Self-Help Alexander: by Robert Rickover

Diunggah oleh

Johnny RiverwalkJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Self-Help Alexander: by Robert Rickover

Diunggah oleh

Johnny RiverwalkHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Self-Help Alexander

by Robert Rickover

Imagine for a moment that you have a friend living on a distant

island who can never hope to study with an Alexander teacher in

person. Your friend is impressed with the many beneficial results

you've obtained from studying and applying the technique and

wants to know how he or she too can benefit from Alexander's

discoveries. What would you tell your friend? We know that

Alexander received many written requests for help, and that he took

them very seriously. I recently met a lady, who grew up in the north

of England during the 1930's and 40's who told me of her father's

correspondence with Alexander. The two men exchanged letters on

a regular basis over a period of many years.. Her father had been

interested in putting into practice the ideas he had read about in

Alexander's books and Alexander spent a considerable amount of

time and effort to help him in this project, even though the two men

never met. Alexander was very clear in his published writings that a

serious student of his work could accomplish a good deal without

the assistance of a teacher. "Anyone who will follow me through the

experiences I have set down, especially with regard to 'non-doing',

cannot fail to benefit" he wrote in the 1945 preface to the new

edition of Use of the Self. It is now nearly half a century later and

we've learned a lot more about the process of teaching the

technique. We also have new tools, like portable audio and video

equipment and the internet, that were not available in Alexander's

time. Yet very little has been done to encourage and empower the

beginning student prepared to work on his own, or with only

occasional hands-on help. What follows is a first draft of the advice I

have for such a person to help him or her started. It is intended as a

discussion piece and I welcome any comments and suggestions. I

also welcome feedback from any isolated somebody willing to

experiment... Start by reading Use of the Self, Alexander's third

book, particularly Chapter 1, "Evolution of a Technique". As with all

of Alexander's writings, these pages must be read carefully and with

a great deal of thought. Begin observing yourself in a mirror. A full

length one is best. Pay special attention to the relationship of your

whole head (not just your face) to the rest of your body. Notice how

this relationship changes as you perform simple activities like

talking, walking or raising an arm or leg. How does what you see in

the mirror correspond to what you think you're doing, and what do

you feel you're doing? Which do you think is more accurate? Take

plenty of time to explore and compare your experiences with

Alexander's. Experiment with changing the relationship of your head

to your body, perhaps tilting it a little forward or backward from the

top of your neck and observe what difference these shifts make to

your movements and to your breathing. Alexander found that the

most useful change he could make was to mentally direct his neck

to be free so that his head, followed by his body, could release in an

upward direction - delicately, without any stiffening or undue effort.

Try this. What do you notice? Does anything look or feel different?

Now, try doing the opposite. Stiffen your neck a little as you gently

push your head down towards the rest of your body. What effect

does this have on your ability to breathe, speak and perform simple

activities? What happens when you just leave yourself alone? Is

there a relationship between your head and your body that you tend

automatically to go back to? 'Exaggerate yourself' for just a

moment. Notice what happens to your head/body relationship when

you do this. Feel free to experiment in other ways that occur to you.

Pay close attention to the results of your experiments. Remember

that you are both the experimenter and the object of the

experiments. So you are always going to have to be careful that you

are not deceiving yourself. Continue comparing what you see with

what you're thinking about and what you feel. After you've

experimented in front of the mirror long enough to have made for

yourself some of the same kinds of observations that Alexander

wrote about, extend your self-study to your daily round of activities.

Can you sense how your body reacts to stressful situations, for

example? How about pleasant experiences? Does the presence of

some people act as a stimulus to tighten your neck? Do others seem

to encourage freedom and expansion in your body? Notice the

effects of sound on your physical mechanism. Experiment with

scanning your auditory 'horizon' and noting the effects of actively

listening to the highest pitched sounds available to you. These could

be high musical notes, the chirping of birds, even the sound of wind

blowing through the branches of a tree. Then, shift your conscious

attention to the lowest-pitched sounds you can hear - drum beats,

the sounds of heavy machinery, for example. What effect does this

shift have on the way you're using your body? Keep in mind that

Alexander's purpose in performing his investigations was to improve

the quality of his performance. So begin to observe other people-and animals and small children--with a view toward becoming a

good judge of quality of movement. Keep a look out for particularly

good examples of ease, balance and co-ordination. Look also for

particularly bad examples. Can you make any generalizations about

quality of movement and the nature of the head/body relationship?

Remember that Alexander spent a long time observing himself in a

mirror before he made his important discoveries. Don't expect

overnight miracles. Alfred Redden Alexander, FM's younger brother

and a brilliant teacher in his own right, gave this wonderful piece of

advice to anyone using Alexander's discoveries as a tool for selfexploration:

"Be patient, stick to principle,and it will all open up like a giant

cauliflower."

RESOURCES

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Complete Guide To The Alexander Technique - Books of Special Interest To MusiciansDokumen3 halamanThe Complete Guide To The Alexander Technique - Books of Special Interest To MusiciansElina GeorgievaBelum ada peringkat

- Mastering The Art of Singing: Bohemian Vocal StudioDokumen23 halamanMastering The Art of Singing: Bohemian Vocal StudioBlack Light Sound FJGL100% (1)

- Appendix B - Distance Tables - Metric Units PDFDokumen15 halamanAppendix B - Distance Tables - Metric Units PDFitisIBelum ada peringkat

- Breathing: The Inner Side of SingingDokumen5 halamanBreathing: The Inner Side of SingingsergioandersctBelum ada peringkat

- BreathingDokumen24 halamanBreathingKristin100% (1)

- Alexander Technique Treatise in RelationDokumen11 halamanAlexander Technique Treatise in RelationConall O'NeillBelum ada peringkat

- Healthy Voice: by Dan VascDokumen22 halamanHealthy Voice: by Dan VascscoutjohnyBelum ada peringkat

- Improve Your Breathing With The Alexander TechniqueDokumen3 halamanImprove Your Breathing With The Alexander TechniqueLeland Vall86% (14)

- The Alexander Technique - Sarah BarkerDokumen125 halamanThe Alexander Technique - Sarah BarkerArcadius 08100% (45)

- Musician, Heal Thyself!: Free Your Shoulder Region through Body MappingDari EverandMusician, Heal Thyself!: Free Your Shoulder Region through Body MappingBelum ada peringkat

- Green Field Allen The Roots of Modern MagickDokumen276 halamanGreen Field Allen The Roots of Modern Magickkhemxnum92% (12)

- Ana's Song SilverchairDokumen8 halamanAna's Song SilverchairJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Atmos Pipeline System Map 2006Dokumen1 halamanAtmos Pipeline System Map 2006Johnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Ana's Song SilverchairDokumen8 halamanAna's Song SilverchairJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Multi-Wing Engineering GuideDokumen7 halamanMulti-Wing Engineering Guidea_salehiBelum ada peringkat

- The Alexander TechniqueDokumen27 halamanThe Alexander Techniquedaniyal.az100% (1)

- Pitch, Abduction Quotient, and BreathingDokumen6 halamanPitch, Abduction Quotient, and BreathingDeyse SchultzBelum ada peringkat

- Determine Your Voice TypeDokumen7 halamanDetermine Your Voice Typeterrance moyoBelum ada peringkat

- Deep Breathing ExerciseDokumen9 halamanDeep Breathing ExerciseMohamad Nizam ErhamzaBelum ada peringkat

- Alexander Technique: Cruz, Justine Joy Escalona, Lorise Marie Yao, Jestin Robert GDokumen27 halamanAlexander Technique: Cruz, Justine Joy Escalona, Lorise Marie Yao, Jestin Robert Gjustine cruzBelum ada peringkat

- Making Yourself HeardDokumen8 halamanMaking Yourself HeardMirzo31Belum ada peringkat

- The e Ects of A Feldenkrais1 Awareness Through Movement Program On State AnxietyDokumen5 halamanThe e Ects of A Feldenkrais1 Awareness Through Movement Program On State AnxietyKaos CalmoBelum ada peringkat

- The Feldenkrais Method & MusiciansDokumen8 halamanThe Feldenkrais Method & MusiciansSilvia MuléBelum ada peringkat

- The Significance of Choral SingingDokumen18 halamanThe Significance of Choral SingingprisconetrunnerBelum ada peringkat

- Climbing The Pleasure ScaleDokumen4 halamanClimbing The Pleasure ScaleLeland Vall100% (1)

- Singing and Vocal DevelopmentDokumen26 halamanSinging and Vocal DevelopmentDESSYBEL MEDIABelum ada peringkat

- Alexander Technique and Feldenkrais MethodDokumen2 halamanAlexander Technique and Feldenkrais MethodAlfonso Aguirre DergalBelum ada peringkat

- What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body (Revised Edition): The Practical Application of Body Mapping to Making MusicDari EverandWhat Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body (Revised Edition): The Practical Application of Body Mapping to Making MusicBelum ada peringkat

- Breathing Made Simple E-BookDokumen17 halamanBreathing Made Simple E-BookErin100% (1)

- How To Sing High Notes Without Straining Your VoiceDokumen3 halamanHow To Sing High Notes Without Straining Your VoiceamazenokutendamBelum ada peringkat

- Feldenkrais para La Voz 3Dokumen30 halamanFeldenkrais para La Voz 3Valeria Sonzogni67% (3)

- Voice Improving: 1 ..How To Sing in KeyDokumen18 halamanVoice Improving: 1 ..How To Sing in KeyHassun CheemaBelum ada peringkat

- Voice Production in Singing and Speaking, Based On Scientific PrinciplesDokumen344 halamanVoice Production in Singing and Speaking, Based On Scientific PrinciplesHer BertoBelum ada peringkat

- Alexander Technique For Personal TrainersDokumen3 halamanAlexander Technique For Personal TrainersLeland Vall100% (3)

- Sing Better Than Ever (Improve Your Present Singing Voice)Dokumen14 halamanSing Better Than Ever (Improve Your Present Singing Voice)Empty MindedBelum ada peringkat

- Voiceworks: U Us Se Er R''S S M Ma An Nu Ua Al LDokumen31 halamanVoiceworks: U Us Se Er R''S S M Ma An Nu Ua Al LBratislav-Bata IlicBelum ada peringkat

- The Value of Vocal Warm-Up and Cool-Down Exercises: Questions and ControversiesDokumen3 halamanThe Value of Vocal Warm-Up and Cool-Down Exercises: Questions and ControversiesTayssa MarquesBelum ada peringkat

- Your Voice Article by Tim NoonanDokumen14 halamanYour Voice Article by Tim NoonanKhaled SamirBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan 3 Student TeachingDokumen3 halamanLesson Plan 3 Student Teachingapi-393150167Belum ada peringkat

- Moshé FeldenkraisDokumen6 halamanMoshé FeldenkraisStephan Wozniak100% (3)

- Feldenkrais Method Empowers Adults With Chronic.4Dokumen13 halamanFeldenkrais Method Empowers Adults With Chronic.4Yvette M Reyes100% (1)

- The Singing Pedagogue 2Dokumen6 halamanThe Singing Pedagogue 2thuythaoBelum ada peringkat

- Singing and Social PhobiaDokumen35 halamanSinging and Social PhobiaJohn Paul SharpBelum ada peringkat

- Voice and The Alexander TechniqueDokumen5 halamanVoice and The Alexander Techniquempcantavoz100% (2)

- The Neuropsychological Connection Between Creativity and MeditationDokumen25 halamanThe Neuropsychological Connection Between Creativity and MeditationSu AjaBelum ada peringkat

- Feel The Blearn 6-16-2016 RevisionDokumen8 halamanFeel The Blearn 6-16-2016 RevisionAlex RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

- The Feldenkrais Journal 17 General IssueDokumen76 halamanThe Feldenkrais Journal 17 General IssuePHILIPPE100% (1)

- Alexander Technique and ActingDokumen33 halamanAlexander Technique and ActingatsteBelum ada peringkat

- Feldenkrais®: & The BrainDokumen9 halamanFeldenkrais®: & The BrainPhytodoc0% (1)

- NO SINGING Voice Lesson 1 PDFDokumen5 halamanNO SINGING Voice Lesson 1 PDFCecelia ChoirBelum ada peringkat

- Music and The Young Child-Finished ProductDokumen3 halamanMusic and The Young Child-Finished ProductSaiful Hairin RahmatBelum ada peringkat

- U200: Academic Writing: Effective SpeakingDokumen12 halamanU200: Academic Writing: Effective SpeakingBart T Sata'oBelum ada peringkat

- Chiaroscuro Whisper Vowel ModelingDokumen2 halamanChiaroscuro Whisper Vowel ModelingNathan WiseBelum ada peringkat

- Breathing & Warm-Up TipsDokumen10 halamanBreathing & Warm-Up TipsJordan KerrBelum ada peringkat

- Impulstanz Workshop Schedule 2009Dokumen116 halamanImpulstanz Workshop Schedule 2009Martin FrenchBelum ada peringkat

- Build Your Own WarmupDokumen8 halamanBuild Your Own WarmupBaia AramaraBelum ada peringkat

- How to Sing Your Own Song of Success: And Transform Your LifeDari EverandHow to Sing Your Own Song of Success: And Transform Your LifeBelum ada peringkat

- The Boy's Voice A Book of Practical Information on The Training of Boys' Voices For Church Choirs, &c.Dari EverandThe Boy's Voice A Book of Practical Information on The Training of Boys' Voices For Church Choirs, &c.Belum ada peringkat

- The Power of Sound: Exploring the Link between Sound Waves and Positive ThoughtDari EverandThe Power of Sound: Exploring the Link between Sound Waves and Positive ThoughtBelum ada peringkat

- Fairy Mythology of ShakespeareDokumen18 halamanFairy Mythology of ShakespeareJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- The Roots of Modern MagickDokumen276 halamanThe Roots of Modern MagickJohnny Riverwalk50% (2)

- English Bluray ManualDokumen72 halamanEnglish Bluray ManualJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Documents StackDokumen1 halamanDocuments StackDan MBelum ada peringkat

- The Mathematics of HarmonyDokumen19 halamanThe Mathematics of HarmonyJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Characters Three Sisters (Antoine Chejov) : The ProzorovsDokumen5 halamanCharacters Three Sisters (Antoine Chejov) : The ProzorovsJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- WikipuckDokumen11 halamanWikipuckJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Exhibit 11x17 - Dilley - Site - PlanDokumen1 halamanExhibit 11x17 - Dilley - Site - PlanJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Bio CompanyDokumen4 halamanBio CompanyJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation e CigarettesDokumen8 halamanEvaluation e Cigarettessesisan200950% (2)

- OPH Keller CASAA-2012-Dissolvables TPSAC ReportDokumen11 halamanOPH Keller CASAA-2012-Dissolvables TPSAC ReportJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- AnuarioDokumen11 halamanAnuarioJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- How Do I Use Advanced Search?: Clicking HereDokumen2 halamanHow Do I Use Advanced Search?: Clicking HereJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Anadarko BasinDokumen2 halamanAnadarko BasinJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- 12 State PlanDokumen286 halaman12 State PlanJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- The Changing Face of The Oil and Gas Industry in CanadaDokumen45 halamanThe Changing Face of The Oil and Gas Industry in CanadaJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Continental Resources Investor Day 2012Dokumen136 halamanContinental Resources Investor Day 2012Johnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Rod StewartDokumen4 halamanRod StewartJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Continental Resources Investor Day 2012Dokumen136 halamanContinental Resources Investor Day 2012Johnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Eagle Ford Shale CompaniesDokumen14 halamanEagle Ford Shale CompaniesJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- An Example CVDokumen1 halamanAn Example CVJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation e CigarettesDokumen8 halamanEvaluation e Cigarettessesisan200950% (2)

- How Do I Use Advanced Search?: Clicking HereDokumen2 halamanHow Do I Use Advanced Search?: Clicking HereJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- Ccna4 ExamDokumen16 halamanCcna4 ExamJohnny RiverwalkBelum ada peringkat

- The Emom Manual: 25 Kettlebell Conditioning WorkoutsDokumen14 halamanThe Emom Manual: 25 Kettlebell Conditioning WorkoutsguilleBelum ada peringkat

- List of 100 New English Words and MeaningsDokumen5 halamanList of 100 New English Words and MeaningsNenad AngelovskiBelum ada peringkat

- Libro Resumenes 2012Dokumen735 halamanLibro Resumenes 2012fdobonat613100% (2)

- Adenoid HypertrophyDokumen56 halamanAdenoid HypertrophyWidi Yuli HariantoBelum ada peringkat

- Turning Risk Into ResultsDokumen14 halamanTurning Risk Into Resultsririschristin_171952Belum ada peringkat

- PMI Framework Processes PresentationDokumen17 halamanPMI Framework Processes PresentationAakash BhatiaBelum ada peringkat

- Pantera 900Dokumen3 halamanPantera 900Tuan Pham AnhBelum ada peringkat

- Outlook 2Dokumen188 halamanOutlook 2Mafer Garces NeuhausBelum ada peringkat

- Notes Marriage and Family in Canon LawDokumen5 halamanNotes Marriage and Family in Canon LawmacBelum ada peringkat

- OPSS1213 Mar98Dokumen3 halamanOPSS1213 Mar98Tony ParkBelum ada peringkat

- Laboratory Cold ChainDokumen22 halamanLaboratory Cold ChainEmiBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Employee Motivation in The Banking SectorDokumen48 halamanImpact of Employee Motivation in The Banking Sectormohd talalBelum ada peringkat

- Gender, Slum Poverty and Climate Change in Flooded River Lines in Metro ManilaDokumen53 halamanGender, Slum Poverty and Climate Change in Flooded River Lines in Metro ManilaADBGADBelum ada peringkat

- Intro To Psychological AssessmentDokumen7 halamanIntro To Psychological AssessmentKian La100% (1)

- WWW Spectrosci Com Product Infracal Model CVH PrinterFriendlDokumen3 halamanWWW Spectrosci Com Product Infracal Model CVH PrinterFriendlather1985Belum ada peringkat

- GrowNote Faba South 3 Pre PlantingDokumen22 halamanGrowNote Faba South 3 Pre PlantingDawitBelum ada peringkat

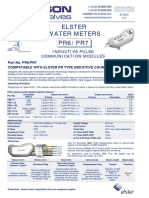

- Data Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleDokumen1 halamanData Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleThaynar BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Flame Retardant and Fire Resistant Cable - NexansDokumen2 halamanFlame Retardant and Fire Resistant Cable - NexansprseBelum ada peringkat

- Village Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Dokumen4 halamanVillage Survey Form For Project Gaon-Setu (Village Questionnaire)Yash Kotadiya100% (2)

- 2133 Rla RlvaDokumen2 halaman2133 Rla RlvaAgung SubangunBelum ada peringkat

- QA-QC TPL of Ecube LabDokumen1 halamanQA-QC TPL of Ecube LabManash Protim GogoiBelum ada peringkat

- Advances of Family Apocynaceae A Review - 2017Dokumen30 halamanAdvances of Family Apocynaceae A Review - 2017Владимир ДружининBelum ada peringkat

- Pioneer PDP 5071 5070pu Arp 3354Dokumen219 halamanPioneer PDP 5071 5070pu Arp 3354Dan Prewitt100% (1)

- Engineering Project ListDokumen25 halamanEngineering Project ListSyed ShaBelum ada peringkat

- 1A Wound Care AdviceDokumen2 halaman1A Wound Care AdviceGrace ValenciaBelum ada peringkat

- Narrative Report On Weekly Accomplishments: Department of EducationDokumen2 halamanNarrative Report On Weekly Accomplishments: Department of Educationisha mariano100% (1)

- Updoc - Tips Dictionar Foraj e RDokumen37 halamanUpdoc - Tips Dictionar Foraj e RDaniela Dandea100% (1)

- Funding HR2 Coalition LetterDokumen3 halamanFunding HR2 Coalition LetterFox NewsBelum ada peringkat