LOOMIS y FINN. Development and Validation of A Specialization

Diunggah oleh

sir3liotJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

LOOMIS y FINN. Development and Validation of A Specialization

Diunggah oleh

sir3liotHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

This article was downloaded by: [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca]

On: 25 September 2012, At: 00:20

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:

1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street,

London W1T 3JH, UK

Human Dimensions of

Wildlife: An International

Journal

Publication details, including instructions for

authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uhdw20

Development and

Validation of a

Specialization Index and

Testing of Specialization

Theory

Ronald J. Salz, David K. Loomis & Kelly L.

Finn

Version of record first published: 29 Oct 2010.

To cite this article: Ronald J. Salz, David K. Loomis & Kelly L. Finn (2001):

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index and Testing of

Specialization Theory, Human Dimensions of Wildlife: An International Journal,

6:4, 239-258

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/108712001753473939

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/

terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study

purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,

reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make

any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate

or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug

doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The

publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising

directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this

material.

Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 6:239258, 2001

Copyright 2001 Taylor & Francis

1087-1209 /01 $12.00 + .00

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization

Index and Testing of Specialization Theory

RONALD J. SALZ

DAVID K. LOOMIS

Human Dimensions Research Unit

University of Massachusetts-Amherst

Amherst, Massachusetts, USA

KELLY L. FINN

California Department of Transportation

San Diego, California, USA

Recreation specialization can be viewed as a continuum of behavior from

the general to the particular. Along this continuum, participants can be located into meaningful subgroups based on specific criteria. Previous studies have defined, measured, and segmented specialization groups in a variety of ways. The research reported here builds on the Ditton, Loomis, and

Choi reconceptualization of recreation specialization. A specialization index was developed to segment anglers into four groups based on their orientation, experiences, relationships, and commitment. Internal validation

analysis supported the use of this specialization index as a tool for angler

segmentation. Subsequent hypotheses tested for differences among specialization groups in frequency of participation, importance of activity and

nonactivity-specific elements, support for management regulations, and sidebets. Results provide strong support for the conceptual framework developed

by Ditton et al. These findings indicate a multidimensional index can be

used to segment anglers into discreet, meaningful specialization categories.

Keywords Recreation specialization, segmentation, specialization index,

anglers

Partial funding for this project was provided by the Cooperative State Research, Extension,

Education Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station

Project Number 782.

Address correspondence to David K. Loomis, Department of Natural Resources Conservation,

Human Dimensions Research Unit, Holdsworth National Resources Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003-4210. E-mail: Loomis@forwild.umass.edu

239

240

R. J. Salz et al.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Introduction

Outdoor recreation participants generally display wide variation in their experiences, avidity, expertise, commitment, economic expenditures, and social interactions related to a particular activity. Connected to this variation are important

sociological and psychological differences affecting motivations, expectations,

desired outcomes, satisfaction levels, perceptions, and social norms. Outdoor recreation managers must recognize and accommodate these differences to provide

satisfactory experiences to a widely diverse clientele. Recreation specialization is

an area of study that attempts to describe this variation through segmentation of

participants into meaningful and identifiable subgroups. Bryan (1977) was the

first to conceptualize recreational specialization as a continuum of behavior from

the general to the particular, reflected by equipment and skills used and activity

setting preferences. The four levels of specialization he identified in a population

of trout anglers were occasional anglers, generalists, technique specialists, and

technique-setting specialists. Bryan (1977) suggested that more highly specialized anglers are part of a leisure social world with a shared sense of group identification derived from similar attitudes, beliefs, and experiences.

Recreation specialization studies following Bryan used a variety of classification techniques and variables to segment participants into specialization levels.

Some studies found that a single-item measure of specialization could be used to

segment participants. For example, Graefe (1980) noted that frequency of participation (i.e., avidity) was a useful surrogate for measuring angler specialization. He found that anglers who fished more frequently (i.e., were more specialized) had higher self-reported skill levels, participated in more diverse fishing

settings, and had a greater dependency on the resource. Ditton, Loomis, and Choi

(1992) also used avidity to segment recreational anglers into four specialization

levels. Similarly, Schreyer, Lime, and Williams (1984) used total number of river

runs as a means of classifying river users into six groups and found differences

between the groups in the type of prior river experience, motives for participation,

perceptions of conflict, and support for managerial regulations.

Other studies took a multidimensional approach to recreation specialization

by incorporating several variables into a specialization index. Chipman and Helfrich

(1988) concluded that investment, consumptive habits, and frequency of participation were important characteristics for determining specialization among anglers. Kauffman and Graefe (1984) used preferences for river characteristics to

segment canoeists into more-specialized and less-specialized groups. Fedler and

Ditton (1986) segmented anglers into levels of consumptive orientation based on

responses to statements regarding the importance of catching fish. Wellman,

Roggenbuck, and Smith (1982) used a specialization index based on equipment

investment, past experience, and centrality to lifestyle to segment anglers into

groups that reflect respondents attitudes toward depreciative behavior. Virden

and Schreyer (1988) constructed a specialization index to segment hikers based

on equipment and economic commitment, centrality to lifestyle, general experience, and past experience variables.

241

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

Using a variety of segmentation methods, recreation specialization studies

showed that more specialized users differed from less-specialized users on numerous attributes. These included motives for participation (Kauffman & Graefe,

1984; Schreyer et al., 1984), importance of nonactivity-specific elements (Fedler

& Ditton, 1986), preferences for management strategies (Chipman & Helfrich,

1988; Hammitt & McDonald, 1983), perceptions about crowding (Vaske, Donnelly,

& Heberlein, 1978), environmental preferences (Kauffman & Graefe, 1984;

Schreyer et al. 1984; Virden & Schreyer, 1988), equipment ownership and use

(Chipman & Helfrich, 1988; Wellman et al., 1982), and centrality to lifestyle

(Virden & Schreyer, 1988; Wellman et al., 1982). In general, these studies provided support for Bryans specialization concept, and greatly advanced the general understanding of diversity among outdoor recreation participants.

However, the lack of any empirical testing of recreation specialization remained an issue. As pointed out by Ditton et al. (1992), any attempt to test Bryans

framework for specialization was problematic because it was tautological (circular) in its reasoning; specialization level, defined in terms of behaviors and preferences, was then used to predict specialized behaviors and experiential preferences.

As a result, recreation specialization as a concept could never be empirically tested

because specialization and its subsequent propositions were both defined and

measured in the same terms (Ditton et al., 1992).

Ditton et al. (1992) initiated development of a testable theory that links recreation specialization with elements of social worlds as described by Unruh (1979).

Unruh (1979) defined a social world as an internally recognizable constellation

of actors, organizations, events and practices which have coalesced into a perceived sphere of interest and involvement for participants. According to this perspective, members of the same social world hold similar attitudes, beliefs, and

motivations that create a sense of group identity. Unruh (1979) further suggested

that members within a social world could be ordered along a theoretical dimension of involvement level based on four key characteristics: orientation, experiences, relationships, and commitment. For each characteristic, Unruh (1979) describes four involvement levels that correspond to four trans-situational social

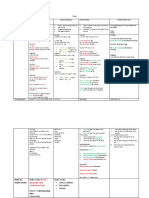

types: strangers, tourists, regulars, and insiders (Table 1).

Ditton et al. (1992) reconceptualized and redefined recreation specialization

TABLE 1 Characteristics and Types of Social World Participation (from Unruh,

1979)

Social types or subworlds

Characteristics

Strangers

Tourists

Regulars

Insiders

Orientation

Experiences

Relationships

Commitment

naivete

disorientation

superficiality

detachment

curiosity

orientation

transiency

entertainment

habituation

integration

familiarity

attachment

identity

creation

intimacy

recruitment

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

242

R. J. Salz et al.

as a process by which recreation social worlds and subworlds segment and intersect into new recreation subworlds, and the subsequent ordered arrangement of

these subworlds and their members along a continuum. Subworld types are arranged

by Ditton et al. (1992) on a continuum from least specialized to most specialized.

Ditton et al. (1992) developed eight recreation specialization propositions.

They tested three of these, using frequency of participation to segment anglers

into four specialization levels. Their results provided empirical support for specialization by showing that the four groups differed as predicted in their resource

dependency, level of mediated interaction, and the importance they attach to activity-specific and nonactivity-specific elements within a recreational activity.

Highly specialized anglers were found to have a higher resource dependency than

did less specialized anglers. The highly specialized groups placed more importance on catching big, distinctive, or trophy fish, whereas the less specialized

anglers appear to be less interested in the rare event aspect of the fishing experience. They found that anglers who were more specialized had a greater involvement in various types of mediated means of communication than did less specialized anglers. Finally, Ditton et al. (1992) found that as level of specialization

increased, the importance attached to catch-related angling motivations (e.g., catching fish of preferred size, number, or species) decreased relative to noncatch-related

angling motivations (e.g., to be outdoors, to relax, to be with friends, etc.).

Although their single dimension (i.e., frequency of participation) approach

to angler segmentation proved successful, Ditton et al. (1992) recognized that

other variables can and should be used as a means of classifying individuals into

specialization subgroups. A single variable (such as avidity) cannot adequately

measure these distinct dimensions of specialization and may result in high

misclassification rates. In this paper, we suggest that the testing of recreation specialization theory, and its application, is advanced when using a multivariable approach to segmentation that incorporates orientation, experiences, relationships,

and commitment.

Study Objectives

The first purpose of this research was to develop and validate a multivariable

specialization index based on a social world view of recreation specialization.

The second purpose of this research was to use this index to test recreation specialization theory by re-examining one of the propositions tested by Ditton et al.

(1992), examining two other propositions that have not yet been tested, and developing and testing a new proposition. The proposition to be retested states: as level

of specialization in a given recreation activity increases, the importance of activityspecific elements of the experience will decrease relative to nonactivity-specific

elements of the experience (Proposition Eight in Ditton et al., 1992). Ditton et al.

(1992) found that more-specialized anglers placed less importance on activityspecific elements, such as catching fish, and more importance on the nonactivity-

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

243

specific elements of the fishing experience, such as enjoying nature, relaxing,

being with friends or family, and so forth.

The second proposition states that participants who are more specialized would

indicate greater support for management rules and regulatory procedures, as well

as for social norms that identify and often dictate acceptable behavior, than would

less-specialized participants (Proposition Four in Ditton et al., 1992). Temporary

or seasonal closures due to overfishing, for example, would have a greater impact

for more-specialized individuals than for less-specialized individuals. Therefore,

by voluntarily accepting rules and social norms associated with the activity, participants help to ensure its continuation (Ditton et al., 1992). The third proposition states that more-specialized anglers have higher levels of side-bets than do

less-specialized anglers. Side-bets denote when something of value (time, money,

social relations) is invested in the activity with the condition that to discontinue

the activity could result in a loss of the investment (Alluto, Hrebiniak, & Alonso,

1973; Becker, 1960). More-specialized individuals are proposed to have a greater

financial and emotional investment in a given activity than less-specialized individuals (Proposition Two in Ditton et al., 1992).

The new proposition that we propose here states that as level of specialization in a given recreation activity increases, frequency of participation in that

activity will increase. We base this proposition on the results of previous research.

Graefe (1980) found avidity to be a surrogate measure for specialization level.

Schreyer et al. (1984) similarly used number of river runs to segment river users

into subgroups and found significant differences between these subgroups .

Chipman and Helfrich (1988) successfully used frequency of participation as one

element of determining specialization level. Finally, Ditton et al. (1992) used avidity

to segment a population of anglers into specialization subgroups, and found significant differences between the subgroups. We would view this as Proposition

Nine as added to the eight previously stated by Ditton et al. (1992).

Hypotheses

Based on the previous propositions, the following hypotheses were generated.

Ha1(a): High-specialization anglers will attach less importance to activity-specific elements of the fishing experience than will low-specialization

anglers.

Ha1(b): High-specialization anglers will attach more importance to nonactivityspecific elements of the fishing experience than will low-specialization

anglers.

Ha2:

High-specialization anglers will have a greater support for various management tools and regulations than will low-specialization anglers.

Ha3:

High-specialization anglers will have generated a greater value of sidebets than will low-specialization anglers.

Ha4:

High-specialization anglers will have a greater frequency of participation than will low-specialization anglers.

244

R. J. Salz et al.

Methods

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Specialization Index

In developing our specialization index, we chose to pursue an a priori approach

that builds on theory, and that uses theory to generate the index items. Our specialization index items, therefore, were derived from the four characteristics (orientation, experiences, relationships, and commitment) used by Unruh (1979) to

place participants in a particular subworld (or in our case a particular specialization level). For each characteristic, Unruh described four subworld types of participants: strangers, tourists, regulars, and insiders (Table 1). Based on these descriptions, we developed four survey questions (i.e., corresponding to the four

characteristics), each containing four possible response options (i.e., corresponding to four specialization levels). Question response options, consisting of statements describing a participants connection to an activity relative to that particular characteristic, were ordered from least specialized (response option = 1) to

most specialized (response option = 4) along a 4-point scale (Table 2). It was

expected that for each item, the least-specialized participants would select response option 1, and the most-specialized participants would select response option 4.

The sum of the four responses (e.g., least specialized: 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 4,

highly specialized: 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 = 16) was then used to locate anglers along the

recreation specialization continuum. The actual process of developing and testing

the specialization index used for segmentation of anglers into specialization levels is described in the Results section.

Data Collection

Data were collected by way of a mail survey administered to a random sample of

licensed Massachusetts anglers. The basic survey design and implementation followed accepted principles based on Salant and Dillman (1994). A personalized

advance-notice letter was sent to all members of the sample announcing they had

been selected to participate in the survey and that they would be receiving the

questionnaire in the mail within the following week. One week later a set of survey materials was mailed to all members of the sample. These materials included

the questionnaire, a cover letter describing the intent of the survey, and a selfaddressed stamped envelope for returning the completed survey. Two weeks after

mailing the advance notice letter, a thank you/reminder postcard was mailed to all

members of the sample. This follow-up served to thank those who had already

completed and returned their questionnaire, and to request a response from those

who had not. Five weeks after mailing the advance notice letter, a second set of

survey materials was sent to those who had not yet responded. This second survey

package was identical to the first, except that the personalized cover letter was

revised to further encourage the subject to complete and return their survey.

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

245

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

TABLE 2 Recreation Specialization Index Survey Questions and Response

Options

Q. Please indicate your general orientation to the sport of fishing.

1) I am an outsider. I am uncomfortable when I go fishing, and dont really feel

like I am part of the fishing scene.

2) I am an observer or irregular participant. Sometimes it is fun, entertaining, or

rewarding to go fishing.

3) I am a habitual and regular participant in the sport of fishing.

4) I am an insider to the sport. Fishing is an important part of who I am.

Q. Please indicate how you would best describe yourself during a fishing experience.

1) I am often uncertain. I am unsure about what I can or cannot do while fishing,

or how to do it.

2) I have some understanding of fishing, but I am still in the process of learning

more about fishing. I am becoming more familiar and comfortable with fishing.

3) I have become comfortable with the sport. I have regular, routine and predictable experiences. I have a good understanding of what I can do while fishing,

and how to do it.

4) I am a facilitator in the sport. I encourage, teach and enhance opportunities for

others who are interested in fishing.

Q. Please indicate how you would best describe your relationships with other

anglers.

1) Superficial. I really dont know any other anglers.

2) Very limited. I know some other anglers by sight and sometimes talk with

them, but I dont know their names.

3) One of familiarity. I know the names of other anglers, and often speak with

them.

4) Close. I have personal and close relationships with other anglers. These friendships often revolve around fishing.

Q. Please indicate how you would best describe your commitment to fishing.

1) Almost nonexistent. I am basically indifferent about going fishing.

2) Moderate commitment. I will continue to go fishing as long as it is entertaining and provides the benefits I want.

3) Fairly strong commitment. I have a sense of being a member of the activity,

and it is likely that I will continue to fish for a long time.

4) Very strong commitment. I am totally committed to fishing. I encourage others to go fishing and seek to ensure the activity continues into the future.

246

R. J. Salz et al.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Testing Specialization Theory

One-way ANOVA tests were used to test for mean differences between specialization groups. A significance level of .10 was used to test the null hypotheses.

This level of confidence reflects a balance between a higher probability of committing a Type I error (rejecting a true null hypothesis) and consequently decreasing the probability of committing a Type II error (failure to reject the null when it

is false). Gregorie and Driver (1979) suggest this as being a more appropriate

level (than 0.01 or 0.05), so later studies would not mistakenly consider some of

the insignificant differences as being unimportant, when in fact they might have

been due to the commission of a Type II error.

Results

Response Rate

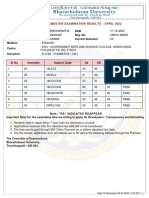

A total of 1,411 questionnaires (54.6%) were returned in usable form (Table 3).

There were 312 questionnaires returned as undeliverable by the U.S. Postal Service, 3 were returned because the addressee was deceased, and 29 returned by

respondents were unusable. The remainder were nonresponses.

Index Development and Internal Validation

Frequency distributions were calculated for each of the four index items (Figure

1). On a scale of responses from 1 (least specialized) to 4 (highly specialized), the modal response for all four items was 3. The proportion of responses

in the least-specialized category (i.e., response = 1) was 2% or less for orientation, experience, and commitment. The proportion of least-specialized responses (response = 1) was considerably greater for relationships (7.3%), although this was still small compared to the proportion for the other three response

TABLE 3 Status of Sport Angler Questionnaire Response

Type of response

Initial sample

Mortality

Deceased (3)

Nondeliverable (312)

Not-usable upon return (29)

Effective sample

Nonresponse

2,930

344

2,586

1,175

100.0

45.4

Usable returned surveys

1,411

54.6

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

247

FIGURE 1. Distribution of angler selections of response options according to the

four index items.

options. Nearly 60% of respondents chose 3 for the question regarding experience. The other variables were more evenly distributed across responses, except

for the previously noted lack of 1 responses (Figure 1).

Bivariate relationships among the items considered for inclusion in the index were then examined to determine the degree to which the items were related

(Babbie, 1995). Correlation coefficients for the six pair-wise comparisons ranged

from 0.41 to 0.60 and were all statistically significant (Table 4). This middle range

suggests that no two items were so similar as to warrant exclusion from the index

to avoid redundancy. Therefore, although significant positive relationships were

found for all pair-wise comparisons, each item measures a somewhat different

aspect of recreation specialization. The two lowest correlation coefficients involved the variable relationships (0.41 and 0.43), whereas the highest correlation was between orientation and commitment (0.60).

Another way to analyze bivariate relationships is to examine the percent of

occurrences when two variables differ from each other by more than a particular

amount. For each of our four variables, possible responses ranged from 1 (least

specialized) to 4 (highly specialized). For all pair-wise comparisons, less than

9% of all respondents had responses for any two variables that differed by more

than one (Table 4). This further supports the strong positive relationships between

all items. Most of the cases where an anglers responses for two variables did

differ by more than one involved the variable relationships. Pair-wise comparisons not involving the variable relationships differed by more than one for only

about 3% of respondents.

Index item reliability was tested using Cronbachs coefficient alpha

(Cronbach, 1951). The reliability of the final multiple-item index was measured

with an internal consistency coefficient (Cronbachs alpha) of 0.78. Alpha values

248

R. J. Salz et al.

TABLE 4 Bivariate Relationships Among Index Items

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Index item pair

Relationships and Experience

Relationships and Orientation

Relationships and Commitment

Experiences and Orientation

Experiences and Commitment

Orientation and Commitment

Correlation

coefficient

% of responses differing

by more than one

0.41

0.43

0.49

0.48

0.50

0.60

8.2%

8.9%

7.8%

3.0%

3.0%

3.0%

when a particular item was deleted were 0.68 for commitment, 0.74 for experience, 0.70 for orientation, and 0.76 for relationships. This further supported the

inclusion of all four recreation specialization social world characteristics (i.e.,

orientation, commitment, experience, and relationships) in our index.

Based on our results from the bivariate comparisons and Cronbachs alpha,

we decided to include all four items in creating our recreation specialization index. A composite specialization rank was calculated by summing the responses to

the four items for each respondent (Figure 2). Composite scores ranged from 4

through 16. Respondents were segmented into specialization groups based on

their cumulative item score as follows:

If cumulative score = 46 Index Level = 1 (least specialized)

If cumulative score = 710 Index Level = 2 (moderately specialized)

If cumulative score = 1113 Index Level = 3 (very specialized)

If cumulative score = 1416 Index Level = 4 (highly specialized)

FIGURE 2. Distribution of anglers according to cumulative index score.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

249

Again, we pursued an a priori process in developing the index. This also

applied to determining which item scores should correspond to which specialization levels. We chose to make the score brackets as equal in size as possible (levels 1, 3, and 4 all had a range of 3 in their score, whereas level 2 had a range of 4).

The number of anglers classified into each specialization level is the result of this

process, rather than the opposite in which some preconceived distribution of anglers is forced into a manipulated set of index brackets.

This process resulted in the least specialized angler group (Level = 1) accounting for only 1.2% (n = 16) of all respondents (Figure 3). Moderately specialized anglers (Level = 2) accounted for 32.5% (n = 440), very specialized

anglers (Level = 3) accounted for 42.3% (n = 572), and highly specialized anglers (Level = 4) accounted for 24.0% (n = 325) of all respondents.

Internal index validation is conducted to demonstrate that an index successfully measures what it is intended to measure (Babbie, 1995). A method of internal validation called item analysis was conducted to examine the extent to which

our composite index is related to (or predicts responses to) the four items (i.e.,

relationships, commitment, experience, and orientation) that comprise it. Item

analyses using direct comparisons were possible because both index scores (i.e.,

index level) and item scores were based on equivalent 4-point scales ranging from

least to highly specialized. The index score was identical to the item score for

orientation 72% of the time, commitment 74% of the time, experiences

66% of the time, and relationships 60% of the time. For all items, the absolute

difference between index score and item score exceeded one for less than 3% of

respondents. These results support the internal validity of our specialization index.

As a final test, correlations were computed between specialization index level

and more traditional measures of specialization such as avidity (freshwater days

fished in past 12 months) and total years fished. The correlation between special-

FIGURE 3. Distribution of anglers according to specialization level.

250

R. J. Salz et al.

ization index level and freshwater days fished in past 12 months was 0.38, whereas

the correlation between specialization index level and years fished was 0.18. Both

were highly significant (p < 0.0001), indicating that our specialization index correlates with these unidimensional specialization indicators. However, both correlations were also fairly low, suggesting that important differences between our

index and these unidimensional indicators do exist.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Testing Recreation Specialization Theory

As mentioned before, our segmentation of respondents resulted in only 16 individuals (1.2%) being classified into the least-specialized level. Because this is an

inadequate sample size for our analyses, this group was subsequently dropped for

hypothesis testing. Therefore, hypotheses were tested using only three specialization levels: Moderately specialized (M), Very specialized (V), and Highly specialized (H); levels 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Hypothesis One

Seven items were used to measure the importance of activity-specific elements of

the fishing experience. Results show significant differences for five of these seven

measures (Table 5). However, one of these items was contrary to specialization

theory because more-specialized anglers rated the item experience of the catch

as more important than did less-specialized anglers. For two other items, there

was no significant difference among specialization levels. Still, four out of the

five items with significant differences were ordered as predicted by specialization

theory. Based on these results, the null hypothesis that there are no differences

according to level of specialization on activity-specific measures of the fishing

experience was rejected, and we accept hypothesis Ha1(a) as stated, but propose

that more investigation is needed regarding the items that did not behave as predicted by specialization theory.

Ten items were used to measure the importance of nonactivity-specific elements of the fishing experience. Results show significant differences for 9 out of

the 10 items according to level of specialization (Table 6). It was predicted that

more-specialized anglers would place greater importance on nonactivity-specific

activities than would less-specialized anglers. Because the results are as predicted,

the null hypothesis is rejected and Ha1(b) is accepted as stated.

Hypothesis Two

Eleven items were used to measure support or opposition to various management

regulations. The null hypothesis, which states that there are no differences between anglers in their support and opposition to management rules, was rejected

because significant differences were found for ten of the eleven items (Table 7).

251

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

TABLE 5 One-way ANOVA Tests for Mean Differences in Importance of

Activity-specific Items According to Specialization Level

Level of specialization

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Items*

For the experience of

3.500** 3.818

the catch

For the sport of fishing,

3.556

3.904

not to obtain food to eat

Im just as happy if I

4.110

4.181

release the fish I catch

I am just as happy if I dont

4.053

4.158

keep the fish I catch

A fishing trip can be

3.792

3.834

successful even if no

fish are caught

When I go fishing, Im just

3.095

3.034

as happy if I dont catch

a fish

To obtain fish for eating, and 1.502

1.480

not for sport

4.128

30.29

0.000

4.183

26.11

0.000

4.370

7.57

0.001

4.329

7.55

0.001

4.031

5.90

0.003

3.111

0.67

0.510

1.547

0.55

0.578

*For items 1, 2, and 7 mean scores were based on responses to the following categories;

1 = Not at all important, 2 = Slightly important, 3 = Moderately important, 4 = Very

important, 5 = Extremely important. For all other items, mean scores were based on

responses to the following categories; 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4

= Agree, 5 = Strongly agree.

**Means underscored by same line are not significantly different (.10) using Tukeys

test.

The prediction that more-specialized anglers would indicate a greater support for

management rules than would less-specialized anglers was supported on 9 of the

10 significant items. The mean values for one item (restricted fishing area) were

directly opposite of that predicted. Because 9 of the 10 significant items were

ordered as predicted, Ha2 is accepted as stated.

Hypothesis Three

Four items relating to the cost of replacing fishing equipment were used to measure side-bets. It was predicted that more-specialized anglers would generate a

greater value in side-bets than would less-specialized anglers. Significant differences supporting this prediction were found according to specialization level for

all four items (Table 8). Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis. Because the

mean differences are as predicted, we accept Ha3 as stated.

252

R. J. Salz et al.

TABLE 6 One-way ANOVA Tests for Mean Differences in Importance of

Nonactivity-specific Items According to Specialization Level

Level of specialization

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Items*

To experience adventure

and excitement

To be close to the water

For relaxation

To be with friends

To experience natural

surroundings

To experience new and

different things

To get away from the

demands of other people

To be outdoors

To get away from

the regular routine

For family recreation

3.405**

3.732

4.009

28.77

0.000

3.366

4.218

3.107

4.134

3.576

4.345

3.206

4.248

3.973

4.559

3.559

4.453

21.20

16.48

13.21

12.82

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

2.842

2.939

3.279

12.35

0.000

3.409

3.474

3.842

10.49

0.000

4.177

3.800

4.236

3.912

4.450

4.159

10.44

9.78

0.000

0.000

3.279

3.136

3.256

1.72

0.179

*Mean scores were based on responses to the following categories; 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Slightly important, 3 = Moderately important, 4 = Very important, 5 = Extremely

important.

**Means underscored by same line are not significantly different (.10) using Tukeys

test.

Hypothesis Four

Results showed significant differences on angler frequency of participation according to level of specialization (Table 9). The null hypothesis is therefore rejected as stated. Highly-specialized anglers had significantly higher rates of participation than did moderately-specialized anglers, who in turn had significantly

higher rates of participation than did lower-specialized anglers. Because this is

consistent with what was predicted, Ha4 is accepted as stated.

Discussion

Our results provide strong support for the theory of recreation specialization as

reconceptualized by Ditton et al. (1992), and for use of the specialization index

developed here. Results from our hypotheses tests were as predicted for an overwhelming majority of the items we investigated. Our study also strongly supports

the inclusion of all four characteristics of social worlds (commitment, orienta-

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

253

TABLE 7 One-way ANOVA Tests for Mean Differences in Support and

Opposition of Management Regulation Items According to Specialization Level

Level of specialization

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Items*

Creel limit

No stocking allowed

Maximum size

Stock non-native fish

Minimum size limit

Restricted fishing area

Mandatory catch

and release

Stock native fish

Slot limit

Voluntary catch and

release

Prohibit use of certain

gear

4.109**

3.559

3.284

3.009

4.108

3.434

3.122

4.293

3.673

3.547

3.282

4.211

3.260

3.162

4.463

3.935

3.733

3.343

4.433

3.069

3.439

14.79

13.70

13.64

11.13

8.62

7.23

6.67

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.001

0.001

4.219

3.117

3.874 a

4.336

3.190

4.028 b

4.403

3.388

4.022 a,b

6.03

5.86

2.83

0.003

0.003

0.059

3.612

3.545

3.581

0.43

0.653

*Mean scores were based on responses to the following categories; 1 = Strongly oppose,

2 = Oppose, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Support, 5 = Strongly support.

**Means underscored by same line or same superscript are not significantly different

(.10) using Tukeys test.

tions, experience, and relationships) as related and reliable measures of recreation

specialization.

Specialization Index Development

There are several possible explanations for the fact that the least specialized

subworld made up such a small proportion of our sample (only 1.2%). First, we

should not rule out the possibility that this group may, in fact, be much smaller in

size than the other groups. This would be the case if the learning curve from least

specialized to moderately specialized requires a relatively short time period.

Because our survey was administered to those people who had purchased licenses

during the previous year, anglers who were least specialized at the time of license purchase had at least a full fishing season to increase their specialization

level prior to receiving our survey. Another possible explanation is that our sample

did not tap into those groups of anglers that make up the majority of the least

specialized group. For example, children (under 17 years old), out-of-state anglers, and 3-day license holders were not part of our survey population. One might

reasonably expect these anglers to be among the least specialized. We consider

254

R. J. Salz et al.

TABLE 8 One-way ANOVA Tests for Mean Differences in the Cost of Replacing

Fishing Equipment with Similar Equipment Between Specialization Level

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Items*

Replace reels

Replace tackle

Replace rods

Replace electronic

equipment

Level of specialization

M

V

H

$119.33*

114.80

138.31

262.00

$229.49

282.28

284.52

436.65

$455.80

579.84

555.28

580.42

90.00

78.65

38.18

6.95

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.001

*Means underscored by same line are not significantly different (.10) using Tukeys test.

these explanations to be the most likely reasons for the small size of the least

specialized group.

Nonresponse bias could also be a possible explanation if the probability of

an angler returning our survey was positively correlated to the anglers specialization level. However, in a study of nonresponse bias on angler surveys, Fisher

(1996) found that species preferences and scores from summated Likert scales

were independent of response probabilities. Finally, the choice of words we used

for the least specialized response options could explain the low percent of respondents selecting those options. Anglers may have felt embarrassed to identify

themselves with words such as outsider, uncomfortable, unsure or uncertain, all of which may have strong negative connotations. Our results suggest

that least specialized subworlds may be more difficult to sample for a variety of

reasons. A special sample design may be needed in certain situations to adequately

address this group.

Our results showed that although all four social world characteristics (relationships, orientation, experience, and commitment) should be included in the

index, the relationships dimension behaved somewhat differently from the other

three. Specifically, some anglers scored least specialized for relationships but

were in the middle-to-high range of specialization for the other three dimensions.

This suggests that for the activity of freshwater fishing, having personal relationTABLE 9 One-way ANOVA Tests for Mean Differences in Frequency of

Participation According to Specialization Level

Level of specialization

Items*

Mean total days

fished

15.566*

36.656

56.609

105.54

0.000

*Means underscored by same line are not significantly different (.10) using Tukeys test.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

255

ships with other anglers may not be as important of a component when advancing

to higher specialization levels as previously thought. Although interaction and

communication relate to social world boundaries (Unruh, 1980), in todays world

these can be readily achieved through mediated channels instead of personal contact. Some highly specialized anglers may rely on journals, magazines, cable television, and the Internet to acquire and exchange information about fishing. If so,

our question measuring relationships, which focuses only on personal contacts,

may have to be expanded to include a wider range of interactive and communicative possibilities.

The characteristics included in our index were derived directly from the social worlds literature. Still, the question of which specific measures should be

used to define specific characteristics of a specialization index is open to interpretation (Kuentzel & McDonald, 1992). For example, commitment to an activity

has been measured as the number of related magazines one subscribes to (Bloch,

Black, & Lichtenstein, 1989), the level of activity involvement (Williams &

Huffman, 1986), the centrality of the activity to ones lifestyle (Chipman &

Helfrich, 1988), the number of side-bets invested in, and an affective attachment to the activity (Buchanan, 1985). Similarly, one could come up with multiple ways to define and measure orientation, experience, and relationships

related to a particular activity.

Specialization dimensions can also be measured using either behavioral or

cognitive measures. One of the main features of social world involvement is voluntary identification, meaning one chooses to become a member of a social world

rather than it being a requirement (Unruh, 1980). The necessity of voluntary identification suggests a strong cognitive component to entry into a social world and

movement between subworlds within that social world. This cognitive component is reflected in the questions we used in this study to measure specialization

dimensions. For example, rather than measure commitment through other variables as described above, anglers were asked directly to choose the statements

that best describe their involvement in the sport.

Approaching specialization from a social worlds perspective may add subjectivity to the index because words like commitment, insider, and orientation can mean different things to different people. However, this subjectivity

does not necessarily bias the segmentation process, but rather, it may redefine

specialization in a new way. The assumption that a specialization index derived

from objective measures (i.e., gear used, days fished, magazines purchased) is

preferable to one that uses more subjective, cognitive measures should not automatically be made. The decision of which index to use should, perhaps, be based

on the goals of the particular study and the research purpose or management application it is intended for. The general lack of consistency in measuring specialization in the outdoor recreation literature supports this contention. For future

study, it would be interesting to compare participant segmentation using our index with previous specialization indices using the same survey population.

256

R. J. Salz et al.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

Testing Recreation Specialization Theory

Results indicated that more-specialized anglers were more interested in a qualitative experience, whereas less-specialized anglers had a more simplistic view of

fishing that did not consider other intrinsic elements of the experience to be quite

as important. This supports specialization theory and further reconfirms the results of Ditton et al. (1992).

Frequency of participation was also shown to increase as specialization levels increase. Our results are consistent with previous work and justify the addition

of our proposed Proposition Nine. Individuals are likely to increase their frequency of participation when they feel some sort of attachment to an activity. As

specialization level increases, alternative activities will be rejected as the commitment to participating in the primary activity increases (Buchanan, 1985; Unruh,

1979).

It appears that more-specialized anglers are more receptive to management

regulations than are less-specialized anglers. The support for management regulations was shown to increase as specialization increases. The former group is

more likely to be impacted than the latter group if fishing activities were discontinued; therefore, as predicted from specialization theory, the former would be

more supportive of rules and regulations issued from fisheries management

agencies.

Finally, as predicted, side-bets anglers appropriated for fishing equipment

were shown to increase as level of specialization increased. Because of a greater

involvement within the activity, more-specialized anglers will commit greater financial costs towards fishing than will less-specialized anglers.

Management Implications

There is potential here for fisheries managers to gain an understanding of group

differences on a variety of issues to efficiently improve services already provided.

By developing and promoting services based on some aggregation of anglers, the

interests of many anglers are ignored. Managers may then be confronted with a

fairness issue, where some anglers perceive that resources are allocated unfairly.

Segmentation by specialization recognizes that different groups have different

attributes that require different marketing schemes. Through a better understanding of the angling constituency, managers can avoid making resource allocation

decisions that may result in the loss of credibility for the fisheries agency (Ditton,

1996; Loomis & Ditton, 1993). The results of this study provide strong support

for the use of a multidimensional index as a means of classifying participants into

homogeneous groups, based on the recreation specialization theory developed by

Ditton et al. (1992). Such insight to anglers can also be used to effectively evaluate current management objectives and services.

Development and Validation of a Specialization Index

257

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

References

Alluto, J. A., Hrebiniak, L. G., & Alonso, R. C. (1973). On operationalizing the concept

of commitment. Social Forces, 51, 448454.

Babbie, E. (1995). The practice of social research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing

Company.

Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66, 3240.

Bloch, P. H., Black, W. C., & Lichtenstein, D. (1989). Involvement with the equipment

component of sport: Links to recreational commitment. Leisure Sciences, 11, 187

200.

Bryan, H. (1977). Leisure value systems and recreational specialization: The case of trout

fishermen. Journal of Leisure Research, 9(3), 174187.

Buchanan, T. (1985). Commitment and leisure behavior: A theoretical perspective. Leisure Sciences, 7, 401420.

Chipman, B. D., & Helfrich, L. A. (1988). Recreational specialization and motivations of

Virginia river anglers. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 8, 390

398.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika,

16, 297334.

Ditton, R. B. (1996). Understanding the diversity among largemouth bass anglers. American Fisheries Society Symposium, 16, 135144.

Ditton, R. B., Loomis, D. K., & Choi, S. (1992). Recreation specialization:

Reconceptualization from a social worlds perspective. Journal of Leisure Research,

24(1), 3551.

Fedler, A. J., & Ditton, R. B. (1986). A framework for understanding the consumptive

orientation of recreational fishermen. Environmental Management, 10(2), 221227.

Fisher, M. R. (1996). Estimating the effect of nonresponse bias on angler surveys. Transaction of the American Fisheries Society, 125, 118126.

Graefe, A. R. (1980). The relationship between level of participation and selected aspects of specialization in recreational fishing. Doctoral dissertation. Texas A&M

University, College Station.

Gregorie, T. G., & Driver, B. L. (1987). Type II errors in leisure research. Journal of

Leisure Research, 19(4), 261272.

Hammitt, W. E., & McDonald, C. D. (1983). Past on-site experience and its relationship

to managing river recreation resources. Forest Science, 29, 262266.

Kauffman, R. B., & Graefe, A. R. (1984). Canoeing specialization, expected rewards, and

resource related attitudes. In J. S. Popodic, D. I. Butterfield, D. H. Anderson, & M.

R. Popodic (Eds.), National River Recreation Symposium Proceedings (pp. 629

641). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University.

Kuentzel, W. F., & McDonald, C. D. (1992). Differential effects of past experience, commitment, and lifestyle dimensions of river use specialization. Journal of Leisure

Research, 24, 269287.

Loomis, D. K., & Ditton, R. B. (1993). Distributive justice in fisheries management.

Fisheries, 18, 1418.

Salant, P., & Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your own survey. New York: Wiley.

Downloaded by [Fac Psicologia/Biblioteca] at 00:20 25 September 2012

258

R. J. Salz et al.

Schreyer, R. M., Lime, D. W., & Williams, D. R. (1984). Characterizing the influence of

past experience on recreation behavior. Journal of Leisure Research, 16, 3450.

Unruh, D. R. (1979). Characteristics and types of participation in social worlds. Symbolic

Interaction, 2, 115130.

Unruh, D. R. (1980). The nature of social worlds. Pacific Sociological Review, 23(3),

271296.

Vaske, J. J., Donnelly, M. P., & Heberlein, T. A. (1978). Perceptions of crowding and

resource quality by early and more recent visitors. Leisure Sciences, 3, 367381.

Virden, R. J., & Schreyer, R. M. (1988). Recreation specialization as an indicator of

environmental preference. Environment and Behavior, 20, 721739.

Wellman, J. D., Roggenbuck, J. W., & Smith, A. C. (1982). Recreation specialization and

norms of depreciative behavior among canoeists. Journal of Leisure Research, 14,

323340.

Williams, D. R., & Huffman, M. G. (1986). Recreation specialization as a factor in

backcountry trail choice. In R. Lucas (Ed.) Proceeding of the National Wilderness

Research Conference Current Research, (General Technical Report INT-211, pp.

339344), Ogden, UT: USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Fase PrácticaDokumen2 halamanFase Prácticasir3liotBelum ada peringkat

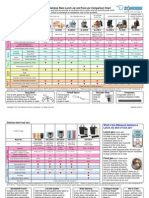

- Zojirushi Lunch Jar ChartDokumen2 halamanZojirushi Lunch Jar Chartsir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Basque Energy Board (Eve)Dokumen5 halamanBasque Energy Board (Eve)sir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- 11287846-64de51-G16 - Islandsk Barntroja Med Pingviner I LettlopiDokumen3 halaman11287846-64de51-G16 - Islandsk Barntroja Med Pingviner I Lettlopisir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- The Vermonter Hat PDFDokumen1 halamanThe Vermonter Hat PDFsir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- The Elder Tree Shawl PDFDokumen5 halamanThe Elder Tree Shawl PDFsir3liot100% (2)

- Light and Up: MaterialsDokumen3 halamanLight and Up: Materialssir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Cloudburst Shawl: NotionsDokumen7 halamanCloudburst Shawl: Notionssir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- ChristiansHat ENG PDFDokumen2 halamanChristiansHat ENG PDFsir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Phannie: Crocheted in - Skill LevelDokumen3 halamanPhannie: Crocheted in - Skill Levelsir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Lalasimpleshawl Eng-2 PDFDokumen1 halamanLalasimpleshawl Eng-2 PDFsir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Peace Fleece Lacy Beret: MaterialsDokumen2 halamanPeace Fleece Lacy Beret: Materialssir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- Light and Up: MaterialsDokumen3 halamanLight and Up: Materialssir3liotBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Analytical Solution For A Double Pipe Heat Exchanger With Non Adiabatic Condition at The Outer Surface 1987 International Communications in Heat and MDokumen8 halamanAnalytical Solution For A Double Pipe Heat Exchanger With Non Adiabatic Condition at The Outer Surface 1987 International Communications in Heat and MDirkMyburghBelum ada peringkat

- BHUVANESHWARI M (CB21C 82639) - Semester - Result (1) 22Dokumen1 halamanBHUVANESHWARI M (CB21C 82639) - Semester - Result (1) 22AllwinBelum ada peringkat

- AAU Training ProgramsDokumen44 halamanAAU Training ProgramskemimeBelum ada peringkat

- Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University, Bareilly: Examination Session (2021 - 2022)Dokumen2 halamanMahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University, Bareilly: Examination Session (2021 - 2022)Health AdviceBelum ada peringkat

- DirectingDokumen17 halamanDirectingDhyani Mehta100% (1)

- Fianl Attaindance 1.0Dokumen2 halamanFianl Attaindance 1.0Chandan KeshriBelum ada peringkat

- Early Childhood DevelopmentDokumen100 halamanEarly Childhood DevelopmentJoviner Yabres LactamBelum ada peringkat

- Akhuwat Micro Finance BankDokumen8 halamanAkhuwat Micro Finance BankAmna AliBelum ada peringkat

- PERSONAL FITNESS PLAN TemplateDokumen2 halamanPERSONAL FITNESS PLAN TemplateAnalytical ChemistryBelum ada peringkat

- 3 - U2L1-The Subject and Content of Art-AAPDokumen5 halaman3 - U2L1-The Subject and Content of Art-AAPFemme ClassicsBelum ada peringkat

- Noam Chomsky: A Philosophic Overview by Justin Leiber - Book Review by Guy A. DuperreaultDokumen3 halamanNoam Chomsky: A Philosophic Overview by Justin Leiber - Book Review by Guy A. DuperreaultGuy DuperreaultBelum ada peringkat

- RLIT 6310.90L Children's and Adolescent Literature: Textbook And/or Resource MaterialDokumen10 halamanRLIT 6310.90L Children's and Adolescent Literature: Textbook And/or Resource MaterialTorres Ken Robin DeldaBelum ada peringkat

- About VALSDokumen3 halamanAbout VALSMara Ioana100% (2)

- JBI Nationwide 2023 Group of SubrabasDokumen6 halamanJBI Nationwide 2023 Group of SubrabasDonnabel BicadaBelum ada peringkat

- Ogl 320 FinalDokumen4 halamanOgl 320 Finalapi-239499123Belum ada peringkat

- Verb 1 Have V3/Ved Have Broken Have Gone Have Played V3/Ved Has Broken Has Gone Has WorkedDokumen3 halamanVerb 1 Have V3/Ved Have Broken Have Gone Have Played V3/Ved Has Broken Has Gone Has WorkedHasan Batuhan KüçükBelum ada peringkat

- English: Quarter 4 - Module 4: Reading Graphs, Tables, and PictographsDokumen23 halamanEnglish: Quarter 4 - Module 4: Reading Graphs, Tables, and PictographsResica BugaoisanBelum ada peringkat

- Form For Curriculum Vitae (CV) For Proposed Key PersonnelDokumen2 halamanForm For Curriculum Vitae (CV) For Proposed Key PersonnelAnuj TomerBelum ada peringkat

- Deep Learning Interview Questions and AnswersDokumen21 halamanDeep Learning Interview Questions and AnswersSumathi MBelum ada peringkat

- Teste Simple Past Regular VerbsDokumen4 halamanTeste Simple Past Regular VerbsBorboletalindaBelum ada peringkat

- Stem Activity Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanStem Activity Lesson Planapi-668801294Belum ada peringkat

- Reflection Papers 7Dokumen12 halamanReflection Papers 7Shiela Marie NazaretBelum ada peringkat

- MCSci1 OBE SYLLABUSDokumen9 halamanMCSci1 OBE SYLLABUSBea Marie OyardoBelum ada peringkat

- Scope of Guidance - NotesDokumen2 halamanScope of Guidance - NotesDr. Nisanth.P.MBelum ada peringkat

- Cengiz Can Resume 202109Dokumen2 halamanCengiz Can Resume 202109ismenhickime sBelum ada peringkat

- Lac SessionDokumen11 halamanLac SessionANDREA OLIVASBelum ada peringkat

- Eng4 q1 Mod3 Notingdetails v3Dokumen19 halamanEng4 q1 Mod3 Notingdetails v3carlosBelum ada peringkat

- First Term Final Exam: 2. Complete The Conditional Sentences (Type I) by Putting The Verbs Into The Correct FormDokumen2 halamanFirst Term Final Exam: 2. Complete The Conditional Sentences (Type I) by Putting The Verbs Into The Correct FormRonaldEscorciaBelum ada peringkat

- BLRPT Review DrillsDokumen40 halamanBLRPT Review DrillsLemmy Constantino DulnuanBelum ada peringkat

- Diasporic Sensibilities in Jhumpa Lahiri's WorksDokumen2 halamanDiasporic Sensibilities in Jhumpa Lahiri's WorksMd. Sheraz ButtBelum ada peringkat