North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil Fields

Diunggah oleh

billcaraherJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil Fields

Diunggah oleh

billcaraherHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in the Bakken Oil Fields

William R. Caraher

Bret Weber

Kostis Kourelis

Richard Rothaus

ABSTRACT

Over the past three years, the North Dakota Man Camp Project has documented the

archaeology of home in over 50 contemporary, short-term, workforce housing sites in the

Bakken oil patch in western North Dakota. This article integrates recent scholarship in

global urbanism, archaeology of the contemporary past, and domesticity to argue that the

expansion of temporary workforce housing in the Bakken reflects a global periphery that

lacks infrastructure or capital to rapidly respond to the pressures of an increasingly fluid

movement of global capital and labor. The position of the Bakken produced short-term

housing strategies that embrace both traditions of American domesticity and global trends in

informal urbanism. A series of practical acts of architectural intervention straddle the line

between the ideals of fixity characteristic of the American suburb and the mobility of RVs.

The archaeological and architectural analysis of the Bakken man camps documents new

forms of informal housing and offer a glimpse of the city-yet-to-come.

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Introduction

The New York Times selected the word "man camp" as one of the most important

words of the year at the end of 2012 (Barrett 2012). Referring to the temporary housing

facilities for oil workers in North Dakota, the choice illustrates the impact that the Bakken

oil boom has made on the American national consciousness. The fascination with North

Dakotas man camps extends into the visual media including images of this new housing

form proliferating in the press (Gorney 2014; Brown 2013; Taylor 2013). Man camps have

provided a lexical and visual testament to an otherwise invisible subterranean process of

hydraulic fracking. Typically taken from a distant vantage point or focusing on human

subjects, the images of North Dakota's man camps resonate with other impermanent

housing forms such as refugee camps, natural disaster camps, and labor camps. Whether in

Greece, New Orleans, Dubai, or North Dakota, camps serve as home to an increasing

number of people, making them a permanent form of dwelling for an increasingly significant

section of the human population. The phenomenon has prompted Alex Hailey to argue that

camps are already the 21st centurys dominant form of dwelling (Hailey 2009).

In spite of the local, national, and international attention to the man camp

phenomenon in North Dakota, there are limited academic studies of the material,

architectural, and anthropological makeup of these sites. This article introduces the work of

the North Dakota Man Camp Project (NDMCP). The NDMCP is an ongoing project that

uses archaeological methods to document current workforce housing practices in the Bakken

oil patch of western North Dakota (Fig. 1). Our work situates the temporary housing in the

Bakken at the intersection of two key issues for understanding workforce housing in a

historical and contemporary context. First, the location of the Bakken at a global and local

periphery creates a space for practices associated with the informal urbanism that thrives

outside of institutions designed to support regular and controlled development. Second, the

peripheral location of the Bakken provides valuable architectural and archaeological

evidencedistinctly local manifestations of global transformationsand opportunities for

understanding negotiated domesticity in postindustrial America. The documentation

conducted by the NDMCP addresses the gap in the archival record and provides critical

analysis of these phenomena.

Man camps are an ad hoc solution to a housing crisis and represent reluctance shown

by local inhabitants and the oil industry to build residential infrastructure for the men and

few women who have traveled to North Dakota to work in the oil boom. The most recent

Bakken oil boom started with the introduction of hydraulic fracturing technologies (fracking)

to the long-standing Bakken oil field in 2008. By the spring of 2012, North Dakota

surpassed Alaskas oil production to become the second busiest oil producing state in the

United States. To extract oil from the thin layers of shale, the state welcomed a short-term

influx of workers, which reversed the regions long-term population decline (Robinson 1966;

Porter 2009). High oil prices, improved technologies, and optimistic assessments of the

Bakken reserves created an economic and demographic boom in Williams and McKenzie

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Counties that many predicted would last 30 years or longer. One of the major consequences

of this boom has been a severe housing shortage throughout the state (North Dakota

Petroleum Council 2011). The North Dakota Department of Commerce estimated in the fall

of 2012 that available beds for new workers numbered just over 15,000, while a trade

magazine suggested a higher figure of 21,511 planned or available beds to accommodate the

estimated 65,000 new jobs. If growth continues, some have projected a state population of

one million by 2020, which is an increase of over 30% in a dozen years (Dalrymple 2012; for

others see Bangsund et al. 2012; Hodur et al. 2013). Many of these jobs, however, relate to

the first phase of oil extraction and involve the labor-intensive processes of drilling, fracking,

and building the oil and gas infrastructure. The short term employment and surge in

production created the need for temporary housing that is unlikely to persist into the future.

The NDMCP project studied over 50 camps in the Bakken oil patch (Fig. 2). These

camps ranged in size from a few beds to crew camps large enough to be counted among the

states 20 largest cities. The methods employed in documenting the Bakken work camps

involved systematic photography, architectural drawings, textual description, oral interviews,

and aerial mapping. Acknowledging the eventual disappearance of the settlements, the

NDMCP seeks to create a permanent record of the settlements, and a benchmark for future

archaeological explorations that might reveal the process of their disintegration.

One of the fundamental conclusions of the project was that man camps are not a

unitary phenomenon but can be broken down into three categories from the most

centralized and formal to the most haphazard and informal, as Types 1, 2, and 3. Type 1

camps are distinguished by prefabricated buildings imported on an industrial scale and

frequently operated by specialized companies from outside the region (Fig. 3). The cost of

staying in a camp of this type is often part of an employees overall contract with a large,

multinational corporation operating in the oil patch. Many are constructed and managed by

multinational logistics companies, like Target Logistics, specializing in housing for workers

in extractive industries on a global scale. In general, the appearance of the more formal

camps is characterized by uniformity to the point of military-like precision.

Type 2 camps resemble trailer parks (Fig. 4). They show much greater diversity in lay

out and in the variety of individual units, consisting primarily of RVs and mobile homes

ranging from third wheel type campers to large motor coaches. They generally include

leveled gravel pads for each unit, wide roads for access, hookups for electricity, and, in most

cases, connections for water and sewage utilities. This type of camp is the most common,

although accurate numbers of camps, lots, and residents remain elusive. In general, the

occupants of Type 2 camps rent the lot and pay for utilities, but provide their own RV,

although some camps offer RVs for rent and companies do sometimes provide RVs for their

crews. In general, rents are relative to location and services, and range from $600 to $1,200

per month for those who own their RVs, and up to $2,000 for those renting both space and

trailer. Most camps include some form of administration that collects rents, offers limited

amenities, and maintains the roadways. Many of these camps are financed by non-local

capital and function with minimal oversight from local municipalities or, more frequently,

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

county governments. To residents, however, many of these informal camps appeared at a

time when people just kind of swarmed . . . and waited for someone to come around and

kick them off or rent the place (Personal Interview, Craig Hooper, August, 2012).

Type 3 camps lack fixed infrastructure and are generally comprised of haphazardly

congregated RVs (Fig. 5). Many are illegal, squatting on available ground, and operate

outside administrative oversight. Typically small with only a handful of campers, Type 3

camps are the most difficult to sustain. Without water, electricity, or sewage they are

particularly difficult to maintain through the cold winters. Some of the earliest informal

camps were almost certainly squatter settlements that violated local laws. Based on press

accounts, Type 3 camps were once a common feature in the Bakken and included the

famous camp in the Wal-Mart parking lot, but since 2012 most squatter camps have largely

been eliminated.

The NDMCP has documented all three types of man camps, but focuses on the

most common Type 2 facilities as they tend to offer the most revealing articulation of new

social and architectural forms. Type 1 camps are so rigorously controlled by central

authorities that they offer little architectural variation. Type 3 camps, on the other hand, are

so impermanent that they rarely afford the formation of a spatial identity and remained

relatively elusive to our research program.

This article is divided into two sections. The first takes a theoretical approach in an

attempt to situate the material evidence within the context of global peripheries, informal

urbanism, and the archaeologies of the contemporary past. The second section investigates

the negotiated domesticity expressed in the architectural manipulations of interior and

exterior space within Type 2 man camps.

Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past, Informal Urbanism, and Global

Periphery

Our approach to documenting workforce housing drew on recent directions in

archaeology and architectural history. First, our work is informed by the archaeology of the

contemporary past, which has been particularly productive in its focus on sites of short-term

or ephemeral occupation. Larry Zimmermans archaeology of homelessness, the archaeology

of contemporary protest sites, photographic documentation of graffiti, and the archaeology

of tourism collectively demonstrate how archaeological approaches to sites of contemporary

contingency have the potential to inform issues of immediate social and political concern

(Kiddley and Schofield 2010, 2014; Zimmerman 2010; Schofield and Anderton 2000; Myers

2010; Graves-Brown and Schofield 2011; ODonovan and Carroll 2011). By documenting

the recent past through its material culture, archaeologists have demonstrated that the

material world represents and reinforces agency and the dynamic processes that bring issues

of social and economic justice to the material culture of labor, leisure, and everyday life. The

archaeological study of spaces and objects has the potential to give voice to marginal

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

communities in ways that traditional historical studies grounded in the more restrictive

practices associated with textual evidence tend to overlook.

This interest in archaeology of the contemporary world complements long-standing

interests by historical archaeologists on factory sites, working and middle-class housing, and

extractive industries. Archaeologists have documented mining camps through time and

developed a substantial body of scholarship related to the archaeology of labor and working

class life. Bernard Knapps work on the remains of mining settlements and extractive

landscapes dating to the Bronze Age on the island of Cyprus demonstrated the longstanding

correlation between temporary settlement and mining (Knapp 1998; 2003). Scholars of

Australia and South America have likewise studied the role of workforce housing in the

colonial transformation of extractive industries on those continents in the 19th and 20th

centuries (e.g. Garner 2012; Van Buren and Weaver 2012). For the U.S., a recent volume of

Historical Archaeology dedicated to life in western work camps located the archaeology of

workforce housing in the context of the American west (Van Bueren 2002). For the

American West, scholars like David Hardesty have pioneered the documentation of the

often-times ephemeral and overlooked landscape of resource extraction (Hardesty 1988;

2002). Susan Lawrences work on gender and domesticity in the temporary camps of the

Australian goldfield reinforced the key role of women and gender in understanding domestic

spaces associated with extractive industries (Lawrence 1998; 1999). Paul Shackels recent

survey of the archaeology of labor and working-class life emphasized how this scholarship

understood archaeological remains as evidence for agency, control, and resistance in working

class housing and the life of working class families (Shackel 2009).

Echoing the work of geographers, theorists, and archaeologists, architectural

historians have come to see camps and temporary housing as a quintessential architecture of

modernity (Jackson 1960; Drury 1972; Jackson 1984; Thornburg 1991; Wallis 1991; White

2000; Hart, Rhodes, and Morgan 2002; Hailey 2008; Van Slyck 2010). In the 20th and 21st

centuries, camps have adapted to such diverse functions as military occupation, refugee

settlement, recreation, and protest sites. The work of Charles Hailey provides a link to

urbanism which forms a crucial interpretative lens for this article. He suggests that

impermanent housing (shanty towns, favelas, encampments, colonias, etc.) has become the

architectural staple for more than work camps, factory labor, and rural industry, and has

become a key component of informal urbanism in the 21st century (Hailey 2009). The

informal housing sites surrounding many of the cities yet to come (Dakar, Pretoria,

Douala, Jeddah, or Buenos Aires) have more in common with the man camps of the rural

North Dakota than the cites of the past (Simone 2004; Perlman 2010). Their rapid growth,

contingent character, and lack of institutional control have created highly visible

opportunities for architectural agency in creating spaces that leave little evidence in textual

sources.

Our study of contingent workforce housing has been specifically influenced by

recent work on informal urbanism in the U.S. and throughout the global periphery. The

relative wealth and economic opportunity in North Dakota tends to place it outside the

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

discourse of a global periphery that centers on the developing world (e.g. Chase-Dunn,

Kawano, Brewer 2000). The rapid workforce expansion represented a challenge for planning

and investment by the state of North Dakota, local municipalities, and by corporate interests.

Consequently, housing in North Dakota developed in an ad hoc way. The oil industry

provides housing for only a small fraction of the most professionalized workforce, usually in

Type 1 camps provided by global logistics companies (Rothaus 2014). Many newcomers to

the Bakken, however, work in industries either directly or indirectly related to oil extraction

such as pipeline work, truck repair, food and hospitality service, and general construction.

For these residents, outside investors funded the construction of temporary and informal

RV and mobile home parks, which are primarily Type 2 camps. The rapid pace of workforce

expansion and the struggle of communities in western North Dakota suggest a peripheral

character, but this should not imply that the communities and residents of the region lack

agency or are powerless against the depredations of an increasingly de-centered core.

Instead, certain economic, political, and broadly structural limitations common in both

North Dakota and the global periphery shape local practices.

The development of man camps took place in the periphery of the small cities and

towns that offer permanent housing. Most workforce housing in the Bakken stands outside

the towns of Tioga, Williston, Watford City, and more recently Dickinson (Fig. 6). In this

respect, the Bakken follows patterns evident in the developing world, where cities are ringed

by informal working-class settlements. Similar to the informal settlements that surround Rio

de Janeiro and other cities of the global south, the man camps of North Dakota stand

outside the gaze, jurisdiction, and living space of the established economic and political

order (Perlman 2010). This not entirely dissimilar to American suburbs that tend to ring

cities with a relatively stable affluence but represent a varying degrees of integration with the

urban core (Duncan and Duncan 2004). Whereas suburbs have asserted their own

independence from traditional city center for a wide range of economic, political, and social

reasons, the lack of local jurisdiction over peripheral man camps is not accidental: many local

communities passed explicit ordinances to prevent or restrict the development of man

camps within city limits. In this way, the Bakken settlement patterns paralleled the

establishment of colonias on the U.S.-Mexico border that emerged at the fringes of urban

areas providing access to employment without limits imposed by vigilant municipal

governments (Ward 1999). Similarly, while the oil boom provides affluence to some local

residents, the migrant labor required for this affluence is kept at arms-length from the small

urban core.

Pushed outside city limits, man camps stand at the margins of municipal building

codes, zoning ordinances, as well as human services centered in the cities. While established

North Dakota communities are beginning to catch up with population pressures, their slow

response during the first years of the oil boom allowed for an informal urbanism to thrive at

the edge of these towns. In this context, standardization in practice and appearance is much

more likely to derive from local rules, practical realities, and informal consensus among

residents, as from municipal or other government authorities.

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Negotiating Domesticity in Temporary Settlement in the Bakken

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the need for labor housing was met by company

towns or by private developers engaged in housing speculation (Wright 1981), with informal

developments like labor camps typically emerging along the edges of towns. Since the 1950s,

informal or self-help housing was the dominant domestic form in the developing world,

where it confronted the infrastructural deficits of the state and the economy (Ward 1982: 113). But Americas postwar economic boom had been so integrally tied to the housing sector

that informal urbanism, in the form of trailer parks and other impermanent housing,

represented only a fraction of the domestic stock.

In the 21st century, urban planners note that informality has come to influence many

manifestations of urbanism in the U.S.:

Partly a result of globalization, deregulation, and increasing immigrant flows,

partly as a response to economic instability and increasing unemployment

and underemployment, and partly because of the inadequacy of existing

regulations to address the complexity and heterogeneity of contemporary

multicultural living, informal activities have proliferated in U.S. cities and are

clearly reflected in the built environment (Mukhija and Loukaitou-Sideris

2014:1).

North Dakotans embraced this informality as a way to avoid repeating the perceived

mistakes of the early 1980s, when the oil bust and rapid exodus of workers left a real estate

crisis in its wake. Taxpayers stuck with the municipal debt that had financed the building of

necessary trunk infrastructure (roads, sewer lines, etc.) were hesitant to invest in housing for

the oil boom of the 2010s. Instead, responses to housing demands echoed the global trends

and left the problem of housing the rapid influx of workers to outside forces. At first, there

was a boom in ad hoc Type 3 camps, but these were generally cleared away or replaced by

2012. As the situation became slightly more formalized, many medium sized and large,

centralized, Type 1 man camps became increasingly visible along the main thoroughfares.

But, it was the informal Type 2 camps that came to provide the majority of temporary

workforce housing in the Bakken.

The impermanence of historic, contingent settlements like those found in the

Bakken contrast sharply with the traditional views of middle-class home ownership and

domestic life that emphasize stability and long-term fixity in the landscape (Jackson 1953;

Jackson 1984; Duncan and Duncan 2004). This illusion of suburban permanence emerged

from the rural ideal that served to market the American suburbs to a middle and upper class,

urban population from the late-19th and mid-20th centuries (Duncan and Duncan 2004). In

the Bakken, architectural permanence and attachment to the land has been deployed as an

exclusionary technique designed to distinguish the nomadic newcomers from those living in

the small communities before the boom. At the same time, the historical need for affordable,

mobile housing in the American west underscores the largely ideological tension between

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

long-term and temporary housing (Jackson 1960; AUDC, Sumrell, and Varnelis 2007).

Nowhere was the tension between permanence and mobility more apparent than in the use

of RVs for the recreational retreats of the mid-20th century middle class (Hailey 2008). The

freedom of the road offered by RVs complemented the fixity of the suburban home and

defined life in the RV as a temporary escape from middle-class domesticity. Permanent and

temporary were interdependent. Although more economical than the cost of motels, the RV

required financial resources for its acquisition, maintenance, and operation during holiday

vacations. The transience that it afforded for the average two-week duration of its use was

indirectly supported by the owners access to domestic real estate to park the large vehicle

for the remaining 50 weeks of the year. On the fringes of the recreational ideal, however,

mobile homes served as permanent housing solutions for a growing population of internal

migrants or impoverished natives. According to the 1990 census, 7% of the American

population lived in a mobile home (Hart et al. 2002:2). Derogatory epithets, like trailer

trash, emphasize a compromised domesticity associated with long-term residence in fixed

mobile homes or RVs.

However, recent work on short-term and informal urbanism demonstrates that life

in work camps, colonias, and trailer parks offers opportunities for architectural agency. This

was reinforced by camps in the Bakken. Displacing broadly accepted expressions of

domestic values, the residents of mass-produced mobile homes and RVs modified and

improved their homes to meet the practical realities of challenging climates. The

manipulation of RVs in North Dakota resembles the bottom-up adaptation evident in other

contexts, such as the manipulation of gun trucks by American soldiers in the warzones of

Vietnam and Iraq (Kollars 2014) or the DIY interventions of consumer products, as in the

case of IKEA hackers (Rosner and Bean 2009). This exercise of architectural agency speaks

both to the distinct character of work in the Bakken oil patch as well as the negotiation of

domestic space in the 21st century.

Unlike permanent homes, RVs provide few opportunities for manipulation beyond

built-in flexible features like slide-outs and awnings. Assuming the RV design process is

complete, architectural historians have completed only limited documentation of

architectural agency among users. Notable exceptions include Kingston Heaths (2007)

regional comparisons, noting that in Montana occupants build enclosed wooden mudrooms,

while in North Carolina they construct covered porches. Heath characterizes this process as

cultural weathering. Peter Wards studies of spatial extensions in the trailer settlements

associated with colonias in Texas along the U.S.-Mexico border (Ward 1999; 2014:70) argue

that manipulations and additions demonstrate the creativity and self-management of

otherwise marginalized and disenfranchised populations. These innovations stem from the

structural limitations of the RV, the social networks present in workforce housing

communities, and the absence of strong institutional barriers.

Five key aspects of informal workforce housing in the Bakken help to illustrate ways

that residents negotiate domesticity and architectural agency through social practice. These

include insulation practices, enclosures, platforms, property demarcations, and ritual objects.

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

These aspects of life in workforce housing speak directly to the tension between the need for

mobility in short-term housing and traditions of fixity central to American traditions of

suburban life.

Insulation. One of the most fascinating aspects of architectural agency emerges in

the process of de-mobilizing RVs: the practice of insulating an RV for the cold North

Dakota winter provides a poignant illustration of both the architectural transformation from

mobile to stationary structures as well as the social relationships that facilitate the

dissemination of related techniques (Fig. 7). RVs are designed to be occupied for an average

of two weeks (the average American workers allotted vacation), during the temperate

months of late spring, summer, or early fall. To survive a North Dakota winter, the owners

of the RV must modify the vehicles skin to increase the total R-value of thermal resistance.

The RV is understood as a unitary envelope with weak zones through which air and

heat leaks. Residents employ a range of strategies to maintain functionality and to make an

RV comfortable when temperatures dip below freezing for weeks on endsometimes with

sustained temperatures well below zero degrees Fahrenheit. For example, several companies

advertise on-site insulation service including installation of thick vinyl skirting around the RV

base. Many residents, however, see these services as overpriced and ineffective, and insulate

their units according to various techniques learned through conversations with coworkers

and camp neighbors. Much is also learned through trial and error.

The most common technique is to apply extruded polystyrene foam insulation to the

most vulnerable areas and especially the locus of mobility, the wheels. Some residents utilize

wood frames (Fig. 8). Remaining gaps are then sealed with spray foam insulation. While

various types of insulation are available at stores in Williston and Dickinson, many residents

travel to Minot to avoid higher prices in the oil patch. Extruded polystyrene costs around

$30 a sheet, and most large RVs require eight to ten sheets for full coverage. The expense

and suspicion of price-gouging result in some insulating with hay bales, rolled fiberglass

insulation, and plywood alone.

Other crucial areas for insulation are windows and slide-outs (extensions designed

expand interior space). The weak seals around these slide-outs and the thinner aluminum

skin in these areas allow cold air to leak inside. Windows can be sealed from either the

outside or the inside often using reflective insulation attached directly to the RV window

frames. Like the wheels, once covered, the slide-outs can no longer fulfill their service to

mobility. Polystyrene blue is ubiquitous throughout the man camps, creating a surreal

relationship between the vertically weatherizing plastic and the horizontally expansive blue

sky above. In the summer months, stacks of plywood-backed polystyrene are visible beneath

the RVs as comfort in the summer heat is enhanced by the flow of air.

Water and sewage hook-ups demand particular attention in the winter. Occupants

typically enclose the water and sewage pipes in fiberglass insulation and electrical heat-tape

to prevent freezing. Some go further and build small, insulated boxes to provide additional

insulation. To guard against frozen pipes, some camp managers perform regular inspections

as problematic units can imperil the entire park. But even with proper diligence, frozen pipes

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

remain a constant problem. One major camp lost water and sewage for close to two months

during the winter months demonstrating how fragile basic comforts can be in these shortterm settlements.

By covering the wheel zone, extended slide-outs, and water and sewage hook-ups

with insulation, the RV bricoleur resists the cold of winter but also expresses the vehicles

fixity and long-term stability. The RV becomes immobilized as its wheels are encased within

an adhered rectilinear frame. The insulated tether of the sewage and water pipes tie the RV

to its lot, and the extended slide-outs, covered with insulation, further emphasize the

anchored condition. This transformation of the mobile RV to a more permanent residential

unit develops through informal knowledge networks with minimal involvement of either

prefabricated components or formal institutional authority.

Enclosure. Like insulation practices, informal workforce housing sites also

demonstrate opportunities to adapt the physical space of an RV through various methods of

architectural enclosure. The construction of enclosures represents a key strategic adaptation

to life in an RV park, as well as an opportunity to demonstrate skills in building and

individual creativity. The hodgepodge of different sizes and styles of enclosures contribute

to an irregular and informal appearance across the camp, and have led them to be a target of

increased regulation particularly in large and highly visible camps. Williston Foxrun, a camp

with over 300 lots for RVs, at one point featured over 200 enclosed additions, and while the

number of enclosures is exceptional, the percentage of units with enclosures reflected the

general ubiquity of these features across the Bakken.

Most enclosures involve the use of plywood to expand the livable area of the RV. In

some cases, residents create a small room adjacent to the RVs entrance typically called a

mudroom or entrance (Fig. 9). Like extruded polystyrene used for insulation, the

plywood sometimes comes from a lumberyard or big-box home improvement center, and is

loaded on a pickup truck and brought to the camp. In other cases, however, residents

construct their mudrooms using scrap wood left behind or modify completed enclosures

abandoned by previous residents at departure. Some of the larger camps set aside areas for

provisional discard of scrap lumber. In other cases, whole mudrooms are offered for sale.

Repurposed mudrooms are not uncommon and are easily recognizable when their shed roof

is higher than the roof of an RV indicating that the enclosure is in secondary use. Many of

the oil field workers were trained in the building industry, and show great facility in creating

and adapting these additional spaces.

The function of the mudroom or entrance vestibule includes creation of a space

where a resident can remove soiled work clothes, muddy boots, or the layers of clothing

required for outdoor work in the North Dakota winter. With one door leading inside the RV

and a second leading to the camp outside, mudrooms create both a layer of security and an

additional volume of air that can function as a layer of insulation. In a few of the larger RV

parks the construction of mudrooms took on a competitive flare with residents attempting

to build more elaborate and expansive mudrooms than their neighbors, including examples

of large mudrooms being insulated thoroughly and offering additional living and sleeping

10

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

space. Some of these additions extend the entire length of the RV and the largest completely

enclose the RV in an insulated wood structure.

The mudroom addition transforms the space of the RV in more than merely

practical ways. By attaching a mudroom perpendicularly and at one end of the long vehicle

wall, the enclosure turns the rectangular shape of the RV into an L shape. Framed by the

parallel side of the neighboring RV, the mudroom not only increases the dwellings much

interior space, but also reinforces the formal stability of the new home, and anchors the RV

in a manner that visibly denies the implied aerodynamic motion and even its intended

directionality. The added vestibule also introduces a historical layer of formality and privacy

in an undifferentiated interior space of the RV, where kitchen, bedroom, and living room are

one, and subtly refers to the specialization of rooms of a Victorian home (Wright 1981:111).

The perpendicular mudroom likewise shifts the axis of entrance. Unsurprisingly, people take

great pride in their customization projects. Describing a particularly elaborate extension that

created a living room complete with large screen TV outside of the body of the RV, one

resident exclaimed, its very niceits almost like home! (Personal Interview, Lisa Holman,

August, 2013). The addition of enclosed space not only increases the fixity of the RV but

also creates the kind of meaningful spatial individuation associated with traditional

domesticity.

The threshold of the door has also become a contested site of architectural agency.

While residents of RV parks continue to experiment with mudrooms and other architectural

modifications, management in the parks and even municipal governments have tried to limit

the size and function of these additions. The check on the rampant individualization at longterm RV parks is increasingly restricted by seemingly ad hoc applications of state and local

laws, and similarly situational policies enforced by camp owners that dictate the extent to

which space can be modified. For example, counties are drafting ordinances to limit the

extent to which units may be enclosed in freestanding architecture (Personal Interview,

Denise Sasser, Williams County Planning, Zoning, and Building Department, July, 2014).

The reasons behind these laws are explicitly about safetyprimarily fire concernsbut also

have as much to do with the aesthetics of temporary housing within city limits. The

permanence of the elaborate architectural enclosures, their provisional style, and their

sometimes shoddy construction techniques run counter to an aesthetic of permanence,

substance, and consistency traditionally privileged by suburban development (Duncan and

Duncan 2004). Recently, Williston Foxrun embarked on a campaign to eliminate some of

the larger additions. Over 70% of the units in the camp had some form of mudroom and a

substantial minority of those were large and elaborate. During a visit in September 2014,

several partially dismantled additions stood in otherwise vacated lots, providing a ghostly

illustration of the transitory nature of boom economy workforces. The architectural

elaboration of RVs and mobile homes represents a key strategy in consolidating informal

settlements and can mark a step toward permanent and more formal settlement.

Platforms and Paths. Another common architectural intervention involves exterior

platforms adjacent to the threshold of the necessarily elevated RV and mobile home doors

11

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

(Fig. 10). Such platforms run parallel to the course of the trailer and often provide an

elevated path between the units door and an area set aside for a vehicle. Most are made of

salvaged materials with shipping pallets being by far the most common. Pallets often serve as

the foundation for decks made of plywood or other scrap lumber available around informal

workforce housing sites. One innovative, and perhaps ironic, RV resident used a group of

old solar panels as an elevated walkway from his door to his truck.

Platforms and paths provide elevated surfaces to address snow and ice during winter

and mud and puddles during spring. Snow shovels are frequently left at the ready by the

door of a mudroom or RV during the winter months. Thaws often cover the rutted areas

around RVs with pooled water and mud making a boot scrapper a useful addition to many

platforms. As a result, these platforms serve alongside mudroom enclosures in a transition

between the realm of hard, dirty work and efforts to create cleaner, tidier, domestic spaces.

Similarly, objects commonly found on platforms, though lacking lock or security, are

also insinuated as separate from public space. Objects that do not fit easily within the

confined spaces of an RV or small mobile home including appliances, propane tanks,

outdoor cooking and dining wares, and hoarded building materials are left on the platform

to unclutter the precious interior space. Electrical generators are also common and speak to

the unpredictability of electricity in many of the informal communities. Refrigerators and

freezers often stand on makeshift platforms outside the RV preserving bulk food purchases

and reinforcing the private and secure character of the platform area. These elevated

platforms also provide an intermediary surface for outdoor household activities, such as

grilling, dining, or simply sitting, associated with the American deck. Beyond their practicality,

they convey the casual comforts of outdoor--archetypically suburban--life.

A particularly curious adaptation of the platform occurs in the unique context of the

indoor RV Park outside of Watford City. The indoor RV Park is a series of large garages that

provide indoor parking for RVs. Each garage consists of a heated room with a gravel floor

and enough space for two RVs. Some residents build platforms inside the garage unit to serve

as elaborate outdoor spaces. Elaborate platforms include dining tables, sitting areas, shelving

units for overflow storage, and even areas set aside for domestic display. Even in a situation

where the risk of mud and snow are not as immediate, platforms provide an extension of the

domestic space of the RV.

The constructions of platforms and paths represent another example of significant

investment in temporary housing particularly since they are usually left behind by departing

residents. These additions contribute to the anchored character of the RV, the allusion of

semi-private space, and the convivial sociality akin to a suburban deck. In addition to the

social uses and cues, like enclosure and insulation, these spaces provided practical solutions

including storage and efforts to mitigate the mud, dirt, puddles, and snow common in the

camps.

Demarcated Property.

In most informal workforce housing sites in the Bakken, residents rationally park

their RVs or mobile homes as close as possible to a boundary of their lot leaving the rest of

12

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

the lot open for enclosures and platforms. The placement of the RV, the construction of a

mudroom, and the building of a deck or elevated path all serve to define spaces that serve a

variety of functions (Fig. 11). To reinforce the separate and private nature of this space,

some residents build fences from shipping pallets or other scrap wood present at the camp,

while others use light-duty, manufactured fencing. Railroad ties, stones, potted plants, and

prefabricated storage sheds likewise function to create demarcated space adjacent to the RV.

In more formally organized RV parks, long, narrow lots anchored on one end by

hook-ups and at the other by road access, encourage residents to locate their RVs set back

from the road. This arrangement creates a set-back and--even in these highly temporary

settlements--residents frequently adopt the traditional suburban characteristics of a front

yard. Some of the most elaborate lots have landscaped yards complete with gardens, and

even planted trees. One resident created flower gardens out of plastic flowers which she

dutifully rotated according to the seasons (Personal Interview, Debbie Skeanes, MC 75, May,

2015). The character of the landscaping is opportunistic, of course. For example,

neighboring RVs with well-kept lawns belonged to a landscaping company who appropriated

surplus turf to upgrade their surroundings. It is worth noting, however, that well-manicured

yards were almost always left to decay when a lot changed hands. In contrast to efforts to

maintain the front of the RV, the back of the RV, usually around the electrical mast and

water hook up, often becomes a place for storage of scrap wood, insulation, gas cans,

broken objects, PVC pipes, and other items that are unsightly and not of immediate use. In

more than one camp, the space between hook-ups in the back of lot is referred to as an

alley.

Demarcating property did not function exclusively in the service of mimicking

suburban domesticity. Defined lots also created spaces for work and storage of work related

objects. Truck tires, equipment, spare parts and tools, and work-related trailers reveal the

tensions between suburban practices and the practical requirements of work in informal

workforce housing. As a result, efforts to demarcate property did not always conform to

traditional suburban ideals of distinguishing between work and domestic spaces, but instead

blurred the distinction between wage labor and private life.

Less formal RV parks, often arrange smaller lots in more irregular ways making it

difficult for residents to define private space around their RVs. In one of the least formal

settlements--occupied by squatters clustered in a wooded area lacking water or electric hookups--residents built their camp around a common space where they shared tasks like cooking,

storing water, and cleaning up after meals. While this arrangement was unusual in the later

years of the boom, it hints at the outlaw character more prevalent during the early years of

the boom that may have relieved residents from opportunities, the need, or the

responsibilities to define private space.

The positioning of the unit, accompanying enclosures, elevated paths, and platforms,

all play a key role in demarcating personal space in the Bakkens informal settlements where

housing and ownership of private property are rarely aligned (Mukhija and Loukaitou-Sideris

2014). Indeed, one of the most remarkable aspects of man camp life is this interplay between

13

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

the temporary character of most settlements and the willingnesseven the insistence--of

residents to negotiate domestic space and reinforce some sense of fixed domesticity.

Objects of Social Ritual. Moveable goods contribute as much to the formation and

presentation of identity in the archaeological record as the manipulation of space and

architecture. The presence and display of particular goods around the exterior of the RV in

the workforce-housing site produce meaning that transcends functional qualities. Many of

the most bulky objects mark the location of a specific activity at the intersection of practical

needs associated with RV life. Despite the casual nature of the placements, there are

underlying attempts to personalize and even advertise the identity of the resident. The

objects become icons of the function that they serve, and by extension, the social space that

they create. The assemblage of common moveable goods around housing units provide

insight into the gendered spaces that play such an important role in the publics view of

these settlements as man camps. This perception often brings with it some hostile baggage

and this perhaps accounts for policies present in the more formal camps that prohibit

personal objects in public spaces.

It is not uncommon for units in the informal settlements to feature weight training

equipment set on either the platforms outside of the RVs or in close proximity to the unit.

From a practical perspective, the weights are too heavy to steal and too bulky to keep inside

the RV, and the cramped conditions inside the RV make exercise difficult. Additionally, their

physical form becomes their security. In the context of an RV park, the weights evoke the

performance of weight lifting and present a hyper-masculine identity for residents (Fig. 12)

(Green 1986). In an ironic counterpoint, they are often left behind when the occupant

moves on or returns home where such conspicuous displays of masculinity may return to

interior space outside of the public gaze.

Even more common than free weights were grills, often set atop a platform creating

a private space for social eating. Like the weights, the grill embodies the iconography of male

cooking and bonding over the preparation of meat (Dummitt 1998; Miller 2010). The

presence of the grill and the practice of grilling register a mastery of a particular kind of

public cooking and socialization (Fig. 13). Historically, grilling outside developed in the postwar period as men became more involved in domestic life after the social disruptions of the

World War. Grilling outside became an acceptable place for men to be involved in the

otherwise feminine household task of cooking. Of further relevance to man camp living, the

grill also became a context for the performance of masculinity at a time when houses were

becoming smaller and the exterior space of the house increasingly accommodated social

activities.

The nearly ubiquitous presence of folding furniture further echoes the backyard

barbecue and an additional solution to expanding the limited space for socialization within

the RV and to establishing a place for male bonding rituals common to cook outs,

campsites, and tailgating at football games. Like the dumbbells, these items are used for only

a short time as tools, but then, left outside, they become visible cultural and identity markers

even when their owner is absent. The weight bench, camping furniture, and the barbecue

14

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

become icons of the male absent at work, and reinforce the space of workforce housing as

evoking the space of work in the domestic realm.

Of course, the masculine encoding of the temporary workforce housing has both

limits and ambiguities. For example, there are pragmatic ways to understanding outdoor

cooking. The lack of extensive or spacious kitchens for social cooking in most RVs and the

heat of indoor cooking during warmer months complicates an exclusively masculine reading

of outdoor cooking. Hints of a more traditional model of domestic life appear throughout

the camps. As noted, some units had small vegetable gardens and even ornamental plantings.

Visits to camps during summer months reveal childrens play areas including small pools,

bikes, toys, and other aspects of family life. According to a woman employed at a large RV

Park, increasingly, year round, men are bringing their women and children out to the patch

(Personal Interview, Hollman and Collins, August 2013). Many informal workforce housing

sites have play areas for children, and common areas at larger camps become social areas for

any women present who are not employed in the Bakken.

Nonetheless, there is a reason that the sometimes inaccurate term man camp has

such currency, especially in the popular imagination. The objects associated with the

performance of masculinity at workforce housing sites reinforces the traditionally masculine

nature of work in extractive industries. The danger associated with extractive industries, their

location on the periphery, and the dirty physicality of work in mines, oil rigs, and forests of

the American West embody a historical masculinity connecting to frontier myths and

realities (Baron 2006). In the 21st century Bakken, this masculinity is reinforced by the

association of the oil industry with American strategic interests, and the prominent

appearance of American flags evokes military practice. At least superficially, oil workers in

the Bakken are hypermasculine domestic soldiers committed to national strategic interests.

The grill, free weights, and the outdoor life of informal workforce housing provide

surprising markers of both the thinly veiled tensions and the stark realities surrounding

domestic efforts amid the Bakkens fluid economy.

Conclusion

Archaeological investigation of contemporary workforce housing in the Bakken oil

patch provides an avenue for understanding the negotiation of domesticity and informal

settlement at a global periphery. The informality, contingency, and the practical realities of

life in these settlements shape a particular engagement with many aspects of American

domesticity. In the U.S., traditional domestic architecture, characteristic of the American

suburb for most of the second half of the 20th century, reveals the guiding hands of

architects, builders, and local building codes and standards. In the workforce housing of

western North Dakota, the Bakken bricoleur relies upon informal social networks, ad hoc

interventions, and salvaged material to establish the fixity of the RV and to make it more

suitable as a year-round residence. In multiple interviews, residents stated that these

modifications to their RVs make them more like home. This acknowledgment of the

15

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

ersatz domestic character of temporary housing in the Bakken supports our reading of the

architecture and material culture of these settlements as they take on key physical aspects of

suburban life, while preserving their informal and contingent character.

Our work, of course, goes beyond confirming the ethnographic accounts, and

locates the informal workforce housing in a global context. The increasingly decentered

nature of both economic capital and markets, particularly in extractive industries, coincide

with the limited infrastructure and sparse population in the Bakken counties to locate it at a

global periphery. The Bakken counties also represent a historical frontier, which has

attracted short-term settlement and economic migrants throughout the 19th and 20th

centuries. The limited economic and political resources in the region have influenced the

structure of settlement in the 21st century. Informal workforce housing sites developed just

outside the jurisdiction of the small communities throughout the region, and this allowed ad

hoc housing practices to flourish with minimal enforcement of building codes or other

forms of legal authority. As the number and variety of camps increased, some sites have

attempted to enforce largely aesthetic guidelines for architectural additions, but these policies

are enforced irregularly. Among these guidelines is the idea that architectural additions

cannot prevent the easy removal of the RV from its lot. It is telling that local residents often

construct their own privilege in the Bakken counties by pointing to the permanence of their

communities in contrast to the impermanence of workforce housing. And this

impermanence--including the related realities that stifle connections to community, both

inside and in relation to the population outside the rutted camp boundariesis a clear

consequence of temporary workforce housing.

16

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Works Cited

AUDC, Robert Sumrell, and Kazys Varnelis

2007 Blue Monday: Stories of Absurd Realities and Natural Philosophies, Barcelona: Actar

Editorial.

Bangsund, Dean, Nancy Hodur, Richard Rathge, and Karen Olson

2012 Modeling Employment, Housing, and Population in Western North Dakota: The

Case of Dickinson. Agribusiness and Applied Economics Report 695. Fargo, N.D.

Accessed on August 7, 2014.

http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/133390/2/AAE695.pdf

Barrett, Grant.

2012. "The Words of 2012," The New York Times Sunday Review (December 22, 2012).

Baron, E.

2006. Masculinity, the Embodied Male Worker, and the Historians Gaze, International

Labor and Working-Class History 69, 143160

Brown, C.

2013. North Dakota Went Boom, New York Times Magazine (January 31, 2013).

Chase-Dunn, Kawano, Brewer

2000 Trade Globalization since 1795: Waves of Integration in the World-System" American

Sociological Review 65.1, 77-95

Dalrymple, Amy

2012 Oil Patch Dispatch, Forum Communications Blog, posted May 24, 2012.

Drury, Margaret J.

1972 Mobile Homes; The Unrecognized Revolution in American Housing, New York:

Praeger

Dummitt, Chris.

1998 Finding a Place for Father: Selling the Barbecue in Postwar Canada, Journal of the

Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Socit historique du Canada 9, 209223.

Duncan, J.S. and N.G. Duncan.

2004 Landscapes of Privilege: The Politics of the Aesthetic in an American Suburb. New

York and London: Routledge.Garner 2012

Gold, Russell.

2014. The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the

World. New York : Simon & Schuster.

Gorney, Cynthia

17

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

2014

Far from Home. Millions of guest workers toil in oil-rich countries, cut off from

both locals and loves ones, National Geographic 225:1 (Jan. 2014), pp. 70-95.

Green, H.

1986 Fit for America: Health, Fitness, Sport, and American Society. New York: Pantheon

Books.

Graves-Brown, Paul and John Schofield

2011 The filth and the fury: 6 Denmark Street (London) and the Sex Pistols, Antiquity

85. 1385-1401.

Hailey, Charlie

2008 Campsites: Architecture of Duration and Place, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press.

Hailey, Charlie

2009 Camps: A Guide to 21st Century Space, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hardesty, Donald L. 1988. The Archaeology of Mining and Miners: A View from the Silver

State, Pleasant Hill, Cal.: Society for Historical Archaeology

Hart, John Fraser, Michelle J. Rhodes, and John Morgan

2002 The Unknown World of the Mobile Home, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press.

Heath, Kingston W.

2007 Assessing Regional Identity Amidst Change: The Role of Vernacular Studies,

Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 13:2, pp. 76-94.

Hodur, Nancy and Dean Bangsund

2013 Williston Basin 2012: Projections of Future Employment and Population North

Dakota Summary. Agribusiness and Appl ied Economics Report 704. Fargo, N.D.

Accessed on August 7, 2014.

http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/142589/2/AAE704%20web%20.pdf

Jackson, J. B.

1953 The Westward-Moving House. Landscape 2.3, 8-21.

1960

"The Four Corners Country." Landscape 10, 20-26.

1984

The Moveable Dwelling and How It Came to America, in Discovering the

Vernacular Landscape, 91-101, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kiddey, Rachael and J. Schofield

2011 Embrace the Margins: Adventures in Archaeology and Homelessness, Public

Archaeology 10.1. 4-22.

Kiddley and Schofield

18

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

2014 Turbo Island, Bristol: excavating a contemporary homeless place. Post-Medieval

Archaeology 48.1. 133-150.

Knapp, A. Bernard

1998 The Social Approaches to the Archaeology and Anthropology of Mining, in A.

Bernard Knapp, Vincent C. Pigott, and Eugenia W. Herbert eds. Social Approaches

to an Industrial Past: The Archaeology and Anthropology of Mining. London and

New York: Routledge. 1-23.

2003 The Archaeology of Community on Bronze Age Cyprus: Politiko Phorades in

Context, American Journal of Archaeology 107.4. 559-580.

Kollars, Nina A.

2014. Wars Horizon: Soldier-Led Adaptation in Iraq and Vietnam, Journal of Strategic

Studies (January 3, 2015) Lawrence 1998

Lawrence, S.

1998 Gender and community structure on Australian colonial goldfields." in A. Bernard

Knapp, Vincent C. Pigott, and Eugenia W. Herbert eds. Social Approaches to an

Industrial Past: The Archaeology and Anthropology of Mining. London and New

York: Routledge. 39-58.

1999

"Towards a feminist archaeology of households: Gender and household structure on

the Australian goldfields." In P. M. Allison ed., The Archaeology of Household

Activities London and New York: Routledge 1999. 121-141.

Miller, T.

2010 The Birth of the Patio Daddy-O: Outdoor Grilling in Postwar America, Journal of

American Culture 33, 5-11.

Mitchell, Don.

2012 La Casa de Esclavos Modernos : Exposing the Architecture of Exploitation,

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71, pp. 451-461.Myers 2010

Mrozowski, Stephen A.

1991 Landscapes of Inequality, in The Archaeology of Inequality, ed. Randall H.

McGuire and Robert Paynter, pp. 79-101, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Study of Lowell,

Mass.

Mukhija, Vinit and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris eds.

2014 The Informal City: Beyond Taco Trucks and Day Labor. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press.

North Dakota Petroleum Council

2011 E-News December 2011, North Dakota Petroleum Council (December 14, 2011),

retrieved from. http://www.ndoil.org/?id=214&ncid=9&nid=188.

Perlman, Janice

19

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

2010

Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro, Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Porter, K.

2009 North Dakota: 1960 to the Millennium. Dubuque, Iowa : Kendall/Hunt Publishers.

Robinson, Elywn

1966 The History of North Dakota. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Rothaus, Richard

2013 Return on Sustainability: Workforce Housing for People, Planet and Profit, Target

Logistics White Paper 08.13. Accessed August 7, 2014:

http://www.targetlogistics.net/1_pdfs/whitepapers/ReturnOnSustainability.WorkforceHousingForPeoplePlanetAndProfit.pdf

Rosner, Daniela and Jonathan Bean.

2009 Learning from IKEA Hacking: Im Not One to Decoupage a Tabletop and Call It

a Day, Proceedings of Computer Human Interaction Conference 2009, April 4-9,

2009, Boston, Mass.Rothaus 2014

Shackel, Paul A.

2009 The Archaeology of American Labor and Working-Class Life, Gainesville: University

Press of Florida.

Schofield, John and Mike Anderton

2000 The queer archaeology of Green Gate: Interpreting contested space at Greenham

Common Airbase, World Archaeology 32.2. 236-251.

Simone. AbdouMaliq

2004 For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities, Durham: Duke

University Press.

Tauxe, Caroline S.

1993 Farms, Mines, and Main Street: Uneven Development in a Dakota County,

Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Taylor, A.

2013 North Dakotas Oil Boom, In Focus. (March 13, 2013). Accessed December 2,

2015: http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/03/north-dakotas-oilboom/100473/

Thornburg, David

1991 A Galloping Bungalows. The Rise and Demise of the American House Trailer,

Hamden.

Van Buren, Mary and J. M. Weaver

20

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

2012

Contours of Labor and History: A Diachronic Perspective on Andean Mineral

Production and the Making of Landscapes in Porco, Bolivia, Historical Archaeology

46.3. 79-101.

Van Bueren, Thad. M.

2002 The Changing Face of Work in the West: Some Introductory Comments,

Historical Archaeology 36.3. 1-7.

Van Slyck, Abigail A.

2010 A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth,

1890-1960, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Wallis, Allan D.

1991 Wheel Estate: The Rise and Decline of Mobile Homes, New York: Oxford

University Press.

Ward, Peter M. ed.

1982. Self-Help Housing: A Critique, London: Mansell Publishing Limited.

Ward, Peter M.

1999. Colonias and public policy in Texas and Mexico: Urbanization by stealth. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Ward, Peter. 2014. The Reproduction of Informality in Low-Income Self-Help Housing

Communities, in The Informal City: Beyond Taco Trucks and Day Labor, ed. Vinit

Mukhija and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, pp. 59-77. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press

White, Roger B.

2000 Home on the Road: The Motor Home in America, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian.

Wright, Gwendolyn

1981 Housing Factory Workers, and Welfare Capitalism and the Company Town, in

Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, pp. 58-72, 177-192,

New York.: Pantheon Books.

Zimmerman, Larry

2010 Activism and creating a translational archaeology of homelessness, World

Archaeology 42.3. 443-454.

21

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figures:

Figure 1: Map of Bakken (will be replaced with a proper map!)

22

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 2: Workforce Housing in the Bakken

23

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 3: Type 1 Camps

24

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 4: Type 2 Camps

Figure 5: Type 3 Camps

25

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 6: Man Camps around Existing Settlements

26

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 7: Insulation

Figure 8: Woodframes for insulation

27

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 9: Mudroom

Figure 10a: External platforms (Photo and drawing?)

28

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 10b: (a) grill (b) cooler (c) camp chairs (d) propane cylinder (e) camp table (f) shipping

pallet (g) deck.

29

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 11: Demarcated property.

Figure 12: weights

30

WORKING DRAFT. DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHORS PERMISSION.

Figure 13: Grills

31

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Lessons From The Bakken Oil PatchDokumen20 halamanLessons From The Bakken Oil PatchbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- The Bakken: An Archaeology of An Industrial LandscapeDokumen24 halamanThe Bakken: An Archaeology of An Industrial LandscapebillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- An Epilogue To The Tourist Guide To The Bakken Oil PatchDokumen10 halamanAn Epilogue To The Tourist Guide To The Bakken Oil PatchbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Joel Jonientz, "How To Draw... Punk Archaeology"Dokumen11 halamanJoel Jonientz, "How To Draw... Punk Archaeology"billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow Archaeology: Technology, Efficiency, and Archaeological WorkDokumen16 halamanSlow Archaeology: Technology, Efficiency, and Archaeological WorkbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow Archaeology, Version 4Dokumen12 halamanSlow Archaeology, Version 4billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Ontology, World Archaeology, and The Recent PastDokumen15 halamanOntology, World Archaeology, and The Recent PastbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow ArchaeologyDokumen14 halamanSlow Archaeologybillcaraher100% (1)

- The Archive (Volume 6)Dokumen548 halamanThe Archive (Volume 6)billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Caraher Archaeology of and in The Contemporary WorldDokumen11 halamanCaraher Archaeology of and in The Contemporary WorldbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow ArchaeologyDokumen11 halamanSlow ArchaeologybillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Butrint 4Dokumen3 halamanReview of Butrint 4billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- The Archive (Volume 5)Dokumen733 halamanThe Archive (Volume 5)billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- One Hundred Years of PeaceDokumen28 halamanOne Hundred Years of PeacebillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Man Camp Dialogues Study GuideDokumen1 halamanMan Camp Dialogues Study GuidebillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- PKAP IntroductionDokumen23 halamanPKAP IntroductionbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- The University in The Service of SocietyDokumen33 halamanThe University in The Service of SocietybillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowDokumen5 halamanIntroduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Punk ArchaeologyDokumen234 halamanPunk Archaeologybillcaraher100% (3)

- Visions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean ArchaeologyDokumen125 halamanVisions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean Archaeologybillcaraher100% (1)

- North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsDokumen59 halamanNorth Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Michael Dixon's Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Corinth, 138-196 BCDokumen2 halamanReview of Michael Dixon's Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Corinth, 138-196 BCbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow Archaeology Version 2Dokumen14 halamanSlow Archaeology Version 2billcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Slow ArchaeologyDokumen12 halamanSlow ArchaeologybillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Artifact and Assemblage at Polis-Chrysochous On CyprusDokumen73 halamanArtifact and Assemblage at Polis-Chrysochous On CyprusbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Settlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesDokumen26 halamanSettlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Imperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradeDokumen29 halamanImperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradebillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- The Archaeology of Man-Camps: Contingency, Periphery, and Late CapitalismDokumen13 halamanThe Archaeology of Man-Camps: Contingency, Periphery, and Late CapitalismbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- Settlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesDokumen17 halamanSettlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesbillcaraherBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- 1.1.1 Adverb Phrase (Advp)Dokumen2 halaman1.1.1 Adverb Phrase (Advp)mostarjelicaBelum ada peringkat

- Solidworks Inspection Data SheetDokumen3 halamanSolidworks Inspection Data SheetTeguh Iman RamadhanBelum ada peringkat

- Get 1. Verb Gets, Getting Past Got Past Participle Got, GottenDokumen2 halamanGet 1. Verb Gets, Getting Past Got Past Participle Got, GottenOlga KardashBelum ada peringkat

- Marlissa - After School SpecialDokumen28 halamanMarlissa - After School SpecialDeepak Ratha50% (2)

- Tong RBD3 SheetDokumen4 halamanTong RBD3 SheetAshish GiriBelum ada peringkat

- Business Law Module No. 2Dokumen10 halamanBusiness Law Module No. 2Yolly DiazBelum ada peringkat

- Detailed Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Areas Teaching Dates and Time QuarterDokumen5 halamanDetailed Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Areas Teaching Dates and Time QuarterKhesler RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Battery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910Dokumen4 halamanBattery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910b400013Belum ada peringkat

- UNIT 2 - Belajar Bahasa Inggris Dari NolDokumen10 halamanUNIT 2 - Belajar Bahasa Inggris Dari NolDyah Wahyu Mei Ima MahananiBelum ada peringkat

- Digi-Notes-Maths - Number-System-14-04-2017 PDFDokumen9 halamanDigi-Notes-Maths - Number-System-14-04-2017 PDFMayank kumarBelum ada peringkat

- Autos MalaysiaDokumen45 halamanAutos MalaysiaNicholas AngBelum ada peringkat

- Inline check sieve removes foreign matterDokumen2 halamanInline check sieve removes foreign matterGreere Oana-NicoletaBelum ada peringkat

- NBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Dokumen49 halamanNBPME Part II 2008 Practice Tests 1-3Vinay Matai50% (2)

- Kids' Web 1 S&s PDFDokumen1 halamanKids' Web 1 S&s PDFkkpereiraBelum ada peringkat

- Architectural PlateDokumen3 halamanArchitectural PlateRiza CorpuzBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateDokumen22 halamanChronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateJose Miranda ChavezBelum ada peringkat

- Auto TraderDokumen49 halamanAuto Tradermaddy_i5100% (1)

- Adic PDFDokumen25 halamanAdic PDFDejan DeksBelum ada peringkat

- Contextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelDokumen15 halamanContextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelHartoyoBelum ada peringkat

- Javascript The Web Warrior Series 6Th Edition Vodnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDokumen31 halamanJavascript The Web Warrior Series 6Th Edition Vodnik Test Bank Full Chapter PDFtina.bobbitt231100% (10)

- Technical Contract for 0.5-4X1300 Slitting LineDokumen12 halamanTechnical Contract for 0.5-4X1300 Slitting LineTjBelum ada peringkat

- BI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014Dokumen1 halamanBI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014scribdBelum ada peringkat

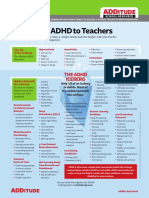

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDokumen1 halamanExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Advanced VLSI Architecture Design For Emerging Digital SystemsDokumen78 halamanAdvanced VLSI Architecture Design For Emerging Digital Systemsgangavinodc123Belum ada peringkat

- Supply Chain AssignmentDokumen29 halamanSupply Chain AssignmentHisham JackBelum ada peringkat

- Mundane AstrologyDokumen93 halamanMundane Astrologynikhil mehra100% (5)

- A Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan NajafiDokumen9 halamanA Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan Najafiinfo3814Belum ada peringkat

- Barra de Pinos 90G 2x5 P. 2,54mm - WE 612 010 217 21Dokumen2 halamanBarra de Pinos 90G 2x5 P. 2,54mm - WE 612 010 217 21Conrado Almeida De OliveiraBelum ada peringkat

- Microsoft Word - G10 Workbook - Docx 7Dokumen88 halamanMicrosoft Word - G10 Workbook - Docx 7Pax TonBelum ada peringkat

- Independent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentDokumen96 halamanIndependent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentBarbara MillerBelum ada peringkat