Spiritual and Religious Beliefs As Risk Factors For The Onset of Major Depression

Diunggah oleh

Alee VerdinDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Spiritual and Religious Beliefs As Risk Factors For The Onset of Major Depression

Diunggah oleh

Alee VerdinHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

PsychologicalMedicine

http://journals.cambridge.org/PSM

AdditionalservicesforPsychologicalMedicine:

Emailalerts:Clickhere

Subscriptions:Clickhere

Commercialreprints:Clickhere

Termsofuse:Clickhere

Spiritualandreligiousbeliefsasriskfactorsfortheonsetofmajor

depression:aninternationalcohortstudy

B.Leurent,I.Nazareth,J.BellnSaameo,M.I.Geerlings,H.Maaroos,S.Saldivia,I.vab,F.TorresGonzlez,M.Xavier

andM.King

PsychologicalMedicine/FirstViewArticle/January2013,pp112

DOI:10.1017/S0033291712003066,Publishedonline:

Linktothisarticle:http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0033291712003066

Howtocitethisarticle:

B.Leurent,I.Nazareth,J.BellnSaameo,M.I.Geerlings,H.Maaroos,S.Saldivia,I.vab,F.TorresGonzlez,M.Xavier

andM.KingSpiritualandreligiousbeliefsasriskfactorsfortheonsetofmajordepression:aninternationalcohortstudy.

PsychologicalMedicine,AvailableonCJOdoi:10.1017/S0033291712003066

RequestPermissions:Clickhere

Downloadedfromhttp://journals.cambridge.org/PSM,IPaddress:128.40.240.4on30Jan2013

Psychological Medicine, Page 1 of 12.

doi:10.1017/S0033291712003066

f Cambridge University Press 2013

O R I G I N A L AR T I C LE

Spiritual and religious beliefs as risk factors for

the onset of major depression: an international

cohort study

B. Leurent1,2, I. Nazareth2, J. Bellon-Saameno3, M.-I. Geerlings4, H. Maaroos5, S. Saldivia6, I. Svab7,

F. Torres-Gonzalez8, M. Xavier9 and M. King1*

1

Mental Health Sciences Unit, Faculty of Brain Sciences, University College London Medical School, UK

Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health, University College London Medical School, UK

3

Department of Preventive Medicine, El Palo Health Centre, Malaga, Spain

4

University Medical Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands

5

Faculty of Medicine, University of Tartu, Estonia

6

Departamento de Psiquiatra y Salud Mental, Universidad de Concepcion, Chile

7

Department of Family Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

8

CIBERSAM-Granada University, Granada, Spain

9

Department of Mental Health, Faculdade Ciencias Medicas, CEDOC, Lisboa, Portugal

2

Background. Several studies have reported weak associations between religious or spiritual belief and psychological

health. However, most have been cross-sectional surveys in the USA, limiting inference about generalizability. An

international longitudinal study of incidence of major depression gave us the opportunity to investigate this

relationship further.

Method. Data were collected in a prospective cohort study of adult general practice attendees across seven countries.

Participants were followed at 6 and 12 months. Spiritual and religious beliefs were assessed using a standardized

questionnaire, and DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression was made using the Composite International Diagnostic

Interview (CIDI). Logistic regression was used to estimate incidence rates and odds ratios (ORs), after multiple

imputation of missing data.

Results. The analyses included 8318 attendees. Of participants reporting a spiritual understanding of life at

baseline, 10.5 % had an episode of depression in the following year compared to 10.3 % of religious participants

and 7.0 % of the secular group (p<0.001). However, the ndings varied signicantly across countries, with

the dierence being signicant only in the UK, where spiritual participants were nearly three times more likely

to experience an episode of depression than the secular group [OR 2.73, 95 % condence interval (CI) 1.594.68].

The strength of belief also had an eect, with participants with strong belief having twice the risk of

participants with weak belief. There was no evidence of religion acting as a buer to prevent depression after

a serious life event.

Conclusions. These results do not support the notion that religious and spiritual life views enhance psychological

well-being.

Received 13 July 2012 ; Revised 19 November 2012 ; Accepted 6 December 2012

Key words : General practice, longitudinal, major depression, religion, spirituality.

Background

Research ndings, most originating from the USA,

have generally reported a positive, albeit weak, relationship between higher levels of religious involvement and better health once other inuences, such as

* Address for correspondence : Professor M. King, Mental Health

Sciences Unit, University College London, Charles Bell House, 6773

Riding House Street, London W1W 7EJ, UK.

(Email : michael.king@ucl.ac.uk)

age, sex and social support, have been taken into account (Koenig et al. 1998, 2001 ; McCullough & Larson,

1999 ; Johnstone et al. 2008). Nevertheless, many other

studies do not nd such an association (Payne et al.

1991 ; Schaefer, 1997 ; Lewis et al. 2000 ; Gartner et al.

2012). There have been at least two meta-analyses of

relevant studies. The rst examined the relationship

between religiosity and psychological adjustment

(Hackney & Sanders, 2003), while excluding studies

measuring a wider concept of spirituality or those

examining the relationship with mental disorders.

B. Leurent et al.

A small positive correlation between religiosity and

psychological status was found (r=0.10, p<0.0001)

when combining all eect sizes from 35 cross-sectional

studies. Seventy-eight negative relationships were

found in the data set of 264 eect sizes. Greater eects

were seen with institutional religiosity than personal

devotion, and with psychological distress rather

than of life satisfaction. The authors concluded that

greater internality of religious belief was associated

with more positive psychological outcomes. A second

meta-analysis of 147 studies (of which 15 were longitudinal) examined associations between religiosity

and/or spirituality and depressive symptoms and/or

depressive disorder (Smith et al. 2003). Religious/

spiritual belief seemed to have a small negative

(x0.096) correlation with depressive symptoms but

the protective eect of belief was stronger on risk

of major depression after signicant life events.

Unfortunately, the authors did not distinguish evidence from longitudinal versus cross-sectional studies

in their analysis.

Numerous cross-sectional studies have been conducted since 2003, including some outside the USA. In

one very large Canadian community health study,

greater participation in worship was associated with

lower odds of psychiatric disorders but people who

placed greater importance on spiritual values had

higher odds of most psychiatric disorders (Baetz et al.

2006). A further cross-sectional study of more than

6000 people in Korea also reported that strong spiritual values were associated with increased rates of

current depressive disorder (Park et al. 2012).

Most of the studies in the meta-analyses described

above (Hackney & Sanders, 2003 ; Smith et al. 2003)

were cross-sectional in nature and thus we need more

prospective research in a variety of cultures and societies. Recent prospective studies have been small

scale but generally positive in their ndings. Kasen

et al. (2012) and Miller et al. (2012) reported data on 114

adults who were the grown-up children of a cohort of

people at high risk of depression, and matched controls, enrolled in a multi-generational 10-year longitudinal study. Participants for whom religion or

spirituality was highly important seemed to be protected from major depression, especially relapse in

those with a history of depression (Miller et al. 2012).

Religion was also more protective in participants

exposed to negative life events (Kasen et al. 2012).

However, there were few participants, the sample

was very specic (catholic or protestant Caucasians,

who were ospring of depressed parents for the exposed cohort) and ndings were of borderline signicance.

In earlier cross-sectional work in a large sample of

people from a range of ethnic groups in England and

Wales, we reported that holding a spiritual life view

without religious aliation was associated with a

higher prevalence of anxiety and depression (King

et al. 2006a). However, the direction of this association

was unclear. Lack of religion may lead to common

mental disorders in vulnerable people who seek

meaning in their lives. Conversely, people developing

a common mental disorder who are not aliated

to any religious group may become involved in a

search for meaning for relief from symptoms. The

New Age movements and other non-traditional faiths

in Western Europe may reect a search for meaning in

societies such as the UK, where religious practice has

declined steeply in recent decades. We previously

undertook a prospective study to develop a risk prediction algorithm for the onset of major depression in

general practice attendees in seven countries : six

European and one Latin American (King et al. 2008).

These data provided an opportunity to examine the

impact of spiritual and religious beliefs on the development of depression. Our aims were to : (1) examine

the impact of a religious or spiritual life view on

onset of major depression over 12 months ; (2) assess

whether this impact varied for rst or recurrent

episodes of depression ; (3) examine how the impact

varied by religious denomination, change in life

view and change in strength of belief over the

12 months ; and (4) determine whether the form of life

view mediated the impact of signicant life events on

onset of major depression. Our principal hypothesis

was that people expressing a spiritual life view in the

absence of religious aliation or practice are more

likely to develop DSM-IV major depression than those

who have a religious life view or are secular in outlook.

Method

Study setting and design

The study, described in detail elsewhere (King et al.

2006b, 2008), was approved by research ethics committees in each country. It was a prospective cohort

study conducted in (1) 25 general practices in the

Medical Research Council (MRC) General Practice

Research Framework (GPRF) in the UK ; (2) nine large

primary care centres in Andaluca, Spain ; (3) 74 general practices nationwide in Slovenia ; (4) 23 general

practices nationwide in Estonia ; (5) seven large general practice centres near Utrecht, The Netherlands ;

(6) two large primary care centres in the Lisbon area of

Portugal ; and (7) 78 general practices in Concepcion

and Talcahuano in the Eighth Region of Chile. General

practices covered urban and rural populations with

considerable socio-economic variation.

Spiritual and religious beliefs and psychological well-being

Study participants

Consecutive attendees aged 1875 years were recruited in Europe between April 2003 and September

2004 and in Chile between October 2003 and February

2005. Exclusion criteria were inability to understand

the countrys main language, psychosis, dementia and

incapacitating physical illness. Recruitment varied

slightly because of local service dierences. In the UK

and The Netherlands, researchers spoke to patients

while they waited in the practices. In the remaining

European countries, general practitioners (GPs) introduced the study before contact with researchers. In

Chile, attendees were stratied on age and gender on

the basis of local gures and participants were selected

randomly within each stratum. Participants gave informed consent and undertook a research evaluation

within 2 weeks. Only attenders without a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder at baseline were

part of this analysis.

Assessments at baseline

Each instrument or question not available in the relevant languages was translated from English and

back-translated by professional translators (King et al.

2006b).

Demography

We collected standard information on participants

sex, age, education, marital status, employment and

ethnicity.

Religious and spiritual beliefs

The self-report version of the Royal Free Interview

for Spiritual and Religious Beliefs (King et al. 2001)

examines religious aliation and practice, and spiritual beliefs whether or not in the context of religion. In

this study only the rst three items of the questionnaire were used. Before the questions are posed the

respondent reads an introductory statement : In using

the word religion, we mean the actual practice of a

faith, e.g. going to a temple, mosque, church or synagogue. Some people do not follow a religion but do

have spiritual beliefs or experiences. For example, they

believe that there is some power or force other than

themselves, which might inuence their life. Some

people think of this as God or gods, others do not.

Some people make sense of their lives without any

religious or spiritual belief . On the basis of this statement, respondents were asked to indicate whether

their understanding of life was primarily religious,

spiritual, or neither religious nor spiritual (this latter

category will be referred to as secular ). If religious or

spiritual they were then asked to indicate whether

they regarded themselves as having a specic religion.

People with a spiritual life view may identify themselves with a religion, even if they do not practice it.

Finally, religious and spiritual participants were asked

to indicate on scale from 1 to 6 how strongly they held

their life view.

Diagnosis of depression

A DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression in the preceding 6 months was made using the Depression

Section of the Composite International Diagnostic

Interview (CIDI ; Robins et al. 1988 ; WHO, 1997).

Screen for lifetime history of depression

Lifetime depression was considered possible if the respondent answered armatively to both of the rst

two questions of the CIDI Depression Section (WHO,

1997).

Life events

The List of Threatening Experiences questionnaire

(Brugha et al. 1985) enquired about major life events in

the preceding 6 months.

Social support

Adequacy of support from family and friends was

measured using brief standardized questions (Blaxter,

1990).

Follow-up assessments at 6 and 12 months

All participants were re-evaluated for DSM-IV major

depression after 6 and 12 months. At 6 months they

also completed the Royal Free Interview for Spiritual

and Religious Beliefs and the questions on life events.

Statistical analysis

To manage missing data we undertook multiple imputation by chained equation, using the ice procedure

in Stata (Royston, 2005). We generated two imputed

databases each containing 30 imputed versions using

all relevant variables predicting depression or missingness ; one database was used for the analysis of the

understanding of life and the other for the analysis of

religious denomination and strength of belief in religious or spiritual participants. Regression results

were combined using Rubins rule (mim command

in Stata). We explored the pattern of missing data

and performed sensitivity analyses on complete cases.

t tests and x2 tests were used to compare groups at

baseline. Incidence rates of major depression were

B. Leurent et al.

obtained on imputed data by univariable logistic regression and presented graphically. Odds ratios (ORs)

unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, social support, past history of depression

and country were computed using logistic regression.

Interactions between the predictor and each covariate

were tested and the model was stratied if an interaction was found. In view of multiple testing, we

considered an interaction signicant at the level of

p<0.01. All other p values reported are two-sided, and

considered signicant at the level of p<0.05. Incidence

rates and ORs are reported along with their 95 % condence intervals (CIs). Standard errors are based on

robust sandwich estimates to account for the clustering eect of each general practice (Huber, 1967).

For the analyses on imputed data, the exact number

of participants in each category of the exposure

variables cannot be reported as it varied slightly

with each imputation. In the presence of missing

data, CIs are a more reliable guide to the precision

around estimates than estimated frequencies. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Release 11

(Stata Corp, 2009).

Results

Response rates and prevalence of DSM-IV major

depression at recruitment

Response to recruitment was high in Portugal (76 %),

Estonia (80 %), Slovenia (80 %) and Chile (97 %) but

lower in the UK (44 %) and The Netherlands (45 %).

Ethical constraints did not allow collection of data on

non-responders at baseline. Across all countries the

response to follow-up at 6 months was at 89.5 %. A

total of 10045 people took part : 219 were excluded on

grounds of age, 143 had a missing CIDI diagnosis

and ve a missing practice identication at baseline.

Of the remaining 9678, 8318 without DSM-IV major

depression (86 %) at baseline were analysed. The median age was 49 years, two-thirds were women,

and 75 % of participants held a religious or spiritual

understanding of life. Women were more likely

than men to have a religious or spiritual understanding of life, and a past history of depression was least

common in people with a spiritual understanding

(Table 1). The characteristics of participants by country are reported in Supplementary Table S1 (available

online). Eleven per cent of participants did not complete the 6-month follow-up and 16 % did not complete the 12-month follow-up. Non-completers tended

to be younger and less educated and had experienced

more serious life events in the 6 months before baseline.

Understanding of life and onset of DSM-IV major

depression over 12 months

Of participants reporting a religious understanding of

life, 10.3 % experienced an episode of major depression

over the subsequent 12 months, compared to 10.5 % of

participants with a spiritual life view and 7.0 % of the

secular group (p<0.001). This nding was examined

more closely in a logistic regression with secular

participants as the reference group. The results are

reported unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, social support, past history of

depression and country. Participants with a spiritual

understanding of life had a greater risk of major depression at 6 or 12 months than participants with

neither a spiritual nor a religious life view (Table 2).

Participants holding a religious understanding of life

were also more at risk than secular participants, but

this nding lost statistical signicance after adjustment. When stratied by country, however, our nding that a spiritual life view predisposed people to

major depression was signicant only in the UK,

where spiritual participants were nearly three times

more likely to experience an episode of depression

than the secular group (OR 2.73, 95 % CI 1.594.68)

(Table 2). In a post-hoc analysis, using international

surveys (European Values Study, 2012 ; World Values

Survey, 2012) we ranked the countries on the proportion of people considering themselves religious

(from least to most : the UK, Estonia, The Netherlands,

Spain, Chile, Slovenia, Portugal). The variation in results between countries was not explained by the importance of religion in each country (results available

from the authors on request).

Understanding of life and onset of rst episode or

recurrence of major depression over 12 months

To investigate the eect of religion on rst episode

versus recurrence of depression, we stratied the

analysis by lifetime history of depression. The eect of

a religious versus a secular understanding of life

was similar in predicting new onset (OR 1.60, 95 % CI

1.052.42) and recurrence (OR 1.44, 95 % CI 1.071.93).

A spiritual view of life did not predict onset of depression in participants with no history of depression

(OR 1.04, 95 % CI 0.631.73) but was related to new

occurrence for participants with a past history of depression (OR 1.61, 95 % CI 1.192.17). However, this

interaction was not signicant (p=0.15).

Religious denomination and onset of major

depression

In the 6094 participants with a spiritual or religious

understanding of life, the incidence of major

Spiritual and religious beliefs and psychological well-being

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and understanding of life

Understanding of life

Religious

(n=4348, 52 %)

Country, n ( %)

UK

Spain

Slovenia

Estonia

The Netherlands

Portugal

Chile

Gender, n ( %)

Female

Male

Age (years), n ( %)

1829

3039

4049

5059

6069

7076

Married/living with partner, n ( %)

No

Yes

Missing

Education, n ( %)

Above school

Secondary

Primary/no education

Trade/other

Missing

Employment, n ( %)

Employed/student

Retired

Unemployed/other

Missing

European ethnicity, n ( %)

No

Yes

Missing

Past history of depression, n ( %)

No

Yes

Missing

Family and friends support

Mean (S.D.)

Missing

Religious denomination, n ( %)

Catholic

Protestant

Other religion

No specic religion

Missing

Strength of belief

Mean (S.D.)

Missing

S.D.,

a

Spiritual

(n=1746, 21 %)

Neither

(n=2087, 25 %)

Totala

(n=8318)

p valueb

462 (10.6)

714 (16.4)

322 (7.4)

189 (4.3)

358 (8.2)

833 (19.2)

1470 (33.8)

300 (17.2)

136 (7.8)

328 (18.8)

227 (13.0)

143 (8.2)

75 (4.3)

537 (30.8)

354 (17.0)

153 (7.3)

387 (18.5)

506 (24.2)

469 (22.5)

97 (4.6)

121 (5.8)

1131 (13.6)

1006 (12.1)

1048 (12.6)

923 (11.1)

1077 (12.9)

1005 (12.1)

2128 (25.6)

<0.001

3045 (70.0)

1303 (30.0)

1235 (70.7)

511 (29.3)

1235 (59.2)

852 (40.8)

5599 (67.3)

2719 (32.7)

<0.001

498 (11.5)

585 (13.5)

764 (17.6)

946 (21.8)

1022 (23.5)

533 (12.3)

332 (19.0)

356 (20.4)

356 (20.4)

333 (19.1)

266 (15.2)

103 (5.9)

406 (19.5)

429 (20.6)

398 (19.1)

435 (20.8)

293 (14.0)

126 (6.0)

1244 (15.0)

1380 (16.6)

1540 (18.5)

1745 (21.0)

1619 (19.5)

790 (9.5)

<0.001

1333 (30.7)

3005 (69.3)

10

615 (35.3)

1129 (64.7)

2

634 (30.5)

1445 (69.5)

8

2614 (31.5)

5681 (68.5)

23

0.001

656 (15.1)

1324 (30.5)

2011 (46.3)

349 (8.0)

8

533 (30.5)

627 (35.9)

388 (22.2)

197 (11.3)

1

749 (36.0)

820 (39.4)

343 (16.5)

167 (8.0)

8

1965 (23.7)

2844 (34.3)

2769 (33.4)

718 (8.7)

22

<0.001

1663 (38.4)

1017 (23.5)

1654 (38.2)

14

975 (56.1)

276 (15.9)

487 (28.0)

8

1313 (63.5)

336 (16.2)

420 (20.3)

18

4003 (48.4)

1662 (20.1)

2610 (31.5)

43

<0.001

1535 (35.4)

2806 (64.6)

7

563 (32.3)

1180 (67.7)

3

162 (7.8)

1921 (92.2)

4

2265 (27.3)

6039 (72.7)

14

<0.001

2021 (46.5)

2322 (53.5)

5

728 (41.8)

1015 (58.2)

3

1039 (49.9)

1046 (50.2)

2

3863 (46.5)

4445 (53.5)

10

<0.001

12.7 (2.4)

34

12.3 (2.7)

10

12 (2.7)

19

12.4 (2.5)

77

<0.001

2680 (62.2)

1248 (29.0)

243 (5.6)

137 (3.2)

40

563 (33.0)

317 (18.6)

118 (6.9)

708 (41.5)

40

3243 (53.9)

1565 (26.0)

361 (6.0)

845 (14.1)

80

<0.001

4.3 (1.5)

90

3.7 (1.6)

30

4.1(1.6)

120

<0.001

N.A.

N.A.

Standard deviation ; N.A., not applicable.

Including 137 missing understanding of life.

b

p value for dierence between understanding of life, from t tests or x2 tests, as appropriate.

B. Leurent et al.

Table 2. Odds ratios (ORs) for onset of major depression over 12 months by understanding

of life, compared to neither religious nor spiritual

Unadjusted OR (95 % CI)

Adjusted ORa (95 % CI)

Overall

Religious

Spiritual

1.52 (1.191.93)**

1.56 (1.212.02)**

1.14 (0.871.50)

1.32 (1.021.70)*

UK

Religious

Spiritual

1.35 (0.682.68)

2.73 (1.594.68)***

1.86 (0.883.92)

2.68 (1.524.71)**

Spain

Religious

Spiritual

1.41 (0.782.54)

1.53 (0.733.20)

1.34 (0.732.46)

1.50 (0.733.07)

Slovenia

Religious

Spiritual

0.62 (0.261.46)

1.06 (0.522.16)

0.69 (0.271.73)

1.10 (0.522.34)

Estonia

Religious

Spiritual

1.16 (0.632.13)

1.08 (0.591.98)

1.06 (0.512.22)

1.14 (0.622.12)

The Netherlands

Religious

Spiritual

0.63 (0.311.28)

1.15 (0.622.13)

0.69 (0.351.37)

1.07 (0.572.02)

Portugal

Religious

Spiritual

2.40 (0.5510.43)

1.96 (0.3810.05)

1.78 (0.398.08)

1.52 (0.278.48)

Chile

Religious

Spiritual

1.12 (0.582.17)

1.03 (0.532.00)

1.08 (0.542.14)

1.04 (0.561.96)

CI, Condence interval.

Values based on imputed data.

a

Adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, social support, past history of

depression, and country.

* p <0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

depression over the subsequent 12 months was similar

across the dierent religious denominations (Catholic

9.8 %, Protestant 10.9 %, other religion 11.5 %, no specic religion 10.8 %, p=0.65). In a post-hoc analysis

in the 1746 participants who reported a spiritual

understanding of life, a similar incidence of major depression over the subsequent 12 months was found

between those who were able to nominate a religious

aliation and those who were not (10.7 % v. 11.1 %,

p=0.41).

Strength of belief at baseline and onset of major

depression

Higher strength of belief in the 6094 participants

who reported a spiritual or religious life view was associated with a greater likelihood of DSM-IV major

depression over the subsequent 12 months after adjustment for age, sex, education, employment, social

support, past history of depression, and country

(unadjusted OR per unit increase on the scale of

strength of belief 1.14, 95 % CI 1.071.21 ; adjusted OR

1.08, 95 % CI 1.001.15) (Fig. 1). There was no interaction between country and strength of belief (p=0.16).

Those with a strongly held belief were twice as likely

to experience major depression in the subsequent

12 months as those with a weakly held belief.

Change in strength of belief and subsequent onset

of major depression

The incidence rate of depression between 6 and

12 months was 5.5 %. We examined whether change

over the rst 6-month follow-up in the strength of

spiritual or religious belief (strength score at 6 months

minus score at baseline) was associated with onset

of major depression between 6 and 12 months, after

adjustment for strength of belief at baseline and other

Incidence of depression over 12 months (%)

Spiritual and religious beliefs and psychological well-being

16

Incidence

95% CI

14

12.5

12

11.7

10.1

10

9.2

8

7.4

6.2

6

4

2

n*= 520

443

1075

1255

947

1734

Weakly

Strongly

How strongly do you hold your religious or spiritual view of life?

OR and 95%CI for depression at 12 months

Fig. 1. Incidence of major depression versus strength of spiritual or religious belief. Based on imputed data. * Frequencies based

on observed data, not numbers included in analysis. CI, Condence interval.

2.21

2

1.47

1.25

1.00

0.94

0.93

0.92

0.77

0.79

0.5

0.25

n*= 51

5/4

140

328

844

2193

806

405

171

113

0 (Ref.)

+1

+2

+3

+4/+5

Difference in strength of belief between baseline and 6 months

Fig. 2. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for onset of major depression between 6 and 12 months after a change in strength of belief

between baseline and 6 months. OR adjusted for strength of belief at baseline, age, sex, education, employment, social support,

past history of depression, and country. Values based on imputed data. * Frequencies based on observed data, not numbers

included in analysis. CI, Condence interval.

covariates. Those whose belief decreased seemed

to be at greater risk of depression whereas those

whose belief increased had slightly less risk (Fig. 2).

However, CIs were wide, especially for the larger

degrees of change.

Change in the nature of life view and subsequent

onset of major depression

Although an understanding of life (religious, spiritual

or secular) is relatively stable in most people

(King et al. 1999), 27.1 % of participants in this

study changed their life view between baseline and

the 6-month interview. Thus, we examined whether

change in the nature of the life view between

baseline and 6 months had any association with onset

major depression between 6 and 12 months. Point

estimates were in the direction of higher risk of depression for change in a religious direction and

lower risk for change in a secular direction, but the

CIs were wide and no signicant dierence was found

(Table 3).

B. Leurent et al.

Table 3. Odds ratios (ORs) for onset of major depression between 6 and 12 months, after a

change in understanding of life between baseline and 6 months

Understanding of life

At baseline

At 6 months

Frequencya

Unadjusted OR

(95 % CI)

Adjusted ORb

(95 % CI)

Religious

Religious

Spiritual

Neither

3004

658

175

1.00 (Reference)

0.98 (0.621.53)

0.64 (0.261.56)

1.00 (Reference)

0.97 (0.611.55)

0.87 (0.352.16)

Spiritual

Religious

Spiritual

Neither

436

887

253

1.40 (0.842.32)

1.00 (Reference)

1.05 (0.542.03)

1.51 (0.872.61)

1.00 (Reference)

1.09 (0.562.14)

Neither

Religious

Spiritual

Neither

196

265

1413

1.53 (0.703.36)

1.46 (0.722.96)

1.00 (Ref)

1.31 (0.533.19)

1.35 (0.662.78)

1.00 (Ref)

Incidence of depression over 12 months (%)

CI, Condence interval.

Values based on imputed data.

a

Frequencies based on observed data, not numbers included in analysis.

b

Adjusted for age, sex, education, employment, social support, past history of

depression, and country.

20

Religious

Spiritual

Neither

15

10

n* = 3474

0

1749

2235

1

>1

Life events between baseline and 6 months

Fig. 3. Modifying eect of life understanding on major depression after serious life events. Values based on imputed data.

* Frequencies based on observed data, not numbers included in analysis.

Impact of belief on the relationship between serious

life events and onset of major depression

Sensitivity of the analysis to imputation of missing

data

Finally, we examined whether a religious or spiritual

understanding of life modied the risk of major depression following a serious life event. As expected,

the incidence of major depression between baseline

and 12 months was higher for patients who experienced serious life events (Fig. 3). Understanding of

life was not a signicant modifying factor of the

eect of life events on depression (unadjusted p=0.57,

adjusted p=0.48).

When imputed data were compared to the observed

data we found a similar distribution between understanding of life categories, but the incidence of major

depression at 6 or 12 months was higher in the imputed data (8.7 % v. 9.5 %), reecting the higher likelihood of dropping out for patients at risk of depression

at baseline. No major discrepancy was found between

imputed data and complete-case analyses. For example, the OR of developing major depression by 6 or

Spiritual and religious beliefs and psychological well-being

12 months was 1.64 (95 % CI 1.262.15) for people with

a religious understanding and 1.74 (95 % CI 1.342.26)

for people with a spiritual understanding of life,

compared to 1.52 and 1.56 respectively on imputed

data (Table 2).

Discussion

Main ndings

We found that people who held a religious or spiritual

understanding of life had a higher incidence of depression than those with a secular life view. However,

this nding varied by country ; in particular, people in

the UK who had a spiritual understanding of life were

the most vulnerable to the onset of major depression.

Regardless of country, the stronger the spiritual or religious belief at baseline, the higher the risk of onset of

depression. Although our main nding of an association between religious life understanding and onset

of depression varied by country, we found no

evidence that spirituality may protect people, and

only weak evidence that a religious life view was

possibly protective in two countries (Slovenia and The

Netherlands). Finally, there was no moderating eect

of religious and spiritual understanding of life on the

impact of life events on onset of major depression.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of our study are its prospective

cohort design, the involvement of several countries,

the large sample size and the use of standardized assessments of religious/spiritual belief, other risk variables and major depression. However, combining

people from dierent cultures creates heterogeneity

and runs the risk of missing real dierences within

countries. Despite a large sample size, we lacked

power for some of the analyses, particularly the assessment of statistical interactions. However, to our

knowledge there are very few data sets available containing variables on spiritual and religious beliefs that

are large enough to undertake interaction analyses.

Thus we consider it is important to show the results to

avoid a reporting bias that favours statistically signicant results (Dwan et al. 2008). Another strength

of this study is the use of multiple imputation to take

account of participants who dropped out. Assuming

predictors of missingness have been examined at

baseline, this should give unbiased ndings, as opposed to restricting the analysis to participants who

completed both follow-ups only, which may represent

a sample at lesser risk of depression than the original

one. However, participations rates were low in some

countries, and we cannot assume that ndings in

general practice attendees can be generalized to the

whole population. Our study sample is likely to have

a more complex medical history ; for example, 53 %

reported a lifetime history of depression although

other evidence would suggest this gure is usually in

the range 3040 % (Kruijshaar et al. 2005). However,

our population may be more representative of life

views than those who might participate in a study of

religion. The original aim of this study was to develop

a risk prediction algorithm for depression (PredictD ;

King et al. 2008), and thus our analysis is limited to the

religiosity data available. Religion did not appear as a

variable in the nal prediction algorithm PredictD,

which included only the most parsimonious combination of risk factors of depression, but this does

not imply the absence of a relationship between religiosity and depression. Although our questions were

limited to peoples overall view of religion and spirituality, rather than the detail of any specic belief,

they applied to all people and not just those with a

Christian background, which is often the case in North

American research. Another limitation is the diculty

distinguishing religion and spirituality and the trouble

respondents may have in placing themselves in one of

the two categories. This may account for a proportion

of the 27 % of participants who changed their life view

between baseline and 6 months. However, the questions have high repeatability (King et al. 2001) and

clear denitions were given in a short note preceding

the question, ensuring a universal understanding of

the term across the dierent countries and cultures.

Furthermore, they avoided the common pitfall in religion studies of conating questions on religion and

spiritual belief with those on psychological well-being

(Koenig, 2008). Finally, the relationship between

religion, spirituality and mental symptoms should

not necessarily be interpreted as causal in nature.

Although the longitudinal design removes the possibility of reverse causation, unmeasured confounders

in the complex relationship between religiosity and

depression are likely to remain, even after adjustment

for main risk factors of depression.

Relationship to other ndings

Our work adds to a growing body of evidence that

spiritual beliefs in the absence of a clear religious

aliation or practice increase vulnerability to depression (Baetz et al. 2006 ; Braam et al. 2007 ; Park et al.

2012) ; it also contrasts with many studies where religious and spiritual beliefs and practice have been

found to be associated with better mental health.

An explanation for this disparity could be the complex

relationship between the concepts of religiosity

and well-being, and that ndings in any specic

10

B. Leurent et al.

population may not generalize to another. Research in

this eld has been dominated by North American

studies, whereas in the more secular cultures of

Europe, religious people may feel less supported in

their faith. Alternatively, it may relate to the ways in

which such beliefs are measured in research. In their

meta-analysis, Hackney & Sanders (2003) criticized

many studies for measuring religion and spirituality

with insucient depth and suggested that a multifaceted concept such as religious belief and practice

may have complex associations with mental health.

In their meta-analysis of 147 studies on religious

belief and depression, Smith et al. (2003) found that

extrinsic religious orientation and so-called negative

religious coping were associated with higher levels of

depressive symptoms. However, they also reported

that the negative correlation between religiousness

and depressive symptoms was at its greatest in the

presence of life stress and suggested that religion may

have a buering eect on the impact of life events. We

did not nd evidence of such buering. They speculated that social desirability of response (exaggerating

religiousness and downrating depressive symptoms),

or the possibility that religious people might be better

at expressing emotion and thus coping with stress,

might explain some of the correlation in their studies

that were mainly cross-sectional in nature.

Recent longitudinal research suggests that attaching

a high importance to religion was associated with

lower risk of recurrence of depression in the subsequent

10 years (Miller et al. 2012) and had a protective eect

after negative life events (Kasen et al. 2012). We have

not been able to replicate either of these ndings in

this cohort. Our study was, however, consistent with

their nding of no clear relationship between religious

denomination and depression.

The disparity in the ndings suggests that, if there

is an association between religion/spirituality and

psychological well-being, it is likely to be weak. If religious belief has a powerful positive eect on mental

health, we would expect to detect it in most studies.

Implications

Why a religious or spiritual life view might place

people at risk of depression remains unclear. One explanation is that people predisposed to depression at

baseline may seek meaning in spiritual or religious

sources. The possibility that people predisposed to

depression increase their search for existential meaning in religion and spirituality is supported by our

nding that change in belief over time towards greater

religiosity did seem to be related to greater risk of depression.

In conclusion, we found that holding a religious or

spiritual life view, in contrast to a secular outlook,

predisposed people to the onset of major depression

and that such beliefs and practice did not act as a

buer to adverse life events. Our ndings highlight

the complexity of the relationship between religion,

spirituality and mental health and oer a challenge to

an increasing tendency to regard religion and spirituality as being good for mental well-being (Schumann

& Meador, 2003).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper

visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713003066.

Acknowledgements

The study in Europe was funded by a European

Commission Vth Framework grant (PREDICT-QL4CT2002-00683). Funding in Chile was provided by

project FONDEF DO2I-1140. We are grateful for part

support in Europe from : the Estonian Scientic

Foundation (grant 5696) ; the Slovenian Ministry for

Research (grant 4369-1027) ; the Spanish Ministry of

Health (FIS references : PI041980, PI041771, PI042450)

and the Spanish Network of Primary Care Research,

redIAPP (ISCIII-RETIC RD06/0018) and SAMSERAP

group ; and the UK NHS Research and Development

oce for service support costs in the UK. The funders

had no direct role in the design or conduct of the

study, interpretation of the data or review of the

manuscript.

M. King had full access to the data and takes responsibility for their integrity and the accuracy of

the data analysis. We thank all patients and general

practice sta who took part ; the European Oce at

University College London for their administrative

assistance at the coordinating centre ; K. McCarthy,

the projects scientic ocer in the European

Commission, Brussels, for his helpful support and

guidance ; the UK MRC GPRF ; L. Letley from the MRC

GPRF ; the GPs of the Utrecht General Practitioners

Network ; and the Camden and Islington Mental

Health and Social Care Trust. We also acknowledge

the Maristan network, through which the collaboration in Spain, Portugal, the UK and Chile rst developed.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Spiritual and religious beliefs and psychological well-being

References

Baetz M, Bowen R, Jones G, Koru-Sengul T (2006). How

spiritual values and worship attendance relate to

psychiatric disorders in the Canadian population. Canadian

Journal of Psychiatry 51, 654661.

Blaxter M (1990). Health and Lifestyles. Routledge : London.

Braam AW, Deeg DJ, Poppelaars JL, Beekman AT,

van Tilburg W (2007). Prayer and depressive symptoms

in a period of secularization : patterns among older adults

in the Netherlands. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry

15, 273281.

Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J (1985). The

List of Threatening Experiences : a subset of 12 life event

categories with considerable long-term contextual threat.

Psychological Medicine 15, 189194.

Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW,

Cronin E, Decullier E, Easterbrook PJ, Von Elm E,

Gamble C, Ghersi D, Ioannidis JP, Simes J,

Williamson PR (2008). Systematic review of the empirical

evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting

bias. PLoS One 3, e3081.

European Values Study (2012). Research theme : religion

(www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu/evs/research/themes/

religion/). Accessed 6 July 2012.

Gartner J, Larson DB, Allen DG (2012). Religious

commitment and mental health : a review of the empirical

literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology 19, 625.

Hackney CH, Sanders GS (2003). Religiosity and mental

health : a meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the

Scientic Study of Religion 42, 4355.

Huber PJ (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood

estimates under non-standard conditions. Proceedings of the

Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and

Probability 1, 221233.

Johnstone B, Franklin KL, Yoon DP, Burris J, Shigaki C

(2008). Relationships among religiousness, spirituality, and

health for individuals with stroke. Journal of Clinical

Psychology in Medical Settings 15, 308313.

Kasen S, Wickramaratne P, Gamero MJ, Weissman MM

(2012). Religiosity and resilience in persons at high

risk for major depression. Psychological Medicine 42,

509519.

King M, Speck P, Thomas A (1999). The eect of spiritual

beliefs on outcome from illness. Social Science and Medicine

48, 12911299.

King M, Speck P, Thomas A (2001). The Royal Free

Interview for Spiritual and Religious Beliefs : development

and validation of a self-report version. Psychological

Medicine 31, 10151023.

King M, Walker C, Levy G, Bottomley C, Royston P,

Weich S, Bellon-Saameno J, Moreno B, Svab I, Rotar D,

Rifel J, Maaroos H, Aluoja A, Kalda R, Neeleman J,

Geerlings MI, Xavier M, Carraca I, Goncalves-Pereira M,

Vicente B, Saldivia S, Melipillan R, Torres-Gonzalez F,

Nazareth I (2008). Development and validation of

an international risk prediction algorithm for

episodes of major depression in general practice

attendees : the PredictD study. Archives of General

Psychiatry 65, 13681376.

11

King M, Weich S, Nazroo J, Blizard R (2006a).

Religion, mental health and ethnicity. EMPIRIC a

national survey of England. Journal of Mental Health 15,

153162.

King M, Weich S, Torres-Gonzalez F, Svab I, Maaroos HI,

Neeleman J, Xavier M, Morris R, Walker C,

Bellon-Saameno JA, Moreno-Kustner B, Rotar D, Rifel J,

Aluoja A, Kalda R, Geerlings MI, Carraca I,

de Almeida MC, Vicente B, Saldivia S, Rioseco P,

Nazareth I (2006 b). Prediction of depression in European

general practice attendees : the PREDICT study. BMC

Public Health 6, 6.

Koenig HG (2008). Concerns about measuring spirituality

in research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196,

349355.

Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL (1998). Religiosity and

remission of depression in medically ill older patients.

American Journal of Psychiatry 155, 536542.

Koenig HK, McCullough ME, Larson DB (2001).

Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford University Press :

Oxford.

Kruijshaar ME, Barendregt J, Vos T, de Graaf R, Spijker J,

Andrews G (2005). Lifetime prevalence estimates of major

depression : an indirect estimation method and a

quantication of recall bias. European Journal of

Epidemiology 20, 103111.

Lewis CA, Maltby J, Burkinshaw S (2000). Religion and

happiness : still no association. Journal of Beliefs and Values

21, 233236.

McCullough ME, Larson DB (1999). Religion and

depression : a review of the literature. Twin Research 2,

126136.

Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gamero MJ, Sage M,

Tenke CE, Weissman MM (2012). Religiosity and

major depression in adults at high risk : a tenyear prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry

169, 8994.

Park JI, Hong JP, Park S, Cho MJ (2012). The relationship

between religion and mental disorders in a Korean

population. Psychiatry Investigation 9, 2935.

Payne IR, Bergin AE, Bielema KA, Jenkins PH (1991).

Review of religion and mental health : prevention and the

enhancement of psychosocial functioning. Prevention in

Human Services 9, 1149.

Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE,

Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R,

Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH (1988). The

Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in

conjunction with dierent diagnostic systems and

in dierent cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry 45,

10691077.

Royston P (2005). Multiple imputation of missing values :

update of ice. Stata Journal 5, 527536.

Schaefer WE (1997). Religiosity, spirituality, and personal

distress among college students. Journal of College Student

Development 38, 633644.

Schumann JJ, Meador KG (2003). Heal Thyself : Spirituality,

Medicine, and the Distortion of Christianity. Oxford

University Press : New York.

12

B. Leurent et al.

Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J (2003). Religiousness and

depression : evidence for a main eect and the moderating

inuence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 129,

614636.

StataCorp (2009). Stata Statistical Software : Release 11. Stata

Corporation : College Station, TX.

WHO (1997). Composite International Diagnostic

Interview (CIDI). Version 2.1. World Health Organization :

Geneva.

World Values Survey (2012). Online Data Analysis, WVS

20052008 (www.wvsevsdb.com/wvs/

WVSAnalizeStudy.jsp). Accessed 6 July 2012.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Case for Faith Sharing Ancient Secrets for Longer Life, Health and HappinessDari EverandA Case for Faith Sharing Ancient Secrets for Longer Life, Health and HappinessBelum ada peringkat

- 8 The Role of Religion in Buffering The Impact of Stressful Life EventsDokumen13 halaman8 The Role of Religion in Buffering The Impact of Stressful Life Eventsyasewa1995Belum ada peringkat

- Ni Hms 101891 Bienestar y DepresiónDokumen12 halamanNi Hms 101891 Bienestar y DepresiónKaren MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Religion Spirituality and Gender-Diferentiated Trajectories - Kent 2019Dokumen18 halamanReligion Spirituality and Gender-Diferentiated Trajectories - Kent 2019Mércia FiuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Dep Rel 2Dokumen12 halamanDep Rel 2api-316789328Belum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Geriatri Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014Dokumen9 halamanJurnal Geriatri Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014donkeyendutBelum ada peringkat

- Religiosity, Happiness, Health, and Psychopathology in A Probability Sample of Muslim AdolescentsDokumen14 halamanReligiosity, Happiness, Health, and Psychopathology in A Probability Sample of Muslim AdolescentsA MBelum ada peringkat

- Religion and Health: A Synthesis: of Medicine: From Evidence To Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University PressDokumen39 halamanReligion and Health: A Synthesis: of Medicine: From Evidence To Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University PressBruk AmareBelum ada peringkat

- The Link Between Coronavirus, Anxiety, and Religious Beliefs in The United States and United KingdomDokumen20 halamanThe Link Between Coronavirus, Anxiety, and Religious Beliefs in The United States and United KingdomtariqsoasBelum ada peringkat

- Positive Religious Coping andDokumen14 halamanPositive Religious Coping andDINDA PUTRI SAVIRABelum ada peringkat

- Artigo Espiritualidade e DepressãoDokumen3 halamanArtigo Espiritualidade e DepressãomariafernandamedagliaBelum ada peringkat

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokumen7 halamanNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptSapto SutardiBelum ada peringkat

- Gender Differences in Religious PracticesDokumen13 halamanGender Differences in Religious PracticesLorena RodríguezBelum ada peringkat

- Koenig H ReligionDokumen55 halamanKoenig H ReligionEno FilhoBelum ada peringkat

- Schreiber 2011Dokumen13 halamanSchreiber 2011Angelia Adinda AnggonoBelum ada peringkat

- Spirituality, Social Support, and Survival in Hemodialysis PatientsDokumen8 halamanSpirituality, Social Support, and Survival in Hemodialysis PatientsOktaviani FentiBelum ada peringkat

- Religion and Health in Europe: Cultures, Countries, ContextDokumen6 halamanReligion and Health in Europe: Cultures, Countries, ContextIonut MurariuBelum ada peringkat

- An Exploratory Study of Religious Involvement As A Moderator Between Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life Outcomes of Older AdultsDokumen12 halamanAn Exploratory Study of Religious Involvement As A Moderator Between Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life Outcomes of Older AdultsaryaBelum ada peringkat

- Rossroads: Exploring Research On Religion, Spirituality and HealthDokumen5 halamanRossroads: Exploring Research On Religion, Spirituality and HealthEliza DNBelum ada peringkat

- Religious Coping Stress and Depressive Symptoms AmDokumen14 halamanReligious Coping Stress and Depressive Symptoms AmAdina SpanacheBelum ada peringkat

- Wiley, Society For The Scientific Study of Religion Journal For The Scientific Study of ReligionDokumen15 halamanWiley, Society For The Scientific Study of Religion Journal For The Scientific Study of ReligionAditya M.BBelum ada peringkat

- Koenig, R IndexDokumen8 halamanKoenig, R IndexCata SieversonBelum ada peringkat

- Ellison and Levin 1998Dokumen21 halamanEllison and Levin 1998pecescdBelum ada peringkat

- 2007 Spirituality Religion and WilliamsDokumen4 halaman2007 Spirituality Religion and WilliamsRizha KrisnawardhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Powell, Religion, Spirituality, Health, AmPsy, 2003Dokumen17 halamanPowell, Religion, Spirituality, Health, AmPsy, 2003Muresanu Teodora IlincaBelum ada peringkat

- 10.2190@60w7 1661 2623 6042Dokumen19 halaman10.2190@60w7 1661 2623 6042Mèo Con Du HọcBelum ada peringkat

- The Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: Pastoral Psychology May 1997Dokumen14 halamanThe Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: Pastoral Psychology May 1997Alonso Cabrera RodríguezBelum ada peringkat

- Aging and ReligiusDokumen15 halamanAging and ReligiusFelipe Vázquez PalaciosBelum ada peringkat

- Impact Spirituality PDFDokumen40 halamanImpact Spirituality PDFDavid IK100% (1)

- The Revised Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale in A Sample of Attica's InhabitantsDokumen12 halamanThe Revised Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale in A Sample of Attica's InhabitantslathBelum ada peringkat

- 98-Religion and Mental HealthDokumen4 halaman98-Religion and Mental HealthPatricia Toma100% (1)

- The Relationships Between Religion/spirituality and Mental and Physical Health: A ReviewDokumen14 halamanThe Relationships Between Religion/spirituality and Mental and Physical Health: A ReviewRista RiaBelum ada peringkat

- Religious Training and Religiosity in Psychiatry Residency ProgramsDokumen7 halamanReligious Training and Religiosity in Psychiatry Residency Programsbdalcin5512Belum ada peringkat

- 2008 Article 24134Dokumen15 halaman2008 Article 24134MerryMerdekawatiBelum ada peringkat

- 2016 Agli Frecnh PDFDokumen13 halaman2016 Agli Frecnh PDFnermal93Belum ada peringkat

- JPM Hebert 2009Dokumen10 halamanJPM Hebert 2009Oana RusuBelum ada peringkat

- HOPE Questions Spiritual AssessmentDokumen8 halamanHOPE Questions Spiritual Assessmentsalemink100% (2)

- Integrative Cancer Therapies: Religion, Spirituality, and Cancer: The Question of Individual EmpowermentDokumen13 halamanIntegrative Cancer Therapies: Religion, Spirituality, and Cancer: The Question of Individual Empowermentanon_767892047Belum ada peringkat

- Religious Attributions Pertaining To The Causes and Cures of Mental IllnessDokumen15 halamanReligious Attributions Pertaining To The Causes and Cures of Mental IllnessDayana RomeroBelum ada peringkat

- Mediating Effects Coping Spirituality PsychologicalDistressDokumen13 halamanMediating Effects Coping Spirituality PsychologicalDistressGina SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Dolcos 2021Dokumen14 halamanDolcos 2021Dana MunteanBelum ada peringkat

- Spirituality in Psychiatry?: (Letters To The Ed Tor)Dokumen3 halamanSpirituality in Psychiatry?: (Letters To The Ed Tor)elvineBelum ada peringkat

- What Is SpiritualityDokumen4 halamanWhat Is SpiritualityJoseph Rodney de LeonBelum ada peringkat

- The Relationship Between Religiosity and Anxiety PDFDokumen11 halamanThe Relationship Between Religiosity and Anxiety PDFAini Nayara PutriBelum ada peringkat

- Spirituality/ Religiosity What Do We Understand From Spirituality/ Religiosity?Dokumen5 halamanSpirituality/ Religiosity What Do We Understand From Spirituality/ Religiosity?Tahira JabeenBelum ada peringkat

- Relig Self Control BulletinDokumen25 halamanRelig Self Control BulletinmaureenlesBelum ada peringkat

- Clayton-Jones and Haglund - 2016 - The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Person-1Dokumen20 halamanClayton-Jones and Haglund - 2016 - The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Person-1Douglas GyamfiBelum ada peringkat

- Refrrnsi Keterbatasan PeneltianDokumen16 halamanRefrrnsi Keterbatasan PeneltianDimas NugrohoBelum ada peringkat

- THE THERAPEUTIC VALUE OF JesusDokumen15 halamanTHE THERAPEUTIC VALUE OF JesusJosue FamaBelum ada peringkat

- Allowing Spirituality Into The Healing Process: Original ResearchDokumen9 halamanAllowing Spirituality Into The Healing Process: Original ResearchAmanda DavisBelum ada peringkat

- Role of Religion and Spirituality in Mental Health Assessment and Intervention Obere C.M.Dokumen16 halamanRole of Religion and Spirituality in Mental Health Assessment and Intervention Obere C.M.Igwe Solomon100% (1)

- The Extended Bio-Psycho-Social Model: A Few Evidences of Its EffectivenessDokumen3 halamanThe Extended Bio-Psycho-Social Model: A Few Evidences of Its EffectivenessHemant KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Test UploadDokumen12 halamanTest UploadIzzuddin KhalisBelum ada peringkat

- Psicologia DepressãoDokumen6 halamanPsicologia DepressãoderfeeelBelum ada peringkat

- Do Spirituality and Religiousness Differ With Regard To Personality and - Mihaljevic 2016Dokumen8 halamanDo Spirituality and Religiousness Differ With Regard To Personality and - Mihaljevic 2016Mércia FiuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Psy Research Proposal - Religiosty and DepressionDokumen15 halamanPsy Research Proposal - Religiosty and DepressionHadi RazaBelum ada peringkat

- Integration of Religion Into TCC For Geriatric Anxiety - Paukert 2009Dokumen10 halamanIntegration of Religion Into TCC For Geriatric Anxiety - Paukert 2009Mércia FiuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Depresi Cemas Trhadap ReligiusitasDokumen12 halamanDepresi Cemas Trhadap ReligiusitasGhaniRahmaniBelum ada peringkat

- Spirituality and Mental Health Among TheDokumen8 halamanSpirituality and Mental Health Among ThepujakpathakBelum ada peringkat

- Patient Attitudes Concerning The Inclusion of Spirituality Into Addiction TreatmentDokumen8 halamanPatient Attitudes Concerning The Inclusion of Spirituality Into Addiction TreatmentRamiro JaimesBelum ada peringkat

- Trainee's CharacteristicDokumen3 halamanTrainee's CharacteristicRoldan EstibaBelum ada peringkat

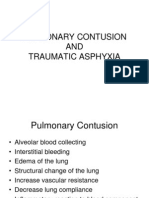

- Lung Contusion & Traumatic AsphyxiaDokumen17 halamanLung Contusion & Traumatic AsphyxiaLady KeshiaBelum ada peringkat

- Pet Registration FormDokumen1 halamanPet Registration FormBRGY MABUHAYBelum ada peringkat

- The Danger of Microwave TechnologyDokumen16 halamanThe Danger of Microwave Technologyrey_hadesBelum ada peringkat

- EnSURE Touch - F&BDokumen6 halamanEnSURE Touch - F&BfaradillafattaBelum ada peringkat

- BISWAS Vol 3, Issue 2Dokumen225 halamanBISWAS Vol 3, Issue 2Vinayak guptaBelum ada peringkat

- Endocrine SystemDokumen41 halamanEndocrine SystemAtteya Mogote AbdullahBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetes: Physical Activity and ExerciseDokumen2 halamanDiabetes: Physical Activity and ExerciseZobaida Khatun JulieBelum ada peringkat

- Antinociceptic Activity of Talisay ExtractDokumen22 halamanAntinociceptic Activity of Talisay ExtractRein Paul Pascua TomasBelum ada peringkat

- Theology of The BodyDokumen2 halamanTheology of The BodyKim JuanBelum ada peringkat

- Your Wellness Profile: Laboratory ActivitiesDokumen4 halamanYour Wellness Profile: Laboratory Activitiesdusty kawiBelum ada peringkat

- Diare Pada BalitaDokumen10 halamanDiare Pada BalitaYudha ArnandaBelum ada peringkat

- Px. Abdomen RadiologiDokumen46 halamanPx. Abdomen RadiologiwagigtnBelum ada peringkat

- Essential DrugsDokumen358 halamanEssential Drugsshahera rosdiBelum ada peringkat

- Glucose KitDokumen2 halamanGlucose KitJuan Enrique Ramón OrellanaBelum ada peringkat

- SRP Batch 1Dokumen32 halamanSRP Batch 1eenahBelum ada peringkat

- Studying in Germany Application Requirements and Processing FeesDokumen4 halamanStudying in Germany Application Requirements and Processing FeesTariro MarumeBelum ada peringkat

- Health & Illness FinalDokumen16 halamanHealth & Illness FinalAJBelum ada peringkat

- Hospital Supply Chain ManagementDokumen39 halamanHospital Supply Chain ManagementFatima Naz0% (1)

- PATHFIT 1 Prelim Lesson 2 and 3Dokumen29 halamanPATHFIT 1 Prelim Lesson 2 and 3hiimleoBelum ada peringkat

- Filipino Research Paper Kabanata 4Dokumen8 halamanFilipino Research Paper Kabanata 4nynodok1pup3100% (1)

- Threats On Child Health and SurvivalDokumen14 halamanThreats On Child Health and SurvivalVikas SamvadBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To Safety Committee Meeting Tech3Dokumen5 halamanA Guide To Safety Committee Meeting Tech3vsrslm100% (1)

- Republic Act No. 11210 - 105-Day Expanded Maternity Leave LawDokumen4 halamanRepublic Act No. 11210 - 105-Day Expanded Maternity Leave LawRaymond CruzinBelum ada peringkat

- Union Carbide Corporation and Others v. Union of India and OthersDokumen73 halamanUnion Carbide Corporation and Others v. Union of India and OthersUrviBelum ada peringkat

- Discrimination in Different FormsDokumen2 halamanDiscrimination in Different FormsPillow ChanBelum ada peringkat

- 70 Questions For The FDA Inspection - Dietary SupplementsDokumen8 halaman70 Questions For The FDA Inspection - Dietary SupplementsSamuel ChewBelum ada peringkat

- MDWF 1030 Carter Plugged Duct Mastitis Abscess PGDokumen5 halamanMDWF 1030 Carter Plugged Duct Mastitis Abscess PGapi-366292665Belum ada peringkat

- Factors Affecting Demand For Soft DrinksDokumen8 halamanFactors Affecting Demand For Soft Drinksخلود البطاحBelum ada peringkat

- Daftar Obat Generik Klinik Citalang Medika Golongan Nama Obat Komposisi Golongan Nama ObatDokumen2 halamanDaftar Obat Generik Klinik Citalang Medika Golongan Nama Obat Komposisi Golongan Nama ObattomiBelum ada peringkat