Investigating Internet Relationships PDF

Diunggah oleh

TionaTionaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Investigating Internet Relationships PDF

Diunggah oleh

TionaTionaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Category: Social Computing

2249

Investigating Internet Relationships

Monica T. Whitty

Queens University Belfast, UK

IntroductIon

The focus on Internet relationships has escalated in recent

times, with researchers investigating such areas as the development of online relationships (e.g., McCown, Fischer, Page,

& Homant, 2001; Parks & Roberts, 1998; Whitty & Gavin,

2001), the formation of friends online (Parks & Floyd, 1996),

representation (Bargh, McKenna, & Fitzsimons 2002), and

misrepresentation of self online (Whitty, 2002). Researchers

have also attempted to identify those addicted to accessing

online sexual material (Cooper, Putnam, Planchon, & Boies,

1999). Moreover, others have been interested in Internet

infidelity (Whitty, 2003a, 2005) and cybersex addiction

(Griffiths, 2001, Young, Griffin-Shelley, Cooper, OMara,

& Buchanan, 2000). Notwithstanding this continued growth

of research in this field, few researchers have considered the

new ethical implications of studying this topic area.

While it is acknowledged here that some of the discussions in this article might be equally applied to the study of

other Internet texts, such as religious or racial opinions, the

focus in this article is on the concomitant ethical concerns

of ongoing research into Internet relationships. Given that

the development and maintenance of online relationships

can be perceived as private and very personal (possibly

more personal than other sensitive areas), there are potential

ethical concerns that are unique to the study of such a topic

area (Whitty, 2004; Whitty & Carr, 2006). For a broader

discussion of virtual research ethics in general, refer to Ess

and Jones (2004) and Whitty and Carr (2006).

Background

Early research into this area has mostly focused on the similarities and differences between online and off-line relationships. Researchers have been divided over the importance

of available social cues in the creation and maintenance of

online relationships. Some have argued that online relationships are shallow and impersonal (e.g., Slouka, 1995). In

contrast, others contend that Internet relationships are just

as emotionally fulfilling as face-to-face relationships, and

that any lack of social cues can be overcome (Lea & Spears,

1995; Walther, 1996). In addition, researchers have purported

that the ideals that are important in traditional relationships, such as trust, honesty, and commitment, are equally

important online, but the cues that signify these ideals are

different (Whitty & Gavin, 2001). Current research is also

beginning to recognize that online relating is just another

form of communicating with friends and lovers, and that

we need to move away from considering these forms of

communication as totally separate and distinct entities (e.g.,

Wellman, 2004). Moreover, McKenna, Green, and Gleason

(2002) have found that when people convey their true self

online they develop strong Internet relationships and bring

these relationships into their real lives.

Internet friendships developed in chat rooms, newsgroups, and MUDs or MOOs have been examined by a

number of researchers. For example, Parks and Floyd (1996)

used e-mail surveys to investigate how common personal

relationships are in newsgroups. After finding that these relationships were regularly formed in newsgroups, Parks and

Roberts (1998) turned to examine relationships developed

in MOOs. These researchers found that most (93.6%) of

their participants had reported having formed some type of

personal relationship online, the most common type being

a close friendship.

Researchers have also been interested in how the playful

arena of the Internet impacts on the types of relationships

formed in these places (e.g., Whitty, 2003b; Whitty & Carr,

2003, 2006). Turkles (1995) well-known research on her

observations while interacting in MUDs found that the roleplaying aspect of MUDs actually creates opportunities for

individuals to reveal a deeper truth about themselves. Whitty

and Gavin (2001) have also contended that although people

do lie about themselves online, this paradoxically can open

up a space for a deeper level of engagement with others.

Importantly, some researchers are now starting to realize

that cyberspace is not a generic space that everyone experiences in the same way. New theories are currently being

developed to explain how individuals present themselves

in different spaces online. For instance, Whitty (in press)

devised the BAR theory to explain presentation of self on

online dating sites, which she believes is different to other

spaces within cyberspace. The BAR theory purports that most

online daters find the best strategy for developing a successful profile is to create a balance between an attractive self

and a real self. The online daters Whitty and her research

assistants interviewed (see Whitty, in press; Whitty & Carr,

2006) talked about the need to re-write their profiles if they

were attracting either people they did not desire, or if they

were attracting no one, or if their date appeared disappointed

with them when they met face-to-face (given that they did

not live out to their profile). Therefore, it would seem that

Copyright 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Investigating Internet Relationships

a successful profile has to appear attractive enough to stand

out and be chosen, but also one that individuals could live

up to in their first face-to-face date (which often took place

within a couple of weeks of meeting online).

Cybersex addiction and the available treatment for these

cybersex addicts and their partners has been an area of research and concern for psychologists (e.g., Schneider, 2000;

Young, Pistner, OMara, & Buchanan, 1999). Research has

also focused on what online acts might be considered as an

act of infidelity. For example, Whitty (2003a) found that

acts such as cybersex and hot-chatting were perceived as

almost as threatening to the off-line relationship as sexual

intercourse. In addition to these concerns, Cooper et al.

(1999) identified three categories of individuals who access

Internet erotic material, including recreational users, sexual

compulsive users (these individuals are addicted to sex per

se, and the Internet is but one mode where they can access

sexual material), and at-risk users (these individuals would

never have developed a sexual addiction if it were not for

the Internet).

ethIcal ISSueS pertInent to the

Study oF Internet relatIonShIpS

Much of the research, to date, on Internet relationships

and sexuality has been conducted onlineeither through

interviews, surveys, or by carrying out analysis on text

that is readily available online. There are many advantages

to conducting research online as well as collecting text or

data available online for analysis in ones research (see

Table 1).

In spite of the numerous advantages to conducting

research online, investigators also need to be aware of the

disadvantages (see Table 2).

What all studies that research Internet relationships have

in common is that they are researching a sensitive topic, which

requires individuals to reveal personal and often very private

aspects of themselves and their lives. Given the sensitive

nature of this topic area, it is crucial that researchers give

some serious thought to whether they are truly conducting

research in an ethical manner.

Table 1. Practical benefits of conducting research online

2250

Easy access to a population of individuals who form relationships online and who access sexual material

Internet provides researchers with a population that is sometimes

difficult to research (e.g., people with disabilities, agoraphobia)

Contact people in locations that have closed or limited access

(e.g., prisons, hospitals)

Requires relatively limited resources

Ease of implementation

Photographs, video, sound bites, and text produced by

individuals online are sometimes examined by researchers.

The text can be produced in a number of different forums,

including chat rooms, MUDs, newsgroups, MySpace, Bebo,

and online dating sites. One way researchers collect data

is by lurking in these different spaces in cyberspace. The

development of online relationships (both friendships and

romantic) and engaging in online sexual activities, such as

cybersex, could easily be perceived by those engaging in such

activities as a private discourse. Given the nature of these

interactions, social researchers need to seriously consider

if they have the right to lurk in online settings in order to

learn more about these activitiesdespite the benefits of

obtaining this knowledge.

There are fuzzy boundaries between what constitutes

public and private spaces online, and researchers need to

acknowledge that there are different places within cyberspace.

For example, a chat room might be deemed a more public

space than e-mail. It is contended here that lurking in some

spaces online might be ethically questionable. We must, as

researchers, debate how intrusive a method lurking potentially

is. As Ferri (1999, cited in Mann & Stewart, 2000) contends,

who is the intended audience of an electronic communicationand does it include you as a researcher? (p. 46).

Researchers also need to consider how the participant

perceives the various online spaces. As Ferri suggests, private

interactions can and do indeed occur in public places. It has

been theorized that the Internet can give an individual a sense

of privacy and anonymity (e.g., Rice & Love, 1987; Whitty

& Carr, 2006). The social presence theory contends that

social presence is the feeling one has that other persons

are involved in a communication exchange (Rice & Love,

1987). Since computer-mediated-relating (CMR) involves

less non-verbal cues (such as facial expression, posture,

and dress) and auditory cues in comparison to face-to-face

communication, it is said to be extremely low in social

presence. Hence, while many others might occupy the

space online, it is not necessarily perceived in that way. As

researchers we need to ask some questions: Can researchers ethically take advantage of these peoples false sense

of privacy and security? Is it ethically justifiable to lurk in

these sites and download material without the knowledge or

consent of the individuals who inhabit these sites? This is

especially relevant to questions of relationship development

and sexuality, which are generally understood to be private

Table 2. Disadvantages of conducting research online

Security issues

Possible duplication of participants completing surveys

Difficult to ascertain how the topic area examined impacts

on the participant

Restricted to a certain sample

Investigating Internet Relationships

matters. Therefore, good ethical practice needs to consider

the psychology of cyberspace and the false sense of security

the Internet affords.

It is suggested here that researchers need to maintain

personal integrity as well as be aware of how their online

investigations can impact the Internet relationships they

study. For example, given researchers knowledge of online

relationships, interacting on online dating sites, chat rooms,

and so forth could potentially alter the dynamics of these

communities.

While it might be unclear as to how ethical it is for lurkers to collect data on the Internet, there is less doubt as to

whether it is acceptable to deceive others online in order to

conduct social research, especially with respect to online

relationships and sexuality. Ethical guidelines generally

state that deception is unethical because the participant is

unable to give free and fully informed consent. For example,

according to the Australian National Health and Medical

Research Council (NHMRC), which set the ethical guidelines

for Australian research:

As a general principle, deception of, concealment of the

purposes of a study from, or covert observation of, identifiable participants are not considered ethical because they

are contrary to the principle of respect for persons in that

free and fully informed consent cannot be given. (NHMRC,

1999)

Generally, ethical guidelines will point out that only

under certain unusual circumstances deception is unavoidable when there is no alternative method to conduct ones

research. However, in these circumstances individuals must

be given the opportunity to withdraw data obtained from

them during the research that they did not originally give

consent to.

Future trendS

As with any other research conducted within the social sciences, some important ethical practices need to be adhered

to when we conduct research on Internet relationships and

sexuality (see Table 3).

Informed consent requires researchers to be up front

from the beginning about the aims of their research and

how they are going to be utilizing the data they collect. In

Table 3. Ethical practices

Informed consent

Withdrawal of consent

Confidentiality

Psychological safeguards

off-line research individuals often sign a form to give their

consent; however, this is not always achievable online. One

way around this is to direct participants to a Web site that

contains information about the project. This Web site could

inform the participants about the purpose of the study, what

the study entails, as well as contact details of the researcher,

and the university Human Ethics Committee.

In some cases, spaces on the Web are moderated. In

these instances, it is probably also appropriate to contact

the moderators of the site prior to contacting the participants. This is analogous to contacting an organization prior

to targeting individuals within that organization. Wysocki

(1998), for instance, asked permission from the moderator of

a sadomasochist bulletin board called the pleasure pit.

Researchers also need to be aware that some European

countries require written consent. If written consent is required, then the participant could download a form and sign

it off-line and then return it by fax or postal mail (Mann &

Stewart, 2000).

In research about relationships and sexuality, in particular,

there is the risk that the interview or survey will stress the

participant too much for them to continue with the study. As

with off-line research, researchers need to consider up until

what point a participant can withdraw consent. The end point

of withdrawal of consent might be, for instance, after the

submitting of the survey, or at the conclusion of the interview

the interviewer might find confirmation that the participant

is happy to allow the researcher to include the transcript in

the study. Social scientists should also be aware that the lack

of social cues available online makes it more difficult for

them to ascertain if the participant is uncomfortable. Thus

one should tread carefully and possibly make an effort to

check at different points in the interview if the individual is

still comfortable with proceeding.

There are other issues unique to Internet research in

respect to withdrawal of consent. For example, the computer

could crash mid-way through an interview or survey. Mechanisms need to be put into place to allow that participant to

re-join the research if desired, and consent should not be

assumed (Buchanan & Smith, 1999). In circumstances such

as the computer or server crashing, we might need to have

a system to enable debriefing, especially if the research is

asking questions of a personal nature. Nosek, Banaji, and

Greenwald (2002) suggest that debriefing can be made available by providing a contact e-mail address at the beginning

of the study. They also suggest providing a leave the study

button, made available on every study page, [which] would

allow participants to leave the study early and still direct

them to a debriefing page (p. 163). In addition, they state

that participants be given a list of FAQs, since they argue

that there is less opportunity to ask the sorts of questions

participants typically ask in face-to-face interviews.

There are various ways we might deal with the issue of

confidentiality. As with off-line research we could elect to

2251

Investigating Internet Relationships

use pseudonyms to represent our participants or even request

preferred pseudonyms from them. However, a unique aspect

of the Internet is that people typically inhabit the Web using

a screen name, rather than a real name. Can we use a screen

name given that these are not real names? While they may

not be peoples off-line identities, individuals could still be

identified by their screen names if we publish themeven

if it is only recognition by other online inhabitants.

As mentioned earlier in this article, research into the areas

of relationships and sexuality is likely to cause psychological

distress for some. It is perhaps much more difficult to deal

with psychological distress online and with individuals in

other countries. Nevertheless, it is imperative that we ensure

that the participant does have counseling available to them

if the research has caused them distresswhich sometimes

might be delayed distress. This could mean that there are limits

to the kinds of topics about which we interview participants

online or that we restrict our sample to a particular country

or region where we know of psychological services that can

be available to our participants if required.

Given that research into Internet relationships and

sexuality is a relatively new area, future research might also

focus on how to improve ethical practices. For instance,

future studies might interview potential participants about

how they would prefer social scientists to conduct research.

Moreover, gaining a greater understanding of how individuals

perceive private and public space could also influence how

we conduct future studies in this topic area.

concluSIonS

In concluding, while this article has provided examples of

ways forward in our thinking about virtual ethics in respect to

the study of online relationships, it is by no means prescriptive or exhaustive. Rather, it is suggested here that debate

over such issues should be encouraged, and we should avoid

setting standards for how we conduct our Internet research

without also considering the ethical implications of our work.

The way forward is to not restrict the debate amongst social

scientists, but to also consult the individuals we would like

to and are privileged to study.

reFerenceS

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A., & Fitzsimons, G. M.

(2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression

of the true self on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues,

58(1), 33-48.

Buchanan, T., & Smith, J. L. (1999). Using the Internet for

psychological research: Personality testing on the WorldWide Web. British Journal of Psychology, 90(1), 125-144.

2252

Cooper, A., Putnam, D. E., Planchon, L. A., & Boies, S. C.

(1999). Online sexual compulsivity: Getting tangled in the

net. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 6(2), 79-104.

Ess, C., & Jones, S. (2004). Ethical decision-making and

Internet research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics

Working Committee. In E. Buchanan (Ed.), Readings in

virtual research ethics: Issues and controversies (pp. 27-44).

Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Griffiths, M. (2001). Sex on the Internet: Observations

and implications for Internet sex addiction. Journal of Sex

Research, 38(4), 333-342.

Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1995). Love at first byte? Building

personal relationships over computer networks. In J. T. Wood

& S. W. Duck (Eds.), Understudied relationships: Off the

beaten track (pp. 197-233). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mann, C., & Stewart, F. (2000). Internet communication and

qualitative research: A handbook for researching online.

London: Sage Publications.

McCown, J. A., Fischer, D., Page, R., & Homant, M. (2001).

Internet relationships: People who meet people. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 4(5), 593-596.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002).

Relationship formation on the Internet: Whats the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 9-31.

NHMRC. (1999). National statement on ethical conduct

in research involving humans. Retrieved September 25,

2002, from http://www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/

humans/part17.htm

Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002).

E-research: Ethics, security, design, and control in psychological research on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues,

58(1), 161-176.

Parks, M. R., & Floyd, K. (1996). Making friends in cyberspace. Journal of Communication, 46(1), 80-97.

Parks, M. R., & Roberts, L. D. (1998). Making MOOsic:

The development of personal relationships online and a

comparison to their off-line counterparts. Journal of Social

and Personal Relationships, 15(4), 517-537.

Rice, R. E., & Love, G. (1987). Electronic emotion: Socioemotional content in a computer mediated communication

network. Communication Research, 14(1), 85-108.

Schneider, J. P. (2000). Effects of cybersex addiction on the

family: Results of a survey. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7, 31-58.

Slouka, M. (1995). War of the worlds: Cyberspace and the

high-tech assault on reality. New York: Basic Books.

Investigating Internet Relationships

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of

the Internet. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication:

Impersonal, interpersonal and hyperpersonal interaction.

Communication Research, 23(1), 3-43.

Wellman, B. (2004). Connecting communities: On and off

line. Contexts, 3(4), 22-28.

Whitty, M. T. (2002). Liar, liar! An examination of how open,

supportive and honest people are in Chat Rooms. Computers

in Human Behavior, 18(4), 343-352.

Whitty, M. T. (2003a). Pushing the wrong buttons: Mens

and womens attitudes towards online and offline infidelity.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(6), 569-579.

Whitty, M. T. (2003b). Cyber-flirting: Playing at love on the

Internet. Theory and Psychology, 13(3), 339-357.

Whitty, M. T. (2004). Peering into online bedroom windows:

Considering the ethical implications of investigating Internet

relationships and sexuality. In E. Buchanan (Ed.), Readings

in virtual research ethics: Issues and controversies (pp. 203218). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Inc.

Whitty, M. T. (2005). The realness of cyber-cheating: Men

and womens representations of unfaithful Internet relationships. Social Science Computer Review, 23(1), 57-67.

Whitty, M. T. (in press). The art of selling ones self on an

online dating site: The BAR approach. In M. T. Whitty,

A. J. Baker, & J. A. Inman (Eds.), Online matchmaking.

Palgrave Macmillan.

Whitty, M. T., & Carr, A. N. (2003). Cyberspace as potential

space: Considering the Web as a playground to cyber-flirt.

Human Relations, 56(7), 861-891.

Young, K. S., Pistner, M., OMara, J., & Buchanan, J. (1999).

Cyber disorders: The mental health concern for the new millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2(5), 475-479.

key termS

Bebo: A social networking site where members can

communicate with school and university friends, connect

with friends, share photos, comment on others sites and

photos, and write a blog.

Blog: Online diaries on a Web page, where the blogger

updates entries, typically fairly regularly, in reverse chronological sequence.

Chat Room: A Web site, or part of a Web site, that allows individuals to communicate in real time.

Cybersex: Two or more individuals using the Internet

as a medium to engage in discourses about sexual fantasies.

The dialogue is typically accompanied by sexual selfstimulation.

Hot-Chatting: Two or more individuals engaging in

discourses that move beyond light-hearted flirting.

Lurker: A participant in a chat room or a subscriber to

a discussion group, listserv, or mailing list who passively

observes. These individuals typically do not actively partake

in the discussions that befall in these forums.

MUDs and MOOs: Multiple-user dungeons, or more

commonly understood these days to mean multi-user dimension or domains. These were originally a space where

interactive role-playing games could be played, very similar

to Dungeons and Dragons.

Whitty, M. T., & Carr, A. N. (2006). Cyberspace romance:

The psychology of online relationships. Hampshire, UK:

Palgrave Macmillan.

MySpace: A social networking site where members can

communicate with school and university friends, connect

with friends, share photos, comment on others sites and

photos, and write a blog.

Whitty, M., & Gavin, J. (2001). Age/sex/location: Uncovering

the social cues in the development of online relationships.

CyberPsychology and Behavior, 4(5), 623-630.

Online Sexual Activity: Using the Internet for any

sexual activity (e.g., recreation, entertainment, exploitation,

education).

Wysocki, D. K. (1998). Let your fingers to do the talking:

Sex on an adult chat-line. Sexualities, 1(4), 425-452.

Screen Name: A screen name can be an individuals real

name, a variation of an individuals name, or a totally madeup pseudonym. Screen names are especially required on the

Internet for applications such as instant messaging.

Young, K. S., Griffin-Shelley, E., Cooper, A., OMara, J.,

& Buchanan, J. (2000). Online infidelity: A new dimension

in couple relationships with implications for evaluation and

treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7(5), 59-74.

2253

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Somewhere Over The Rainbow Ukulele ChordsDokumen2 halamanSomewhere Over The Rainbow Ukulele Chordsheroedleyenda100% (4)

- First UkuleleDokumen14 halamanFirst Ukuleleadrianomarqs68% (19)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

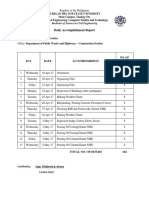

- Daily Accomplishment Report - JANRICKDokumen3 halamanDaily Accomplishment Report - JANRICKJudy Anne BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Best of SQL Server Central Vol 2Dokumen195 halamanBest of SQL Server Central Vol 2madhavareddy29100% (3)

- Basic Electronics Terms and DefinitionsDokumen40 halamanBasic Electronics Terms and DefinitionsIrish Balaba67% (3)

- Awesome OrigamiDokumen17 halamanAwesome OrigamiHaritha100% (6)

- Tiktok Clone ScriptDokumen10 halamanTiktok Clone ScriptWebsenor infotechBelum ada peringkat

- Ukulele Chords For BeginnersDokumen1 halamanUkulele Chords For BeginnersJavierLopezBelum ada peringkat

- ArrowDokumen3 halamanArrowleonardiBelum ada peringkat

- Relevance and Ranking in Online Dating SystemsDokumen8 halamanRelevance and Ranking in Online Dating SystemsTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Ukulele in A Day For DummiesDokumen3 halamanUkulele in A Day For DummiesTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- ArrowDokumen3 halamanArrowleonardiBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Singles - Internet Dating and The Work of FantasyDokumen21 halamanQuality Singles - Internet Dating and The Work of FantasyTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Seahorse OrigamiDokumen8 halamanSeahorse OrigamiTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Whom We Say We Want - Stated and Actual Preferences in Online DatingDokumen1 halamanWhom We Say We Want - Stated and Actual Preferences in Online DatingTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- HVHebrew Verb ConjugationDokumen9 halamanHVHebrew Verb ConjugationTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Mate PreferencesDokumen51 halamanMate PreferencesTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Matching and Sorting in Online DatingDokumen35 halamanMatching and Sorting in Online DatingTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- People Are Experience GoodsDokumen11 halamanPeople Are Experience GoodsDaniel Castro Dos SantosBelum ada peringkat

- First Comes Love, Then Comes Google - An Investigation of Uncertainty Reduction Strategies and Self-Disclosure in Online DatingDokumen32 halamanFirst Comes Love, Then Comes Google - An Investigation of Uncertainty Reduction Strategies and Self-Disclosure in Online DatingTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Value Consensus and Partner Satisfaction Among Dating CouplesDokumen9 halamanValue Consensus and Partner Satisfaction Among Dating CouplesTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Fiore Chi2006 WorkshopRevealing Communication PatternsDokumen4 halamanFiore Chi2006 WorkshopRevealing Communication PatternsTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- The Heart of The MatterDokumen4 halamanThe Heart of The MatterTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Linguistic Properties in Online Dating CommunicationDokumen14 halamanThe Role of Linguistic Properties in Online Dating CommunicationTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Cultural and Media Studies PDFDokumen5 halamanCultural and Media Studies PDFTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Mate PreferencesDokumen37 halamanMate PreferencesTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Online Dating: The Current Status and BeyondDokumen2 halamanOnline Dating: The Current Status and BeyondfredbabaBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Emotionality and Self-Disclosure On Online Dating Versus Traditional DatingDokumen34 halamanThe Impact of Emotionality and Self-Disclosure On Online Dating Versus Traditional DatingTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Relationshopping - Investigating The Market Metaphor in Online DatingDokumen22 halamanRelationshopping - Investigating The Market Metaphor in Online DatingTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Singles - Internet Dating and The Work of FantasyDokumen21 halamanQuality Singles - Internet Dating and The Work of FantasyTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- XXXAndrew - Fiore - Dissertation-Selfpresentation Interpersonal Perception and Partner Selection in Computer-Mediated Relationship FormationDokumen141 halamanXXXAndrew - Fiore - Dissertation-Selfpresentation Interpersonal Perception and Partner Selection in Computer-Mediated Relationship FormationTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Mate Selection Factors in Computer Matched MarriageDokumen5 halamanMate Selection Factors in Computer Matched MarriageTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Lovebirds or Heartbreak - Top Valentine's Day Playlists On FacebookDokumen3 halamanLovebirds or Heartbreak - Top Valentine's Day Playlists On FacebookTionaTionaBelum ada peringkat

- Serial and licence key collection documentDokumen5 halamanSerial and licence key collection documentAnirudhBelum ada peringkat

- PI Raptor300 enDokumen14 halamanPI Raptor300 enmetalmak ltdaBelum ada peringkat

- Validation Based ProtocolDokumen7 halamanValidation Based ProtocolTerimaaBelum ada peringkat

- Deakin Learning Futures AGENDA 2020 Stage 2: Assessment and Learning DesignDokumen6 halamanDeakin Learning Futures AGENDA 2020 Stage 2: Assessment and Learning DesignAmel Abbas Abbas AbbakerBelum ada peringkat

- Mac vs. PCDokumen18 halamanMac vs. PCsleepwlker2410Belum ada peringkat

- SIDBI empanelment guide for architects, consultantsDokumen21 halamanSIDBI empanelment guide for architects, consultantsbethalasBelum ada peringkat

- Capturing Deleted Records of Source in WarehouseCapturing Deleted Records of Source in WarehouseDokumen2 halamanCapturing Deleted Records of Source in WarehouseCapturing Deleted Records of Source in WarehouseAsad HussainBelum ada peringkat

- Drone Ecosystem IndiaDokumen1 halamanDrone Ecosystem IndiaSneha ShendgeBelum ada peringkat

- How To Perform Live Domain Migration On LDOM - Oracle VM SPARC - UnixArenaDokumen1 halamanHow To Perform Live Domain Migration On LDOM - Oracle VM SPARC - UnixArenarasimBelum ada peringkat

- DronesDokumen4 halamanDronespincer-pincerBelum ada peringkat

- Experienced Civil Engineer ResumeDokumen2 halamanExperienced Civil Engineer ResumeAkhilKumarBelum ada peringkat

- OC - Automotive Engine MechanicDokumen5 halamanOC - Automotive Engine MechanicMichael NcubeBelum ada peringkat

- SRM Engineering College attendance sheetDokumen2 halamanSRM Engineering College attendance sheetsachinBelum ada peringkat

- Securing SC Series Storage Best Practices Dell 2016 (BP1082)Dokumen17 halamanSecuring SC Series Storage Best Practices Dell 2016 (BP1082)Le Ngoc ThanhBelum ada peringkat

- Solved ProblemsDokumen24 halamanSolved ProblemsParth Cholera100% (1)

- JWT Service ImplDokumen2 halamanJWT Service ImplscribdBelum ada peringkat

- Incubator 8000 IC / SC / NC Electrical Safety Test in The USA and Canada According To UL2601-1 / Table 19.100 and Table IVDokumen4 halamanIncubator 8000 IC / SC / NC Electrical Safety Test in The USA and Canada According To UL2601-1 / Table 19.100 and Table IVVinicius Belchior da SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- CAST - Ethical Hacking Course OutlineDokumen2 halamanCAST - Ethical Hacking Course Outlinerazu1234Belum ada peringkat

- Stud Finder Final v1Dokumen6 halamanStud Finder Final v1api-323825539Belum ada peringkat

- FM Global Property Loss Prevention Data Sheets: List of FiguresDokumen25 halamanFM Global Property Loss Prevention Data Sheets: List of Figureskw teoBelum ada peringkat

- LJQHelp PaletteDokumen2 halamanLJQHelp PaletteMuhammad AwaisBelum ada peringkat

- GXP Usermanual EnglishDokumen44 halamanGXP Usermanual EnglishKatherine Nicole LinqueoBelum ada peringkat

- Modules English Industrial EngineeringDokumen16 halamanModules English Industrial EngineeringMikel Vega GodoyBelum ada peringkat

- Hellas Sat 4Dokumen1 halamanHellas Sat 4Paolo LobbaBelum ada peringkat

- Hps 21avp EeDokumen1 halamanHps 21avp EeSekoBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 8Dokumen14 halamanUnit 8samer achkarBelum ada peringkat