What Is Time

Diunggah oleh

Sylvia Cheung0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

41 tayangan4 halamanExplains what time is within the context of Bhagava Gita

Judul Asli

What is Time

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniExplains what time is within the context of Bhagava Gita

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

41 tayangan4 halamanWhat Is Time

Diunggah oleh

Sylvia CheungExplains what time is within the context of Bhagava Gita

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 4

C H A P T E l

ON E

..

Th e AN C I E N T A R T of

TI M E C H E A T I N G

The Supreme Lord said: uTime I am, the great destroyer

of the worlds; even without you, will all the people here,

all the fighters who took positions on opposite sides,

be engaged in destroying.

-Bhagavad Gita 11.32

oga practitioners have known about time travel since

ancient times, and many still practice it today. Yoga is a

system of practice that is part art, part philosophy, and

part science. It is a hands-on method for ennobling one's life,

finding purpose in it, and going beyond the everyday illusions

that inundate us all. According to traditional Indian philosophy,

the yoga system is divided into two principal parts- hatha yoga

and raja yoga-with many minor divisions within each . 1 Hatha

yoga deals principally with physiology, with a view to establish

ing health and training the mind and body. Raj a yoga is a means

to control the mind itself by following a rigorous method laid

down by adepts long ago. The word yoga shows up in several

contexts in Hindu thought and has a number of meanings. Yoga

is the name of one of the six original systems of Hindu philoso

phy, which provides the philosophical basis for yoga as pre

sented by the ancient sage Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. In the

11

C H AP T E R O N E

Sutras, Patanjali sets forth ashtanga yoga (literally, the eight

limbed practice ) , which is now generally referred to as raj a

yoga. Again, the most famous Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita,

talks about karma yoga, bhakti yoga, and jnana yoga- three

pathways for attaining enlightenment. The Gita also speaks of

kriya yoga, as do the Yoga Sutras. When you compare them, you

find they complement each other, leading adepts to say that hatha

is kriya is raja.

Yoga as both a practice and a system implies a concept of

time summed up in the Sanskrit word samsara. Samsara signifies

conditioned existence, boundedness-the yoking of spirit to spa

tial and temporal confinement. As Georg Feuerstein, a noted

scholar and teacher of yoga philosophy, points out, "Above all . . .

Samsara is time. "2 Feuerstein explains that the literal meaning

of samsara is flowing together-a perpetual flux of things and

events producing consequences of causal relationships. As the

late Gilda Radner used to remind us on the television show

" S aturday Night Live, " this flowing together can produce unex

pected and undesired consequences-if it isn't one thing or

another, " it 's always something. " This flowing together of things

and events has a counterpart in quantum physics, and it is vital to

how the mind " creates" time and the appearance of objective

events. We will look at this in detail in the upcoming chapters,

particularly chapters 8 and 9.

But samsara also refers to something that the Western mind,

with its " linear" view of time, does not consider. This is the idea

of the wheel of existence-that the soul experiences endless

rounds of birth, life, death, and rebirth, set in motion by causal

links created in past lives . It turns out that, from a quantum

physics point of view, these cycles can be experienced by the

time traveler through recognition of the role played by the ego

mind to " anchor" experience-literally bind it into time pro

viding an active focal point or ego.

Samsara is also a term for maya, or illusion-the persistent

beliefs that bind us to space and time so we participate in the flow

of these perpetual cycles rather than escaping from them. This

12

T H E ANC I E NT A R T O F T r M E C H E AT IN G

view of life taught by ancient adepts, too, resonates with findings

in quantum physics, as we shall see in chapter 8.

Many ancient hymns tell us that time-the past, present, and

future-is the progenitor of the cosmos and that time itself is the

child of consciousness. Contained within this ancient wisdom is

a secret: that it is possible through technique to cheat time-in

other words, to travel through time, and even to reach the shores

of timelessness. Again, quantum physics agrees, and it tells us

how we can draw a map of these shores so the traveler sees what

they may look like. I find it striking that modern physics posits

the existence of a timeless, spaceless realm of existence without

which much of modern physics would make little sense, nor

would it connect with reality as we perceive it.

Well and good, you may say, but what does this have to do

with time travel? Digging deeper into these ancient texts, we find

that they say time and space are products of the mind and do

not exist independent of it. The principles of quantum physics,

remarkably, tell us the same thing. This is an extraordinary key.

The trick to going outside the confines of space and time is to

reach beyond their source-the mind itself. Paradoxically, we need

a theoretical picture created by the mind to understand what it

means to reach beyond the mind. We also need a form of practice.

To make time travel real, not j ust a theoretical exercise,

requires a way of slipping around the corner, peeking under the

screen, so to speak, where our usual motion picture of reality is

projected. The ancient Vedas referred to this behind-the-scenes

look at creation as kala-vancana, literally, " time-cheating. "3 It is

possible, they say, to escape the space-time illusion of samsara

the projections of the mind itself, which turns out be our own

memory in disguise-and cheat time, that is, travel through time.

In the coming chapters, we will examine how we think of time

and how quantum physics and consciousness are related. But

first let's look more closely at what one of the ancient Indian

texts has to say.

13

C HA P T E R O N E

TH E B HA GAVAD G I TA

In the early part of the first millennium

BCE,

Indian philosophers

found evidence for the beginnings of what we today call the

perennial philosophy. It can be stated in three sentences:

1 . An infinite, unchanging reality exists hidden behind the

illusion of ceaseless change.

2. This infinite, unchanging reality lies at the core of every

being and is the substratum of the personality.

3 . Life has one main purpose: to experience this one reality

to discover God while living on earth.

One of the ancient texts in which these principles are set

forth and discussed is the Bhagavad Gita.4 The spiritual wisdom

of the Gita is delivered in the midst of the most terrible of all

possible human situations: warfare-literally, on the battlefield

itself. On the eve of combat, the prince Arjuna loses his nerve

and in desperation turns to his charioteer, Krishna, asking him

what to do. But Krishna is no ordinary horse-and-cart driver; he

is a direct incarnation of God, and he responds to Arjuna in

seven hundred stanzas of sublime instruction that includes a

divine mystical revelation.5 He explains to Arjuna the nature of

the soul and the nature of the timeless, spaceless, changeless infi

nite reality and explains that they are not different.

The Gita does not lead the reader from one stage of spiritual

development to another, but starts with the conclusion. Krishna

says right away that the immortal soul is unchanging and always

p resent and-important for our purpose-that the passing

moments of time are illusionary. The soul wears the body as a

garment-to be discarded when it becomes worn. Thus the soul

travels from body to body, casting aside the old bodies to take on

new ones. Just as death is certain for the living, rebirth is certain

for the dead. But, Krishna reassures Arjuna, the soul is eternal,

not subject to life and death. Arjuna will not be able to perceive

14

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- DR Jeremiah Revelation Prophecy Chart PDFDokumen2 halamanDR Jeremiah Revelation Prophecy Chart PDFkoinoniabcn93% (14)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1091)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Space Time and ConsciousnessDokumen10 halamanSpace Time and ConsciousnessSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Tinnitus - How An Alternative Remedy Became The Only Weapon Against The RingingDokumen13 halamanTinnitus - How An Alternative Remedy Became The Only Weapon Against The RingingSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Exploring Negative Space: Log Cross Ratio 2iDokumen11 halamanExploring Negative Space: Log Cross Ratio 2iSylvia Cheung100% (2)

- Cost Accounting and Management Essentials You Always Wanted To Know: 4th EditionDokumen21 halamanCost Accounting and Management Essentials You Always Wanted To Know: 4th EditionVibrant Publishers100% (1)

- Process Audit Manual 030404Dokumen48 halamanProcess Audit Manual 030404azadsingh1Belum ada peringkat

- What Is TimeDokumen8 halamanWhat Is TimeSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Informatics and Consciousness TransferDokumen13 halamanInformatics and Consciousness TransferSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- How Common Indian People Take Investment Decisions Exploring Aspects of Behavioral Economics in IndiaDokumen3 halamanHow Common Indian People Take Investment Decisions Exploring Aspects of Behavioral Economics in IndiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Bay Marshalling BoxesDokumen4 halamanBay Marshalling BoxesSimbu ArasanBelum ada peringkat

- Reincarnated As A Sword Volume 12Dokumen263 halamanReincarnated As A Sword Volume 12Phil100% (1)

- Is 456 - 2016 4th Amendment Plain and Reinforced Concrete - Code of Practice - Civil4MDokumen3 halamanIs 456 - 2016 4th Amendment Plain and Reinforced Concrete - Code of Practice - Civil4Mvasudeo_ee0% (1)

- 1st Year Unit 7 Writing A Letter About A CelebrationDokumen2 halaman1st Year Unit 7 Writing A Letter About A CelebrationmlooooolBelum ada peringkat

- Minipro Anemia Kelompok 1Dokumen62 halamanMinipro Anemia Kelompok 1Vicia GloriaBelum ada peringkat

- Karma: What It Is, What It Isn't, Why It Matters. by Traleg KyabgonDokumen2 halamanKarma: What It Is, What It Isn't, Why It Matters. by Traleg KyabgonSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Multiple RegressionDokumen32 halamanMultiple RegressionSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Quantum Pure PossibilitiesDokumen44 halamanQuantum Pure PossibilitiesSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Something From NothingDokumen6 halamanSomething From NothingSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Emptiness and Category TheoryDokumen14 halamanEmptiness and Category TheorySylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Exploring Data Patterns: Time SeriesDokumen20 halamanExploring Data Patterns: Time SeriesSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Prewhitening With SPSSDokumen4 halamanPrewhitening With SPSSSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Capital Asset Pricing ModelDokumen1 halamanCapital Asset Pricing ModelSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Testing Two Related MeansDokumen19 halamanTesting Two Related MeansSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Being & Field TheoryDokumen5 halamanBeing & Field TheorySylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Decomposition of Time SeriesDokumen14 halamanDecomposition of Time SeriesSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of Contingency TablesDokumen34 halamanAnalysis of Contingency TablesSylvia CheungBelum ada peringkat

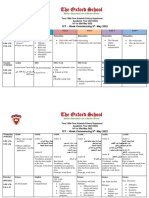

- Term 3 Mid-Term Assessment ScheduleDokumen9 halamanTerm 3 Mid-Term Assessment ScheduleRabia MoeedBelum ada peringkat

- Synthesis of Bicyclo (2.2.l) Heptene Diels-Alder AdductDokumen2 halamanSynthesis of Bicyclo (2.2.l) Heptene Diels-Alder AdductJacqueline FSBelum ada peringkat

- PPSC Lecturer Mathematics 2004Dokumen1 halamanPPSC Lecturer Mathematics 2004Sadia ahmadBelum ada peringkat

- Cargill Web Application Scanning ReportDokumen27 halamanCargill Web Application Scanning ReportHari KingBelum ada peringkat

- Perceived Impact of Community Policing On Crime Prevention and Public Safety in Ozamiz CityDokumen7 halamanPerceived Impact of Community Policing On Crime Prevention and Public Safety in Ozamiz Cityjabezgaming02Belum ada peringkat

- Voloxal TabletsDokumen9 halamanVoloxal Tabletselcapitano vegetaBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Reliability Eng - 2021 - Saha - Parametric Inference of The Loss Based Index CPM For Normal DistributionDokumen27 halamanQuality Reliability Eng - 2021 - Saha - Parametric Inference of The Loss Based Index CPM For Normal DistributionShweta SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Antenna and Propagation: Introduction + Basic ConceptsDokumen19 halamanAntenna and Propagation: Introduction + Basic Conceptsanon_584636667Belum ada peringkat

- NameDokumen16 halamanNameAfro BertBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsDokumen17 halamanIndian Standard: General Technical Delivery Requirements FOR Steel and Steel ProductsPermeshwara Nand Bhatt100% (1)

- CatalysisDokumen50 halamanCatalysisnagendra_rdBelum ada peringkat

- Karrnathi Undead P2Dokumen2 halamanKarrnathi Undead P2Monjis MonjasBelum ada peringkat

- Giving Counsel PDFDokumen42 halamanGiving Counsel PDFPaul ChungBelum ada peringkat

- Knowledge Versus OpinionDokumen20 halamanKnowledge Versus OpinionShumaila HameedBelum ada peringkat

- Subordinating Clause - Kelompok 7Dokumen6 halamanSubordinating Clause - Kelompok 7Jon CamBelum ada peringkat

- Picaresque Novel B. A. Part 1 EnglishDokumen3 halamanPicaresque Novel B. A. Part 1 EnglishIshan KashyapBelum ada peringkat

- CaseLaw RundownDokumen1 halamanCaseLaw RundownTrent WallaceBelum ada peringkat

- Continuum Mechanics - Wikipedia PDFDokumen11 halamanContinuum Mechanics - Wikipedia PDFjflksdfjlkaBelum ada peringkat

- Survey Questionnaire FsDokumen6 halamanSurvey Questionnaire FsHezell Leah ZaragosaBelum ada peringkat

- 434-Article Text-2946-1-10-20201113Dokumen9 halaman434-Article Text-2946-1-10-20201113Rian Armansyah ManggeBelum ada peringkat

- Mergers and Acquisitions of Hindalco and NovelisDokumen35 halamanMergers and Acquisitions of Hindalco and Novelisashukejriwal007Belum ada peringkat