Fast Food For Our Preemies .3

Diunggah oleh

Edu William0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

17 tayangan2 halamanfast food

Judul Asli

Fast Food for Our Preemies .3

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inifast food

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

17 tayangan2 halamanFast Food For Our Preemies .3

Diunggah oleh

Edu Williamfast food

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 2

Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

48:397398 # 2009 by European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition

Editorial

Fast Food for Our Preemies?

Francesco Raimondi and Maria Sellitto

Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Universita` Federico II, Naples, Italy

The remarkable survival rate of increasingly smaller

infants that has been achieved in the past decades has

led to new questions for the neonatologist and the

pediatric gastroenterologist.

What should be fed to this novel population of

premature babies? How? How should we progress in

the feeding schedule? These are just a few examples that

are far from trivial if we consider the profound impact

of early nutrition on somatic growth and neurological

development in this cohort of infants (1).

We know that breast milk is better than any commercial formula and, from the neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU) point of view, it has been shown to be protective

against necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) when compared

with formula, even when breast milk is supplemented

(2,3). Intriguingly, some studies show that ones own

mothers milk offers better protection than human milk

coming from a donor bank (4,5).

Continuous feeding seems to be preferable over bolus

mode in starting the nutrition of a critical neonate according to a few studies (6,7), but mostly because of the lack

of good quality data, the issue is far from settled.

Whatever the milk (human or formulated) or the mode

of administration, physicians taking care of premature

neonates some years ago tended to postpone enteral

nutrition fearing that the early enteral route per se carried

a higher risk of NEC. This policy had to be balanced

against the prolonged use of a central venous access

with its infectious and thrombotic hazards. A popular

strategy that was then suggested was to give for some

days after birth trophic feedings (TF), that is, small

amounts of milk (eg, 0.5 or 1 mL every 2 hours) to prime

the gut and enhance its digestive and absorptive functions

(8,9). It is, however, unclear how long very low birth

weight (VLBW) infants should be kept on this minimal

regimen and, despite a large number of supporters,

concrete evidence on the benefits of TF is still to come.

The recent randomized controlled trial by Mosqueda

et al (10) concluded that TF has no advantage over

parenteral nutrition alone in growth, feeding tolerance,

mortality, hospitalization length, sepsis, and NEC. Still,

the longer the baby is on TF with a central line in place,

the higher is the risk of infection or of thromboembolic

event (10).

The speed of advancement of enteral feedings is a yet

unresolved clinical dilemma that McGuire and Bombell

(11) have tried to address in a Cochrane review collecting

data on 396 infants from 3 studies. They did not associate

unfavourable outcomes (NEC in particular) with faster

schedules, although some remarks about their analysis

must be made. Only a minority of participants in the

2 larger trials were extremely low birth weight (ELBW)

or extremely preterm infants and less than one third of the

total were fed with breast milk. The general policy

regarding the use of breast milk, a major confounder,

was left unspecified (11).

In this issue of the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Hartel et al (12) compare rapid

versus slow enteral feeding advancement in 1430 VLBW

infants recruited in 13 German level III NICUs. Taking

into account an array of short-term outcomes such as

NEC, sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy

of prematurity, weight gain, and duration of hospitalization, they conclude that slow enteral feeding is associated

with higher rates of nosocomial sepsis without a significant impact on other variables.

Although the authors should be commended for their

attempt to shed some light on a relevant and yet complicated topic of neonatal gastroenterology, there are a

few methodological caveats that the reader should bear

in mind.

This is not a prospective, randomized study but a post

hoc allocation of patients coming from a large number of

NICUs whose different protocols may help to explain the

difference (or lack of difference) between groups. It is

not a comparison between 2 clearly defined feeding

schedules; indeed, the allocation criterion was the

achievement of full enteral feeding (ie, 150 mL/kg)

Received September 6, 2008; accepted September 13, 2008.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Francesco Raimondi,

Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Universita` Federico II, Naples, Italy (e-mail: raimondi@unima.it).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

397

Copyright 2009 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

398

EDITORIAL

before (in the rapid advancement) or after (in the slow

advancement) 12.5 days of postnatal age. The choice of

such a cutoff is absolutely arbitrary.

The authors fail to provide stratification for breast milk

intake that may have influenced intestinal transit, mucosal maturation, and infection rate. The latter may have

also been affected by the higher rate of intrapartum

antibiotics used in the rapid advancement group. In the

slow advancement group, the significantly higher rates of

umbilical vein catheter placement, mechanical ventilation, and use of pressor amines may indicate the presence of sicker infants.

Rapid and successful enteral nutrition is a major milestone in the difficult and often perilous path of a VLBW

infant through the NICU. Despite these limitations, we

believe that Hartel et al gained the credit to pinpoint a key

nutritional issue that troubles the work of all neonatologists and awaits a conclusive answer.

REFERENCES

1. Dusick AM, Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Growth failure

in the preterm infant: can we catch up? Semin Perinatol 2003;

27:30210.

2. Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet 1990;336:151923.

3. Henderson G, Anthony M, McGuire W. Formula milk versus

maternal breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight

infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD002972.

4. Quigley MA, Henderson G, Anthony MY, et al. Formula milk

versus donor breastmilk for feeding preterm or low birth weightinfants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD002971.

5. Boyd CA, Quigley MA, Brocklehurst P. Donor breast milk versus

infant formula for preterm infants: systematic review and metaanalysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007;92:F16975.

6. Premji S, Chessell L. Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus

intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500

grams. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;CD001819.

7. Dsilna A, Christensson K, Alfredsson L, et al. Continuous feeding

promotes gastrointestinal tolerance and growth in very low birth

weight infants. J Pediatr 2005;147:439.

8. Berseth CL, Bisquera JA, Paje VU. Prolonging small feeding

volumes early in life decreases the incidence of necrotizing

enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2003;

111:52934.

9. Tyson JE, Kennedy KA. Trophic feedings for parenterally fed

infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;CD000504.

10. Mosqueda E, Sapiegiene L, Glynn L, et al. The early use of minimal

enteral nutrition in extremely low birth weight newborns. J Perinatol 2008;28:2649.

11. McGuire W, Bombell S. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes

to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;CD001241.

12. Hartel C, Haase B, Browning-Carmo K, et al. Does the enteral

feeding advancement effect short term outcomes in very-low-birthweight infants? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:46470.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, Vol. 48, No. 4, April 2009

Copyright 2009 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Wound International Best Practice Guidelines Non ComplexDokumen27 halamanWound International Best Practice Guidelines Non ComplexEdu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Laser Guidance Notes 101212Dokumen3 halamanLaser Guidance Notes 101212Edu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Dietary Cure For Acne by Dr. Loren Cordain The Paleo Diet The Paleo Diet™Dokumen1 halamanDietary Cure For Acne by Dr. Loren Cordain The Paleo Diet The Paleo Diet™Edu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- PICU HandbookDokumen113 halamanPICU HandbookEdu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Tanner MethodDokumen8 halamanTanner MethodEdu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Pedtext 5Dokumen716 halamanPedtext 5jay_eshwa100% (1)

- CroupDokumen13 halamanCroupEdu William100% (1)

- Japanese Encephalitis - 2011Dokumen2 halamanJapanese Encephalitis - 2011Edu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

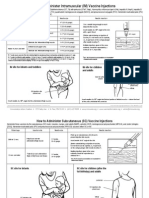

- How To Admister VaccineDokumen2 halamanHow To Admister VaccineEdu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Adenovirus Vaccine: What You Need To KnowDokumen2 halamanAdenovirus Vaccine: What You Need To KnowEdu WilliamBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Be Your Own Doctor With Acupressure - Dr. Dhiren GalaDokumen69 halamanBe Your Own Doctor With Acupressure - Dr. Dhiren GalaParag Chhaper100% (2)

- Anesthesia Drug StudyDokumen3 halamanAnesthesia Drug Studyczeremar chanBelum ada peringkat

- DLR - Tips and Tricks PDFDokumen9 halamanDLR - Tips and Tricks PDFSelda CoktasarBelum ada peringkat

- Harvard Mens Health Watch January 2021 Harvard HealthDokumen8 halamanHarvard Mens Health Watch January 2021 Harvard HealthJefferson Medinaceli MalayaoBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment and Prognosis of IgA Nephropathy - UpToDate PDFDokumen52 halamanTreatment and Prognosis of IgA Nephropathy - UpToDate PDFDerian Yamil Bustamante AngelBelum ada peringkat

- Report CapsicumDokumen105 halamanReport CapsicumRina WijayantiBelum ada peringkat

- Braddom Lower Extremity DrillsDokumen4 halamanBraddom Lower Extremity DrillsKennie RamirezBelum ada peringkat

- Geriatr Disieses PDFDokumen406 halamanGeriatr Disieses PDFYoana PanteaBelum ada peringkat

- Mwalya Wambua Final ProjectDokumen49 halamanMwalya Wambua Final ProjectWILSON MACHARIABelum ada peringkat

- Cold Chain Medication List 2021Dokumen13 halamanCold Chain Medication List 2021sumaiyakhan880Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Efficacy and Tolerability of Acetaminophen Paracetamol and Mefenamic Acid As Antipyretic in Pediatric Pati PDFDokumen7 halamanEvaluation of Efficacy and Tolerability of Acetaminophen Paracetamol and Mefenamic Acid As Antipyretic in Pediatric Pati PDFrasdiantiBelum ada peringkat

- Electronic Surgical Logbook For Orthopedic Residents AcceptanceDokumen7 halamanElectronic Surgical Logbook For Orthopedic Residents AcceptanceKhalil ur RehmanBelum ada peringkat

- Cryotech IVF Media Products and Services For Reproductive, Infertility ProfessionalsDokumen9 halamanCryotech IVF Media Products and Services For Reproductive, Infertility ProfessionalsCryoTech IndiaBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal HematuriaDokumen6 halamanJurnal HematuriaErlin IrawatiBelum ada peringkat

- Capstone OutlineDokumen3 halamanCapstone Outlineapi-395468231Belum ada peringkat

- Nutrition in Pediatrics PDFDokumen1.121 halamanNutrition in Pediatrics PDFPutri Wulan Sukmawati100% (5)

- 2022 - ACLS - Handbook 1 30 13 30 PDFDokumen18 halaman2022 - ACLS - Handbook 1 30 13 30 PDFJefferson MoraBelum ada peringkat

- S11 XylitolDokumen4 halamanS11 XylitolJholanda Ninggar BahtriaBelum ada peringkat

- Gurkeerat Singh - Textbook of Orthodontics, 2nd EditionDokumen5 halamanGurkeerat Singh - Textbook of Orthodontics, 2nd EditionndranBelum ada peringkat

- Ethnobotany and EthnopharmacologyDokumen29 halamanEthnobotany and EthnopharmacologyJohn CaretakerBelum ada peringkat

- Goljan Errata SheetDokumen11 halamanGoljan Errata SheetVishala MishraBelum ada peringkat

- End-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareDokumen5 halamanEnd-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERREROBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Tumor Biology On Cancer Treatment and Multidisciplinary Strategies - M. Molls, Et Al., (Springer, 2009) WWDokumen363 halamanThe Impact of Tumor Biology On Cancer Treatment and Multidisciplinary Strategies - M. Molls, Et Al., (Springer, 2009) WWiuliBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Stress On Academic Success in College StudentsDokumen4 halamanThe Impact of Stress On Academic Success in College StudentsSha RonBelum ada peringkat

- Sanofi-Aventis, Deepak Tripathi, ITS GhaziabadDokumen69 halamanSanofi-Aventis, Deepak Tripathi, ITS Ghaziabadmaildeepak23Belum ada peringkat

- Antibiotics Chart 1Dokumen7 halamanAntibiotics Chart 1Vee MendBelum ada peringkat

- Downward Movement - Left Hand Only: (Figure 3-7Dokumen20 halamanDownward Movement - Left Hand Only: (Figure 3-7mamun31Belum ada peringkat

- 2015 Coca-Cola MENA Scholarship ApplicationDokumen15 halaman2015 Coca-Cola MENA Scholarship ApplicationMehroze MunawarBelum ada peringkat

- Ayurveda FitoterapiaDokumen112 halamanAyurveda FitoterapiaKerol Bomfim100% (2)