Severe Cholestasis and Renal Failure Associated With The Use of The Designer Steroid Superdrol™ (Methasteron™) A Case Report and Literature Review

Diunggah oleh

Pádraig Ó ĊonġaileJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Severe Cholestasis and Renal Failure Associated With The Use of The Designer Steroid Superdrol™ (Methasteron™) A Case Report and Literature Review

Diunggah oleh

Pádraig Ó ĊonġaileHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Dig Dis Sci (2009) 54:11441146

DOI 10.1007/s10620-008-0457-x

CASE REPORT

Severe Cholestasis and Renal Failure Associated with the Use of

the Designer Steroid SuperdrolTM (MethasteronTM): A Case Report

and Literature Review

John Nasr Jawad Ahmad

Received: 28 November 2007 / Accepted: 16 July 2008 / Published online: 22 August 2008

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008

Abbreviations

AAS Androgenic/anabolic steroids

OTC Over the counter

Introduction

The use of over the counter (OTC) nutritional supplements

is widespread among amateur bodybuilders. Reports suggest that up to 30% of people who train regularly with

weights use androgenic/anabolic steroids (AAS) and that a

significant percentage of male high school students use

AAS, not just for muscle gain but also to improve their

physical appearance [1, 2]. The use of AAS is associated

with a variety of potential liver injuries including toxic

hepatitis and cholestasis [3, 4] but is often under-reported

because of its clandestine use. Renal toxicity with the use

of AAS has recently been demonstrated, which was

thought to be related to IgA nephropathy [5]. We report a

case of liver and renal injury secondary to a nutritional

supplement called SuperdrolTM, with the anabolic steroidmethasteronTM as its active ingredient.

Case Report

A 42-year-old Caucasian male with no known past medical

history presented with a 4-week history of jaundice, diffuse

J. Nasr

Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh,

Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

J. Ahmad (&)

Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition,

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

e-mail: ahmadj@msx.upmc.edu

123

pruritus, and dark urine with a 20-pound weight loss.

Approximately 7 weeks prior to the onset of his symptoms,

the patient had started using a nutritional supplement for

bodybuilders called SuperdrolTM. He consumed 100 tablets

of SuperdrolTM, taking two tablets each day. He did not

exceed the maximal suggested dose of 126 tablets. Four

days after he stopped the SuperdrolTM, the patient noticed

scleral icterus and jaundice. Three days later, he started

experiencing diffuse pruritus. There was no history of

alcohol, recreational drugs, or tobacco use, and no family

history of liver or kidney disease. There was no prior history

of nutritional supplement use prior to this course of SuperdrolTM although he was taking multivitamin and protein

milkshakes. He was not taking any prescription medication.

Upon physical examination, his vital signs were stable.

He had scleral icterus and jaundice but no other stigmata of

chronic liver disease. His cardiovascular and respiratory

systems were normal. His abdominal examination demonstrated a soft, non-tender abdomen without evidence of

ascites or hepatosplenomegaly.

At presentation, laboratory parameters revealed a total

bilirubin of 41.2 mg/dl (normal 0.31.5), an AST of

63 IU/l (normal 1040), ALT of 98 IU/l (normal 1040),

alkaline phosphatase of 353 IU/l (normal 40125), and

total protein of 8.1 g/dl (normal 6.37.7). Serology for

viral hepatitis was essentially negative including hepatitis

A-IgM antibody, hepatitis B core-IgM antibody, hepatitis

B surface antigen, hepatitis B core-IgG antibody, hepatitis C antibody, as well as hepatitis C RNA, and hepatitis

B DNA by polymerase chain reaction. His hepatitis B

surface antibody was positive at a high titer from prior

vaccination. Hemoglobin, white cell count, and platelets

were normal. Serum ceruloplasmin and serum alpha-1

antitrypsin levels, smooth muscle, antinuclear, and antiLKM antibodies were normal. Electrolytes were normal

Dig Dis Sci (2009) 54:11441146

Fig. 2 Liver biopsy showing panlobular hepatocanalicular cholestasis with formation of inspissated canalicular bile plugs (arrows ).

(Hematoxylin and Eosin, 9400)

45

40

Total bilirubin (mg/dl)

but his creatinine was elevated at 3.6 mg/dl (normal 0.5

1.4) and his BUN was 43 mg/dl (normal 520). Urinalysis showed bland urine sediment without red cells or

casts and a 24-hour urine collection was significant for

1,005 mg protein (normal 42225). Ultrasound demonstrated no renal obstruction with bilateral echogenic

kidneys. MRI showed a normal liver and biliary tree. A

presumptive diagnosis of drug-induced liver and kidney

injury was made. The patient was admitted for 4 days

and discharged on oral ursodeoxycholic acid at 600 mg

twice daily and hydroxyzine 25 mg as required for pruritus. Upon discharge, the patient had a bilirubin of

42.1 mg/dl and creatinine of 4.2 mg/dl.

The patient was readmitted a second time a week later

for intractable pruritus and was discharged on naltrexone.

At that time, his creatinine had fallen to 2.3 mg/dl and

bilirubin 34.3 g/dl. After a month, the patient remained

jaundiced with minimal improvement in his bilirubin

and cholestatic liver enzymes but his renal function had

essentially normalized. A liver biopsy was performed

demonstrating hepatocyte regeneration and lobular activity with marked hepatocanalicular cholestasis, bile

ductular reaction with neutrophilic cholangiolitis and

focal early bridging fibrosis suggestive of a drug-induced

cholestatic injury (Figs. 1, 2). Two weeks later, the

patients pruritus had significantly improved with normalization of his kidney function and bilirubin had

improved to 8 mg/dl with a normal alkaline phosphatase.

There was continued gradual improvement and 4 months

after his initial presentation his bilirubin normalized.

Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate the trends in his bilirubin

and creatinine.

1145

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

0

10

14

21

28

42

49

63

77

91

112

Days after initial presentation

Fig. 3 Graph demonstrating trend in total bilirubin over time

Serum creatinine (mg/dl)

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

10

14

21

28

42

49

77

Days after initial presentation

Fig. 4 Graph demonstrating trend in serum creatinine over time

Discussion

Fig. 1 Liver biopsy showing irregular fibrous expansion of portal

tracts with mild inflammatory infiltrate and bile ductular reaction. The

inflammatory infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes and some

neutrophils (Hematoxylin and Eosin, 9200)

Self-administration of AAS to increase muscular strength

and lean body mass is a widespread practice, even though

the indiscriminate use of such drugs may constitute a serious health risk [6]. AAS are synthetic derivatives of

123

1146

testosterone that can be chemically altered to enhance either

anabolic or androgenic effects. When used in therapeutic

doses they have been used to treat testicular failure, wasting

syndromes, victims of severe burns, and some hematological conditions such as aplastic anemia [79]. However,

when used for athletic performance, the doses used can be

far in excess of normal physiologic levels and this presumably explains the increase in toxic effects [10]. The

hepatotoxicity of AAS typically manifests as cholestasis but

predominant hepatocellular injury, peliosis hepatis and

hepatic adenomas have also been reported [3, 7, 1113].

The liver biopsy in the current case was characteristic of the

usual type of injury seen with AAS with mild lobular

inflammation but marked canalicular cholestasis. The

mechanism of liver injury is unclear but recovery after

cessation of therapy almost always occurs [14].

The patient was started on ursodeoxycholic acid empirically because of the degree of cholestasis and we doubt

whether this accelerated the improvement in his bilirubin.

The rapid drop in bilirubin after day 28 may reflect the

improvement in renal function and hence enhanced bilirubin

excretion. The 1012 weeks that elapsed for normalization

of his bilirubin is consistent with other reports of the length of

time necessary for spontaneous resolution of AAS associated

liver injury.

Renal toxicity with AAS has only been reported once

previously [5] and was associated with changes of IgA

nephropathy on kidney biopsy. We did not biopsy our

patient as his renal function improved spontaneously in 10

14 days after his initial presentation, and the urine sediment did not reveal hematuria. Presumably, the cause of

renal dysfunction was drug-related.

SuperdrolTM is an over the counter (OTC) nutritional

supplement that is available freely over the Internet from a

variety of different distributors. Its active ingredient is methasteronTM (2a-17a0dimethyl-5a-androst-3-one), which is

advertised as definitely not a prohormone: it is a very active

form of a designer supplement that is also highly anabolic.

[15]. Most suppliers mention minimal side effects, and give

testimonials from users that describe muscle gain and very few

side-effects. The standard Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) label for supplements is used on Internet sites: The

products and the claims made about specific products on or

through this site have not been evaluated by the FDA. They are

not approved to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent disease. The

information provided on this site is for informational purposes

only and is not intended as a substitute for advice from your

physician or other health care professional or any information

contained on or in any product label or packaging. Despite

this warning, AAS continue to be used by amateur weight

trainers and particularly adolescents [1, 2]. This case highlights the potential hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity of these

agents but numerous other effects including psychological

123

Dig Dis Sci (2009) 54:11441146

changes, decreased sperm count, and adverse lipid profiles

have been seen [16]. The lack of federal regulation of OTC

nutritional supplements means that physicians need to be

vigilant in suspecting the use of AAS, particularly in young

male patients presenting with unexplained elevated liver

injury tests and even renal dysfunction.

References

1. Parkinson AB, Evans NA. Anabolic androgenic steroids: a survey

of 500 users. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:644651. doi:

10.1249/01.mss.0000210194.56834.5d.

2. Handelsman DJ, Gupta L. Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse in Australian high school students.

Int J Androl. 1997;20:159164. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1997.

d01-285.x.

3. Stimac D, Milic S, Dintinjana RD, Kovac D, Ristic S. Androgenic/

anabolic steroid-induced toxic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol.

2002;35:350352. doi:10.1097/00004836-200210000-00013.

4. Hartgens F, Kuipers H. Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in

athletes. Sports Med. 2004;34:513554. doi:10.2165/00007256200434080-00003.

5. Jasiurkowski B, Raj J, Wisinger D, Carlson R, Zou L, Nadir A.

Cholestatic jaundice and IgA nephropathy induced by OTC

muscle building agent superdrol. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:

26592662.

6. Maravelias C, Dona A, Stefanidou M, et al. Adverse effects of

anabolic steroids in athletes. A constant threat. Toxicol Lett.

2005;158:167175. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.06.005.

7. Sanchez-Osorio M, Duarte-Rojo A, Martinez-Benitez B, Torre A,

Uribe M. Anabolic-androgenic steroids and liver injury. Liver Int.

2007; Epub ahead of print.

8. Orr R, Fiatorone Singh M. The anabolic androgenic steroid

oxandrolone in the treatment of wasting and catabolic disorders:

review of efficacy and safety. Drugs. 2004;64:725750. doi:

10.2165/00003495-200464070-00004.

9. Murphy KD, Thomas S, Mlcak RP, Chinkes DL, Klein GL,

Herndon DN. Effects of long-term oxandrolone administration in

severely burned children. Surgery. 2004;136:219224. doi:

10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.022.

10. Hall RC, Hall RC. Abuse of supraphysiologic doses of anabolic

steroids. South Med J. 2005;98:550555. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.

0000157531.04472.B2.

11. Bagheri SA, Boyer JL. Peliosis hepatis associated with androgenic-anabolic steroid therapy. A severe form of hepatic injury.

Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:610618.

12. Socas L, Zumbado M, Perez-Luzardo O, Ramos A, Perez C,

Hernandez JR. Hepatocellular adenomas associated with anabolic

androgenic steroid abuse in bodybuilders: a report of two cases

and a review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:e27. doi:

10.1136/bjsm.2004.013599.

13. Carrasco D, Prieto M, Pallardo L, et al. Multiple hepatic adenomas

after long-term therapy with testosterone enanthate. Review of the

literature. J Hepatol. 1985;1:573578. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278

(85)80001-5.

14. Gurakar A, Caraceni P, Fagiuoli S, Van Thiel DH. Androgenic/

anabolic steroid-induced cholestasis: a review with four additional case reports. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1994;87:399404.

15. http://www.worldclassnutrition.com/superdrol.html.

16. Bonetti A, Tirelli F, Catapano A, Dazzi D, Dei Cas A, Solito F,

et al. Side effects of anabolic androgenic steroids abuse. Int J

Sports Med. 2007; Epub ahead of print.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Case 13 Case StudyDokumen8 halamanCase 13 Case Studyklee100% (2)

- MKSAP18 Rheumatology PDFDokumen169 halamanMKSAP18 Rheumatology PDFHoang pham33% (3)

- Case 13 Medical Nutrition TherapyDokumen8 halamanCase 13 Medical Nutrition TherapykleeBelum ada peringkat

- Pre-NEET Surgery (Khandelwal & Arora) PDFDokumen124 halamanPre-NEET Surgery (Khandelwal & Arora) PDFdrng4850% (4)

- Course in The WardDokumen12 halamanCourse in The WardBunzay GelineBelum ada peringkat

- OphthalmologyDokumen29 halamanOphthalmologyAdebisiBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Test Questions For The CPC Exam-2Dokumen6 halamanSample Test Questions For The CPC Exam-2Anonymous MtKJkerbpUBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Care Plan For "Lymphomas"Dokumen9 halamanNursing Care Plan For "Lymphomas"jhonroks89% (9)

- Hepatotoxicity Induced by High Dose of Methylprednisolone Therapy in A Patient With Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Brief Review of LiteratureDokumen5 halamanHepatotoxicity Induced by High Dose of Methylprednisolone Therapy in A Patient With Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Brief Review of LiteratureBayu ParmikaBelum ada peringkat

- 2014 Article 109Dokumen4 halaman2014 Article 109luckytacandraBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Pancreatitis With Normal Serum Lipase: A Case SeriesDokumen4 halamanAcute Pancreatitis With Normal Serum Lipase: A Case SeriesSilvina VernaBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies For Alcoholic Liver Disease: A Retrospective Real-World Evidence StudyDokumen13 halamanEvaluation of Pharmacotherapies For Alcoholic Liver Disease: A Retrospective Real-World Evidence StudyEditor ERWEJBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Kidney Injury Due To Pien Tze HuangDokumen3 halamanAcute Kidney Injury Due To Pien Tze HuangDavid PalashBelum ada peringkat

- Dialysis Free Protocol For Some End Stage Renal Disease PatientsDokumen7 halamanDialysis Free Protocol For Some End Stage Renal Disease PatientsDannieCiambelliBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Conivaptan To Allow Aggressive Hydration To Prevent Tumor Lysis Syndrome in A Pediatric Patient With Large-Cell Lymphoma and SIADHDokumen5 halamanUse of Conivaptan To Allow Aggressive Hydration To Prevent Tumor Lysis Syndrome in A Pediatric Patient With Large-Cell Lymphoma and SIADHmaryBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Pancreatitis PathoDokumen5 halamanAcute Pancreatitis PathoEBelum ada peringkat

- DILIDokumen28 halamanDILIsepti nurhidayatiBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Course and Diagnosis of Drug Induced LiveDokumen6 halamanClinical Course and Diagnosis of Drug Induced LiveArryo P SudharyanaBelum ada peringkat

- Test Pattern and Prognosis Liver Function Abnormalities During Parenteral Nutrition in Inflammatory DiseaseDokumen6 halamanTest Pattern and Prognosis Liver Function Abnormalities During Parenteral Nutrition in Inflammatory DiseaseAsri RachmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Primary Care Approach To Proteinuria: Amir Said Alizadeh Naderi, MD, and Robert F. Reilly, MDDokumen6 halamanPrimary Care Approach To Proteinuria: Amir Said Alizadeh Naderi, MD, and Robert F. Reilly, MDraviibtBelum ada peringkat

- 12 CR Methotrexate Induced LiverDokumen2 halaman12 CR Methotrexate Induced LiverAnonymous bFByZ3FydBelum ada peringkat

- Do Proton Pump Inhibitors Increase Mortality in Cirrhotic Patients With Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis?Dokumen29 halamanDo Proton Pump Inhibitors Increase Mortality in Cirrhotic Patients With Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis?Muhammad Rehan AnisBelum ada peringkat

- Abnormal Liver Function TestsDokumen6 halamanAbnormal Liver Function Testskronic12daniBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report: Acute Liver Injury With Severe Coagulopathy in Marasmus Caused by A Somatic Delusional DisorderDokumen3 halamanCase Report: Acute Liver Injury With Severe Coagulopathy in Marasmus Caused by A Somatic Delusional DisorderNur Ismi Mustika FebrianiBelum ada peringkat

- Antidepresive + Insuf. Hep.Dokumen13 halamanAntidepresive + Insuf. Hep.Robert MovileanuBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction of CKDDokumen7 halamanIntroduction of CKDAndrelyn Balangui LumingisBelum ada peringkat

- HerbalifeDokumen7 halamanHerbalifeLuis Galeana MuñozBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Small Animals1Dokumen16 halamanChronic Kidney Disease in Small Animals1ZiedTrikiBelum ada peringkat

- 1.1. Adv. Biopharma.-A-Dose Adjustment in Renal & Hepatic Failure - by M.firoz KhanDokumen38 halaman1.1. Adv. Biopharma.-A-Dose Adjustment in Renal & Hepatic Failure - by M.firoz KhanRaju NiraulaBelum ada peringkat

- How Rob Reversed His Chronic Kidney Disease in Just Two MonthsDokumen4 halamanHow Rob Reversed His Chronic Kidney Disease in Just Two Monthsmamunur rashidBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Renal FailureDokumen5 halamanAcute Renal FailureJean De Vera MelendezBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Collection FinalDokumen11 halamanLiterature Collection FinalNatarajan NalanthBelum ada peringkat

- Normal Protein Diet and L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate For Hepatic EncephalopathyDokumen4 halamanNormal Protein Diet and L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate For Hepatic EncephalopathyElisa SalakayBelum ada peringkat

- Pi Is 0025619611601213Dokumen5 halamanPi Is 0025619611601213FarmaIndasurBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal KimiaDokumen9 halamanJurnal KimiaTeguh DesmansyahBelum ada peringkat

- Bookshelf NBK548030 PDFDokumen8 halamanBookshelf NBK548030 PDFSalud Familiar Juan Pablo IIBelum ada peringkat

- Uric Acid: Suggestions For Clinical CareDokumen5 halamanUric Acid: Suggestions For Clinical CareChandan SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Tuberculosis in Liver Cirrhosis: Rajesh Upadhyay, Aesha SinghDokumen3 halamanTuberculosis in Liver Cirrhosis: Rajesh Upadhyay, Aesha SinghAnastasia Lilian SuryajayaBelum ada peringkat

- Case ReportDokumen5 halamanCase ReportAlfi YatunBelum ada peringkat

- Letter To The Editor Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in Adults: Clinics 2008 63 (2) :273-6Dokumen4 halamanLetter To The Editor Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in Adults: Clinics 2008 63 (2) :273-6donkeyendutBelum ada peringkat

- Referat Aborsi Forensik FixDokumen63 halamanReferat Aborsi Forensik FixNUR AZIZAHBelum ada peringkat

- Qat Chewing and Autoimmune Hepatitis - True Association or CoincidenceDokumen7 halamanQat Chewing and Autoimmune Hepatitis - True Association or CoincidenceinunBelum ada peringkat

- Ibit 04 I 4 P 254Dokumen2 halamanIbit 04 I 4 P 254Kareem MontafkhBelum ada peringkat

- Clinicalmanifestationsand Treatmentofdrug-Induced HepatotoxicityDokumen9 halamanClinicalmanifestationsand Treatmentofdrug-Induced HepatotoxicityChâu Khắc ToànBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Study On Urinalysis and Body FluidsDokumen17 halamanA Case Study On Urinalysis and Body Fluidsrakish16Belum ada peringkat

- Ajuste de Dosis de Medicamentos en Paciente RenalDokumen46 halamanAjuste de Dosis de Medicamentos en Paciente RenalThelma Cantillo RochaBelum ada peringkat

- Phenelzine - Liver ToxicityDokumen8 halamanPhenelzine - Liver Toxicitydo leeBelum ada peringkat

- 632 Management of Nonalcoholic SteatohepatitisDokumen15 halaman632 Management of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitispedrogarcia7Belum ada peringkat

- Febuxostat (Uloric), A New Treatment Option For Gout: Carmela Avena-Woods Olga Hilas Author Information Go ToDokumen9 halamanFebuxostat (Uloric), A New Treatment Option For Gout: Carmela Avena-Woods Olga Hilas Author Information Go ToAnadi GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Indications For Initiation of DialysisDokumen11 halamanIndications For Initiation of DialysisMilton BenevidesBelum ada peringkat

- Materials and MethodsDokumen15 halamanMaterials and MethodsParoma ArefinBelum ada peringkat

- NSAID Colon UlcersDokumen5 halamanNSAID Colon UlcersFrederic IkkiBelum ada peringkat

- Liver Function Tests PDFDokumen11 halamanLiver Function Tests PDFVangelis NinisBelum ada peringkat

- Hepatic FailureDokumen37 halamanHepatic FailureWinston Dela FuenteBelum ada peringkat

- The Use of Albumin For The Prevention of Hepatorenal Syndrome in Patients With Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and CirrhosisDokumen14 halamanThe Use of Albumin For The Prevention of Hepatorenal Syndrome in Patients With Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and CirrhosisPaulus MetehBelum ada peringkat

- Gout Itsnotall Crystal ClearDokumen53 halamanGout Itsnotall Crystal ClearAnita MavazheBelum ada peringkat

- Paper Insulin Resistance and Ferritin As Major Determinants of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Apparently Healthy Obese PatientsDokumen7 halamanPaper Insulin Resistance and Ferritin As Major Determinants of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Apparently Healthy Obese PatientsNike Dwi Putri LestariBelum ada peringkat

- Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2000 - Rifampicin-Induced Acute Renal Failure and HepatitisDokumen2 halamanVolume 1, Issue 1, December 2000 - Rifampicin-Induced Acute Renal Failure and HepatitisWelki VernandoBelum ada peringkat

- Oftal Case StudyDokumen11 halamanOftal Case StudyMohamad RaisBelum ada peringkat

- Wang 2019Dokumen26 halamanWang 2019Omid AlizadehBelum ada peringkat

- Liver FailureDokumen10 halamanLiver FailurekennfenwBelum ada peringkat

- GOUT PresentationDokumen24 halamanGOUT Presentationtasneemsofi100% (1)

- 26 Manjula Devi - Docx CorrectedDokumen11 halaman26 Manjula Devi - Docx Correctednoviantyramadhani12Belum ada peringkat

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyDari EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (1)

- Chromatin Extraction Materials: Mostoslavsky's Lab ProtocolsDokumen2 halamanChromatin Extraction Materials: Mostoslavsky's Lab ProtocolsPádraig Ó ĊonġaileBelum ada peringkat

- Enhanced Codeine and Morphine Production in SuspendedDokumen5 halamanEnhanced Codeine and Morphine Production in SuspendedPádraig Ó ĊonġaileBelum ada peringkat

- 2,5 Dimethoxy 4 Methylamphetamine New Hallucinogenic DrugDokumen2 halaman2,5 Dimethoxy 4 Methylamphetamine New Hallucinogenic DrugPádraig Ó ĊonġaileBelum ada peringkat

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokumen15 halamanNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptPádraig Ó ĊonġaileBelum ada peringkat

- Spigelian Hernia ReadingDokumen26 halamanSpigelian Hernia Readinghimanshugupta811997Belum ada peringkat

- Obsessive - Compulsive Personality Disorder: A Current ReviewDokumen10 halamanObsessive - Compulsive Personality Disorder: A Current ReviewClaudia AranedaBelum ada peringkat

- NCMA 217 - Newborn Assessment Ma'am JhalDokumen5 halamanNCMA 217 - Newborn Assessment Ma'am JhalMariah Blez BognotBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Rare Remedies in Homoeopathic Practice: Dr. Ayush Kumar GuptaDokumen8 halamanUse of Rare Remedies in Homoeopathic Practice: Dr. Ayush Kumar GuptaIndhumathiBelum ada peringkat

- Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: How Do Current Practice Guidelines Affect Management?Dokumen8 halamanDifferentiated Thyroid Cancer: How Do Current Practice Guidelines Affect Management?wafasahilahBelum ada peringkat

- DapusDokumen1 halamanDapusJihadBelum ada peringkat

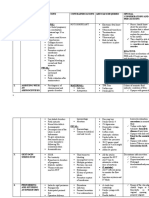

- S.NO. Name of Procedure Indications Contraindications Articles Required Special Considerations and Precautions 1. Non-Stress Test MaternalDokumen4 halamanS.NO. Name of Procedure Indications Contraindications Articles Required Special Considerations and Precautions 1. Non-Stress Test Maternaljyoti ranaBelum ada peringkat

- Management of Asthma: A Guide To The Essentials of Good Clinical PracticeDokumen100 halamanManagement of Asthma: A Guide To The Essentials of Good Clinical Practicemalvika chawlaBelum ada peringkat

- Poster Case Report Revisi 1Dokumen1 halamanPoster Case Report Revisi 1Lalu Rizky AdipuraBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Guide SHR ModuleDokumen7 halamanClinical Guide SHR ModuleNisroc MorrisonBelum ada peringkat

- Indications and Contraindications of Laparoscopy1Dokumen18 halamanIndications and Contraindications of Laparoscopy1drhiwaomer100% (2)

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus in LowerDokumen6 halamanRespiratory Syncytial Virus in LowerShailendra ParajuliBelum ada peringkat

- The Grey Matter: Something in The AirDokumen28 halamanThe Grey Matter: Something in The AirMinaz PatelBelum ada peringkat

- Executive Order No. 003-ADokumen2 halamanExecutive Order No. 003-AAndrew Murray D. DuranoBelum ada peringkat

- Alcoholism ShresthaDokumen9 halamanAlcoholism ShresthaTapas PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Gastrointestinal Imaging - The Requisites (4e) (2014) (Unitedvrg)Dokumen435 halamanGastrointestinal Imaging - The Requisites (4e) (2014) (Unitedvrg)crazyballerman80890% (10)

- Per-Pl 206Dokumen266 halamanPer-Pl 206Wan YusufBelum ada peringkat

- Viral Gastroenteritis-1Dokumen17 halamanViral Gastroenteritis-1Abdus SubhanBelum ada peringkat

- CBT For Tinnitus (20 Nov 2023)Dokumen48 halamanCBT For Tinnitus (20 Nov 2023)agietz27Belum ada peringkat

- Penatalaksanaan Keperawatan Covid 19 Di Respiratory Ward AustraliaDokumen22 halamanPenatalaksanaan Keperawatan Covid 19 Di Respiratory Ward AustraliaRadenroro Atih Utari RizkyBelum ada peringkat

- Epidemiology of Non-Communicable DiseasesDokumen57 halamanEpidemiology of Non-Communicable Diseasessarguss1492% (12)

- HPV Vaccination: It'S Us Against The Human PapillomavirusDokumen30 halamanHPV Vaccination: It'S Us Against The Human Papillomavirussalam majzoubBelum ada peringkat

- History (Awasir)Dokumen37 halamanHistory (Awasir)Yousef TaqatqehBelum ada peringkat

- Laporan GiziDokumen11 halamanLaporan GiziEfrata MadridistaBelum ada peringkat

- 155 Latest Drugs - Neet PG Next PG Ini Cet FmgeDokumen16 halaman155 Latest Drugs - Neet PG Next PG Ini Cet FmgeSamikshya NayakBelum ada peringkat