Strength Training

Diunggah oleh

Aditiya MahantHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Strength Training

Diunggah oleh

Aditiya MahantHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Family and Consumer Sciences

FSFCS33

Increasing Physical Activity as We Age

Strength Training

LaVona Traywick, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Gerontology

Arkansas Is

Our Campus

Visit our web site at:

http://www.uaex.edu

Introduction

Strength trainingalso

referred to as resistance training

or weightliftingis part of a

comprehensive exercise routine

which includes endurance or

aerobic activity, balance or

stability training and flexibility or

stretching exercises. Strength

training is when we work the

skeletal muscles of our bodies

harder than they are used to,

usually through free weights,

resistance bands/tubes or weight

machines. Strength training

increases strength, anaerobic

endurance and muscle mass. The

goal of strength training is to

grow stronger.

As we age, muscle strength

declines. Humans can lose up to

one-half of their strength and

muscle mass between the ages of

25 and 80 years. Part of this

decline is due to the biology of

aging; however, the other part of

this decline is due to inactivity.

What is promising is that progres

sive strength training for adults

and senior adults not only

prevents muscle loss but also

increases strength and muscle

mass, similar to what is observed

in young adults. Participating in

strength training has many

positive benefits for our health.

Why Is Strength Training

Important?

Strength training has many

important benefits. In addition to

increased strength and muscle

mass, strength training also

increases bone density. Strength

training exercises have been

shown to reduce the risk for

numerous chronic diseases

including diabetes, heart disease,

osteoporosis and arthritis. On top

of that, strength training has been

shown to have many positive

effects on psychological health

such as reduced depression,

improved sleep and greater sense

of well-being. Furthermore,

strength training is helpful in

maintaining a healthy weight.

Exercise

Recommendations

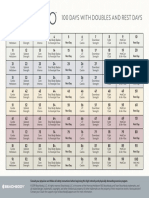

Adults and senior adults

should do strength training exer

cises that work all major muscle

groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen,

chest, shoulders and arms) two to

three days a week with a rest

day in between the strength

training sessions. This rest day

does not mean to forgo doing the

other types of exercisesit is

specific for strength training.

Examples of strength training

exercises include lifting or pushing

free weights, pulling resistance

bands and using strength-training

equipment at a fitness center or

gym. In some cases, strength

University of Arkansas, United States Department of Agriculture, and County Governments Cooperating

training can include lifting your own body

weight, such as with push-ups or squats.

Categories of Strength Training

Strength training exercises can be classified

into three categories:

Isometricsometimes referred to as

staticis where no movement occurs; an

action in which the muscle develops tension,

but does not shorten.

Example: Attempting to pick up the chair you

are sitting in or standing with each hand on

opposite sides of a doorway attempting to

push down the walls.

Isotonicsometimes referred to as dynamic;

contractions in which a muscle shortens

against a constant load or tension, resulting

in movement.

Example: Using free weights (such as

barbells and dumbbells) or commercial

weight machines. Isotonic exercises also

include variable-resistance exercises such as

using stretch bands and exercise tubes as

well as commercial devices.

Isokineticthe exertion of force at a constant

speed; action in which the rate of movement

is constantly maintained through a specific

range of motion even though maximal force

is exerted.

Example: Performing the exercise on

commercial isokinetic devices. The machine is

programmed to move at a certain speed so it

will vary its resistance against you to main

tain that speed. This means if you push

against the machine hard, it will give back a

lot of resistance to maintain the speed at

which it was told to go.

Although all forms of strength training are

beneficial, performing isotonic exercises using

free weights (dumbbells and/or barbells) is

recommended over the other methods. Research

studies have shown that, compared to other

methods of weight training, free weights produce

greater strength gains during short-term train

ing periods, provide greater movement abilities

and involve both balance and stabilizing factors.

The disadvantages of free weights include the

possibility of injury (such as dropping the weight

on your toe), needing a spotter for heavy

weights and learning the proper lifting tech

nique. That said, it is better to do some kind of

strength training than nothing at all.

Progressive Strength Training

The most common form of strength training

is weightlifting using free weights or various

types of weight machines. In order to improve

strength, weight training must push the muscles

beyond what they are used tocalled overload

principalby periodically increasing the amount

of weight or resistance used in that particular

exercise. This concept is referred to as Progres

sive Resistance Exercise and is the basis for most

strength training programs.

How does progressive strength training work?

When you first begin, you should start exercising

with weights that you can lift at least ten times

with only moderate difficulty. If you cannot do at

least 8 repetitions, the weight you are using is too

heavy and you need to use a lighter weight. If you

can do over 12 repetitions, the weight you are

using is too light and you need to use a heavier

weight. After two weeks of strength training, you

should reassess the difficulty of each exercise with

your current level of weights.

For example, you may have started doing the

biceps curl with a 3-pound weight. By the end of

the second week, the exercise has become too

easy for you, and you should increase your

weights to a 4- or 5-pound dumbbell. At the end

of the fourth week, you once again reassess. You

may stay with the 5-pound weight one more

week or you may move up to a 6- or 8-pound

weight. A good way to check to see if you are

ready to increase your dumbbell weight or if you

should stay the same is to do the exercise with

your current weight and count your repetitions.

If you can easily lift the current weight dumbbell

through the full range of motion and in proper

form more than 12 times, you should increase

your dumbbell weights by 1 to 3 pounds and see

how the exercise feels at the new weight level.

With the new weight, you should be able to have

correct form for at least 8 repetitions.

When performing strength training exercises,

you should only use equipment intended for

exercise. There is an increased risk of injury and

improper form when using household items as

weights. It is also important to note that you will

need different size weights for different exer

cises. For example, a person may be able to

perform a wrist curl with a 3-pound weight, the

biceps curl with an 8-pound weight and the

shoulder press with a 5-pound weight.

Biology of Strength Training

As we age, muscle strength declines. Most of

this decline happens after the age of fifty. This

loss of strength is mainly from inactivitynot

using our muscles. Another part of the muscle

strength decline is due to the aging process. This

loss of strength due to aging actually occurs at

the motor neuron level. The motor neuron is what

gives the message from your brain through the

central nervous system to the muscle telling it to

contract and move. This decline in the motor

neuron is a neurological change that occurs with

aging. This is important to note because whatever

affects the motor neuron affects the muscle fibers

attached. So a decline in the motor neuron unit

leads to a decrease in muscle fibers (both Type I

and Type II muscle fibers). The loss of muscle

fibers from those individual motor neuron units

results in less available force for a muscle

contraction when that motor neuron is stimu

lated. Once the muscle contraction mechanism is

impaired, there is a loss of strength and power.

The good news is that regular, progressive

strength training can reverse the loss of muscle

strength due to the biology of aging.

Strength training not only increases our

muscle mass, it also increases our bone density.

Bones respond to strength training by increasing

their bone density. The bone grows stronger or

denser in response to the forces associated with

the muscle contraction. As the muscles get

stronger, the bone gets strong too. How does this

work? Bone is made up of a configuration of bone

fibers, blood vessels and lymphatics which is

called osteoid. Bone responds to stress (such as

strength training) and disuse (as in our sedentary

lifestyles) by increasing the osteoid in areas that

are subject to stress and reducing it in areas

where it is no longer needed. Increased bone

density is called sclerosis. Sclerosis of the bone

can result from strength training exercise. It is

important to note that bone adaptations

are exercise specific. For example, a lower body

exercisesuch as a squatwill strengthen the

leg bones but will not strengthen the bones in the

upper body.

Sample Exercises

Be sure to warm up your muscles before you begin strength training. (For more information

about the warm-up, see FSFCS34, Stretching.) The number of times you perform the exercise is

called the repetitions or reps. The number of times each group of repetitions is performed is called

the set. For all the following exercises, strive for 2 sets of 10 repetitions. In other words, perform the

exercise 10 times, rest for a minute, then do the exercise 10 more times.

Note: When using dumbbells, do not work with two different size weights per hand. Work with the

weight of the weaker arm until you can safely progress to the next higher poundage.

Overhead Press, also known as the Military

Press. (Works primarily the shoulder muscles

with some arm muscles.)

1. Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart

and knees straight but not locked.

2. Hold a dumbbell in each hand at shoulder

height with palms facing forward. See

Figure 1: Overhead Press Starting Position.

3. Slowly raise both arms up over your head,

keeping your elbows slightly bent and in line

with your body.

4. Pause for a breath, approximately 1 second.

See Figure 2: Overhead Press.

5.

Lower the dumbbells back to your shoulders.

Note: If you are unable to reach your arms over

your head due to surgery or other medical

precautions, you can do the side arm raise as an

alternate shoulder exercise. The overhead press

and the side arm raise both work the shoulder

muscle. You do not need to do them both.

Figure 1. Overhead press

starting position.

Figure 2. Overhead press.

Side Arm Raise With Bent Arm (Works the

shoulders.)

1. This exercise can be performed standing or

seated. Keep your feet shoulder-width apart

with feet flat on the floor.

2. Holding a dumbbell in each hand, keep your

arms by your side, bend your elbows to a

90-degree angle. See Figure 3: Side Arm Raise

Starting Position and Figure 4: Side Arm Raise

Starting Position, Side View.

3. Keeping the bend in your elbows, raise both

arms to the side, shoulder height. See Figure 5:

Side Arm Raise and Figure 6: Side Arm Raise,

Side View.

Figure 3. Side arm raise

starting position.

Figure 4. Side arm

raise starting position,

side view.

Figure 5. Side arm raise.

Figure 6. Side arm raise,

side view.

Figure 7. Biceps curl

starting position.

Figure 8. Biceps curl.

Figure 9. Seated biceps

curl starting position.

Figure 10. Seated

biceps curl.

4. Slowly lower your arms back to your side.

Biceps Curl (Works the biceps muscle, which is the

front muscle of the upper arm)

1. Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and

knees straight but not locked.

2. Hold weights straight down at your side, palms

facing inward. See Figure 7: Biceps Curl

Starting Position.

3. As you slowly bend your elbows to lift the

weights towards you shoulders, rotate the

weight so that your palms are facing your

shoulders. See Figure 8: Biceps Curl.

4. Slowly lower the weights, rotating your arms

back to the starting position.

Note: As a variation of the biceps curl, you can do

this exercise seated and one arm at a time. See

Figure 9: Seated Biceps Curl Starting Position and

Figure 10: Seated Biceps Curl.

Triceps Kickback (Works the triceps muscle

group, which is the back of the upper arm.)

1. This exercise can be performed standing or

seated. Keep your feet shoulder-width apart

with feet flat on the floor.

2. Hinge at your hips, lowering your torso to

form a 45-degree angle. Be sure to lift your

chest and tighten your abdominal muscles.

Your upper arms should be lifted to the level

of your back with your elbows bent. Keep

your upper arms and elbow close to your

body. See Figure 11: Triceps Kickback

Starting Position.

Figure 11. Triceps

kickback starting position.

Figure 12. Triceps kickback.

3. Slowly extend the lower part of your arm

until it forms a straight line with the upper

arm. Avoid locking out your elbow joint while

keeping your wrist straight. See Figure 12:

Triceps Kickback.

4. Keeping your upper arms and elbows close to

your torso, lower the dumbbells to the

starting position in a controlled motion.

Wide Leg Squat (Works the front, back and

inner thigh muscles as well as the buttocks.)

1. Stand with your feet slightly greater than

shoulder-width apart, crossing your arms in

front of your chest. See Figure 13: Wide Leg

Squat Starting Position and Figure 14: Wide

Leg Squat Starting Position, Side View.

2. Keeping your chest lifted and your back,

neck and head in a straight line, slowly

lower yourself back to a seated position.

See Figure 15: Wide Leg Squat and

Figure 16: Wide Leg Squat, Side View.

Figure 13. Wide leg

squat starting position.

Figure 14. Wide leg

squat starting position,

side view.

Figure 15. Wide leg

squat.

Figure 16. Wide leg

squat, side view.

3. Stand up slowly, pushing up from your heels

through your lower legs, thighs, hips and

buttocks. Be sure your knees do not move

in front of your toes.

Note: When you are first learning the wide leg

squat, you can stand behind a high back chair

and hold on for balance.

References

2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: Be Active, Healthy

and Happy! (2008). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services; Government Printing Office.

ODPHP Publication No. U0036.

Exercise and Physical Activity: Your Guide from the National

Institute on Aging (2009). National Institute on Aging and the

National Institutes of Health. Government Printing Office.

Publication No. 09-4258.

Baker, K. et al. (2001). The efficacy of home-based progressive

strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis:

a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rheumatology

28(7) 1655-65.

Castaneda, C. et al. (2002). A randomized control trail of progressive

resistance exercise training in older adults with type 2

diabetes. Diabetes Care 25(12).

Fiatarone, M.A. et al. (1990). High-intensity strength training in

nonagenarians: effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 263:3029-34.

Nelson, M., and R. Seguin. (2003). The Strong Women Program/

The Strong Women Tool Kit. (Boston, Massachusetts).

Tufts University.

Powers, S. K. H., and Edward T. Howley. (2001). Exercise Physiology:

Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance (Fourth

Edition ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Printed by University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service Printing Services.

LAVONA TRAYWICK, Ph.D., is assistant professor - gerontology with

the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture in Little Rock.

FSFCS33-PD-5-09N

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and

June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Director, Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas. The

Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service offers its programs to all eligible

persons regardless of race, color, national origin, religion, gender, age,

disability, marital or veteran status, or any other legally protected status,

and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Train Like A ChampionDokumen29 halamanTrain Like A Championadam100% (5)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Track your strength gains with The Juggernaut Method 2.0 workout trackerDokumen7 halamanTrack your strength gains with The Juggernaut Method 2.0 workout trackerPhil EichBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Performer 25Dokumen19 halamanPerformer 25joasobralBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Physical Fitness 1 Jeopardy WebDokumen27 halamanPhysical Fitness 1 Jeopardy WebAidan NicholsBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- PEDokumen3 halamanPEDeianeira HerondaleBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Beautiful Body GuideDokumen145 halamanBeautiful Body GuideMichelle RdvBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Physical Fitness Checklist: Name: - Course & SectionDokumen3 halamanPhysical Fitness Checklist: Name: - Course & SectionCharlesBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Pe and Health 11Dokumen2 halamanPe and Health 11paolo vinuyaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- 5 Components of Fitness LessonDokumen6 halaman5 Components of Fitness LessonMariniel Gomez Lacaran80% (59)

- Texas StoneManDokumen2 halamanTexas StoneMantomegatherion77Belum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Pilates Matwork Teacher TrainingDokumen6 halamanPilates Matwork Teacher TrainingDance For Fitness With PoojaBelum ada peringkat

- Basic MovementsDokumen19 halamanBasic MovementsEric marasiganBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Score Card Forfun2Dokumen1 halamanScore Card Forfun2felipeformentaoBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- MM100 Workout CalendarDokumen1 halamanMM100 Workout CalendarlinsimsBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Workout Tips & Motivation Secrets From SWEAT TrainersDokumen15 halamanWorkout Tips & Motivation Secrets From SWEAT TrainersTony BjornsenBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- PhysioEx Exercise 2 Activity 7Dokumen5 halamanPhysioEx Exercise 2 Activity 7Emi Camacho100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Physical and Physiological Characteristics PDFDokumen5 halamanPhysical and Physiological Characteristics PDFDanilo Pereira Dos SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- College of Education Physical Activity Towards Health and Fitness 1Dokumen11 halamanCollege of Education Physical Activity Towards Health and Fitness 1Marcelo SakitingBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient Olympic GamesDokumen6 halamanAncient Olympic GamesMelina LorenzoBelum ada peringkat

- Zainab Osama Year 13A - PE Project - Long JumpDokumen10 halamanZainab Osama Year 13A - PE Project - Long JumpZAINAB OSAMABelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Weight Training: 2 Books Bundle - Strength Training Program 101 + Strength Training Nutrition 101Dokumen154 halamanWeight Training: 2 Books Bundle - Strength Training Program 101 + Strength Training Nutrition 101Ulas SaracBelum ada peringkat

- Canadian Sport For Life PosterDokumen2 halamanCanadian Sport For Life PosterSpeed Skating Canada - Patinage de vitesse CanadaBelum ada peringkat

- CORE Complex Training ProgramsDokumen10 halamanCORE Complex Training ProgramsDarwis Chin AbdullahBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Vin Diesel WorkoutDokumen2 halamanVin Diesel WorkoutChris Darryn RandallBelum ada peringkat

- My Strength ProgressDokumen30 halamanMy Strength ProgressNeal StarbirdBelum ada peringkat

- 18-19 Cehs Track and Field ScheduleDokumen1 halaman18-19 Cehs Track and Field Scheduleapi-336551541Belum ada peringkat

- Calisthenics Training Plan enDokumen7 halamanCalisthenics Training Plan enGustavo LapoBelum ada peringkat

- A Historical Perspective of The Paralympic GamesDokumen4 halamanA Historical Perspective of The Paralympic GamesTatiane HilgembergBelum ada peringkat

- MI40 X Workout Sheets 2 Graduate Intermediate PDFDokumen49 halamanMI40 X Workout Sheets 2 Graduate Intermediate PDFdeviangelmkdBelum ada peringkat

- Aquatics Pt. 1Dokumen44 halamanAquatics Pt. 1Dwayne Arlo CincoBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)