Persons Part 10

Diunggah oleh

mccm92Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Persons Part 10

Diunggah oleh

mccm92Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

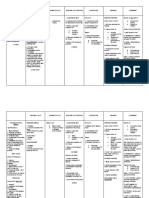

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty.

Vincent Juan) 1

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

PATERNITY and FILIATION

further exchanged reply and rejoinder to buttress their legal

postures.

BADUA v. CA

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 105625 January 24, 1994

MARISSA BENITEZ-BADUA, petitioner,

vs.

COURT OF APPEALS, VICTORIA BENITEZ LIRIO AND

FEODOR BENITEZ AGUILAR, respondents.

Reynaldo M. Alcantara for petitioner.

Augustus Cesar E. Azura for private respondents.

PUNO, J.:

This is a petition for review of the Decision of the 12th

Division of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. No. CV No.

30862 dated May 29, 1992. 1

The facts show that the spouses Vicente Benitez and Isabel

Chipongian owned various properties especially in Laguna.

Isabel died on April 25, 1982. Vicente followed her in the

grave on November 13, 1989. He died intestate.

The fight for administration of Vicente's estate ensued. On

September 24, 1990, private respondents Victoria BenitezLirio and Feodor Benitez Aguilar (Vicente's sister and

nephew, respectively) instituted Sp. Proc. No. 797 (90)

before the RTC of San Pablo City, 4th Judicial Region, Br.

30. They prayed for the issuance of letters of administration

of Vicente's estate in favor of private respondent Aguilar.

They alleged, inter alia, viz.:

xxx xxx xxx

4. The decedent is survived by no other heirs or relatives be

they ascendants or descendants, whether legitimate,

illegitimate or legally adopted; despite claims or

representation to the contrary, petitioners can well and truly

establish, given the chance to do so, that said decedent and

his spouse Isabel Chipongian who pre-deceased him, and

whose estate had earlier been settled extra-judicial, were

without issue and/or without descendants whatsoever, and

that one Marissa Benitez-Badua who was raised and cared

by them since childhood is, in fact, not related to them by

blood, nor legally adopted, and is therefore not a legal

heir; . . .

The trial court then received evidence on the issue of

petitioner's heirship to the estate of the deceased. Petitioner

tried to prove that she is the only legitimate child of the

spouses Vicente Benitez and Isabel Chipongian. She

submitted documentary evidence, among others: (1) her

Certificate of Live Birth (Exh. 3); (2) Baptismal Certificate

(Exh. 4); (3) Income Tax Returns and Information Sheet for

Membership with the GSIS of the late Vicente naming her as

his daughter (Exhs. 10 to 21); and (4) School Records (Exhs.

5 & 6). She also testified that the said spouses reared an

continuously treated her as their legitimate daughter. On the

other hand, private respondents tried to prove, mostly thru

testimonial evidence, that the said spouses failed to beget a

child during their marriage; that the late Isabel, then thirty six

(36) years of age, was even referred to Dr. Constantino

Manahan, a noted obstetrician-gynecologist, for treatment.

Their primary witness, Victoria Benitez-Lirio, elder sister of

the late Vicente, then 77 years of age, 2 categorically

declared that petitioner was not the biological child of the

said spouses who were unable to physically procreate.

On December 17, 1990, the trial court decided in favor of the

petitioner. It dismissed the private respondents petition for

letters and administration and declared petitioner as the

legitimate daughter and sole heir of the spouses Vicente O.

Benitez and Isabel Chipongian. The trial court relied on

Articles 166 and 170 of the Family Code.

On appeal, however, the Decision of the trial court was

reversed on May 29, 1992 by the 17th Division of the Court

of Appeals. The dispositive portion of the Decision of the

appellate court states:

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from herein is

REVERSED and another one entered declaring that

appellee Marissa Benitez is not the biological daughter or

child by nature of the spouse Vicente O. Benitez and Isabel

Chipongian and, therefore, not a legal heir of the deceased

Vicente O. Benitez. Her opposition to the petition for the

appointment of an administrator of the intestate of the

deceased Vicente O. Benitez is, consequently, DENIED; said

petition and the proceedings already conducted therein

reinstated; and the lower court is directed to proceed with the

hearing of Special proceeding No. SP-797 (90) in

accordance with law and the Rules.

Costs against appellee.

SO ORDERED.

In juxtaposition, the appellate court held that the trial court

erred in applying Articles 166 and 170 of the Family Code.

In this petition for review, petitioner contends:

On November 2, 1990, petitioner opposed the petition. She

alleged that she is the sole heir of the deceased Vicente

Benitez and capable of administering his estate. The parties

1. The Honorable Court of Appeals committed error of law

and misapprehension of facts when it failed to apply the

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 2

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

provisions, more particularly, Arts. 164, 166, 170 and 171 of

the Family Code in this case and in adopting and upholding

private respondent's theory that the instant case does not

involve an action to impugn the legitimacy of a child;

3) That in case of children conceived through artificial

insemination, the written authorization or ratification of either

parent was obtained through mistake, fraud, violence,

intimidation, or undue influence.

2. Assuming arguendo that private respondents can question

or impugn directly or indirectly, the legitimacy of Marissa's

birth, still the respondent appellate Court committed grave

abuse of discretion when it gave more weight to the

testimonial evidence of witnesses of private respondents

whose credibility and demeanor have not convinced the trial

court of the truth and sincerity thereof, than the documentary

and testimonial evidence of the now petitioner Marissa

Benitez-Badua;

Art. 170. The action to impugn the legitimacy of the child

shall be brought within one year from the knowledge of the

birth or its recording in the civil register, if the husband or, in

a proper case, any of his heirs, should reside in the city or

municipality where the birth took place or was recorded.

3. The Honorable Court of Appeals has decided the case in a

way not in accord with law or with applicable decisions of the

supreme Court, more particularly, on prescription or laches.

If the husband or, in his default, all of his heirs do not reside

at the place of birth as defined in the first paragraph or where

it was recorded, the period shall be two years if they should

reside in the Philippines; and three years if abroad. If the

birth of the child has been concealed from or was unknown

to the husband or his heirs, the period shall be counted from

the discovery or knowledge of the birth of the child or of the

fact of registration of said birth, which ever is earlier.

We find no merit to the petition.

Petitioner's insistence on the applicability of Articles 164,

166, 170 and 171 of the Family Code to the case at bench

cannot be sustained. These articles provide:

Art. 164. Children conceived or born during the marriage of

the parents are legitimate.

Children conceived as a result of artificial insemination of the

wife with sperm of the husband or that of a donor or both are

likewise legitimate children of the husband and his wife,

provided, that both of them authorized or ratified such

insemination in a written instrument executed and signed by

them before the birth of the child. The instrument shall be

recorded in the civil registry together with the birth certificate

of the child.

Art. 166. Legitimacy of child may be impugned only on the

following grounds:

1) That it was physically impossible for the husband to have

sexual intercourse with his wife within the first 120 days of

the 300 days which immediately preceded the birth of the

child because of:

a) the physical incapacity of the husband to have sexual

intercourse with his wife;

b) the fact that the husband and wife were living separately

in such a way that sexual intercourse was not possible; or

c) serious illness of the husband, which absolutely prevented

sexual intercourse.

2) That it is proved that for biological or other scientific

reasons, the child could not have been that of the husband

except in the instance provided in the second paragraph of

Article 164; or

Art. 171. The heirs of the husband may impugn the filiation of

the child within the period prescribed in the preceding Article

only in the following case:

1) If the husband should die before the expiration of the

period fixed for bringing his action;

2) If he should die after the filing of the complaint, without

having desisted therefrom; or

3) If the child was born after the death of the husband.

A careful reading of the above articles will show that they do

not contemplate a situation, like in the instant case, where a

child is alleged not to be the child of nature or biological child

of a certain couple. Rather, these articles govern a situation

where a husband (or his heirs) denies as his own a child of

his wife. Thus, under Article 166, it is the husband who can

impugn the legitimacy of said child by proving: (1) it was

physically impossible for him to have sexual intercourse, with

his wife within the first 120 days of the 300 days which

immediately preceded the birth of the child; (2) that for

biological or other scientific reasons, the child could not have

been his child; (3) that in case of children conceived through

artificial insemination, the written authorization or ratification

by either parent was obtained through mistake, fraud,

violence, intimidation or undue influence. Articles 170 and

171 reinforce this reading as they speak of the prescriptive

period within which the husband or any of his heirs should

file the action impugning the legitimacy of said child.

Doubtless then, the appellate court did not err when it

refused to apply these articles to the case at bench. For the

case at bench is not one where the heirs of the late Vicente

are contending that petitioner is not his child by Isabel.

Rather, their clear submission is that petitioner was not born

to Vicente and Isabel. Our ruling in Cabatbat-Lim

vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, 166 SCRA 451, 457 cited

in the impugned decision is apropos, viz.:

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 3

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

Petitioners' recourse to Article 263 of the New Civil Code

[now Article 170 of the Family Code] is not well-taken. This

legal provision refers to an action to impugn legitimacy. It is

inapplicable to this case because this is not an action to

impugn the legitimacy of a child, but an action of the private

respondents to claim their inheritance as legal heirs of their

childless deceased aunt. They do not claim that petitioner

Violeta Cabatbat Lim is an illegitimate child of the deceased,

but that she is not the decedent's child at all. Being neither

legally adopted child, nor an acknowledged natural child, nor

a child by legal fiction of Esperanza Cabatbat, Violeta is not

a legal heir of the deceased.

We now come to the factual finding of the appellate court

that petitioner was not the biological child or child of nature

of the spouses Vicente Benitez and Isabel Chipongian. The

appellate court exhaustively dissected the evidence of the

parties as follows:

. . . And on this issue, we are constrained to say that

appellee's evidence is utterly insufficient to establish her

biological and blood kinship with the aforesaid spouses,

while the evidence on record is strong and convincing that

she is not, but that said couple being childless and desirous

as they were of having a child, the late Vicente O. Benitez

took Marissa from somewhere while still a baby, and without

he and his wife's legally adopting her treated, cared for,

reared, considered, and loved her as their own true child,

giving her the status as not so, such that she herself had

believed that she was really their daughter and entitled to

inherit from them as such.

The strong and convincing evidence referred to us are the

following:

First, the evidence is very cogent and clear that Isabel

Chipongian never became pregnant and, therefore, never

delivered a child. Isabel's own only brother and sibling, Dr.

Lino Chipongian, admitted that his sister had already been

married for ten years and was already about 36 years old

and still she has not begotten or still could not bear a child,

so that he even had to refer her to the late Dr. Constantino

Manahan, a well-known and eminent obstetriciangynecologist and the OB of his mother and wife, who treated

his sister for a number of years. There is likewise the

testimony of the elder sister of the deceased Vicente O.

Benitez, Victoria Benitez Lirio, who then, being a teacher,

helped him (he being the only boy and the youngest of the

children of their widowed mother) through law school, and

whom Vicente and his wife highly respected and consulted

on family matters, that her brother Vicente and his wife

Isabel being childless, they wanted to adopt her youngest

daughter and when she refused, they looked for a baby to

adopt elsewhere, that Vicente found two baby boys but

Isabel wanted a baby girl as she feared a boy might grow up

unruly and uncontrollable, and that Vicente finally brought

home a baby girl and told his elder sister Victoria he would

register the baby as his and his wife's child. Victoria Benitez

Lirio was already 77 years old and too weak to travel and

come to court in San Pablo City, so that the taking of her

testimony by the presiding judge of the lower court had to be

held at her residence in Paraaque, MM. Considering, her

advanced age and weak physical condition at the time she

testified in this case, Victoria Benitez Lirio's testimony is

highly trustworthy and credible, for as one who may be

called by her Creator at any time, she would hardly be

interested in material things anymore and can be expected

not to lie, especially under her oath as a witness. There were

also several disinterested neighbors of the couple Vicente O.

Benitez and Isabel Chipongian in Nagcarlan, Laguna (Sergio

Fule, Cecilia Coronado, and Benjamin C. Asendido) who

testified in this case and declared that they used to see

Isabel almost everyday especially as she had drugstore in

the ground floor of her house, but they never saw her to

have been pregnant, in 1954 (the year appellee Marissa

Benitez was allegedly born, according to her birth certificate

Exh. "3") or at any time at all, and that it is also true with the

rest of their townmates. Ressureccion A. Tuico, Isabel

Chipongian's personal beautician who used to set her hair

once a week at her (Isabel's) residence, likewise declared

that she did not see Isabel ever become pregnant, that she

knows that Isabel never delivered a baby, and that when she

saw the baby Marissa in her crib one day she went to

Isabel's house to set the latter's hair, she was surprised and

asked the latter where the baby came from, and "she told me

that the child was brought by Atty. Benitez and told me not to

tell about it" (p. 10, tsn, Nov. 29, 1990).

The facts of a woman's becoming pregnant and growing big

with child, as well as her delivering a baby, are matters that

cannot be hidden from the public eye, and so is the fact that

a woman never became pregnant and could not have,

therefore, delivered a baby at all. Hence, if she is suddenly

seen mothering and caring for a baby as if it were her own,

especially at the rather late age of 36 (the age of Isabel

Chipongian when appellee Marissa Benitez was allegedly

born), we can be sure that she is not the true mother of that

baby.

Second, appellee's birth certificate Exh. "3" with the late

Vicente O. Benitez appearing as the informant, is highly

questionable and suspicious. For if Vicente's wife Isabel,

who wads already 36 years old at the time of the child's

supposed birth, was truly the mother of that child, as

reported by Vicente in her birth certificate, should the child

not have been born in a hospital under the experienced,

skillful and caring hands of Isabel's obstetrician-gynecologist

Dr. Constantino Manahan, since delivery of a child at that

late age by Isabel would have been difficult and quite risky to

her health and even life? How come, then, that as appearing

in appellee's birth certificate, Marissa was supposedly born

at the Benitez home in Avenida Rizal, Nagcarlan, Laguna,

with no physician or even a midwife attending?

At this juncture, it might be meet to mention that it has

become a practice in recent times for people who want to

avoid the expense and trouble of a judicial adoption to simply

register the child as their supposed child in the civil registry.

Perhaps Atty. Benitez, though a lawyer himself, thought that

he could avoid the trouble if not the expense of adopting the

child Marissa through court proceedings by merely putting

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 4

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

himself and his wife as the parents of the child in her birth

certificate. Or perhaps he had intended to legally adopt the

child when she grew a little older but did not come around

doing so either because he was too busy or for some other

reason. But definitely, the mere registration of a child in his or

her birth certificate as the child of the supposed parents is

not a valid adoption, does not confer upon the child the

status of an adopted child and the legal rights of such child,

and even amounts of simulation of the child's birth or

falsification of his or her birth certificate, which is a public

document.

Third, if appellee Marissa Benitez is truly the real, biological

daughter of the late Vicente O. Benitez and his wife Isabel

Chipongian, why did he and Isabel's only brother and sibling

Dr. Nilo Chipongian, after Isabel's death on April 25, 1982,

state

in

the

extrajudicial

settlement

Exh. "E" that they executed her estate, "that we are the sole

heirs of the deceased ISABEL CHIPONGIAN because she

died without descendants or ascendants?" Dr. Chipongian,

placed on a witness stand by appellants, testified that it was

his brother-in-law Atty. Vicente O. Benitez who prepared said

document and that he signed the same only because the

latter told him to do so (p. 24, tsn, Nov. 22, 1990). But why

would Atty. Benitez make such a statement in said

document, unless appellee Marissa Benitez is not really his

and his wife's daughter and descendant and, therefore, not

his deceased wife's legal heir? As for Dr. Chipongian, he

lamely explained that he signed said document without

understanding completely the meaning of the words

"descendant and ascendant" (p. 21, tsn, Nov. 22, 1990). This

we cannot believe, Dr. Chipongian being a practicing

pediatrician who has even gone to the United States (p. 52,

tsn,

Dec.

13,

1990).

Obviously,

Dr. Chipongian was just trying to protect the interests of

appellee, the foster-daughter of his deceased sister and

brother-in-law, as against those of the latter's collateral blood

relatives.

Fourth, it is likewise odd and strange, if appellee Marissa

Benitez is really the daughter and only legal heir of the

spouses Vicente O. Benitez and Isabel Chipongian, that the

latter, before her death, would write a note to her husband

and Marissa stating that:

even without any legal papers, I wish that my husband and

my child or only daughter will inherit what is legally my own

property, in case I die without a will,

and in the same handwritten note, she even implored her

husband

that any inheritance due him from my property when he

die to make our own daughter his sole heir. This do [sic]

not mean what he legally owns or his inherited property. I

leave him to decide for himself regarding those.

(Exhs. "F-1", "F-1-A" and "F-1-B")

We say odd and strange, for if Marissa Benitez is really the

daughter of the spouses Vicente O. Benitez and Isabel

Chipongian, it would not have been necessary for Isabel to

write and plead for the foregoing requests to her husband,

since Marissa would be their legal heir by operation of law.

Obviously, Isabel Chipongian had to implore and supplicate

her husband to give appellee although without any legal

papers her properties when she dies, and likewise for her

husband to give Marissa the properties that he would inherit

from her (Isabel), since she well knew that Marissa is not

truly their daughter and could not be their legal heir unless

her (Isabel's) husband makes her so.

Finally, the deceased Vicente O. Benitez' elder sister Victoria

Benitez Lirio even testified that her brother Vicente gave the

date

December 8 as Marissa's birthday in her birth certificate

because that date is the birthday of their (Victoria and

Vicente's) mother. It is indeed too much of a coincidence for

the child Marissa and the mother of Vicente and Victoria to

have the same birthday unless it is true, as Victoria testified,

that Marissa was only registered by Vicente as his and his

wife's child and that they gave her the birth date of Vicente's

mother.

We sustain these findings as they are not unsupported by

the evidence on record. The weight of these findings was not

negated by documentary evidence presented by the

petitioner, the most notable of which is her Certificate of Live

Birth (Exh. "3") purportedly showing that her parents were

the

late

Vicente Benitez and Isabel Chipongian. This Certificate

registered on December 28, 1954 appears to have been

signed by the deceased Vicente Benitez. Under Article 410

of the New Civil Code, however, "the books making up the

Civil Registry and all documents relating thereto shall be

considered public documents and shall be prima

facieevidence of the facts therein stated." As related above,

the totality of contrary evidence, presented by the private

respondents sufficiently rebutted the truth of the content of

petitioner's Certificate of Live Birth. of said rebutting

evidence, the most telling was the Deed of Extra-Judicial

Settlement of the Estate of the Deceased Isabel Chipongian

(Exh. "E") executed on July 20, 1982 by Vicente Benitez, and

Dr. Nilo Chipongian, a brother of Isabel. In their notarized

document, they stated that "(they) are the sole heirs of the

deceased Isabel Chipongian because she died without

descendants or ascendants". In executing this Deed, Vicente

Benitez effectively repudiated the Certificate of Live Birth of

petitioner where it appeared that he was petitioner's father.

The repudiation was made twenty-eight years after he

signed petitioner's Certificate of Live Birth.

IN VIEW WHEREOF, the petition for review is dismissed for

lack of merit. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

BABIERA v. CATOTAL

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 5

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 138493. June 15, 2000]

TEOFISTA BABIERA, petitioner, vs. PRESENTACION B.

CATOTAL, respondent.

DECISION

PANGANIBAN, J.:

A birth certificate may be ordered cancelled upon adequate

proof that it is fictitious. Thus, void is a certificate which

shows that the mother was already fifty-four years old at the

time of the child's birth and which was signed neither by the

civil registrar nor by the supposed mother. Because her

inheritance rights are adversely affected, the legitimate child

of such mother is a proper party in the proceedings for the

cancellation of the said certificate.

Statement of the Case

Submitted for this Courts consideration is a Petition for

Review on Certiorari[1] under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court,

seeking reversal of the March 18, 1999 Decision[2] of the

Court of Appeals[3] (CA) in CA-GR CV No. 56031. Affirming

the Regional Trial Court of Lanao del Norte in Special

Proceedings No. 3046, the CA ruled as follows:

"IN VIEW HEREOF, the appealed decision is hereby

AFFIRMED. Accordingly, the instant appeal is DISMISSED

for lack of merit. Costs against the defendant-appellant,

TEOFISTA BABIERA, a.k.a. Teofista Guinto."[4]

The dispositive portion of the affirmed RTC Decision reads:

"WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing findings and

pronouncements of the Court, judgment is hereby rendered,

to wit[:]

1) Declaring the Certificate of Birth of respondent Teofista

Guinto as null and void 'ab initio';

2) Ordering the respondent Local Civil Registrar of Iligan to

cancel from the registry of live birth of Iligan City BIRTH

CERTIFICATE recorded as Registry No. 16035;

Furnish copies of this decision to the Local Civil Registrar of

Iligan City, the City Prosecutor, counsel for private

respondent Atty. Tomas Cabili and to counsel for petitioner.

SO ORDERED."

"Presentacion B. Catotal (hereafter referred to as

PRESENTACION) filed with the Regional Trial Court of

Lanao del Norte, Branch II, Iligan City, a petition for the

cancellation of the entry of birth of Teofista Babiera (herafter

referred to as TEOFISTA) in the Civil Registry of Iligan City.

The case was docketed as Special Proceedings No. 3046.

"From the petition filed, PRESENTACION asserted 'that she

is the only surviving child of the late spouses Eugenio

Babiera and Hermogena Cariosa, who died on May 26,

1996 and July 6, 1990 respectively; that on September 20,

1996 a baby girl was delivered by 'hilot' in the house of

spouses Eugenio and Hermogena Babiera and without the

knowledge of said spouses, Flora Guinto, the mother of the

child and a housemaid of spouses Eugenio and Hermogena

Babiera, caused the registration/recording of the facts of

birth of her child, by simulating that she was the child of the

spouses Eugenio, then 65 years old and Hermogena, then

54 years old, and made Hermogena Babiera appear as the

mother by forging her signature x x x; that petitioner, then 15

years old, saw with her own eyes and personally witnessed

Flora Guinto give birth to Teofista Guinto, in their house,

assisted by 'hilot'; that the birth certificate x x x of Teofista

Guinto is void ab initio, as it was totally a simulated birth,

signature of informant forged, and it contained false entries,

to wit: a) The child is made to appear as the legitimate child

of the late spouses Eugenio Babiera and Hermogena

Cariosa, when she is not; b) The signature of Hermogena

Cariosa, the mother, is falsified/forged. She was not the

informant; c) The family name BABIERA is false and unlawful

and her correct family name is GUINTO, her mother being

single; d) Her real mother was Flora Guinto and her status,

an illegitimate child; The natural father, the carpenter, did not

sign it; that the respondent Teofista Barbiera's birth certificate

is void ab initio, and it is patently a simulation of birth, since it

is clinically and medically impossible for the supposed

parents to bear a child in 1956 because: a) Hermogena

Cariosa Babiera, was already 54 years old; b) Hermogena's

last child birth was in the year 1941, the year petitioner was

born; c) Eugenio was already 65 years old, that the void and

simulated birth certificate of Teofista Guinto would affect the

hereditary rights of petitioner who inherited the estate of

cancelled and declared void and theretofore she prays that

after publication, notice and hearing, judgment [be]

render[ed] declaring x x x the certificate of birth of

respondent Teofista Guinto as declared void, invalid and

ineffective and ordering the respondent local civil registrar of

Iligan to cancel from the registry of live birth of Iligan City

BIRTH CERTIFICATE recorded as Registry No. 16035.

"Finding the petition to be sufficient in form and substance,

the trial court issued an order directing the publication of the

petition and the date of hearing thereof 'in a newspaper, the

Local Civil Registrar of Iligan City, the office of the City

Prosecutor of Iligan City and TEOFISTA.

The Facts

The undisputed facts are summarized by the Court of

Appeals in this wise:

"TEOFISTA filed a motion to dismiss on the grounds that 'the

petition states no cause of action, it being an attack on the

legitimacy of the respondent as the child of the spouses

Eugenio Babiera and Hermogena Cariosa Babiera; that

plaintiff has no legal capacity to file the instant petition

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 6

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

pursuant to Article 171 of the Family Code; and finally that

the instant petition is barred by prescription in accordance

with Article 170 of the Family Code.' The trial court denied

the motion to dismiss.

"1) Respondent (plaintiff in the lower court a quo) does not

have the legal capacity to file the special proceeding of

appeal under CA GR No. CV-56031 subject matter of this

review on certiorari;

"Subsequently, 'Attys. Padilla, Ulindang and Padilla

appeared and filed an answer/opposition in behalf of private

respondent Teofista Babiera, [who] was later on substituted

by Atty. Cabili as counsel for private respondent.'

2) The special proceeding on appeal under CA GR No. CV56031 is improper and is barred by [the] statute of limitation

(prescription); [and]

"In the answer filed, TEOFISTA averred 'that she was always

known as Teofista Babiera and not Teofista Guinto; that

plaintiff is not the only surviving child of the late spouses

Eugenio Babiera and Hermogena C. Babiera, for the truth of

the matter [is that] plantiff Presentacion B. V. Catotal and

[defendant] Teofista Babiera are sisters of the full-blood. Her

Certificate of Birth, signed by her mother Hermogena

Babiera, x x x Certificate of Baptism, x x x Student's Report

Card x x x all incorporated in her answer, are eloquent

testimonies of her filiation. By way of special and affirmative

defenses, defendant/respondent contended that the petition

states no cause of action, it being an attack on the legitimacy

of the respondent as the child of the spouses Eugenio

Babiera and Hermogena Carioza Babiera; that plaintiff has

no legal capacity to file the instant petition pursuant to Article

171 of the Family Code; and finally that the instant petition is

barred by prescription in accordance with Article 170 of the

Family Code." [5]

Ruling of the Court of Appeals

The Court of Appeals held that the evidence adduced during

trial proved that petitioner was not the biological child of

Hermogena Babiera. It also ruled that no evidence was

presented to show that Hermogena became pregnant in

1959. It further observed that she was already 54 years old

at the time, and that her last pregnancy had occurred way

back in 1941. The CA noted that the supposed birth took

place at home, notwithstanding the advanced age of

Hermogena and its concomitant medical complications.

Moreover, petitioner's Birth Certificate was not signed by the

local civil registrar, and the signature therein, which was

purported to be that of Hermogena, was different from her

other signatures.

The CA also deemed inapplicable Articles 170 and 171 of the

Family Code, which stated that only the father could impugn

the child's legitimacy, and that the same was not subject to a

collateral attack. It held that said provisions contemplated a

situation wherein the husband or his heirs asserted that the

child of the wife was not his. In this case, the action involved

the cancellation of the childs Birth Certificate for being

void ab initio on the ground that the child did not belong to

either the father or the mother.

3) The Honorable Court of Appeals, the fifteenth division

utterly failed to hold, that the ancient public record of

petitioner's birth is superior to the self-serving oral testimony

of respondent."[7]

The Courts Ruling

The Petition is not meritorious.

First Issue: Subject of the Present Action

Petitioner contends that respondent has no standing to sue,

because Article 171[8] of the Family Code states that the

child's filiation can be impugned only by the father or, in

special circumstances, his heirs. She adds that the

legitimacy of a child is not subject to a collateral attack.

This argument is incorrect. Respondent has the requisite

standing to initiate the present action. Section 2, Rule 3 of

the Rules of Court, provides that a real party in interest is

one "who stands to be benefited or injured by the judgment

in the suit, or the party entitled to the avails of the suit." [9] The

interest of respondent in the civil status of petitioner stems

from an action for partition which the latter filed against the

former.[10] The case concerned the properties inherited by

respondent from her parents.

Moreover, Article 171 of the Family Code is not applicable to

the present case. A close reading of this provision shows that

it applies to instances in which the father impugns the

legitimacy of his wifes child. The provision, however,

presupposes that the child was the undisputed offspring of

the mother. The present case alleges and shows that

Hermogena did not give birth to petitioner. In other words,

the prayer herein is not to declare that petitioner is an

illegitimate child of Hermogena, but to establish that the

former is not the latter's child at all. Verily, the present action

does not impugn petitioners filiation to Spouses Eugenio

and Hermogena Babiera, because there is no blood relation

to impugn in the first place.

In Benitez-Badua v. Court of Appeals,[11] the Court ruled thus:

Hence, this appeal.[6]

"Petitioners insistence on the applicability of Articles 164,

166, 170 and 171 of the Family Code to the case at bench

cannot be sustained. These articles provide:

Issues

x x x.....x x x.....x x x

Petitioner presents the following assignment of errors:

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 7

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

"A careful reading of the above articles will show that they do

not contemplate a situation, like in the instant case, where a

child is alleged not to be the child of nature or biological child

of a certain couple. Rather, these articles govern a situation

where a husband (or his heirs) denies as his own a child of

his wife. Thus, under Article 166, it is the husband who can

impugn the legitimacy of said child by proving: (1) it was

physically impossible for him to have sexual intercourse, with

his wife within the first 120 days of the 300 days which

immediately preceded the birth of the child; (2) that for

biological or other scientific reasons, the child could not have

been his child; (3) that in case of children conceived through

artificial insemination, the written authorization or ratification

by either parent was obtained through mistake, fraud,

violence, intimidation or undue influence. Articles 170 and

171 reinforce this reading as they speak of the prescriptive

period within which the husband or any of his heirs should

file the action impugning the legitimacy of said child.

Doubtless then, the appellate court did not err when it

refused to apply these articles to the case at bench. For the

case at bench is not one where the heirs of the late Vicente

are contending that petitioner is not his child by Isabel.

Rather, their clear submission is that petitioner was not born

to Vicente and Isabel. Our ruling in Cabatbat-Lim vs.

Intermediate Appellate Court, 166 SCRA 451, 457 cited in

the impugned decision is apropos, viz:

Petitioners recourse to Article 263 of the New Civil Code

[now Art. 170 of the Family Code] is not well-taken. This legal

provision refers to an action to impugn legitimacy. It is

inapplicable to this case because this is not an action to

impugn the legitimacy of a child, but an action of the private

respondents to claim their inheritance as legal heirs of their

childless deceased aunt. They do not claim that petitioner

Violeta Cabatbat Lim is an illegitimate child of the deceased,

but that she is not the decedents child at all. Being neither

[a] legally adopted child, nor an acknowledged natural child,

nor a child by legal fiction of Esperanza Cabatbat, Violeta is

not a legal heir of the deceased."[12] (Emphasis supplied.)

Second Issue: Prescription

Petitioner next contends that the action to contest her status

as a child of the late Hermogena Babiera has already

prescribed. She cites Article 170 of the Family Code which

provides the prescriptive period for such action:

"Art. 170. The action to impugn the legitimacy of the child

shall be brought within one year from the knowledge of the

birth or its recording in the civil register, if the husband or, in

a proper case, any of his heirs, should reside in the city or

municipality where the birth took place or was recorded.

"If the husband or, in his default, all of his heirs do not reside

at the place of birth as defined in the first paragraph or where

it was recorded, the period shall be two years if they should

reside in the Philippines; and three years if abroad. If the

birth of the child has been concealed from or was unknown

to the husband or his heirs, the period shall be counted from

the discovery or knowledge of the birth of the child or of the

fact of registration of said birth, whichever is earlier."

This argument is bereft of merit. The present action involves

the cancellation of petitioners Birth Certificate; it does not

impugn her legitimacy. Thus, the prescriptive period set forth

in Article 170 of the Family Code does not apply. Verily, the

action to nullify the Birth Certificate does not prescribe,

because it was allegedly void ab initio.[13]

Third Issue: Presumption

Certificate

in

Favor

of

the

Birth

Lastly, petitioner argues that the evidence presented,

especially Hermogenas testimony that petitioner was not her

real child, cannot overcome the presumption of regularity in

the issuance of the Birth Certificate.

While it is true that an official document such as petitioners

Birth Certificate enjoys the presumption of regularity, the

specific facts attendant in the case at bar, as well as the

totality of the evidence presented during trial, sufficiently

negate such presumption. First, there were already

irregularities regarding the Birth Certificate itself. It was not

signed by the local civil registrar.[14] More important, the Court

of Appeals observed that the mothers signature therein was

different from her signatures in other documents presented

during the trial.

Second, the circumstances surrounding the birth of petitioner

show that Hermogena is not the former's real mother. For

one, there is no evidence of Hermogenas pregnancy, such

as medical records and doctors prescriptions, other than the

Birth Certificate itself. In fact, no witness was presented to

attest to the pregnancy of Hermogena during that time.

Moreover, at the time of her supposed birth, Hermogena was

already 54 years old. Even if it were possible for her to have

given birth at such a late age, it was highly suspicious that

she did so in her own home, when her advanced age

necessitated proper medical care normally available only in a

hospital.

The most significant piece of evidence, however, is the

deposition of Hermogena Babiera which states that she did

not give birth to petitioner, and that the latter was not hers

nor her husband Eugenios. The deposition reads in part:

"q.....Who are your children?

a.....Presentation and Florentino Babiera.

q.....Now, this Teofista Babiera claims that she is your

legitimate child with your husband Eugenio Babiera, what

can you say about that?

a.....She is not our child.

x x x.....x x x.....x x x

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 8

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

q.....Do you recall where she was born?

a.....In our house because her mother was our house helper.

q.....Could you recall for how long if ever this Teofista

Babiera lived with you in your residence?

a.....Maybe in 1978 but she [would] always go ou[t] from time

to time.

q.....Now, during this time, do you recall if you ever assert[ed]

her as your daughter with your husband?

a.....No, sir."[15]

Relying merely on the assumption of validity of the Birth

Certificate, petitioner has presented no other evidence other

than the said document to show that she is really

Hermogenas child. Neither has she provided any reason

why her supposed mother would make a deposition stating

that the former was not the latter's child at all.

All in all, we find no reason to reverse or modify the factual

finding of the trial and the appellate courts that petitioner was

not the child of respondents parents.

WHEREFORE, the Petition is hereby DENIED and the

assailed Decision AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

DE JESUS v. DIZON

THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 142877. October 2, 2001]

JINKIE CHRISTIE A. DE JESUS and JACQUELINE A. DE

JESUS, minors, represented by their mother,

CAROLINA A. DE JESUS, petitioners, vs. THE

ESTATE OF DECEDENT JUAN GAMBOA DIZON,

ANGELINA V. DIZON, CARLOS DIZON, FELIPE

DIZON, JUAN DIZON, JR. and MARYLIN DIZON

and asproper parties: FORMS MEDIA CORP.,

QUAD MANAGEMENT CORP., FILIPINAS PAPER

SALES CO., INC. and AMITY CONSTRUCTION &

INDUSTRIAL ENTERPRISES, INC., respondents.

DECISION

VITUG, J.:

The petition involves the case of two illegitimate

children who, having been born in lawful wedlock, claim to

be the illegitimate scions of the decedent in order to enforce

their respective shares in the latters estate under the rules

on succession.

Danilo B. de Jesus and Carolina Aves de Jesus got

married on 23 August 1964. It was during this marriage that

Jacqueline A. de Jesus and Jinkie Christie A. de Jesus,

herein petitioners, were born, the former on 01 March 1979

and the latter on 06 July 1982.

In a notarized document, dated 07 June 1991, Juan G.

Dizon acknowledged Jacqueline and Jinkie de Jesus as

being his own illegitimate children by Carolina Aves de

Jesus. Juan G. Dizon died intestate on 12 March 1992,

leaving behind considerable assets consisting of shares of

stock in various corporations and some real property. It was

on the strength of his notarized acknowledgment that

petitioners filed a complaint on 01 July 1993 for Partition

with Inventory and Accounting of the Dizon estate with the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 88, of Quezon City.

Respondents, the surviving spouse and legitimate

children of the decedent Juan G. Dizon, including the

corporations of which the deceased was a stockholder,

sought the dismissal of the case, arguing that the complaint,

even while denominated as being one for partition, would

nevertheless call for altering the status of petitioners from

being the legitimate children of the spouses Danilo de Jesus

and Carolina de Jesus to instead be the illegitimate children

of Carolina de Jesus and deceased Juan Dizon. The trial

court denied, due to lack of merit, the motion to dismiss and

the subsequent motion for reconsideration on, respectively,

13 September 1993 and 15 February 1994. Respondents

assailed the denial of said motions before the Court of

Appeals.

On 20 May 1994, the appellate court upheld the

decision of the lower court and ordered the case to be

remanded to the trial court for further proceedings. It ruled

that the veracity of the conflicting assertions should be

threshed out at the trial considering that the birth certificates

presented by respondents appeared to have effectively

contradicted petitioners allegation of illegitimacy.

On 03 January 2000, long after submitting their answer,

pre-trial brief and several other motions, respondents filed an

omnibus motion, again praying for the dismissal of the

complaint on the ground that the action instituted was, in

fact, made to compel the recognition of petitioners as being

the illegitimate children of decedent Juan G. Dizon and that

the partition sought was merely an ulterior relief once

petitioners would have been able to establish their status as

such heirs. It was contended, in fine, that an action for

partition was not an appropriate forum to likewise ascertain

the question of paternity and filiation, an issue that could only

be taken up in an independent suit or proceeding.

Finding credence in the argument of respondents, the

trial court, ultimately, dismissed the complaint of petitioners

for lack of cause of action and for being improper.[1] It

decreed that the declaration of heirship could only be made

in a special proceeding inasmuch as petitioners were

seeking the establishment of a status or right.

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 9

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

Petitioners assail the foregoing order of the trial court in

the instant petition for review on certiorari. Basically,

petitioners maintain that their recognition as being

illegitimate children of the decedent, embodied in an

authentic writing, is in itself sufficient to establish their status

as such and does not require a separate action for judicial

approval following the doctrine enunciated in Divinagracia

vs. Bellosillo.[2]

In their comment, respondents submit that the rule

in Divinagracia being relied by petitioners is inapplicable to

the case because there has been no attempt to impugn

legitimate filiation in Divinagracia. In praying for the

affirmance of dismissal of the complaint, respondents count

on the case of Sayson vs. Court of Appeals,[3] which has

ruled that the issue of legitimacy cannot be questioned in a

complaint for partition and accounting but must be

seasonably brought up in a direct action frontally addressing

the issue.

The controversy between the parties has been pending

for much too long, and it is time that this matter draws to a

close.

The filiation of illegitimate children, like legitimate

children, is established by (1) the record of birth appearing

in the civil register or a final judgment; or (2) an admission of

legitimate filiation in a public document or a private

handwritten instrument and signed by the parent

concerned. In the absence thereof, filiation shall be

proved by (1) the open and continuous possession of the

status of a legitimate child; or (2) any other means allowed

by the Rules of Court and special laws.[4] The due

recognition of an illegitimate child in a record of birth, a

will, a statement before a court of record, or in any

authentic writing is, in itself, a consummated act of

acknowledgment of the child, and no further court action

is required.[5] In fact, any authentic writing is treated not just

a ground for compulsory recognition; it is in itself a voluntary

recognition that does not require a separate action for

judicial approval.[6] Where, instead, a claim for recognition

is predicated on other evidence merely tending to prove

paternity, i.e., outside of a record of birth, a will, a

statement before a court of record or an authentic

writing, judicial action within the applicable statute of

limitations is essential in order to establish the childs

acknowledgment.[7]

A scrutiny of the records would show that petitioners

were born during the marriage of their parents. The

certificates of live birth would also identify Danilo de Jesus

as being their father.

There is perhaps no presumption of the law more firmly

established and founded on sounder morality and more

convincing reason than the presumption that children born in

wedlock

are

legitimate.[8]This

presumption

indeed

becomes conclusive in the absence of proof that there is

physical impossibility of access between the spouses during

the first 120 days of the 300 days which immediately

precedes the birth of the child due to (a) the physical

incapacity of the husband to have sexual intercourse with his

wife; (b) the fact that the husband and wife are living

separately in such a way that sexual intercourse is not

possible; or (c) serious illness of the husband, which

absolutely prevents sexual intercourse.[9] Quite remarkably,

upon the expiration of the periods set forth in Article 170,

[10]

and in proper cases Article 171,[11] of the Family Code

(which took effect on 03 August 1988), the action to impugn

the legitimacy of a child would no longer be legally feasible

and the status conferred by the presumption becomes fixed

and unassailable.[12]

Succinctly, in an attempt to establish their illegitimate

filiation to the late Juan G. Dizon, petitioners, in effect, would

impugn their legitimate status as being children of Danilo de

Jesus and Carolina Aves de Jesus. This step cannot be

aptly done because the law itself establishes the legitimacy

of children conceived or born during the marriage of the

parents. The presumption of legitimacy fixes a civil

status for the child born in wedlock, and only the father,

[13]

or in exceptional instances the latters heirs, [14] can

contest in an appropriate action the legitimacy of a child

born to his wife. Thus, it is only when the legitimacy of a

child has been successfully impugned that the paternity

of the husband can be rejected.

Respondents correctly argued that petitioners hardly

could find succor in Divinagracia. In said case, the Supreme

Court remanded to the trial court for further proceedings the

action for partition filed by an illegitimate child who had

claimed to be an acknowledged spurious child by virtue of a

private document, signed by the acknowledging parent,

evidencing such recognition. It was not a case of legitimate

children asserting to be somebody elses illegitimate

children. Petitioners totally ignored the fact that it was not for

them, given the attendant circumstances particularly, to

declare that they could not have been the legitimate children,

clearly opposed to the entries in their respective birth

certificates, of Danilo and Carolina de Jesus.

The rule that the written acknowledgment made by the

deceased Juan G. Dizon establishes petitioners alleged

illegitimate filiation to the decedent cannot be validly invoked

to be of any relevance in this instance. This issue, i.e.,

whether petitioners are indeed the acknowledged illegitimate

offsprings of the decedent, cannot be aptly adjudicated

without an action having been first been instituted to impugn

their legitimacy as being the children of Danilo B. de Jesus

and Carolina Aves de Jesus born in lawful

wedlock. Jurisprudence is strongly settled that the

paramount declaration of legitimacy by law cannot be

attacked collaterally,[15] one that can only be repudiated or

contested in a direct suit specifically brought for that

purpose.[16] Indeed, a child so born in such wedlock shall be

considered legitimate although the mother may have

declared against its legitimacy or may have been sentenced

as having been an adulteress.[17]

WHEREFORE, the foregoing disquisitions considered,

the instant petition is DENIED. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 10

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

The facts as alleged by petitioner are as follows:

Corazon G. Garcia is legally married to but living

separately from Ramon M. Yulo for more than ten (10) years

at the time of the institution of the said civil case. Corazon

cohabited with the late William Liyao from 1965 up to the

time of Williams untimely demise on December 2, 1975.

They lived together in the company of Corazons two (2)

children from her subsisting marriage, namely:

Enrique and Bernadette, both surnamed Yulo, in a

succession of rented houses in Quezon City and Manila.

This was with the knowledge of William Liyaos legitimate

children, Tita Rose L. Tan and Linda Christina Liyao-Ortiga,

from his subsisting marriage with Juanita Tanhoti Liyao. Tita

Rose and Christina were both employed at the Far East

Realty Investment, Inc. of which Corazon and William were

then vice president and president, respectively.

LIYAO v. TANHOTI-LIYAO

SECOND DIVISION

[G.R. No. 138961. March 7, 2002]

WILLIAM LIYAO, JR., represented by his mother Corazon

Garcia, petitioner, vs. JUANITA TANHOTI-LIYAO,

PEARL MARGARET L. TAN, TITA ROSE L. TAN

AND LINDA CHRISTINA LIYAO, respondents.

DECISION

DE LEON, JR., J.:

Before us is a petition for review on certiorari assailing

the decision dated June 4, 1999 of the Court of Appeals in

CA-G.R. C.V. No. 45394[1] which reversed the decision of the

Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Pasig, Metro Manila, Branch

167 in declaring William Liyao, Jr. as the illegitimate

(spurious) son of the deceased William Liyao and ordering

Juanita Tanhoti-Liyao, Pearl Margaret L. Tan, Tita Rose L.

Tan and Linda Christina Liyao to recognize and acknowledge

William Liyao, Jr. as a compulsory heir of the deceased

William Liyao and entitled to all successional rights as such

and to pay the costs of the suit.

On November 29,1976, William Liyao, Jr., represented

by his mother Corazon G. Garcia, filed Civil Case No. 24943

before the RTC of Pasig, Branch 167 which is an action for

compulsory recognition as the illegitimate (spurious) child of

the late William Liyao against herein respondents, Juanita

Tanhoti-Liyao, Pearl Margaret L. Tan, Tita Rose L. Tan and

Linda Christina Liyao.[2] The complaint was later amended to

include the allegation that petitioner was in continuous

possession and enjoyment of the status of the child of said

William Liyao, petitioner having been recognized and

acknowledged as such child by the decedent during his

lifetime."[3]

Sometime in 1974, Corazon bought a lot from Ortigas

and Co. which required the signature of her husband,

Ramon Yulo, to show his consent to the aforesaid sale. She

failed to secure his signature and, had never been in touch

with him despite the necessity to meet him. Upon the advice

of William Liyao, the sale of the parcel of land located at the

Valle Verde Subdivision was registered under the name of

Far East Realty Investment, Inc.

On June 9, 1975, Corazon gave birth to William Liyao,

Jr. at the Cardinal Santos Memorial Hospital. During her

three (3) day stay at the hospital, William Liyao visited and

stayed with her and the new born baby, William, Jr. (Billy). All

the medical and hospital expenses, food and clothing were

paid under the account of William Liyao. William Liyao even

asked his confidential secretary, Mrs. Virginia Rodriguez, to

secure a copy of Billys birth certificate. He likewise

instructed Corazon to open a bank account for Billy with the

Consolidated Bank and Trust Company[4] and gave weekly

amounts to be deposited therein.[5] William Liyao would bring

Billy to the office, introduce him as his good looking son and

had their pictures taken together.[6]

During the lifetime of William Liyao, several pictures

were taken showing, among others, William Liyao and

Corazon together with Billys godfather, Fr. Julian Ruiz,

William Liyaos legal staff and their wives while on vacation

in Baguio.[7] Corazon also presented pictures in court to

prove that that she usually accompanied William Liyao while

attending various social gatherings and other important

meetings.[8] During the occasion of William Liyaos last

birthday on November 22, 1975 held at the Republic

Supermarket, William Liyao expressly acknowledged Billy as

his son in the presence of Fr. Ruiz, Maurita Pasion and other

friends and said, Hey, look I am still young, I can still make

a good looking son."[9] Since birth, Billy had been in

continuous possession and enjoyment of the status of a

recognized and/or acknowledged child of William Liyao by

the latters direct and overt acts. William Liyao supported

Billy and paid for his food, clothing and other material needs.

However, after William Liyaos death, it was Corazon who

provided sole support to Billy and took care of his tuition fees

at La Salle, Greenhills. William Liyao left his personal

belongings, collections, clothing, old newspaper clippings

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 11

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

and laminations at the house in White Plains where he

shared his last moments with Corazon.

Testifying for the petitioner, Maurita Pasion declared

that she knew both Corazon G. Garcia and William Liyao

who were godparents to her children. She used to visit

Corazon and William Liyao from 1965-1975. The two

children of Corazon from her marriage to Ramon Yulo,

namely, Bernadette and Enrique (Ike), together with some

housemaids lived with Corazon and William Liyao as one

family. On some occasions like birthdays or some other

celebrations, Maurita would sleep in the couples residence

and cook for the family. During these occasions, she would

usually see William Liyao in sleeping clothes. When

Corazon, during the latter part of 1974, was pregnant with

her child Billy, Maurita often visited her three (3) to four (4)

times a week in Greenhills and later on in White Plains

where she would often see William Liyao. Being a close

friend of Corazon, she was at the Cardinal Santos Memorial

Hospital during the birth of Billy. She continuously visited

them at White Plains and knew that William Liyao, while

living with her friend Corazon, gave support by way of

grocery supplies, money for household expenses and

matriculation fees for the two (2) older children, Bernadette

and Enrique. During William Liyaos birthday on November

22, 1975 held at the Republic Supermarket Office, he was

carrying Billy and told everybody present, including his two

(2) daughters from his legal marriage, Look, this is my son,

very guapo and healthy.[10] He then talked about his plan for

the baptism of Billy before Christmas. He intended to make it

engrande and make the bells of San Sebastian Church

ring.[11] Unfortunately, this did not happen since William

Liyao passed away on December 2, 1975. Maurita attended

Mr. Liyaos funeral and helped Corazon pack his clothes.

She even recognized a short sleeved shirt of blue and

gray[12] which Mr. Liyao wore in a photograph[13] as well as

another shirt of lime green[14] as belonging to the deceased. A

note was also presented with the following inscriptions: To

Cora, Love From William.[15] Maurita remembered having

invited the couple during her mothers birthday where the

couple had their pictures taken while exhibiting affectionate

poses with one another. Maurita knew that Corazon is still

married to Ramon Yulo since her marriage has not been

annulled nor is Corazon legally separated from her said

husband. However, during the entire cohabitation of William

Liyao with Corazon Garcia, Maurita had not seen Ramon

Yulo or any other man in the house when she usually visited

Corazon.

Gloria Panopio testified that she is the owner of a

beauty parlor and that she knew that Billy is the son of her

neighbors, William Liyao and Corazon Garcia, the latter

being one of her customers. Gloria met Mr. Liyao at

Corazons house in Scout Delgado, Quezon City in the

Christmas of 1965. Gloria had numerous occasions to see

Mr. Liyao from 1966 to 1974 and even more so when the

couple transferred to White Plains, Quezon City from 19741975. At the time Corazon was conceiving, Mr. Liyao was

worried that Corazon might have another miscarriage so he

insisted that she just stay in the house, play mahjong and not

be bored. Gloria taught Corazon how to play mahjong and

together with Atty. Brillantes wife and sister-in-law, had

mahjong sessions among themselves. Gloria knew that Mr.

Liyao provided Corazon with a rented house, paid the salary

of the maids and food for Billy. He also gave Corazon

financial support. Gloria knew that Corazon is married but is

separated from Ramon Yulo although Gloria never had any

occasion to see Mr. Yulo with Corazon in the house where

Mr. Liyao and Corazon lived.

Enrique Garcia Yulo testified that he had not heard

from his father, Ramon Yulo, from the time that the latter

abandoned and separated from his family. Enrique was

about six (6) years old when William Liyao started to live with

them up to the time of the latters death on December 2,

1975. Mr. Liyao was very supportive and fond of Enriques

half brother, Billy. He identified several pictures showing Mr.

Liyao carrying Billy at the house as well as in the office.

Enriques testimony was corroborated by his sister,

Bernadette Yulo, who testified that the various pictures

showing Mr. Liyao carrying Billy could not have been

superimposed and that the negatives were in the possession

of her mother, Corazon Garcia.

Respondents, on the other hand, painted a different

picture of the story.

Linda Christina Liyao-Ortiga stated that her parents,

William Liyao and Juanita Tanhoti-Liyao, were legally

married.[16] Linda grew up and lived with her parents at San

Lorenzo Village, Makati, Metro Manila until she got married;

that her parents were not separated legally or in fact and that

there was no reason why any of her parents would institute

legal separation proceedings in court. Her father lived at their

house in San Lorenzo Village and came home regularly.

Even during out of town business trips or for conferences

with the lawyers at the office, her father would change his

clothes at home because of his personal hygiene and habits.

Her father reportedly had trouble sleeping in other peoples

homes. Linda described him as very conservative and a

strict disciplinarian. He believed that no amount of success

would compensate for failure of a home. As a businessman,

he was very tough, strong, fought for what he believed in and

did not give up easily. He suffered two strokes before the

fatal attack which led to his death on December 2, 1975. He

suffered a stroke at the office sometime in April-May 1974

and was attended by Dr. Santiago Co. He then stayed in the

house for two (2) to three (3) months for his therapy and

acupuncture treatment. He could not talk, move, walk, write

or sign his name. In the meantime, Linda and her sister, Tita

Rose Liyao-Tan, ran the office. She handled the collection of

rents while her sister referred legal matters to their lawyers.

William Liyao was bedridden and had personally changed.

He was not active in business and had dietary restrictions.

Mr. Liyao also suffered a milder stroke during the latter part

of September to October 1974. He stayed home for two (2)

to three (3) days and went back to work. He felt depressed,

however, and was easily bored. He did not put in long hours

in the office unlike before and tried to spend more time with

his family.

Linda testified that she knew Corazon Garcia is still

married to Ramon Yulo. Corazon was not legally separated

from her husband and the records from the Local Civil

Registrar do not indicate that the couple obtained any

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 12

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

annulment[17] of their marriage. Once in 1973, Linda chanced

upon Ramon Yulo picking up Corazon Garcia at the

company garage. Immediately after the death of Lindas

father, Corazon went to Lindas office for the return of the

formers alleged investments with the Far East Realty

Investment, Inc. including a parcel of land sold by Ortigas

and Company. Linda added that Corazon, while still a VicePresident of the company, was able to take out documents,

clothes and several laminated pictures of William Liyao from

the office. There was one instance when she was told by the

guards, Mrs. Yulo is leaving and taking out things

again.[18] Linda then instructed the guards to bring Mrs. Yulo

to the office upstairs but her sister, Tita Rose, decided to let

Corazon Garcia go. Linda did not recognize any article of

clothing which belonged to her father after having been

shown three (3) large suit cases full of mens clothes,

underwear, sweaters, shorts and pajamas.

Tita Rose Liyao-Tan testified that her parents were

legally married and had never been separated. They resided

at No. 21 Hernandez Street, San Lorenzo Village, Makati up

to the time of her fathers death on December 2, 1975. [19] Her

father suffered two (2) minor cardio-vascular arrests (CVA)

prior to his death. During the first heart attack sometime

between April and May 1974, his speech and hands were

affected and he had to stay home for two (2) to three (3)

months under strict medication, taking aldomet, serpadil and

cifromet which were prescribed by Dr. Bonifacio Yap, for high

blood pressure and cholesterol level control.[20] Tita Rose

testified that after the death of Mr. Liyao, Corazon Garcia

was paid the amount of One Hundred Thousand Pesos

(P100,000.00) representing her investment in the Far East

Realty Investment Inc. Tita Rose also stated that her family

never received any formal demand that they recognize a

certain William Liyao, Jr. as an illegitimate son of her father,

William Liyao. After assuming the position of President of the

company, Tita Rose did not come across any check signed

by her late father representing payment to lessors as rentals

for the house occupied by Corazon Garcia. Tita Rose added

that the laminated photographs presented by Corazon

Garcia are the personal collection of the deceased which

were displayed at the latters office.

The last witness who testified for the respondents was

Ramon Pineda, driver and bodyguard of William Liyao from

1962 to 1974, who said that he usually reported for work at

San Lorenzo Village, Makati to pick up his boss at 8:00

oclock in the morning. At past 7:00 oclock in the evening,

either Carlos Palamigan or Serafin Villacillo took over as

night shift driver. Sometime between April and May 1974, Mr.

Liyao got sick. It was only after a month that he was able to

report to the office. Thereafter, Mr. Liyao was not able to

report to the office regularly. Sometime in September 1974,

Mr. Liyao suffered from another heart attack. Mr. Pineda

added that as a driver and bodyguard of Mr. Liyao, he ran

errands for the latter among which was buying medicine for

him like capasid and aldomet. On December 2, 1975, Mr.

Pineda was called inside the office of Mr. Liyao. Mr. Pineda

saw his employer leaning on the table. He tried to massage

Mr. Liyaos breast and decided later to carry and bring him to

the hospital but Mr. Liyao died upon arrival thereat. Mrs.

Liyao and her daughter, Linda Liyao-Ortiga were the first to

arrive at the hospital.

Mr. Pineda also declared that he knew Corazon Garcia

to be one of the employees of the Republic Supermarket.

People in the office knew that she was married. Her

husband, Ramon Yulo, would sometimes go to the office.

One time, in 1974, Mr. Pineda saw Ramon Yulo at the office

garage as if to fetch Corazon Garcia. Mr. Yulo who was also

asking about cars for sale, represented himself as car dealer.

Witness Pineda declared that he did not know anything

about the claim of Corazon. He freely relayed the information

that he saw Mr. Yulo in the garage of Republic Supermarket

once in 1973 and then in 1974 to Atty. Quisumbing when he

went to the latters law office. Being the driver of Mr. Liyao for

a number of years, Pineda said that he remembered having

driven the group of Mr. Liyao, Atty. Astraquillo, Atty.

Brillantes, Atty. Magno and Atty. Laguio to Baguio for a

vacation together with the lawyers wives. During his

employment, as driver of Mr. Liyao, he does not remember

driving for Corazon Garcia on a trip to Baguio or for activities

like shopping.

On August 31, 1993, the trial court rendered a decision,

the dispositive portion of which reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the

plaintiff and against the defendants as follows:

(a) Confirming the appointment of Corazon G. Garcia as the

guardian ad litem of the minor William Liyao, Jr.;

(b) Declaring the minor William Liyao, Jr. as the illegitimate

(spurious) son of the deceased William Liyao;

(c) Ordering the defendants Juanita Tanhoti Liyao, Pearl

Margaret L. Tan, Tita Rose L. Tan and Christian Liyao, to

recognize, and acknowledge the minor William Liyao, Jr. as

a compulsory heir of the deceased William Liyao, entitled to

all succesional rights as such; and

(d) Costs of suit.[21]

In ruling for herein petitioner, the trial court said it was

convinced by preponderance of evidence that the deceased

William Liyao sired William Liyao, Jr. since the latter was

conceived at the time when Corazon Garcia cohabited with

the deceased. The trial court observed that herein petitioner

had been in continuous possession and enjoyment of the

status of a child of the deceased by direct and overt acts of

the latter such as securing the birth certificate of petitioner

through his confidential secretary, Mrs. Virginia Rodriguez;

openly and publicly acknowledging petitioner as his son;

providing sustenance and even introducing herein petitioner

to his legitimate children.

The Court of Appeals, however, reversed the ruling of

the trial court saying that the law favors the legitimacy rather

than the illegitimacy of the child and the presumption of

legitimacy is thwarted only on ethnic ground and by proof

that marital intimacy between husband and wife was

PERSONS and FAMILY RELATIONS (Atty. Vincent Juan) 13

4TH EXAM COVERAGE CASE COMPILATION

physically impossible at the period cited in Article 257 in

relation to Article 255 of the Civil Code. The appellate court

gave weight to the testimonies of some witnesses for the

respondents that Corazon Garcia and Ramon Yulo who were

still legally married and have not secured legal separation,

were seen in each others company during the supposed

time that Corazon cohabited with the deceased William

Liyao. The appellate court further noted that the birth

certificate and the baptismal certificate of William Liyao, Jr.

which were presented by petitioner are not sufficient to

establish proof of paternity in the absence of any evidence

that the deceased, William Liyao, had a hand in the

preparation of said certificates and considering that his

signature does not appear thereon. The Court of Appeals

stated that neither do family pictures constitute competent

proof of filiation. With regard to the passbook which was

presented as evidence for petitioner, the appellate court

observed that there was nothing in it to prove that the same

was opened by William Liyao for either petitioner or Corazon

Garcia since William Liyaos signature and name do not

appear thereon.

His motion for reconsideration having been denied,

petitioner filed the present petition.

It must be stated at the outset that both petitioner and

respondents have raised a number of issues which relate

solely to the sufficiency of evidence presented by petitioner

to establish his claim of filiation with the late William Liyao.

Unfortunately, both parties have consistently overlooked the

real crux of this litigation: May petitioner impugn his own

legitimacy to be able to claim from the estate of his

supposed father, William Liyao?

We deny the present petition.

Under the New Civil Code, a child born and conceived

during a valid marriage is presumed to be legitimate. [22] The

presumption of legitimacy of children does not only flow out

from a declaration contained in the statute but is based on

the broad principles of natural justice and the supposed

virtue of the mother. The presumption is grounded in a policy

to protect innocent offspring from the odium of illegitimacy.[23]

The presumption of legitimacy of the child, however, is

not conclusive and consequently, may be overthrown by

evidence to the contrary. Hence, Article 255 of the New Civil

Code[24]provides:

Article 255. Children born after one hundred and eighty days

following the celebration of the marriage, and before three

hundred days following its dissolution or the separation of

the spouses shall be presumed to be legitimate.

Against this presumption no evidence shall be admitted

other than that of the physical impossibility of the husband

having access to his wife within the first one hundred and

twenty days of the three hundred which preceded the birth of

the child.

1) By the impotence of the husband;

2) By the fact that husband and wife were living separately in

such a way that access was not possible;

3) By the serious illness of the husband.