Rainbow Rights Jurisprudence

Diunggah oleh

cmdelrioJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Rainbow Rights Jurisprudence

Diunggah oleh

cmdelrioHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

THE RAINBOW-COLORED ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM:

A COMMENTARY ON

LGBT JURISPRUDENCE*

NOTE

Diane Jane D. Dolot**

Jose Carlos P. Marin***

On April 8, 2014, the Supreme Court, in Imbong v. Ochoa,1 upheld the

constitutionality of Republic Act No. 10354, otherwise known as the

Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012 (RH Law).

While this decisions implications for the future landscape of Philippine

jurisprudence are almost endless in quantity and unprecedented in scale, its

impact on the general publicthat is, people whose lives are blissfully

unfettered by the formal study of lawhas to be considered. Indeed, the impact

of Imbong is not fully appreciated if its consequences on a national scale are not

considered. While the Court has penned multiple landmark cases in recent

memory, Disini v. Secretary of Justice2 and Araullo v. Aquino3 for example, few have

received the same widespread attention or were as closely watched as Imbong.

For individuals who do not make it their business to examine the inner

workings and nuances of the law, it is probable that their primary takeway from

Imbong is that it is an occasion when the State pursued a stance notwithstanding

the Catholic Churchs staunch opposition to the same. This shift in the States

attitude will likely have surprised most, considering the remarkable influence of

the Catholic Church in the crystallization of national policies throughout history.

For instance, the Philippines and Vatican City are the only states in the world

* Cite as Diane Jane Dolot & Jose Carlos Marin, Note, The Rainbow-Colored Elephant in the

Room: A Commentary on LGBT Jurisprudence, 88 PHIL. L.J. 937, (page cited) (2014).

** J.D., University of the Philippines (2016, expected); B.S. Accountancy, cum laude,

University of Santo Tomas (2009).

*** J.D., University of the Philippines (2016, expected); B.A. English Studies (AngloAmerican Literature), cum laude, University of the Philippines Diliman (2012).

1 G.R. No. 204819, Apr. 8, 2014.

2 G.R. No. 203335, Feb. 11, 2014; on the constitutionality of the Cybercrime Prevention

Act.

3 G.R. No. 209287, July 1, 2014; on the constitutionality of the Disbursement

Acceleration Program.

937

938

PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL

[VOL. 88 : 937

that do not have a divorce law.4 It can hardly be argued that such a glaring

distinction from the rest of the world has nothing to do with the fact that

divorce is not recognized by the Catholic Church. That being the case, it

becomes easy to appreciate just why exactly the Imbong ruling has limitless

ramifications even in the eyes of the general public. When will the State, through

the Court, next render a decision that runs counter to long-held beliefs of the

Catholic Church?

It is within this context that we deemed it appropriate to examine

significant pieces of jurisprudence that relate to a group of people whose

interests too often contradict the stance of the Catholic Churchthe Lesbian,

Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community. This review will focus on

three cases, namely: Silverio v. Republic of the Philippines,5 Republic of the Philippines v.

Cagandahan,6 and Ang Ladlad LGBT Party v. Commission on Elections.7 It is believed

that these cases will paint a complete picture of the state of Philippine LGBT

jurisprudence because two of them, Silverio and Cagandahan, involved LGBT

issues on an individual level, while one, Ang Ladlad, dealt with LGBT issues on

an institutional level.

On October 22, 2007, the Court, speaking through Justice Corona,

denied the petition of Rommel Silverio for a change of the name and sex that

were indicated in his birth certificate. The petitioner, a transsexual, alleged that

although he was male anatomically speaking, he feels, thinks and acts as a

female.8 Consistent with this allegation, Silverio underwent extensive hormone

therapy and had sexual reassignment surgery performed on his body. On the

basis of the fact that his physical body finally matched his internal state of mind,

the petitioner argued that changing his name to Mely9 and his sex to

female10 would actually be beneficial not only to himself but to the general

public because it would avoid confusionone of the grounds for a valid change

of name under Republic Act No. 9048. The trial court granted the petition not

on the basis of any particular piece of substantive law but on the basis of equity:

Firstly, the [c]ourt is of the opinion that granting the petition would be

more in consonance with the principles of justice and equity. With his

4 Carlos Conde, Philippines Stands All but Alone in Banning Divorce, THE NEW YORK

TIMES, June 17, 2011, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/18/world/asia/18iht-phil

ippines18.html?_r=0.

5 G.R. No. 174689, 537 SCRA 373, Oct. 22, 2007 [hereinafter Silverio].

6 G.R. No. 166676, 565 SCRA 72, Sep. 12, 2008 [hereinafter Cagandahan].

7 G.R. No. 190582, 618 SCRA 32, Apr. 8, 2010 [hereinafter Ang Ladlad].

8 Silverio, 537 SCRA at 380.

9 Id. at 381.

10 Id.

2014]

A COMMENTARY ON LGBT JURISPRUDENCE

939

sexual [re-assignment], petitioner, who has always felt, thought and

acted like a woman, now possesses the physique of a female.

Petitioners misfortune to be trapped in a mans body is not his own

doing and should not be in any way taken against him.

Likewise, the [c]ourt believes that no harm, injury [or] prejudice

will be caused to anybody or the community in granting the petition.

On the contrary, granting the petition would bring the much-awaited

happiness on the part of the petitioner and her [fianc] and the

realization of their dreams.11

The Supreme Court, however, reversed the trial courts decision. It held

that contrary to Silverios claim, changing his name and gender will cause more

confusion and may only create grave complications in the civil registry and the

public interest.12 The tenor of the Courts ruling in this case is that there is no

existing piece of legislation that can grant the relief prayed for by Silverio.

Notably, both the trial court and the Supreme Court had this point in

agreement. The difference, however, lies with the conclusion of the Court that it

cannot sustain the petition based on equity alone. While our jurisprudence is

replete with cases where the Court has granted petitions based on considerations

of equity and compassionate justice,13 the Court in Silverio declined to pursue a

similar line of reasoning and decided to take the more conservative view.

Interestingly, the first words of the case were not penned by Justice

Corona but were passages from the book of Genesis from the Christian Bible.14

Optimistically, the use of such text could have been justified by the literary

flavor it gave the decision; pessimistically, it demonstrates a clear bias by the

States highest judicial body in favor of an institution from which it is supposed

to be independent.

Almost a year later, on September 12, 2008, the Court promulgated

another ruling that touched on the issue of LGBT rights in the form of Republic

v. Cagandahan.15 The Court, speaking through Justice Quisumbing, granted the

petition of Jennifer Cagandahan to change the entries in her birth certificate that

formerly read as Jennifer Cagandahan and indicated her sex as female to

Id. at 382.

Id. at 387.

13See Soco v. Mercantile Corp. of Davao, G.R. No. 53364, 148 SCRA 526, Mar. 16,

1987; Engineering Equipment, Inc. v. Natl Lab. Rel. Commn, G.R. No. 59221, 133 SCRA 752,

Dec. 26, 1984; and New Frontier Mines, Inc. v. Natl Lab. Rel. Commn, G.R. No. L-51578, 129

SCRA 502, May 29, 1984.

14 When God created man, He made him in the likeness of God; He created them

male and female. Genesis 5:1-2, cited in Silverio, 537 SCRA 373

15 G.R. No. 166676, 565 SCRA 72, Sept. 12, 2008.

11

12

940

PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL

[VOL. 88 : 937

Jeff Cagandahan and male, respectively.16 Cagandahan had a medical

condition called Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH), which means that she

possesses both male and female characteristics.17 At first blush, this decision

seems to suggest that the Court has abandoned its stance in Silverio, but a closer

examination will reveal that the Court merely carved out a very narrow and

specific exception to the doctrine that it enunciated in Silverio. In fact,

notwithstanding the difference in the ruling of the Court in Cagandahan as

compared to Silverio, the Courts line of reasoning remained resoundingly similar.

As in the Silverio decision, the Court pointed out the absence of a law

that would explicitly allow it to grant the petition. Having admitted that it had no

secure basis in law that could justify a favorable ruling, the Court limited the area

of its consideration and the rationale of its decision strictly to the presence or

absence of CAH and the various pieces of medical testimony that were

presented by the petitioner. In effect, the decision of the Court to grant the

petition in this case turned upon the fact that Jennifer Cagandahan was

diagnosed with CAH. The Court, in this case, took pains to distance its ruling

from the exercise of its own judgment through this statement:

Respondent here has simply let nature take its course and has not

taken unnatural steps to arrest or interfere with what he was born

with. And accordingly, he has already ordered his life to that of a

male. Respondent could have undergone treatment and taken steps,

like taking lifelong medication, to force his body into the categorical

mold of a female but he did not. He chose not to do so. Nature has

instead taken its due course in respondents development to reveal

more fully his male characteristics.18

The above-quoted statement may be compared with the pronouncement

of the Court in Silverio in a footnote: [m]oreover, petitioners female anatomy is

all man-made. The body that he inhabits is a male body in all aspects other than

what the physicians have supplied.19 Taken together, Silverio and Cagandahan

suggest that, insofar as the Supreme Court is concerned, there is a distinction

between a natural and a man-made sex change, wherein the former will

warrant a change of name and sex while the latter will not. This attitude is

undeviating from the Courts repeated practice of refusing to rule on the basis of

its own judgment.

Id. at 76.

Id. at 76-77.

18 Id. at 87.

19 Silverio, 537 SCRA at 392 n.31.

16

17

2014]

A COMMENTARY ON LGBT JURISPRUDENCE

941

In a more recent case promulgated on April 8, 2010, Ang Ladlad LGBT

Party v. Commission on Elections,20 the advocacies of the LGBT community was

raised for the first time in a legal forum. The LGBTs right to political

representation was asserted by Ang Ladlad LGBT Party on behalf of its

estimated 670,000 members and 34 affiliate organizations.21 While the Court

directed the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) to grant Ang Ladlads

petition for registration, the decision fell short of recognizing the LGBT

community as a distinct class of individuals who are discriminated against and

therefore entitled to a specific set of rights. By failing to do so, the Court missed

the opportunity to set a precedent on the extent of LGBT rights and create

positive (or negative) expectations on the future attitude of the Court in deciding

LGBT cases. Notwithstanding the lack of an explicit declaration that the case

was sui generis, it may be said that it was in fact the intention of the Court to

make it one.

In that case, Ang Ladlad, an organization composed of men and women

who identify themselves as LGBT, applied for registration as a party-list before

the COMELEC. Ang Ladlad claimed that it complied with the guidelines laid

down by the Supreme Court in Ang Bagong Bayani-OFW Labor Party v. Commission

on Elections,22 particularly that (1) the LGBT community is a marginalized and

underrepresented sector and (2) Ang Ladlad has a platform of governance that

will contribute to the formulation and enactment of appropriate legislation:

As a party-list organization, Ang Ladlad is willing to research,

introduce, and work for the passage into law of legislative measures

under the following platform of government:

G.R. No. 190582, 618 SCRA 32, Apr. 8, 2010.

Abra Gay Association, Aklan Butterfly Brigade (ABB) Aklan, Albay Gay

Association, Arts Center of Cabanatuan City Nueva Ecija, Boys Legion Metro Manila,

Cagayan de Oro People Like Us (CDO PLUS), Cant Live in the Closet, Inc. (CLIC) Metro

Manila, Cebu Pride Cebu City, Circle of Friends, Dipolog Gay Association Zamboanga del

Norte, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Youth Association (GABAY), Gay and Lesbian Activists

Network for Gender Equality (GALANG) Metro Manila, Gay Mens Support Group (GMSG)

Metro Manila, Gay United for Peace and Solidarity (GUPS) Lanao del Norte, Iloilo City Gay

Association Iloilo City, Kabulig Writers Group Camarines Sur, Lesbian Advocates

Philippines, Inc. (LEAP), LUMINA Baguio City, Marikina Gay Association Metro Manila,

Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) Metro Manila, Naga City Gay Association Naga

City, ONE BACARDI, Order of St. Aelred (OSAe) Metro Manila, PUP LAKAN, RADAR

PRIDEWEAR, Rainbow Rights Project (R-Rights), Inc. Metro Manila, San Jose del Monte Gay

Association Bulacan, Sining Kayumanggi Royal Family Rizal, Society of Transexual Women

of the Philippines (STRAP) Metro Manila, Soul Jive Antipolo, Rizal, The Link Davao City,

Tayabas Gay Association Quezon, Womens Bisexual Network Metro Manila, and

Zamboanga Gay Association Zamboanga City.

22 G.R. No. 147589, 359 SCRA 698, June 26, 2001.

20

21

942

PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL

[VOL. 88 : 937

a) introduction and support for an anti-discrimination bill that

will ensure equal rights for LGBTs in employment and civil

life;

b) support for LGBT-related and LGBT-friendly businesses that

will contribute to the national economy;

c) setting up of micro-finance and livelihood projects for poor

and physically challenged LGBT Filipinos;

d) setting up of care centers that will take care of the medical,

legal, pension, and other needs of old and abandoned

LGBTs. These centers will be set up initially in the key cities

of the country; and

e) introduction and support for bills seeking the repeal of laws

used to harass and legitimize extortion against the LGBT

community.23

In support of its averment of marginalization, Ang Ladlad argued that

the LGBT community is a victim of exclusion, discrimination and violence

because of its members sexual orientation and gender identity. The Second

Division of the COMELEC dismissed Ang Ladlads petition on moral and

religious grounds, citing passages from the Bible and the Koran. This decision

was later upheld by the COMELEC on a motion for reconsideration.

On a petition for certiorari, the Supreme Court directed the COMELEC

to grant Ang Ladlads application. In the en banc decision penned by Justice Del

Castillo, the Court ruled in favor of Ang Ladlad based on its compliance with

the requirements of the Constitution and of Republic Act No. 794124 and the

validity of its exercise of freedom of expression and of association.

First, the Court said that Ang Ladlad had sufficiently demonstrated its

compliance with the legal requirements for accreditation25 and that the

COMELECs denial based on public morals and religion had no legal mooring.

In relation to equal protection, the Court applied the rational basis test in ruling

that moral disapproval of an unpopular minority [] is not a legitimate state

interest that is sufficient to satisfy rational basis26 and concluded that laws of

general application should apply with equal force to LGBTs, and they deserve to

participate in the party-list system on the same basis as other marginalized and

under-represented sectors.27 In effect, the Court eradicated the class created by

the COMELEC that was based on the alleged immorality; at the same time, it

Ang Ladlad, 618 SCRA at 47 n.7.

An Act Providing For The Election Of Party-List Representatives Through The

Party-List System, And Appropriating Funds Therefor.

25 Ang Ladlad, 618 SCRA at 58.

26 Id. at 64.

27 Id. at 64-65.

23

24

2014]

A COMMENTARY ON LGBT JURISPRUDENCE

943

denied that the LGBT is a special class. No discrimination against or in favor of

the LGBT was sanctioned by the Court.

In rebuttal of the OSGs position that LGBT is a separate class, the

Court elaborated:

We are not prepared to single out homosexuals as a separate class

meriting special or differentiated treatment. We have not received

sufficient evidence to this effect, and it is simply unnecessary to make

such a ruling today. Petitioner itself has merely demanded that it be

recognized under the same basis as all other groups similarly situated,

and that the COMELEC made an unwarranted and impermissible

classification not justified by the circumstances of the case.28

Second, the Court declared that the organization of Ang Ladlad was a

legitimate exercise of the LGBTs freedom of expression and of association.

Under our system of laws, every group has the right to promote its

agenda and attempt to persuade society of the validity of its position

through normal democratic means. It is in the public square that

deeply held convictions and differing opinions should be distilled and

deliberated upon.29

***

[H]omosexual conduct is not illegal in this country. It follows that

both expressions concerning ones homosexuality and the activity of

forming a political association that supports LGBT individuals are

protected as well.30

***

European and United Nations judicial decisions have ruled in

favor of gay rights claimants on both privacy and equality grounds,

citing general privacy and equal protection provisions in foreign and

international texts. To the extent that there is much to learn from

other jurisdictions that have reflected on the issues we face here, such

jurisprudence is certainly illuminating. These foreign authorities, while

not formally binding on Philippine courts, may nevertheless have

persuasive influence on the Courts analysis.31

Id. at 65.

Id.

30 Id. at 66.

31 Id. at 67-69.

28

29

944

PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL

[VOL. 88 : 937

While the Court extended protection to the right of LGBTs to express

their sentiments in a political forum, the nature of the protection it extended

seemed to suggest that being an LGBT is akin to holding an opinion. This is

contrary to the fact that being an LGBT goes into the very nature of an

individuals lifewell past the point of opinions and personal advocacies. The

tailend of the Courts statement that acknowledged the recognition of LGBT

rights in foreign jurisdictions was tempered by the qualification that such were

illuminating at best. The import, therefore, of these statements is that in the

Philippines, LGBT rights on an institution level are limited to freedom of

expression and association. Any uprising of hope that this decision had laid the

groundwork for substantial progress in the field of LGBT rights in the eyes of

the law as affirmed by the Court will have been sufficiently sobered by the

Courts disclaimer:

[N]one of this suggests the impending arrival of a golden age for gay

rights litigants. It well may be that this Decision will only serve to

highlight the discrepancy between the rigid constitutional analysis of

this Court and the more complex moral sentiments of Filipinos. We

do not suggest that public opinion, even at its most liberal, reflect a

clear-cut strong consensus favorable to gay rights claims and we

neither attempt nor expect to affect individual perceptions of

homosexuality through this Decision.32

The import of this statement, at the very best, is that the Court remains

undecided on the issue of LGBT rights. A negative take on the aforementioned

statement, since it was couched in negative terms, would be that the attitude of

the Court in future LGBT cases will likewise be negative. Given another LGBT

case, the Court may very well rule in favor of, or against, the LGBT litigant.

Such ambivalent attitude seems to be consistent with the Silverio and Cagandahan

cases.

In all three of the cases discussed, the Court had what appeared to be

ample opportunities to discuss in greater detail the specific rights due to LGBT

groups and individuals under the law. At first blush, it is natural to feel that at

the very least, the Court should haveeven if such statements would have to be

considered as obitertouched upon the issue of what the status of LGBT rights

is under its interpretation of the current law. Yet the decisions of the Court are,

for lack of a better term, sanitized of any indication of their present inclinations

as regards the topic of LGBT rights. The Court has consistently deflected the

issue of LGBT rights under the law whenever it has appeared before it. This also

32

Id. at 72-73.

2014]

A COMMENTARY ON LGBT JURISPRUDENCE

945

is initially perplexing because while the Court maintains a taciturn faade as

regards the issue, it has, in the same breath, recognized the trend in foreign

jurisdictions in favor of granting and expanding LGBT rights. Notably, at

around the time that these decisions were written, the Yogyakarta Principles on

the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation

and gender identity was gaining international recognition. Given the existence of

local cases that were intimately related to the issue of LGBT rights and

international recognition of the same, the question to be asked is this: why has

the Court deliberately maintained its silence?

The likeliest explanation for the Courts reticence is the concept of

judicial restraint. The case of Francisco v. House of Representatives33 provides the

requirements that the Court must deem to have been fulfilled before it exercises

its power of judicial review, namely:

1. Actual case or controversy calling for the exercise of judicial

power[;]

2. The person challenging the act must have standing to

challenge; he must have a personal and substantial interest in the

case such that he has sustained, or will sustain, direct injury as a

result of its enforcement[;]

3. The question of constitutionality must be raised at the earliest

possible opportunity[; and]

4. The issue of constitutionality must be the very lis mota of

the case.34

While this enumeration of elements is usually applied in cases where the issue is

whether or not the Court may look into the constitutionality of an act of the

other two branches of government, its general rationale is that the Court will

not, as a rule, settle the issue of a case on the basis of its own judgment and

proclivities when it may be settled on the basis of justifications that are, within

the judicial context, neutral and objectivelaws, for example.

Applying these elements to the three reviewed cases, it is clear that while

the first two elements may have been met for the Court to exercise its power of

judicial review over the issue of LGBT rights, the last two elements have not

been satisfied. The issue of LGBT rights was never explicitly raised nor was the

33

34

G.R. No. 160261, 415 SCRA 44, Nov. 10, 2003.

Id.

946

PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL

[VOL. 88 : 937

determination of those rights necessary in order for the Court to arrive at a

judgment that was in consonance with exisiting laws. Resultantly, finding fault

with the decision of the Supreme Court to adhere to the principle of judicial

restraint in this context appears to be an exercise in vain.

In spite of the fact that the Supreme Court is justified in not delving any

further into the issue of LGBT rights in the cases that they have heretofore

decided, it is still necessary to probe what little jurisprudence exists as regards

these rights because it is only a matter of time before the Court will have to pass

upon these issues. As of the time of this case reviews writing, the brutal murder

of Jennifer Laude has placed the issue of LGBT rights at the center of public

attention and presents a unique commingling of the various branches of law

under the shadow of LGBT rights. A cursory examination of the issues involved

reveals that it involves international, criminal, and civil law. As such, it is

necessary to synthesize what the Court has said (or not said) regarding LGBT

rights.

First, the silence of the Supreme Court regarding LGBT rights should

not be automatically intepreted as a portent of unfavorable rulings when its

justices finally define LGBT rights within what the law may provide. There is a

slight but not insignificant difference between saying that something is

impossible and saying that something is not possible at the moment. To our

minds, it is the latter that the Supreme Court has regularly implied in its

decisionsan errant biblical quotation notwithstanding. It is not unlikely that

the Court is merely waiting for something to compel them to exercise their

adjudicatory authority over the issue of LGBT rights. It may be a new piece of

legislation: the 2014 UNDP-USAID Philippines Country LGBT report

specifically mentions the absence of an anti-discrimination bill in Philippine

law.35 Alternatively, it could conceivably be a novel argument based on existing

laws that gives the Court no opportunity deflect or sidestep the issue. In

retrospect, the Courts refusal to grant the petition in Silverio on the basis of

equity may ultimately work to the advantage of LGBT advocates because a

ruling on the basis of such is easily assailable and far from secure.

Second, based on the rulings of the Court in the three reviewed cases, it

is clear that they are separate pieces of jurisprudence that are incapable of

coming together to form an unbroken string of precedents. Each was decided

solely within the boundaries of each case and, as earlier noted, no decision spent

35 UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME & USAID, BEING LGBT IN ASIA:

THE PHILIPPINES COUNTRY REPORT 8, 22, 23 (2014), available at http://www.usaid.gov/sites/

default/files/documents/1861/2014%20UNDP-USAID%20Philippines%20LGBT%20Country

%20Report%20-%20FINAL.pdf.

2014]

A COMMENTARY ON LGBT JURISPRUDENCE

947

a word more than what was necessary in order to arrive at their respective

rulings. In fact, it may be reasonably argued that, since the manner of deciding

the three reviewed cases was so insulated from the manner in which the other

two were decided, re-arranging the chronological order of these cases would not

have made any substantial difference as regards the Courts final ruling in each

of them. In other words, any new case concerning LGBT rights will exist in the

same way that these three cases exist in relation to one anotherin total

isolation. This may prove to be favorable to the proponents of LGBT rights

because it means that the Court will grant any subsequent case a clean slate

without any favor and more importantly, without any prejudice.

In conclusion, the prevailing social circumstances point to the

inevitability that, sooner or later, the Court will have to definitively weigh in on

the issue of LGBT rights. The intent of this case review is to impart a sense of

hope that is as slight as it is undaunted that the Court, when finally called upon

to pass on the issue of LGBT rights, will rule in a manner in consonance with

the interests of a group which has, for too long, struggled to assert its

acceptability. As then Chief Justice Puno enunciated in his concurring opinion in

Ang Ladlad, a person's sexual orientation is so integral an aspect of one's

identity.36 To our knowledge, it has never been the practice of the Supreme

Court to deprive a person of anything integral to the existence of his or her

identity.

- o0o -

36

Ang Ladlad, 618 SCRA 32, 103 (Puno, C.J., concurring). (Citation omitted.)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Globalist's Plan To Depopulate The PlanetDokumen16 halamanGlobalist's Plan To Depopulate The PlanetEverman's Cafe100% (5)

- Stemming The Rise of Islamic Extremism in BangladeshDokumen6 halamanStemming The Rise of Islamic Extremism in Bangladeshapi-3709098Belum ada peringkat

- Consumer Guide LPG CylindersDokumen2 halamanConsumer Guide LPG CylinderscmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- MODULE 4 - Session 4. Gender-Sensitive and Child-Friendly ApproachDokumen32 halamanMODULE 4 - Session 4. Gender-Sensitive and Child-Friendly ApproachEvelyn Agustin BlonesBelum ada peringkat

- Privacy, Technology and School Safety DebateDokumen4 halamanPrivacy, Technology and School Safety Debatemonivmoni5Belum ada peringkat

- ADR Operations Manual - AC No 20-2002Dokumen3 halamanADR Operations Manual - AC No 20-2002Anonymous 03JIPKRkBelum ada peringkat

- Loan AgreementDokumen2 halamanLoan AgreementmynonaBelum ada peringkat

- Books For Practice CourtDokumen1 halamanBooks For Practice Courtcmdelrio100% (1)

- AMSCO Guided Reading Chapter 8Dokumen9 halamanAMSCO Guided Reading Chapter 8Raven H.0% (1)

- Bjmpslai Loan Application Form New - Jan2023Dokumen3 halamanBjmpslai Loan Application Form New - Jan2023Mae Loudy Arendon100% (1)

- 252 - People v. JacintoDokumen3 halaman252 - People v. Jacintoalexis_beaBelum ada peringkat

- Ra 9344Dokumen1 halamanRa 9344thedoodlbotBelum ada peringkat

- Access To Outside Communication 1Dokumen6 halamanAccess To Outside Communication 1Sandy Celine100% (1)

- No Homework PolicyDokumen1 halamanNo Homework PolicyJimBoy LomochoBelum ada peringkat

- BJMP Provident Fund FormDokumen1 halamanBJMP Provident Fund FormGeneris SuiBelum ada peringkat

- BJMPRO1 commends Balungao District Jail staff for CRS activitiesDokumen4 halamanBJMPRO1 commends Balungao District Jail staff for CRS activitiesBjmp BalungaoBelum ada peringkat

- Issuance of Local Police ClearanceDokumen1 halamanIssuance of Local Police Clearancejetty latrasBelum ada peringkat

- Declaration of Presumptive Death Strict Standard Under Art 41Dokumen12 halamanDeclaration of Presumptive Death Strict Standard Under Art 41Onireblabas Yor OsicranBelum ada peringkat

- Anti-Rape Law of 1997 (RA 8353) and Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998 (RA 8505)Dokumen20 halamanAnti-Rape Law of 1997 (RA 8353) and Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998 (RA 8505)Chellie Pine MerczBelum ada peringkat

- Duty StatusDokumen5 halamanDuty StatusJomer Ly CadiaoBelum ada peringkat

- The Enhancement of Police Strategy and Security inDokumen6 halamanThe Enhancement of Police Strategy and Security inJovie Masongsong100% (1)

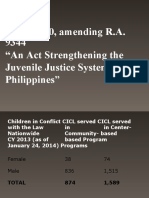

- R.A. 10630, Amending R.A. 9344 "An Act Strengthening The Juvenile Justice System in The PhilippinesDokumen16 halamanR.A. 10630, Amending R.A. 9344 "An Act Strengthening The Juvenile Justice System in The PhilippinesNur SanaaniBelum ada peringkat

- Community's Perception Towards Women Deprived of LibertyDokumen6 halamanCommunity's Perception Towards Women Deprived of LibertyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- SKDokumen18 halamanSKchada labendiaBelum ada peringkat

- IRR For RA 8042Dokumen18 halamanIRR For RA 8042Stephano HawkingBelum ada peringkat

- Lcat VawcDokumen20 halamanLcat VawcMikshiBelum ada peringkat

- PPE-not-recognized-as-assetsDokumen5 halamanPPE-not-recognized-as-assetsbimbyboBelum ada peringkat

- Guide Leadership PDokumen4 halamanGuide Leadership Pvictor yuldeBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis Reflections-on-restorative-justice-in-the-Philippines PDFDokumen4 halamanThesis Reflections-on-restorative-justice-in-the-Philippines PDFGiuliana FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Barangay Justice SystemDokumen41 halamanBarangay Justice SystemAaron ValdezBelum ada peringkat

- Special Penal Laws: Shien CasañaDokumen65 halamanSpecial Penal Laws: Shien CasañacharryohBelum ada peringkat

- Cabadbaran City Ordinance No. 2011-025Dokumen7 halamanCabadbaran City Ordinance No. 2011-025Albert Cong100% (1)

- IFUGAO-Rape CaseDokumen2 halamanIFUGAO-Rape CaseChill RiderBelum ada peringkat

- 08-DepEd2016 Part1-Notes To FSDokumen90 halaman08-DepEd2016 Part1-Notes To FSbolBelum ada peringkat

- Federalism to Empower Regions and Drive GrowthDokumen8 halamanFederalism to Empower Regions and Drive GrowthariesBelum ada peringkat

- DILG MC 2023-025:: Guidelines in The Implementation of The Buhay Ingatan, Droga'Y Ayawan ProgramDokumen34 halamanDILG MC 2023-025:: Guidelines in The Implementation of The Buhay Ingatan, Droga'Y Ayawan ProgramAllan AripBelum ada peringkat

- Affidavit Paniza (Rape)Dokumen10 halamanAffidavit Paniza (Rape)Hadji HrothgarBelum ada peringkat

- People vs. Vicente SalvadorDokumen2 halamanPeople vs. Vicente SalvadorMarie PadillaBelum ada peringkat

- PI DigestDokumen21 halamanPI DigestSheerlan Mark J. QuimsonBelum ada peringkat

- Soria v. Desierto: 153524-25: January 31, 2005: J. Chico-Nazario: Second Division: Decision: January 2005 - Philipppine Supreme Court DecisionsDokumen18 halamanSoria v. Desierto: 153524-25: January 31, 2005: J. Chico-Nazario: Second Division: Decision: January 2005 - Philipppine Supreme Court DecisionsVal SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Implementation of RA 10586 (Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013)Dokumen8 halamanImplementation of RA 10586 (Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013)IJELS Research JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Honors NightDokumen3 halamanHonors NightJV DeeBelum ada peringkat

- BIDADokumen1 halamanBIDALGMED DILG IV-ABelum ada peringkat

- MADAC ResolutionDokumen2 halamanMADAC ResolutionAnnabelle BabalconBelum ada peringkat

- Flowchart of Remedies (NIRC)Dokumen3 halamanFlowchart of Remedies (NIRC)Lorelyn FBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis On Detention PDFDokumen21 halamanThesis On Detention PDFIrwin Ariel D. MielBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 Revised Rule On Children in Conflict With The LawDokumen21 halaman2019 Revised Rule On Children in Conflict With The LawA Thorny RockBelum ada peringkat

- Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act OF 2006 (R.A. 9344) IMPLEMENTATIONDokumen42 halamanJuvenile Justice and Welfare Act OF 2006 (R.A. 9344) IMPLEMENTATIONRNJBelum ada peringkat

- Memorandum: Cesar C Calmada, MacrimDokumen3 halamanMemorandum: Cesar C Calmada, MacrimApril Delos Reyes TitoBelum ada peringkat

- Tanim Bala and Tanim Droga - GRP 3 HR - Consolidated PDFDokumen82 halamanTanim Bala and Tanim Droga - GRP 3 HR - Consolidated PDFRaamah DadhwalBelum ada peringkat

- Voters EducationDokumen31 halamanVoters Educationlito77Belum ada peringkat

- MOA Re Capacitating Kasurog Care Stakeholders Through Education and Trainnings LGU OASDokumen4 halamanMOA Re Capacitating Kasurog Care Stakeholders Through Education and Trainnings LGU OASJohn B BarbonioBelum ada peringkat

- Court PillarDokumen43 halamanCourt PillarChane ReponteBelum ada peringkat

- Legal Medicine Report On Impotency and SterilityDokumen22 halamanLegal Medicine Report On Impotency and SterilityAnna L. Ilagan-MalipolBelum ada peringkat

- Contract of LeaseDokumen3 halamanContract of LeaseDianneBelum ada peringkat

- Youth Perceptions of SuffrageDokumen17 halamanYouth Perceptions of SuffrageEvan Mae LutchaBelum ada peringkat

- Lydc - Notice of Meeting 03 - 16 - 2019Dokumen1 halamanLydc - Notice of Meeting 03 - 16 - 2019Si ChiBelum ada peringkat

- Technological Institute of the Philippines whistle-blower case studiesDokumen6 halamanTechnological Institute of the Philippines whistle-blower case studiesStephany ChanBelum ada peringkat

- Application Form For The National Bureau of InvestigationDokumen8 halamanApplication Form For The National Bureau of InvestigationlossesaboundBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence ReviewerDokumen53 halamanEvidence ReviewerBonnie Catubay100% (1)

- Certification Coc EarnedDokumen2 halamanCertification Coc EarnedYvonie CabugatanBelum ada peringkat

- CS Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience Sheet LAURENTEDokumen3 halamanCS Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience Sheet LAURENTESamm LaurenBelum ada peringkat

- Against Divorce ArticlesDokumen11 halamanAgainst Divorce ArticlesRikki Marie PajaresBelum ada peringkat

- Juvenile Justice and Juvenile Delinquency System: Asmundia@sfxc - Edu. PHDokumen3 halamanJuvenile Justice and Juvenile Delinquency System: Asmundia@sfxc - Edu. PHJayson GeronaBelum ada peringkat

- Pagadian City Council Amends Youth Internet LawDokumen4 halamanPagadian City Council Amends Youth Internet LawGrassy GraceBelum ada peringkat

- Rule 103 and 108Dokumen7 halamanRule 103 and 108Joel MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- PioneerDokumen5 halamanPioneercmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Conflicts ReviewerDokumen165 halamanConflicts ReviewercmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- IPL Del Rio 05232016Dokumen5 halamanIPL Del Rio 05232016cmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Political Velasco CasesDokumen41 halamanPolitical Velasco CasescmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Ownership of A Trademark Is Not Based On An Earlier Filing Date (EY Vs Shen Dar, 2010)Dokumen5 halamanOwnership of A Trademark Is Not Based On An Earlier Filing Date (EY Vs Shen Dar, 2010)cmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Political Velasco CasesDokumen41 halamanPolitical Velasco CasescmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- JOAQUIN T. SERVIDAD, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission, Innodata Philippines, Inc./ Innodata CORPORATION, TODD SOLOMON, RespondentsDokumen7 halamanJOAQUIN T. SERVIDAD, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission, Innodata Philippines, Inc./ Innodata CORPORATION, TODD SOLOMON, RespondentscmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- RP-China Final Arbitration Award (J. Carpio)Dokumen31 halamanRP-China Final Arbitration Award (J. Carpio)Gai Flores100% (1)

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokumen36 halamanBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Bermudez PDFDokumen2 halamanBermudez PDFcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Transpo CasesDokumen31 halamanTranspo CasescmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDokumen32 halamanBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- What Are The Requisites of A Lawful Strike or Lockout?Dokumen4 halamanWhat Are The Requisites of A Lawful Strike or Lockout?cmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Adr ArticleDokumen6 halamanAdr ArticlecmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Transpo CasesDokumen31 halamanTranspo CasescmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Torts Compilation - Standard of ConductDokumen143 halamanTorts Compilation - Standard of ConductLeomard SilverJoseph Centron LimBelum ada peringkat

- Transpo Friday DigestDokumen14 halamanTranspo Friday DigestcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Specpro FinalsDokumen36 halamanSpecpro FinalscmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Baca LingDokumen18 halamanBaca LingcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- ADR DefinitionsDokumen7 halamanADR DefinitionscmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Conflicts of Law Saturday OrigDokumen27 halamanConflicts of Law Saturday OrigcmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Torts September 9Dokumen139 halamanTorts September 9cmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- G R No L 59825Dokumen8 halamanG R No L 59825cmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Example One Way Non Disclosure Agreement PDFDokumen3 halamanExample One Way Non Disclosure Agreement PDFhahalerelor100% (1)

- Affidavit of LossDokumen1 halamanAffidavit of LosscmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Records Management Bulletin: A Common Sense Guide To E-Mail EtiquetteDokumen2 halamanRecords Management Bulletin: A Common Sense Guide To E-Mail EtiquettecmdelrioBelum ada peringkat

- Garcia Vs LacuestaDokumen2 halamanGarcia Vs Lacuestalen_dy010487Belum ada peringkat

- AITC Candidates For WB AE 2021Dokumen13 halamanAITC Candidates For WB AE 2021NDTV80% (5)

- 1392 5105 2 PB PDFDokumen7 halaman1392 5105 2 PB PDFNunuBelum ada peringkat

- Bengali Journalism: First Newspapers and Their ContributionsDokumen32 halamanBengali Journalism: First Newspapers and Their ContributionsSamuel LeitaoBelum ada peringkat

- Sexism in MediaDokumen8 halamanSexism in Mediaapi-320198289Belum ada peringkat

- B005EKMAZEThe Politics of Sexuality in Latin America: A Reader On Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights - EBOKDokumen948 halamanB005EKMAZEThe Politics of Sexuality in Latin America: A Reader On Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights - EBOKWalter Alesci-CheliniBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of 'Travel and Drugs in Twentieth-Century LiteratureDokumen4 halamanAnalysis of 'Travel and Drugs in Twentieth-Century LiteratureMada AnandiBelum ada peringkat

- Belgrade Insight - February 2011.Dokumen9 halamanBelgrade Insight - February 2011.Dragana DjermanovicBelum ada peringkat

- Disability Embodiment and Ableism Stories of ResistanceDokumen15 halamanDisability Embodiment and Ableism Stories of ResistanceBasmaMohamedBelum ada peringkat

- DIP 2021-22 - Presentation Schedule & Zoom LinksDokumen5 halamanDIP 2021-22 - Presentation Schedule & Zoom LinksMimansa KalaBelum ada peringkat

- Political System ChinaDokumen4 halamanPolitical System ChinaSupreet SandhuBelum ada peringkat

- Skills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitDokumen4 halamanSkills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitKim Boyles Fuentes100% (1)

- Perang Inggeris Burma PDFDokumen12 halamanPerang Inggeris Burma PDFMaslino JustinBelum ada peringkat

- I of C Globally: VOL 13 No. 4 JUL 10 - MAR 11Dokumen44 halamanI of C Globally: VOL 13 No. 4 JUL 10 - MAR 11saurabhgupta4378Belum ada peringkat

- By Senator Rich Alloway: For Immediate ReleaseDokumen2 halamanBy Senator Rich Alloway: For Immediate ReleaseAnonymous CQc8p0WnBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To The Characters in The Buddha of SuburbiaDokumen5 halamanA Guide To The Characters in The Buddha of SuburbiaM.ZubairBelum ada peringkat

- DETERMINE MEANING FROM CONTEXTDokumen2 halamanDETERMINE MEANING FROM CONTEXTKevin SeptianBelum ada peringkat

- People Vs YauDokumen7 halamanPeople Vs YauMark DungoBelum ada peringkat

- Difference Between Home and School Language-1Dokumen20 halamanDifference Between Home and School Language-1Reshma R S100% (1)

- It ACT IndiaDokumen3 halamanIt ACT IndiarajunairBelum ada peringkat

- Inversion (Theory & Exercises)Dokumen8 halamanInversion (Theory & Exercises)Phạm Trâm100% (1)

- Philippine Declaration of IndependenceDokumen2 halamanPhilippine Declaration of Independenceelyse yumul100% (1)

- Crash Course 34Dokumen3 halamanCrash Course 34Gurmani RBelum ada peringkat

- The Fall of BerlinDokumen4 halamanThe Fall of Berlineagle4a4Belum ada peringkat

- Cover Letter TourismDokumen2 halamanCover Letter TourismMuhammad IMRANBelum ada peringkat

- (G.R. No. 115245, July 11, 1995)Dokumen3 halaman(G.R. No. 115245, July 11, 1995)rommel alimagnoBelum ada peringkat

- The Rise and Goals of the Katipunan Secret SocietyDokumen13 halamanThe Rise and Goals of the Katipunan Secret SocietyIsabel FlonascaBelum ada peringkat

- Research EssayDokumen29 halamanResearch Essayapi-247831139Belum ada peringkat