1995 7 (1) SAcLJ 103 Toh

Diunggah oleh

yjw9988Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1995 7 (1) SAcLJ 103 Toh

Diunggah oleh

yjw9988Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

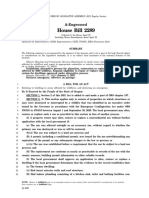

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

103

OBTAINING JURISDICTION OVER FOREIGN COMPANIES

A.

INTRODUCTION:

A recurrent problem in international commercial disputes is determining

when a foreign company1 is amenable to the jurisdiction of the local courts.

The somewhat instinctive response of chasing the foreign corporation to

its place of incorporation by effecting service out of jurisdiction under

Order 11 of the Rules of Supreme Court (hereinafter, the RSC), is often

not the most ideal solution, both in terms of convenience and tactics.2

Other jurisdictional heads which involve only service within jurisdiction3

should be considered first, whenever possible.

The purpose of this article is to explore these jurisdictional heads which

only require service within jurisdiction of the Singapore forum and consider

how they might be invoked, if at all, in the context of different physical

and economic manifestations of a foreign company within Singapore. An

early caveat is apposite, however. Scarcity of local cases, doubts as to

A foreign company is defined in the s.4 of the Companies Act (Cap. 50, 1994 Revised

Edition) as (a) a company, corporation, society, association or other body incorporated

outside Singapore; or (b) an unincorporated society, association or other body which

under the law of its place of origin may sue or be sued, or hold property in the name of

the secretary or other officer of the body or association duly appointed for that purpose

and which does not have its head office or principal place of business in Singapore. The

question of jurisdiction over foreign companies was the subject of an earlier article: see

Woon, Jurisdiction over Foreign Companies in Singapore Law [1987] 2 MLJ xxviii.

However, the whole basis of assuming civil jurisdiction was changed in 1993 owing to

amendments to s.16 of the Supreme Court Judicature Act. (Cap. 322, Singapore Statutes,

1993 Reprint of the 1985 Revised Edition.) On the effects of the amendments, see

YL Tan [1993] SJLS 557 at pp 563569. It is therefore timely to re-examine this area of

jurisdiction over foreign companies in view of these statutory changes, as well as the

caselaw which has emerged over the last few years.

For instance, service out of jurisdiction is not available as of right; a jurisdictional limb

under O.11 r.1(1), RSC must be shown and leave of court must be obtained. Burden of

proving the appropriateness of the forum according to the Spiliada [1986] 3 All ER 843

criteria rests with the plaintiff. Such service may be ignored and any resulting default

judgment may not be enforceable in another jurisdiction (at least in most Commonwealth

countries), depending on the conflict of laws rules of that jurisdiction. It is true that a

foreign company may not have assets in Singapore so that even if jurisdiction over it is

obtained by service within jurisdiction and judgment obtained, such a judgment may

have to be enforced elsewhere. However, if there have been submission or presence of

that company within jurisdiction, that may furnish a ground for enforcement before

another court in the Commonwealth, although ultimately, everything depends on the

enforcement rules of that jurisdiction. If the foreign company has a local debtor, then

garnishee proceedings might be commenced after obtaining the local judgment.

This expression, within jurisdiction will be used interchangeably with the expression, in

the forum. Needless to say, forum refers to the country before whose courts the action

is brought.

104

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

applicability of cases from other jurisdictions, absence of judicial survey of

the entire field and recent statutory amendments in 1993 make the task of

constructing a conceptual framework in this area difficult and the analysis

to be put forward presently, tentative.

B.

THE STATUTORY REGIMES

The starting point is s.16(1) of the Supreme Court Judicature Act4 which

sets out the scheme of civil jurisdiction of the High Court of Singapore for

in personam actions. In fact, s.16(1) supplies two of the three statutory

regimes in relation to jurisdiction over foreign companies. Under s.16(1)(i),

the High Court has jurisdiction to hear an action in personam where the

defendant is served with a writ or other originating process in Singapore

in the manner prescribed by the Rules of Court. S.16(1)(b) confers the

High Court with jurisdiction if the defendant submits to the jurisdiction of

the High Court.

In addition, s.16(3) provides that without prejudice to the generality of

subsection 1 the High Court should have jurisdiction as is vested in it by

any other written law.5 S.16(3) thus captures any other jurisdiction conferring

statutory provisions, which in relation to foreign companies in Singapore,

would presently be argued to include Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies

Act.

C. DIVISION II, PART XI OF THE COMPANIES ACT

Whilsts.16(1) of the SCJA sets out the heads of civil jurisdiction in

Singapore, it may be more convenient to begin with this third statutory

regimeunder the Companies Act rather than the two contained in s.16(1).

If, as presently argued that it would, certain provisions of this Part of the

Act do indeed confer jurisdiction, then any foreign company that is

registered under s.368 of this Part could be served in accordance with the

procedure prescribed in s. 376 and be made amenable to jurisdiction of the

Singapore courts. There would be no further need to consider if the other

two jurisdictional limbs in s.16(1) could be invokedwhich,subject to one

exception,6 remain possible (though in many situations, less attractive)

alternatives.

4

5

Supra, note 1.

Written law according to s.2(1) of the Interpretation Act (Cap.1, Singapore Statutes,

1985 Rev. Ed.) includes, inter alia, all Acts, Ordinances and enactments by whatever

name called.

That of service under s.16(1)(a)(i) read with O.62 r.4. Infra, Part D of this article.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

105

(i) Relevant Provisions of Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act.7

Under Division 2, a foreign company which wishes to commence to carry

on business or establish a place of business8 in Singapore must be registered

under s.368. Registration of such a foreign company requires the lodgment

with the Registrar of Companies of, inter alia, the names and addresses of

two or more natural persons resident in Singapore who are authorised to

accept on its behalf service of process9 (such persons being referred to as

agents10 of the foreign company). In addition, such a foreign company

must have a registered office in Singapore11 and notice of the situation of

this office in Singapore must also be lodged.12 Failure to register before

carrying on business or establishing a place of business attracts an offence

(penalised by a fine) under s.386.

Any documents (including any originating processes) required to be served

on a foreign company may be left at or sent by post to

a. the registered office of the foreign company (if addressed to the

foreign company) or

b. the registered address of any of its agents (if addressed to its

agent) or

c. the registered office of the foreign companys place of incorporation if it has ceased to maintain a place of business in Singapore.13

In essence then, a foreign company which wishes to carry on business or

establish a place or business in Singapore must register itself, supplying the

names of its local agents as well as the address of its registered Singapore

office and once so registered, may be served with process in the manner

prescribed by s.376. It is significant to observe that if a foreign company

carries on business or establishes a place of business in Singapore but fails

to register itself, the service procedure set out in s.376 does not apply.

As a matter of historical interest, this problem was addressed by s.305 of

the Companies Ordinance of 1955 which allowed service on a place of

business established by the unregistered foreign company. But this provision

7 It appears that Part XI, Division 2, in its present form was introduced in 1967, via the

Singapore Companies Act of 1967 (Act 42 of 1967). The provisions relevant to the

present analysis, ss.329, 330, 332 and 339 of the 1967 Act are similar to ss.365, 366, 368

and 376 of the current Act. Prior to 1965, the provisions which dealt with registration and

service of foreign companies were in pari materia to those found in the various English

companies legislations. Infra, note 32. See for instance, ss.300, 301 and 305 of the

Companies Ordinance, 1955 and prior to that, s.290 of the Straits Settlements Companies

Ordinance of 1923 and s.287 of the Straits Settlements Companies Ordinance of 1915.

8 The meanings of these two phrases will be considered presently.

9 s. 368(1)(e), Companies Act.

10 s. 366(1), Companies Act.

11 s. 370(1), Companies Act.

12 s. 368(1)(f), Companies Act.

13 s. 376(a)(c), Companies Act.

106

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

and others dealing with registration and service in the 1955 Ordinance

(which were probably borrowed from the English Companies Act of 1948)

were left out of Companies Act of 1967 which repealed the 1955 Ordinance

and also introduced the present Part XI, Division 2 provisions.

(ii) Legislations Comparable to Division 2 of Part XI, Companies Act.

The provisions in Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act which are

relevant to our discussion have close parallels in Australia, Malaysia and

England. For instance, s.343 of Part 4.1 Division 2 of the Australian

Corporations Law, 1989 forbids a foreign company to carry on business14

before it is registered under provisions in Part 4.1, Division 2. The ambit

of the expression, carrying on business, found in s.21(2),(3) of the same

Act is similar to that found in s.366 of our Companies Act. Similarly, a

local agent must be appointed by the foreign company and the company

must have a registered office.15 Service procedure under s.363 is broadly

similar to s.376.16

The Malaysian provisions are in pari materia similar to those in Singapore,

albeit numbered differently.17

The provisions18 in England contained in Part XXIII of the 1985 Companies

Act are different from Part XI, Division 219 in several pertinent aspects

although the basic schema remains the same. S. 691(1) of the English

Companies Act 1985 requires a foreign company to register within one

month after establishing a place of business20 and to lodge for registration,

inter alia, the names and addresses of one or more persons authorised to

14 But s.343 of the Corporation Laws leaves out the expression, place of business which

appears in Part XI, Division 2. This is perhaps because the two expressions, place of

business and carrying on business are synonymous: see s.21(1). The relevant provisions

of two earlier companies legislation in Australia, the 1981 Australian Companies Code

and the 1961 Companies Act are in pari materia with those in Part XI Division 2. See,

for instance, ss.510, 512, 518 and 530 of the 1981 Code.

15 See ss.344 and 345 of the Corporations Law, 1989. See also s.363 on the ways service can

be effected.

16 The main differences seem to be that there is no equivalent to s.376(c) in s.363 of the

1989 Corporations Law (the provision that deals with service on registered foreign

company) and s.363(3) permits service on locally resident directors. These two differences

are found in s.530 of the 1981 Code as well.

17 See the Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act of 1965, Malaysia; in particular ss.329,

330, 332, 333 and 339.

18 Not taking into account the provisions introduced by virtue of the Eleventh Company

Law Directive under European Community regime.

19 See the remarks of Chao Hick Tin J in the Court of Appeal decision of Bank of Central

Asia v Rosenberg [1995] 1 SLR 490. The first instance decision is reported in [1994] 1

SLR 798.

20 Unlike the Singapore provisions, there is no reference to carrying on business in the

English provisions.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

107

accept service. Service on the foreign company may be effected on such an

agent of the company by addressing the process to him and leaving the

process at or posting it to the agents registered address.21 It will be noticed

that no mention is made in the English provisions of a company carrying

on business and service on a registered company may only be effected on

the agent. Perhaps more significantly, there is a UK provision which, since

1967, has no local equivalent: if the foreign company fails to register, then

service may still be effected at a place of business established by the

company in the England.22 As will presently be discussed, this lacuna in the

local legislation presents problems on both jurisdiction and service.

(iii) Does Division 2 of Part XI confer jurisdiction?

This question does not admit of an easy reply. However, what appears to

be an affirmative answer may be obtained from a number of indirect sources.

The legislative purpose behind the registration and service provisions of

this Division, particularly ss. 365, 366, 368 and 376 seems predominantly to

be one of protection of local creditors of the foreign company by securing

for them a procedure for service which does not involve service out of

jurisdiction. This obviates the inconvenience of service out and puts the

potential plaintiff at no worse a position than he would be if he were to sue

a local company. This purpose was identified by Ackner LJ (as he then

was) in South India Shipping Corporation v Export-Import Bank of Korea23 ,

by Winslow J in Goh Siew Wah v Columbia Films of Malaysia24 and has

been echoed in two Australian decisions, Maronis Holdings Ltd v Nippon

Credit Australia Ltd25 as well as Gillett v The National Benefit Life and

Property Assurance Company Ltd.26 Another justification, somewhat less

sophisticated, stems from some notions of mutuality: a foreign company

can sue any local creditor as if it is a local plaintiff 27 and so should be

capable of being sued as if it were a local defendant.

Admittedly, these judicial pronouncements do not bear directly on the

jurisdiction question and that there is no express provision in any Part XI,

Division 2 or other comparative legislation which deals specifically with

21 S.695, English Companies Act 1985.

22 S.695(2), English Companies Act, 1985.

23 [1985] 2 All ER 219 at p.224. See also the judgment of Lord Sumner in Employers

Liability Assurance Corporation v Sedgwick, Collins and Company [1927] AC 95 at p.108

24 [1966] 1 MLJ 39 at pp.4041. His Honour said that the object of s.305 (a predecessor of

s.376) is to provide a method of service on a company incorporated abroad which carries

on business locally...its justification is convenience to the public. See also United Kingdom

Tobacco v Malayan Tobacco Distributors [1933] MLJ 1 where it was said that the provisions

have the salutary effect of controlling the activities of foreign companies within jurisdiction.

25 [1990] 2 ASCR 136 at p.140, a decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

26 (1918) 24 CLR 374 at 378, a decision of the High Court of Australia.

27 As far as jurisdictional requirements are concerned. Needless to say, it may be asked to

put up security for cost.

108

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

jurisdiction. However, it should be noted that as far as English and

Australian cases are concerned, they are to be read with the common law

conflict of laws principle in mind, that the foundation of jurisdiction in

personam is service of the writ on a defendant present within jurisdiction.28

It may therefore be argued that by providing for a statutory substitute for

the common law equivalent criterion of corporate presence in the form of

registration and a special facility for service on foreign companies registered

within jurisdiction, the legislatures of these countries have already created

an avenue by which jurisdiction over foreign companies may be exerted.

Any express enactment on denoting that service in the forum confers

jurisdiction would be superfluous.29

Indeed, such an argument, reading into statutory provisions dealing with

foreign companies a jurisdictional nexus is supported by writers and cases

on the area. Both Dicey and Morris and Cheshire and North regard service

under the relevant UK provisions on foreign companies as conferring

jurisdiction. The editors of Cheshire and North, citing as support the decision

of the Theodohos,30 make this point aptly:

... the basis for taking jurisdiction against foreign companies following

service of a writ within the jurisdiction is to be found in the provisions

of the Companies Act,...31

While, the English provisions on which the above observations are based

are somewhat different from those of Singapore in that they include service

provisions against errant, unregistered foreign companies, the principle

that service on registered companies confers jurisdiction has always been

maintained, even at a time when the English provisions contained the

same lacuna as the local provisions.32 In Employers Liability Assurance

28 See Dicey and Morris, Conflict of Laws, 12th edition, Volume 1 at p.298; Cheshire and

North, 12th edition, at p.182.

29 The argument can be taken one step further. A Singapore incorporated company may be

served in the way described in s.387. The lack of any express conferment of jurisdiction

in s.387 bothers no one. Such a company is assumed to be present by virtue of its local

incorporation. (See Dicey and Morris, supra note 28 at p.305; Dicey and Morris remark

seems to equate corporate domicil which is a function of incorporation with corporate

presence). As aforesaid in the text, the aim of requiring registration of a foreign company

is after all to put it in the same position as a local company, as regards convenience of

starting a suit against it.

30 [1977] 2 Lloyds Rep 428.

31 Cheshire and North, supra, note 28 at p.186.

32 It may be useful at this juncture to briefly state the legislative history of the English

provisions. Before the Companies Act 1907 was enacted, there was no statutory provision

dealing with service of foreign companies and so recourse was had to O.9 r.8 of the RSC

of 1883. S.35 of the Companies Act of 1907 changed this by introducing registration of

foreign companies and a service procedure on such registered foreign companies. This

provision was repealed and re-enacted in s.274 of the Companies (Consolidation) Act,

1908 which was in turn repealed by the Companies Act 1929 and replaced by ss.346(3)

and 349. Until the Companies Act of 1929, there was no provision dealing with service

of unregistered companies; therefore, England had the same statutory lacuna as that

presently prevailing in Singapore. However, s.349 closed up the lacuna by the introduction

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

109

Corporation Limited v Sedgwick, Collins and Company Limited33 , Lords

Sumner and Parmoor opined that the act of registration amounted to a

submission to the territorial jurisdiction of the English courts.34 Lord

Parmoor, additionally, appeared to accept that registration upon establishment of a place of business created some kind of territorial presence which

is the statutory equivalent of corporate presence under common law in

that it, too, renders the foreign company amenable to jurisdiction and

service.35 Submission to jurisdiction based on registration is admittedly

artificial36 , since registration on pain of a fine37 hardly connotes any

voluntariness which underlies any submission to jurisdiction and in any

event, any such submission is probably implied, a notion which has been

largely rejected in English and local cases.38 Registration as a statutory

parallel to common law corporate presence within jurisdiction is somewhat

more attractive and seems to have the support of Dicey and Morris39

although it would be inconsistent with cases which decided that cessation

of business at the time of service did not render the service bad.40

The Australian conflict of laws writers, Sykes and Pryles, also reject

submission.41 The learned writers adopt the position that the act of

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

of service on a place of business established by an unregistered foreign company. These

provisions in the 1929 Act were repealed by the Companies Act 1948 and re-enacted as

ss. 407, 409, and 412 (The Theodohos, supra, being decided on these provisions). The

1948 provisions became ss.691and 695 of the English Companies Act of 1985.

Supra, note 23.

This notion of submission to jurisdiction based on registration was subsequently followed

in Sabatier v The Trading Company [1927] 1 Ch 495 and The Madrid [1937] P 42. See

also Nygh, Conflict of Laws in Australia, 5th Edition (1991) at p. 501 which takes the

same view.

See Part D of this article.

See Dicey and Morris, supra, note 28 at p.313. See also, Sykes and Pryles, Australian

Private International Law, Conflict of Laws, 2nd Edition, (1987) at pp.2728. This view

is omitted in the 3rd Edition (1991) of the book although the position that the companies

legislations confer jurisdiction is still retained. See pp. 2526 of the 3rd Edition.

Failure to register a foreign company attracts a fine of maximum $1000 under s. 386 of

the Companies Act in addition to a default penalty under s.408.

See Vogel v Kohnstamm Ltd [1973] QB 133, Sunline v Cantopex, [1986] 2 MLJ 348; UOB

v Tjuk Tjio Nyuk [1987] 2 MLJ 295.

Supra, note 28, at p.313.

It is hardly surprising to note these cases, like Sedgwick & Collins, supra, note 23 and

Sabatier, supra, note 34 are those that espouse the submission by registration theory.

Supra, note 36. Cf Kelty v Athertons (SA) Pte Ltd, (1982) 6 ACLR 477, a decision of

Sangster J of the Supreme Court of South Australia. The Court in this case seemed to

rely on the common law requirement of corporate presence (or residence) as the source

of jurisdiction over foreign companies and did not see the need for reliance on the South

Australian Companies Act provisions which relate to registration and service. The court

went on to observe that these provisions do not bring a registered foreign company into

a different position in relation to jurisdiction of the South Australian courts than an

unregistered foreign company. This observation is, with respect, aberrant as it runs counter

to the view taken by cases and academic writers, including the Australian conflicts writers,

cited above. Further, the remarks are probably dicta since the judge considered the issue

on his own accord without either counsel challenging the courts jurisdiction and in any

event, jurisdiction was in fact obtained by submission through unconditional appearance.

110

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

registration confers jurisdiction under the legislation and thus no recourse

need be had to jurisdiction derived from either submission or carrying on

business in the forum. The Australian perspective is particularly relevant

given the greater local resemblance between their provisions and ours, a

fact which is not altogether surprising, since a fair number of provisions in

our Part XI, Division 2 bear Australian roots.

In view of these judicial and academic authorities, it seems difficult to

argue that Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act is not jurisdiction

conferring. Whether the conceptual basis of jurisdiction conferment is

submission, corporate presence or registration per se, is perhaps not as

important as the fact that the provisions actually create a source of

jurisdiction.

In any event, whatever might have been the position before, the 1993

amendments to s.16 of the Supreme Court Judicature Act, for two reasons,

the new provisions of s.16(1) do compel the conclusion that Part XI, Division

2 is jurisdiction conferring. The first reason is this. S.16(1)(a)(i) provides

that jurisdiction is based on service according to the rules of court. If

service is effected under s.376 of the Companies Act, such service is not in

accordance with the RSC and so falls outside the purview of s.16(1)(a)(i).

One might then ask rhetorically what is the effect of service under s.376.

If it is solely to give notice of suit to the foreign corporate defendant, must

jurisdiction nevertheless be made available through compliance with

s.16(1)(a)(i)? This would necessitateduplication of service. Furthermore,

in the absence of submission to jurisdiction by the defendant, the avenue

for such service is very restricted. O.62 r.442 cannot be employed as it

applies only in the absence of provisions made in any other enactment, like

s.376. O.10 r.2, which is the other alternative, can only be invoked if its

special criteria are fulfilled.43 It should also be noted that the Legislature

does not intend s.16(1) to as operate to the exclusion of all other statutory

sources of jurisdiction, including that found in the Companies Act. S.16(3)

makes this quite apparent.

Secondly, with the amendment to s.16(1) making jurisdiction dependent

on service within or out of jurisdiction, the conceptual premise of in

personam jurisdiction in Singapore, even though cloaked in a statutory

outfit, now resembles that of common law.44 That being the case, the

arguments about the superfluity of a specific jurisdiction provision along

with a service provision in the company legislations of Australia and England

would apply with full effect in Singapore as well.

42 See Part E of this article.

43 Ibid.

44 See the remarks of the Minister of Law in parliamentary debates to the amendment of

s.16 reproduced on p. 20. Parliamentary debates are relevant to the construction of

statutes; see s.9A of the Interpretation Act (Cap 1, Singapore Statutes, 1985 Rev Edition)

as well as the decisions of Pepper v Hart [1992] 3 WLR 1032 and Raffles City v Attorney

General [1993] 2 SLR 580.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

111

(iv) Meaning of place of business and carrying on business

The analysis thus far is registration of a foreign company is necessary

before it establishes a place of business or commences to carry on business45

and when so registered, it becomes subject to the service and jurisdictional

regime of the Companies Act. Since either establishing a place of business

or carrying on business triggers off certain jurisdictional consequences, it

is essential to ascertain what kinds of corporate acts amount to either

activity.

(a) Place of Business

Beginning with place of business, this expression is not defined in Part

XI, Division 2. However, there are two sources of jurisprudence which

may be tapped in determining the parameters of this phrase. The first

would be common law cases on what is meant by a company carrying on

business ie corporate presence.46 The second would be cases from

jurisdictions which have considered this phrase in comparable legislations.47

The common law cases on carrying on business will be considered in detail

presently; suffice, however, that the main principles distilled from these

cases be stated for present purposes. A companys place of business refers

to a local habitation of its own;48 it is where the company carries out

business for a definite period of time. There must be a degree of fixity or

permanence about the place where business is conducted (although a booth

in an exhibition lasting 9 days has been held to be sufficient)49 ; tenure of

the place in the form of lease or title though not essential, is a strong

indicium.50 If business of the company is carried out by an agent, there

would be compelling evidence of corporate presence if the agent has the

authority to enter into transactions binding on the foreign company51

although other aspects of the relationship are also relevant.52

45 See ss.365 and 368 of Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act.

46 See Dicey and Morris, supra, note 28 at p.306 and Cheshire and North, supra, note 28,

11th Edition at pp.189191. See also, The Theodohos, supra, note 30, The Vrontados

[1982] 2 Lloyds Rep 428 and South India Shipping Corporation v Export-Import Bank

of Korea , supra, note 23.

47 It is true that the Singapore Court of Appeal in the Rosenberg decision cautioned against

indiscriminate adoption of English cases on place of business and pointed out the relevant

provisions of the Singapore and UK company legislation are materially different. See

page 15 of the judgment. However, this caution was made in the context of construction

of O.10 r.2 of the RSC, rather than Division 2 Part XI of the Companies Act. However,

it should be noted that in the UK provisions, the only jurisdictional trigger is establishing

a place of business; carrying on business is absent.

48 Lord Advocate v Huron & Erie Loan and Savings Co. [1911] SC, 615.

49 Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v A G Cudell & Co [1902] 1 KB 342.

50 La Bourgogne [1899] P 1, affirmed on appeal to the House of Lords, [1999] AC 431.

51 Okura & Co v Forsbecka Jernverks Aktiebolag [1914] 1 KB 715.

52 Adams v Cape Industries [1990] Ch 433.

112

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

These common law principles are not to be regarded as rigid requirements.

Indeed, as some decisions which construed comparable English legislations

show, the expression,place of business in Part XI seems to encompass but

is not confined to its common law meaning. In this connection, a trilogy of

English decisions are illuminating.

The first is South India Shipping Corporation v Export-Import Bank of

Korea,53 in which the defendant bank was held to have established a place

of business for the purpose of the proviso to s.412 of the English Companies

Act of 194854 even though its branch office in London did not conclude any

banking transactions but merely conducted activities incidental to its banking

business, such as the collection and dissemination of information,

maintenance of public relations with other banking and financial institutions

in the United Kingdom, as well as conduct of other liaison activities. The

Defendants took up a lease of the premises and employed staff to carry

out its activities. On these facts, Ackner LJ found that the defendant bank

had established a place of business in England. His Lordship saw no need

for the activities carried out within jurisdiction to be the substantial or

paramount part of the defendants business; such activities could be

incidental to the main objects of the company, as those in this case were.

As Parliament has not place any express qualifications or limitations on

the words a place of business, the court did not see fit to imply any.

The second case in the trilogy, Re Oriel Ltd, did not arise in a jurisdictional

context.55 It is nonetheless useful in that it reads into the same expression,

establish a place of business,56 a degree of permanence and corporate

identifiability in the premises taken up by the foreign company. To begin

with, Oliver LJ did not think that there is complete symmetry in the concepts

of carrying on business and establishing a place of business. A company

sending its agents over to meet clients in a hotel lounge may be carrying

on business there but does not establish the hotel lounge as a place of

business. His Lordship went on to expound on the meaning of the expression,

...when the word established is used adjectively, ..., it connotes not

only the setting up of a place of business at a specific location, but a

degree of permanence or recognisability as being a location of the

companys business. The concept, as it seems to me, is of some more

or less permanent location, not necessarily owned or even leased by

53 Supra, note 23.

54 The proviso to s.412 of the 1948 Companies Act dealt with service on unregistered

companies. As note 32 makes it clear, this was the predecessor to s.695(2) of the Companies

Act of 1985.

55 [1985] 3 All ER 216. The case actually involved registration of a charge created by a

foreign company over English property.

56 Which also appeared in s.106 of the English Companies Act of 1948.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

113

the company, but at least associated with the company and from

which habitually or with some degree of regularity business is

conducted.57

So, in this case, a foreign company which acquired and mortgaged several

petroleum garage sites as well as entered into petroleum supply agreements

with the mortgagee, was held not to have by these acts alone established

a place of business on any of the sites it acquired. The private residence

within jurisdiction of the directors per se did not amount to a place of

business either, although it might be if it is the seat of corporate direction

and control from which business correspondence emanates. Physical

indication of the company such as a signboard or brass plate is not necessary

though its absence is a factor to be taken into account.58

Cleveland Museum of Art v Capricorn Art International,59 the third English

decision on the issue, illustrates how far the courts have gone in stretching

the notion of place of business. A disused church converted into a storage

and viewing place of substantial pieces of artwork belonging to an artdealing foreign company was found by Hirst J to constitute the latters

place of business, storage and viewing being important activities of the artdealing business. There was no evidence that art pieces were sold and

purchased at this place, or of external signs of corporate identity (though

perhaps understandable on the facts); nor indeed did the foreign company

have exclusive use of the place. Perhaps influenced by the tenuous evidence

supporting jurisdiction (although this was not expressed, there being the

firmer ground of lis alibi pendens to stand on), the court was prepared to

stay the action on forum non conveniens.

Several trends emerge from this trilogy of cases. First, all the judges in

these three cases seemed to approach the matter as a question of fact and

did not adhere rigidly to the common law requirements outlined above, in

particular, the ability of the branch or agent to contract on the foreign

companys behalf. Instead, decisions are arrived at largely a matter of

scrutiny on the kind of corporate activities pursued in the forum. In other

words, establishment of a place of business is a question of fact which

depends on the circumstances of the individual case. Secondly, as South

India Shipping and Cleveland Museum demonstrate, incidental or facilitative

activities, which are not directly capital generating, may be sufficient to

constitute a place of business, depending on the nature of the business as

57 At p. 220 of the judgment. Cf Re Tovarishestvo Manufactur [1944] 1 Ch 404 in a company

whose directors conducted business from the same hotel each of a number of years was

held to have a place of business there for the purposes of winding up.

58 On this point, see also Deverall v Grant Advertising Inc. [1955] 1 Ch 111.

59 [1990] BCLC 546. See also the extreme decision of Sabatier v The Trading Company,

supra, note 34 in which a registered foreign company which had ceased to carry on

business within jurisdiction was held to continue maintaining its place of business even

though all that was done there were certain administrative activities like remittance of

dividends to shareholders. It is however not entirely clear from the judgment how the

conclusion was arrived at.

114

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

well as the extent and continuity of such activities. Thirdly, neither the

physical premises on which the business is located, nor the tenure (if any)

which the company holds on it seems to matter very much. A commercial

setting, say an office, is not essential so long as the place (which could even

double as a residence) is and has for some time been identified with the

foreign company.

Finally, as the expression, place of business received a wide construction

in the cases, there is a corresponding expansion in the scope of jurisdiction

under the English Companies Act and thence, if we adopt the approach in

these cases, in our Companies Act as well. What this means in practical

terms is that even tangential economic activities in a fixed place may be no

safeguard for a foreign company against the necessity of registration and

being ensnared into the web of jurisdiction if such manifestations amount

to the establishment of a place of business. As it appears to be a question

of degree, depending on the kind, frequency and volume of corporate

activities conducted within jurisdiction, measures to forestall jurisdiction

might not have their expected effects, if indeed they are commercially

practicable. This may be a matter of some concern for a commercial (and

regional) hub like Singapore that foreign companies desiring to carry out

anything but the slightest activities may have to register and be exposed to

suits which may have nothing to do with the activities here, especially from

parties or their advisers attuned to the practice of forum-shopping. The

more extensive this jurisdictional web, the most pressing is the need to stay

actions for which Singapore is not appropriate forum,60 especially those

that smack of forum-shopping.

(b) Carrying on Business

This expression is partly defined in s. 366(1) as including establishing or

using a share transfer or share registration office or otherwise dealing with

property situated in Singapore as an agent, legal personal representative,

or trustee, whether by employees or agents or otherwise.... As this definition

is not exhaustive61 , s.366(1) does not set out all the parameters of the

expression although, s.366(2) does enumerate a number of activities which

do not amount to the company carrying on business in Singapore. These

exceptions consist of the company becoming a party to any action or

60 The Spiliada, supra, note 2 which has been locally accepted: see, for instance, Brinkerhoff

Maritime Drilling v PT Airfast Services [1992] 2 SLR 776; Eng Liat Kiang v Eng Bak

Hem [1995] 1 SLR 577.

61 Since it uses the word, includes. See also Luckin v Highway Motel (Carnarvon) Pty Ltd

(1975) 133 CLR 164 at p.178. For instance, as Gibbs J pointed out in Luckins case, if

a defendant company dealt with property for itself and not as an agent (and therefore

not coming within the partial definition of the equivalent of our s.366(1)), it would still

be carrying on business provided its dealings were not isolated transactions.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

115

arbitration proceedings, holding meeting for its directors or shareholders,

maintaining a bank account, effecting any sale through an independent

contractor, soliciting any order which has to be accepted outside Singapore,

creating a charge over property, securing or collecting a debt or enforcing

security relating to such debt,62 conducting an isolated transaction not

repeated from time to time and investing funds or holding property.

It is difficult to discern any unifying principle that threads through these

motley collections of exceptions. They can broadly be divided into two

kinds: those that reflect common law principles and others which appear

to be a collection of some common corporate acts. Coming within the

former category would be the exceptions relating to soliciting for orders

which are transmitted for acceptance outside Singapore63 and carrying out

isolated transactions.64 The effect of sale through an independent contractor

is, on plain reading, wide for an agent paid by commission may conceivably

be an independent contractor, yet such a factor per se does not preclude

the company from carrying on business at common law. A sensibly narrower

reading, by confining this exception to situations of resale through a third

party, would render it more resonant with common law principles.

Aside from the statutory parameters laid out in s.366(1) and s.366(2), it is

still necessary to ascertain what other activities might conceivably come

within the expression, carrying on business. There appear not to be any

direct local authorities on the point, but two lines of cases are worth

exploring. The first consists of cases borrowed from jurisdictions with

comparable legislations, particularly Australia. The clearest guidelines as

to what carrying on business entails come from the Australian High Court

decision of Luckin v Highway Motel (Carnarvon) Pty Ltd65 , in particular

the judgment of Gibbs J (as he then was).

Although this case, like Re Oriel, involves registration of charges created

by a foreign company, the provision construed is in fact the Australian

equivalent of our s.366(1) and so to that extent, relevant to the present

analysis. The foreign corporate defendant was a tour agency whose overland

tour buses over a period of a year travelled through Western Australia

(where it had neither an agent, a place of business or any property). The

62 On this exception, see also Koh Kim Chai v Asia Commercial Banking Corporation

[1981] 1 MLJ 196 which decided that for the purposes of the Banking Act of Malaysia,

taking steps to enforce a charge created over land within jurisdiction does not amount

to carrying on business there.

63 See, for instance, the common law cases of Okura v Forsbecka , supra, note 51 and Vogel

v Kohnstamm, supra, note 38.

64 At common law, business must be carried out within jurisdiction for a definite period of

time: SaccharinCorporation v Chemische Fabrik von Hedyon v Saccharin Corporation

[1911] 2 KB 516 though nine days of business at a particular place has been held to be

enough: Dunlop v Cudell, supra, note 49.

65 Supra, note 61.

116

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

defendant agreed to provide its tourists with food and either accommodation

or camping sites while they were in Western Australia which arrangement

necessitating the buying of food and hiring of accommodation from various

parties in Western Australia.

Such commercial transactions entered into in Western Australia was held

to amount to carrying on business there. It should be noted that the

commercial transactions in nature were more of a facilitative or incidental

nature, but like cases construing the expression, place of business, that

fact did not seem to influence the decision. Gibbs J opined that the carrying

on business connotes ...at least, the doing of a succession of acts designed

to advance some enterprise of the company pursued with a view to pecuniary

gain.66 This emphasis on a succession of acts echoes the natural meaning

of carrying on. It is also consistent with the exception in s.366(2)(h) based

on isolated transactions as well as earlier Australian authorities.67

As is evident from Luckin itself, the carrying on business does not have to

be conducted through a place of business within jurisdiction,68 a point

borne out by the disjunctive language used in s.365 itself. Neither is there

need for corporate residence (in the sense of the place where central

management and control emanates)69 within jurisdiction. The way business

is conducted can even be rather transitory, like the transactions in Luckins

which were entered into as and when the tour buses travelled through

Australia, though of course, it can take the more usual form of a local

agent, as Re Norfolk Island Shipping Line Pty Ltd,70 another Australian

decision on the equivalent of s.365, illustrates.

In the final analysis, the task at hand is an application of these principles

to the facts of the case, but in some instances, this factual enquiry have

surprisingly liberal results. For instance, in Re Atlantic Isle Shipping Co

Inc,71 a decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, the only

evidence of any trading within jurisdiction was the foreign companys only

66 Supra, note 61 at p.178. This principle was applied in Re Norfolk Island Shipping Line

Pty Ltd (1988) 6 ACLC 990, a decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

67 See Lamson Store Service v Weidenbach (1904) 7 WAR 166 (a single transaction within

jurisdiction is insufficient) and Colley v Mead (1917) 20 WAR 1.

68 To the extent that no place of business is needed, Oibbs Js construction of carrying on

business may even be somewhat broader than the common law understanding of the

phrase. See Part D of this article for discussion of common law cases on the area.

69 Which is the common law meaning of corporate residence: see de Beers Consolidated

Mines v Howe [1906] AC 455. See, however, Lorraine Osman v Elders Finance Asia Ltd

[1992] 1 SLR 369, cases on corporate residence which arose in a jurisdictional context

should not be used in the context of a moneylending statute. The court did not say that

cases on corporate residence which arose in other contexts should not be used in a case

which involves jurisdiction.

70 Supra, note 66. See also, Gillett v The National Benefit Life and Property Assurance

Company Ltd, supra, note 26.

71 (1988) 6 ACLC 992

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

117

vessel performing some loading operations in New South Wales from time

to time coupled with a bank account there. This meagre evidence notwithstanding, the court found sufficient material to suggest that the company

was carrying on business there. But however varied the requirement as to

the requisite degree of trading may be, there must actually be some trading;

acts preparatory to that are not adequate.72

Apart from this line of cases which interpret comparable provisions, the

line of common law cases on corporate presence may also cast some light

on the ambit of the expression, carrying on business in s.366. These cases

will be dealt with in Part III of this article. Suffice that we now examine

what claims they have to relevancy. First, given the presence of an inclusive

definition of carrying on business in s.366, a restrictive construction which

excludes the common law principles would be odd. Secondly, the exceptions

in s.366(2) which reflect common law principles bear out the inference that

s.366 was drafted with the common law in mind, even though there might

have been an intention to extend beyond it. Thirdly, the cases that construed

provisions which are the equivalent of s.366 referred to common law cases

as well, suggesting again s.366 was not meant to stand on its own.

(v) Service on Registered Foreign Company and Various Problematic

Situations arising therefrom.

As aforesaid, under s.376, a registered foreign company may be served

with process sent by post to or left at (if addressed to him) the registered

address of one of its agents73 or (if addressed to the company) its registered

office or if the company has ceased to maintain a place of business in

Singapore, at the registered office in the companys place of incorporation.

A foreign company that fails to register although it is required to cannot

be served according to the procedure in s.376 since there would not be any

registered addresses either of its office in Singapore or of its agents. Other

provisions for service would have to be resorted to.74

Nothing in s.376 suggests that service under s.376 is confined to actions

based on causes of action which arose in Singapore or out of the foreign

companys operations in Singapore.75 There is also nothing in Part XI,

Division 2 or indeed, s.376 which confines service on a registered foreign

company to the above procedure. Thus, if service is effected under, say,

O.10 r.1(2) or O.10 r.1(3) of the RSC, the procedure in s.376 need not be

72 Colley v Mead, supra note 67.

73 See Goh Slew Wah v Columbia Films of Malaysia Ltd, supra, note 24, a decision of the

High Court of Singapore in which a challenge was unsuccessfully mounted on the form

of address on the writ.

74 See Part D of this Article.

75 See South India Shippings case, supra note 23, for instance. See also Dicey and Morris,

supra, note 28 at p.308. Cf Service under O.10 r.2, RSC.

118

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

followed.76 Similar reasoning applies to service under O.10 r.2.77 However,

O.62 r.4 of the RSC which permits service on various officers of the

registered company cannot be used in lieu of s.376 since the former provision

only applies in cases for which provision is not otherwise made by any

written law, and written law would of course include a statutory provision

like s.376 of the Companies Act.78

S.376, by itself, seems clear enough but there can still be situations in

which service under s.376 might be problematic. What follows is a discussion

of some such situations.

(i)

Irregularity of Service

In at least one local decision, P T Pelajaran Nasional Indonesia v Joo

Seang & Co Ltd,79 a strict view was taken on the need for strict compliance

in service of process on companies. The case actually involved irregularity

of service on a local company80 (the writ being wrongly addressed though

the defendants director appeared to have notice of it) for which the plaintiff

was entirely blameless. It is conceivable that this emphasis on strict

compliance with a prescribed procedure for service might extend to s.376,

although in this regard, clear authorities are absent.

However, contrary to what Joo Seangs case decided, what scant authority

there is does suggest a certain degree of tolerance. In Goh Siew Wah v

Columbia Film of Malaysia,81 the writ was sent to the address of a registered

foreign companys agent (being then the only method of service) but

inadvertently addressed to the company instead of the agent which was

what the legislation required. Service, as may be recalled, was eventually

effected in another manner, according to O.10 r.1(2) but Winslow J seemed

prepared to hold, obiter, that the writ itself was correctly addressed for

the purpose of the Companies Act provisions notwithstanding the slight

violation of the service provision. Contrariwise, if the irregularity is use of

an entirely erroneous service provision, there is some authority for saying

that service should be set aside.82

76 See Goh Siew Wahs case, supra note 24 in which the act of the solicitor for the foreign

company in accepting service under O.10 r.1(2) on behalf of his clients was held to be

effective service. Winslow J said that the service under the equivalent of s.376 is a

method which is alternative to any other method of service provided by the rules. at p.41

of the judgment.

77 See Part D of this article. In William Heinemann & Donald Moore v Christie (1960) 26

MLJ 99, a Federation of Malaya case, the defendant appeared to be registered as foreign

company but service was sought under the equivalent of O.10 r.2 instead.

78 See The Theodohos, supra note 30.

79 (1958) 24 MLJ 113, a decision of the High Court in Penang.

80 See s.387 of the Companies Act.

81 Supra, note 24. See also Chng Kim Huat v Hamburg Amerika-Nische [1936] MLJ Rep

216 where the court gave leave to amend a small irregularity in service.

82 See Nord Deutscher Lloyd v Ockerby and Co (1917) 14 WAR 104 where use of service

provision for locally incorporated company on a registered foreign company was not

permitted. The provisions discussed in this case are somewhat different from those found

in our Companies Act.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

119

Whilst the effect of irregularity of service under s.376 remains unclear, it

may be apposite to bear in mind that the objective of service, apart from

completing the process of obtaining jurisdiction, is to give the defendant

notice of proceedings. One wonders if slight transgressions which do not

affect the adequacy of notice might not be rectified without rendering the

proceedings a nullity.83

(ii) Cessation of Business in Singapore

If a registered foreign company ceases to carry on business, service may

still be effected through s.376. The English decisions on this point have

consistently decided that service is not affected by cessation of business. In

Employers Liability Assurance Corporation v Sedgwich and Collins, a

registered Russian company which was being liquidated but not yet dissolved

had ceased carrying on business within jurisdiction but did not remove the

name of the agent from the register. The majority of the House of Lords

held that the submission to jurisdiction continued notwithstanding the

cessation and as the agents name continued to remain in the register, the

company could be served through him. This decision was followed in

Sabatier where it was held in dictum that even if there was cessation of

business and abandonment of place of business which the Registrar was

informed, the retention of the agents name on the register was all that

mattered. Perhaps the most extreme case is Rome v Punjab National Bank

(No.2)84 where the same result was repeated despite cessation of business,

closure of the place of business, closure of the registers file on the company

on request for cancellation of registration and the withdrawal from

jurisdiction of its agents whose names, unfortunately for the company,

remained on the register. Punjab National Banks result is somewhat less

drastic when one considers that the court may exercise its discretion to

stay the action on forum non conveniens.

The policy rationale behind these cases is to prevent a foreign company

from uprooting itself with jurisdictional impunity (apart from being pursued

in its place of incorporation or through service out) leaving behind a trail

of local creditors.85 However, hardship may descend on a registered foreign

company which has long ceased to trade in the forum if it is sued on a

cause of action which has nothing to do with its local commercial

operations.86 Perhaps it was this concern which persuaded the High Court

of Australia in Gillett v National Benefit Life and Property Assurance Co

83 By analogy with some O.2 r.1 cases, such as The Goldean Mariner [1990] 2 Lloyds Rep

215. More serious irregularities or that which prejudice the defendant, of course, may

deserve less sympathy.

84 [1990] BCLC 20.

85 Rome v Punjab National Bank (No.2) [1989] 1 WLR 1211.

86 Punjab National Banks case, ibid, see the judgment of Parker LJ at p,1221.

120

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

Ltd87 to arrive at the opposite conclusion on facts roughly similar to Sabatier

and Punjab National Bank by reasoning that a company that ceases to

trade ceases to be present or resident within jurisdiction at the time of

service.

Given this dichotomy of decisions and policies, it is unclear which way

local courts88 might incline though the preponderance of authorities would

suggest that cessation of business is no immunity to jurisdiction. S.376(c)

is some indirect support for this position as well, as it allows service on a

foreign company at its place of incorporation when it has ceased to maintain

its place of business in Singapore.

Assuming no jurisdictional immunity, a registered foreign company that

ceases to maintain a place of business can still be served at its registered

office or at its agents registered address. If it has ceased to maintain the

place of business which it set up, then it can be served at its place of

incorporation in accordance with s.376(c). Since this involves service out,

it is unclear if leave of court is necessary.89 In addition, the agent of the

registered company which has quitted its place of business may also be

served under s.376(b).

In the light of the above decisions, a foreign company that wishes to cease

business or have a place of business would be well advised to give notice

to the Registrar of such cessation under s.377(1). The same provision states

that upon the expiration of 12 months after such notice, the companys

name would be removed from the register. Until then, service under s.376

seems still a looming possibility. Ex abundantia cautela, to avoid a situation

like Punjab National Bank where the companys file was closed but its

agents names remained, it should consider, for good measure, terminating

the authority of its agent as well and giving notice of such termination

under s.370(3).90 Again, if the company wishes to terminate an agents

authority to accept service without cessation of business, it has to give

notice under s.370(3) although s.370(5) obliges it to appoint another to

maintain the minimum requirement of at least two local agents.

87 Supra, note 26.

88 Certainly local authors take this position. See Woon and Hicks, The Companies Act of

Singapore: An Annotation in their annotation of s.376 at p. XI 121.

89 Woon and Hicks, ibid, think leave is unnecessary.

90 See also s.370(2) which states that an agent shall continue to be one until he ceases to

be such in accordance with subsection (4). It is unclear if this provision still continues to

apply if (i) the company has given notice under s.377 or (ii) upon removal of its name

from the register. There is an argument for saying that if the company has been removed

from the register, its agents, even if not having their authority terminated, should not be

left vulnerable to service when the very effect of registration has been reversed. Having

said there, Punjab National Bank, supra, note 85, is a disturbing reminder. Thus, removal

of agent under s.370(4) is a prudent move.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

121

(c) A Registered Company that subsequently neither carries on business

or establishes a place of business.

It can conceivably arise because the combined effect of ss.365 and 368 is

to require registration before either carrying on of business or establishment of place of business. Subsequently, such a company changes its mind

about commencing operations in Singapore. There is no direct authority

on whether such a company is amenable to jurisdiction and service under

s.376.

However, by analogy from the English cases on cessation of business

discussed above, it can be argued that as long as there is registration, s.376

service is possible. After all, there is little difference between not having

started business at all or have stopped business by the time service is

effected. However, if the justification for assuming jurisdiction over a

registered foreign company is that the latter has a corporate presence or

place of business in the forum, then it seems inconsistent that mere

registration alone, without any subsequent trading, should attract

jurisidiction.

(d) A company that ought to have registered but fails to do so.

This is the lacuna in s.376. S.376(a) and (b) are obviously inapplicable as

there would not be an address either of its registered office or its registered

agent since, to begin with, there is no registration. S.376(c) on its literal

wording may cover a narrow situation even for unregistered company but

when read with s.365, it is evident that it, as is the case with ss.376(a) and

376(b), only applies if the company is registered. This lacuna has recently

been implicitly been recognised by the Court of Appeal in Bank of Central

Asia v Rosenberg, in which Chao J compared s.376 with its English

counterpart, s.695(2)(a). The latter provision allows for service on any

place of business established by a company which defaults on registration.

Given the unavailability of s.376, service on, indeed the whole jurisdiction

basis applicable to such an unregistered company, falls outside the realm

of Part XI, Division 2 of the Companies Act. Other sources of jurisdiction

and other service provisions must be used for such a company. And it is

to this that attention is now turned.

D.

SERVICE IN SINGAPORE UNDER S.16(1)(a)(i) OF THE

SUPREME COURT JUDICATURE ACT

This provision, it will be recalled, confers jurisdiction upon the High Court

in action in personam where the defendant is served in Singapore in the

manner prescribed by the Rules of Court. It is submitted that for a

corporate defendant to be served in Singapore, there is a presupposition

that it is present in Singapore at the time of service in the sense of carrying

on business here for a definite period at a fairly permanent place of business.

122

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

In other words, the common law principle that a company must be present

before it can be served (which will be discussed shortly) is an implied

requirement of s.16(1)(a)(i).

This conclusion is best supported by reference to the Parliamentary debates

which ensued at the time the amendments to s.16 were mooted.91 The

Honourable Minister for Law in explaining the effects of the amendments

stated that:

Prior to 1964, the general civil jurisdiction of the High Court in

actions in personam was unlimited and founded on service of a writ

on a defendant either in Singapore or abroad...The amendment of

section 16 will place the High Court in exactly the position as it was

before 1964 and in the position of the High Court of Judicature in

England today in relation to countries outside the European Economic

Community.92

It is evident from the Ministers speech that the legislative intent behind

the 1993 amendments to s.16 is to re-introduce a jurisdictional framework

similar to that which exists at common law and based, in part, on service

on a defendant within jurisdiction. It follows that when it is invoked against

foreign corporate defendants, s.16(1)(a)(i) must therefore be interpreted

in the light of English common law principles which govern service on a

foreign company within jurisdiction. To put it in another way, the concept

of corporate presence must be read into expression in s.16(1)(a)(i),

... served... in Singapore...

A clarification is apposite at this juncture. Firstly, strictly speaking, insofar

as foreign corporate defendants are concerned, the current position in

England is not based on the common law, but rather on provisions of the

Companies Act 1985, as discussed above.93 But that, it is submitted, should

not affect the position of unregistered foreign companies, the service on

which is not covered by s.376 of our Companies Act. This local lacuna was

also prevalent in England prior to the introduction of s.349 of the English

Companies Act 1929 (the equivalent of s.695(2) of the present Act) to deal

with service on unregistered foreign companies. English courts responded

to this lacuna, and indeed, prior to the introduction of legislation on this

area in 1907,94 to the whole problem of jurisdiction over foreign companies,

by the enunciation of common law principles on corporate presence. There

is no reason why such common law principles cannot be garnered to fill up,

91 Reference to Parliamentary debates is permissible in the interpretation of statutes. Supra,

note 44.

92 Parliamentary Debates Singapore, Official Report, Volume 61, No 1 at col 95.

93 See The Theodohos, supra, note 30, as well as the Dicey and Morris, Conflict of Laws

and Cheshire and North, Private International Law at p. 185186.

94 Supra, note 32 for an account of the English legislative history on the area.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

123

through another statutory channel,95 the lacuna in our s.376 just because

the problem has been eradicated in England since 1929.

(a) Presence of a Foreign Company at Common Law

Although it has been decided as far back as 1872,96 that a foreign company

can be sued in England, the use of terminology in the caselaw has not been

uniform. Presence of a foreign company within jurisdiction of the forum

has variously been described as having a residence within jurisdiction,97 a

place of business within jurisdiction,98 a domicile within jurisdiction99 or

carrying on business within jurisdiction100 or simply being here within

jurisdiction.101 For ease of exposition, the term, corporate presence which

is favoured by some writers,102 is used throughout this article.

The concept of corporate presence is analogous to presence of the individual

within the territory of the Sovereign which subjects him to the jurisdiction

of the courts in that country. As a company cannot be physically present

like an individual, it can only be present through the business it carries on

within the territory of the country in which the action is brought. Thus, as

is the case with individuals, it is the companys territorial connection with

the forum that matters. The relevant time for assessing corporate presence

is the time of service of process, so that if at that time, a company has

ceased trading, it cannot be served within jurisdiction.103

There are two requirements for corporate presence.104 First, the company

that conducts business within jurisdiction by means of an agent who has

authority to enter transactions on its behalf would be considered to be

present for jurisdictional purposes. A company may instead of being

represented by an independent agent have a branch office staffed by its

95 Viz s.16(1)(a)(i), SCJA.

96 Newby v Van Oppen (1872) LR 7 QB 293. For a detailed account of cases on this area

at the turn of the century, see Farnsworth, The Residence and Domicil of Corporations

(1939).

97 See for instance, La Bourgogne, supra, note 50 (CA decision); Newby v Van Oppen, ibid,

Haggin v Comptoir DEscompte de Paris (1889) 23 QBD 519.

98 Huron & Eries case, supra, note 48.

99 See for instance, the decision of Canon Iron v Mclaren 5 HLC 416

100 See for instance, the decision of Lhoneux Limon and Co v Hong Kong and Shanghai

Bank (1886) 33 Ch D 446.

101 Newbys case, supra, note 96.

102 See for instance, Cheshire and North, supra, note 28, at p. 185.

103 Adam v Cape Industries, supra, note 52. Also the Singapore decision of Korea Metals

Export Corporation v Sakota Ltd SA [1973] 1 MLJ 228 where service was invalidly

effected on the defendants former agent which had ceased to carry on business. See also

Bethlehem Steel Corporation v Universal Gas and Oil Co Inc (a House of Lords decision,

The Times, 3rd August 1978) where a mysterious company which neither carried on

business or had a place of business in England successfully avoided service. This case is

an example of a foreign company operating in a phantasmic manner and managing to

evade a fairly extensive jurisdictional net.

104 These requirements were most clearly laid down in Okura & Cos supra, note 51 though

they have been alluded to in the earlier cases as well.

124

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

own employees in the forum which carries on its business.105 The same

requirements apply to both forms of representation but in the case of

independent agent, the question of authority to contract on the companys

behalf must be more closely examined. Being represented by an agent per

se is not sufficient. It must be shown that the business the agent conducts

must be the companys and not his own.106 So long as it is the companys

business that is carried on within jurisdiction, it does not matter if such

business is the paramount object of the company or merely incidental to

that. Thus, in Actiesselskabet Dampskib Hercules v Grand Trunk Pacific

Railway,107 the defendants business in England was solely the raising of

finances to run a railway in Canada; it was still held to be present in

England. The carrying of the foreign principals business is effected by the

making of contracts on the latters behalf, though such an agent may also

act for other parties.108 If a company is represented by an agent who only

receives orders and transmits them abroad to his foreign principal for

acceptance, then the company is not carrying on business within

jurisdiction109 , for it is then regarded as doing business through the agent,

not by him.110 Equally, an agent which carries out its own business by

selling contracts with the foreign company would not render the latter

present within jurisdiction.111

Authority to contract on the foreign companys behalf, although a principal

aspect in the relationship between the agent and its foreign principal to

consider, is not the only one. Slade LJ in Adams v Cape Industries listed

105 Adams v Cape Industries, supra, note 52 recognises that a foreign company can be present

through an independent agent or a branch office. The requirements in Okuras case

apply to both forms of representation, albeit that in that case of an independent agent,

the question of authority to contract for the company has to be more closely examined.

Adams v Cape Industries, supra, note 52, is actually a decision on enforcement of foreign

judgment but the court there assumed that cases on jurisdiction and foreign judgments

can be used interchangably. For an Australian perspective, see National Commercial

Bank v Wimborne, (1979) 11 NSWLR 156, a decision of the Supreme Court of New

South Wales which essentially adopts the English principles.

106 See Thames & Mersey Marine Insurance v Societa Lloyd Austriaco (1914) 111 LT 97.

107 [1912] 1 KB 222. Cf. Some Canadian cases take a different stance: the business done by

the agent must be an integral part of the business of the foreign company and not merely

incidental to it. See, for instance, Canada Life Assurance v Canadian Imperial Bank

[1974] 3 OR (2d) 70 and Central Trust of China v Dolphin SS Co Ltd [1950] 2 WWR 516.

108 Saccharin Corporation Limiteds case, supra, note 64.

109 See, for instance, Okuras case, supra, note 51; Vogel v Kohnstamm, supra, note 38 (a

decision on enforcement of foreign enforcement); Grant v Anderson [1892] 1 QB 108.

110 Buckley LJ in Okuras case, supra, note 51. This point is similar to the agent having

authority to contract on his principals behalf: see the Court of Appeal decision in Bank

of Central Asia v Rosenberg, supra, note 19.

111 See The Lalandia [1933] P 56; Thames and Mersey Marine Insurance, supra, note 106.

These cases involve shipping agents which sold passenger tickets or shipping space to

third parties. See also The Holstein [1936] 2 All ER 1660.

7 S.Ac.L.J.

Obtaining Jurisdiction Over Foreign Companies

125

some other relevant factors, such as the method of remuneration of the

agent,112 the degree of control the foreign company has over the running

of the agents business, whether the foreign company defrays for the cost

of running the agents business, in the form of payment of salary and

rental, the degree of publicity the agency relationship is given by and how

much of the agents premises and manpower are allocated to carrying on

the principal business. While it is wrong to say that there can never be

corporate presence if authority to contract on the principals behalf is

wanting, the circumstances pointing towards corporate presence in such a

situation would have to be very compelling.

The second requirement is that the foreign company must have operated

its business (whether through an independent agent or a branch office) for

more than a minimal period of time at a fixed place of business. A foreign

company need not be the owner or lessee of the premises where it has its

place of business, though either form of tenure would be a cogent piece of

evidence against them. Thus, corporate presence is not defeated by the

foreign company being a mere licensee, or that the premises house other

parties business. So in Saccharin Corporation Limited v Chemische Fabrik

vonHeyden, 11 3 a company was held to have a place of business in premises

the rental for which was paid by its agent who also conducted other parties

business in the same place. As Fletcher Moulton LJ observed in the case,

it is the fixity of the place of the business that matters, not the tenure by

which such fixity is arrived. However, as Dunlop Pneumatic v AG Cudell11 4

illustrates, even an exhibition booth which the defendant occupied for nine

days has been held to satisfy this requirement. However, where a company

only employs commercial travellers who come within jurisdiction to place

orders or solicit business without being at any definite or permanent place,

as was what happened in Littauer Glove Corporation v Millington Limited,115

it cannot be said to have established a place of business. As for the length

of time business must be carried out at the time of business, the courts

have not been very exacting and on one occasion, as mentioned above,

held that nine days were sufficient though one isolated transaction in a

long while may be insufficient to constitute corporate presence.116 That the

place of business is seen to be associated with the company is another

important indicium. Thus, there has been judicial scrutiny of the ways of

publicising the companys presence at a particular location, such as display

112 On this point, see cases such as Saccharin Corporation, supra, note 64; The Lalandia,

supra, Grant v Anderson supra and Thames & Mersey, supra, note 111. This factor was

something the courts in these cases considered but did not seem have a decisive influence

on the outcome.

113 Supra, note 64.

114 Dunlop Pneumatic Cos case, supra, note 49.

115 (1928) 44 TLR 746, a decision of enforcement of foreign judgment.

116 Colley v Mead, supra note 67; Lamson v Weidenbach, supra, note 67.

126

Singapore Academy of Law Journal

(1995)

of the foreign companys name in the agent or branch offices premise or