JSI Sticks and Stone Sept 2015

Diunggah oleh

Eka Wahyudi NggoheleHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

JSI Sticks and Stone Sept 2015

Diunggah oleh

Eka Wahyudi NggoheleHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Sticks and stones: How words and

language

impact

upon

social

inclusion

___________________________________________

Kathy McKay

School of Health

University of New England, Armidale

Stuart Wark

School of Rural Medicine

University of New England, Armidale

Virginia Mapedzahama

CRN for Mental Health and Well-Being in Rural and Regional Communities

University of New England, Armidale

School of Social Sciences and Psychology

University of Western Sydney

Tinashe Dune

CRN for Mental Health and Well-Being in Rural and Regional Communities

University of New England, Armidale

School of Science and Health

University of Western Sydney

Saifur Rahman

School of Rural Medicine

University of New England, Armidale

Journal of Social inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Catherine MacPhail

School of Health

University of New England, Armidale

Abstract

Language framed as derogatory names and symbols can have implications for

people and their life experiences. Within a Saussurian-inspired frame, and looking at

ideas of stigma and social inclusion, this paper examines the use of language as a

weapon within a social context of (changing) intent and meaning. Three examples of

language use in mainstream society are analysed: retarded which evolved from

scientific diagnosis to insult; gay as a derogatory adjective within popular culture;

and, the way language around suicide is used to both trivialise and stigmatise those

who are suicidal, as well as those who are bereaved.

Key words: Social inclusion, derogatory, stigma, retarded, gay, suicide

Introduction

Lisa: A Rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

Bart: Not if you called 'em Stenchblossoms.

Homer: Or Crapweeds.

Marge: I'd sure hate to get a dozen Crapweeds for Valentine's Day. I'd rather have

candy.

Homer: Not if they were called Scumdrops.

The Principal and the Pauper, The Simpsons, 1997, Season 9, Episode 180

The ability to use language, and to assign names to things, has traditionally been

considered a gift in Western linguistic and philosophical traditions (Harris, 1990).

However, de Saussure (1910-1911) argued that words do more than name, they

assign meaning and symbolism to the named things (Culler, 1976; Harris, 1987;

Hurford, 1989). Words are not empty vessels linked together to create conversation;

147

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

rather they carry vital information between speaker(s) and listener(s) outside of the

basic information conveyed. Indeed, choice of words conveys meaning far beyond

that of the words themselves; choice of language tells the listener about the

speakers lived experience and how they see the world (Devitt & Sterelny, 1999;

Garrett & Baquedano-Lopez, 2002). Words do not have singular or static meanings

and, consequently, it becomes vital to recognise the speakers intent when words are

used that may have both positive and negative meanings; there are literal definitions

to dissect, as well as any underlying secondary messages (Garrett & BaquedanoLopez, 2002). Critical discourse analysis is a process of examining how inherent, but

often unrecognised, power relationships are associated with language usage and the

choice of specific words. It attempts to uncover the hidden, implied and unconscious

social constructs that are both developed and reinforced through the choice of words

and language, and through this, seeks to recognise and highlight social inequities

that language use can both promote and maintain (Forchtner, 2012; Gee, 2014).

Confusion and offense can arise when technically correct words that describe

certain conditions or situations are subsequently misappropriated into general dayto-day usage with modified meanings. Keely and Fink (2011) commented that

subsequent generations will often view potentially offensive words more liberally than

the previous one. Examples of these changing denotations include words such as

retarded or gay, and phrases referring to actions including suicide such as I just

wanted to kill myself. Such words and phrases are used in daily communication

often with no thought about their relevance to the literal meaning, or the potential

emotional impact that their usage may have upon other individuals. The meanings

signified with these words become lost in dismissive usage, leaving listeners hurt by

seemingly callous language, or else the meanings act as weapons in language

usage intended to hurt.

With respect to critical discourse analysis, it is important to differentiate

between the concept of hate speak, which is a deliberate act of discrimination

designed to denigrate an individual or group (e.g. Butler, 1997; Delgado & Stefancic,

2004; Leets, 2002), and a more subtle and yet still harmful indirect action.

Worldwide, there is considerable discussion around the need to monitor and even

legislate against hate speak and hate crimes (Bleich, 2011), however, the casual use

of formerly derogatory terms can get overlooked. This article examines the way in

which language is used to change a persons experience into something generally

148

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

and definitely negative and the implications when tragedy is trivialised without

thought for the consequences. As both language, and those who use it, are social

creatures and products, the words and phrases examined in this article have been

placed within a social context and the analysis framed around (changing) intent and

meaning. Here, three examples will be analysed. The first is the evolution of the

word retarded from scientific diagnosis to casual insult. The second is the use of the

word gay as a derogatory adjective within mainstream popular culture. The third is

the way in which language around suicide is used which both trivialises and

stigmatises those who are suicidal, as well as those who are bereaved.

Retarded

When Australia was colonised by the English in 1788, the first Governor Phillip was

bestowed with the power to deal with, as he saw fit, people classified as idiots

(Shea, 1999). Over time, the words used to define and describe people with an

intellectual impairment have changed around the world. Generally, the term

intellectual disability is used to describe an individual whose intellectual capacity is

significantly lower than that of their typical counterparts (World Health Organisation,

2012). Other terms for intellectual disability include mental retardation, mental

handicap, mental impairment, learning disability and developmental disability.

Previously commonplace terms such as idiot, subnormal, handicapped, moron,

imbecile and feeble minded are now largely and globally technically obsolete due

to the negative connotations and implications associated with them (Lewis & Kellett,

2004). For instance, in Australia intellectual disability has long replaced mental

retardation within both research and wider public usage because of the negativity

associated with the term retarded.

Until May 2013, the term mental retardation was still used in the United

States of America (USA) in certain circles as it remained the definition in the current

version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR (APA,

2000). DSM-V, which was released in May 2013, has officially changed the

diagnostic term mental retardation to intellectual disability, thereby bringing the

DSM into alignment with contemporary terminology used within other health

disciplines (APA, 2013). As an example of this movement away from using the term

retarded, in 2009 the American Journal on Mental Retardation officially changed its

149

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

name to the American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. The

editor noted that:

in part, the change has been motivated by a desire to avoid the negative

connotations that have come to be associated with the term mental

retardation. I fully endorse this change in terminology because it reflects our

field's commitment not only to our science but to the people whose lives we

hope to improve through our efforts. Quite simply, the change in terminology

is a tangible sign of our respect for, and solidarity with, people who have

disabilities and their families (Abbeduto, 2009, p. 1).

Similarly, in 2010 US President Obama signed off on the Bill S. 2781 which

officially removed the terms mental retardation and mentally retarded from all

government policies, replacing them instead with the term intellectual disability (US

Congress, 2012). However, while this change is taking place in academic and

political circles, words such as retarded are being increasingly used in mainstream

media and social networking platforms to describe the actions of people without any

intellectual impairment (R-Word, 2012a).

For example, the movie Tropic Thunder had numerous characters refer to

activities or actions as moronical or retarded. It spawned the phrase going the full

retard which has entered the vernacular to describe an action that is completely

ridiculous and totally lacking in value (e.g. Urban Dictionary, 2009). This tacit

promotion of the word retard within a popular movie has seen it quickly enter

mainstream use. Siperstein, Pociask and Collins (2010) reported that 92% of 1,169

Americans between the ages of 8 and 18 had either used or heard someone else

use the word retarded in daily speak. Indeed, in the 2012 US presidential debates

Barack Obama was described as a retard by political pundit Ann Coulter (CNN,

2012). When it was suggested to her that using this word was potentially offensive,

she defended her use of retard and provided a generic response of screw them to

everyone who had complained (Lengell, 2012). This pejorative definition of the word

retardation is now colloquially synonymous with sheer stupidity, incapability,

worthlessness and valueless. The unfortunate side-effect of this change is that it

further reinforces a stereotype of an individual with an intellectual disability as being

a lesser member of the community. The Special Olympics movement started the

150

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Spread the Word to End the Word as a means of trying to raise community

awareness about the dehumanizing and hurtful effects of the word retard(ed) and

encourage people to pledge to stop using the R-word (R-Word, 2012b, on-line).

The power of words cannot be underestimated. Zimbardo (2008) describes

how the process of using words can dehumanise people through language, and that

this is the starting point for social exclusion and potentially a stepping stone towards

more serious actions. People with intellectual disabilities have long faced both overt

and subtle discrimination and social exclusion (Hall, 2005). For example, the

eugenics movement initially argued that people with intellectual disabilities were

moronic or feebleminded and therefore inferior and undeserving of life (Dune,

2012). This concept culminated in widespread sterilization practices around the

world that continued throughout the twentieth Century (Block, 2000) and the mass

murder in Nazi Germany of tens of thousands of people with disabilities (Mostert,

2002). While there has been significant social and political change regarding

individuals rights in the past decades (e.g. United Nations General Assembly, 2006),

there remains an undercurrent of discrimination and social exclusion for associated

with people with intellectual disability across living environments, age and access to

health support services (Ali et al., 2013; Nicholson & Cooper 2013; Wark, Hussain, &

Edwards, 2014). While words like retarded remain in common usage as a

derogatory term, this underlying discrimination and associated implication of

worthlessness will remain difficult to reduce.

Gay

The concept and meaning of the word gay has changed significantly over the last

five centuries. For instance, in 1637 the word gay described a state of immortality

(Online Etymology Dictionary, 2013). By the late seventeenth century the term

referred to the state of being addicted to pleasures (Warner, 2012). This assumed

that the individual was hedonistic, carefree and minimally concerned with moral

constraints. While these connotations of gay seem to relay a sense of happiness and

freedom, they came with social judgment. For example, the word gay was used for

female sex workers (gay woman), a womaniser (gay man) or a brothel (gay house)

(Online Etymology Dictionary, 2013).

By the early twentieth century gay was less of a social faux-pas as men and

women who decided to remain single were associated with the concept. An example

151

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

of this changing usage can be seen in the title of the book and film The Gay Falcon

(1941) which features a womanising detective named Gay. This use of the word

continued well into the mid-twentieth century where middle-aged bachelors could be

described as gay which simply indicated that he was unattached and free. This

usage also applied to women with free-wheeling lifestyles and numerous male

friends. The British comic strip Jane, first published in the 1930s, presented the

adventures of Jane Gay (a play on the name Lady Jane Gray), a socially and

sexually free woman. Far from implying homosexuality, these examples are amongst

many of their time in which being gay referred to the envious state of being

unattached and the sexual freedom that comes with being single (Urban Dictionary,

2013).

Following post-war social reform and Western societies moving back towards

more conservative positions in the twentieth century the word gay began to be

associated more explicitly with sexual deviancy. As such, its use to exclusively mean

homosexual was not necessarily farfetched. Western countries during this time

were predominantly patriarchal. Men were expected to be highly masculine

breadwinners and predominantly filled all the politically and economically powerful

positions (Hollows, 2002). As such, those men who did not meet their perceived duty

of marriage and maintaining, dressing or even acting in accordance with societal

expectations of a man were assumed to be homosexual (Connell, 1992).

By 1952 homosexuality was formally pathologised as a sociopathic

personality disturbance (APA, 1952) and was deemed illegal on most continents.

Subsequently, the word gay not only meant someone who went against common

societal expectations but also an individual (most often a man) who was mentally ill

and criminally inclined. Coming into the twenty first century, and in-line with

international Gay Pride movements, the term gay no longer denotes mental illness

or criminality. However, the word has retained it connection to homosexuals

(particularly gay men) and its relation to social and sexual deviance (Warner, 2012).

In this timeframe, the word has also attained additional meaning amongst youth and

within popular culture.

In contemporary youth and popular culture the word, is often used in derisive

spirit (Sherwin, 2006). In this case the word gay is used pejoratively and

disparagingly towards an individual (e.g. youre so gay) and/or an activity (e.g. that

activity was really gay). Considering this context the word gay has come to mean

152

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

lame, rubbish, useless or worthless. This pejorative usage has its origins in the

late 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s and especially in the late 1990s, the usage as a

generic insult became common among young people (Winterman, 2008).

While it may seem that the use of the word gay has been accepted within

contemporary Western culture media representatives and music artists recognise the

homophobic nature when used in this way:

If I was gay, I would think hip-hop hates me.

Have you read the YouTube comments lately?

Man, thats gay gets dropped on the daily

We become so numb to what were saying (Macklemore, 2012).

While some may defend the usage of the word gay in popular media

(Sherwin, 2006), it is more readily being recognised as a manifestation of

homophobic abuse (Grew, 2007a). For instance, the Minister for Children in the

United Kingdom, Kevin Brennan, stated in response to the casual use of

homophobic language by mainstream radio DJs:

too often seen as harmless banter instead of the offensive insult that it really

represents. ... To ignore this problem is to collude in it. The blind eye to casual

name-calling, looking the other way because it is the easy option, is simply

intolerable (Grew, 2007b, online).

While the current use of the word gay is being acknowledged as homophobic

and derogatory its use remains pervasive and detrimental. As with the word

retarded, the emerged usage of gay to imply worthlessness has created an

impediment to the societal acceptance of individual difference.

Suicide

The construction of suicide threats and attempts has tended to be labelled attentionseeking or manipulative; not to be taken seriously (Canetto, 1997; Canetto & Lester,

1998; Lester, 1996). Survival is perversely perceived as failure; threats become

throw-away words, something said by one person (usually constructed as female) to

scare another into changing their behaviour or decision. In this way, words around

suicide have been seen to be framed around selfish desire, almost a childishness

153

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

that demonstrates a grabbing want rather than a considered need. The fear

attached to such a threat speaks to the guilt and shame that remain bound to

suicide; the stigma that still stains the death (Cvinar, 2005; Minois, 1999; Sudak,

Maxim, & Carpenter, 2008).

However, language around suicide has shifted in more recent popular culture.

There is less a sense of the suicidal person being manipulative, rather that a suicidal

act should be performed in atonement for not fulfilling the needs of the other. In

2007, Timbaland, one of Americas top hip-hop artists and producers, released a

song called Kill Yourself. A portion of its lyrics are as follows:

Go on ahead

Kill yourself, kill yourself, kill yourself

Go on, kill yourself, kill yourself, kill yourself

If I was you, I wouldn't feel myself.

If you still wanna hang

We'll come to get ya

Put the rope around your neck and jump, my nigga! (Timbaland, 2007)

In a genre well-criticised for its use of language around women and violence,

little has been said about this chorus seemingly goading someone to suicide. It must

be noted that this song didnt appear on a little-known album but one that made

significant sales around the world (Sanneh, 2007; Van Gelder, 2007). Indeed, it is

not just hip-hop that has incorporated throw-away lines taunting someone to suicide.

Katy Perrys album One of the Boys sold five million copies (RC, 2010) and includes

the following lyrics from the song Ur So Gay:

I hope you hang yourself with your H&M scarf

While jacking off listening to Mozart (Perry, 2008).

While this song has been roundly criticised for its homophobic narrative, in

line with Macklemores plea in the previously mentioned song Same Love, its

introductory lines wish for someone elses (auto-erotic) suicide.

Indeed, language around suicide has long been difficult. In 2012, Beaton,

Forster and Maple wrote about the difficulties still attached to describing suicide both

in the media and academic world. Specifically focusing on the verb commit, they

154

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

deconstructed the phrase commit suicide in terms of its historical and legal

constructs, as well as its meaning when someone has experienced suicidal

behaviours or bereavement. They concluded that:

Using the word commit within the context of suicide is not only unnecessary,

it is also harmful. such talk is often stuck in concepts from the past that

perpetuate stigma, constrain thinking and reduce help-seeking behaviour.

Those bereaved by suicide and those who have been suicidal themselves

have commented on the negative and unhelpful effects of stigmatizing

language (Beaton et al., 2012, pg. 731).

The way people feel that their experiences are perceived and articulated by

others can greatly impact on their recovery (Maple et al., 2010; Sommer-Rotenberg,

1998). This reflects Saussurian beliefs around language; the way others talk about

suicide not only reflects the emotionally and ethically loaded meanings attached to

the words around suicide but also the speakers lived experiences of suicidality,

which can then negatively impact on the lived experience of the bereaved.

However, this is not to say that jokes are not, and cannot, be made about

suicide. In a recent article, Lester explored the humour around suicide and the

potential offense connected to them. Interestingly, in an academic journal called

Death Studies, Lester still felt he had to justify the inclusion of some jokes by saying:

The fact is that there are books, cartoons, and jokes about suicide, and it is a

worthwhile task to examine them and analyze them. I faced a dilemma,

therefore, as to whether to include examples in this article, because to do so

may offend some readers. However, as is common in many work settings

where the stress level is high, there is a lot of joking among the staff who work

with people in crises, often around suicide and the suicidal clients. Therefore,

I decided to include some examples of this type of humor (Lester, 2012, pg.

664).

While an esteemed academic struggled with language and inclusion that was

potentially problematised, if taken out of its specific context, this same reflection has

not seemingly occurred with Timbalands or Perrys song lyrics. Lester starts from

the point of suicide as a tragedy and finds that humour is one way for people for deal

155

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

with such difficult issues as pain, loss and grief. On the other hand, the

aforementioned song lyrics also posit suicide as a terrible event but one that you

wish upon someone you want punished, whether this punishment is for a lack of

respect (Timbaland) or a difficult relationship (Perry). The language around suicide is

used as a weapon to hurt others.

Yet, the problem here lies with how this weapon is used by people in and out

of popular culture. Go on, kill yourself is not just a song lyric but a comment all too

commonly made in response to different posts on YouTube and other internet

forums. Recently, many young people have started making videos using flashcards

to tell their stories of abuse, depression and self-harm. While many comments have

been supportive, others have taunted. Some of these young video-makers have

survived their difficult periods, and have made more inspirational videos (see Jonah

Mowry); others have suicided (see Amanda Todd). The liminal space in which these

vulnerable young people exist make the compassionate use of language all the more

important.

Indeed, it is important to reflect upon the consequences of throw-away

language connected to suicide, whether articulated as taunt or threat. Even when

language is simply used to express an extremity of emotion Going to that class

makes me want to jump off a cliff, That dress is so amazing, Ill kill myself if they

dont have it in my size there is a presumption attached that deserves to be

unpacked. Within the stigma surrounding suicide, the idea still appears to linger that

a person seeking death will do so in secret, they will not tell anyone their intention.

Silence seems to only strengthen the perception that death must be the intention. On

the other hand, the intentions of those who speak openly about their suicidality, who

are perceived to threaten, are viewed, to paraphrase Shakespeare, to signify

nothing (Canetto, 1997; Lester, 1996). This manipulation is only heightened in such

throwaway language. Suiciding over a dress may indeed appear to be nonsensical

when said outside any context; however, when placed within experiences of trauma,

psychache, or chronic mental illness, the words become altogether different. The

importance is then: how to tell the difference between throwaway language and

words of intention? Again, the language we use, the ways in which we talk about

suicide, needs to be better understood in terms of compassion and awareness.

156

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Conclusion

The words we use are the primary symbolic medium through which cultural

knowledge is communicated and instantiated, negotiated and contested, reproduced

and transformed (Garrett & Baquedano-Lopez, 2002, pg. 339). However, just as

cultural knowledge is dynamic, so is the language through which it is conveyed.

While the meanings of the words retard and gay have changed throughout history,

as has the acceptability their usage, phrases around suicide are both used to hurt

others beyond their naming or descriptive uses (as nouns, adjectives or verbs), but

also in a casual unthinking manner.

The examination within this paper has looked at how these different words

can be used to hurt and where they can support; where language becomes either a

shield or a sword. What must be remembered is that language is learned from

childhood; how we use words is dependent upon how we learned language to begin

with and with whom we learned it. Language is ever-changing, whether it is what

words mean or the way in which they are used and by whom; it cannot simply be

presumed that words can be used in the same way tomorrow as they were yesterday

and even today. Words can move from benign meanings to hurtful ones, or be

reclaimed from harmful use into empowered phrases. We must always seek to

continually learn language, to understand the hurt they can inflict, and to recognise

the impact upon social inclusion or exclusion. With such compassion, it can be

argued that language would become more a shield than sword. If language usage

reflects the speakers lived experience and can so deeply impact upon the listener,

then understanding how to better understand the dynamic nature of these constructs

is vital.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution made by the Collaborative Research

Network on Mental Health and Well-Being in Rural and Regional Communities,

supported by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and

Tertiary Education, Commonwealth Government of Australia.

157

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

References

Abbeduto, L. (2009). Editorial. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental

Disability 114(1), 1-2.

Ali, A., Scior, K., Ratti, V., Strydom, A., King, M., & Hassiotis, A. (2013).

Discrimination and Other Barriers to Accessing Health Care: Perspectives of

Patients with Mild and Moderate Intellectual Disability and Their Carers. PLOS

One. doi:0.1371/journal.pone.0070855

APA (American Psychiatric Association). (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders (1st edition). American Psychiatric Association, Washington.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders (4th edition: text revision).American Psychiatric Association,

Washington.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders (5th edition). American Psychiatric Association, Washington.

Beaton, S. J., Forster, P. M., & Maple, M. (2012). The language of suicide. The

Psychologist, 25(10), 731.

Bleich, E. (2011). The rise of hate speech and hate crime laws in liberal

democracies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(6), 917-934.

Block, P. (2000). Sexuality, fertility, and danger: Twentieth-century images of women

with cognitive disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 18(4), 239-255.

Butler, J. (1997). Excitable speech: A politics of the performative. Routledge, New

York.

Canetto, S. S. (1997). Meanings of gender and suicidal behavior during

adolescence. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 17, 339-351.

Canetto, S. S., & Lester, D. (1998). Gender, culture, and suicidal behavior.

Transcultural Psychiatry, 35, 163-190.

CNN. (2012). Ann Coulter's backward use of the 'r-word'. Retrieved from

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/10/23/living/ann-coulter-obama-tweet/index.html.

Connell, R. W. (1992). A very straight gay: Masculinity, homosexual experience, and

the dynamics of gender. American Sociological Review, 57(6), 735-751.

Culler, J. (1976). Saussure. London: Fontana.

Cvinar, J. G. (2005). Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: A review of the

literature. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 41, 14-21.

de Saussure, F. (1910-1911). Saussures third course of lectures on General

Linguistics (1910-1911): From the notebooks of Emile Constantin. Oxford:

Pregamon Press.

Delgado, R. & Stefancic, J. (2004). Understanding words that wound. Boulder, CO,

US: Westview Press.

Devitt, M. & Sterelny, K. (1999). Language and reality: An introduction to the

philosophy of language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dune, T. (2012). Constructions of sexuality and disability: Implications for people

with cerebral palsy. Saarbrcken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Forchtner, B. (2012). Critical discourse analysis. The Encyclopedia of Applied

Linguistics. doi: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0272

Garrett, P. B., & Baquedano-Lopez, P. (2002). Language socialization: Reproduction

and continuity, transformation and change. Annual Review of Anthropology,

31, 339-361.

Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (4th

ed.). New York: Routledge.

158

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Grew, T. (2007a). BBCs attitude to homophobic language damages children.

Retrieved

from

http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2007/07/05/bbcs-attitude-tohomophobic-language-damages-children/

Grew, T. (2007b). Government committed to stamping out gay bullying. Retrieved

from

http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2007/07/05/government-committed-tostamping-out-gay-bullying/

Hall, E. (2005). The entangled geographies of social exclusion/inclusion for people

with learning disabilities. Health & Place, 11(2), 107-115.

Harris, R. (1987). A critical commentary on the Cours de Linguistique Generale.

Duckworth, London.

Harris. R. (1990). Language, Saussure and Wittgenstein: How to play games with

words. London: Routledge.

Hollows, J. (2002). The bachelor dinner: Masculinity, class and cooking in Playboy,

1953-1961. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 16(2), 143-155.

Hurford, J. R. (1989). Biological evolution of the Saussurean sign as a component of

the language acquisition device. Lingua, 77, 187-222.

Keely, K., & Fink, L. (2011). Dangerous words: Recognizing the power of language

by researching derogatory terms. English Journal, 100(4), 55-60.

Leets, L. (2002). Experiencing hate speech: Perceptions and responses to antisemitism and antigay speech. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 341-361.

Lengell, S. (2012). Ann Coulter defends saying 'R-word'. Retrieved from

http://www.washingtontimes.com/blog/inside-politics/2012/oct/26/ann-coulterdefends-saying-r-word/

Lester, D. (1996). Sexism in suicidology. Homeostasis, 37, 83-88.

Lester, D. (2012). Reflections on jokes and cartoons about suicide. Death Studies,

36, 664-674.

Lewis, V., & Kellett, M. (2004). Disability. In: Fraser, S., Lewis, V., Ding, S., Kellett,

M. & Robinson, C. (Eds.). Doing research with children and young people (pp.

191-205). London: Sage Publications.

Macklemore.

(2012).

Same

love,

The

heist.

Retrieved

from

http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/macklemore/samelove.html

Maple, M., Edwards, H., Plummer, D., & Minichiello, V. (2010). Silenced voices:

Hearing the stories of parents bereaved through the suicide death of a young

adult child. Health & Social Care in the Community, 18(3), 241-248.

Minois, G. (1999). History of suicide: Voluntary death in Western culture. Baltimore:

The John Hopkins University Press.

Mostert, M. (2002). Useless eaters: Disability as genocidal marker in Nazi Germany.

The Journal of Special Education, 36, 157-170.

Nicholson, L., & Cooper, S. A. (2013). Social exclusion and people with intellectual

disabilities: a ruralurban comparison. Journal of Intellectual Disability

Research, 57(4), 333-346.

Online

Etymology

Dictionary.

(2013).

Gay.

Retrieved

from

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=gay&sear

chmode=none

Perry, K. (2008). Ur So Gay, One of the Boys. Retrieved from

http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/katyperry/ursogay.html

RC. (2010). Weekly US music releases: Katy Perry, Usher, Eels, and Fantasia. The

Independent. 23rd August. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/artsentertainment/music/weekly-us-music-releases-katy-perry-usher-eels-andfantasia-2059960.html

159

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

R-Word. (2012a). R-word counter. Retrieved from http://www.rwordcounter.org/

R-Word. (2012b). Spread the word to stop the word. Retrieved from http://www.rword.org/Default.aspx

Sanneh, K., (2007). Can the star make himself a star? The New York Times. 1st

April.

Retrieved

from

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/01/arts/music/01sann.html?pagewanted=all

&_r=0

Shea, P. B. (1999). Defining madness. Sydney: Hawkins Press.

Sherwin, A. (2006). Gay means rubbish, says BBC. London: Times newspaper

online. Retrieved from http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/arts/article2406394.ece

Siperstein, G., Pociask, S. & Collins, M. (2010). Sticks, stones, and stigma: A study

of students' use of the derogatory term retard. Intellectual and

Developmental Disabilities, 48(2), 126-134.

Sommer-Rotenberg, D. (1998). Suicide and language. Canadian Medical

Association Journal, 159(3), 239-240.

Sudak, H., Maxim, K. & Carpenter, M. (2008). Suicide and stigma: A review of the

literature and personal reflections. Academic Psychiatry, 32, 136-142.

Timbaland. (2007). Kill Yourself, Timbaland presents shock value. Retrieved from

http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/timbaland/killyourself.html

United Nations General Assembly. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with

disabilities.

Retrieved

from

http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml

Urban

Dictionary.

(2009).

Going

the

full

retard.

Retrieved

from

http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=going+full+retard

Urban

Dictionary.

(2013).

Gay.

Retrieved

from

http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Gay&defid=2220325

US Congress. (2012). S. 2781 (111th): Rosas law. Retrieved November from

http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/s2781

Van Gelder, L. (2007). Arts, briefly. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/12/arts/12arts.html?pagewanted=print

Wark, S., Hussain, R., & Edwards, H. (2014). Impediments to community-based care

for people ageing with intellectual disability in rural New South Wales. Health

& Social Care in the Community, 22(6), 623-633.

Warner, S. (2012). Acts of gaiety: LGBT performance and the politics of pleasure.

Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Winterman, D. (2008). How 'gay' became children's insult of choice. Retrieved from

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7289390.stm

World Health Organisation. (2012). Mental health definition: intellectual disability.

Retrieved

from

http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/healthtopics/noncommunicable-diseases/mentalhealth/news/news/2010/15/childrens-right-to-family-life/definition-intellectualdisability.

Zimbardo, P. (2008). The Lucifer effect. New York: Random House.

160

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Biographical notes

Kathy McKay (PhD) is a researcher and lecturer in the School of Health at the

University of New England, Australia. Her research focuses on narratives of

suicidality and self-harm from marginalised communities and within literary spaces.

Stuart Wark (PhD) is the second year academic coordinator with the School of

Rural Medicine at the University of New England, with primary research interests in

the fields of intellectual disability, ageing and gerontology, rurality, and mental health.

Virginia Mapedzahama has a PhD in Sociology from the University of South

Australia. She held a Post Doctoral Research Fellowship at Collaborative Research

Network for Mental Health in Rural and Regional Communities at the University of

New England. Her research interest is understanding the social construction of all

categories of difference, meanings attached to this difference, how it is signified,

lived and its implications for those assigned difference. She explores this interest in

the context of migration, diaspora, blackness, race, racism and ethnicity.

Tinashe Dune holds Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Psychology from Carleton

University, a Master of Public Health in Human Sexuality from the Institute for

Advanced Study in Human Sexuality and a PhD in Behavioural and Social Science

in Health from the University of Sydney. Dr Dune was a Post Doctoral Research

Fellow within Collaborative Research Network for Mental Health in Rural and

Regional Communities at the University of New England (UNE) and is currently a

Lecturer in Interprofessional Health Science at the University of Western Sydney.

Her teaching, research and community engagement focus is on marginalised

populations and social determinants of health.

Saifur Rahman holds a master and PhD degree in Epidemiology and Population

Health from Johns Hopkins USA and the Australian National University respectively.

He recently completed a Post Doctoral Research Fellowship at Collaborative

Research Network for Mental Health in Rural and Regional Communities, University

of New England (UNE) with a primary interest in design and implementation health

research that target Aboriginal and multicultural Australian minority groups.

161

Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(1), 2015

Catherine MacPhail holds a PhD from the University of the Witwatersrand, South

Africa. She is a Lecturer in the School of Health at the University of New England,

Australia and holds honorary positions at the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV

Institute and in the School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand. Her

primary research interest is adolescent sexual health and wellbeing.

162

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Duterte's Swear Words and their Pragmatic FunctionsDokumen28 halamanDuterte's Swear Words and their Pragmatic FunctionsAlberto Solis Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- O Critică A PCDokumen14 halamanO Critică A PCAna GrigoriuBelum ada peringkat

- FinalpaperDokumen21 halamanFinalpaperapi-406227042Belum ada peringkat

- Speech Sound and Social AccentDokumen4 halamanSpeech Sound and Social AccenthanifBelum ada peringkat

- ResearchpprDokumen16 halamanResearchpprapi-301278358Belum ada peringkat

- Bury, S. M., Jellett, R., Spoor, J. R., & Hedley, D. (2020) - It Defines Who I Am or It's Something I Have"Dokumen11 halamanBury, S. M., Jellett, R., Spoor, J. R., & Hedley, D. (2020) - It Defines Who I Am or It's Something I Have"Tomislav Cvrtnjak0% (1)

- The Politeness Strategies of Negation Used by English and BugineseDokumen12 halamanThe Politeness Strategies of Negation Used by English and BuginesebudiarmanBelum ada peringkat

- Taboo Words Term Paper (Dania)Dokumen19 halamanTaboo Words Term Paper (Dania)Aumnia JamalBelum ada peringkat

- Love 2Dokumen24 halamanLove 2JalBelum ada peringkat

- Article BlogDokumen11 halamanArticle BlogShabana qaisarBelum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal in English FullDokumen5 halamanResearch Proposal in English FullIan FelizardoBelum ada peringkat

- People and TaboosDokumen3 halamanPeople and TaboosVivian Alejandra AguirreBelum ada peringkat

- Berowa Duterte SwearingDokumen22 halamanBerowa Duterte Swearingmacy kang (maceeeeh)Belum ada peringkat

- Dimension About Words in The LanguageDokumen5 halamanDimension About Words in The LanguageDoctora ArjBelum ada peringkat

- Jay PDFDokumen33 halamanJay PDFYSJOS100% (1)

- Personality As Manifest in Word UseDokumen13 halamanPersonality As Manifest in Word UsejongohBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 2Dokumen4 halamanLesson 2rommel nicolBelum ada peringkat

- Duterte LinggDokumen29 halamanDuterte LingggeegeegeegeeBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Hollywood Films on University Students' Use of SlangDokumen11 halamanImpact of Hollywood Films on University Students' Use of SlangZeeo ZiaBelum ada peringkat

- Power of Swearing: What We Know and What We Don'tDokumen16 halamanPower of Swearing: What We Know and What We Don'tUmmil KhairahBelum ada peringkat

- The Negation Bias: When Negations Signal Stereotypic ExpectanciesDokumen15 halamanThe Negation Bias: When Negations Signal Stereotypic ExpectanciesMarcBraydonBelum ada peringkat

- Now You See Me, Now You Mishear Me: Raciolinguistic Accounts of Speech Perception in Different English VarietiesDokumen16 halamanNow You See Me, Now You Mishear Me: Raciolinguistic Accounts of Speech Perception in Different English VarietiesParintins ParintinsBelum ada peringkat

- Dewaele (2016) articleDokumen16 halamanDewaele (2016) articleozigan16Belum ada peringkat

- An Analysis of Swearing Words Used by Characters In: Blood Father MovieDokumen17 halamanAn Analysis of Swearing Words Used by Characters In: Blood Father MovieArvind SrivastavaBelum ada peringkat

- Presupposition Triggers in Oral and Online NewsDokumen14 halamanPresupposition Triggers in Oral and Online NewsnnnBelum ada peringkat

- Mad Studies and Neurodiversity - A DialogueDokumen6 halamanMad Studies and Neurodiversity - A DialogueJames BarnesBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Sociolinguistics SurveyDokumen12 halamanTugas Sociolinguistics SurveynurhadihamkaBelum ada peringkat

- Absalon, KR (Intro)Dokumen10 halamanAbsalon, KR (Intro)Kent Ruen AbsalonBelum ada peringkat

- Language and Culture (Yuni & Ika) Kelompok 10Dokumen8 halamanLanguage and Culture (Yuni & Ika) Kelompok 10Mukamat SukroniBelum ada peringkat

- Multicultural CompetenceDokumen5 halamanMulticultural CompetenceLiz PerezBelum ada peringkat

- EngrishDokumen8 halamanEngrishAditya FarhanBelum ada peringkat

- Running Head: Effects of Um and Uh On Intelligence 1Dokumen21 halamanRunning Head: Effects of Um and Uh On Intelligence 1Fatima-Elsalyn KahalBelum ada peringkat

- Revisiting The Representation of Developmental Disabilities in Children's Picture Books: A Narrative ReviewDokumen8 halamanRevisiting The Representation of Developmental Disabilities in Children's Picture Books: A Narrative Reviewvinay kumarBelum ada peringkat

- Linguistic Stereotyping and Its Effects on CommunicationDokumen23 halamanLinguistic Stereotyping and Its Effects on CommunicationGebreiyesus MektBelum ada peringkat

- Deafness, Disability and Inclusion: The Gap Between Rhetoric and PracticeDokumen18 halamanDeafness, Disability and Inclusion: The Gap Between Rhetoric and PracticelitsakipBelum ada peringkat

- New ProposalDokumen24 halamanNew Proposalryza mauryzBelum ada peringkat

- DEFINITION of Political CorrectnessDokumen2 halamanDEFINITION of Political CorrectnessRachelle Anne CernalBelum ada peringkat

- MMMS1713Dokumen8 halamanMMMS1713Ahsani Taq WimBelum ada peringkat

- Analyzing ReportDokumen3 halamanAnalyzing ReportMubarak RedwanBelum ada peringkat

- Political CorrectnessDokumen6 halamanPolitical CorrectnessОльга СавкоBelum ada peringkat

- Politeness - Strategies - Analysis - Reflected - Little WomenDokumen15 halamanPoliteness - Strategies - Analysis - Reflected - Little WomenAndreas HilmanBelum ada peringkat

- Persuasive Strategies in Presidential Spokesperson Atty. Harry Roque Jr.'s Speeches: A Discourse AnalysisDokumen17 halamanPersuasive Strategies in Presidential Spokesperson Atty. Harry Roque Jr.'s Speeches: A Discourse AnalysisPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Name: Andre Nayoan Class: D NIM: 321420076Dokumen6 halamanName: Andre Nayoan Class: D NIM: 321420076Andre NayoanBelum ada peringkat

- Joshua Habgood-Coote,: University of Bristol, Bristol, United KingdomDokumen49 halamanJoshua Habgood-Coote,: University of Bristol, Bristol, United KingdomRintintin OlacheaBelum ada peringkat

- Creating Whole Messages for Effective CommunicationDokumen3 halamanCreating Whole Messages for Effective CommunicationЯна ЯрохаBelum ada peringkat

- Universty of Ilorin, Ilorin, Kwara State: Level: 200 LevelDokumen12 halamanUniversty of Ilorin, Ilorin, Kwara State: Level: 200 Levelbalogun toheeb o.Belum ada peringkat

- Analysis of The President's Contexts in Speaking Tough LanguageDokumen5 halamanAnalysis of The President's Contexts in Speaking Tough LanguageJournal of Interdisciplinary Perspectives100% (1)

- Cultural Relativism's Impact on University PositionsDokumen12 halamanCultural Relativism's Impact on University PositionsVianne ZarateBelum ada peringkat

- "Drowning in Negativism, Self-Hate, Doubt, Madness": Linguistic Insights Into Sylvia Plath's Experience of Depre..Dokumen15 halaman"Drowning in Negativism, Self-Hate, Doubt, Madness": Linguistic Insights Into Sylvia Plath's Experience of Depre..Fazelah NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Political CorrectnessDokumen6 halamanPolitical CorrectnessLarisa PopaBelum ada peringkat

- Linguagem Inclusiva PDFDokumen36 halamanLinguagem Inclusiva PDFTatiana Aragão PereiraBelum ada peringkat

- Cross Cult Socio Lingual Biased 2Dokumen12 halamanCross Cult Socio Lingual Biased 2goal.moonlinaBelum ada peringkat

- Activity ProposalDokumen13 halamanActivity ProposalDonna Belle Gonzaga DacutananBelum ada peringkat

- Dimension About Words in The Language Lit506Dokumen17 halamanDimension About Words in The Language Lit506Doctora ArjBelum ada peringkat

- Discourse, Small D, Big D: James Paul GeeDokumen5 halamanDiscourse, Small D, Big D: James Paul GeemdmsBelum ada peringkat

- FINALChapt Mechanismsof Linguisticbias BeukeboomDokumen32 halamanFINALChapt Mechanismsof Linguisticbias BeukeboomredeatBelum ada peringkat

- Vogel, Rose, Roberts, & Eckles, 2014Dokumen18 halamanVogel, Rose, Roberts, & Eckles, 2014AlinaBelum ada peringkat

- Vogel, Rose, Roberts, & Eckles, 2014 PDFDokumen18 halamanVogel, Rose, Roberts, & Eckles, 2014 PDFAlinaBelum ada peringkat

- Practitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Social SkillsDari EverandPractitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Social SkillsBelum ada peringkat

- Supporting Deaf Culture Whilst Looking for a Cure: Conflicting Responses to DeafnessDari EverandSupporting Deaf Culture Whilst Looking for a Cure: Conflicting Responses to DeafnessBelum ada peringkat

- Read MeDokumen2 halamanRead MeEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- IntroductionDokumen1 halamanIntroductionEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Autocad 2D & 3DDokumen10 halamanAutocad 2D & 3DEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Latihan IllustratorDokumen7 halamanLatihan IllustratorEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Karakter KartunDokumen43 halamanKarakter KartunEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Dimension With Gradients Poster DesignDokumen21 halamanDimension With Gradients Poster DesignEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- When It Can'T Be Done, Do It. If You Don'T Do It, It Doesn'T ExistDokumen1 halamanWhen It Can'T Be Done, Do It. If You Don'T Do It, It Doesn'T ExistEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- How to Create a Kawaii Soda Shop Pattern in IllustratorDokumen32 halamanHow to Create a Kawaii Soda Shop Pattern in IllustratorEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- IGCS Bulletin Vol. 4 Issue 3 July 2015 FinalDokumen11 halamanIGCS Bulletin Vol. 4 Issue 3 July 2015 FinalEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Waste Water Review Paper 2015Dokumen9 halamanWaste Water Review Paper 2015Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Asseban J.haz - Mat.2015version PublieeDokumen8 halamanAsseban J.haz - Mat.2015version PublieeEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Management Plan For A Multi-Level Parking Project - A Case StudyDokumen7 halamanEnvironmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Management Plan For A Multi-Level Parking Project - A Case StudyEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Waste Management: R. Modolo, V.M. Ferreira, L.M. Machado, M. Rodrigues, I. CoelhoDokumen8 halamanWaste Management: R. Modolo, V.M. Ferreira, L.M. Machado, M. Rodrigues, I. CoelhoEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Modeling of Biological Wastewater Treatment Facilities: A ReviewDokumen3 halamanModeling of Biological Wastewater Treatment Facilities: A ReviewEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Luz Et Al. 2015Dokumen17 halamanLuz Et Al. 2015Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Passive Treatment of Metal and Sulphate-Rich Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) Using Mixed Limestone, Spent Mushroom Compost and Activated SludgeDokumen6 halamanPassive Treatment of Metal and Sulphate-Rich Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) Using Mixed Limestone, Spent Mushroom Compost and Activated SludgeEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Debating Humanity. Towards A Philosophical Sociology: Daniel CherniloDokumen20 halamanDebating Humanity. Towards A Philosophical Sociology: Daniel CherniloEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Confidentiality in Mobile Voting SystemDokumen34 halamanConfidentiality in Mobile Voting SystemEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- IAAA Article 88Dokumen15 halamanIAAA Article 88Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- 11 - Kennan Cable-Minakov 2Dokumen4 halaman11 - Kennan Cable-Minakov 2Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Société Québécoise de Science Politique: Preserve and Extend Access ToDokumen29 halamanSociété Québécoise de Science Politique: Preserve and Extend Access ToEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Story GameDokumen20 halamanStory GameEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Review Energy Efficient Sensor Selection For Data Quality and Load Balancing 1Dokumen3 halamanReview Energy Efficient Sensor Selection For Data Quality and Load Balancing 1Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Mikkelsen Cohen 2015Dokumen30 halamanMikkelsen Cohen 2015Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- JC MT Jalpp 2014Dokumen10 halamanJC MT Jalpp 2014Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- EQPAMVol4No3July2015 Schatten Seva OkresaDuric CCUDokumen52 halamanEQPAMVol4No3July2015 Schatten Seva OkresaDuric CCUEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- JC MT Jalpp 2014Dokumen10 halamanJC MT Jalpp 2014Eka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- Syllabus - Poverty Race and The Politics of ReproductionDokumen3 halamanSyllabus - Poverty Race and The Politics of ReproductionEka Wahyudi NggoheleBelum ada peringkat

- QuestionnaireDokumen7 halamanQuestionnaireFaiqa SabirBelum ada peringkat

- Psi 2010 44 CateringDokumen5 halamanPsi 2010 44 CateringChef ShaneBelum ada peringkat

- Alternative Work Arrangement November 16-20, 2020Dokumen4 halamanAlternative Work Arrangement November 16-20, 2020Maria Kristel L PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Cerebrospinal FluidDokumen12 halamanCerebrospinal FluidPavithran PBelum ada peringkat

- GSM Q PaperDokumen3 halamanGSM Q PapersivaBelum ada peringkat

- Intro To ISO 27001Dokumen8 halamanIntro To ISO 27001kashifbutty2kBelum ada peringkat

- Van Koetsveld and His 'School For Idiots' in The Hague (1855-1920) - GenderDokumen20 halamanVan Koetsveld and His 'School For Idiots' in The Hague (1855-1920) - GenderPanayiota CharalambousBelum ada peringkat

- Microbiological and Nutritional Qualities of Burukutu Sold in Mammy Market Abakpa, Enugu State, NigeriaDokumen6 halamanMicrobiological and Nutritional Qualities of Burukutu Sold in Mammy Market Abakpa, Enugu State, NigeriasardinetaBelum ada peringkat

- Etoricoxib For Arthritis and Pain ManagementDokumen14 halamanEtoricoxib For Arthritis and Pain ManagementruleshellzBelum ada peringkat

- ABO IncompatibilityDokumen16 halamanABO IncompatibilityMay Lacdao100% (1)

- BARTHELDokumen2 halamanBARTHELRene John FranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- Immunization HandbookDokumen200 halamanImmunization Handbooktakumikuroda100% (1)

- Hyogo Framework of ActionDokumen90 halamanHyogo Framework of ActionDipendraGautamBelum ada peringkat

- AEM3540 Management Score Sheet and Examiner BreifDokumen5 halamanAEM3540 Management Score Sheet and Examiner BreifAbdullah Al MasumBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines and Toolkit For Massive Transfusion in Nova ScotiaDokumen64 halamanGuidelines and Toolkit For Massive Transfusion in Nova Scotiagasparsoriano3371Belum ada peringkat

- Trauma Copiilor AbandonatiDokumen132 halamanTrauma Copiilor AbandonatiPaula CelsieBelum ada peringkat

- Legal and Policy Mechanisms for Urban Pollution ControlDokumen511 halamanLegal and Policy Mechanisms for Urban Pollution ControlPASTOR STARBelum ada peringkat

- SerologyDokumen33 halamanSerologyGEBEYAW ADDISUBelum ada peringkat

- Abraham PDFDokumen8 halamanAbraham PDFAnonymous bklKGdM1pBelum ada peringkat

- Xi-Biden Summit: US Statement in FullDokumen3 halamanXi-Biden Summit: US Statement in FullscmpBelum ada peringkat

- Glad Well RitalinDokumen6 halamanGlad Well Ritalinonessa7Belum ada peringkat

- Aesthetic Management of Immediate Anterior Tooth Replacement With Ovate Pontic: A Case Report PDFDokumen5 halamanAesthetic Management of Immediate Anterior Tooth Replacement With Ovate Pontic: A Case Report PDFAnita PrastiwiBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan ON PyelonephritisDokumen11 halamanLesson Plan ON PyelonephritisVeenasravanthiBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Management Planning: Namgay Lham M.SC 2 Year KconDokumen30 halamanNursing Management Planning: Namgay Lham M.SC 2 Year KconNamgay Lham100% (1)

- Halamid MSDS ENGDokumen11 halamanHalamid MSDS ENGKelvin Mendoza ChavarríaBelum ada peringkat

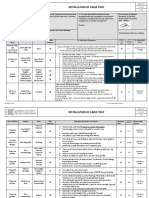

- WMS 155+Installation+of+Cable+Tray+Dokumen6 halamanWMS 155+Installation+of+Cable+Tray+monik_atabaresBelum ada peringkat

- EPB 261 - Chemical Use and Storage at WaterworksDokumen3 halamanEPB 261 - Chemical Use and Storage at WaterworksKONSTANTINOS TOMAZISBelum ada peringkat

- Coursera Drug Developement PDFDokumen1 halamanCoursera Drug Developement PDFVasilis TsinterisBelum ada peringkat

- How Do You Suppose Milken Maintains His Self-Esteem When So Many People Despise Him As A Very Wealthy White Color Criminal?Dokumen3 halamanHow Do You Suppose Milken Maintains His Self-Esteem When So Many People Despise Him As A Very Wealthy White Color Criminal?Karma GurungBelum ada peringkat

- Parson Executive Order 21-10Dokumen1 halamanParson Executive Order 21-10KevinSeanHeldBelum ada peringkat