Transfer Ownership Cases

Diunggah oleh

Ariel Mark PilotinHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Transfer Ownership Cases

Diunggah oleh

Ariel Mark PilotinHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

AURORA ALCANTARA-DAUS, vs.

Spouses

HERMOSO and SOCORRO DE LEON

December 6, 1975 was thus binding upon the

parties thereto.

Facts:

A contract of sale is consensual. It is

perfected by mere consent,[10] upon a meeting

of the minds[11] on the offer and the acceptance

thereof based on subject matter, price and

terms of payment.[12] At this stage, the sellers

ownership of the thing sold is not an element in

the perfection of the contract of sale.

Respondents alleged that they are the owners

of a parcel of land described as: No. 4786 of

the Cadastral Survey of San Manuel situated in

the Municipality of San Manuel, Bounded on the

NW., by Lot No. 4785; and on the SE., by Lot

Nos. 11094 & 11096; containing an area of Four

Thousand Two Hundred Twelve (4,212) sq. m.,

more or less. Covered by Original Certificate of

Title No. 22134 of the Land Records of

Pangasinan.

which Hermoso de Leon inherited from his

father Marcelino de Leon by virtue of a Deed of

Extra-judicial Partition. Sometime in the early

1960s, respondents engaged the services of

the late Atty. Florencio Juan to take care of the

documents of the properties of his

parents. Atty. Juan let them sign voluminous

documents. After the death of Atty. Juan, some

documents surfaced and most revealed that

their properties had been conveyed by sale or

quitclaim to Hermosos brothers and sisters, to

Atty. Juan and his sisters, when in truth and in

fact, no such conveyances were ever intended

by them. His signature in the Deed of Extrajudicial Partition with Quitclaim made in favor of

Rodolfo de Leon was forged. They discovered

that the land in question was sold by Rodolfo de

Leon to Aurora Alcantara. They demanded

annulment of the document and reconveyance

but defendants refused

Aurora Alcantara-Daus that she bought the land

in question in good faith and for value. [She]

has been in continuous, public, peaceful, open

possession over the same and has been

appropriating the produce thereof without

objection from anyone.

Issue:

1. Whether or not the Deed of Absolute Sale \

executed by Rodolfo de Leon over the land in

question in favor of petitioner was perfected

and binding upon the parties therein?

Ruling:

Petition has no merit.

Petitioner argues that, having been

perfected, the Contract of Sale executed on

The contract, however, creates an

obligation on the part of the seller to transfer

ownership and to deliver the subject matter of

the contract.[13] It is during the delivery that the

law requires the seller to have the right to

transfer ownership of the thing sold.[14] In

general, a perfected contract of sale cannot be

challenged on the ground of the sellers nonownership of the thing sold at the time of the

perfection of the contract.[15]

Further, even after the contract of sale has

been perfected between the parties, its

consummation by delivery is yet another

matter. It is through tradition or delivery that the

buyer acquires the real right of ownership over

the thing sold.[16]

Undisputed is the fact that at the time of the

sale, Rodolfo de Leon was not the owner of the

land he delivered to petitioner. Thus, the

consummation of the contract and the

consequent transfer of ownership would

depend on whether he subsequently acquired

ownership of the land in accordance with Article

1434 of the Civil Code.[17] Therefore, we need to

resolve the issue of the authenticity and the due

execution of the Extrajudicial Partition and

Quitclaim in his favor.

2. Sampaguita Pictures vs Jalwindor

Manufacturers

Facts:

Sampaguita is the owner of Sampaguita

Pictures Building. The roof deck and all existing

improvements were leased to Capitol 300. It

was agreed that:

Said premises shal be used by

said club for social purposes.

All imoprovements made by

lessee shall belong to lessor

without any reimbursement

Improvements shall be

considered part of the monthly

rental fee

Capitol purchased on credit from

Jalwindor glass and wooden jalousies.

The parties submitted to the trial court a

Compromise Agreement wherein Capitol

acknowledged its indebtedness to Jalwindor in

the amount of P9,531.09, payable in monthly

installments of at least P300.00 a month.

Capitol was not able to pay rentals to

Sampaguita. Capitol was ejected from the

building. Capitol failed to comply with the terms

of the compromise agreement. Sheriff made

levy on the glass and wooden jalousies.

Sampaguita filed a third party claim alleging

that its the owner of said materials and not

capitol.

On the other hand, Capitol likewise failed to

comply with the terms of the Compromise

Agreement, and on July 31, 1965, the Sheriff of

Quezon City made levy on the glass and

wooden jalousies in question. Sampaguita filed

a third party claim alleging that it is the owner of

said materials and not Capitol, Jalwindor

however, filed an indemnity bond in favor of the

Sheriff and the items were sold public auction

on August 30, 1965 with Jalwindor as the

highest bidder for P6,000.00.

Issue: Who owns the glass and wooden

jalousie windows?

Samapaguita.

When the glass and wooden jalousies in

question were delivered and installed in the

leased premises, Capitol became the owner

thereof. Ownership is not transferred by

perfection of the contract but by delivery, either

actual or constructive. This is true even if the

purchase has been made on credit, as in the

case at bar. Payment of the purchase price is

not essential to the transfer of ownership as

long as the property sold has been delivered.

Ownership is acquired from the moment the

thing sold was delivered to vendee, as when it

is placed in his control and possession. (Arts.

1477, 1496 and 1497, Civil Code of the Phil.)

Capitol entered into a lease Contract with

Sampaguita in 1964, and the latter became the

owner of the items in question by virtue of the

agreement in said contract "that all permanent

improvements made by lessee shall belong to

the lessor and that said improvements have

been considered as part of the monthly rentals."

When levy or said items was made on July 31,

1965, Capitol, the judgment debtor, was no

longer the owner thereof.

The action taken by Sampaguita to protect its

interest is sanctioned by Section 17, Rule 39 of

the Rules of Court, which reads:

Section 17, Proceedings where

property claimed by third person.

... The officer is not liable for

damages for the taking or

keeping of the property to any

third-party claimant unless a

claim is made by the latter and

unless an action for damages is

brought by him against the

officer within one hundred twenty

(120) days from the date of the

filing of the bond. But nothing

herein contained shall prevent

claimant from vindicating his

claim to the property by any

action.

It is, likewise, recignized in the case of Bayer

Phil., Inc. vs. Agana, et al., 63 SCRA 358,

wherein the Court declared, "that the rights of

third party claimants over certain properties

levied upon by the sheriff to satisfy the

judgment, may not be taken up in the case

where such claims are presented but in a

separate and independent action instituted by

claimants. ... and should a third-party appear to

claim is denied, the remedy contemplated by

the rules in the filing by said party of a

reinvicatiry action against the execution creditor

or the purchaser of the property after the sale is

completed or that a complaint for damages to

be charged against the bond filed by the

creditor in favor of the sheriff. ... Thus, when a

property levied upon by the sheriff pursuant to a

writ of execution is claimed by a third person in

a sworn statement of ownership thereof, as

prescribed by the rules, an entirely different

matter calling for a new adjudication arises."

The items in question were illegally levied upon

since they do not belong to the judgemnt

debtor. The power of the Court in execution of

judgment extends only to properties

unquestionably belonging to the judgment

debtor. The fact that Capitol failed to pay

Jalwindor the purchase price of the items levied

upon did not prevent the transfer of ownership

to Capitol. The complaint of Sampaguita to

nullify the Sheriff's sale well-founded, and

should prosper. Execution sales affect the rights

of judgment debtor only, and the purchaser in

the auction sale acquires only the right as the

debtor has at the time of sale. Since the items

already belong to Sampaguita and not to

Capitol, the judgment debtor, the levy and

auction sale are, accordingly, null and void. It is

well-settled in this jurisdiction that the sheriff is

not authorized to attach property not belonging

to the judgment debtor. (Arabay, Inc. vs.

Salvador, et al., 3 PHILAJUR, 413 [1978],

Herald Publishing vs. Ramos, 88 Phil. 94, 100).

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is

hereby reversed, and plaintiff-appellant

Sampaguita is declared the lawful owner of the

disputed glass and wooden jalousies.

Defendant-appellee Jalwindor is permanently

enjoined from detaching said items from the

roofdeck of the Sampaguita Pictures Building,

and is also ordered to pay plaintiff-appellant the

sum of P1,000.00 for and as attorney's fees,

and costs.

PNB v. Lo

Villamor, J.

Parties:

Philippine National Bank, plaintiff-appellee,

Severo Eugenio Lo, et al. defendants

Severio Eugenio Lo, Ng Khey Ling and Yep

Seng, appellants

Facts:

1916 Severo Eugenio Lo and Ng Khey

Ling together with J.A. Say Lian Ping,

Ko Tiao Hun, On Yem Ke Lam and Co

Sieng Peng formed a commercial

partnership under the name of Tai Sing

Co., with a capital of P40,000

contributed by said partners.

Articles of Copartnership states that:

Partnership was to last for 5

years from after the date of its

organization

o Purpose: to do business in the

City of Iloilo or in any other part

of the Philippines the partners

might desire; purchase and sale

of merchandise, goods, and

native, as well as Chinese and

Japanese products

o J.A. Say Lian Ping was

appointed general manager

A. Say Lian Ping executed a power of

attorney in favor of A. Y. Kelam,

authorizing him to act in his stead as

manager and administrator of Tai Sing

& Co. and to obtain a loan of P8,000 in

current account from PNB.

Kelam mortgaged certain personal

property of the partnership.

The credit was renewed several times

and Kelam, as attorney-in-fact of Tai

Sing & Co., executed a chattel mortgage

in favor of PNB as security as security

for a loan P20,000.

This mortgage was again renewed and

Kelam as attorney-in-fact of Tai Sing &

Co. executed another chattel mortgage

for the said sum of P20,000.

1920 Yap Seng, Severo Lo, Kelam

and Ng Khey Ling, the latter

represented by M. Pineda Tayenko,

executed a power of attorney in favor of

Sy Tit.

By virtue of the power of attorney, Sy Tit

representing Tai Sing & Co. obtained a

credit of P20,000 from PNB in 1921 and

executed a chattel mortgage on certain

personal property belonging to the

partnership.

Defendants had been using this

commercial credit in a current account

with the plaintiff bank from 1918 1922

and as of December 31, 1924 the debit

balance of this account P 20, 239.

PNB claims in the complaint this amount

and an interest of P16, 518.74.

Eugenio Los defense:

o Tai Sing & Co. was not a

general partnership.

o Commercial credit in current

account which Tai Sing & Co.

obtained from PNB had not been

authorized by the board nor was

the person who subscribed said

contract authorized under the

articles of copartnership

Trial Court: in favor of PNB

o

ISSUE:

Whether or not Tai Sing & Co. is a general

partnership in that the appellants can be

held liable to pay PNB

HELD: Yes. Tai Sing & Co. is a general

partnership

RATIO:

Appellants admit and it appears from the

articles of copartnership that Tai Sing &

Co. is a general partnership and it was

registered in the mercantile register of

Iloilo.

The fact that the partners opt to use Tai

Sing & Co. as the firm name does not

affect the liability of the general partners

to third parties under Article127 of the

Code of Commerce. Jurisprudence

states that:

o

o

o

The object of article 126 of the

Code of Commerce in requiring

a general partnership to transact

business under the name of all

its members, of several of them,

or of one only, is to protect the

public from imposition and fraud

It is for the protection of the

creditors rather than of the

partners themselves.

The law must be unlawful and

unenforceable only as between

the partners and at the instance

of the violating party, but not in

the sense of depriving innocent

parties of their rights who may

have dealt with the offenders in

ignorance of the latter having

violated the law.

Contracts entered into by

commercial

associations

defectively organized are valid

when voluntarily executed by the

parties, and the only question is

whether or not they complied

with the agreement. Therefore,

the defendants cannot invoke in

their defense the anomaly in the

firm

name

which

they

themselves adopted.

As to the alleged death of the manager,

Say Lian Ping before Kelam executed

the contracts of mortgage with PNB, this

would not affect the liability of the

partnership

o Kelam was a partner who

contracted in the name of the

partnership and the other

partners did not object

o Lo, Khey Ling, and Yap Seng

appointed Sy Tit as manager,

and he obtained from PNB the

credit in current account

Trial Court correctly held defendants to

be jointly and severally liable to PNB

This is in accordance with Article 127 of

the Code of Commerce all the

members of a general partnership, be

they managing partners thereof or not,

shall be personally and solidarily liable

with all their property, for the results of

the transactions made in the name and

for the account of the partnership, under

the signature of the latter, and by a

person authorized to use it.

Norkis Distributor vs. CA

G.R. No. 91029, February 7,1991; 193

SCRA 694

FACTS:

Petitioner Norkis Distributors, Inc. is the

distributor of Yamaha motorcycles in

Negros Occidental. On September 20,

1979, private respondent Alberto

Nepales bought from the Norkis Bacolod

branch

a

brand

new

Yamaha

Wonderbike motorcycle Model YL2DX.

The price of P7,500.00 was payable by

means of a Letter of Guaranty from the

DBP, which Norkis agreed to accept.

Credit was extended to Nepales for the

price of the motorcycle payable by DBP

upon release of his motorcycle loan. As

security for the loan, Nepales would

execute a chattel mortgage on the

motorcycle in favor of DBP. Petitioner

issued a sales invoice which Nepales

signed in conformity with the terms of

the sale. In the meantime, however, the

motorcycle

remained

in

Norkis

possession. On January 22, 1980, the

motorcycle was delivered to a certain

Julian Nepales, allegedly the agent of

Alberto Nepales. The motorcycle met an

accident on February 3, 1980 at

Binalbagan, Negros Occidental. An

investigation conducted by the DBP

revealed that the unit was being driven

by a certain Zacarias Payba at the time

of the accident. The unit was a total

wreck was returned.

On March 20, 1980, DBP released the

proceeds of private respondents

motorcycle loan to Norkis in the total

sum of P7,500. As the price of the

motorcycle later increased to P7,828 in

March, 1980, Nepales paid the

difference of P328 and demanded the

delivery of the motorcycle. When Norkis

could not deliver, he filed an action for

specific performance with damages

against Norkis in the RTC of Negros

Occidental. He alleged that Norkis failed

to deliver the motorcycle which he

purchased,

thereby

causing

him

damages. Norkis answered that the

motorcycle had already been delivered

to private respondent before the

accident, hence, the risk of loss or

damage had to be borne by him as

owner of the unit.

ISSUE:

Whether or not there has been a

transfer of ownership of the motorcycle

to Alberto Nepales.

HELD:

No.The issuance of a sales invoice does

not prove transfer of ownership of the

thing sold to the buyer. An invoice is

nothing more than a detailed statement

of the nature, quantity and cost of the

thing sold and has been considered not

a bill of sale. In all forms of delivery, it is

necessary that the act of delivery

whether constructive or actual, be

coupled with the intention of delivering

the thing. The act, without the intention,

is insufficient. When the motorcycle was

registered by Norkis in the name of

private respondent, Norkis did not intend

yet to transfer the title or ownership to

Nepales, but only to facilitate the

execution of a chattel mortgage in favor

of the DBP for the release of the buyers

motorcycle loan.

Article 1496 of the Civil Code which

provides that in the absence of an

express assumption of risk by the buyer,

the things sold remain at sellers risk

until the ownership thereof is transferred

to the buyer, is applicable to this case,

for there was neither an actual nor

constructive delivery of the thing sold,

hence, the risk of loss should be borne

by the seller, Norkis, which was still the

owner and possessor of the motorcycle

when it was wrecked. This is in

accordance with the well known

doctrine of res perit domino.

Philippine Suburban Dev. Corp. vs The

Auditor General

Facts

The President of the Philippines and the

Cabinet had a meeting about the relocation

of the squatters of Manila and suburbs.

o They then eventually approved in

principle the acquisition by the Peoples

Homesite and Housing Corporation

(PHHC) of the unoaccupied portion of

the Sapang Palay Estate in Sta. Maria

Bulacan for relocating the squatters

who desire to settle north of Manila,

and of another area either in Las Pinas

or Paranaque, Rizal, or Bacoor for

those who desire to settle south of

Manila

o The project was to be financed through

the flotation of bonds under the charter

of the PHHC in the amount of Php 4.5

million, the same to be absorbed by the

GSIS

o PHHC was informed abut this approval

o PHHC Board of Directors then passed

a Resolution authorizing the purchase

of the unoccupied portion of the

Sapang Palay Estate at Php 0.45 per

square meter subject to the following

conditions precedent:

President

shall

confirm

the

purchase price

Portion of the estate to be

acquired shall first be defined

The President shall first provide

the PHHC with the necessary

funds to effect the purchase and

development of this property

That the contract of sale shall first

be approved by the Auditor

General

That the vendor shall agree to the

dismissal with prejudice of a

pending Civil Case

o The President subsequently authorized

the floating of bonds to be absorbed by

the GSIS, in order to finance the

acquisition by the PHHC of the entire

Sapang Palay Estate at a price not to

exceed Php 0.45 per square meter.

o PHHC then acquired possession of the

property, with the consent of Phil.

Suburban, to enable PHHC to proceed

immediately with the construction of

roads in the new settlement and to

resettle the squatters and flood victims

in Manila who were rendered homeless

by the floods or ejected from the lots

which they were occupying.

o Philippine

Suburban

Development

Corporation (owner of the unoccupied

portion of Sapang Palay) and PHHC

entered into a contract embodied in a

public instrument entitled Deed of

Absolute Sale whereby the former

conveyed unto the latter the two

parcels of land.

The document was not registered

in the Office of the Register of

Deeds until March 14, 1961, due

to the fact, as petitioner claims,

that the PHHC could not at once

advance the money needed for

registration expenses.

o On the other hand, the Auditor General

expressed objections and requested a

reexamination of the contract in view of

the fact that the value of the hacienda

greatly increased. This objection was

communicated to the President.

o The President, however, still approved

the Deed of Absolute Sale.

Provincial Treasurer of Bulacan requested

PHHC to withhold a specific amount from

the purchase price to be paid by it to the

Philippine

Suburban.

Said

amount

represented the realty tax due on the

property involved.

o PHHC paid under protest. It then

requested the Secretary of Finance to

order a refund of the amount on the

argument that it ceased to be the

owner of the land in question upon the

execution of the Deed of Aboslute Sale

and that the possession of the property

was actually delivered to the vendee

prior to the sale. Secretary of Finance

denied the request.

Respondent argues, on the other hand, that:

o Art. 1498 does not apply because of

the requirement in the contrct that the

sale shall first be approved by the

Auditor General

o that the petitioner should register the

deed and secure a new title in the

name of the vendee before the

government can be compelled to pay

the balance of the purchase price

o that according to the Land Registration

Act, until the deed of sale has been

actually registered, the vendor remains

as the owner of the said property, and

therefore, liable for the payment of real

property tax

Issues:

1. WON the approval of the Auditor General is

still needed No

2. WON there was delivery of the property to

the vendee Yes

3. WON the payment of the real estate tax shall

be paid by the purchaser - Yes

Ratio

1. The approval of the sale by the Auditor

General is no longer needed in the case at bar

since the contract has been entered into for a

special purpose and that it was entered into to

implement the Presidential directive.

The approval required by Administrative

Order 290 only refers to contracts in

general,

ordinarily

etered

into

by

government offices and GOCCs

2. There is delivery of the property

General rule: there is symbolic delivery of

the property subject of the sale by the

execution of the public instrument, unless

from the express terms of the instrument, or

by clear inference therefrom, this was not

the intention of the parties

o Exmples when symbolic delivery is not

intended

When a certain date is fixed for the

purchaser to take possession of

the property subject of the

conveyance

In case of sale by installments, it is

stipulated that until the last

installment is made, it is stipulated

that until the last installment is

made, the title to the property

should remain with the vendor

When the vendor reserves the

right to use and enjoy the property

until the gathering of the pending

crops, or where the vendor has no

control over the thing sold at the

moment of the sale

In the case at bar, the vendor had actually

placed the vendee in possession and

control over the thing sold, even before the

date of the sale. The condition that

petitioner should first register the deed of

sale is not necessary for the validity of the

sale.

3. After delivery of possession, purchaser shall

be liale for the taxes

Since the delivery of possession, coupled

with the execution of the Deed of Absolute

Sale had consummated the sale and

transferred the title to the purchaser, the

payment of the real estate tax after such

transfer is the responsibility of the

purchaser.

However, in the case at bar, the purchaser

PHHC is a government entity not subject to real

property ta

Addison vs. Felix

Facts:

By a public instrument dated June 11, 1914,

Addison sold to Marciana Felix four parcels of

land. Felix paid, at the time of the execution of

the deed, P3,000 and bound herself to pay the

remainder in installments. In January 1915,

plaintiff filed a suit to compel the defendant to

make payment of the final installment. The

defendant contends that the plaintiff had

absolutely failed to deliver to the former the

lands that were the subject matter of the sale,

November 10, 1903, (Civ. Rep., vol. 96, p. 560)

that this article "merely declares that when the

sale is made through the means of a public

instrument, the execution of this latter is

equivalent to the delivery of the thing sold:

which does not and cannot mean that this

fictitious tradition necessarily implies the real

tradition of the thing sold, for it is

incontrovertible that, while its ownership still

pertains to the vendor (and with greater reason

if it does not), a third person may be in

possession of the same thing; wherefore,

though, as a general rule, he who purchases by

means of a public instrument should be

deemed . . . to be the possessor in fact, yet this

presumption gives way before proof to the

contrary."

notwithstanding the demands made upon him.

Also, the plaintiff was only able to designate

only 2 of the 4 parcels and more than 2/3 of

these two were found to be in possession of

one Juan Villafuerte. The trial court rendered

judgment holding the contract of sale to be

rescinded. Hence, this appeal.

Issue:

Whether or not the lands were delivered.

Held:

No. The records show that the plaintiff did not

deliver the thing sold. It is true that the

execution of a public instrument is equivalent to

the delivery of the thing which is the object of

the contract, but, in order that this symbolic

delivery may produce the effect of tradition, it is

necessary that the vendor shall have had such

control over the thing sold, that at the moment

of the sale, its material delivery could have

been made. It is not enough to confer upon the

purchaser the ownership and the right of

possession. The thing sold must be placed in

his control.

The supreme court of Spain, interpreting article

1462 of the Civil Code, held in its decision of

It is evident, then, in the case at bar, that the

mere execution of the instrument was not a

fulfillment of the vendors' obligation to deliver

the thing sold, and that from such nonfulfillment arises the purchaser's right to

demand, as she has demanded, the rescission

of the sale and the return of the price. (Civ.

Code, arts. 1506 and 1124.)

Of course if the sale had been made under the

express agreement of imposing upon the

purchaser the obligation to take the necessary

steps to obtain the material possession of the

thing sold, and it were proven that she knew

that the thing was in the possession of a third

person claiming to have property rights therein,

such agreement would be perfectly valid. But

there is nothing in the instrument which would

indicate, even implicitly, that such was the

agreement. It is true, as the appellant argues,

that the obligation was incumbent upon the

defendant Marciana Felix to apply for and

obtain the registration of the land in the new

registry of property; but from this it cannot be

concluded that she had to await the final

decision of the Court of Land Registration, in

order to be able to enjoy the property sold. On

the contrary, it was expressly stipulated in the

contract that the purchaser should deliver to the

vendor one-fourth "of the products ... of the

aforesaid four parcels from the moment when

she takes possession of them until the Torrens

certificate of title be issued in her favor." This

obviously shows that it was not forseen that the

purchaser might be deprived of her possession

during the course of the registration

proceedings, but that the transaction rested on

the assumption that she was to have, during

said period, the material possession and

enjoyment of the four parcels of land.

Inasmuch as the rescission is made by virtue of

the provisions of law and not by contractual

agreement, it is not the conventional but the

legal interest that is demandable.

It is therefore held that the contract of purchase

and sale entered into by and between the

plaintiff and the defendant on June 11, 1914, is

rescinded, and the plaintiff is ordered to make

restitution of the sum of P3,000 received by him

on account of the price of the sale, together

with interest thereon at the legal rate of 6 per

annum from the date of the filing of the

complaint until payment, with the costs of both

instances against the appellant. So ordered.

TEN FORTY REALTY V. CRUZ|

PanganibanG.R. No. 151212 | September

10, 2003

FACTS:

Petitioner filed an ejectment complaint against

Marina Cruz(respondent) before the MTC.

Petitioner alleges that the land indispute was

purchased from Barbara Galino on December

1996, andthat said land was again sold to

respondent on April 1998;

On the other hand, respondent answer with

counterclaim that never was there an occasion

when petitioner occupied a portion of the

premises. In addition, respondent alleges that

said land was a public land (respondent filed a

miscellaneous sales application with the

Community Environment and Natural

Resources Office) and the action for ejectment

cannot succeed where it appears that

respondent had been in possession of the

property prior to the petitioner;

On October 2000, MTC ordered respondent to

vacate the land and surrender to petitioner

possession thereof. On appeal, the RTC

reversed the decision. CA sustained the trial

courts decision.

ISSUE/S:

Whether or not petitioner should be declared

the rightful owner of the property.

HELD:

No. Respondent is the true owner of the land.1)

The action filed by the petitioner, which was an

action for unlawful detainer, is improper. As

the bare allegation of petitioners tolerance of

respondents occupation of the premises has

not been proven, the possession should be

deemed illegal from the beginning. Thus, the

CA correctly ruled that the ejectment case

should have been for forcible entry. However,

the action had already prescribed because the

complaint was filed on May 12, 1999 a month

after the last day forfiling;2) The subject

property had not been delivered to petitioner;

hence, it did not acquire possession either

materially or symbolically. As between the two

buyers, therefore, respondent was first in actual

possession of the property.

As regards the question of whether there was

good faith in the second buyer. Petitioner has

not proven that respondent was aware that her

mode of acquiring the property was defective at

the time she acquired it from Galino. At the

time, the property which was public land

had not been registered in the name of Galino;

thus, respondent relied on the tax declarations

thereon. As shown, the formers name

appeared on the tax declarations for the

property until its sale to the latter in 1998.

Galino was in fact occupying the realty when

respondent took over possession. Thus, there

was no circumstance that could have placed

the latter upon inquiry or required her to further

investigate petitioners right of ownership.

DOCTRINE/S:

Execution of Deed of Sale; Not sufficient as

delivery. Ownership is transferred not by

contract but by tradition or delivery. Nowhere in

the Civil Code is it provided that the execution

of a Deed of Sale is a conclusive presumption

of delivery of possession of a piece of real

estate. The execution of a public instrument

gives rise only to a prima facie presumption of

delivery. Such presumption is destroyed when

the delivery is not effected, because of a legal

impediment. Such constructive or symbolic

delivery, being merely presumptive, was

deemed negated by the failure of the vendee to

take actual possession of the land sold.

Disqualification from Ownership of Alienable

Public Land.

Private corporations are disqualified from

acquiring lands of the public domain, as

provided under Section 3 of Article XII of the

Constitution. While corporations cannot acquire

land of the public domain, they can however

acquire private land. However, petitioner has

not presented proof that, at the time it

purchased the property from Galino, the

property had ceased to be of the public domain

and was already private land. The established

rule is that alienable and disposable land of the

public domain held and occupied by a

possessor personally or through

predecessors-in-interest, openly, continuously,

and exclusively for 30 years is ipso jure

converted to private property by the mere lapse

of time.

RULING:

The Supreme Court DENIED the petition.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Busmente Comm 1Dokumen91 halamanBusmente Comm 1Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Section One-Parricide, Murder, Homicide: Title Eight Crimes Against PersonsDokumen2 halamanSection One-Parricide, Murder, Homicide: Title Eight Crimes Against PersonsAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Cheat Sheet (Requisites and Elements)Dokumen2 halamanCheat Sheet (Requisites and Elements)Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- 37 (Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Smart Communication, Inc.Dokumen1 halaman37 (Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Smart Communication, Inc.Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Industrial PropertyDokumen40 halamanUnderstanding Industrial PropertyAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Cheat Sheet (Requisites and Elements)Dokumen2 halamanCheat Sheet (Requisites and Elements)Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Crim Rev Book Two Week 3'Dokumen37 halamanCrim Rev Book Two Week 3'Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Torts Prox 3Dokumen122 halamanTorts Prox 3Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Customs Modernization (Customtrade - Asia)Dokumen7 halamanCustoms Modernization (Customtrade - Asia)Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Admin Vi ViiiDokumen106 halamanAdmin Vi ViiiAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- TRT WPPT 001enDokumen13 halamanTRT WPPT 001enAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Amsterdam 2 Days Itinerary Easy GoingDokumen11 halamanAmsterdam 2 Days Itinerary Easy GoingAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Maritime NotesDokumen13 halamanMaritime NotesAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Admin 1aDokumen80 halamanAdmin 1aAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Cases 212Dokumen87 halamanCases 212Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Evid 128Dokumen95 halamanEvid 128Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- ADMIN 1aaDokumen125 halamanADMIN 1aaAriel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- Cases 1Dokumen184 halamanCases 1Ariel Mark PilotinBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- PDEA ComicsDokumen16 halamanPDEA ComicsElla Chio Salud-MatabalaoBelum ada peringkat

- 25 ConstituencyWiseDetailedResultDokumen197 halaman25 ConstituencyWiseDetailedResultdeepa.haas5544Belum ada peringkat

- Downloadable Diary February 27thDokumen62 halamanDownloadable Diary February 27thflorencekari78Belum ada peringkat

- Law of Evidence: An Overview On Different Kinds of Evidence: by Shriya SehgalDokumen7 halamanLaw of Evidence: An Overview On Different Kinds of Evidence: by Shriya SehgalZarina BanooBelum ada peringkat

- Declaratory DecreesDokumen5 halamanDeclaratory DecreesNadeem Khan100% (1)

- Contract Termination AgreementDokumen3 halamanContract Termination AgreementMohamed El Abany0% (1)

- Age of Hazrat Ayesha (Ra) at The Time of MarriageDokumen6 halamanAge of Hazrat Ayesha (Ra) at The Time of MarriageadilBelum ada peringkat

- A 276201811585264Dokumen79 halamanA 276201811585264Nilesh TapdiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Vham-Bai 3-The Gift of The MagiDokumen20 halamanVham-Bai 3-The Gift of The MagiLý Thị Thanh ThủyBelum ada peringkat

- History of IlokanoDokumen8 halamanHistory of IlokanoZoilo Grente Telagen100% (3)

- Handbook For Coordinating GBV in Emergencies Fin.01Dokumen324 halamanHandbook For Coordinating GBV in Emergencies Fin.01Hayder T. RasheedBelum ada peringkat

- Spending in The Way of Allah.Dokumen82 halamanSpending in The Way of Allah.Muhammad HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Persons and Family Relations: San Beda College of LawDokumen3 halamanPersons and Family Relations: San Beda College of LawstrgrlBelum ada peringkat

- Flow Chart On Russian Revolution-Criteria and RubricDokumen2 halamanFlow Chart On Russian Revolution-Criteria and Rubricapi-96672078100% (1)

- The Role of Counsel On Watching Brief in Criminal Prosecutions in UgandaDokumen8 halamanThe Role of Counsel On Watching Brief in Criminal Prosecutions in UgandaDavid BakibingaBelum ada peringkat

- Cr.P.C. Case LawsDokumen49 halamanCr.P.C. Case LawsHimanshu MahajanBelum ada peringkat

- Miss: Date: Student S Name: Form: Time: - Min. Learning Outcome: To Reinforce Main Ideas, Characters Information From The Book "Dan in London "Dokumen2 halamanMiss: Date: Student S Name: Form: Time: - Min. Learning Outcome: To Reinforce Main Ideas, Characters Information From The Book "Dan in London "Estefany MilancaBelum ada peringkat

- Anthony Kaferle, Joe Brandstetter, John Kristoff and Mike Kristoff v. Stephen Fredrick, John Kosor and C. & F. Coal Company. C. & F. Coal Company, 360 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1966)Dokumen5 halamanAnthony Kaferle, Joe Brandstetter, John Kristoff and Mike Kristoff v. Stephen Fredrick, John Kosor and C. & F. Coal Company. C. & F. Coal Company, 360 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Memorial For The AppellantDokumen26 halamanMemorial For The AppellantRobin VincentBelum ada peringkat

- National Civil Rights Groups Sue Louisiana Judges, Sheriff Over Unconstitutional Bail SystemDokumen35 halamanNational Civil Rights Groups Sue Louisiana Judges, Sheriff Over Unconstitutional Bail SystemAdvancement ProjectBelum ada peringkat

- Income Tax (Deduction For Expenses in Relation To Secretarial Fee and Tax Filing Fee) Rules 2014 (P.U. (A) 336-2014)Dokumen1 halamanIncome Tax (Deduction For Expenses in Relation To Secretarial Fee and Tax Filing Fee) Rules 2014 (P.U. (A) 336-2014)Teh Chu LeongBelum ada peringkat

- RESIGNATIONDokumen1 halamanRESIGNATIONAlejo B. de RosalesBelum ada peringkat

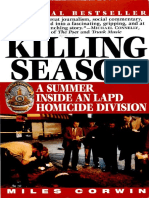

- Pub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd HomicidDokumen356 halamanPub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd Homiciddragan kostovBelum ada peringkat

- Course: Advanced Network Security & Monitoring: Session 5Dokumen18 halamanCourse: Advanced Network Security & Monitoring: Session 5Sajjad AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- The Menstrual CycleDokumen14 halamanThe Menstrual Cycleapi-383924091% (11)

- Who Christ WasDokumen2 halamanWho Christ Waswillisd2Belum ada peringkat

- Section 19 of HMA ActDokumen2 halamanSection 19 of HMA ActNandini SaikiaBelum ada peringkat

- The Escalating Cost of Ransomware Hubert YoshidaDokumen3 halamanThe Escalating Cost of Ransomware Hubert YoshidaAtthulaiBelum ada peringkat

- Romans Bible Study 32: Christian Liberty 2 - Romans 14:14-23Dokumen4 halamanRomans Bible Study 32: Christian Liberty 2 - Romans 14:14-23Kevin MatthewsBelum ada peringkat

- UFOs, Aliens, and Ex-Intelligence Agents - Who's Fooling Whom - PDFDokumen86 halamanUFOs, Aliens, and Ex-Intelligence Agents - Who's Fooling Whom - PDFCarlos Eneas100% (2)