank in

his preface that physicists believe that they

have finally found a framework for stitching these

insights together into a seamless wholea single

theory that, in principle, is capable of describing

all physical phenomena. He then proceeds to

spend 387 pages telling us (by way of superstring

theory and the like) how the physicists have

achieved this end. Greene is less interested in entertaining us than in telling a very serious story.

As a result, his book is rather more cerebral and

ponderous than Hawkings. It has nevertheless

been well received and has certainly acquainted a

broad cross-section of the populace with some

important scientific developments. But the book is

perhaps more austere than even A Brief History of

Time. It contains much more solid information

than, and will reach a much more limited audience than, The Universe in a Nutshell. This is a

trade-off with which both authors should be

comfortable.

The Universe in a Nutshell has many features

going for it. Like A Brief History of Time, it has a

delightfully wry and enticing title. It draws the

reader in quickly and painlessly and sustains him

with wit and popular touchstones and fun. The

reader of Nutshell will know, because Hawking has

told him quite explicitly, that we have not yet

reached our goal of a unified theory and that we

probably never will. To Hawkings mind, and to

mine as well, this is all to the good because the

572

NOTICES

OF THE

AMS

journey is much more enthralling than the finish.

The reader of Nutshell will have been left with

many opened doors and unanswered questions, and

this is clearly how Hawking wants it. Readers of his

next book will have all the necessary prerequisites.

References

[GRE] B. GREENE, The Elegant Universe, Norton, New York,

1999.

[HAW] S. HAWKING, A Brief History of Time, updated

edition, Bantam Books, New York, 1996.

[THU] W. P. THURSTON, Mathematical Education, Notices 37

(1990), 844850.

VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Structure of Scientific RevolutionsDari EverandThe Structure of Scientific RevolutionsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4)

- Fisher Paykel SmartLoad Dryer DEGX1, DGGX1 Service ManualDokumen70 halamanFisher Paykel SmartLoad Dryer DEGX1, DGGX1 Service Manualjandre61100% (2)

- A Brief History of TimeDokumen10 halamanA Brief History of TimePool Orellana Laura0% (1)

- Gevin Giorbran - Everything Forever - Learning To See TimelessnessDokumen348 halamanGevin Giorbran - Everything Forever - Learning To See Timelessnesschaserdavid100% (3)

- The Dancing Universe: From Creation Myths to the Big BangDari EverandThe Dancing Universe: From Creation Myths to the Big BangPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (16)

- The Goldilocks Enigma: Why Is the Universe Just Right for Life?Dari EverandThe Goldilocks Enigma: Why Is the Universe Just Right for Life?Belum ada peringkat

- The Short History of Nearly Everything-Bill BrysonDokumen29 halamanThe Short History of Nearly Everything-Bill BrysonSneha Sadvilkar31% (16)

- The Short History of Nearly Everything-Bill BrysonDokumen29 halamanThe Short History of Nearly Everything-Bill BrysonSneha Sadvilkar31% (16)

- Tanya TalagaDokumen3 halamanTanya Talagasarbjit singh BadhanBelum ada peringkat

- The Revolution Will Not Be Psychologized-TranscriptDokumen28 halamanThe Revolution Will Not Be Psychologized-TranscriptNicolas Avila R100% (1)

- The universe is intelligent. The soul exists. Quantum mysteries, multiverse, entanglement, synchronicity. Beyond materiality, for a spiritual vision of the cosmos.Dari EverandThe universe is intelligent. The soul exists. Quantum mysteries, multiverse, entanglement, synchronicity. Beyond materiality, for a spiritual vision of the cosmos.Penilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- On The Shoulders of Giants Final 052909Dokumen3 halamanOn The Shoulders of Giants Final 052909content magazine100% (1)

- Halton Arp - Seeing Red - Red Shift, Cosmology, and Academic Science PDFDokumen319 halamanHalton Arp - Seeing Red - Red Shift, Cosmology, and Academic Science PDFPeterAspegren100% (8)

- Greek MythsDokumen80 halamanGreek Mythsautoerotic100% (21)

- Abr Sinai Onshore Gas Pipeline PDFDokumen42 halamanAbr Sinai Onshore Gas Pipeline PDFhamza2085100% (1)

- On Grammar and GrammaticsDokumen34 halamanOn Grammar and GrammaticsArthur Melo SaBelum ada peringkat

- Navigating Loneliness: How to Connect with Yourself and OthersDari EverandNavigating Loneliness: How to Connect with Yourself and OthersBelum ada peringkat

- Death doesn't exist: The Mother on Death, Sri Aurobindo on RebirthDari EverandDeath doesn't exist: The Mother on Death, Sri Aurobindo on RebirthBelum ada peringkat

- What Really Happens When You Die?: Cosmology, time and youDari EverandWhat Really Happens When You Die?: Cosmology, time and youBelum ada peringkat

- The Nature of Things: Navigating Everyday Life with GraceDari EverandThe Nature of Things: Navigating Everyday Life with GraceBelum ada peringkat

- The Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisDari EverandThe Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisBelum ada peringkat

- A Brief History of TimeDokumen10 halamanA Brief History of TimeJerome JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- God Created The Integers Stephen Hawking EbookDokumen3 halamanGod Created The Integers Stephen Hawking EbookGladysBelum ada peringkat

- Book ReviewDokumen6 halamanBook ReviewShehreen YasserBelum ada peringkat

- New Light Through Old Windows: Exploring Contemporary Science Through 12 Classic Science Fiction TalesDari EverandNew Light Through Old Windows: Exploring Contemporary Science Through 12 Classic Science Fiction TalesBelum ada peringkat

- The Universe is Intelligent. The Soul Exists. Quantum Mysteries, Multiverse, Entanglement, Synchronicity. Beyond Materiality, for a Spiritual Vision of the Cosmos.: Quantum mysteries, multiverse, entanglement, synchronicity. Beyond materiality, for a spiritual vision of the cosmos.Dari EverandThe Universe is Intelligent. The Soul Exists. Quantum Mysteries, Multiverse, Entanglement, Synchronicity. Beyond Materiality, for a Spiritual Vision of the Cosmos.: Quantum mysteries, multiverse, entanglement, synchronicity. Beyond materiality, for a spiritual vision of the cosmos.Belum ada peringkat

- UniverseinaNutshell HawkingReviewbyImpeyDokumen3 halamanUniverseinaNutshell HawkingReviewbyImpeyEsra Kavaklı DumanBelum ada peringkat

- BabyUniverses PDFDokumen5 halamanBabyUniverses PDFmanishbabuBelum ada peringkat

- (MasterMinds) Searle, John Rogers - Mind, Language and Society - Philosophy in The Real World-Basic Books (1999)Dokumen213 halaman(MasterMinds) Searle, John Rogers - Mind, Language and Society - Philosophy in The Real World-Basic Books (1999)Yentl MAGNOBelum ada peringkat

- Lethbridge Part 1Dokumen21 halamanLethbridge Part 1Juan Miguel ll100% (1)

- The Uses of Obscurity by Alan Sokal and Jean BricmontDokumen8 halamanThe Uses of Obscurity by Alan Sokal and Jean BricmontcountofmontecristoBelum ada peringkat

- Rowlands 2014Dokumen3 halamanRowlands 2014Perpetual AmazinggirlBelum ada peringkat

- The Nagel Flap: Mind and Cosmos: "Most Despised Science Book of 2012."Dokumen12 halamanThe Nagel Flap: Mind and Cosmos: "Most Despised Science Book of 2012."alfredo_ferrari_5Belum ada peringkat

- Presentation 1Dokumen17 halamanPresentation 1Azra Husejnovic100% (1)

- Julian Barbour The Janus Point A New Theory of TimeDokumen371 halamanJulian Barbour The Janus Point A New Theory of TimeZaza Doborjginidze100% (3)

- Celestial Science - Max Steinberg - PDF For ComputersDokumen170 halamanCelestial Science - Max Steinberg - PDF For ComputersMax Steinberg100% (4)

- God Created The IntegersDokumen3 halamanGod Created The IntegersAnnie50% (2)

- L'univers est intelligent. L'âme existe. Mystères quantiques, multivers, intrication, synchronicité. Au-delà de la matérialité, pour une vision spirituelle du cosmos.Dari EverandL'univers est intelligent. L'âme existe. Mystères quantiques, multivers, intrication, synchronicité. Au-delà de la matérialité, pour une vision spirituelle du cosmos.Belum ada peringkat

- Quantum Physics is NOT Weird: It is how our consciousness creates our reality. Second Edition, Revised and Enlarged.Dari EverandQuantum Physics is NOT Weird: It is how our consciousness creates our reality. Second Edition, Revised and Enlarged.Belum ada peringkat

- Ted Hall's Playing.... DeckDokumen149 halamanTed Hall's Playing.... DeckReed BurkhartBelum ada peringkat

- Autobiography of StephenDokumen6 halamanAutobiography of StephenHimani VarshneyBelum ada peringkat

- Stephen Hawking NotesDokumen4 halamanStephen Hawking NotesVanshikaBelum ada peringkat

- Math and Science - Related Books You Can Read Recommended by Mr. BrandenburgDokumen30 halamanMath and Science - Related Books You Can Read Recommended by Mr. BrandenburgRaviBelum ada peringkat

- The Perfection of Freedom: Schiller, Schelling, and Hegel between the Ancients and the ModernsDari EverandThe Perfection of Freedom: Schiller, Schelling, and Hegel between the Ancients and the ModernsBelum ada peringkat

- No66 Atlantis Rising Magazine Lost Civiization The Bermuda TriangleDokumen84 halamanNo66 Atlantis Rising Magazine Lost Civiization The Bermuda Triangleww-we100% (2)

- This Fascinating Astronomy Science For EveryoneDokumen304 halamanThis Fascinating Astronomy Science For Everyonestreetba100% (2)

- A Brief History of TimeDokumen5 halamanA Brief History of TimeRaghav Rastogi14% (7)

- 16: Implications of The Model: The Fool's SecretDokumen12 halaman16: Implications of The Model: The Fool's Secretdocwavy9481Belum ada peringkat

- A Brief History of TimeDokumen1 halamanA Brief History of TimeCarlos Andres AndradeBelum ada peringkat

- FR Choronzon - Liber Cyber PDFDokumen133 halamanFR Choronzon - Liber Cyber PDFaleisterBelum ada peringkat

- Godel Escher Bach Ebook ItaDokumen4 halamanGodel Escher Bach Ebook ItaJulie0% (1)

- SharadeDokumen2 halamanSharadeVarun JayaramanBelum ada peringkat

- Achilles In the Quantum Universe: The Definitive History Of InfinityDari EverandAchilles In the Quantum Universe: The Definitive History Of InfinityBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper Science FictionDokumen5 halamanResearch Paper Science Fictionafeekqmlf100% (1)

- Grammar, Syntax, Semantics, DiscourseDokumen4 halamanGrammar, Syntax, Semantics, DiscourseVladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- Academic Ranking of Worl..Dokumen12 halamanAcademic Ranking of Worl..Vladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- General AbilityDokumen3 halamanGeneral AbilityIsma-MABelum ada peringkat

- Adverbs of Frequency 1Dokumen2 halamanAdverbs of Frequency 1Vladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- Guide4BankExams English GrammarDokumen11 halamanGuide4BankExams English GrammarShiv Ram Krishna100% (3)

- Urn NBN Si Doc Mws4axomDokumen12 halamanUrn NBN Si Doc Mws4axomVladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- German IIDokumen20 halamanGerman IIFranco SalomoneBelum ada peringkat

- SC English ReqsDokumen1 halamanSC English ReqsVladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- JokeDokumen1 halamanJokeVladica BarjaktarovicBelum ada peringkat

- Iot Lab RecordDokumen33 halamanIot Lab RecordMadhavan Jayarama MohanBelum ada peringkat

- RespiratorypptDokumen69 halamanRespiratorypptMichelle RotairoBelum ada peringkat

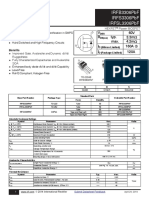

- Irfb3306Pbf Irfs3306Pbf Irfsl3306Pbf: V 60V R Typ. 3.3M: Max. 4.2M I 160A C I 120ADokumen12 halamanIrfb3306Pbf Irfs3306Pbf Irfsl3306Pbf: V 60V R Typ. 3.3M: Max. 4.2M I 160A C I 120ADirson Volmir WilligBelum ada peringkat

- Initial and Final Setting Time of CementDokumen20 halamanInitial and Final Setting Time of CementTesfayeBelum ada peringkat

- Lab Assignment - 2: CodeDokumen8 halamanLab Assignment - 2: CodeKhushal IsraniBelum ada peringkat

- Bates Stamped Edited 0607 w22 QP 61Dokumen6 halamanBates Stamped Edited 0607 w22 QP 61Krishnendu SahaBelum ada peringkat

- PPF CalculatorDokumen2 halamanPPF CalculatorshashanamouliBelum ada peringkat

- Project 10-Fittings DesignDokumen10 halamanProject 10-Fittings DesignVishwasen KhotBelum ada peringkat

- Cleats CatalogueDokumen73 halamanCleats Cataloguefire123123Belum ada peringkat

- Testing, Adjusting, and Balancing - TabDokumen19 halamanTesting, Adjusting, and Balancing - TabAmal Ka100% (1)

- EXP.2 Enzyme Extraction From BacteriaDokumen3 halamanEXP.2 Enzyme Extraction From BacteriaLinhNguyeBelum ada peringkat

- Rotational Dynamics-07-Problems LevelDokumen2 halamanRotational Dynamics-07-Problems LevelRaju SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Fiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992Dokumen58 halamanFiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992shafeeqm3086Belum ada peringkat

- Grade-9 (3rd)Dokumen57 halamanGrade-9 (3rd)Jen Ina Lora-Velasco GacutanBelum ada peringkat

- CSS Lab ManualDokumen32 halamanCSS Lab ManualQaif AmzBelum ada peringkat

- Math 10 Q2 Week 5Dokumen3 halamanMath 10 Q2 Week 5Ken FerrolinoBelum ada peringkat

- User's Manual HEIDENHAIN Conversational Format ITNC 530Dokumen747 halamanUser's Manual HEIDENHAIN Conversational Format ITNC 530Mohamed Essam Mohamed100% (2)

- SL-19536 - REV2!02!13 User Manual MC CondensersDokumen68 halamanSL-19536 - REV2!02!13 User Manual MC CondensersCristian SevillaBelum ada peringkat

- Allison 1,000 & 2,000 Group 21Dokumen4 halamanAllison 1,000 & 2,000 Group 21Robert WhooleyBelum ada peringkat

- Polya Problem Solving StrategiesDokumen12 halamanPolya Problem Solving StrategiesGwandaleana VwearsosaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To PercolationDokumen25 halamanIntroduction To Percolationpasomaga100% (1)

- SkyCiv Beam - Hand Calculations - AJW8CTBuLE8YKrkKaG8KTtPAw8k74LSYDokumen13 halamanSkyCiv Beam - Hand Calculations - AJW8CTBuLE8YKrkKaG8KTtPAw8k74LSYsaad rajawiBelum ada peringkat

- Data and Specifications: HMR Regulated MotorsDokumen21 halamanData and Specifications: HMR Regulated MotorsBeniamin KowollBelum ada peringkat

- US2726694 - Single Screw Actuated Pivoted Clamp (Saxton Clamp - Kant-Twist)Dokumen2 halamanUS2726694 - Single Screw Actuated Pivoted Clamp (Saxton Clamp - Kant-Twist)devheadbot100% (1)

- CFMDokumen16 halamanCFMShoaibIqbalBelum ada peringkat

- Orthographic Views in Multiview Drawings: Autocad 2015 Tutorial: 2D Fundamentals 5-1Dokumen30 halamanOrthographic Views in Multiview Drawings: Autocad 2015 Tutorial: 2D Fundamentals 5-1Uma MageshwariBelum ada peringkat

- 3PAR DISK MatrixDokumen6 halaman3PAR DISK MatrixShaun PhelpsBelum ada peringkat

- Air Movements 06-26-2019 - Full ScoreDokumen5 halamanAir Movements 06-26-2019 - Full ScoreMichael CrawfordBelum ada peringkat