Hematologi

Diunggah oleh

Mulyono Aba AthiyaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Hematologi

Diunggah oleh

Mulyono Aba AthiyaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International Journal of Biomedical Research

ISSN: 0976-9633 (Online)

Journal DOI:10.7439/ijbr

CODEN:IJBRFA

Case Report

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: an interesting presentation and

review of literature

Sudarshan K. Shetty*, Siddarth S. Joshi, Vijaya M. Shenoy and Sumanth Bellipady Shetty

Department of Pediatrics, K. S. Hegde Medical Academy, NITTE University, India

*Correspondence Info:

Dr Sudarshan K. Shetty*

Associate Professor

Department of Pediatrics,

K. S. Hegde Medical Academy, NITTE University, India

Email: sudarshanshetty1975@gmail.com

Abstract

Hemolytic anemia is caused either due to intrinsic red cell defects as in membranopathy/enzymopathy or

acquired by extrinsic factors as auto antibodies. We are reporting a 3 year old child case referred to our center as a renal

disease, with edema, high BP readings and red colored urine, which on our evaluation turned out to be autoimmune

hemolytic anemia. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, though rare in children, needs to be diagnosed early and followed

closely as it may begin with deceptive initial presentation.

Keywords: autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), acquired hemolytic anemia

1. Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) represents a group of acquired hemolytic anemias resulting from the

development of auto antibodies against surface antigens of red blood cells 1. Based on temperatures at which auto antibodies

react with red blood cells, AIHA is classied into warm and cold antibody types. Warm antibody AIHA occurs

predominantly in children aged 212 years. The antibodies belong to IgG class, react at or above 37 .C, do not require

complement for activity and do not produce agglutination in vitro. On the other hand cold antibody AIHA occurs less

commonly in children. Antibodies are of IgM classes which react at temperatures 37 . C, require complement for activity and

produce spontaneous agglutination of red blood cells in vitro2. Mixed type AIHA is the presence of both warm and cold auto

antibodies3. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia is an uncommon cause of hemolytic anemia in children with an incidence of

approximately 0.2 per 100,000 in 1120 years age group 1,2. We are reporting an interesting presentation of AIHA in a 3

year old child.

2. Case Report

A 3 year old boy was referred to us with history suggestive of renal edema, red colored urine, high

BPmeasurementsand progressive anemia.Our working diagnosis was glomerulonephritis, although the age at presentation

was not typical for acute glomerulonephritis (AGN). His repeated BP measurements at different times of the day were

between 50th and 90th centiles for his age and height and needed no treatment. His urine was red colored on gross

appearance, no red blood cells (RBC) on microscopy, trace proteinuria and was positive for hemoglobin.Hishemoglobin was

6 gm/dL, total bilirubin was 1.8mg/dL, indirect bilirubin was 1.4mg/dL and direct bilirubin was 0.4mg/dL. His peripheral

smear showed microspherocytes and fragmented RBCs with a corrected reticulocyte count of 20%. His serum creatinine

was 0.4 mg/dL,mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin

concentration (MCHC) and serum electrolytes like sodium, potassium and chlorides were within normal limits. Ultra

sonographic examination of abdomen showed normal sized kidneys and no mass lesions or free fluids indicating a normal

renal function. HisPoly specific Direct Antiglobulin test (DAT) (Coombs test) was positive,but mono specific DAT could

IJBR (2013) 04 (07)

www.ssjournals.com

Shetty et al

356

not be done due to lack of facility at our center. The osmotic fragility test and G6PD enzyme levels were within normal

limits. With these investigations, an intravascular hemolysis state was considered. Acute infections causing severe anemia

like malariawere ruled out in this child. We also considered secondary causes of hemolysis like Mycoplasma infection as a

possible cause of hemolysis and treated him with azithromycin for 5 days with no improvement of anemia. Hence we

considered primary AIHA as a possible diagnosis and the child was treated with oral prednisolone ata dose of 2mg/kg/day

daily. After 4 weeks of steroids his hemoglobin has increased to 12.8gm/dl and urine is clear. His repeat peripheral smear

examination showed no evidence ofhemolysis. Although there is no recommendation of the duration of prednisalone

treatment or any recommendations regarding tapering the dose, we reduced the prednisalone dose to 1mg/kg/day at the end

of 4 weeks, which was continued till 12 weeks and stopped. At the last follow up his hemoglobin was 12.4gm/dl and doing

well in school.

3. Discussion

In children, hemolytic anemia is usually caused by intrinsic defects in red blood cells like in membrane defects, red

cell enzyme deciencies or hemoglobin abnormalities and most of them are inherited in nature. Acquired Hemolytic

anemiasusually seen due to extrinsic factors 1. AIHA belongs to a group of acquired hemolytic anemias which results from

the development of auto antibodies directed against antigens on the surface of patients own red blood cells. Majority of the

cases are mediated by warm reactive auto antibodies while AIHA due to cold reactive antibodies are less common 2.

Diagnosis of AIHA is based on evidence of hemolyticanemia consisting of anemia, jaundice, splenomegaly, reticulocytosis,

raised serum bilirubin and a positive DAT ( direct agglutination test ) 1. Once AIHA has been identied, differentiation

between warm and cold antibodies can be done by monospecic DAT which also identies responsible mechanisms. If the

reaction is positive with anti IgG and negative with anti C3d, it is usually due to warm antibodies which are common in

idiopathic or drug associated AIHA. If the reaction is positive with both anti IgG and anti C3d, it also indicates warm auto

antibodies and is more common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and idiopathic AIHA. In cold

agglutinin disease (CAD), the reaction is positive with anti C3d but negative with anti IgG 10.There is also presence of

agglutination of red cells at temperatures 37 .C in cold type of AIHA 2.Autoimmune hemolytic anemia is known to be

associated with infection, malignancy or other autoimmune diseases but in most cases it is idiopathic 1, 2. Cause of AIHA in

children remained obscure in majority of cases labeling them as idiopathic or primary 8, 11. Many medical conditions are

associated with AIHAsuch as viral infections, SLE, Mycoplasma pneumonia, immunization, tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus,

Hodgkins lymphoma, auto immune hepatitis, sepsis with bacterial endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus, GuillainBarre syndrome and Langerhan cell histiocytosis have been reported 3, 69, 11, 12. Hence long term regular follow ups are

needed. In AIHA, only single cell line is affected 1, 2 but there are rare reports with a combination of AIHA and immune

thrombocytopenia called Evans syndrome6, 11, 12.

Corticosteroid therapy is the mainstay of treatment in warm AIHA. But the duration and the dose of treatment is

not clear in literature. The treating physician has to tailor the dose based on clinical response. Transfusion of red cells in

AIHA can result in rapid in vivo destruction of transfused cells due to the presence of auto antibodies 12, 15. Transfusions are

of transient benet, but may be required initially in managing severe anemia. Immunosuppressive agents including

monoclonal anti-CD20 (Rituximab) may prove useful in refractory cases of warm AIHA. Splenectomy may help in some

cases of refractory AIHA 2,16.

4. Conclusion

AIHA has a wide spectrum of presentations varying from subtle to the obvious. As AIHA can be the initial

presentation of a more serious condition like Hodgkins lymphoma, the clinician needs to be cautious and closely follow the

patient regularly.

References

1.

De Gruchy GC. Thehaemolyticanaemias. In: Firkin FC,Chesterman CN, Penington DG, Rush BM, editors. De

Gruchys clinical haematology in medical practice, 5th edn. Edinburgh:Blackwell Science Ltd;1989.p172215.

2.

Segel GB. Hemolytic anemias resulting from extracellular factors. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB,

editors.Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 18thedn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p 204244.

IJBR (2013) 04 (07)

www.ssjournals.com

357

Shetty et al

3.

Culic S, Kuljis D, Ivankovic Z, Martinic R, Maglic P, Pavlov N et al. Various triggers for autoimmune haemolytic

anemia in childhood. Paediatr Croat 1999; 43: 20710.

4.

Sokol RJ, Hewitt S, Stamps BK. Autoimmune haemolysis: an 18- year study of 865 cases referred to regional

transfusion centre. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282: 202327.

5.

Mayer B, Yurek S, Kiesewetter H, Salama A. Mixed- type autoimmune haemolytic anemia: differential diagnosis and a

critical review of reported cases. Transfusion 2008; 48(10): 22292234.

6.

Jubinsky PT, Rashid N. Successful treatment of a patient with mixed warm and cold antibody mediated Evans

syndrome and glucose intolerance. Paediatr Blood Cancer 2005; 45: 347350.

7.

Sheth SS, Karande SC, NadkarniUB, Lahiri K, Jain MK, Shah MD.Autoimmunehaemolytic anemia: mixed type.

Indian Pediatr 1991; 28(3): 303304.

8.

Oliveira MC, Oliveira BM, Murao M, Vieira ZM, Gresta LT, Viana MB. Clinical course of autoimmune haemolytic

anemia: an observational study. J Pediatr 2006; 82 (1):5862.

9.

Wonderjem MJ, Overbeeke M, Som N, Chamuleau M, Jonkhoff AR, Zweegman S. Mixed autoimmune hemolysis in a

SLE patient due to aspecic and anti- Jka autoantibodies; case reportand review of the literature. Haematologica 2006;

91(1):3941.

10. Lichtin AE. Autoimmunehaemolytic anemia.www.merckmanuals.com/professional/sec11/ch131/ch131b.html. Accessed

15 Dec 2009.

11. Gupta V, Shukla J, Bhatia BD. Autoimmunehaemolytic anemia. Indian J Pediatr 2008; 75:45154

12. Park D, Yang C, Kim K. Autoimmunehaemolytic anemia in children. Yonsei Med J1987; 28(4):31321.

13. Videback A. Auto-immune haemolyticanaemia in systemic lupus erythematosis. Acta Med Scand1962; 171:18794.

14. Ling R, James B. Classic signs revisited. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (roth spots). Postgrad Med J1998;

74:581582.

15. SutaoneB, Jain N, Mathur NB, Khalil A. Blood transfusion in autoimmune haemolytic anemia: a practical problem.

Indian Pediatr1993; 30:264266.

16. Laverger G, Bancillon A, Schaison G. Treatment of autoimmune haemolytic anemia in children. Ann Pediatr1989;

36(8):519523.

17. Win N, Tiwari D,Keevil VL, Needs M, Lakhani A. Mixed-type autoimmune haemolyticanaemia: unusual cases anda

case associated with splenic T-cell angioimmunoblasticnon-Hodgkins lymphoma. Hematology 2007; 12(2): 159162

IJBR (2013) 04 (07)

www.ssjournals.com

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- SK Tim Satgas PDFDokumen5 halamanSK Tim Satgas PDFMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Diklat Rekam MedikDokumen196 halamanDiklat Rekam MedikMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction Diagnosi Faf109ebDokumen11 halamanSubclinical Thyroid Dysfunction Diagnosi Faf109ebainia taufiqaBelum ada peringkat

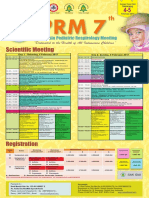

- IPRM 3rd AnnouncementDokumen1 halamanIPRM 3rd AnnouncementMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Name of The Participant: Mulyono Mulyono Country: IndonesiaDokumen1 halamanName of The Participant: Mulyono Mulyono Country: IndonesiaMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Transfusion Practice Guidelines For Medical Interns BangladeshDokumen42 halamanClinical Transfusion Practice Guidelines For Medical Interns Bangladeshratriprimadiati100% (1)

- Fadhilah Nur Fahada-2 PDFDokumen5 halamanFadhilah Nur Fahada-2 PDFMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Berani BerpendapatDokumen6 halamanBerani BerpendapatMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- P 0,05, Statistically Significant Independent T-Test Mann Whitney Pearson Chi SquareDokumen2 halamanP 0,05, Statistically Significant Independent T-Test Mann Whitney Pearson Chi SquareMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- P 0,05, Statistically Significant Independent T-Test Mann Whitney Pearson Chi SquareDokumen2 halamanP 0,05, Statistically Significant Independent T-Test Mann Whitney Pearson Chi SquareMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- 07 - Edisi Suplemen-2 18 - Diagnosis Dan Tatalaksana Hepatitis ADokumen2 halaman07 - Edisi Suplemen-2 18 - Diagnosis Dan Tatalaksana Hepatitis AMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Systematic Review PDSADokumen11 halamanSystematic Review PDSAMulyono Aba Athiya100% (1)

- Gambar LeptinDokumen1 halamanGambar LeptinMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Decreasing The Expression Level of Macrophage Cell PDFDokumen15 halamanDecreasing The Expression Level of Macrophage Cell PDFMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Skala SnapDokumen3 halamanSkala SnapMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Endocrine Test Protocols: Medical Investigation Facility Endocrinology & Diabetes UnitDokumen24 halamanEndocrine Test Protocols: Medical Investigation Facility Endocrinology & Diabetes UnitMulyono Aba Athiya100% (2)

- Arch Dis Child-2001-Chessells-321-5 PDFDokumen6 halamanArch Dis Child-2001-Chessells-321-5 PDFMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Hematologi ManifestationDokumen7 halamanHematologi ManifestationMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Predicting Preterm Labour DeliveryDokumen8 halamanPredicting Preterm Labour DeliveryMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Pasien Stem Cell (Dr. Galuh)Dokumen3 halamanPasien Stem Cell (Dr. Galuh)Mulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Prolonged Episodes of Acute Diarrhea Reduce Growth and Increase RiskDokumen9 halamanProlonged Episodes of Acute Diarrhea Reduce Growth and Increase RiskMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Sensitivity of BCG Inoculation and Tuberculin Skin TestDokumen3 halamanSensitivity of BCG Inoculation and Tuberculin Skin TestMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- BMC Antimicrobial Drugs For Persistent Diarrhoea of UnknownDokumen8 halamanBMC Antimicrobial Drugs For Persistent Diarrhoea of UnknownMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Clonidine Stimulation For GH Secretion in ChildrenDokumen2 halamanClonidine Stimulation For GH Secretion in ChildrenMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- The Burden of Diarrheal Diseases Among ChildrenDokumen7 halamanThe Burden of Diarrheal Diseases Among ChildrenMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Congenital Heart Disease: Causes, Clinical Effects and TreatmentDokumen9 halamanCongenital Heart Disease: Causes, Clinical Effects and TreatmentMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- NIPS Neonatal Pain Scale for Infants Birth to 1 YearDokumen1 halamanNIPS Neonatal Pain Scale for Infants Birth to 1 YearMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- CHF AAPDokumen11 halamanCHF AAPFajar Al-HabibiBelum ada peringkat

- The Effect of High Concentration OxygenDokumen3 halamanThe Effect of High Concentration OxygenMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Gagal Jantung Kanan, ManajemenDokumen21 halamanGagal Jantung Kanan, ManajemenMulyono Aba AthiyaBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Konsep Pembangunan Kesehatan Di Indonesia-1Dokumen8 halamanKonsep Pembangunan Kesehatan Di Indonesia-1PIPITBelum ada peringkat

- Angie ResumeDokumen2 halamanAngie Resumeapi-270344093Belum ada peringkat

- Peo 20051026 IssueDokumen92 halamanPeo 20051026 IssueAlan EscobedoBelum ada peringkat

- Riza T. Calixtro: ObjectivesDokumen2 halamanRiza T. Calixtro: ObjectivesLorinel MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- First Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in HospitalizedDokumen35 halamanFirst Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in HospitalizedFranco PacelloBelum ada peringkat

- FerritinDokumen24 halamanFerritinyundendoctorBelum ada peringkat

- Minutes of Meeting November 2020Dokumen2 halamanMinutes of Meeting November 2020Jonella Anne CastroBelum ada peringkat

- DR Sumit Garg Projec-IECDokumen10 halamanDR Sumit Garg Projec-IECkamlesh yadavBelum ada peringkat

- Hospitalized for Bleeding Peptic UlcerDokumen53 halamanHospitalized for Bleeding Peptic UlcerHoney Lyn AlebioBelum ada peringkat

- Panic DisorderDokumen14 halamanPanic DisorderMatthew MckenzieBelum ada peringkat

- Penguins Medicine August-SeptumberDokumen215 halamanPenguins Medicine August-SeptumberKhattabBelum ada peringkat

- Tricorder X PrizeDokumen4 halamanTricorder X PrizemariaBelum ada peringkat

- Certification of Health Care Provider For Family MBRDokumen4 halamanCertification of Health Care Provider For Family MBRapi-241312847Belum ada peringkat

- Scripta Medica 46 2 English PDFDokumen62 halamanScripta Medica 46 2 English PDFSinisa RisticBelum ada peringkat

- Advocacy PaperDokumen3 halamanAdvocacy Paperapi-478583234Belum ada peringkat

- Differential Diagnosis of Liver NoduleDokumen46 halamanDifferential Diagnosis of Liver NoduleJoydip SenBelum ada peringkat

- A Study To Assess The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Health Workers Regarding Nosocomial Infection at Selected Hospitals of Birtamode Municipality, JhapaDokumen5 halamanA Study To Assess The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Health Workers Regarding Nosocomial Infection at Selected Hospitals of Birtamode Municipality, JhapaIJCRM Research JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Biostatistics For CK Step 2 6.16.2019Dokumen37 halamanBiostatistics For CK Step 2 6.16.2019karan kauraBelum ada peringkat

- Public Health - Resume of Shah BookDokumen54 halamanPublic Health - Resume of Shah BookKami Dhillon83% (6)

- Top 100 Study Items For The Otolaryngology (ENT) Board ExaminationDokumen8 halamanTop 100 Study Items For The Otolaryngology (ENT) Board ExaminationsduxBelum ada peringkat

- Missouri Counties Sue Drug Companies Over Opioid CrisisDokumen274 halamanMissouri Counties Sue Drug Companies Over Opioid CrisisSam ClancyBelum ada peringkat

- The Expanded Program On ImmunizationDokumen26 halamanThe Expanded Program On ImmunizationJudee Marie MalubayBelum ada peringkat

- Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Dokumen2 halamanHepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Cristian urrutia castilloBelum ada peringkat

- JADWAL PELATIHAN IhcaDokumen1 halamanJADWAL PELATIHAN Ihcalilik ari prasetyoBelum ada peringkat

- Short-Term Clinical Outcomes and Safety Associated With Percutaneous Radiofrequency Treatment For Excessive SweatingDokumen10 halamanShort-Term Clinical Outcomes and Safety Associated With Percutaneous Radiofrequency Treatment For Excessive SweatingsadraBelum ada peringkat

- Cystic FibrosisDokumen4 halamanCystic Fibrosisapi-548375486Belum ada peringkat

- T3 Short Implant Surgical Manual: Preservation by DesignDokumen20 halamanT3 Short Implant Surgical Manual: Preservation by DesignMarco BarrosoBelum ada peringkat

- Toxoplasma Gondii.Dokumen21 halamanToxoplasma Gondii.Sean MaguireBelum ada peringkat

- Health Is The Most Expensive Thing in Our LifeDokumen7 halamanHealth Is The Most Expensive Thing in Our LifeKadek Santiari DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Branches of Medicine & Wards and Departements - EditkuDokumen31 halamanBranches of Medicine & Wards and Departements - EditkuGigih Sanjaya PutraBelum ada peringkat