1 s2.0 S0263786309000167 Main

Diunggah oleh

Yasir ArafatDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1 s2.0 S0263786309000167 Main

Diunggah oleh

Yasir ArafatHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

Major challenges to the successful implementation

and practice of programme management

in the construction environment:

A critical analysis

Zayyana Shehu a,*, Akintola Akintoye b

a

School of Built and Natural Environment, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, United Kingdom

b

School of Built and Natural Environment, University of Central Lancashire, Preston PR1 2HE, United Kingdom

Received 10 October 2008; received in revised form 29 December 2008; accepted 5 February 2009

Abstract

For the construction industry to survive the current turbulence in the economic atmosphere, it has the option of integrating new initiatives to march the uncertainties. Programme management is seen as an ecient vehicle to successfully deliver the improvements and

changes. However, the implementation of any new system or change initiatives has always been a challenging task; some of these challenges can be faced during the implementation or at practice stage. Programme management is not exempt from such challenges, in order

to successfully implement and practice programme management, the knowledge of the major challenges associated to eective implementation and practice should not be left to serendipity or sagacity. Due to the lack of clarity surrounding programme management in the

construction industry, the understanding of these major challenges remains vague. To provide a deeper insight into the major challenges

to implementation and practice of construction programme management, this paper conducts both a pragmatic and theoretical study by

triangulating literature, industrial questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews. The research was conducted in the UK construction industry and other programme management sectors to analyse and exploit the knowledge of these challenges for eective implementation and practice of construction programmes. A total of 119 usable questionnaires were received and 17 semi-structured interviews

were conducted, analysed and synthesised to provide a broader view on the major challenges and how to eectively implement and practice construction programmes.

2009 Elsevier Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Challenges; Implementation; Practice; Programme management

1. Introduction

There is indication that organisations are getting more

aware and interested in the discipline of programme management [1], but [2,3] explained that lack of clarity and

understanding has contributed to a lack of understanding

and interest in programme management. To fully comprehend, it is essential to give an overview of the term programme management. Many denitions of the term

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 7729355179.

E-mail address: zayyana.shehu@gmail.com (Z. Shehu).

0263-7863/$36.00 2009 Elsevier Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.02.004

programme management exist, yet they all highlight common attributes of the selection, planning and overall management of a portfolio of projects to achieve a set of

business objectives. In addition, some of the denitions

also indicate the ecient execution of the portfolio of projects within a controlled environment [4,5], so that they realise maximum benet for the resulting business operations

[6]. In other words, [7] denes programme management as

the management of large capital projects. Lycett et al. [8]

dene programme management as the integration and

management of a group of related projects with the intent

of achieving benets that would not have been realised had

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

the projects been managed independently. While connected, this is distinct from portfolio management, whereas

[9] denes programme management as the management of

a portfolio of projects which call upon the same resources

and concentrates on the next stage of development it

involves planning each individual project planned and

resourced. In other words, programmes involve directing

a portfolio of projects, one huge project (mega project)

[9,10], and managing a series of projects for the same client

which benet from a consolidated approach.

The plurality and diversity of denitions for programme

management can be associated with its origin and lack of

understanding. Milosevic et al. [3] are condent that a fair

amount of confusion exists among organisations about

what programme management stands for, and lack sucient literature to accurately describe it. Subsequently,

[11] also observe that when individuals involved in programmes meet one another they spend time trying to

understand what the other means by the term programme

management. These ambiguities surrounding the nature

and practice of programme management remain, resulting

in diverse understandings and denitions.

Having seen how writers dene the term programme

management, this research understands that the maturity

of project management and its limitations gave birth to

the phenomenon of programme management as a de facto

means of aligning, coordinating and managing a portfolio

of projects to deliver benets which individual projects

would not have been able to deliver independently [12].

Hence denes programme management as an integrated,

structured-framework to co-ordinate, align, and allocate

resources, as well as plan, execute and manage a portfolio

of construction projects simultaneously to achieve optimum benets that would not have been realised had the

projects been managed separately.

2. Literature review

Young [13] asserts that todays construction industry

operates in a climate of widespread economic uctuations,

population and migration growth, and the growing pressure from global economic instability. He further stresses

that regions and economies of the world are increasingly

interdependent and new challenges arise every day that

lead to major shifts in the context of the market place.

Despite the changes and pressure, the UK construction

industry is ranked among the strongest in the world, with

its output classied in the global top-ten according [14,15].

A mass migration from project management to programme management becomes imminent [1,16] some major

challenges are inevitable and their knowledge will be essential. For programme management to be understood and

accepted in the construction industry, it would be benecial

if it were broken down (programme management) into

more comprehendible components. Hence, this research

explores and focuses on the challenges during the implementation and practice stages of construction programmes.

27

The thorough literature review in programme management

established some major challenges which include but is

not limited to the following.

3. Lack of commitment from business leaders

Among the many major challenges to the implementation and practice of programme management is the lack

of commitment from the business leaders. Martin and

Nicholls [17] dene commitment as willingness on the part

of individuals to contribute much more to the organisation

than their formal contractual obligation. MerriamWebster denes commitment as an act of committing to a

charge or trust.

Programme management can only be successfully

designed and implemented in any organisation if there is

commitment from the business leaders [18,19]. The top

management approach can be seen in the form of commitment and support, appropriate organisational policy that is

accepted by every employee in the organisation, and regular management reviews [20]. Fowler and Walsh [21] cited

[22] that if projects (in this case programme) aect a large

part of the organisational resources, the involvement of

senior management is crucial. Lack of interest and involvement among the business leaders can let other activities

take a priority attention that is not favourable to the programme. Hence, [18] believe that a lack of commitment

among business leaders is a major challenge to the successful practice of programme management.

4. Late delivery of projects, lack of cross-functional working,

lack of coordination between projects and lack of alignment

of projects to strategy

Abraham [23] believes that the traditional approach to

success in the construction industry places great emphasis

on the ability to plan and execute projects in time. Companies completing projects in a timely manner within an

established budget and meeting required quality considerations have been considered successful companies. Therefore, if a programme delivers the functional projects late,

this can result in a challenge to the practice of programme

management [3,18].

The alignment, planning, coordination and execution of

the functional projects in a programme are carried out with

a high level of precision, as a problem from one project is

likely to aect the other projects, which in turn can aect

the entire programme. With this level of synergy, a lack

of cross-functional working and coordination in any of

the projects will become a major challenge to the success

of the programme [3,18].

5. Lack of knowledge of portfolio management techniques,

risk management and nancial skills

According to [24] knowledge is an essential strategic

resource in order for a rm to retain sustainable competi-

28

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

tive advantage. As knowledge is created and disseminated

throughout the rm, it has the potential to contribute to

the rms value by enhancing its capability to respond to

new and unusual situations [25]. Lack of knowledge in

managing a portfolio of projects, risk management and

nancial skills is a major challenge to the success of implementing and practicing programme management in the

construction industry [9,18].

6. Lack of cross-functional communication

Generally, eective communication is about exchanging

meaningful information between groups of people with the

aim of inuencing beliefs or actions. OGC [26] states that

communication is central to any change process. The

greater the change, the greater the need for clear communication about the reasons and rationale behind it, the benets expected, the plans implemented and its proposed

eects. Programme management is no dierent; it is aimed

at exchanging timely and useful information with the stakeholders or team. Lack of cross-functional communication

is a major challenge to programme management [6,18,27].

7. Lack of an appropriate way to measure project benets,

lack of resources (human/nancial) to analyse project data

and people constraints

Organisations engage in programme management to

derive the benets that are not available in project management [3,2729]. Lack of appropriate measure or terms of

measurement of benet is a challenge that will face an organisation newly engaged in programme management.

Organisations will be required to establish what type of

benets they want to achieve in programme management.

Even if the benet measure has been established, the

organisation may be faced with the task of providing a sufcient amount of human and nancial resources to analyse

the programme data in view of making decisions.

8. Financial constraints and lack of relevant training

Reiss [9] highlights that putting together and operating a

programme management environment is not a cheap aair,

while [27] explains in the same direction that true cost of a

programme comprises of the cost of resources, infrastructures, materials, premises and equipments and risk exposure, which is only apparent at certain stage of the

programme. Williams and Parr [18] suggest that nancial

constraint may be encountered by the organisations operating programme management. Financial constraints to

procure and sustain a programme can be a major challenge

to its practice.

Programmes are quite complex structures with high level

of coordination and synergy among the cross-functional

projects with many stakeholders of conicting interest

[3,9,27]. Programme may only be successful if its management possess the relevant skills and competency for the

role. Training is essential for the programme members

which without, the organisation will have source and provide [30]. Hence, this research observes that lack of relevant

training can therefore be a major challenge to the practice

of programme management.

9. Research methods

The ndings in this research are through the triangulation of literature review, an industrial questionnaire survey

and semi-structured interviews in the construction industry. In the survey, 1380 postal questionnaires were sent to

the construction industry, using a convenience sampling,

as the target population was not known by the researcher

[3133]. A total of 119 usable completed questionnaires

were received and analysed, the number implies that

around 9% of the total sample contacted has participated

in the study. According to [31], a survey rarely achieves a

response from every contact made. Fellows and Liu [32]

explain that given the increasing number of research projects, collecting data is becoming progressively more dicult. The respondents are being targeted with many

requests for data and they are subsequently becoming

unwilling to spend a lot of time on them and ultimately

refusing to participate in academic surveys. Pathirage

et al. [34] assert that the dichotomy in allocating the blame

for the poor responses in academic surveys appears to be

cyclic and continuum between the academia and the industry. Olomolaiye [25] highlights that lack of understanding

of research area can also lead to poor participation; this

however indicates that there may be a lack of deeper understanding of the term programme management, hence may

justify the low response rate.

To increase the depth and breadth of programme management knowledge, responses were also collected, analysed and synthesised from other non-construction

programme management organisations in the semi-structured interviews. The sample of the population for the

semi-structured interview was acquired by providing a column in the questionnaire for participants willing to be

interviewed to provide their details; use of snowballing

approach [31] and referral by the programme management

experts [35].

The analysis of data for the semi-structured interview

was conducted using NVivo7. The data was coded using

conceptual approach. It has been indicated that the focus

in conceptual content analysis is based on looking at the

occurrence of selected terms within a text or texts, although

the terms may be implicit as well as explicit [3638]. At the

end of the interview sessions, a total 17 interviews were

conducted with programme management experts. All the

interviews selected, regardless of their sectors, demonstrated a reasonable level of understanding of the construction sector as a result of direct association, through their

stakeholders or colleagues.

The main focus of this research is the construction

industry, but due to a lack of availability of contextual pro-

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

gramme management knowledge and experience within

this sector, the research also took the opportunity to learn

from other sectors. It has been established that knowledge

sharing is essential to increase competitive advantage in the

construction industry [39,40]. The knowledge acquired

from other sectors was then synthesised to develop an

understanding of how to implement and practice programme management within the construction environment.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted to supplement the nding of the literature review and questionnaire survey [41], the other sectors contacted included IT,

telecoms and others as a result of study conducted by the

Association for Project Managers (APM), titled APM

introduction to programme management [1]. The report

indicates that programme management is more popular

in the government sector and in information technology

programmes. Whereas, the most common programmes

were operated in information technology, which constituted 54%, organisational changes 20%, civil engineering

8%, product development 5% and other types of programmes 12% of the overall total.

The semi-structured interview sample consists of a construction programme director working on a City Councils

school projects, overseeing a network of contractors

executing a six high school programme, while the three

programme managers are involved in residential construction, commercial construction and construction civil engineering projects. The other construction interviews

include two project managers working in a programme

management environment and a programme support manager (assisting a programme manager). This study contacted those who are involved with programmes in the

interviews as the programme management knowledge does

not solely lie with the programme managers.

10. Analysis of results

In the rst part, the analysis of results for the qualitative

data was conducted, presented and discussed to provide a

deeper insight into major challenges to the implementation

and practice of programme management, while the second

part presents the analysis of quantitative data analysis.

11. Major challenges to implementation

This section presents the analysis of the semi-structured

interviews data on major challenges to the implementation

of programme management. A question was asked regarding the major challenges facing organisations in implementing programme management and what is anticipated. In

the question, certain factors, such as lack of awareness of

programme management and its benets, convincing directors to implement programme management, organisational

challenges and other challenges have been established as

the sources of the challenges emerged.

It is not unusual to face certain challenges in the transition from one management approach to another [28]. Pro-

29

gramme management is not exempt, and the semistructured interviews revealed the possible major challenges that a potential programme management organisation could face in the process of adoption and

implementation. These challenges are awareness, organisational challenges, and other challenges, such as directors

acceptance.

Based on the conceptual content analysis conducted, on

the structured interviews data, lack of awareness, benets

and nature of programme management ranked among

the major challenges to the successful implementation of

programme management. However, this is not unexpected,

as discussed by [3]; they observed that a lack of knowledge

and awareness of programme management can be associated with its origin in US aerospace and intelligence agencies. Providing awareness may help the prospective

programme management organisations to fully understand

and gain cooperation from the members of the organisation to implement and practice programme management.

Awareness becomes a major challenge with 23 references

in 17 interviews conducted. To overcome lack of awareness

and understanding there is need for both academia and the

industry to provide detailed information on programme

management and its benets.

Having established that awareness is the highest challenge to the implementation of programme management,

the lowest challenge appeared to be getting the directors

to accept the validity of programme management. One of

the construction programme managers interviewed

observed that:

Implementation of programme management has to be

supported by the board of directors through continuous

communication (talks) (awareness) and follow ups, feedbacks from programme managers to the board of directors and clarifying the interfaces and the benets.

Some other challenges may emanate from other aspects,

such as lack of management maturity, stakeholders attitude, etc. while other challenges, such as recognising programme management as a profession, and fear of losing

power by some members of the organisation constitute

another challenge [42].

12. Major challenges to practice of programme management

Having seen the major challenges to implementation of

programme management, this section presents the quantitative data analysis. This section further examines the challenges to the successful practice of programme

management. The data for this was collected from the

UK construction industry using a questionnaire survey.

The total of 119 usable responses received were analysed

to make inferences. Some of the sectors are involved with

construction projects in the form of residential and commercial, civil engineering (road and others), services, etc.

[43,44].

30

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

The data for the major challenges was analysed using

criticality index to rank the challenges; t-test to compare

the responses from the organisations practicing and those

that are not practicing programme management in the

UK construction industry. Prior to proceeding with the

analysis, a Cronbach a reliability analysis was conducted.

The result of the test proves the reliability the data is

a P 0.7 as recommended by [45,46]. Nunnallys [47] suggests that in the early stages of research on predictor tests

or hypothesised measures of a construct, reliability of

a P 0.7 or higher will suce. In this case, a = 0.924.

The aim of conducting the analysis was to identify and

rank the major challenges to the successful practice of programme management in the construction industry criticality index has been widely used in research projects.

Abdul Kadir et al. [48] used the importance index approach

to evaluate the factors aecting construction labour productivity in Malaysian construction projects; [49] used relative importance index method of the attributes of clients

organisations, which may inuence project consultants

performance. Odeh and Bettaineh [50] also used importance to determine causes of construction delay in traditional contracts. Chan and Kumaraswamy [51] also

applied relative importance index in their comparative

study of the causes of time overruns in Hong Kong construction projects, Cheng [52] used importance index in discussing technology foresight. As a result of its popularity,

reliability and eectiveness, this research adapts the

approach to rank the major challenges to the successful

implementation and practice of programme management.

This research uses the formula in [50] due to the clarity,

simplicity and applicability to its data, while the analysis

uses the weighting used by Cheng [52]. Cheng uses the

weighting of the importance from 0.00, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75

and 1 to represent the value of the responses on the Likert

scale. In the approach, the weighting substitutes the position of the Likert scale. The maximum criticality index is

one, any skills and competencies with the highest value

between 0 P 1 is considered critical. In addition, this section will rank the major challenges according to their criticality. The relative criticality index is computed using the

formula below:

P5

i1 W i X i

C P

5

i1 X i

where C is the criticality index. i responses category index = 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 (position on the Likert scale). Wi is

the weight assigned to ith response = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75

and 1, respectively [52]. Xi is the frequency of the ith response given as percentage of the total responses [40].

13. Mean and index analysis for major challenges

It has been observed that mean indexing has been repeatedly and widely used in presenting exploratory and descriptive data analysis and can provide support to the criticality

index in this research. Among many others, [53] use the

standard deviation and mean to discuss the severity diagnosis of productivity problems and analyse reliability.

Ogunlana et al. [54] used the standard deviation and mean

in evaluating the factors and procedures used in matching

project managers to construction projects in Bangkok.

Thite [55] used mean and standard deviation to analyse

the leadership styles in information technology projects.

Raz and Michael [56] used mean and standard deviation

to analyse use and benets of tools for risk management.

Akintoye and MacLeod [57] used mean and standard deviation in risk analysis and management in construction.

This research also uses the same approach to support criticality index to rank the major challenges, the questionnaire ranged from 1 (low) to 5 (high), higher mean scores

reect responses that indicate the higher importance of

the respective challenge.

14. t-Test for major challenges

t-Test is appropriate when there is a dichotomous independence, and wishes to test the dierence of means in this

case, to test mean dierences between samples of the companies practicing and not-practicing programme management in the UK construction industry. As established, ttest may be used to compare the means of a criterion variable for two independent samples or for two dependent

samples, or between a sample mean and a known mean

(one-sample t-test) [58,59]. t-Test analysis has also been

used in many research projects to compare dierent means

of dierent groups. Papastathopoulou et al. [60] used the

approach in evaluating the success of new-to-the-market

versus me-too retail nancial services.

Prior to the analyses of the responses, a t-test was conducted to compare the responses of the organisations practicing programme management and those that are not

practicing programme management to detect any discrepancies. This research employed t-test to compare the means

of the organisations practicing and not practicing programme management. Based on the results of the t-test,

there is no statistical variation in the responses of those

organisations practicing and those not practicing programme management, hence the data was analysed as a

homogeneous set of data. Table 1 presents the exploratory

and inferential data collected.

According to [19], in t-test, if signicance level (q) is

below 0.05 indicates a high degree of dierence of opinion

between groups on that factor (in this case, those practicing

and not-practicing programme management). Pallant [46]

asserts that if q P 0.05, (e.g., 0.06, 0.10), there is no significant dierence between the two groups. There are no signicant statistical variations between the responses of the

group practicing and those who are not practicing programme management; the challenges to the implementation and practice of programme management have been

ranked in the order of their criticality.

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

31

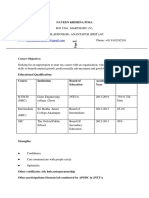

Table 1

Major challenges to successful practice of programme management in the UK construction industry.

Major challenges to programme/multiple projects management

Lack of commitment from business leaders

Late delivery of projects

Lack of knowledge to evaluate risks

Lack of understanding of the role of programme

management in the organisation

Dening clear mission for the programme

Frequent projects scope changes

Conicting project objectives

Lack of cross-functional communication

Lack of programme delivery infrastructure

Lack of clear company strategy

Financial constraints

Lack of coordination between projects

Lack of relevant training

People constraints

Lack of alignment of projects to strategy

Lack of cross-functional working

Initial funding and ongoing operational costs to the organisation

Lack of appropriate way to measure projects benets

A perception among the project community that the programme

will serve as an obstacle to the timely accomplishment of project management

Lack of nancial skills of project/other sta

Lack of understanding of the value proposition that programme management provides

Lack of awareness and associated benets

Lack of resources (human/nancial) to analyse project data

Resistance to organisational change

Lack of knowledge of portfolio management techniques

Disappointment with nal project benets

Too many unrelated projects

Presenting a detailed description of the intended roles of a PMO in the organisation

Total results

Practicing and not-practicing

programme management t-test

CI

Mean

Mean

Practice

Not-practice

0.789

0.772

0.759

0.726

4.155

4.086

4.034

3.905

4.087

4.000

4.022

3.913

4.209

4.149

4.060

3.910

0.4571

0.356

0.821

0.987

0.722

0.722

0.711

0.690

0.684

0.681

0.678

0.670

0.668

0.664

0.660

0.646

0.641

0.638

0.623

3.887

3.888

3.845

3.759

3.737

3.724

3.713

3.681

3.672

3.655

3.640

3.583

3.565

3.552

3.491

3.933

3.783

3.870

3.783

3.689

3.848

3.689

3.717

3.761

3.630

3.689

3.711

3.622

3.652

3.614

3.881

3.970

3.791

3.716

3.758

3.642

3.716

3.627

3.627

3.642

3.621

3.507

3.537

3.478

3.385

0.763

0.299

0.631

0.694

0.708

0.2081

0.885

0.614

0.3641

0.9471

0.706

0.250

0.614

0.283

0.249

0.622

0.622

0.611

0.604

0.593

0.583

0.578

0.567

0.544

3.487

3.487

3.442

3.414

3.371

3.333

3.313

3.267

3.176

3.457

3.511

3.400

3.409

3.326

3.356

3.311

3.261

3.310

3.515

3.463

3.492

3.415

3.388

3.333

3.328

3.254

3.111

0.739

0.786

0.627

0.975

0.717

0.902

0.926

0.968

0.287

Sig.(q)

CI, criticality index; SD, standard deviation; Sig.(q), signicance level; and 1, equal variance not assumed.

Hence the analysis of the results indicate that the major

challenge to the practice of programme management is

lack of commitment from business leaders with criticality

index of 0.789 whereas presenting a detailed description

of the intended roles of a programme management oce

(PMO) in the organisation is the lowest challenge to practicing programme management in the UK construction

industry with 0.544 criticality index. Based on the results

from the criticality ranking of the major challenges of

adoption, the implementation and practice of programme

management in the UK construction industry, commitment from senior management (directors) is crucial to the

success of practicing construction programme management. It is advisable that if the implementation idea did

not come from the management level, there would be a

need to provide a detailed business case for practicing programme management, in order to convince the directors to

accept the idea. This can be in the form of programme

management versus project management challenges; or

short term versus long-term benets. Most of the time,

the directors would want to see the projected benets

before they buy into the idea and support it. It would

not be dicult to secure the support, as long as business

leaders are comfortable with the idea and the projections

are viable and achievable.

In many cases, the business case would have to demonstrate improvement and the justication for the investment;

as programmes are capital and human resource intensive.

In contrast, comparing programme and project management may come out as a choice between long and short

term benets [42]. Some of the benets of programme

management are not immediate and may not directly translate into nancial benets [61]. However, the directors are

expected to weigh the options of short-term benets

against long-term benets within the organisational goals

and objectives. To eectively address this major challenge,

an IT programme director advised that, It is encouraged

that a programme manager should be a senior member of

the organisation who will always have access to the senior

management (directors), and has the seniority to inuence

their decision. Hence, having a programme manager who

is a middle or junior manager will have a seniority barrier

to inuence the company directors.

The second major challenge to the practice of construction programme management is the late delivery of projects. This is no doubt a problem due to the synergistic

32

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

nature of programme management. According to [3], programmes are highly integrated endeavours in which the

action of one project aects the rest of the projects in a programme. The indication in this challenge is the need for

real-time proactive planning; properly planned projects

transcend into an ecient programme. Eective planning

is one of the prerequisites of programme management

and its importance cannot be overemphasised.

The second to last major challenge to the practice of

construction programme management is too many unrelated projects in a programme. This is, however, not surprising, as in reality, the relationship of construction

projects is relative to the planning and other factors, such

as the sharing of resources, facilities and infrastructures

[26,30]. The relationship can be established in multiple facets: planning, supply chain management, resources, funding, execution, etc. The respondents, however, do not see

connecting (relating) projects as a challenge. Whereas the

most insignicant (minor challenge) to practicing programme management is presenting a detailed description

of the intended roles of programme management oce

(PMO) in the organisation as the least of the listed challenges. PMO is the centre of control of programme management, it acts as the centre of planning and

coordination of the activities of the functional projects in

a programme; hence the description of its roles will be relatively easy to make and understand.

To proceed to the next level of reducing the factors for

the benets of trainer or educators by reducing the major

challenges into more manageable components, factor analysis will be conducted.

15. Factor analysis for major challenges to the practice of

programme management

To reduce the list of major challenges into more manageable numbers for support or CPD purposes, factor

analysis was conducted into the major challenges. Prior

to the factor analysis, Bartletts test of sphericity and a

KaiserMeyerOlkin (KMO) test were conducted to help

assess the factorability of the data. Bartletts test of sphericity should be p < .05 to be signicant; whereas KMO index

ranges from 0 to 1 with .6 as a minimum value for a good

factor analysis.

The value of the KMO statistic is 0.863, which, according to [62], is satisfactory for factor analysis. Bartletts test

of sphericity tests the hypothesis that the correlation matrix

is an identity matrix. In this case, the value of the test statistic for sphericity is large (Bartletts test of sphericity = 378) and the associated signicance level is small

(p = 0.000), which suggests that there is no need to eliminate any of the variables for the principal component

analysis.

Having conducted the factorability analysis, factor

extraction tests using Kaisers criterion and Scree plot analysis were conducted. Factor extraction is the determination

of the number of factors necessary to represent the data

[63]. Kaisers test is one of the most commonly used techniques, otherwise known as eigenvalue rule. Using this rule,

only the factors with an eigenvalue of 1.0 or more are

retained for further investigation [46]. Whereas the Scree

test involves plotting each of the eigenvalues of the factors

and inspecting the plot to nd the point at which the shape

of the curve changes direction to become horizontal. Cattell [64] recommends retaining all factors above the elbow

or break in the plot, as these factors contribute to the

explanation of the variance in the data set. The combination of these two techniques was employed in a complementary manner in this research.

Appendix 1 presents the initial and rotated factor matrix

of major challenges to the practice of programme management, the eigenvalues for all the factors in major challenges

to the eective practice of programme management. In the

table, the rst column represents the 28 major challenges

listed; the second column represents the initial eigenvalues

of the respective components (total variance, percentages

and cumulative percentages). Whereas the extraction sums

of square loadings columns represent the factors with more

eigenvalue of 1.0 and above. The factors with eigenvalue of

1.0 and above will proceed to further examination.

Naming the principal factors was done in line with [65]

recommendations, which suggests that the factor names

should be brief (one or two words) and communicate the

nature of the underlying construct. This was done by looking for patterns of similarity between items that load on a

factor. In addition, looking at what items do not load on a

factor, to determine what that factor is not. Also, try

reversing loadings to get a better interpretation [66].

By looking for patterns of similarity between items that

load on a factor, particularly when seeking to validate a

theoretical structure, it is possible to use the factor names

that already exist in the literature. Otherwise, names that

will communicate conceptual structure to others are used.

Looking at what items do not load on a factor to determine

what that factor is not [65]. In line with recommendation of

[65], to name the factors for this research, a questionnaire

was sent to ve programme management experts to validate the naming of the principal factors. The respondents

of the naming survey all agreed with the names as the suitable representation of the principal factors. Takim [67]

observes that there is no rule of thumb in making factors

to fall within the same group as this taken care of by the

rotation technique used.

16. Principal factors

Often, using Kaisers criterion, many components are

extracted. It is important, therefore, to also check the Scree

plot to select and retain factors for the components above

the shoulders of the curve [46,66]; in this case six factors are

identied as shown in Appendix 1 using Kaisers criterion.

Sixty-two (62%) of the total variance is attributable to the

rst six factors; the remaining 22 factors together account

for only 38% of the variance as assessed by [68]. In other

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

words, 61.845% of the common variance shared by the 28

variables can be accounted for by the rst six factors, thus,

a model with six factors adequately represents all of the

factors.

Pallant [46] and Field [66] highlight that, once the numbers of factors have been determined, the next step is to

rotate and interpret the results. In this case, six components

were extracted and rotated. Varimax rotation was used,

which assumes that the factors are not related, and tends

to be easier and cleaner to interpret [46,63]. The rotation

does not aect the goodness of t of a factor solution.

Hence, the cumulative percentages of the six main components remain equal after rotation. However, the eigenvalue

and percentage of variance accounted for each factor does

change. The factor grouping based on Varimax rotation is

shown in Appendix 2. Each variable weighs heavily on only

one of the factors, while the loading on each factor exceeds

0.30. Below are the extracted principal factors and their

discussion.

17. Strategy focus

This principal factor accounts for 16.483% of the total

attractive variances and contains seven factors. The seven

factors constitute the programme strategy focus challenges

to the eective practice of programme management. The

factors are: lack of cross-functional working, lack of alignment of projects to strategy, lack of coordination between

projects, conicting project objectives, dening clear mission for the programme, lack of programme delivery infrastructure and lack of relevant training.

Li [68] discussed the higher and the lower loadings under

each principal factor of the components, to provide a deeper

insight; this research discusses the two higher and lower

loadings. Under strategy focus, higher loadings were made

by lack of cross-functional working and lack of alignment

of projects to strategy (Sig. = 0.740 and 0.729, respectively).

This indicates that lack of cross-functional working is the

most critical challenge in programme management strategy

focus component. However, it does not contradict the result

on the criticality of major challenges, but when rotated, it

appeared to have the highest loading. On both occasions,

the ranking of the factor remained high. According to Chittenden [73], there should be eective cross-functional working and alignment in order for the programme to succeed.

Hence, a lack of cross-functional working will constitute a

major challenge to the successful practice of programme

management in the construction industry.

The second highest loading factor under this component

is lack of alignment of projects to strategy (Sig. = 0.729); it

is not surprising that this factor ranks as the second major

challenge under strategy focus. OGC [74] indicates the

importance of integrating programme and project structures; hence, a lack of alignment of projects to strategy constitutes a major challenge, as no organisation can succeed

without fully bringing the projects of the programme

together in the planning of the expected benets. Blomquist

33

[69] states that all projects in a programme should be

aligned and consistent towards the objectives of the programme, failure to align them can cause diculty in realising the programmes benets.

The second lowest loading in this group is lack of programme delivery infrastructure (Sig. 0.578). This indicates

that if the programme has not set in place a delivery infrastructure (supply chain management, procurement systems,

communication systems, etc.), it will be dicult for the

stakeholders and programme team to interact and play

their part to ensure the successful delivery of the programme. Hence, the lack of a programme delivery infrastructure is a major challenge to the success of practicing

programme management. Subsequently, lack of relevant

training was the lowest factor (Sig. 0.424). Despite the

importance of continuous support and training in programme management, this factor emerged as the lowest

in this group. The factor ranked high in the criticality

assessment, but it loaded low under this principal factor.

The indication is that, to an experienced construction programme manager, training is essential, but on-the-job experience can replace any other form of training.

18. Human factor and communication

Principal factor 2 accounts for 10.130% of the total

attractive variance, and consists of ve human and communication factor challenges: a perception among the project

community that the programme will serve as an obstacle to

the timely accomplishment of project management, resistance to organisational change, people constraints, lack of

knowledge of portfolio management techniques and lack of

resources (human/nancial) to analyse project data. All of

these components are associated with the major human

and communication challenges to the successful implementation and practice of programme management.

Higher loadings are a perception among the project

community that the programme will serve as an obstacle

to the timely accomplishment of project management and

resistance to organisational change. The former is considered critical in the criticality ranking and regarded as one

of most critical factors for adopting and practicing programme management in the UK construction industry.

Lycett et al. [8] warned that some project management

organisations view programme management as additional

bureaucracy to curtail project mangers power to make

decisions and get on with their jobs. In the semi-structured

interviews, one of the programme managers in the public

sector observed that people resist changes for fear of losing their power and relevance in the organisation if new

systems are implemented.

The lower loadings are lack of knowledge of portfolio

management techniques (Sig. = 0.601) and lack of

resources (human/nancial) to analyse projects data

(Sig. = 0.471). Programmes entail managing a portfolio

of projects; where an organisation lacks the knowledge

regarding how to manage a group of projects, practicing

34

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

programme management will be dicult [30]. Hence,

organisations that do not have knowledge of managing a

portfolio of projects, may nd the implementation of programme management a huge challenge. In terms of lack of

resources (human/nancial) to analyse projects data,

according to Thomsen [42], programmes generate enormous data to communicate, absorb, document, integrate,

store and retrieve. It requires informing managers, enhancing collaboration, improving designs, defending claims and

reporting governance. On the other hand, it has also been

proven that programmes have the tendency to generate

huge amount of data [9] which require analysis to understand whether the programme has achieved its objectives

[27,70]. Based on the loading on this principal factor, a lack

of resources to analyse data is considered the lowest human

and communication factor. This position does not contradict the criticality ranking.

19. Financial factors

Principal factor 3 accounts for 10.012% of the total

attractive variance, and consists of four nancial aspect

challenges: initial funding and ongoing operational costs

to the organisation, lack of nancial skills of project/other

sta, nancial constraints, lack of clear company strategy

and lack of appropriate way to measure projects benets.

These factors are associated with the nancial constraints of programme management. Higher loadings are

initial funding and ongoing operational costs to the organisation (Sig. = 0.774) and lack of nancial skills of sta

(Sig. = 0.722). Initial funding and ongoing operational costs

to the organisation is regarded as one of most critical nancial factors for implementing and practicing programme

management in the UK construction industry. It has been

established that programmes are cost and capital intensive

[27,61], and therefore for organisations to commit

resources to programmes will certainly constitute a nancial challenge. This can explain why nancial constraints

and initial funding and ongoing operational cost top the list

under this principal factor.

Similarly, two lower loadings are lack of clear company

strategy (Sig. = 0.560) and lack of appropriate way to measure projects benets (Sig. = 0.342). Both challenges ranked

low in the criticality analysis and the components loading

in factor analysis. This implies that lack of appropriate

way to measure projects benets in programmes was the

lowest nancial challenge in the practice of construction

programme management. As a result, organisations may

have to devise an in-house method of assessing and measuring their programme benets.

from business leaders, late delivery of projects and lack of

cross-functional communication. These components are

associated with the leadership and commitment of major

challenges to the successful implementation and practice

of programme management.

Higher loadings are lack of knowledge to evaluate risks

(Sig. = 0.692) and frequent projects scope changes

(Sig. = 0.664) is regarded as one of most important factors

for adopting and practising programme management in the

UK construction industry. According to Kangari and Riggs [71], constructions projects consist of many risks, and

Williams and Parr [18] also conrm that programmes face

risk, but if properly identied and managed can translate

into opportunities. In addition, [42] highlights that, clients

transfer their risks to programme managers, and that if he/

she lacks the knowledge to identify, evaluate and manage

risks; the programme is likely to fail. Lack of knowledge

to identify, evaluate or manage risks can leave a programme vulnerable to failure. The two highest loading factors in this component ranked as highly critical major

challenges in the criticality ranking. According to [7], eective scope management is one of the key factors determining project success; whereas if the projects in a programme

are successful, they will, in turn, contribute to the success

of that programme. Therefore, a frequent scope change

constitutes a major challenge to a programmes success.

The two lower loadings are by late delivery of projects in

the programmes (Sig. = 0.556) and lack of cross-functional

communication (Sig. = 0.545). Abraham [23] states that,

the traditional approach to success in the construction

industry, places great emphasis on the ability to plan and

execute projects on time. The organisations that complete

projects in a timely manner within an established budget

and quality considerations are considered successful.

Therefore, if a programme delivers the functional projects

late, this results in a major challenge to the practice of programme management [3,18].

The second lower loading lack of cross-functional communication, contradicts the reality of successful programmes. Timely and eective communication between

teams and across the organisational boundaries is essential

to programme management success. Programme management survives on the exchange of timely and useful information between the stakeholders and programme team.

Lack of cross-functional communication is, therefore, a

major challenge to the practice of programme management

[6,27,69]. It is clear that lack of cross-functional communication can lead to the late delivery of a project, which will

in turn aect the timely delivery of a programme [70].

21. Strategy and awareness

20. Leadership and commitment

Principal factor 4 accounts for 8.926% of the total

attractive variance, and consists of ve leadership and commitment factor challenges: lack of knowledge to evaluate

risks, frequent projects scope changes, lack of commitment

Principal factor 5 accounts for 8.724% of the total

attractive variance, and consists of four programme understanding factor challenges: too many unrelated projects,

disappointment with nal programme benets, presenting a

detailed description of the intended roles of a PMO in the

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

organisation and lack of understanding of the value proposition that programme management provides.

Higher loadings are too many unrelated projects,

(Sig. = 0.752) and disappointment with nal programme

benets, 0.686. These major challenges too many unrelated

projects are considered as highly critical in the criticality

analysis, and this factor emerged strongly under strategy

and awareness. Programme management brings benets

through aligning, coordinating and executing multiple projects along the organisational objectives, more especially if

the organisation operates a myriad of small projects [2,72].

OGC [26] warned about lumping projects together in the

name of a programme. This research recommends that caution must be exercised in selecting the right projects, and

not bring projects that are not compatible to the programme [26]. Too many unrelated projects can be a major

challenge to construction programme management.

The lower loading is on lack of understanding of the

value proposition that programme management provides.

OGC [26] maintains that it is essential for an organisation

to set out the aim of operating programme management,

rather than doing it for the sake of fashion. Hence a lack

of clear value proposition is detrimental to the success of

any programme. One of the programme directors interviewed advised that organisations should be very clear

of what they want to achieve before implementing programme management. The values and benets expected

should be reected in the programmes business case [73].

22. Benets understanding

Principal factor 6 consists of two factors and accounts

for 7.570% of the total attractive variance: lack of understanding of the role of programme management in the organisation and lack of awareness of associated benets. These

factors are associated with the benets of understanding

programme management. There is a strong need for understanding what programme management stands for and

what it will contribute to the organisation [8,30,74]. In connection with the lack of understanding of the role of programme management in the organisation, an IT

programme managers who was interviewed, stated that:

Programme management is not an end in itself, but

rather a means to an end and is a means of delivering

long-term benets to the organisation that they could

not otherwise achieve. Therefore, where a company

determines that they lack long-term vision, programme

management cannot do anything for them. The start

point of a programme is where you want to get to. If

they get a long-term vision and they can see the means

within the context of their organisation for delivering

that, programme management would not ll that vacuum. If by any other means the company can deliver

their vision, then programme management is not for

them. If a company has a long-term vision but they do

35

not know how to deliver that long-term vision, then programme management would oer a solution to them.

On the benets of programme management, Reiss [61]

emphasised the importance of establishing ecient ways

to understand and measure the nancial and non-nancial

benets realised in programmes. The expected benets

should be carefully established and evaluated [70]. Organisations increasingly recognise that achievement of their

strategic objectives, including maintaining and improving

their competitive advantages, are dependent on both tangible and intangible assets [75]. Thus; a lack of awareness of

the associated benets is a major challenge to construction

programme management.

23. Successful implementation of programme management

In his work, [16] proposed a validated framework for

eective adoption and implementation of programme management into UK construction industry. The framework

consists of six trac colour coded progressive stages which

were developed based on the triangulation ndings from

literature review, questionnaire survey and semi-structured

interviews. The stages of the framework include: unawareness to awareness, understanding, programme planning,

piloting, implementation and customisation and

consolidation.

Associated with every stage of the framework are the

types of support required to overcome any challenges that

may be encountered in progression through the stages of

the framework as shown in Fig. 1.

The framework seeks to serve as an adaptable guide, it

should by no means be considered as the only means

through which organisations can be guided into the implementation and practice of programme management. In

Fig. 1. Framework for eective implementation of programme management [16].

36

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

addition to stages of the framework, on various occasions,

the participants of the semi-structured interviews all indicated that the implementation process should be in an evolutionary that will gradually become part of the system

and not in a big bang manner. Some of the recommendations are as follows:

Organisations that have been more successful in implementing programme management are those that implemented it in an evolutionary manner (Project

Manager, Construction).

Organisations should implement programme management in an evolutionary manner, realising benets at

each stage and do it against a structured maturity models; that denes what you need to do to achieve each

level of maturity (Programme Manager, Public Sector).

However, the literature also advised that organisations

should implement programme management in an evolutionary fashion:

Lycett et al. [8] assert that It is unrealistic to expect that

the programme approach can be introduced in a big

bang fashion due to the level of organisational change

mandated by its introduction. Consequently, it is more

fruitful to accept that organisational sophistication in

programme management will evolve and that it will

not be possible to apply some of the more advanced features of programme management unless appropriate

foundations exist.

The support required at the initial stage will predominantly be the combination of the support items listed above

from either the internal support system or external experts

in programme management [42].

24. Conclusion

Programme management, like any other management

approaches, faces challenges in the process of adoption,

implementation and practice. However, this research views

these challenges at two dierent levels. The rst level is at

the implementation stage, and the second level occurs after

the successful implementation and during the practice

stage. Challenges exist during the implementation stage:

the point when an organisation is in the process of transition from projectication to programmication. At this

stage, the most common challenges faced or anticipated

by the programme management organisations include: lack

of awareness, organisational, other challenges, and persuading directors to accept programme management as

the way forward.

The major challenges facing programme management

include: lack of commitment from business leaders (the

highest challenge in practicing programme management)

and presenting a detailed description of the intended role

of a programme management organisation (PMO) in the

organisation. However, the results provide a conicting

fact that, at the implementation stage, the major challenge

is lack of awareness, while at the practice stage, the challenge involves the lack of commitment from business leaders (directors). Whereas the directors buy-in does not

constitute any of the major challenges at the implementation stage. Regardless of the position, it is quite obvious

that a lack of awareness can constitute a problem with buying-in the directors and, in summary, directors cooperation is essential to the successful implementation and

practice of programme management.

With the data ranked, factor analysis was sorted to

reduce the major challenges to benet the planners and

implementers in categorising factors under certain components to eciently deliver them to programme managers

(or prospective programme managers). Factor analysis

was conducted, and the major challenges were reduced into

three factor using Scree plot and variables with eigenvalues

more than one. The factors were named as programme

control, human aspects, and political aspects. These factors

constitute the group of challenges that organisations may

face in practicing programme management.

Due to its complexity and the synergy of the functional

projects, programme management is an eective and proactive planning oriented discipline; in conclusion, high level

planning is required. This is essential to the successful

implementation and practice of programme management

in the UK construction industry. The organisations are

advised to cultivate planning and support their managers

to ensure the eective delivery of programmes. Training

can be provided in the form of CPD, workshops, or other

means of exchanging or fostering knowledge.

For the potential programme management organisations, it has been proposed that adequate caution should

be exercised in the process of implementation; a six-stage

approach has been proposed to progressively usher the

organisation into implementation and practice. The stages

include awareness, understanding, planning, piloting,

implementation and consolidation and customisation.

Appendix 1

Initial and rotated factor matrix of major challenges to practice of programme management.

Component

1

2

Initial eigenvalues

Rotation sums of squared loadings

Total

Variance (%)

Cumulative (%)

Total

Variance (%)

9.604

2.191

34.298

7.823

34.298

42.122

4.615

2.836

16.483

10.130

Cumulative (%)

16.483

26.613

(continued on next page)

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

37

Appendix 1 (continued)

Component

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Initial eigenvalues

Rotation sums of squared loadings

Total

Variance (%)

Cumulative (%)

Total

Variance (%)

Cumulative (%)

1.943

1.313

1.154

1.113

.995

.893

.809

.794

.688

.664

.643

.595

.540

.500

.485

.442

.381

.337

.330

.305

.291

.263

.242

.208

.145

.134

6.939

4.689

4.120

3.976

3.555

3.190

2.890

2.836

2.456

2.371

2.295

2.123

1.928

1.787

1.734

1.579

1.361

1.204

1.178

1.090

1.038

.938

.863

.742

.518

.478

49.061

53.750

57.870

61.845

65.400

68.590

71.480

74.316

76.772

79.144

81.439

83.562

85.490

87.277

89.011

90.590

91.951

93.155

94.332

95.422

96.461

97.398

98.261

99.004

99.522

100.000

2.803

2.499

2.443

2.119

10.012

8.926

8.724

7.570

36.625

45.551

54.276

61.845

Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

Appendix 2

Rotated factor matrix (loading) of major challenges.

Major challenges to the practice of programme management

Component

1

Strategic focus

Lack of cross-functional working

Lack of alignment of projects to strategy

Lack of coordination between projects

Conicting project objectives

Dening clear mission for the programme

Lack of programme delivery infrastructure

Lack of relevant training

Human and

communication

A perception among the project community that the programme will serve as an obstacle to

the timely accomplishment of project management

Resistance to organisational change

People constraints

Lack of knowledge of portfolio management techniques

Lack of resources (human/nancial) to analyse projects data

Financial factors

Initial funding and ongoing operational costs to the organisation

Lack of nancial skills of project/other sta

Financial constraints

Lack of clear company strategy

Lack of appropriate way to measure projects benets

Leadership and

commitment

Lack of knowledge to evaluate risks

Frequent projects scope changes

Lack of commitment from business leaders

Late delivery of projects

Lack of cross-functional communication

.740

.729

.719

.699

.627

.578

.424

.667

.648

.644

.601

.471

.774

.722

.698

.560

.342

.692

.664

.568

.556

.545

38

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

Appendix 2 (continued)

Major challenges to the practice of programme management

Component

1

Strategy and

awareness

Too many unrelated projects

Disappointment with nal programme benets

Presenting a detailed description of the intended roles of a PMO in the organisation

Lack of understanding of the value proposition that programme management provides

Benets

understanding

Lack of understanding of the role of programme management in the organisation

Lack of awareness of associated benets

.752

.686

.615

.411

.683

.513

Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Rotation converged in seven iterations.

References

[1] Rayner P. APM introduction to programme management. Association for Project Management; 2007.

[2] Ferns DC. Developments in programme management. Int J Proj

Manage 1991;9(3):14856.

[3] Milosevic DZ, Martinelli RJ, Waddell JM. Program management for

improved business results. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2007.

[4] Turner JR, Speiser A. Programme management and its information

systems requirements. Int J Proj Manage 1992;10(4):196206.

[5] Martinsuo M, Lehtonen P. Role of single-project management in

achieving portfolio management eciency. Int J Proj Manage

2007;25(1):5665.

[6] CCTA. Management of programme risk. HSMO; 1995.

[7] Burke R. Project management planning and control techniques.

Wiley; 2003.

[8] Lycett M, Rassau A, Danson J. Programme management: a critical

review. Int J Proj Manage 2004;22:28999.

[9] Reiss G. Programme management demystied: managing multiple

projects successfully. Spon Press; 2003.

[10] GAPPS. Dening programme types, <http://www.globalpmstandards.

org/program-manager-standards/general/dening-program-types/>;

2008 [accessed 09 October 2008].

[11] Pellegrinelli S, Partington D, Hemingway C, Mohdzain Z, Shah M.

The importance of context in programme management: an empirical

review of programme practices. Int J Proj Manage 2007;25(1):4155.

[12] Partington D, Pellegrenelli S, Young M. Attributes and levels of

programme management competence: an interpretive study. Int J Proj

Manage 2005;23:8795.

[13] Young NW. Key trends in the European and US construction

marketplace. SmartMarket report. Design and construction intelligence. Supported by CIOB, in Partnership with University of

Reading and CRC; 2008.

[14] DTI. The UK construction industry, <http://www.dti.org.uk/publications/construction_industry.pdf>; 2006 [accessed 20 November

2006].

[15] NAO. Modernising construction, <http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/00-01/000187es.pdf>; 2008 [accessed 20 June

2008].

[16] Shehu Z. The framework for eective adoption and implementation

of programme management in the UK construction industry. In:

Built and natural environment. PhD thesis. Glasgow Caledonian

University: Glasgow; 2008.

[17] Martin P, Nicholls J. Creating a committed workforce. IPM

Publication; 1987.

[18] Williams D, Parr T. Enterprise programme management: delivering

value. Pelgrave MacMillan; 2006.

[19] Black C, Akintola A, Fitzgerald E. An analysis of success factors and

benets of partnering in construction. Int J Proj Manage

2000;18(6):42334.

[20] Sambasivan M, Yun Fei N. Evaluation of critical success factors

of implementation of ISO 14001 using analytic hierarchy

process (AHP): a case study from Malaysia. J Cleaner Prod

2007;16:142433.

[21] Fowler A, Walsh M. Conicting perceptions of success in an

information systems project. Int J Proj Manage 1999;17(1):110.

[22] Cash C, Fox R. Elements of successful project management. J Syst

Manage 1992;43(9):102.

[23] Abraham G. Critical success factors for the construction industry. In:

Proc, construction research congress in construction wind of change:

integration and innovation (CD-ROM). Construction Institute,

Construction Research Council, ASCE, University of Colorado at

Boulder; 2003.

[24] Choi B, Poon SK, Davis JG. Eects of knowledge management

strategy on organizational performance: a complementarity theorybased approach. Int J Manage Sci 2007;36:23551.

[25] Olomolaiye A. The impact of human resource management on

knowledge management for performance improvements in construction organisations. In: Built and natural environment. PhD thesis.

Glasgow Caledonian University; 2007.

[26] OGC. Programme and project management and careers, <http://

www.ogc.gov.uk/programme_and_project_management_and_careers.asp>; 2007 [accessed 04 June 2007].

[27] Bartlett J. Managing programmes of business change. 1st ed. Project

Manager Today; 2002.

[28] OGC. Managing successful programmes. TSO; 2003.

[29] Thiry M. For DAD: a programme management life-cycle process. Int

J Proj Manage 2004;22(3):24552.

[30] Reiss G, Anthony M, Chapman J, Leigh G, Payne A, Rayner P.

Gower handbook of programme management. Gower Publications;

2006.

[31] Denscombe M. The good research guide for small-scale social

research projects. Open University Press; 2007.

[32] Fellows R, Liu A. Research methods for construction. Blackwell

Science; 1997.

[33] Bryman A, Bell E. Business research methods. University of Oxford

Press; 2003.

[34] Pathirage CP, Amaratunga RDG, Haigh RP. The role of philosophical context in the development of theory: towards methodological

pluralism. Built Hum Environ Rev 2008;1(1):110.

[35] Wisker G. The postgraduate research handbook. 2nd ed. Palgrave

Publication; 2008.

[36] Webb EJ, Campbell DT, Schwartz RD, Sechrest L. Unbstrusive

measures: nonreactive measure in social sciences Chicago. Rand

McNally; 1966.

[37] Palmquist M. Content analysis, <http://www.colostate.edu/

Depts/WritingCenter/references/research/content/page2.htm>; 2001

[accessed 29 January 2008].

[38] Busch C, De Maret PS, Flynn T, Kellum R, Le S, Meyers B, Saunders

M, White R, Palmquist M. Content analysis. Writing@CSU.

Z. Shehu, A. Akintoye / International Journal of Project Management 28 (2010) 2639

[39]

[40]

[41]

[42]

[43]

[44]

[45]

[46]

[47]

[48]

[49]

[50]

[51]

[52]

[53]

[54]

Colorado State University Department of English, <http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/research/content/>; 2005 [accessed 29 January

2008].

Fernie S, Green SD, Weller SJ, Newcombe R. Knowledge sharing:

context, confusion and controversy. Int J Proj Manage

2003;21(3):17787.

Egan J. Rethinking construction: the report of the construction task

force. HMSO; 1998.

Dainty A. A call for methodological pluralism in built environment

research. In: PRoBE conference. Glasgow Caledonian University,

Scotland, UK; 2007.

Thomsen C. Program management: concepts and strategies for

managing capital building programs. Construction Management

Association of America Foundation; 2008.

Adamson DM, Pollington AH. Change in the construction industry:

an account of the UK construction industry reform movement 1993

2003. Routledge Publishing; 2006.

Morton R. Construction UK: introduction to the industry. Blackwell

Publications; 2002.

Yang J, Peng S. Development of a customer satisfaction evaluation

model for construction project management. Build Environ

2008;43(4):45868.

Pallant J. SPSS survival manual. John Wiley Publications; 2001.

Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;

1978.

Abdul Kadir MR, Lee WP, Jaafar MS, Sapuan SM, Ali AAA.

Factors aecting construction labour productivity for the Malaysian

construction projects. Struct Surv 2005;23(1):4254.

Kometa ST, Olomolaiye PO, Harris FC. Attributes of UK construction clients inuencing project consultants performance. Constr

Manage Econom 1994;12:43343.

Odeh AM, Bettaineh HT. Causes of construction delay: traditional

contracts. Int J Proj Manage 2002;20(1):6773.

Chan WM, Kumaraswamy MM. A comparative study of causes of

time overruns in Hong Kong construction projects. Int J Proj Manage

1997;15(1):5563.

Cheng J. Discussion of importance index in technology foresight.

National Centre for Science and Technology for Development Ministry

of Science and Technology of the People Republic of China; 2002.

Kamin PF, Holt GD, Kometa ST, Olomolaiye PO. Severity diagnosis

of productivity problems a reliability analysis. Int J Proj Manage

1998;6(6):107113.

Ogunlana S, Siddiqui Z, Yisa S, Olomolaiye PO. Factors and

procedures used in matching project managers to construction

projects in Bangkok. Int J Proj Manage 2002;20(5):385400.

39

[55] Thite M. Leadership styles in information technology projects. Int J

Proj Manage 2000;18(4):23541.

[56] Raz T, Michael E. Use and benets of tools for risk management. Int

J Proj Manage 2001;19(1):917.

[57] Akintoye A, MacLeod MJ. Risk analysis and management in

construction. Int J Proj Manage 1997;15(1):318.

[58] Gardner PL. Scales and statistics. Rev Educ Res 1975;45:4357.

[59] Sapsford R, Jupp V. Data collection and analysis. The Open

University Press; 1996.

[60] Papastathopoulou PG, Gounaris SP, Avlonitis GJ. Successful to newto-the-market versus me-too retail nancial services. Int J Bank Mark

2006;24(1):5370.

[61] Reiss G. Benets management a paper for congress, http://www.

e-programme/uploads/articles; 2000 [accessed 30 June 2008].

[62] Kaiser HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometika

1974;39:316.