NPPV Como Metodo de Decanulacion en Niños PCCM Enero 2010

Diunggah oleh

juliasimonassiDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

NPPV Como Metodo de Decanulacion en Niños PCCM Enero 2010

Diunggah oleh

juliasimonassiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Continuing Medical Education Article

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation avoids recannulation and

facilitates early weaning from tracheotomy in children*

Brigitte Fauroux, MD, PhD; Nicolas Leboulanger, MD; Gilles Roger, MD; Françoise Denoyelle, MD, PhD;

Arnaud Picard, MD, PhD; Erea-Noel Garabedian, MD; Guillaume Aubertin, MD; Annick Clément, MD, PhD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After participating in this educational activity, the participant should be better able to:

1. Understand the use of the technique of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in children with tracheotomy.

2. Recognize factors favorably influenced by noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in children with tracheotomy.

3. Understand the factors associated with the successful transition to noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in children

with tracheotomy.

Unless otherwise noted below, each faculty or staff’s spouse/life partner (if any) has nothing to disclose.

The authors have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with or interests in any commercial companies

pertaining to this educational activity.

All faculty and staff in a position to control the content of this CME activity have disclosed that they have no financial

relationship with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Visit the Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Web site (www.pccmjournal.org) for information on obtaining continuing medical

education credit.

Objective: To show that noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation tients who failed repeated decannulation trials because of poor

by means of a nasal mask may avoid recannulation after decannu- clinical tolerance of tracheal tube removal or tube closure during

lation and facilitate early decannulation. sleep.

Design: Retrospective cohort study. Measurements and Main Results: After noninvasive positive-pres-

Setting: Ear-nose-and-throat and pulmonary department of a pe- sure ventilation acclimatization, decannulation was performed with

diatric university hospital. success in all patients. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation was

Patients: The data from 15 patients (age ⴝ 2–12 yrs) who needed associated with an improvement in nocturnal gas exchange and

a tracheotomy for upper airway obstruction (n ⴝ 13), congenital marked clinical improvement in their obstructive sleep apnea symp-

diaphragmatic hypoplasia (n ⴝ 1), or lung disease (n ⴝ 1) were toms. None of the 15 patients needed tracheal recannulation. Nonin-

analyzed. Four patients received also nocturnal invasive ventilatory vasive positive-pressure ventilation could be withdrawn in six pa-

support for associated lung disease (n ⴝ 3) or congenital diaphrag- tients after 2 yrs to 8.5 yrs. The other nine patients still receive

matic hypoplasia (n ⴝ 1). Decannulation was proposed in all patients noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation after 1 yr to 6 yrs.

because endoscopic evaluation showed sufficient upper airway pa- Conclusions: In selected patients with upper airway obstruction or

tency and normal nocturnal gas exchange with a small size closed lung disease, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation may repre-

tracheal tube, but obstructive airway symptoms occurred either im- sent a valuable tool to treat the recurrence of obstructive symptoms

mediately or with delay after decannulation without noninvasive after decannulation and may facilitate early weaning from tracheot-

positive-pressure ventilation. omy in children who failed repeated decannulation trials. (Pediatr Crit

Interventions: In nine patients, noninvasive positive-pressure ven- Care Med 2010; 11:31–37)

tilation was started after recurrence of obstructive symptoms after a KEY WORDS: upper airway; decannulation; congenital airway abnor-

delay of 1 to 48 mos after a successful immediate decannulation. malities; noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation; child

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation was anticipated in six pa-

*See also p. 146. Plastic Surgery and Maxillo-Facial Department, Hopital ADEP Assistance, and Université Pierre et Marie Curie-

Professor (BF, GA, AC), Pediatric Pulmonary, Armand-Trousseau, Paris, France; and Professor Paris 6 (BF).

Hopital Armand Trousseau, Paris, France; Associate (E-NG), Chief of Department (E-NG), Hopital Armand- For information regarding this article, E-mail:

Surgeon (NL, GR), Otolaryagology-Head & Neck Sur- Trousseau, Universitie Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, brigitte.fauroux@trs.aphp.fr

gery Department, Hopital Armand-Trousseau, Univer- France; and Professor (GA), Pediatric Pulmonary, Ho- Copyright © 2010 by the Society of Critical Care

sitie Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France; Associate pital Armand Trousseau, Paris, France. Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Inten-

Professor (FD), Otolaryagology-Head & Neck Surgery The research is supported, in part, by the Associ- sive and Critical Care Societies

Department, Hopital Armand Trousseau, Universitie ation Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Assis-

Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France; Professor (AP), tance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, INSERM, Legs Poix, DOI: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b80ab4

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1 31

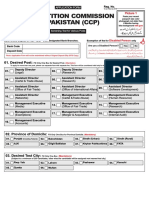

C ongenital or acquired upper children with chronic lung disease, such Fifteen tracheotomized patients (8.8%)

airway abnormalities are com- as cystic fibrosis (17–19). In recent years, have been treated with NPPV during the study

mon in children. Laryngeal we have used NPPV in patients who have period and are analyzed in the present report.

abnormalities (such as laryn- had their tracheotomy removed and sub- Written approval for care was provided by all

gomalacia, subglottic stenosis, or vocal sequently developed recurrent airway ob- parents and the analysis of the data was ap-

cord paralysis), tracheal abnormalities struction. We then used NPPV to facili- proved by the local ethical committee.

(such as tracheomalacia or tracheal ste- tate early decannulation in patients who In a first approach, NPPV was used to treat

nosis) as well as Pierre Robin syndrome failed repeated decannulation trials. In the recurrence of obstructive symptoms after

an immediate successful decannulation (de-

may be responsible for severe upper air- the present study, we relate our experi-

layed NPPV group). Patients with tracheoto-

way obstruction that may persist despite ence over the last 12 yrs.

mies undergo regular video-endoscopic evalu-

medical and surgical treatment. In these

ation of the upper airways under general

cases, tracheotomy is indicated to pre-

MATERIALS AND METHODS anesthesia (spontaneous breathing and as-

vent potentially serious complications, sisted ventilation). Decannulation is proposed

such as airway obstruction and sudden A tracheotomy was performed in 171 pa- when the following criteria are fulfilled:

death (1, 2), pulmonary hypertension and tients during the 12-yr study period (1996 –

cor pulmonale (2, 3), failure to thrive (4, 2008) (Fig. 1). Seventy-one patients (42%) 1. Sufficient airway patency during spontane-

5), and neurocognitive dysfunction with have been decannulated successfully and re- ous breathing in the operating room was

the risk of intellectual impairment (6). In mained asymptomatic on systematic follow-up evaluated by endoscopy and reflected by

case of severe lung disease, tracheotomy examinations. Sixty patients are still tracheot- normal breathing and normal gas exchange

may be indicated to allow invasive venti- omized and undergo regular evaluations. in room air.

lation in order to improve alveolar venti- Nineteen of these 60 patients could be future 2. Adequate airway patency during sleep was

lation (7). candidates for decannulation because a suffi- assessed by the absence of obstructive

However, tracheotomy is associated cient improvement in upper airway obstruc- symptoms, such as stridor, agitation,

with a significant morbidity and discom- tion may be expected in the future. The arousals, night sweats, and the absence of

fort and may impair normal development other patients have too severe upper airway nocturnal hypoxemia (⬍5 consecutive

and, particularly, language development obstruction or associated morbid condi- mins with a pulse oximetry [SpO2] ⬍90%)

tions. Nineteen patients returned to their with hypercapnia (transcutaneous carbon

(8, 9). Discomfort and social life and fam-

ily disruption are common in patients

primary hospital and have been lost to fol- dioxide [PtcCO2] ⬎50 torr, ⬎6,7 kPa) while

low-up. Six patients with severe underlying sleeping in room air with a closed tracheal

with a tracheotomy (10). A recent study

conditions died. tube. Before this test, the tracheal tube is

has shown that parents caring for chil-

changed for a smaller model to favor easier

dren with tracheotomy tubes experience

breathing during nocturnal sleep.

significant caregiver burden and that the

mental health status for an adult caring All patients who fulfilled these criteria

for a child with a tracheotomy tube is were decannulated without NPPV. A regular

significantly reduced (10). Although tra- 3-mo follow-up was systematically performed

cheotomized children may be safely dis- with clinical examination, endoscopic evalua-

charged home after careful family educa- tions when indicated, and nocturnal gas ex-

tion and training, home treatment may change recordings at least every 6 mos.

be difficult or even unfeasible for some In a second approach, we used NPPV to

families (7, 11). Thus, whenever possible, facilitate early weaning from tracheostomy

decannulation should be proposed as (immediate NPPV group). In these patients,

soon as possible. But decannulation fail- airway patency with a closed smaller tube was

ure is not uncommon, and apart from the not sufficient during nocturnal sleep as re-

medical consequences, the psychological flected by obstructive symptoms (described

consequences on the child and the family above) and abnormal nocturnal gas exchange

are important to consider. Nursing staff’s in room air with at least 5 consecutive mins

observations of restlessness, anxiety, and with a SpO2 ⬍90% and/or a PtcCO2 ⬎50 torr

depression appeared more frequently in (⬎6,7 kPa). In this situation, or after previous

children who failed decannulation (12). several failed decannulation attempts, NPPV

was proposed before decannulation.

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventila-

In this immediate NPPV group, the decan-

tion (NPPV), which consists of the deliv-

nulation procedure was as follows. The first

ery of positive airway pressure by means

step consisted of the acclimatization of the

of a nasal mask, has been shown to re- patient to the nasal mask only, without the

duce the work of breathing in children ventilator. This step took between 2 to 15 days,

with upper airway obstruction associated depending on the patient’s age, and his/her

with alveolar hypoventilation (13–16). medical and psychological history. Then,

NPPV, by maintaining the patency of the when the patient accepted to wear the nasal

upper airways during the breathing cycle, mask with the headgear, NPPV without seda-

allows an increase in tidal volume and tion was tried for short periods, lasting 2 to 5

minute ventilation, which translates into mins, which were repeated during daytime.

an improvement in gas exchange (15, 16). Figure 1. Flow chart of diaphragm of patients. When daytime tolerance exceeded 15 contin-

NPPV has also demonstrated its benefit in NPPV, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. uous mins, NPPV was tried during the night as

32 Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1

the tracheal tube was closed. Because of the ing the acclimatization to NPPV. Sleep studies hypercapnia (Table 2). These obstructive

partial airway obstruction due to the presence looked for obstructive apnea, which was de- symptoms were explained by an increase

of the tube, the inspiratory and expiratory fined as the absence of air flow with continued of pharyngolaryngeal hypotonia or the re-

NPPV pressures were set 2 cm H2O above the chest-wall and abdominal movement for at currence of the primary disorder for

levels that would have been chosen without least two breaths (21, 22). Hypopnea was de- which no satisfactory surgical interven-

the presence of the tube. Overnight SpO2, fined as a decrease in nasal flow of ⱖ50% with tion could be proposed. NPPV was initi-

PtcO2, and PtcCO2 recordings were systemati- a corresponding decrease in SpO2 ⱖ4% and/or ated to avoid recannulation. Nocturnal

cally performed. At initiation, NPPV was per- with associated arousal. The apnea index and bilevel positive-pressure ventilation was

formed at night and during daytime with three the hypopnea index were defined as the num-

performed with inspiratory pressures of 6

to four breaks of 2 to 3 hrs. But within 1 wk, bers of apnea and hypopneas per hour of total

to 10 cm H2O and expiratory pressures of

all the patients were able to use NPPV exclu- sleep time. A desaturation was defined as a

4 to 6 cm H2O. The five youngest patients

sively during sleep, at night in all the patients decrease of SpO2 ⱖ4% below baseline and the

desaturation index was calculated as the num-

were equipped with a custom-made

and during daytime naps in the youngest pa-

ber of desaturations per hour of total sleep mask, whereas the four older patients

tients. The tracheal tube was then removed

time (21, 22). Evaluation of diurnal gas ex- used a commercially available mask. The

and NPPV settings were adjusted to obtain a

change was assessed by arterialized capillary daytime and nocturnal gas exchange in-

normal breathing pattern without stridor and

blood gases in the morning, after a night of dices and sleep parameters exhibited a

adequate gas exchange, as defined by the ab-

sence of nocturnal hypoxemia (⬍5 consecu- NPPV (23). Initially, the tracheal stoma was trend toward improvement but because

tive mins with an SpO2 ⬍90%) and hypercap- occluded by a sticking plaster. The number of of the small number of patients, the dif-

nia (no periods with a PtcCO2 ⬎50 torr [⬎6,7 patients who needed a surgical closure of the ferences did not reach statistical signifi-

kPa]). The acceptance and optimal setting of tracheal stoma was recorded. cance (Table 2). All the patients were dis-

NPPV lasted 3 to 15 more days, depending on Discharge to home with NPPV was allowed charged home. A surgical closure of the

the age of patient, his/her medical history, when the following criteria were fulfilled: tracheal stoma was required in four pa-

anxiety, and psychological stress. tients (patients 1, 2, 8, and 9). NPPV

● Ability to sleep at least 5 hrs with NPPV; could be definitely withdrawn in three

NPPV was always performed by pressure-

● Absence of nocturnal hypoxemia or hyper- patients, after 2 yrs in patients 2 and 5,

controlled ventilators (Harmony or Synchrony

capnia while on NPPV without supplemen- and after 8.5 yrs in patient 8. At follow-

(Respironics, Craquefou, France), VPAP 3ST

tal oxygen;

or STA (Resmed, Saint Priest, France), Vivo 40 up, none of the patients needed a recan-

● Parents and family educated to NPPV.

(Breas Medical, Saint Priest, France), or nulation and none of the patients died.

Knightstar (Tyco Healthcare, Elancourt,

France), delivering bilevel positive airway RESULTS Immediate NPPV Group

pressure by means of a commercially available

(Respironics, Resmed or Fisher Paykel nasal Delayed NPPV Group The immediate NPPV group com-

masks), or custom-made nasal mask. These prised six patients (Table 1). In four of

custom-made masks were composed of a ther- The delayed NPPV group comprised these patients, tracheotomy was per-

moformable plastic frame (VT Plastics, Gen- nine patients (Table 1). In seven patients formed before 3 mos of age because of

nevilliers, France) with an interior coverage of (patients 1 to 7), tracheotomy was per- severe upper airway obstruction in the

either self-sticking foam (Adhesia Laboratoire, formed before 6 mos of age, because of neonatal period. The two other patients

Mulhouse, France) or a protection and com- vocal cord paralysis (which was always were tracheotomized at ages 1.5 yrs and

fort gel (Adhesia Laboratoire, Mulhouse, associated with another cause of airway 2.7 yrs because of mandibular hypoplasia

France). The nasal mask was connected to an obstruction) in four patients (patients 2, (patient 14) and chronic respiratory in-

expiratory valve and a nonrebreathing circuit 3, 6, and 7), Treacher-Collins syndrome sufficiency related to an acute respiratory

by a plastic tube of an inner diameter of 22 in one patient (patient 1), congenital pa- distress syndrome of unknown origin (pa-

mm, which was fixed on the mask by an au- ralysis of the diaphragm in one patient tient 15). This latter patient received noc-

topolymerizable resin (Orthoresin, Dentsply,

(patient 4), and cystic lymphangioma in turnal pressure-controlled ventilation be-

Weybridge, United Kingdom). The masks were

one patient (patient 5). Patients 4 and 6 cause of his associated lung disease as

modeled on plaster phantoms corresponding

received nocturnal NPPV on the tracheal well as patient 10 because of associated

to the age and the physiognomy of the patient.

tube before decannulation because of di- bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In these

Bedside adjustments were then realized, if

aphragmatic paralysis and associated two patients, NPPV was started before

necessary, by thermoforming the plastic frame

to obtain the best comfort with minimal leaks

bronchopulmonary dysplasia, respec- decannulation because of the need to

(20). Custom-made masks were used in case of tively. Immediate decannulation was well continue nocturnal ventilatory support.

age ⬍2 yrs, facial deformity, and/or intoler- tolerated by all patients, without clinical Once the decision had been made to at-

ance of an industrial mask (20). Inspiratory symptoms of upper airway obstruction, tempt tracheotomy removal, a smaller

pressures of 6 to 10 cm H2O and expiratory nocturnal desaturations, or hypercapnia tube was placed to facilitate spontaneous

pressures of 4 to 6 cm H2O were used, with a as previously defined. However, after a breathing. In the four patients who were

ramp when available and a back-up rate of 2 to delay of 1 to 48 mos, all patients devel- not on long-term invasive ventilation, de-

5 breaths below the patient’s spontaneous oped symptoms of obstructive sleep ap- cannulation without NPPV was not pos-

breathing rate. nea with stridor, night sweats and arous- sible because of nocturnal hypoventila-

Nocturnal gas exchange was routinely eval- als, daytime fatigue, and change in mood tion due to upper airway obstruction. All

uated by oxygen and CO2 recording, either by and attention. Nocturnal SpO2, PtCO2, and patients developed clinical symptoms of

the Tina monitor (Tina, Radiometer, Copen- PtcCO2 recordings in room air showed the upper airway obstruction with stridor,

hague, Denmark), or by the SenTec Digital presence of apneas and hypopneas, asso- chest retractions, and night sweats, asso-

Monitor (SenTec, Therwil, Switzerland) dur- ciated with periods of desaturation and ciated with periods exceeding 5 continu-

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1 33

Table 1. Description of the patients

Age at Age at NPPV Delay

Patient Gender Diagnosis Tracheotomy Detubation (yrs) (mos) Outcome

Delayed NPPV

group

1 female Treacher-Collins 1 mo 2.5 6 on NPPV since 1 mo

syndrome

2 female Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 1 mo 2.5 4 successful NPPV withdrawal at

tracheomalacia age 5, now 7.5 yrs old

3 male Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 3 mos 11 48 still on NPPV at age 18

polymalformation

4 male Congenital 3 mos 5.7 12 still on NPPV at age 12

diaphragmatic

hypoplasia #

5 female Cystic lymphangioma 6 mos 2 1 successful NPPV withdrawal at

age 4, now 11 yrs old

6 male Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 6 mos 2 1 still on NPPV at age 4

BPD #

7 male Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 6 mos 10 6 still on NPPV at age 11

multiple congenital

anomalies

8 male Laryngeal cleft 1 yr 3 6 successful NPPV withdrawal at

age 12, now 13 yrs old

9 female Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 6.5 yrs 10.5 9 still on NPPV at age 12

cerebral tumor

Immediate NPPV

group

10 male Pierre Robin sequence 1 mo 3.5 0 successful NPPV withdrawal at

⫹ BPD # age 7, now 8 yrs old

11 female Cystic lymphangioma 1 mo 12 0 still on NPPV at age 17

⫹ mandibular

hypoplasia

12 male Laryngeal cleft grade 2 mos 2.5 0 successful NPPV withdrawal at

IV age 5, now 8 yrs old

13 male Vocal cord paralysis ⫹ 3 mos 6 0 successful NPPV withdrawal at

tracheomalacia age 8, now 8.5 yrs old

14 female Mandibular hypoplasia 1.5 yrs 9 0 still on NPPV at age 14

15 male ARDS sequelae # 2.7 yrs 7 0 still on NPPV at age 9

NPPV, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; #, patients receiving

nocturnal positive-pressure ventilation on the tracheal tube before decannulation.

ous mins with a SpO2 ⬍90% and a PtcCO2 care facility were able to return to their support. The use of bilevel positive end-

⬎50 torr (⬎6,7 kPa) during tracheal tube families. After decannulation, all the pa- expiratory pressure by means of a nasal

closure and/or removal trials. In these tients experienced improvements in lan- mask was associated with an improve-

patients, no surgical option was available guage and development. Initially, the tra- ment of nocturnal gas exchange in all

to facilitate decannulation without seri- cheal stoma was occluded by a plastic patients and during follow-up, none of

ous drawbacks, such as an increase in the sticker, but a secondary surgical closure the patients needed recannulation.

risk of false passages. Previous attempts of the tracheal stoma was necessary in all NPPV has been shown to be an alter-

of decannulation without NPPV had been patients. Three patients could be weaned native to invasive ventilation in selected

undertaken at least two times in all six from NPPV after 2 yrs to 3 yrs and three patients with neuromuscular disease,

patients over long periods (mean pe- others were still on NPPV at ages 9, 14, managed by highly skilled teams. In ad-

riod ⫽ 14.3 mos; range ⫽ 6 –32 mos) and 17 yrs. None of the patients died.

olescents and young adults with Duch-

without success. Mean age at decannula-

enne muscular dystrophy, NPPV by

tion in these patients was 6.7 yrs DISCUSSION means of a nasal mask during the night

(range ⫽ 2.5–12 yrs). The daytime and

nocturnal gas exchange indices and sleep This study shows that NPPV is able to and a mouthpiece during the day, associ-

parameters with nocturnal NPPV were treat successfully the recurrence of ob- ated with cough-assisted techniques, may

within the normal range (Table 2). structive airway disorders after tracheot- allow extubation or decannulation and

The three youngest patients were omy weaning in children. But, most im- prolong survival in well-trained and

equipped with custom-made masks and portantly, we show for the first time that highly qualified teams (24, 25). Even in

the three older patients with commer- NPPV may facilitate decannulation in young infants with spinal muscular atro-

cially available nasal masks. All the pa- children who failed repeated decannula- phy Type I, a noninvasive respiratory

tients were discharged home and the tion trials. Tracheotomy weaning could management approach may be successful

three patients who were in a transitional only be achieved with immediate NPPV in selected cases, with an improvement in

34 Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1

Table 2. Daytime and nocturnal gas exchange indices press their will, refused the eventuality of

a recannulation.

Delayed NPPV Group n ⫽ 9

We present here a series of 14 patients

Immediate NPPV

Normal Valuesa Before NPPV With NPPV Group n ⫽ 6 with upper airway disease and one patient

with lung disease in whom NPPV was able

Daytime to facilitate decannulation or treat ob-

parameters struction recurrence. Several requisites

PaO2, torr 80 ⫾ 10 78 ⫾ 8 73 ⫾ 2 82 ⫾ 7 must be fulfilled for NPPV to be success-

PaCO2, torr 35 ⫾ 10 37 ⫾ 3 39 ⫾ 3 40 ⫾ 4 ful. First, endoscopic evaluation should

Nocturnal

parameters

show a sufficient airway patency, allow-

Apnea index ⬍1 3⫾3 0.0 ⫾ 0.0 0.2 ⫾ 0.4 ing acceptable tolerance of spontaneous

Hypopnea ⬍1 37 ⫾ 39 0.6 ⫾ 1.3 0.4 ⫾ 0.5 breathing without a tracheal tube. Be-

index cause of lack of objective measurable cri-

% of time with ⱖ99% 54 ⫾ 33 69 ⫾ 29 36 ⫾ 29 teria to estimate airway caliber in young

SpO2 ⱖ95% children, this decision relies on the sub-

% of time with ⱕ1% 29 ⫾ 21 29 ⫾ 13 63 ⫾ 16

SpO2 91%–

jective estimation of the airway patency

94% by an experienced pediatric ear-nose-

% of time with 0% 16 ⫾ 34 2⫾6 1⫾1 throat surgeon.

SpO2 ⱕ90% Second, NPPV in this age group re-

Desaturation ⬍1 38 ⫾ 35 25 ⫾ 22 22 ⫾ 14 quires some technical requisites. The

index choice of the interface is problematic in

PtcO2 min, torr ⱖ70 62 ⫾ 27 69 ⫾ 11 63 ⫾ 11

PtcCO2 max, ⱕ50 51 ⫾ 8 49 ⫾ 3 48 ⫾ 4

young children (20). To our knowledge,

torr no adequate commercial nasal masks are

Delta PtcCO2 ⱕ10 15 ⫾ 8 11 ⫾ 3 9⫾3 available for children weighing ⬍10 kg.

max, torr These young children need thus custom-

made masks, which require an experi-

NPPV, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation; PaO2, partial arterial oxygen pressure; PaCO2, enced and motivated pediatric maxillofa-

partial arterial carbon dioxide pressure; SpO2, pulse oximetry; PtcO2 min, minimum transcutaneous cial team. Because of facial growth and

oxygen pressure; PtcCO2 max, maximum transcutaneous carbon dioxide pressure; delta PtcCO2 max,

potential side effects, such as skin injury

maximum awake/night change of transcutaneous carbon dioxide pressure.

a

American Thoracic Society (21) and Montgomery-Downs et al (22).

and facial deformity, a close follow-up of

these masks is absolutely necessary (20).

With this maxillofacial monitoring, no

medical condition and quality of life for randomized, controlled trial but the fea- significant skin or facial side effects were

the child and his/her family (26, 27). sibility of such a study may be extremely observed in the patients included in the

To our knowledge, information re- difficult because of practical and ethical present study.

garding the use of NPPV to facilitate ex- issues. Even if large series have reported Finally, the psychological aspect is of

tubation or tracheotomy weaning in a low occurrence rate of tracheotomy- paramount importance. A tracheotomy is

other pediatric diseases is lacking. Indi- related mortality and morbidity, severe an invasive procedure, associated with re-

cations for tracheotomies in children in- complications may occur during the can- current invasive maneuvers, such as as-

clude airway obstruction, inadequate air- nulation period, such as tube obstruction piration, tube removal, and change, and,

way protection, chronic lung disease, or dislocation, accidental decannulation, as a consequence, hospital visits and hos-

neuromuscular weakness, and central hy- or pneumothorax (7, 31–34). Long-term pitalizations. All these children have se-

poventilation (7). All these conditions complications include tracheal stenosis, vere, and often multiple medical disor-

may be managed by NPPV, if the patient stomal narrowing, and recurrent lung in- ders, which contribute to anxiety, pain,

has an adequate respiratory autonomy, and psychological stress, both for the

fections occurring in 10% to 40% of pa-

allowing NPPV to be used preferentially child and his/her family. This may explain

tients (7, 33, 34). There is also evidence

at night. Interestingly, regular use of why some children resist any procedure

that children with tracheotomies are at

NPPV at night was associated with an involving the face or the upper airway. In

risk for delays in receptive and expressive

improvement in daytime spontaneous more than half of the children in the

breathing and gas exchange, as observed language development as well in deficits present study, acclimatization to the na-

in children with other conditions, such as in oral/vocal speech and voice production sal mask took ⬎1 wk, which is twice as

neuromuscular disease (28 –30). As such, (35–37). NPPV, as a noninvasive tech- long as our experience with children who

NPPV could be proposed to a selected nique, is not associated with these nu- did not have a prior tracheotomy. The

group of tracheotomized patients to facil- merous side effects. Importantly, unex- active role of the parents, but also the

itate decannulation. pected readmission rate may reach 63% nurses, psychologists, and school teach-

Our protocol is based on the assump- in some series of children with tracheot- ers are of great help in such situations.

tion that long-term use of NPPV is asso- omy (7), whereas none of the 15 patients Encouragements and positive rewards

ciated with a better quality of life for the reported in the present study required were used by the medical team and family

patient and his/her family and fewer side readmission to the hospital for an acute to help the child to accept NPPV. One

effects than a prolonged tracheotomy. To upper or lower respiratory tract problem child, who underwent tracheotomy in the

our knowledge, NPPV has not been com- during the follow-up. Importantly, all the neonatal period for congenital myasthe-

pared with tracheotomy in a prospective, families and patients, when able to ex- nia which was diagnosed only at the age

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1 35

of 4 yrs, never accepted the nasal mask CONCLUSIONS creasing safety and decreasing cost. Int J Pedi-

and NPPV. His spontaneous sleep without atr Otorhinolaryngol 1997; 39:111–118

a tracheotomy and ventilatory support To our knowledge, we report here a 13. Waters WA, Everett FM, Bruderer JW, et al:

was acceptable after decannulation but first experience of successful use of NPPV Obstructive sleep apnea: The use of nasal

to treat recurrent respiratory obstruction CPAP in 80 children. Am J Respir Crit Care

after 1 yr, he required 5 days of invasive

after decannulation and facilitate decan- Med 1995; 152:780 –785

ventilation for an acute viral lower airway 14. Guilleminault C, Pelayo R, Clerk A, et al:

infection. It is highly possible that, in this nulation in young children with severe

Home nasal continuous positive airway pres-

neuromuscular patient, the long-term upper airway obstruction or lung disease. sure in infants with sleep-disordered breath-

use of NPPV would have been able to The increasing use of NPPV in children, ing. J Pediatr 1995; 127:905–912

prevent acute invasive ventilatory sup- both in the acute (40) and chronic setting 15. Fauroux B, Pigeot J, Polkey MI, et al: Chronic

port (38, 39). These medical, technical, (41, 42), should be extended also to a stridor caused by laryngomalacia in children.

and psychological requirements may ex- selected group of tracheotomized pa- Work of breathing and effects of noninvasive

plain why NPPV is not considered as a tients, to improve the quality of life for ventilatory assistance. Am J Respir Crit Care

routine procedure to facilitate decannu- the child and his/her family. Med 2001; 164:1874 –1878

16. Essouri S, Nicot F, Clement A, et al: Nonin-

lation in young children.

vasive positive pressure ventilation in infants

We acknowledge that the patients of ACKNOWLEDGMENT with upper airway obstruction: Comparison

the present study had particularly severe of continuous and bilevel positive pressure.

upper airway obstruction that required We thank Emmanuelle Cohen for her Intensive Care Med 2005; 31:574 –580

maintenance of the tracheal tube to a very excellent technical assistance. 17. Fauroux B, Pigeot J, Isabey D, et al: In vivo

advanced age (⬎6 yrs of age) whereas de- physiological comparison of two ventilators

cannulation for usual upper airway ob- used for domiciliary ventilation in children

struction is generally achieved before the REFERENCES with cystic fibrosis. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:

age of 4 yrs. At that advanced age, our 2097–2105

patients did not tolerate decannulation 1. Sivan Y, Ben-Ari J, Schonfeld TM: Laryngomala- 18. Fauroux B, Nicot F, Essouri S, et al: Setting

cia: A cause for early near miss for SIDS. Intern of pressure support in young patients with

without NPPV even after several trials, re-

J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1991; 21:59–64 cystic fibrosis. Eur Resp J 2004; 24:624 – 630

flecting the severity of the residual obstruc-

2. Marcus CL, Crockett DM, Davidson Ward SL: 19. Fauroux B, Louis B, Hart N, et al: The effect

tion that NPPV was able to improve. of back-up rate during non-invasive ventila-

Evaluation of epiglottoplasty as treatment for se-

An important observation from the de- vere laryngomalacia. J Pediatr 1990; 117: tion in young patients with cystic fibrosis.

layed NPPV group is that patients with 706–710 Intensive Care Med 2004; 30:673– 681

severe upper airway obstruction need a 3. Naiboglu B, Deveci S, Duman D, et al: Effect 20. Fauroux B, Lavis JF, Nicot F, et al: Facial side

close and prolonged medical follow-up of upper airway obstruction on pulmonary effects during noninvasive positive pressure

after decannulation. Alveolar hypoventi- arterial pressure in children. Int J Pediatr ventilation in children. Intensive Care Med

lation could recur as long as 48 mos after Otorhinolaryngol 2008; 72:1425–1429 2005; 31:965–969

decannulation (patient 3). Apart from 4. Marcus CL, Carroll JL, Koerner CB, et al: 21. American Thoracic Society: Standards and

medical and endoscopic examination, Determinants of growth in children with the indications for cardiopulmonary sleep stud-

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Pediatr ies in children. Am J Resp Crit Care Med

careful attention must be paid to sleep-

1994; 125:556 –562 1996; 153:866 – 878

disordered breathing and sleep-related 22. Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, Gul-

5. Roger G, Denoyelle F, Triglia JM, et al: Se-

problems. Ideally, all those patients vere laryngomalacia: surgical indications and liver TE, et al: Polysomnographic character-

should have a complete polysomnogra- results in 115 patients. Laryngoscope 1995; istics in normal preschool and early school-

phy, which is the gold standard for the 105:1111–1117 aged children. Pediatrics 2006; 117:741–753

diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing. 6. Kheirandish L, Gozal D: Neurocognitive dys- 23. Gaultier C, Boulé M, Allaire Y, et al: Deter-

Such a complete evaluation was not pos- function in children with sleep disorders. mination of capillary oxygen tension in in-

sible in the immediate NPPV group be- Dev Sci 2006; 9:388 –399 fants and children: Assessment of methodol-

cause of the unstable clinical condition of 7. Graf JM, Montagnino BA, Hueckel R, et al: ogy and normal values during growth. Bull

the patients. In the delayed NPPV group, Pediatric tracheostomies: A recent experi- Europ Physiopath Resp 1978; 14:287–294

ence from one academic center. Pediatr Crit 24. Gomez-Merino E, Bach JR: Duchenne mus-

some patients had a polysomnography

Care Med 2008; 9:96 –100 cular dystrophy: Prolongation of life by non-

but others, because of time and practical invasive ventilation and mechanically as-

8. Dubey SP, Garap JP: Pediatric tracheostomy:

constraints, had only an overnight re- An analysis of 40 cases. J Laryngol Otol 1999; sisted coughing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil

cording of gas exchange. However, these 113:645– 651 2002; 81:411– 415

recordings were always sufficiently ab- 9. Wetmore RF, Marsh RR, Thompson ME, 25. Toussaint M, Steens M, Wasteels G, et al:

normal to institute NPPV without delay. et al: Pediatric tracheostomy: A changing Diurnal ventilation via mouthpiece: Survival

Finally, the use of NPPV as an alter- procedure? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1999; in end-stage Duchenne patients. Eur Resp J

native to recannulation and as a weaning 108:695– 699 2006; 28:549 –555

tool for tracheotomized patients raises 10. Hartnick CJ, Bissell C, Parsons SK: The impact 26. Bach JR, Niranjan V: Spinal muscular atrophy

the question of the optimal indications of pediatric tracheotomy on parental caregiver type I: A noninvasive respiratory management

burden and health status. Arch Otolaryngol approach. Chest 2000; 117:1100–1105

for tracheotomy in children. The useful-

Head Neck Surg 2003; 129:1065–1069 27. Bach JR: The use of mechanical ventilation is

ness of NPPV as a first-line treatment in

11. Ruben RJ, Newton L, Jornsay D, et al: Home care appropriate in children with genetically proven

selected patients with severe upper air- of the pediatric patient with a tracheotomy. Ann spinal muscular atrophy type 1: The motion for.

way obstruction, who have sufficient air- Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1982; 91:633–640 Paediatr Respir Rev 2008; 9:45–50; quiz 50; dis-

way patency when awake during daytime 12. Waddell A, Appleford R, Dunning C, et al: The cussion 55–56

and who need positive pressure only dur- Great Ormond Street protocol for ward decan- 28. Simonds AK, Ward S, Heather S, et al: Out-

ing sleep, is worthy of evaluation. nulation of children with tracheostomy: In- come of paediatric domiciliary mask ventila-

36 Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1

tion in neuromuscular and skeletal disease. cheostomy: A 13-year experience. Pediatr dren with neuromuscular disease. Neurology

Eur Respir J 2000; 16:476 – 481 Surg Int 2004; 20:695– 698 2007; 68:198 –201

29. Mellies U, Ragette R, Dohna Schwake C, et 34. Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, et al: Pedi- 39. Dohna-Schwake C, Podlewski P, Voit T, et al:

al: Long-term noninvasive ventilation in atric tracheotomy: 17 year review. Int J Pediatr Non-invasive ventilation reduces respiratory

children and adolescents with neuromus- Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71:1829 –1835 tract infections in children with neuromus-

cular disorders. Eur Respir J 2003; 22:631– 35. Simon B, Handler SD: The speech pathologist cular disorders. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008; 43:

636 and management of children with tracheosto- 67–71

30. Annane D, Orlikowski D, Chevret S, et al: mies. J Otolaryngol 1981; 10:440 – 448 40. Essouri S, Chevret L, Durand P, et al: Nonin-

Nocturnal mechanical ventilation for 36. Kaslon KW, Stein RE: Chronic pediatric tra- vasive positive pressure ventilation: Five years

chronic hypoventilation in patients with cheotomy: Assessment and implications for ha- of experience in a pediatric intensive care unit.

neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Co- bilitation of voice, speech and language in Pediatr Crit Care Med 2006; 7:329 –334

chrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 4:CD001941 young children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 41. Fauroux B, Sardet A, Foret D: Home treat-

31. Simma B, Spehler D, Burger R, et al: Trache- 1985; 9:165–171 ment for chronic respiratory failure in chil-

ostomy in children. Eur J Pediatr 1994; 153: 37. Arvedson JC, Brodsky L: Pediatric tracheot- dren: A prospective study. Eur Resp J 1995;

291–296 omy referrals to speech-language pathology 8:2062–2066

32. Carr MM, Poje CP, Kingston L, et al: Com- in a children’s hospital. Int J Pediatr Otorhi- 42. Fauroux B, Boffa C, Desguerre I, et al: Long-

plications in pediatric tracheostomies. La- nolaryngol 1992; 23:237–243 term noninvasive mechanical ventilation for

ryngoscope 2001; 111:1925–1928 38. Young HK, Lowe A, Fitzgerald DA, et al: children at home: A national survey. Pediatr

33. Alladi A, Rao S, Das K, et al: Pediatric tra- Outcome of noninvasive ventilation in chil- Pulmonol 2003; 35:119 –125

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010 Vol. 11, No. 1 37

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- MentoringDokumen20 halamanMentoringShruthi Raghavendra100% (1)

- Card Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentDokumen9 halamanCard Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentKeesha Athena Villamil - CabrerosBelum ada peringkat

- Global Economy and Market IntegrationDokumen6 halamanGlobal Economy and Market IntegrationJoy SanatnderBelum ada peringkat

- MODULE 2 e LearningDokumen70 halamanMODULE 2 e Learningseena15Belum ada peringkat

- Pestle of South AfricaDokumen8 halamanPestle of South AfricaSanket Borhade100% (1)

- Mecánica Respiratoria: Signos en El Circuito VentilatorioDokumen13 halamanMecánica Respiratoria: Signos en El Circuito VentilatoriojuliasimonassiBelum ada peringkat

- Extubacion en Pacientes Con Enfermedades NeuromuscularesDokumen9 halamanExtubacion en Pacientes Con Enfermedades NeuromuscularesjuliasimonassiBelum ada peringkat

- Should Patients Be Able To Follow Commands Prior To IonDokumen10 halamanShould Patients Be Able To Follow Commands Prior To IonjuliasimonassiBelum ada peringkat

- Predictors of Extubation Success and Failure in Mechanically Ventilated Infants and ChildrenDokumen6 halamanPredictors of Extubation Success and Failure in Mechanically Ventilated Infants and ChildrenTomy AjBelum ada peringkat

- Manual BiPAP SynchronyDokumen62 halamanManual BiPAP Synchronyadpodesta5Belum ada peringkat

- User Guide Cough AssistDokumen20 halamanUser Guide Cough AssistjuliasimonassiBelum ada peringkat

- Second Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)Dokumen217 halamanSecond Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)jessica coronelBelum ada peringkat

- Davison 2012Dokumen14 halamanDavison 2012Angie Marcela Marulanda MenesesBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Development: High School Department Culminating Performance TaskDokumen3 halamanPersonal Development: High School Department Culminating Performance TaskLLYSTER VON CLYDE SUMODEBILABelum ada peringkat

- IB Grade Boundaries May 2016Dokumen63 halamanIB Grade Boundaries May 2016kostasBelum ada peringkat

- Principles & Procedures of Materials DevelopmentDokumen66 halamanPrinciples & Procedures of Materials DevelopmenteunsakuzBelum ada peringkat

- Voice Over Script For Pilot TestingDokumen2 halamanVoice Over Script For Pilot TestingRichelle Anne Tecson ApitanBelum ada peringkat

- ICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalDokumen203 halamanICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalZe OmBelum ada peringkat

- Devendra Bhaskar House No.180 Block-A Green Park Colony Near ABES College Chipiyana VillageDokumen3 halamanDevendra Bhaskar House No.180 Block-A Green Park Colony Near ABES College Chipiyana VillageSimran TrivediBelum ada peringkat

- Unpacking Learning CompetenciesDokumen16 halamanUnpacking Learning CompetenciesAngela BonaobraBelum ada peringkat

- Osborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and AnxietyDokumen21 halamanOsborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and Anxietystefa BaccarelliBelum ada peringkat

- Main Ideas in Paragraphs (Getting The Big Ideas) : Professor Karin S. AlderferDokumen52 halamanMain Ideas in Paragraphs (Getting The Big Ideas) : Professor Karin S. AlderferEnglish HudBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter1 Education and SocietyDokumen13 halamanChapter1 Education and SocietyChry Curly RatanakBelum ada peringkat

- Activity in TC 3 - 7.12.21Dokumen5 halamanActivity in TC 3 - 7.12.21Nica LagrimasBelum ada peringkat

- 3 20 Usmeno I Pismeno IzrazavanjeDokumen5 halaman3 20 Usmeno I Pismeno Izrazavanjeoptionality458Belum ada peringkat

- IE468 Multi Criteria Decision MakingDokumen2 halamanIE468 Multi Criteria Decision MakingloshidhBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Assurance in BacteriologyDokumen28 halamanQuality Assurance in BacteriologyAuguz Francis Acena50% (2)

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NDokumen4 halamanCompetition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NMuhammad TuriBelum ada peringkat

- Eligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Dokumen33 halamanEligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Dr. Vishal SengarBelum ada peringkat

- The Historical Development of Guidance and Counseling: September 2020Dokumen17 halamanThe Historical Development of Guidance and Counseling: September 2020Martin Kit Juinio GuzmanBelum ada peringkat

- Think Global Manila ProgramDokumen16 halamanThink Global Manila ProgramRenzo R. GuintoBelum ada peringkat

- Practical ResearchDokumen3 halamanPractical ResearchMarcos Palaca Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- Notification AAI Manager Junior ExecutiveDokumen8 halamanNotification AAI Manager Junior ExecutivesreenuBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Research Track 230221Dokumen24 halamanIntroduction To Research Track 230221Bilramzy FakhrianBelum ada peringkat

- Eng99 LiteracyRuins PDFDokumen4 halamanEng99 LiteracyRuins PDFValeria FurduiBelum ada peringkat

- WendyDokumen5 halamanWendyNiranjan NotaniBelum ada peringkat