Holy 3

Diunggah oleh

Holy Fitria ArianiJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Holy 3

Diunggah oleh

Holy Fitria ArianiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

CLINICAL

Flashes and floaters

A practical approach to assessment and management

Shyalle Kahawita

Sumu Simon

Jolly Gilhotra

Background

Flashes and floaters are common ophthalmic issues for which patients may

initially present to their general practitioner. It may be a sign of benign,

age-related changes of the vitreous or more serious retinal detachment.

Objective

This article provides a guide to the assessment and management of a patient

presenting with flashes and floaters.

Discussion

Although most patients presenting with flashes and floaters have benign

age-related changes, they must be referred to an ophthalmologist to rule out

sight-threatening conditions. Key examination features include the nature of the

flashes and floaters, whether one or both eyes are affected and changes in visual

acuity or visual field.

Keywords

eye diseases; vision disorders

The incidence of retinal detachment is

one in 10 000 people per year and hence

is a relatively rare event.1 The symptoms,

however, are not specific to retinal

detachment and therefore differentiation

from other ophthalmic conditions is difficult

without a dilated fundus examination.2,3 The

urgency for referral to an ophthalmologist

is to exclude retinal detachment as well as

identify and treat retinal tears in patients

with high-risk posterior vitreous detachment.

Pathophysiology

Floaters refer to the sensation of dark spots that are

caused either by opacities in the vitreous, which

cast shadows on the retina, or by light bending at

the junction between fluid pockets and the vitreous.4

Floaters may be caused by vitreous debris from

infection, inflammation and haemorrhage, but are

typically due to the age-related degeneration of the

vitreous, forming condensations of collagen fibres.

Patients may describe floaters as flies, cobwebs

or worms that are more pronounced against

light backgrounds. Floaters may also result from

haemorrhage of retinal vessels into the vitreous and

may be described as minute black or red spots. The

most common cause of vitreous haemorrhage is

proliferative diabetic retinopathy.5

Flashes are visual phenomena known as

photopsias and refer to the perception of light in the

absence of external light stimuli. Photopsias can be

generated anywhere along the visual pathway, but

in the eye they result from mechanical stimulation

of the retina by vitreoretinal traction. Flashes are

typically described as a momentary arc of white light,

similar to a bolt of lightning or a camera flash. They

are more noticeable in dim lighting, may be triggered

by eye movement and are usually in the temporal

visual field.

Posterior vitreous

detachment

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is the most

common cause of acute onset of flashes and floaters,

present in nearly 66% of patients over 70 years.4,6

It is an age-related change in which the vitreous

degenerates, shrinks and separates from the retina.

During separation, the vitreous may tug and cause

mechanical stimulation of the retina, resulting in

flashes. Clinically, the patient has normal vision, no

visual field defects and no relative afferent pupillary

defect.4,7

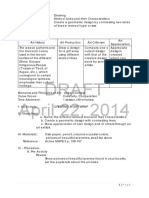

A patient with posterior vitreous detachment is

deemed to be at higher risk of retinal detachment if it

is associated with vitreous haemorrhage; about 70%

of these patients have been found to have at least

one retinal tear8 (Figure 1).

Retinal tear

Of PVD, 14% cause a tear in the retina during

separation.4 Clinically, the patient has no visual field

defect and no relative afferent pupillary defect. The

REPRINTED FROM AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 43, NO. 4, APRIL 2014 201

CLINICAL Flashes and floaters: a practical approach to assessment and management

Figure 1. Vitreous haemorrhage associated

with posterior vitreous detachment

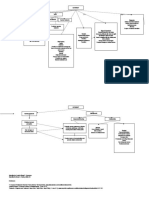

Figure 2. Retinal tear associated with

rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

patient may complain of black or red spots and

impaired vision if the tear has disrupted a blood

vessel, resulting in vitreous haemorrhage or release

of retinal pigment epithelium.4,9

(severe acute hypertension), inflammation or

neoplasm.13

Retinal detachment

Approximately 3346% of patients with a retinal

tear or hole will develop a rhegmatogenous retinal

detachment.10 Fluid from the vitreous is able

to pass through the tear underneath the retina,

separating it from the retinal pigment epithelium

(Figure 2). Detachment can progress as more fluid

enters through the retinal break. Detachment

results in visual field loss as the photoreceptors

become severely damaged by separation from their

underlying choroidal vascular supply. For example,

a superior retinal detachment will result in an

inferior visual field defect. Patients may describe

a shadow or a curtain coming down over their

vision. If the macula is detached, central visual

acuity is lost and this is typically permanent6

(Figure 3).

The most common location for a retinal tear is in

the superotemporal quadrant (60%) and because of

the effects of gravity results in a greater incidence

of macula-off retinal detachment, compared with

inferior or nasal retinal tears.11,12

Other types of retinal detachment include

tractional and exudative and these can also

present with flashes and floaters. Tractional

retinal detachment is caused by mechanical

forces on the retina, usually as a result of previous

haemorrhage, infection, inflammation, trauma or

surgery. Exudative retinal detachment results from

accumulation of fluid in the potential sub-retinal

space due to disruption of hydrostatic forces

202 REPRINTED FROM AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 43, NO. 4, APRIL 2014

Assessment

1. History: to help differentiate ocular from nonocular causes of flashes and floaters (Table 1)

2. Examine the eye:

a. visual acuity of each eye separately and

with glasses or pinhole

b. visual fields to confrontation

c. pupil response for relative afferent

pupillary defect (RAPD)

Direct ophthalmoscopy alone is not enough as most

retinal tears or detachment are in the periphery; the

patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist at

this point. Dilating eye drops take 1015 minutes to

take effect and as there is a small risk of triggering

acute-angle closure glaucoma, pupil dilation is not

ideal in a general practice setting.14,15

General practitioners in rural areas may have

limited access to an ophthalmologist; hence those

with experience in ultrasonography may be able

to determine the presence or absence of ocular

pathology. A study assessing the accuracy of

bedside ocular ultrasonography in 61 patients in

an emergency department showed a sensitivity of

100% and a specificity of 8397.2%.16,17

Referral guidelines

Patients with symptoms of acute onset flashes

or floaters and visual field loss need same day

referral to an ophthalmologist for a dilated

fundus examination, to rule out retinal tears and

retinal detachment.6,9

Longstanding flashes or floaters require nonurgent ophthalmology review.10

Figure 3. Retinal detachment superiorly

(optic disc visible in the background)

Treatment by an

ophthalmologist

PVD in itself does not require treatment.

Depending on the clinical scenario, patients

may be re-examined by the ophthalmologist at

6 weeks, as 3.4% will have a new retinal tear. If

the patient complains of a new shower of flashes

and floaters, or reduction in vision, they should be

reviewed sooner.3,4

If the PVD is associated with retinal tears, they

need prompt treatment to prevent progression

to retinal detachment. Usually, breaks are

surrounded with laser or cryo burns to create a

chorioretinal scar that prevents fluid seeping into

the sub-retinal space.6

PVD associated with retinal detachment

needs vitreoretinal management. These include

vitrectomy, pneumatic retinopexy and scleral

buckling with endolaser or cryopexy.6 A vitrectomy

aims to relieve vitreoretinal traction on the

retinal tear by removing the vitreous. Pneumatic

retinopexy is a procedure where an intravitreal

gas bubble is used to seal a retinal break and

reattach the retina. For scleral buckling, a band

is placed on the exterior surface of the globe,

indenting the sclera so that vitreoretinal traction

is reduced.13

If the macula was not detached before surgery,

visual acuity will be maintained. If the macula

was detached before surgery, final visual recovery

depends on the duration and degree of elevation

of macular detachment and the patients age.

Surgery, therefore, is more urgently indicated in

patients with preserved visual acuity. Surgery is

routinely done in patients whose macula detached

within a week.13

Flashes and floaters: a practical approach to assessment and management CLINICAL

Key points

Flashes and floaters are usually signs of

benign disease; however, a small percentage

will have sight-threatening disease and

hence all patients require a dilated fundus

examination.

If symptoms of acute onset flashes and

floaters are present urgent same day referral

is required.3,4

Acute-onset flashes and floaters with

visual field defect are suggestive of retinal

detachment.

Authors

Shyalle Kahawita MBBS, Ophthalmology

Resident Ophthalmology Department, Queen

Elizabeth Hospital, Adelaide, SA. s.kahawita@

gmail.com

Sumu Simon MBBS, MS, FRANZCO, Medical

Retinal Fellow Ophthalmology Department,

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Adelaide, SA

Jolly Gilhotra MBBS, M.Med (Clinical

Epidemiology), FRANZCO, Associate Professor,

Ophthalmology Department, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Adelaide, SA.

Competing interests: Jolly Gilhotra is a paid

board member of Alcon and has received

payment for consultancy, expert testimony, lectures, manuscript preparation, travel expenses,

accommodation and has grants pending

from Bayer Pharmaceuticals and Novartis

Pharmaceuticals.

Table 1. Differential diagnoses

Flashes

Ophthalmic

Posterior vitreous detachment

Retinal tear/hole

Retinal detachment

Optic neuritis photopsia on eye movement, retrobulbar pain

Non-ophthalmic

Migraine scintillating scotomas, coloured lights, bilateral, evolves over 5 to 30

minutes before resolving with onset of a headache, normal visual acuity

Postural hypotension bilateral temporary dimming of vision and

light-headedness

Occipital tumours

Vertebrobasilar transient ischaemic attacks

Floaters

Ophthalmic

Vitreous syneresis

Vitreous haemorrhage

Posterior vitreous detachment

Retinal detachment

Vitritis

Tear film debris

Table 2. Risk factors for retinal detachment1

Myopia (near sightedness) the length of the eye and vitreoretinal forces are

greater than normal and also the retina is thinner and more prone to breaks

Trauma compression and decompression forces may generate sufficient

vitreoretinal traction to produce retinal tears

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned;

externally peer reviewed.

Cataract surgery detachment of the vitreous is accelerated

Acknowledgements

Advancing age degeneration of the vitreous increases with time

The authors would like to thank Anton Drew,

ophthalmic photographer at the Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, for the retinal photographs.

References

1. Pokhrel PK, Loftus SA. Ocular emergencies. Am Fam

Physician 2007;76:82936.

2. Polkinghorne PJ, Craig JP. Analysis of symptoms

associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2004;32:60306.

3. Dayan MR, Jayamanne DG, Andrews RM, Griffiths

PG. Flashes and floaters as predictors of vitreoretinal

pathology: is follow-up necessary for posterior vitreous detachment? Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 4):45658.

4. Johnson D, Hollands H. Acute-onset floaters and

flashes. CMAJ 2012;184:431.

5. Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Vitreous Hemorrhage.

Surv Ophthalmol 1997;42:339.

6. Gariano RF, Kim CH. Evaluation and management of

suspected retinal detachment. Am Fam Physician

2004;69:169198.

7. Nagendran ST, Thomas D, Gurbaxani A. Flashes, floaters and fuzz. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2013;74:9195.

Previous retinal detachment surgery

8. Sarrafizadeh R, Hassan TS, Ruby AJ, et al. Incidence

of retinal detachment and visual outcome in eyes

presenting with posterior vitreous separation and

dense fundus-obscuring vitreous hemorrhage.

Ophthalmology 2001;108:227378.

9. Diamond JP. When are simple flashes and floaters

ocular emergencies? Eye (Lond) 1992;6(Pt 1):10204.

10. Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel

DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is

this patient at risk for retinal detachment? JAMA

2009;302:224349.

11. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 3rd edn: Elselvier

Inc.; 2009.

12. Denniston A, Murrray P. Oxford Handbook of

Ophthalmology. 2nd edn: Oxford University Press;

2009.

13. Kanski JJ. Clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach. 6th edn. Edinburgh ; New York:

Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier; 2007, vii, 931.

14. Lachkar Y, Bouassida W. Drug-induced acute

angle closure glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol

2007;18:12933.

15. Porter J. Acute-onset floaters and flashes and risk

for retinal detachment. JAMA 2010;303:1370; author

reply 1370.

16. Yoonessi R, Hussain A, Jang TB. Bedside ocular

ultrasound for the detection of retinal detachment

in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med

2010;17:91317.

17. Blaivas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. A study of

bedside ocular ultrasonography in the emergency

department. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:79199.

REPRINTED FROM AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 43, NO. 4, APRIL 2014 203

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Ageing Eye Posterior Segment ChangesDokumen6 halamanAgeing Eye Posterior Segment ChangesirijoaBelum ada peringkat

- Emergencias Oculares Affp 13Dokumen5 halamanEmergencias Oculares Affp 13Mario Villarreal LascarroBelum ada peringkat

- Vitreous Floater1Dokumen7 halamanVitreous Floater1mithaa octoviagnesBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen28 halamanRetinal DetachmentRisqi AdiyatmaBelum ada peringkat

- Racgp Floaters and Flashes OpthalmologyDokumen3 halamanRacgp Floaters and Flashes OpthalmologyBeaulah HunidzariraBelum ada peringkat

- Protrusion OjoDokumen16 halamanProtrusion OjoAntonio ReaBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal Detachment Is A Disorder of The Eye in Which The Retina Peels Away From Its Underlying Layer of Support TissueDokumen5 halamanRetinal Detachment Is A Disorder of The Eye in Which The Retina Peels Away From Its Underlying Layer of Support TissuejobinbionicBelum ada peringkat

- Primary Retinal Detachment: Clinical PracticeDokumen9 halamanPrimary Retinal Detachment: Clinical PracticeAdita DitaBelum ada peringkat

- The Gradual Loss of VisionDokumen9 halamanThe Gradual Loss of VisionWALID HOSSAINBelum ada peringkat

- Age-Related Cataract & GlaucomaDokumen26 halamanAge-Related Cataract & Glaucomasweetyeyal2002Belum ada peringkat

- Cataract LectureDokumen22 halamanCataract Lecturenashadmohammed99Belum ada peringkat

- Glaukoma Dan HipermetropiDokumen6 halamanGlaukoma Dan HipermetropifuadaffanBelum ada peringkat

- The Gradual Loss of VisionDokumen9 halamanThe Gradual Loss of VisionShubham KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Jorge G Arroyo, MD, MPH Jonathan Trobe, MD Howard Libman, MD Contributor Disclosures Peer Review ProcessDokumen13 halamanJorge G Arroyo, MD, MPH Jonathan Trobe, MD Howard Libman, MD Contributor Disclosures Peer Review ProcessLis Borda MuñozBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen21 halamanRetinal Detachmentณัช เกษมBelum ada peringkat

- LTM SenseDokumen6 halamanLTM SenseNabilla MerdikaBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen14 halamanRetinal DetachmentPui_Yee_Siow_6303Belum ada peringkat

- Cataract. Slit Lamp Photograph Cataract. Slit Lamp Photograph FollowingDokumen6 halamanCataract. Slit Lamp Photograph Cataract. Slit Lamp Photograph Followingekin_shashaBelum ada peringkat

- Primary Retinal DetachmentDokumen9 halamanPrimary Retinal DetachmentMarviane ThenBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen31 halamanRetinal DetachmentEko KunaryagiBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen32 halamanRetinal Detachmentc/risaaq yuusuf ColoowBelum ada peringkat

- Lens Iris Pupil Retina: Cataract OverviewDokumen5 halamanLens Iris Pupil Retina: Cataract Overviewrizky_kurniawan_14Belum ada peringkat

- Senile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) : Practice Essentials, Background, PathophysiologyDokumen6 halamanSenile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) : Practice Essentials, Background, PathophysiologyadliahghaisaniBelum ada peringkat

- Vitreous HemorrhageDokumen7 halamanVitreous HemorrhageindahBelum ada peringkat

- Mata Tenang Visus Turun MendadakDokumen74 halamanMata Tenang Visus Turun MendadakYeni AnggrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Retina/Vitreous: Question 1 of 130Dokumen51 halamanRetina/Vitreous: Question 1 of 130safasayedBelum ada peringkat

- 1retinal DetachmentDokumen5 halaman1retinal Detachmentsunny_jr_Belum ada peringkat

- Katara KDokumen4 halamanKatara KAmirah Jihan AfryBelum ada peringkat

- Myopic Macular Degeneration: How The Eye WorksDokumen4 halamanMyopic Macular Degeneration: How The Eye WorksVanessa HermioneBelum ada peringkat

- Senile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) Clinical Presentation - History, Physical, CausesDokumen4 halamanSenile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) Clinical Presentation - History, Physical, CausesAhmad Fahrozi100% (1)

- Senile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) Clinical Presentation - History, Physical, Causes PDFDokumen4 halamanSenile Cataract (Age-Related Cataract) Clinical Presentation - History, Physical, Causes PDFAhmad FahroziBelum ada peringkat

- Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (OR)Dokumen4 halamanExtracapsular Cataract Extraction (OR)Jet-Jet GuillerganBelum ada peringkat

- New Management Strategies For Ectopia LentisDokumen14 halamanNew Management Strategies For Ectopia LentisximoBelum ada peringkat

- Desry Sevti Eka Putri 1410070100105Dokumen11 halamanDesry Sevti Eka Putri 1410070100105Diah FebruarieBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen8 halamanRetinal DetachmentJohanLazuardiBelum ada peringkat

- Patel 2014Dokumen9 halamanPatel 2014marieBelum ada peringkat

- The Handbook of Ophthalmic EmergenciesDari EverandThe Handbook of Ophthalmic EmergenciesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (4)

- Ocular Emergencies 2017Dokumen18 halamanOcular Emergencies 2017Sebastian BarreraBelum ada peringkat

- Vitreous Floaters: Publication DetailsDokumen6 halamanVitreous Floaters: Publication Detailsmithaa octoviagnesBelum ada peringkat

- Ablasio RetinaDokumen23 halamanAblasio RetinaResa PutraBelum ada peringkat

- CataractDokumen17 halamanCataractrhopmaeBelum ada peringkat

- Vitreous Hemorrhage: Major ReviewDokumen4 halamanVitreous Hemorrhage: Major Reviewmutya yulindaBelum ada peringkat

- NCM 116: Care of Clients With Problems in Nutrition and Gastrointestinal, Metabolism and Endocrine,, Acute and ChronicDokumen18 halamanNCM 116: Care of Clients With Problems in Nutrition and Gastrointestinal, Metabolism and Endocrine,, Acute and ChronicDiego DumauaBelum ada peringkat

- CATARACT Case Senario No.1 (Tapel, Joyce T. - BSN3-E)Dokumen4 halamanCATARACT Case Senario No.1 (Tapel, Joyce T. - BSN3-E)SIJIBelum ada peringkat

- Blunt Trauma - FriskaDokumen7 halamanBlunt Trauma - FriskaAnonymous Uds7qQrBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal Detachment and HomoeopathyDokumen7 halamanRetinal Detachment and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen3 halamanRetinal DetachmentRownald Lakandula PanuncialBelum ada peringkat

- MyopiaDokumen11 halamanMyopiablueiceBelum ada peringkat

- Retinaldetachmentnew WORSDokumen51 halamanRetinaldetachmentnew WORSMuthulakshmiBelum ada peringkat

- Keratoconus: Picture 1Dokumen6 halamanKeratoconus: Picture 1BuiyiWongBelum ada peringkat

- Keratoconus: Picture 1Dokumen6 halamanKeratoconus: Picture 1BuiyiWongBelum ada peringkat

- 1 - MyopiaDokumen9 halaman1 - MyopiaSpislgal PhilipBelum ada peringkat

- KeratoconusDokumen21 halamanKeratoconusDraghici ValentinBelum ada peringkat

- Childhood Cataracts and Other JadiDokumen49 halamanChildhood Cataracts and Other JadiSania NadianisaBelum ada peringkat

- Retinal DetachmentDokumen10 halamanRetinal DetachmentSilpi HamidiyahBelum ada peringkat

- Ahmed 2010Dokumen11 halamanAhmed 2010Karamjot SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Grey Eyecare Vancouver OptometristsDokumen2 halamanGrey Eyecare Vancouver OptometristspointgreyeyeBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Practice Review Ophthalmology: in This Article..Dokumen7 halamanNursing Practice Review Ophthalmology: in This Article..intan juitaBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Field Loss in the Real World: A Book of Static Perimetry Test Targets for Eye Health ProfessionalsDari EverandVisual Field Loss in the Real World: A Book of Static Perimetry Test Targets for Eye Health ProfessionalsBelum ada peringkat

- Elements of Design 1 PDFDokumen28 halamanElements of Design 1 PDFMichaila Angela UyBelum ada peringkat

- Henderson Hollingworth 1999Dokumen30 halamanHenderson Hollingworth 1999Donald AndersonBelum ada peringkat

- Density Dan Cie LabDokumen9 halamanDensity Dan Cie LabBrata BayuBelum ada peringkat

- TG - Art 3 - Q1Dokumen36 halamanTG - Art 3 - Q1Jerame CubolBelum ada peringkat

- ND Filters Guide PDFDokumen11 halamanND Filters Guide PDFluisangelotBelum ada peringkat

- Closing and Opening: Basic Morphological AlgorithmsDokumen16 halamanClosing and Opening: Basic Morphological AlgorithmsSuchi UshaBelum ada peringkat

- Final Exam Digital Image Processing (EE-333) 1-Jul-2020Dokumen1 halamanFinal Exam Digital Image Processing (EE-333) 1-Jul-2020Anas Inam50% (2)

- Concept Map CATARACTDokumen2 halamanConcept Map CATARACTJrBong Semanero100% (1)

- ILCE-6000 4DFOCUS Camera Settings Guide PDFDokumen18 halamanILCE-6000 4DFOCUS Camera Settings Guide PDFAizat HawariBelum ada peringkat

- Adult Cataract: Cortical or Soft CataractDokumen6 halamanAdult Cataract: Cortical or Soft CataractJohn Christopher LucesBelum ada peringkat

- How To Read The Labels On Your New Paint - Anna-Carien GoosenDokumen1 halamanHow To Read The Labels On Your New Paint - Anna-Carien GoosenMohamed Abou El hassanBelum ada peringkat

- Visual Impairment ScriptDokumen3 halamanVisual Impairment Scriptapi-285548719Belum ada peringkat

- Mod 19 Reading AssignmentDokumen2 halamanMod 19 Reading AssignmentDana M.Belum ada peringkat

- Life Miniatures IIDokumen83 halamanLife Miniatures IIAlbertoBelum ada peringkat

- Original Article: The Effect of Experimentally Induced Anisometropia On Binocularity and Bifoveal FixationDokumen7 halamanOriginal Article: The Effect of Experimentally Induced Anisometropia On Binocularity and Bifoveal FixationNurul Falah KalokoBelum ada peringkat

- Mamiya 645 Pro Instruction ManualDokumen44 halamanMamiya 645 Pro Instruction ManualGeoff MarchantBelum ada peringkat

- RM Final PresentationDokumen25 halamanRM Final Presentationahsan puriBelum ada peringkat

- Global Colour S S 21Dokumen16 halamanGlobal Colour S S 21ssBelum ada peringkat

- Georges SeuratDokumen8 halamanGeorges Seuratapi-193496952Belum ada peringkat

- Photography Is The Process of Recording Visual Images by Capturing Light Rays On A LightDokumen10 halamanPhotography Is The Process of Recording Visual Images by Capturing Light Rays On A LightTubor AwotuboBelum ada peringkat

- Elements of Composition in PhotographyDokumen9 halamanElements of Composition in PhotographygelosanBelum ada peringkat

- Creating A RGB Composite With SAGA - Zlatko HorvatDokumen3 halamanCreating A RGB Composite With SAGA - Zlatko HorvatAshish Kr RoshanBelum ada peringkat

- Construction Site Color by NumberDokumen2 halamanConstruction Site Color by Numberangelikaroman100% (1)

- AmblyopiaDokumen56 halamanAmblyopiaenriBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Dacryocystitis Case PresentationDokumen19 halamanChronic Dacryocystitis Case Presentationr7ptzc5kcmBelum ada peringkat

- Pelayanan Primer Kesehatan InderaDokumen57 halamanPelayanan Primer Kesehatan InderaRiza ArianiBelum ada peringkat

- TelescopeDokumen3 halamanTelescopeTijani Basit AbiodunBelum ada peringkat

- OpenCV Android Programming by Example - Sample ChapterDokumen41 halamanOpenCV Android Programming by Example - Sample ChapterPackt PublishingBelum ada peringkat

- Lab ManualDokumen16 halamanLab ManualsanathBelum ada peringkat

- Cataract BookDokumen261 halamanCataract Bookstarsk777Belum ada peringkat