Review: Functional Dyspepsia: Past, Present, and Future

Diunggah oleh

kookiescreamDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Review: Functional Dyspepsia: Past, Present, and Future

Diunggah oleh

kookiescreamHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

J Gastroenterol 2008; 43:251255

DOI 10.1007/s00535-008-2167-8

Review

Functional dyspepsia: past, present, and future

BRECHT GEERAERTS and JAN TACK

Center for Gastroenterological Research K.U. Leuven, 49 Herestraat, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a highly prevalent gastrointestinal disorder characterized by symptoms originating from the gastroduodenal region in the absence of

underlying organic disease that readily explains the

symptoms. The Rome II consensus, which defined FD

as the presence of unexplained pain or discomfort in the

epigastrium, had a number of drawbacks, including an

unjustified focus on pain, inclusion of a large number

of nonspecific symptoms, and an unclear position on

overlap with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The Rome III consensus redefined FD as the presence of epigastric pain

or burning, postprandial fullness or early satiation in the

absence of underlying organic disease. Frequent overlap

with GERD and IBS is acknowledged but does not

exclude a diagnosis of FD. A subgroup classification

into postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain

syndrome was proposed. Ongoing studies will clarify

the impact of this subdivision on clinical management

and treatment outcomes.

Key words: Rome III consensus, postprandial distress

syndrome (PDS), epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), postprandial fullness, early satiation

Introduction

In up to half of patients seen by gastroenterologists,

a standard work-up, which may include endoscopy,

laboratory testing, and radiological evaluation, fails to

provide an explanation for the patients symptoms.

This group of patients is referred to as patients with

functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), as it is

Received / Accepted: January 21, 2008

Reprint requests to: J. Tack

assumed that abnormalities of gastrointestinal function

underlie the generation of their symptoms. According

to the Rome consensus process, FGIDs in adults are

subdivided into six major domains, according to the

area of the gastrointestinal tract where symptoms are

thought to originate.1

Functional dyspepsia (FD), a functional syndrome

thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, is

one of the most prevalent FGIDs. Over the last 20

years, the definition of FD has undergone major changes

from the 1988 working party definition of dyspepsia, to

the consecutive Rome I, Rome II, and most recently

Rome III definitions,26 in line with changing understanding of the categorization and the pathophysiological basis of this disorder.

Rome I and II definitions

According to the Rome I and Rome II definitions, FD

was defined as the presence of pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, in the absence of organic

disease that readily explained the symptoms.4,5 While

the meaning of pain is readily understood, the notion of

discomfort is more difficult to grasp. It has remained

unsettled whether discomfort is a mild variant of pain

or a separate symptom complex.7 Moreover, discomfort

comprises a number of different nonpainful symptoms,

including upper abdominal fullness, early satiety, bloating, nausea, epigastric burning, belching, and vomiting.

While Rome I included some reflux symptoms with FD,

and recognized a subgroup of reflux-like dyspepsia (see

below), the Rome II definition of FD excluded patients

with predominant heartburn.4,5 The Rome II definition

also excluded irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as a cause

of the symptoms by adding the requirement of no evidence that dyspepsia is exclusively relieved by defecation or associated with the onset of a change in stool

frequency or stool form.

252

B. Geeraerts and J. Tack: Functional dyspepsia

Subgroups of functional dyspepsia according to

Rome I and II

Several working teams, including the Rome I and Rome

II consensus groups, considered FD a heterogeneous

condition that could be subdivided into symptom

subgroups, although the names and definitions have

varied.26 On the basis of symptom clusters, the Rome

I consensus identified subgroups of ulcer-like and dysmotility-like dyspepsia.4 The Rome II consensus identified the same subgroups based on the predominant

symptom being pain or discomfort.5

Previous working parties had also recognized a reflux-like subgroup of FD,2,3 but the Rome I consensus

proposed that these patients be considered to have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) until proven otherwise, and this was maintained in the Rome II

consensus.4,5

present in all patients with FD, and there is considerable

variation in the symptom pattern among patients. The

Rome III committee therefore proposed to decrease

the number of FD symptoms to four specific symptoms

(postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain,

and epigastric burning) thought to originate from the

gastroduodenal region (Table 1). While other symptoms may coexist, they are not considered cardinal FD

symptoms as they may arise from other areas of the

gastrointestinal tract or the body. Bloating, for instance,

may be derived from the bowel, as it often occurs in IBS

or in functional bloating, so this was not considered

a cardinal symptom of dyspepsia. Similarly, nausea is

often of central origin, and together with vomiting is

also not considered a localizing symptom. Belching and

heartburn are considered esophageal rather than gastroduodenal symptoms.

Rationale for new subclasses of functional dyspepsia

Rationale for a new definition of functional dyspepsia

In the Rome II definition of FD, epigastric pain was

considered a key feature of FD, and seven other symptoms were grouped under the term discomfort.

Besides the lack of a clearly defined distinction between

pain and intense discomfort, analyses of the symptom

pattern do not support singling out pain over all other

symptoms.8 In fact, there is no single symptom that is

The Rome II definitions proposed a subclassification of

FD based on the predominant symptom.5 However,

subsequent research has shown that identification of the

predominant symptom lacks stability over a short time

period.8,9 Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence of

heterogeneity of FD based on factor analyses in the

general population and in referral populations (Table

2). These analyses have failed to support the existence

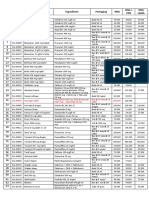

Table 1. Dyspeptic symptoms according to the Rome III consensus

Epigastric pain

Postprandial fullness

Early satiation

Epigastric burning

Epigastric refers to the region between the umbilicus and lower end of the sternum, marked by

the midclavicular lines. Pain refers to a subjective, unpleasant sensation; some patients may feel

that tissue damage is occurring. Epigastric pain may or may not have a burning quality. Other

symptoms may be extremely bothersome without being interpreted by the patient as pain.

An unpleasant sensation like the prolonged persistence of food in the stomach.

A feeling that the stomach is overfilled soon after starting to eat, out of proportion to the size of

the meal being eaten, so that the meal cannot be finished. Previously, the term early satiety

was used, but satiation is the correct term for the disappearance of the sensation of appetite

during food ingestion.

Epigastric refers to the region between the umbilicus and the lower end of the sternum, marked

by the midclavicular lines. Burning refers to an unpleasant subjective sensation of heat.

Table 2. Evidence of heterogeneity of functional dyspepsia based on factor analyses in the general population and in

referral populations

Study

Westbrook 2002 (11)

Fischler 2003 (12)

Tack 2003 (13)

Jones 2003 (14)

Kwan 2003 (15)

Whitehead 2003 (16)

Camilleri 2005 (17)

Piessevaux 2008 (18)

Population

Factors

Population sample

Tertiary care

Tertiary care

Population sample

Tertiary care

Tertiary care

Population sample

Population sample

2300

438

638

888

1012

1041

21128

2025

3 dyspeptic symptom factors

4 dyspeptic symptom factors

3 dyspeptic symptom factors

3 dyspeptic symptom factors

3 dyspeptic symptom factors

4 dyspeptic symptom factors

3 dyspeptic symptom factors

3 or 4 dyspeptic symptom factors

B. Geeraerts and J. Tack: Functional dyspepsia

253

Functional Dyspepsia

Postprandial distress

syndrome (PDS):

Meal-related FD

- Early satiation

- Postprandial fullness

Epigastric pain

syndrome (EPS):

Meal-unrelated FD

- Epigastric pain

- Epigastric burning

of FD as a homogeneous condition.1118 Although there

are some differences between studies, symptom groupings are consistently found, and these include an epigastric pain factor, a factor of meal-induced symptoms,

including postprandial fullness or early satiation, and

a nausea factor (with or without vomiting). In some

studies, belching also appears as a separate fourth

symptom group.

By definition, certain symptoms such as early satiation or postprandial fullness are related to the ingestion

of a meal. All factor analysis studies identified a separate factor of meal-related symptoms. Systematic studies

revealed that symptoms are induced or worsened by

meal ingestion in the majority of patients with dyspeptic

symptoms, but there are patients in whom symptoms

are not related to ingestion of a meal.18,19 The Rome III

committee proposed a distinction between meal-induced

symptoms and meal-unrelated symptoms to be pathophysiologically and clinically relevant, and this distinction forms the basis of newly defined subcategories of

FD. FD is now further subdivided into two new diagnostic categories: (1) meal-induced dyspeptic symptoms

[postprandial distress syndrome (PDS)], characterized

by postprandial fullness and early satiation, and (2) epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), characterized by epigastric pain and burning (Fig. 1). It is likely that refinements

(e.g., distinctions between meal-related pain and interdigestive pain) may be necessary in the future, but such

refinements await further studies.

Overlap with gastroesophageal reflux disease and with

irritable bowel syndrome

The issue of overlap with GERD has been a difficult

topic. While earlier working parties considered a group

of reflux-like dyspepsia,2,3 the Rome committees consid-

Fig. 1. Rome III subgroups of functional

dyspepsia (FD)

ered this primarily a GERD group, and it was excluded

from FD.4,5 The Rome II definition excluded patients

with predominant heartburn from the FD spectrum,5

but additional studies have demonstrated that the predominant symptom approach does not reliably identify

all patients with GERD.2022

Furthermore, it is clear that there is not a uniform

interpretation of the implications of the guideline that

excludes predominant heartburn. On the one hand,

several large studies included heartburn and even acid

regurgitation as typical symptoms of dyspepsia.23,24

On the other hand, regulatory authorities often required

exclusion of all heartburn in FD therapeutic trials.

Whereas the Rome II definition of FD excluded patients

with predominant heartburn and was unclear on nonpredominant heartburn, the Rome III definition states

that heartburn is not a gastroduodenal symptom,

although it often occurs simultaneously with FD symptoms, and its presence does not exclude the diagnosis

of FD.6 Similarly, the frequently occurring overlap of

FD with IBS25 is explicitly recognized.6

Implications for patient management

The Rome III subdivision of FD was proposed under

the assumption that different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms would be present in each of the

subgroups and, consequently, that different treatment

modalities would be most suitable for each subgroup.

Acid suppression is a frequently used first-line

therapy, especially in the absence of Helicobacter pylori

infection. In the presence of H. pylori, eradication is

often proposed, but meta-analyses show that the yield

in terms of symptom relief is limited.26 A meta-analysis

of controlled, randomized trials with proton pump

inhibitors (PPIs) in FD reported that this class of agents

254

B. Geeraerts and J. Tack: Functional dyspepsia

Dyspeptic symptoms

Endoscopy

70%

Functional dyspepsia

Organic dyspepsia

(eradicate if HP+)

Meal-related (PDS)

Meal-unrelated (EPS)

Prokinetic

Acid suppressive

Add or switch to

acid suppressive

Add or switch

to prokinetic

Tricyclic agent if refractory

was superior to placebo.27 However, much of this benefit

may be explained by unrecognized GERD. According

to this meta-analysis, epigastric pain, but not mealrelated symptoms, seems to respond to a PPI.27 Similarly, meta-analyses suggest that prokinetics may be

superior to placebo for so-called motility-like dyspepsia, but publication bias may also account at least in part

for some of the positive meta-analyses in the literature.28,29 Antidepressants are often used in refractory

cases, but the evidence for their efficacy is limited.30

Nevertheless, on the basis of the available pre-Rome

III literature, one might propose initial therapy with

a PPI in EPS, and with a prokinetic in PDS. In case

of refractoriness, combined therapy or a psychotropic

agent might be considered (Fig. 2). A priori H. pylori

eradication can be considered in all infected FD patients,

but the yield will be limited, and this is a subgroup that

is expected to become progressively smaller with time.

Investigating and proving the usefulness of such a management algorithm will be on the agenda for the near

future.

References

1. Drossman DA. The Rome Foundation and Rome III. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007;19:7836.

2. Colin-Jones DG, Bloom B, Bodemar G, Crean G, Freston J,

Gugler R, et al. Management of dyspepsia: report of a working

party. Lancet 1988;1:5769.

3. Barbara L, Camilleri M, Corinaldesi R, Crean GP, Heading RC,

Johnson AG, et al. Definition and investigation of dyspepsia.

Consensus of an international ad hoc working party. Dig Dis Sci

1989;34:12726.

Fig. 2. Possible treatment algorithm

for functional dyspepsia according to the

Rome III classification. Ongoing research

will evaluate the usefulness of this algorithm. HP+, Helicobacter pylori-positive;

PDS, postprandial distress syndrome;

EPS, epigastric pain syndrome

4. Talley NJ, Koch KL, Koch M, et al. Functional dyspepsia: a classification with guidelines for diagnosis and management. Gastrointest Int 1991;4:14560.

5. Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, Koch KL, Malagelada JR,

Tytgat GNJ. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut 1999;45

(Suppl) II:3742.

6. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu PJ, Malagelada

JR, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology

2006;130:146679.

7. Stanghellini V. Review article: pain versus discomfortis differentiation clinically useful? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:

1459.

8. Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment

of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2004;127:123955.

9. Laheij RJ, De Koning RW, Horrevorts AM, Rongen RJ, Rossum

LG, Witteman EM, et al. Predominant symptom behavior in

patients with persistent dyspepsia during treatment. J Clin

Gastroenterol 2004;38:4905.

10. Talley NJ, Locke GR 3rd, Lahr BD, Zinsmeister AR, Tougas G,

Ligozio G, et al. Functional dyspepsia, delayed gastric emptying,

and impaired quality of life. Gut 2006;55:9339.

11. Westbrook JI, Talley NJ. Empiric clustering of dyspepsia into

symptom subgroups: a population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:91723.

12. Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Persoons P, De Gucht V, Broekaert

D, Luyckx K, et al. Evidence-based subtypes in functional dyspepsia with confirmatory factor analysis: psychosocial and physiopathological correlates. Gastroenterology 2003;124:90310.

13. Tack J, Talley NJ, Coulie B, Dubois D, Jones M. Association of

weight loss with gastrointestinal symptoms in a tertiary-referred

patient population. Gastroenterology 2003 (abstract).

14. Jones M, Talley N, Coulie B, Dubois J, Tack J. Association of

weight loss with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gastroenterology

2003 (abstract).

15. Kwan AC, Bao TN, Chakkaphak S, Chang FY, Ke MY, Law NM,

et al. Validation of Rome II criteria for functional gastrointestinal

disorders by factor analysis of symptoms in Asian patient sample.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:796802.

16. Whitehead WE, Bassotti G, Palsson O, Taub E, Cook EC III,

Drossman DA. Factor analysis of bowel symptoms in US and

Italian populations. Dig Liv Dis 2003;35:77483.

B. Geeraerts and J. Tack: Functional dyspepsia

17. Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Stewart WF, Sonnenberg A, et al. Results from the US upper gastrointestinal study:

prevalence, socio-economic impact and functional gastrointestinal disorder subgroups identified by factor and cluster analysis.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:54352.

18. Piessevaux H, De Winter B, Louis E, Muls V, De Looze D,

Pelckmans P, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms in the general population: a factor and cluster analysis of symptom groupings. 2008

(submitted).

19. Castillo EJ, Camilleri M, Locke GR, Burton DD, Stephens DA,

Geno DM, et al. A community-based, controlled study of the

epidemiology and pathophysiology of dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:98596.

20. Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, Johnsson F, Junghard

O, Lauritsen K, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire

in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Scand J Gastroenterol 1998;33:10239.

21. Peura DA, Kovacs TO, Metz DC, Siepman N, Pilmer BL,

Talley NJ. Lansoprazole in the treatment of functional dyspepsia:

two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am

J Med 2004;116:7408.

22. Tack J, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Lee KJ, Sifrim D, Janssens J. Prevalence and symptomatic impact of non-erosive reflux disease in

functional dyspepsia. Gut 2005;10:13706.

23. Talley NJ, Meineche-Schmidt V, Pare P, Duckworth M, Raisanen

P, Pap A, et al. Efficacy of omeprazole in functional dyspepsia:

double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (the Bond

and Opera studies). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12:105565.

255

24. Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, Forman D, Talley NJ. The

efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology 2004;127:

132937.

25. Corsetti M, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Janssens J, Tack J. Impact

of coexisting irritable bowel syndrome on symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:11529.

26. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M,

et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006 Apr 19;(2):CD002096.

27. Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, Forman D, Talley NJ. The

efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology 2004;

127:132937.

28. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Innes M, Forman D.

Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2006 Oct 18;(4):CD001960.

29. Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Matsuo K, Kusunoki H, Kamada T, Ito

M, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of prokinetic agents in

patients with functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;

22:30410.

30. Hojo M, Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Ohkusa T, Nagahara A, Kawabe

M, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with antianxiety or

antidepressive agents: systematic review. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:

103642.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Gastrointestinal Health: The Self-Help Nutritional Program That Can Change the Lives of 80 Million AmericansDari EverandGastrointestinal Health: The Self-Help Nutritional Program That Can Change the Lives of 80 Million AmericansBelum ada peringkat

- Dyspepsia ReviewDokumen13 halamanDyspepsia ReviewalbertrianthoBelum ada peringkat

- Ibs Rome IIIDokumen9 halamanIbs Rome IIINguyễn Thái DuyBelum ada peringkat

- Therapeutic Strategies For Functional Dyspepsia and The Introduction of The Rome III Classification (2006)Dokumen12 halamanTherapeutic Strategies For Functional Dyspepsia and The Introduction of The Rome III Classification (2006)Yuriko AndreBelum ada peringkat

- GI - Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of BloatingDokumen11 halamanGI - Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of BloatingTriLightBelum ada peringkat

- Roma 4Dokumen15 halamanRoma 4RejaneGil GilBelum ada peringkat

- Functional (Non-Ulcer) Dyspepsia and Gastroesophageal Refl Ux Disease: One Not Two Diseases ?Dokumen3 halamanFunctional (Non-Ulcer) Dyspepsia and Gastroesophageal Refl Ux Disease: One Not Two Diseases ?Reynalth Andrew SinagaBelum ada peringkat

- Aziz 2018Dokumen9 halamanAziz 2018Elton MatsushimaBelum ada peringkat

- Functional GI Disorder Rome IVDokumen10 halamanFunctional GI Disorder Rome IVDr Reza ModarresBelum ada peringkat

- 2 PBDokumen6 halaman2 PBWildaS FatonahBelum ada peringkat

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokumen25 halamanNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptumam fazlurrahmanBelum ada peringkat

- Current Understanding of Pathogenesis ofDokumen8 halamanCurrent Understanding of Pathogenesis ofDominic SkskBelum ada peringkat

- Criterios Roma IV para IBSDokumen20 halamanCriterios Roma IV para IBSJose F MoralesBelum ada peringkat

- DyspepsiaDokumen7 halamanDyspepsiaFa'iz HeryotoBelum ada peringkat

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersDokumen3 halamanIrritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersdavpierBelum ada peringkat

- Nutrients 13 00575Dokumen19 halamanNutrients 13 00575dr.martynchukBelum ada peringkat

- ConstipacionDokumen31 halamanConstipacionargente23Belum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Reading Rome IVDokumen31 halamanJurnal Reading Rome IVrizki febrianBelum ada peringkat

- Functional DyspepsiaDokumen4 halamanFunctional DyspepsiaEasy Orient DewantariBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Diarrhea PDFDokumen5 halamanChronic Diarrhea PDFnaryBelum ada peringkat

- FAPS Sperber APT ProofDokumen11 halamanFAPS Sperber APT ProofAudricBelum ada peringkat

- Pemicu 2 GIT DevinDokumen93 halamanPemicu 2 GIT DevinDevin AlexanderBelum ada peringkat

- Functional Dyspepsia: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy: ReviewDokumen9 halamanFunctional Dyspepsia: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy: Reviewjenny puentesBelum ada peringkat

- Vignette UlfiDokumen12 halamanVignette UlfiHiya Ulfi MuniraBelum ada peringkat

- 功能性胃肠病(FGID)Dokumen58 halaman功能性胃肠病(FGID)Wai Kwong ChiuBelum ada peringkat

- Functional Dyspepsia: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology: Update ArticleDokumen5 halamanFunctional Dyspepsia: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology: Update ArticleDen BollongBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. S.P. RaiDokumen12 halamanDr. S.P. RaiSachin MundeBelum ada peringkat

- Diet IBS PDFDokumen31 halamanDiet IBS PDFIesanu MaraBelum ada peringkat

- Recurrent Abdominal Pain: C.H. SprayDokumen5 halamanRecurrent Abdominal Pain: C.H. SprayVilarTdBelum ada peringkat

- An Approach To The Patient With Chronic Undiagnosed Abdominal PainDokumen7 halamanAn Approach To The Patient With Chronic Undiagnosed Abdominal PainCarlos Arturo Caparo ChallcoBelum ada peringkat

- Organic Versus Functional: DyspepsiaDokumen16 halamanOrganic Versus Functional: DyspepsiahelenaBelum ada peringkat

- Dyspepsia: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkDokumen30 halamanDyspepsia: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkTruly Dian AnggrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Gastrointestinal PainDokumen16 halamanGastrointestinal PainntnquynhproBelum ada peringkat

- 10.1136@gutjnl 2019 318536Dokumen10 halaman10.1136@gutjnl 2019 318536IndahEPBelum ada peringkat

- Gastritis Bahasa InggrisDokumen7 halamanGastritis Bahasa InggrisNieq Cutex CelaluingindimandjaBelum ada peringkat

- Richter 2017Dokumen10 halamanRichter 2017Rachel RiosBelum ada peringkat

- Journal Reading: Therapeutic Strategies For Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based On PathophysiologyDokumen4 halamanJournal Reading: Therapeutic Strategies For Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based On PathophysiologyMuhamad IrsyadBelum ada peringkat

- DispepsiaDokumen37 halamanDispepsiaThomas KristiantoBelum ada peringkat

- CC New TranslateDokumen12 halamanCC New TranslateIrene MetekohyBelum ada peringkat

- Kasar Pkmrs BBBDokumen5 halamanKasar Pkmrs BBBIriamana Liasyarah MarudinBelum ada peringkat

- Plenary 2B Group 13Dokumen132 halamanPlenary 2B Group 13Obet Agung 天Belum ada peringkat

- Dross Man 2016Dokumen5 halamanDross Man 2016Erna MiraniBelum ada peringkat

- P1-5 Sugano - ICD-10 Classification of GastritisDokumen1 halamanP1-5 Sugano - ICD-10 Classification of GastritisBudiono WijayaBelum ada peringkat

- EditorialDokumen2 halamanEditorialRana1120Belum ada peringkat

- IBS - Beyond The Bowel: The Meaning of Co-Existing Medical ProblemsDokumen8 halamanIBS - Beyond The Bowel: The Meaning of Co-Existing Medical Problemsparthibanemails5779Belum ada peringkat

- Abdominal PainDokumen7 halamanAbdominal PainKartikey ChauhanBelum ada peringkat

- The Diagnosis and Treatment of Functional DyspepsiaDokumen20 halamanThe Diagnosis and Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia• Ridlo FebriansyahNonPrivacyBelum ada peringkat

- Bloque 2.1. Sleisenger and Fordtran'S - Section X - Chapter 122Dokumen23 halamanBloque 2.1. Sleisenger and Fordtran'S - Section X - Chapter 122Danisi ObregonBelum ada peringkat

- Almost All Irritable Bowel Syndromes Are Post-Infectious and Respond To Probiotics: Consensus IssuesDokumen4 halamanAlmost All Irritable Bowel Syndromes Are Post-Infectious and Respond To Probiotics: Consensus IssuesSyed AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- A Review Visceroptosis and Allied Abdominal ConditionsDokumen252 halamanA Review Visceroptosis and Allied Abdominal ConditionstenosceBelum ada peringkat

- ABDOMEN Agudo EnfrentamientoDokumen22 halamanABDOMEN Agudo Enfrentamientonicositja_vangoh91Belum ada peringkat

- SOAP Template0002Dokumen5 halamanSOAP Template0002kymhanBelum ada peringkat

- Diafragma y SiiDokumen9 halamanDiafragma y SiiFreddy SquellaBelum ada peringkat

- Quigley Ibs LectureDokumen6 halamanQuigley Ibs Lecturegbass_9Belum ada peringkat

- Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) : Prof DRDokumen21 halamanGastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) : Prof DRmohammed salahBelum ada peringkat

- Gastroenterology Function Bowel DisordersDokumen12 halamanGastroenterology Function Bowel DisordersKreshnik HAJDARIBelum ada peringkat

- Exploring The Spectrum of GERD: Myths and Realities: Special ArticleDokumen9 halamanExploring The Spectrum of GERD: Myths and Realities: Special ArticleedopriyantomoBelum ada peringkat

- ElsevierDokumen6 halamanElsevierNandaBelum ada peringkat

- Crohn's Disease: Natural Healing Forever, Without MedicationDari EverandCrohn's Disease: Natural Healing Forever, Without MedicationBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 111Dokumen6 halamanContentServer - Asp 111kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ANTIDIABETICSDokumen25 halamanANTIDIABETICSkookiescream100% (2)

- ContentServer - Asp 165Dokumen8 halamanContentServer - Asp 165kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 110Dokumen7 halamanContentServer - Asp 110kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- Hypercholesterolemia PDFDokumen7 halamanHypercholesterolemia PDFkookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- " Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics" "Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics"Dokumen7 halaman" Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics" "Hypercholesterolemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutics"kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- Ectopic Pregnancy: A ReviewDokumen12 halamanEctopic Pregnancy: A ReviewkookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 70Dokumen12 halamanContentServer - Asp 70kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 55Dokumen9 halamanContentServer - Asp 55kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 56Dokumen4 halamanContentServer - Asp 56kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 43Dokumen9 halamanContentServer - Asp 43kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- Karakteristik Penderita Penyakit Jantung Koroner Rawat Inap Di Rsu DR - Pirngadi Medan TAHUN 2003-2006Dokumen92 halamanKarakteristik Penderita Penyakit Jantung Koroner Rawat Inap Di Rsu DR - Pirngadi Medan TAHUN 2003-2006kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- ContentServer - Asp 62Dokumen9 halamanContentServer - Asp 62kookiescreamBelum ada peringkat

- Comprehensive Health Assessment of The Older Person in Health Aged CareDokumen2 halamanComprehensive Health Assessment of The Older Person in Health Aged CareMary Cleir CredoBelum ada peringkat

- Dhingra CH 5 SyarahDokumen86 halamanDhingra CH 5 Syarahgoblok goblokinBelum ada peringkat

- JAM2Dokumen80 halamanJAM2Nicoleta Florentina GhencianBelum ada peringkat

- Sleep and Pain ConstiousnesDokumen35 halamanSleep and Pain Constiousnestwity 1Belum ada peringkat

- NCP Self Care DeficitDokumen2 halamanNCP Self Care DeficitKasandra Dawn Moquia Beriso100% (3)

- SX2 V2LR DEKA WP Negosanti Nov13Dokumen4 halamanSX2 V2LR DEKA WP Negosanti Nov13DiegoSauvalleBelum ada peringkat

- The King's SpeechDokumen3 halamanThe King's SpeechAnap LigthBelum ada peringkat

- David Emerson RootDokumen4 halamanDavid Emerson RootMoshe RubinBelum ada peringkat

- PemivagakawagitonaDokumen2 halamanPemivagakawagitonanazeridewa64Belum ada peringkat

- QuizDokumen8 halamanQuizJohara Mae De RamaBelum ada peringkat

- Hijama PointsDokumen23 halamanHijama PointsShahbaz Ahmed100% (1)

- Cinema Narrative Therapy: Utilizing Family Films To Externalize Children's Problems' Brie Turns and Porter MaceyDokumen17 halamanCinema Narrative Therapy: Utilizing Family Films To Externalize Children's Problems' Brie Turns and Porter MaceyRupai SarkarBelum ada peringkat

- 2020 Participant Handbook Rwanda Training Program 1Dokumen17 halaman2020 Participant Handbook Rwanda Training Program 1sun angelaBelum ada peringkat

- Centric & Protrusive RecordDokumen51 halamanCentric & Protrusive RecordHadil AltilbaniBelum ada peringkat

- Aldinga Bay's Coastal Views August 2018Dokumen36 halamanAldinga Bay's Coastal Views August 2018Aldinga BayBelum ada peringkat

- Senior Project PaperDokumen7 halamanSenior Project Paperapi-283971814Belum ada peringkat

- Course Syllabus For Foundations of Nursing Practice Including Professional AdjustmentDokumen3 halamanCourse Syllabus For Foundations of Nursing Practice Including Professional AdjustmentPhilippineNursingDirectory.com100% (4)

- 2.5 Digoxin ToxicityDokumen8 halaman2.5 Digoxin ToxicityWaqar WikiBelum ada peringkat

- Nasogastric Tube InsertionDokumen17 halamanNasogastric Tube InsertionMichael Jude MedallaBelum ada peringkat

- MelanieresumeDokumen1 halamanMelanieresumeapi-253574700Belum ada peringkat

- Medhu Spa MenuDokumen24 halamanMedhu Spa Menumiki832Belum ada peringkat

- NCP LeukemiaDokumen3 halamanNCP LeukemiaLuige Avila100% (5)

- NCP 2Dokumen3 halamanNCP 2klawdin100% (1)

- Marketing I - Price ListDokumen3 halamanMarketing I - Price ListthimotiusBelum ada peringkat

- Causes and Treatment Outcome of Mechanical Bowel Obstruction in North Eastern NigeriaDokumen3 halamanCauses and Treatment Outcome of Mechanical Bowel Obstruction in North Eastern NigeriakeithBelum ada peringkat

- Sadism and FrotteurismDokumen2 halamanSadism and FrotteurismYvonne Niña Aranton100% (1)

- Graviola - Secret Cancer CureDokumen10 halamanGraviola - Secret Cancer CureRegina E.H.Ariel100% (3)

- Control Charts Healthcare Setting MMPDokumen6 halamanControl Charts Healthcare Setting MMPAndrés AvilésBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Leadership and Management ExamsDokumen4 halamanNursing Leadership and Management ExamsMarisol Jane Jomaya67% (9)

- Anxiety ManagementDokumen2 halamanAnxiety ManagementYanira RiveraBelum ada peringkat